Jeffrey Sachs

SOMERVILLE, Mass.

It is hard to feel much sympathy for Jack Teixeira, the Air National Guardsman from North Dighton, Mass., who is accused of sharing top-secret U.S. government documents with his obscure online gaming group. It was from there that, predictably, the secrets gradually slipped out into the larger world. Still, the news story that caught my attention was one in which a friend from the original game-group explained to a Washington Post reporter what he understood to have been the 21-year-old guardsman’s motivation.

The friend recalled that Teixeira started sharing classified documents on the Discord server around February 2022, at the beginning of the war in Ukraine, which he saw as a “depressing” battle between “two countries that should have more in common than keeping them apart.” Sharing the classified documents was meant “to educate people who he thought were his friends and could be trusted” free from the propaganda swirling outside, the friend said. The men and boys on the server agreed never to share the documents outside the server, since they might harm U.S. interests.

The opinion of a callow 21-year-old scarcely matters, at least on the surface of it. Discussions will quickly shift to the significance of the leaked information itself. Comparisons will be made of Teixeira’s standing as a witness to government policy, and judge of it, relative to others of similar ilk: Daniel Ellsberg, Chelsea Manning, Edward Snowden, Julian Assange, and Reality Winner.

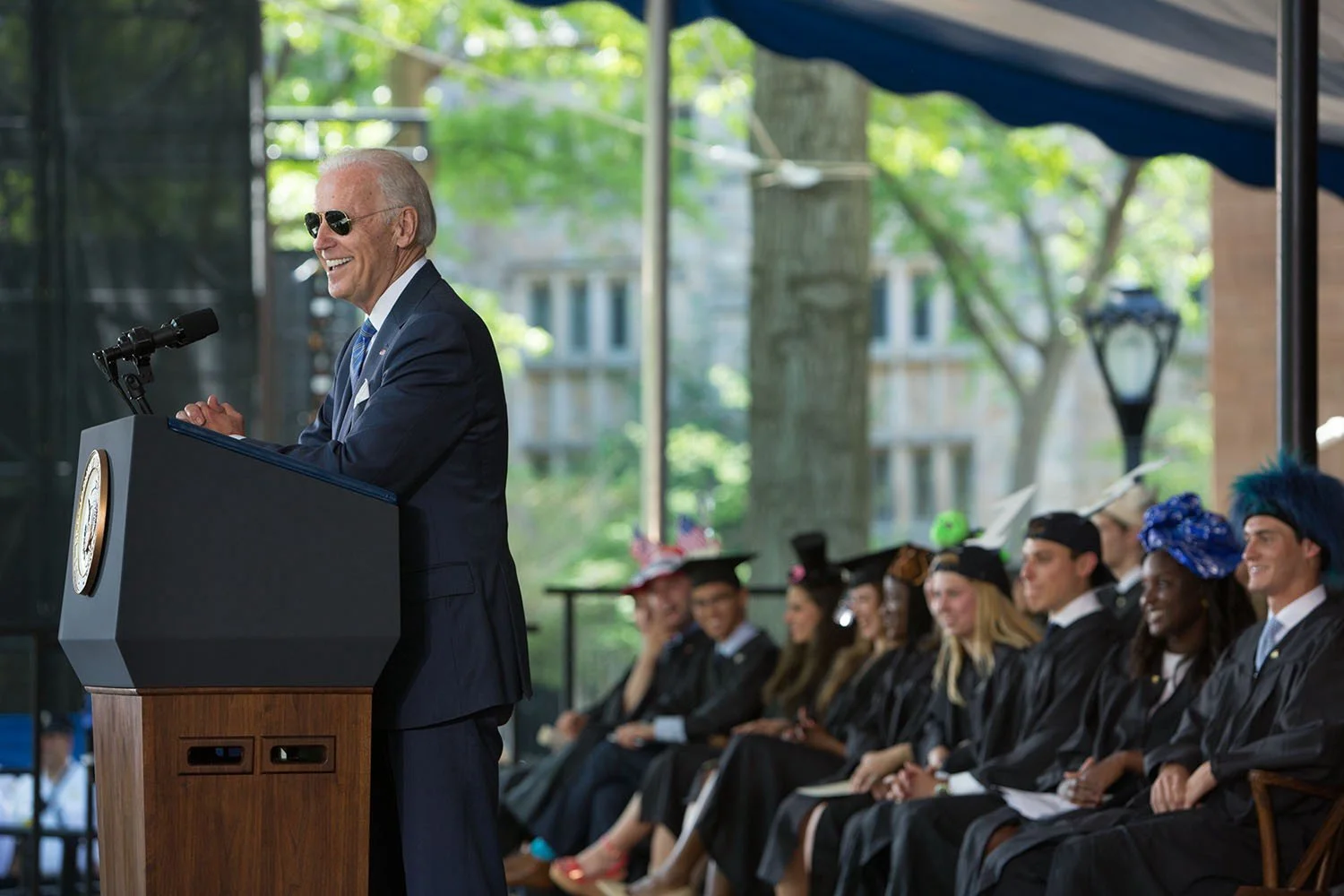

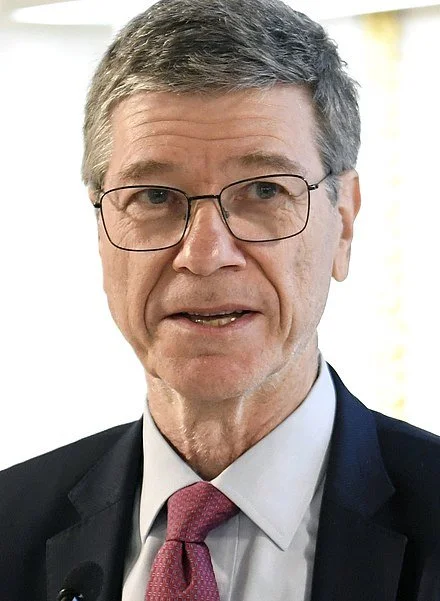

But Teixeira’s opinion interested me mainly because it mirrored views increasingly under discussion at all levels of American civil society. I thought immediately, for instance, of Jeffrey Sachs, director of the Center for Sustainable Development at Columbia University. Sachs is not widely understood to be involved in the story of the war in Ukraine. But since 2020, and the death of Stephen F. Cohen, of New York University, Sachs has become the leading university-based critic of America’s role in fomenting the war.

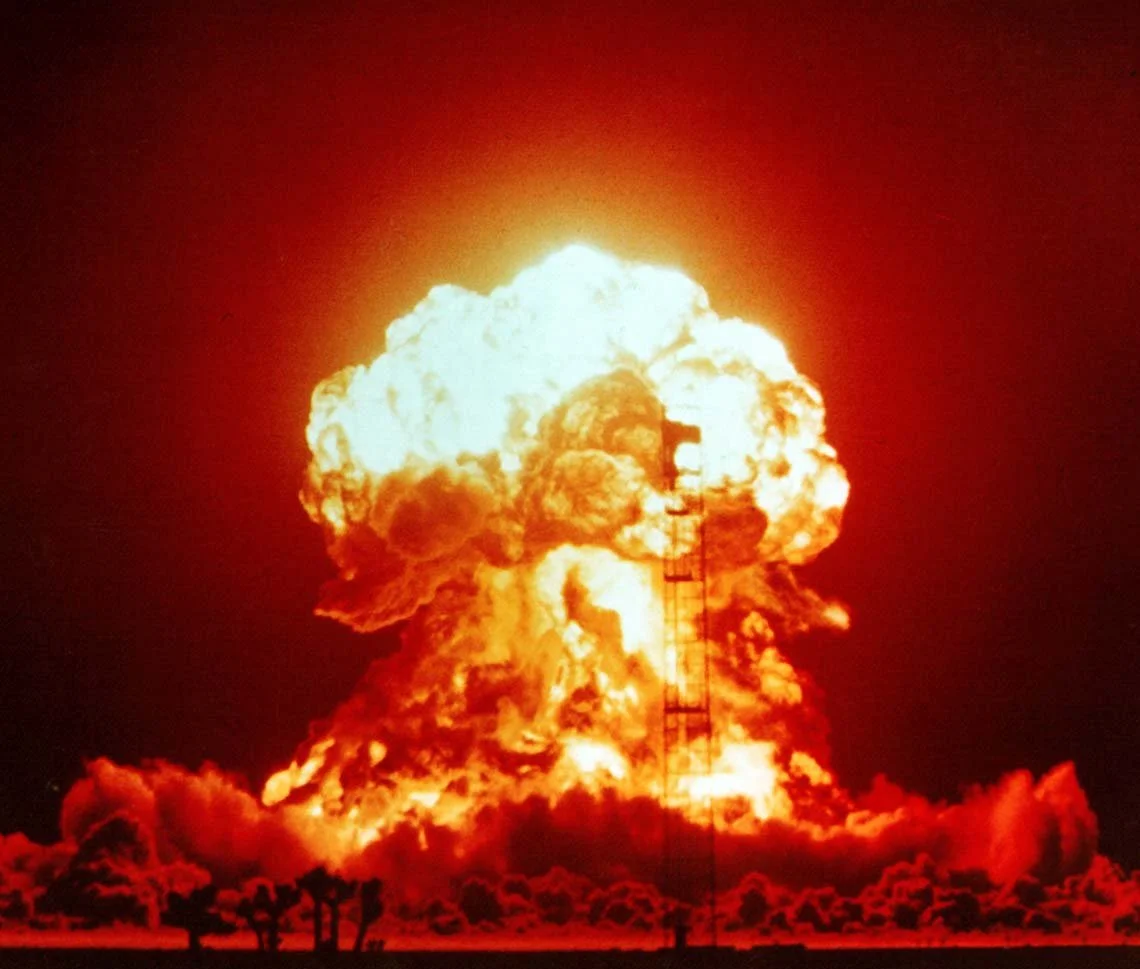

On Feb. 21, Sachs appeared before a United Nations session to present a review of the mysteries surrounding the destruction of Russia’s nearly complete Nord Stream 2 pipeline last September. The consequences were “enormous,” he said, before calling attention to an account by independent journalist Seymour Hersh that ascribed the sabotage to a secret American mission authorized by President Biden.

Despite a history of previous investigative-reporting successes (My Lai massacre, Watergate details, Abu Graib prison), Hersh’s somewhat hazily sourced story was not taken up by leading American dailies. In an apparent response to the attention given to Sachs’s endorsement of it, however, national-security sources in Washington and Berlin soon surfaced stories of their investigation of a mysterious yacht, charted from a Polish port, possibly by Ukrainian nationals, that might have carried out the difficult mission. Hersh responded forcefully to the “ghost ship” stories in due course.

Then on Feb. 28, at a time when English-language newspapers were writing about the year since Russia had boldly launched an all-out invasion of Ukraine, Sachs published on his Web site his own version of the story. “The Ninth Anniversary of the Ukraine War’’ is a concise account of Ukrainian politics since 2010. Especially interesting is Sachs’s analysis of U.S. involvement:

During his presidency {of Ukraine} (2010-2014), {Viktor} Yanukovych sought military neutrality, precisely to avoid a civil war or proxy war in Ukraine. This was a very wise and prudent choice for Ukraine, but it stood in the way of the U.S. neoconservative obsession with NATO enlargement. When protests broke out against Yanukovych at the end of 2013 upon the delay of the signing of an accession roadmap with the EU, the United States took the opportunity to escalate the protests into a coup, which culminated in Yanukovych’s overthrow in February 2014.

The US meddled relentlessly and covertly in the protests, urging them onward even as right-wing Ukrainian nationalist paramilitaries entered the scene. US NGOs spent vast sums to finance the protests and the eventual overthrow. This NGO financing has never come to light.

Three people intimately involved in the US effort to overthrow Yanukovych were Victoria Nuland, then the Assistant Secretary of State, now Under-Secretary of State; Jake Sullivan, then the security advisor to VP Joe Biden, and now the US National Security Advisor to President Biden; and VP Biden, now President. Nuland was famously caught on the phone with the US Ambassador to Ukraine, Geoffrey Pyatt, planning the next government in Ukraine, and without allowing any second thoughts by the Europeans (“Fuck the EU,” in Nuland’s crude phrase caught on tape).

So, who is Jeffrey Sachs, anyway, and what does he know? It’s a long story. His Wikipedia entry tell you some of it. What follows is a part of the story Wiki leaves out.

Sachs was born in 1954. Having grown up in Michigan, the son of a labor lawyer and a full-time mother, he graduated from Harvard College in 1976. As a Harvard graduate student, he soon found a rival in Lawrence Summers, the nephew of two Nobel-laureate economists, who had graduated the year before from Massachusetts Institute of Technology.

Sachs completed his PhD in three years, after being appointed a Junior Fellow, 1978-81. Harvard Prof. Martin Feldstein supervised his dissertation, and, three years later, supervised Summers as well. Both were appointed full professors in 1983, at 28, among the youngest ever to achieve that position at Harvard. Sachs collaborated with economic historian Barry Eichengreen on a famous study of the gold standard and exchange rates during the Great Depression. Summers was elected a Fellow of the Econometric Society in 1985, Sachs the following year.

Summers went to Washington in 1982, to serve for a year in the Council of Economic Advisers under CEA chairman Feldstein; in 1985, Sachs was invite to advise the government of Bolivia on its stabilization program. After success there, he was hired by the government of Poland to do the same thing: he was generally considered to have succeeded. In 1988, Summers advised Michael Dukakis’s presidential campaign; in 1992, he joined Bill Clinton’s presidential campaign. Sachs became director of the Harvard Institute for International Development.

In the early 1990s, Sachs was invited by Boris Yeltsin to advise the government of the soon-to-be-former Soviet Union on its transition to market economy. Here the details are hazy. Clinton was elected in November 1992. During the transfer of power, another young Harvard professor, Andrei Shleifer, was appointed to run a USAID contract awarded to Harvard to formally offer advice, thus elbowing aside Sachs, his titular boss. Shleifer had been born in the Soviet Union, in 1962; arriving with his scientist parents in the US in 1977. As a Harvard sophomore, he met Summers first in 1980, becoming Summers’ protégé, and, later, his best friend.

In 1997, USAID suspended Harvard’s contract, alleging that Shleifer, two of his deputies, and his bond-trader wife, Nancy Zimmerman, had abused their official positions to seek private gain. Specifically, they had become the first to receive a license from their Russian counterparts to enter the Russian mutual fund business, at a critical moment, as Yeltsin campaign for election to a second term. A week later Sachs fired Shleifer, and the project collapsed. Stories in The Wall Street Journal played a key role. And two years later, the U.S. Department of Justice file suit against Harvard and Shleifer, seeking treble damages for breach of contract. All this is describe in Because They Could: The Harvard Russia Scandal (and NATO Enlargement) after Twenty-Five Years, a book I dashed off after 2016 as I was turning my hand from one project to another.

Soon after the government file its suit, George W. Bush defeated Al Gore in the “hanging chad” election of 2000, and a few months after that, Harvard hired former Treasury Secretary Larry Summers as its president. Harvard lost is case in 2004 in 2005, and Summers’s defense under oath of Schleifer’s conduct played a role – who knows how great? – in Summers’s overdetermined decision to resign his presidency in 2006. By then, Sachs had long since decided to leave Harvard. In 2002, after 25 years in Cambridge, he became director of Columbia University’s newly established Earth Institute, uprooting the pediatric practice of his physician wife as part of the move.

Sachs was always reluctant to talk about Harvard’s Russia caper. I haven’t spoken to him in 27 years. At Columbia, he enjoyed four-star rank, both in Manhattan, and in much of the rest of the world, serving for 16 years as a special adviser to the UN’s Secretary General, beginning with Kofi Annan. Time put his book, The End of Poverty,: Economic Possibilities for Our Time, on its cover; Vanity Fair’s Nina Munk published The Idealist: Jeffrey Sachs and the Quest to End Poverty, in 2013; glowing blurbs, from Harvard’s University’s Dani Rodrik and Amartya Sen, attested to his standing in the meliorist wing of the profession. In 2020, Sachs became involved, with a virologist colleague, in the COVID “lab-link” controversy, first on one side, then on the other. His stance on the Ukraine war had earned him plenty of criticism.

Sachs will turn 70 next year. He stepped down from the Earth Institute in 2016. As a university professor at Columbia, he teaches whatever he pleases. He writes mainly on his own web page, where he is always worth reading. But he is spread too thin there to influence more than occasionally the on-going newspaper story of the war. As a life-long dopplegänger to Larry Summers, however, Sachs casts a very long shadow indeed.

David Warsh, a veteran columnist and an economic historian, is proprietor of Somerville-based economicprincipals.com, where this column first ran.