Shakespeare & Company’s campus, in Lenox, Mass. The organization is a theater company and venue complex founded in 1978. Shakespeare took innumerable liberties with the historical record.

WEST WARWICK, R.I.

The trouble with history is that no one can agree on what happened. That is how historians can wrangle over events 2,000 years ago — or two months ago.

Prominent historians become more famous when they feud with other prominent historians. One such feud, which became very public, was between the British historians Hugh Trevor-Roper and A.J.P. Taylor over the origins of World War II. They went at it as only academics can.

The trouble worsens when fiction enters; and fiction always enters and distorts. Fiction doesn’t let the facts stand in the way of a good story. The Greeks did it with Homer, and it has gone on ever since.

But the greatest muddier of history was William Shakespeare, whether it was the demonization of Richard III and the two young princes in the tower, or whether Marc Antony was a great orator or whether Cleopatra was a gorgeous seductress. Mostly, what we think we know about these historical figures, we got from Shakespeare or some other creative writer.

The playwright George Bernard Shaw couldn’t leave Cleopatra or alone either. He also had a go at Joan of Arc and muddied the history there, not that it has ever been clear — history never is.

Historical fiction is historical distortion by definition, which gets steroidal when movies are involved.

Two recent movies are opposed in the degree of historical truthfulness the directors, both British, have cared about. Christopher Nolan gave us Oppenheimer, which is extraordinary in its fidelity to the facts, and even mood. Oppenheimer captures the ethos of a congressional hearing exactly.

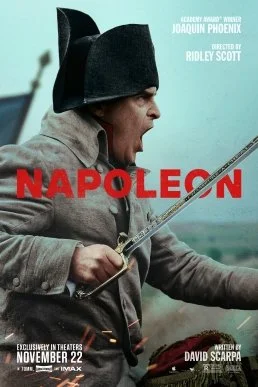

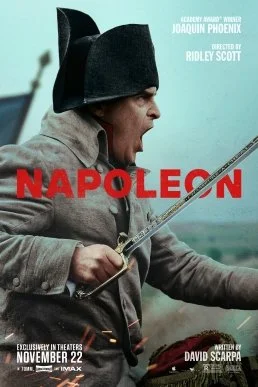

Ridley Scott has made Napoleon without interest in Napoleon besides a sort of comic-book acquaintance with his subject.

He was, it would seem, more interested in what happens when a cannon takes out a horse, than facts about the niceties of the little Corsican’s extraordinary career. Also, he has based much of the story line on Napoleon’s relationship with Josephine, little on his administrative ability, which was the underpinning of his military success, and made modern France.

Napoleon makes life difficult for filmmakers because he was a romantic figure, even in Britain, when he was at war with the British. Witness how his affair with Josephine has taken on legendary proportions as one of history’s great love affairs. Or his defeat at Waterloo.

There is a puzzler: Waterloo was a great victory for Britain and its allies, but in idiomatic English, Waterloo has become a metaphor for defeat. A belated victory for Napoleon, you might say.

Then there is the general’s name. Why does history call Napoleon Bonaparte by his first name? The Duke of Wellington’s “real” name was Arthur Wellesley. And does anyone know or care that he was Tory prime minister twice or that he was from Ireland?

No, Bonaparte carries off the honors and continues to win the information war long after his death.

The two inaccuracies which bother historians most about Scott’s film are that Napoleon didn’t witness the guillotining of Marie Antoinette and French didn’t launch artillery at the pyramids, nor did they blast the nose off the Sphinx.

Another challenge is historical fiction on television — much of it produced by the BBC.

The BBC has an edict that casting must reflect the current multiracial face of Britain. This results in black and Asian courtiers and noblemen romping around England in the time of Henry VIII. So long as the story and the acting keeps to the high standard, which has been established by BBC drama, I don’t mind. It is just actors and many of them are excellent. However, what will young people, who don’t learn much history these days, make of this?

We don’t expect that something similar would happen in Japanese TV drama, like English noble ladies and gents romping around the divine emperor’s medieval court; nor would we expect to see Hollywood’s finest cavorting in China’s Forbidden City.

It intrigues me that history can become so malleable in the writers’ and filmmakers’ hands. Scott is said to have dismissed one critic on the grounds that he wasn’t there, and he wasn’t entitled to comment.

While many, like Scott, believe that it is okay to mess with the facts, another set of historical vandals has passed judgment on the past and wants to punish heroes of yesteryear for what they did as judged by today’s standards. Those revisionists are busy tearing down statues and trashing all kinds of figures in an effort to serve posthumous justice.

Bringing down the marble or bronze is a current obsession with what passes as history, whether we get it right or not.

Llewellyn King is executive producer and host of White House Chronicle, on PBS. His email is llewellynking1@gmail.com, and he’s based in Rhode Island and Washington, D.C.