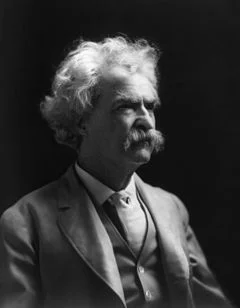

— Mark Twain (1835-1910), a long-time resident of Connecticut

Who makes this stuff?

The June 1, 2011 tornado that killed three people in and around Springfield, Mass.

— Photo by Runningonbrains

“I reverently believe that the Maker who made us all makes everything in New England but the weather. I don’t know who makes that, but I think it must be raw apprentices in the weather clerk’s factory who experiment and learn how, in New England, for board and clothes, and then are promoted to make weather for countries that require a good article, and will take their custom elsewhere if they don’t get it….’’

–Mark Twain (1835-1910)

If you’re not partly a coward you’re not brave

— Photo by Makemake

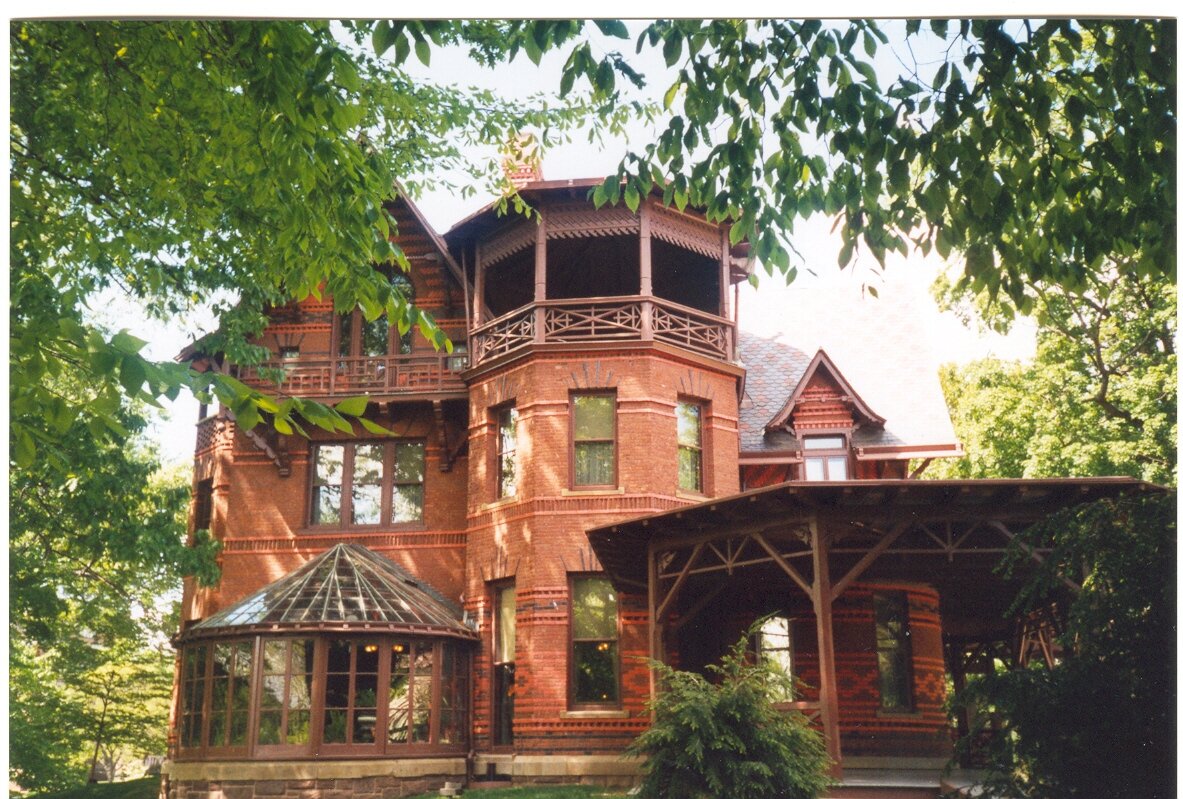

The Mark Twain House, now a museum, in Hartford, Conn., where he lived in 1874-1891. He then lived abroad and in New York City before spending his last years in Redding, Conn., in the grand house below, which burned down in 1923.

“Courage is resistance to fear, mastery of fear-not absence of fear. Except a creature be part coward it is not a compliment to say it is brave; it is merely a loose misapplication of the word. Consider the flea! - -Incomparably the bravest of all the creatures of God, if ignorance of fear were courage. Whether you are asleep or awake he will attack you, caring nothing for the fact that in bulk and strength you are to him as are the massed armies of the earth to a sucking child; he lives both day and night and all days and nights in the very lap of peril and the immediate presence of death, and yet is no more afraid than is the man who walks the streets of a city that was threatened by an earthquake ten centuries before. When we speak of Clive, Nelson, and Putnam as men who ‘didn't know what fear was,’ we ought always to add the flea-and put him at the head of the procession.”

— Mark Twain, in Pudd’nhead Wilson (1893)

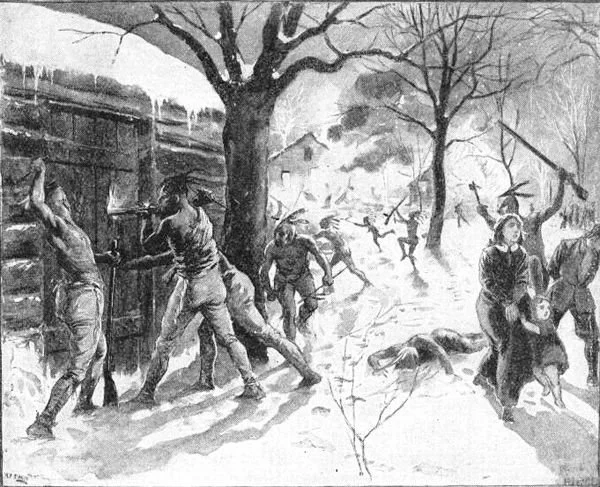

Forget poems about spring here

“The people of New England are by nature patient and forbearing, but there are some things which they will not stand. Every year they kill a lot of poets for writing about ‘Beautiful Spring.’ These are generally casual visitors, who bring their notions of spring from somewhere else, and cannot, of course, know how the natives feel about spring. And so the first thing they know the opportunity to inquire how they feel has permanently gone by.’’

— Mark Twain, in a speech at a New England Society dinner on Dec. 22, 1876

Don Pesci: 'A moralist in disguise,' Mark Twain was funny and deadly serious on politics

Mark Twain photographed in 1908 via the Autochrome Lumiere process.

Anyone hoping to hammer into a coherent ideology Mark Twain’s robustly critical admonitions on politics and politicians is bound to be disappointed. (Reminder to New Englanders: Twain lived for many years in Hartford.)

Here is Twain on the Congress of his day: “An honest man in politics shines more there than he would elsewhere.” That is taken from A Tramp Abroad, written in Hartford, Connecticut. Twain wrote most of his important novels in Hartford, including The Adventures of Tom Sawyer, The Prince and the Pauper, Life on the Mississippi, Adventures of Huckleberry Finn and A Connecticut Yankee in King Arthur's Court. Towards the end of his life, tragedy became the uninvited guest at Twain’s table. He lost his beloved wife, both a spiritual anchor and a literary censor. Twain did not believe that writers should self-censor. Olivia Clemons was concerned about her husband’s place in the world, as all good wives should be, and worked to keep his combustible politics from bursting into flame – at least publicly -- and singeing the politicians of his day and ours.

The following dictation note is taken from the Autobiography of Mark Twain: “Look at the tyranny of party -- at what is called party allegiance, party loyalty -- a snare invented by designing men for selfish purposes -- and which turns voters into chattels, slaves, rabbits, and all the while their masters, and they themselves are shouting rubbish about liberty, independence, freedom of opinion, freedom of speech, honestly unconscious of the fantastic contradiction; and forgetting or ignoring that their fathers and the churches shouted the same blasphemies a generation earlier when they were closing their doors against the hunted slave, beating his handful of humane defenders with Bible texts and billies, and pocketing the insults and licking the shoes of his Southern master.”

Twain left instructions that his uncensored autobiography, a product of his political “pen dipped in Hell,” should not be let loose on the general public until a century had passed after his death.

This from A letter to Helene Picard, in 1902: “Yes, you are right -- I am a moralist in disguise; it gets me into heaps of trouble when I go thrashing around in political questions.” Helen Picard was the French member of Twain’s private “Juggernaut Club.”

Here is Twain’s note to Helen, published in the Lady’s Home Journal posthumously, as was much of his writing on politics: “I have a Club, a private Club, which is all my own. I appoint the Members myself, and they can't help themselves, because I don't allow them to vote on their own appointment and I don't allow them to resign! They are all friends whom I have never seen (save one), but who have written friendly letters to me. By the laws of my Club there can be only one Member in each country, and there can be no male Member but myself. Someday I may admit males, but I don't know -- they are capricious and inharmonious, and their ways provoke me a good deal. It is a matter which the Club shall decide.”

Seriously?

Twain died on April 21, 1910 of a heart attack in Redding, Conn., where he had moved to escape certain ghosts. Perhaps not unexpectedly, the death of those he most loved liberated him. Following his near bankruptcy, the premature death of his daughter Susy of spinal meningitis at age 24 in 1896 and the passing of his wife, Olivia, in 1904, Twain went “thrashing around in political questions.”

Was Twain serious in his political writings? Indeed, is it possible to take seriously any humorist? He was deadly serious, and his writings did get him into no end of trouble with his political targets, among them President Theodore Roosevelt. Twain thought Roosevelt a rare political showman and a preposterous fraud. Roosevelt, for his part, wanted to strangle Twain – and said so.

But the question is an important and serious one: can someone with a comic turn of mind say anything useful about politics in the widest sense of the word? For a broad thinker like Aristotle, politics was anything and everything having to do with the polis, the nation state of his day. The family, for instance, was, in Aristotle’s view, a primary political unit. What we know of Socrates we have gleaned from two sources: Plato, whom everyone takes seriously, and Aristophanes, the most famous Greek comic playwright of his day and a contemporary of Socrates.\

One day, someone, possibly a political flunky whose patron Aristophanes had raked over the coals in one of his nuclear tipped theatrical satires, approached him in the street and demanded to know, “Don’t you take anything seriously?” to which Aristophanes replied, “Of course, I take comedy seriously.” Very Twainian that response.

Was Twain serious when he said of Teddy Roosevelt in a letter to Joseph Twichel in 1905, “We are insane, each in our own way, and with insanity goes irresponsibility. Theodore the man is sane; in fairness we ought to keep in mind that Theodore, as statesman and politician, is insane and irresponsible.” A year earlier, Olivia Clemons had died in Florence, Italy.\

Olivia was six years gone when the following item written by Twain appeared in The Ottowa Free Trader in 1911. William Howard Taft, a conservative Republican and a great disappointment to Roosevelt, had just been sworn in as president: “Astronomers assure us that the attraction of gravitation on the surface of the sun is twenty-eight times as powerful as is the force at the surface of the earth, that an object which weighs 217 pounds elsewhere would weigh 6,000 pounds there. For seven years this country has lain smothering under a burden like that, an incubus representing in the person of President Roosevelt, the difference between 217 pounds and 6,000.

“Thanks be we got rid of this disastrous burden day before yesterday, at last -- forever, probably not. Probably for only a brief breathing spell, wherein under Mr. Taft, we may hope to get back some of our health. Four years from now we may expect to have Mr. Roosevelt sitting on us again, with his twenty-eight times the weight of any other Presidential burden that a hostile Providence could impose upon us for our sins.

“Our people have adored this showy charlatan as perhaps no impostor of his brood has been adored since the golden calf; so it is to be expected that the nation will want him back again after he is done hunting other wild animals heroically in Africa, with the safeguards and advertising equipment of a park of artillery and a brass band.”

And indeed, Roosevelt, frustrated with the non-progressive policies of Taft, did make a showy comeback a year later as a “Bull-Moose” candidate for president. William McKinley’s Vice President, Roosevelt became president following McKinley’s assassination, was elected to a full term in 1904 and vigorously promoted a progressive agenda. The person Roosevelt groomed for president, Taft, is now heralded as a conservative, politically pretty much Roosevelt’s opposite number. Frustrated with Taft, Roosevelt sought the Republican endorsement for president in 1912, failed in his effort and, storming out of the Republican convention, founded the progressive “Bull Moose” party, ultimately throwing the presidency to Woodrow Wilson, a progressive Democrat.\

Twain would have witnessed some of this drama in his rear view mirror, and his reaction to Roosevelt was both splenetic and humorously titillating. Three years before he died, Twain dictated the following assessment for his autobiography: “Mr. Roosevelt is the Tom Sawyer of the political world of the twentieth century; always showing off; always hunting for a chance to show off; in his frenzied imagination, the Great Republic is a vast Barnum circus with him for a clown and the whole world for audience; he would go to Halifax for half a chance to show off and he would go to hell for a whole one.”

Perhaps the most read modern biography of Roosevelt is Theodore Rex, by Edmund Morris. Two paragraphs in the book mention Twain, who is quoted disparaging Roosevelt mildly only once: “Twain was never-the-less moved to express the misgivings of not a few thoughtful observers who wondered if a Roosevelt unrestrained might not become a Roosevelt moving too fast for his own good.” Morris embeds a Twain quote here: “’He [Roosevelt] flies from one thing to another with incredible dispatch… each act of his, and each opinion expressed, is likely to abolish or controvert some previous act or expressed opinion.’” This is a wordy way of saying that Twain thought Roosevelt a hypocrite; his real feelings about Roosevelt were much fiercer than that. In any case, Twain’s anti-Roosevelt vituperation is under-displayed in Morris’ book.

A Gilded Twain

Roosevelt was a type that challenged Twain’s temperamental disposition. H. L. Mencken approached the truth about Twain reverently when he wrote: “Instead of being a mere entertainer of the mob, he [Twain] was in fact a literary artist of the very highest skill and sophistication… he was a destructive satirist of the utmost pungency and relentlessness, and the most bitter critic of American platitude and delusion, whether social, political or religious, that ever lived.” Of course, Mencken’s appreciation is tinged with his own Nietzschean prejudices. Writers tend to regard as saintly other writers whose views can be forced into their own Procrustean beds.

Mencken notes that Twain’s comic mask had publicly been thrown off after Harpers Magazine had published The Mysterious Stranger and What Is Man?

Mencken lifts a quote from Twain’s preface: “The ideas in it are very simple, and reduced to elementals, two in number. The first is that man, save for a trace of volition that grows smaller and smaller the more it is analyzed, is a living machine — that nine-tenths of his acts are purely reflex, and that moral responsibility, and with it religion, are thus mere delusions. The second is that the only genuine human motive, like the only genuine dog motive or fish motive or protoplasm motive is self-interest — that altruism, for all its seeming potency in human concerns, is no more than a specious appearance — that the one unbroken effort of the organism is to promote its own comfort, welfare and survival…”

These determinist ideas, aggressively promoted by Thomas Huxley, sometimes called “Darwin’s Bulldog,” were throbbing in the public pulse during Twain’s own day. We do not know – and perhaps cannot know – whether Twain’s sentiments, as expressed above, are simply a “thought experiment” placed in the mind of a fictitious character or, more ominously, whether this dark vision of God and man represents Twain’s own world view. Nietzsche, we now know, read and liked Twain. But Twain came by Nietzsche indirectly, through a back door. George Bernard Shaw, a more rigorous Zarathustrian, yoked together both Twain and Nietzsche in a review of two translations of Nietzsche titled “Giving the Devil His Due,” only to dismiss Twain later, in a preface to Three Plays for Puritans, as a member of the Diabolonian Junior Varsity team.

Twain professed a lack of interest in Nietzsche, or indeed in any other philosopher. He drew his own philosophy, Twain insisted, “from the fountainhead… that is to say, the human race… Every man is in his person the whole human race … in myself I find in big or little proportion every quality and every defect that is findable in the mass of the race.”

Comparisons between Twain and Nietzsche lead, more often than not, into a philosophical snake pit. Aspiration is a more certain architect of character, and Twain’s aspirations mirror those of the Gilded Age and the Manchester School, a 19th Century movement that began in Manchester, England, whose most prominent proponents were Richard Cobden and John Bright. The school has more in common with modern conservativism than either modern liberalism or progressivism. The Manchester School carried into politics the theories of economic liberalism popularized by Adam Smith and Davin Hume: free trade, laissez-faire, pacifism, anti-slavery, freedom of the press, separation of church and state, and anti-colonialism.

No one can doubt that Twain was a fierce anti-colonialist. The Spanish-American War was a large stone in his shoe, and he was, one might say, instinctively wary of strong-man politicians, possibly because he was, like some important writers of his day, a superb psychologist who drew his perceptions, as did Dostoyevsky and Dickens, from a deep private well. The most important note of Manchester liberalism is its belief in free – non-government regulated – consensual relations of all groups at every level. Henry David Thoreau was shouting from the Manchurian rooftops when he said -- that government governs best which govern not at all.

It may be best to adopt a historical view of Twain and anchor him, as one sets a stone in its setting, in his own time. Twain wrote and rose to public prominence near the end of the La Belle Époque, roughly the Victorian age in Europe (1837-1901). In America, this period was called The Gilded Age, and it was Mark Twain himself who named the age in a lesser known book he wrote along with Charles Dudley Warner, published in 1873 and titled The Gilded Age: A Tale of Today.

Warner came from Puritan Massachusetts stock, practiced law in Chicago from 1856-1860, was assistant editor then editor of the Hartford Press, which later became The Hartford Courant, and also an editor for Harper’s Magazine.

The Gilded Age marked the period of rapid economic growth in America following the Civil War up to the turn of the century. And what a boom it was! The United States had come into its own. Millionaires were popping up on every street corner. And for the first time, the United States economically was outpacing Europe, torn as usual by its historic divisions. The rise of the progressive movement in the United States marked the end of the Gilded Age.

In 1884 so-called Bourbon Democrats elected Grover Cleveland to the presidency. It was the first time since 1856 that a Democrat had sat in the White House. The Bourbon Democrats, often contrasted with Republican Mugwumps, were very close in spirit to modem conservatives. Bourbon Democrats supported low tariffs, reductions in government spending and, most importantly, a laissez-faire government. Tarrifs, they argued, increased the cost of goods and subsidized government supported monopolies. They fiercely denounced imperialism and an expansionary overseas policy. Remind you of anyone?

“The mania for giving the Government power to meddle with the private affairs of cities or citizens is likely to cause endless trouble,” Twain wrote in a letter to Enterprise in 1866. “And there is great danger that our people will lose that independence of thought and action which is the cause of much of our greatness, and sink into the helplessness of the Frenchman or German who expects his government to feed him when hungry, clothe him when naked … and, in time, to regulate every act of humanity from the cradle to the tomb, including the manner in which he may seek future admission to paradise.”

Republicans, on the other hand, felt national prosperity depended upon an economy that produced high wages; they feared a flood of low priced goods from Europe would depress both wages and the burgeoning economy. The tariff , they thought, should be used as tool necessary to prevent the impending catastrophe.

The Gilded Age was brought to a stop by Progressivism, which began as a Prairie Populist movement shortly after the Civil War and flooded Teddy Roosevelt’s ambitious and fertile mind with dreams of glory. Roosevelt, the hero of San Juan Hill, was the first important progressive president. And Twain, who fulminated against the Gilded Age in the book he wrote with Warner, intensely disliked Roosevelt, the Spanish America War, US expansionist policies in the Philippines, monarchs of every shape and hue – most venomously, the Czar of Russia.

When Roosevelt, rejected by Republicans in favor of Howard Taft, now embraced as a conservative by modern American conservatives, went off to Africa on a safari – TR liked to kill things and share stuffed carcasses among his friends – Twain wrote that Zarathustra-on-the-hunt had gone off to Africa to “kill cows.” Roosevelt, hunting water buffaloes at the time, was not amused.

Progressives And Libertarians

Twain was a laissez faire child of the Gilded Age and – most importantly – an acerbic social critic and humorist. Fredric Bastiat, the father of libertarianism, also was a Manchester School liberal who, like Twain, was a suburb dialectician. In the modern period, Twain would be a libertarian and, as he was in his own day, a virulent opponent of what then was called, approvingly, muscular Christianity. It was from muscular Christianity that the progressive movement in America arose. The very notion of missionary Christianity was abhorrent to Twain, because he was an apostle of liberty as it pertains to individuals. Equally abhorrent was politics as a missionary activity.

Here is Bastiat on law officers before and after elections:

“When it is time to vote, apparently the voter is not to be asked for any guarantee of his wisdom. His will and capacity to choose wisely are taken for granted. Can the people be mistaken? Are we not living in an age of enlightenment? What! are the people always to be kept on leashes? Have they not won their rights by great effort and sacrifice? Have they not given ample proof of their intelligence and wisdom? Are they not adults? Are they not capable of judging for themselves? Do they not know what is best for themselves? Is there a class or a man who would be so bold as to set himself above the people, and judge and act for them? No, no, the people are and should be free. They desire to manage their own affairs, and they shall do so.\

“But when the legislator is finally elected — ah! then indeed does the tone of his speech undergo a radical change. The people are returned to passiveness, inertness, and unconsciousness; the legislator enters into omnipotence. Now it is for him to initiate, to direct, to propel, and to organize. Mankind has only to submit; the hour of despotism has struck. We now observe this fatal idea: The people who, during the election, were so wise, so moral, and so perfect, now have no tendencies whatever; or if they have any, they are tendencies that lead downward into degradation.”

And Twain: “No country can be well governed unless its citizens as a body keep religiously before their minds that they are the guardians of the law and that the law officers are only the machinery for its execution, nothing more.”

And here is Twain in the Galaxy Magazine telling what Huck Finn once styled one of Twain’s stretchers: “I shall not often meddle with politics, because we have a political Editor who is already excellent and only needs to serve a term or two in the penitentiary to be perfect.”

Twain did meddle with politics, and it did get him into trouble. But isn’t trouble the theatre in which a comic talent like Twain performs? The question remains: To what extent should we take comedy seriously? Does the comic lose authority by speaking behind a mask of humor?

On Christmas Eve 1909, Twain had returned four days earlier from Bermuda to his Redding home, “Stormfield.” Hours earlier, Twain’s youngest daughter, Jean, had drowned in a bathtub from a heart attack that may have been related to her epilepsy.

On Christmas Eve, Twain wrote the following eulogy:

“I lost Susy thirteen years ago; I lost her mother – her incomparable mother! –five and a half years ago; Clara has gone away to live in Europe; and now I have lost Jean. How poor I am, who was once so rich! Seven months ago Mr. Roger died – one of the best friends I ever had, and the nearest perfect, as man and gentleman, I have yet met among my race; within the last six weeks Gilder has passed away, and Laffan–old, old friends of mine. Jean lies yonder, I sit here; we are strangers under our own roof; we kissed hands good-by at this door last night–and it was forever, we never suspecting it. She lies there, and I sit here–writing, busying myself, to keep my heart from breaking. How dazzlingly the sunshine is flooding the hills around! It is like a mockery.”

Let others say Twain was not to be taken seriously. I will not say it.

Don Pesci is a Vernon, Conn.-based essayist.

Don Pesci: Chris Powell has been very important to Connecticut

I happen to be writing something on Mark Twain’s politics, and I couldn’t help but wonder what he might have thought rather than written – for Twain was fairly cautious, some would say over-cautious, while his wife and censor Olivia was still alive – about recent Connecticut politics.

Surely Twain would have noticed that the flight of progressive politicians from their sinecures have followed the flight of businesses and entrepreneurial capital from his beloved state. There’s got to be some heavy levity, Twain’s specialty, in there somewhere. Not even Olivia, the keeper of Twain’s reputation, could have prevented him from poking fun at Connecticut’s political Grand Guignol. Following a fatal dip in the polls, Gov. Dannel Malloy has chosen not to run again, and he has been followed out the door by his lieutenant governor, a promising Democrat gubernatorial prospect who has not spent time in prison, Comptroller Kevin Lembo, Atty. Gen. George Jepsen, and other Democrat celebrities, all banging their tushies, frantically attempting to put out pant fires.

We don’t have Twain with us anymore. But Chris Powell, whose retirement from his job as managing editor of the Journal Inquirer, in Manchester, Conn., is still pending, will be with us for some time to come. Though he will be leaving the paper as a regular employee after 50 years, Powell will maintain his column – good news for the good guys, bad news for the bad guys.

State Sen. Joe Markley said on Facebook that Powell was Connecticut’s “indispensable man,” and this flushed out some doubters. One would think in the era of President Trump, country and state would have gotten used to a little hyperbole. A little rich, one guy thought. We hauled that guy off to a dark corner and gave him a public thrashing, because Powell really is the indispensable man. It’s OK; you can do this sort of thing on Facebook and, if you are president of the United States, on Twitter, which has become a kind of tumbril used to transport distasteful politicians to the guillotine.

I provided half a dozen items -- all written by me; interviews with Powell on Connecticut Commentary, mentions of him in past columns, his indispensable review of Lowell Weicker’s autobiography Maverick, which Powell titled “Mr. Bluster Saves The World,” and such like -- to support Markley’s thesis.

At the same time, I received from my nephew Craig Tobey, who is living in California – please don’t ask me why – a message on LinkedIn congratulating me for having spent 38 years writing columns. Powell is wholly responsible for this. So, I wrote Craig back saying “Thanks. It’s a long time to have been writing on water.”

When the waves break, when time passes, all of it is writing on water. You try to say some things that will stay fresh on the shelf, and Powell is better at this than most. He’s quotable and memorable, always the sign of a superior intellect. And he likes all the right thinkers -- Frédéric Bastiat, for instance, and G.K. Chesterton. Tethered to either of these sane anchors, you cannot wander far from the truth.

There are, as we know, two kinds of truths, pleasant and unpleasant -- mine and yours. It is the unpleasant but necessary truths we all instinctively retreat from.

We all are servants of the truth, not its masters. Writing in “The Examiner” in 1710, Jonathan Swift said it best: “Besides, as the vilest writer has his readers, so the greatest liar has his believers; and it often happens, that if a lie be believ’d only for an hour, it has done its work, and there is no farther occasion for it. Falsehood flies, and the truth comes limping after it; so that when men come to be undeceiv’d, it is too late; the jest is over, and the tale has had its effect.”

It is the business of honest journalism to see to it that the truth is not washed away by lies. To lie is to say the thing that is not, and journalists should avoid this too common practice like the plague. For fifty years in journalism, that has been Powell’s honorable trade. He will never receive a Pulitzer – neither did Bill Buckley, astonishingly – but he has retired from the paper only, and during his long haul he has kept faith with Joseph Pulitzer’s ever-fresh observation that “good journalists should have no friends” -- in the political world, I should hasten to mention. Isn’t it uplifting to think that we will have Powell with us to kick around threadbare politicians a bit more?

Don Pesci is a Vernon, Conn.-based essayist, and, like Chris Powell, a frequent contributor to New England Diary.

Don Pesci: Twain, TR and imperialism

Mark Twain during TR's administration.

Theodore Roosevelt on Twain – “I wish I could skin Mark Twain alive.”

Twain on Roosevelt – “We have had no President before who was destitute of self-respect for his high office. We have had no President before who was not a gentleman; we have had no President before who was intended for a butcher, a dive-keeper or a bully.”

VERNON, Conn.

Occasionally, columnists back up against a thorny subject much in the way an innocent traveler in the woods backs up against a porcupine. The collision is often painful for both the porcupine and the columnist.

Although the deathless struggle between Twain, a longtime Connecticut resident, and TR has been known for more than a century, it is rarely mentioned in print. Twain scholars know that Twain and TR were natural enemies on the matter of American imperialism, TR favoring the civilizing benefits of imperialism, always good for the native population and American businesses on the hunt for overseas markets, and Twain opposing it – strenuously.

TR’s animal spirits were aroused by “killing things,” as his political opponents said, and the notion that the American idea should extend beyond its Monroe Doctrine borders to Hawaii, during Twain’s time, still an island paradise controlled by the native population, Cuba and the Philippines, both part of the far-flung Spanish Empire, and wherever else three prominent American expansionists -- Theodore Roosevelt, whose ambitions for personal glory knew no bounds, William Randolph Hearst, a pro-imperialist newspaper owner, and Massachusetts Sen. Henry Cabot Lodge, a close friend of TR and a shaker and mover in Congress -- though that the United States should extend its reach in the world.

Twain was still in Europe when a diffident President William McKinley, largely at the urging of pro-imperialist, ''civilizing'' forces in the United States, ordered the U.S. Navy into Cuba, there to support rebel groups agitating for democracy and freedom from Spanish rule. We all recall Hearst’s war-whoop: “Remember the Maine; To Hell With Spain.”

The Maine went down in Havana Harbor, a sinking likely caused, it was revealed seventy years after the event, by an internal fire that had ignited explosives aboard the war ship. At the time, Hearst, dollar signs always in his eyes, happily circulated the notion that the Maine had been sunk by the Spanish and said so in many lurid and sensational stories printed in his paper. Roosevelt went off as a colonel to command a regiment in Cuba and later stormed San Juan Hill with his “Rough Riders.” The Philippians, Guam especially, was set free of the Spanish navy. America’s imperial outreach was intended to Christianize and civilize savage nations, open markets to U.S. goods and announce brashly to the world that, in an era of colonializing powers, the United States had come of age. The imperialists had the stage pretty much to themselves, and then Twain, who at first supported the Cuban adventure because he thought it might help a nation struggling against a colonial power to attain independence, returned home – with a pen dipped in the fires of Hell.

TR found that San Juan Hill was easier to storm than Twain who, to his last breath, insisted as a matter of principle, along with John Adams, that while the United States is a friend to democracy everywhere, it is the custodian only of its own.

The Twain-TR struggle continues today under different battle flags. The presence of a resurgent Islam in modern times has changed the calculus somewhat. Among other things, a resurgent Islam is intent upon 1) sweeping Western influence – religious, cultural and legal -- including democracy, from its own sphere of influence, 2) restoring a sphere of influence it held for roughly 1,500 years as an imperial power, and 3) bringing all other faiths and social orders under Islam at the point of a sword.

The contest between a resurgent Islam and a West that has internally surrendered to a superior spiritual force – demographics show that Islam will out-produce the West in the only product that really matters, children, in the not too distant future – places before those of us in the United States who believe Twain got the better of the argument over TR the age old questions: Without a more than equal countervailing force, how does the West preserve itself from destruction?

Can there be a difference between imperialism and intervention? And has there ever been in the history of the world a non-imperialist nation whose mission is the preservation and extension of Western Cvilization?

Don Pesci is a writer (mostly on politics) who lives in Vernon, Conn.

Annual reminder

"King Lear and the Fool in the Storm,'' by William Dyce.

"The first of April is the day we remember what we are the other 364 days of the year."

-- Mark Twain

More than enough of it

Adapted from Robert Whitcomb's "Digital Diary'' column in GoLocal24.com

“Yes, one of the brightest gems in the New England weather is the dazzling uncertainty of it. There is only one thing certain about it: You are certain there is going to be plenty of weather.”

-- Mark Twain lived many years in Connecticut but it was said that his favorite place in late life was Dublin, N.H. That's New England’s highest town and was once home of Beech Hill Farm, a famous drying-out clinic and retreat for mostly affluent alcoholics. It still hosts Yankee Publishing Inc., publisher of Yankee Magazine and the Old Farmer's Almanac.

And so we go into another spring, up and down weatherwise but trending the right way. First the flowers that can take freezing and thawing and refreezing – the crocuses and the snowdrops. Then the somewhat less hardy daffodils and the tulips.

It will be “Mud Time’’ for a few weeks in New England’s north country. And, of course, it’s pothole season!

A lot of folks are so impatient for spring that they strip down to shorts and T-shirts and wander around outside when it’s still in the forties, in a triumph of hope over experience.

Plant the radishes first!

The buds on the trees swell and then seem to almost explode on one afternoon in late April or early May—that is, except right along the coast, where the cold water delays the season as the warmed-up water delays winter late in the year. As visitors to Fenway Park know “Boston’s famous east wind’’ can drive down the temperature of a mid-April day by 20 degrees in 15 minutes.

Then comes that hot, humid day in late May or early June when the lushness is almost tropical. In New Hampshire when I lived there, it sometimes seemed as if winter ended one day and summer started the next.

Spring seems at once the real start of the year, at least of the natural year, as well as its ending, a feeling that for most people goes back to their memories of the school year’s approaching end.

This recalls the Rodgers & Hammerstein song "It Might as Well Be Spring,'' whose last lines are:

"I haven't seen a crocus or a rosebud or a robin on the wing

But I feel so gay in a melancholy way

That it might as well be Spring .

It might as well be spring….''

Warning! This uses the old-fashioned meaning of "gay''.

136 ways to confuse

"In the spring {in New England} I have counted one hundred and thirty-six different kinds of weather inside of four and twenty hours."

-- Mark Twain

Twain lived for many years in Hartford, Conn., although his favorite place in the world might have been gorgeous Dublin, N.H., near Mount Monadnock. I became very familiar with the town because I had to drive my manic-depressive alcoholic mother there on numerous occasions to be dried out at a famous place for such problematic work known as Beech Hill Farm, on the top of a mountain above the village. Further down the hill was Yankee Inc., which still publishes Yankee Magazine and the Old Farmer's Almanac.

Dublin remains a good place from which to watch the vagaries of New England weather.

-- Robert Whitcomb

James P. Freeman: The style of George F. Will

“The most durable thing in writing is style, and style is the

most valuable investment a writer can make with his time.”

For those who follow closely or casually the commentator and columnist George Will, most are probably left with the impression of his erudite conservative views on the written page and his be-spectacled, bow-tied, urbane appearances on cable television. For some, however, it is Will’s unique style and sensibility that elevates him above his peers. That combination arguably makes him the most influential writer in America.

“A columnist for only a year,” noted James J. Kilpatrick in his 1984 book, The Writer’s Art, when Will wrote in 1975 “a splendid piece” on Patty Hearst. “Her arrest, he informed us, ‘provided a coda to a decade of political infantilism, the exegesis of which could be comprehended as a manifestation of bourgeois Weltanschauung.’ With that out of his system, George went on to win a Pulitzer Prize for commentary and to become a polished and literate essayist…”

That year he also described the rock band Led Zeppelin, as it descended into the nation’s capital, as “one of society’s vigorously vibrating ganglions.” His early work was cast in original, descriptively smoldering tones, a kind of literary Stradivari -- pitch perfect with rich resonance.

He began writing regularly in the early 1970s as Washington Editor for National Review, under the watchful eye of its founder, William F. Buckley Jr.; under the storm clouds of Watergate Will became an early outspoken critic of the Nixon administration. On Jan. 1, 1974 he became a syndicated columnist for The Washington Post; 40 years later the column appears in more than 450 newspapers. In 1976 he started a bi-weekly essay on the back page of Newsweek magazine which ran for over 30 years.

After 25 years, and a rich sediment of source material from which to study, in 1999, writing for the Ashbrook Center. at Ashland University, Steven Hayward noted Will’s “prose style combine three elements.” One, “there is the sheer clarity and aphoristic quality of his prose.” His “one sentence distillations of a larger body of thought can be found in reading every column.” Two, “Will is a superb narrative story-teller, a rarity among opinion journalists.” Three, he writes with a “dry understated, wit, also rare among opinion journalists whose prose seldom deviates from the monotone seriousness of the overly earnest.”

Conceivably, then, Hayward read this 1977 gem:

Unfortunately, my favorite delight (chocolate-coated vanilla ice cream flecked with nuts) bears the unutterable name “Hot Fudge Nutty Buddy,” an example of the plague of cuteness in commerce. There are some things a gentleman simply will not do, and one is announce in public a desire for a ‘Nutty buddy.’ So I usually settle for a plain vanilla cone.

That year he was awarded the Pulitzer Prize for distinguished commentary. The Commentary Writing Jury Report concluded that, “Will combines a scholarly approach to commentary with wry humor. His writing style is clear and to the point. His arguments and analysis are forceful and easy to understand…”

Fortune Magazine described his collection of columns in 1982’s The Pursuit of Virtue and Other Tory Notions, as “a marvel of style, personality, character, learning and intelligence.” And Commentary Magazine noted “a stylistic signature so immediately recognizeable.”

A genome sequencing of Will’s compositions reveals certain attributes: two word alliterations; one sentence words puncture and punctuate longer sentences; and, despite the ice cream quotation above, rarely will he employ the use of the first-person pronoun “I.” A droll deprecation acts as an effective counter balances to weighty matters and may in fact enhance arguments presented in his work. It is also lyrical -- a certain poetry to the prose within the boundaries a standard 750 word column.

Recall a recent column about Cuba as it offers a simple example. “The permanent embargo was imposed in 1962 in the hope of achieving, among other things, regime change. Well.”

Last spring, Will was interviewed by radio personality Steve Richards for his program Speaking of Writers. He was asked something he rarely is asked about: his writing process and routine. Will explained, “I absolutely love to write” and described the activity as a “physical, tactile pleasure;” the feeling of thoughts becoming words. “A lot of reading and research goes into” writing 100 columns a year, he allows.

Will used to write “the old–fashioned way,” in long hand with a fountain pen. That all changed in February 1994, when, after a taping of the Sunday TV Program The Week, he broke his right arm. Ever since, he has written on a computer but he has not brought himself – yet – to twitter and tweeting. The focus always remains on content over transmission.

The best advice ever given to him was uttered by Mark Twain, who advised to do three things: “Write, write, write.” As for dispensing advice for writers, Will instructs: “Find models to emulate,” and it is important one “gets a sense to have a style.” It confirms what William Zinsser, author of On Writing Well, said: “Writing is learned by imitation; we all need models.”

And Will’s models? “This columnist has had two, columnist Murray Kempton and novelist P.G. Wodehouse.”

For me, such an honor belongs to two writers as well: George Will and U2’s Bono. A strange alloy, perhaps, unique and, at times, seemingly incompatible. But as Will reminds us, “style reflects sensibility.”

James P. Freeman is a Cape Cod-based writer