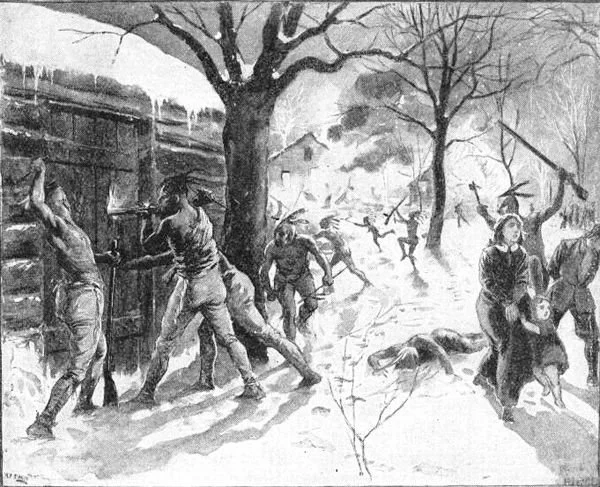

These Spanish Colonial era buildings are a common sight across Havana, along with old cars.

— Photo by Bryan Ledgar

There was much business done in Cuba by New England enterprises, especially in sugar but also in tobacco and fruit. Here’s the Soledad plantation of Belmont, Mass.-based sugar mogul Edward F. Atkins. In the late 19th Century, Atkins was a dominant force in the U.S.-Cuban sugar market. His firm, E. Atkins & Co., established sugarcane plantations along the southern coast of Cuba near the cities of Cienfuegos and Trinidad. From the 1840s through the 1920s, the Atkins family operated their sugar business on the island, seeing it through the abolition of slavery, Cuba's fight for independence from Spain, and the changing agricultural and industrial practices of sugar production.

The huge and Boston-based United Fruit Co. owned or leased many properties in Cuba.

I have had a hankering to go back to Cuba. I went there with other journalists on a trip organized by the Center for Strategic and International Studies in the 1980s; and again on a National Press Club trip in 2003.

Over Christmas I went back, just to Havana, that dowager city, and lost myself in the best of Cuba: its architecture, its food, its music and its people.

But around me were plenty of signs of the other Cuba, the Cuba which is in extremis — the Cuba which is driving its citizens to leave in record numbers.

In 2022, by some accounts, about 400,000 Cubans left for work and a new life wherever in the world they could find it. The Customs and Border Protection agency estimates that in a recent two-year period, 425,000 sought entry to the United States.

Many Americans are surprised to hear that you can travel easily to Cuba these days. The confusion arises as the law seems to say “no,” but the regulations posted by the Treasury Department say “yes.”

My wife and I went through a commercial Cuba travel service called Cuba Explorer. We didn’t want to go as journalists; we wanted to take a quiet look at Havana, not through the eyes of officialdom. We signed up and so did two friends, a retired doctor and his wife.

The tour company arranged our Cuban visa and the “Certificate of Legal Cuba Travel,” a U.S. requirement. All we did was buy our tickets on American Airlines, which operates daily service from Miami. Delta, Southwest and JetBlue and also fly to Havana from various cities.

Border formalities are no more difficult than they are going to any country — say, Mexico or the United Kingdom.

Havana — and some of the smaller colonial towns which I visited previously — is a delight. It is among the great “built cities” of the world, like Paris, Vienna and St. Petersburg. However, as Havana is compact, it is easily seen; it is the kind of place you feel you can get your arms around.

The grandeur of its colonial past, its wealth of another time, is everywhere. So is the poverty of today. Some streets are sad, indeed, with all the manifestations of poor countries: people picking over garbage, pedal carts, even bullock carts. There are few overweight people and while Cuban food is complex and sophisticated, I’m told that Cubans survive on rice and beans.

Cubans also queue. Jokingly, one Cuban told me, “When we see a line, we go and stand in it — must be something good and, like all good things here, in short supply.”

Food for those outside the dollar-driven tourist economy is a struggle, as are medicines and simple things, like a favorite shampoo or paper products of all kinds. For travelers, one of the pleasures of Havana is that you always get a cloth napkin, not of choice but of necessity. Our new, comfortable hotel ran out of toilet paper. The American obsession with carrying Kleenex came in handy.

The 1950s cars are as plentiful as ever, but many are reengineered with modern Japanese or Russian engines; some declare they are all original parts and use Cubans abroad to scavenge junk yards and send parts back in relatives’ luggage.

The sanctions, with small modifications, have lasted since 1962, and are the longest-ever in U.S. history — and they haven’t worked. They haven’t brought down the Communist Party, freed the press or made the life of Cubans any better. Instead, they have subtracted hope.

The embargo is a peculiar cross that Cuba alone bears, especially when you think of the many dictatorial regimes we tolerate and befriend.

The Hill reported that Mexican President Andres Manuel Lopez Obrador told President Biden in a phone call that he could help reduce migration in the region if he could loosen the sanctions on Cuba. It is hard to find a Cuban who wants to leave the island, but wouldn’t if he or she could.

After 20 years, I had hoped to find a more prosperous Cuba, but it hasn’t happened. The small areas of free enterprise allowed by the state have created little oligarchies. Taxi drivers and waiters make much more money than doctors and engineers. These professionals count among Cuba’s exports, its brain drain. On the upside, there are many private restaurants with a thriving food culture for those who can afford it.

The fault is the failed Cuban communist model, but the United States hasn’t helped. Graham Greene, the great British writer, who penned The Power and the Glory, about the Mexican Revolution — from 1910 to 1920 —pointed out that it failed without the aid of an American embargo.

I have felt, now for 40 years, that Cuba would throw off communism if we let it alone, and got rid of the embargo, which is more about U.S. politics than the politics of Cuba.

Meanwhile, do visit Cuba while you can. It is a treat for the eyes, the ears and the palate. You won’t regret it.

Llewellyn King is executive producer and host of White House Chronicle, on PBS. His email is llewellynking1@gmail.com, and he’s based in Rhode Island and Washington, D.C.