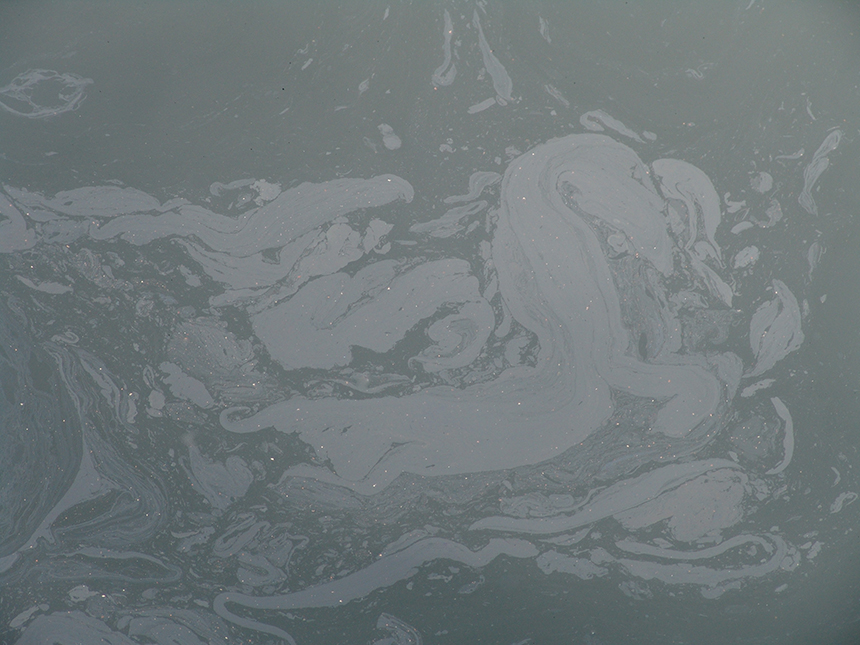

A weirdly beautiful oil sheen on the waters of New Bedford Harbor.

Photo by Frank Carini

From ecoRI News (ecori.org)

NEW BEDFORD, Mass.

Oil sheens have long stained one of the country’s most historic harbors. Visits by tourists to enjoy seaside sights and sample local seafood at harborside restaurants can be marred by these distinct marine markings.

In late February, the Coast Guard and Massachusetts Department of Environmental Protection (DEP) were called to New Bedford Harbor after oil was spotted lapping up against the docks and fishing vessels at Leonard’s Wharf. About two drums worth of oil was recovered. The source was never identified.

Six months later, in mid-August, Coast Guard crews oversaw a fuel-spill cleanup after a tugboat captain called the Coast Guard to report a 62-foot fishing vessel had sunk and was discharging fuel. The vessel carried about 7,000 gallons of fuel. The spill spread some 1.5 miles to Fairhaven.

Since 2010, the marine-industrial harbor has seen at least one recorded oil spill every month, according to the Buzzards Bay Coalition.

“New Bedford Harbor has a chronic oil spill problem,” a Coast Guard press release noted earlier this year.

The harbor’s spill problem doesn’t mix well with a 2009 study titled “Evaluation of Marine Oil Spill Threat to Massachusetts Coastal Communities,” which noted that, “New Bedford Harbor reported the highest number of vessels, with a fleet size of 500, many of which are large offshore scallopers and draggers. The GPE (gallons of petroleum exposure) for the New Bedford Harbor fishing fleet is estimated at 7,500,000 gallons, more than three times the next largest amount.”

Much of the Port of New Bedford’s petroleum problems can be traced back to the accidental and intentional dumping of oil via bilge water from commercial fishing vessels. Fuel and oil can leak into a vessel’s bilge, or the engine block can be deliberately drained into the bilge. This mixture of water, oil and fuel is released into the marine environment when an automatic bilge pump turns on, or when a boat owner deliberately breaks the law and pumps the bilge out in the harbor or out at sea. It's been a problem for decades.

These chronic oil discharges have been a longtime concern for Joe Costa, executive director of the Buzzards Bay National Estuary Program. The 1991 Comprehensive Conservation and Management Plan (CCMP) for Buzzards Bay highlighted the problem. It remained an identified concern in the 2013 Buzzards Bay CCMP.

It remains a concern today. Since 2016, more than 70 oil sheens have been reported in the water between New Bedford and Fairhaven. In most cases, no one steps forward to claim responsibility, according to the Coast Guard’s New Bedford field office.

Port director Edward Anthes-Washburn acknowledged that the problem is exacerbated when ships pump out contaminated bilge water.

“We have a concentration of vessels like nowhere else on the East Coast,” he said, noting that the working harbor is the home port of 300 fishing vessels and services another 200. “There’s no doubt bilge water is an issue. We’re working on education, and reporting spills.”

Anthes-Washburn, who also serves as the executive director of the New Bedford Harbor Development Commission (HDC), noted that fuel barges operated by oil retailers pump out waste oil for free, as long as it’s not contaminated by seawater.

And therein lies the real issue: too many owners fail to properly maintain their vessels, some of which are 20 to 30 years old. Advocates for a cleaner harbor believe the city needs to be more actively engaged in implementing a solution.

For instance, the HDC’s Fishing for Energy program collects derelict fishing nets and burns them for fuel. But the program doesn’t accept hazardous waste such as used oil contaminated by salt water.

“This problem has been worked on for 30 years and the ending is always the same: nothing gets done,” said Dan Crafton, section chief of emergency response for DEP’s Lakeville, Mass.-based unit. “The city doesn’t want to do anything to increase the burden on fishermen. But there are necessary components to running a clean harbor.”

Slow motion

As far back as the early 1990s, the reduction of discharges of oil and other hydrocarbons into New Bedford Harbor was identified as a high priority. The 1991 Buzzards Bay CCMP noted:

“Commercial fishing vessels, which operate mostly out of New Bedford but also Westport, usually have their engine oil changed (10-120 gallons per boat) after practically every trip. It is believed that the inconvenience and the expense (about 30 cents per gallon) of safely disposing of waste oil has resulted in a number of boat operators blatantly dumping oil into the Bay or offshore waters.”

The 270-page report also noted that, “Although this is illegal, it is difficult to document violations and hence take enforcement actions against the appropriate fishing boats.”

A January 1993 report titled “New Bedford Harbor Marine Pump-Out Facilities Study” and prepared for the HDC by HMM Associates Inc. noted that the disposal of vessel-generated waste oil “is unquestionably the single most important water quality protection initiative that must be implemented by municipal authorities if advances in water quality improvements are to be made within the harbor.”

The report also noted that the “unknown fate of over 252,000 gallons of engine waste oil known to be generated by the home fleet and not collected, is just too important to ignore.”

In 2000, Buzzards Bay National Estuary Program's Costa wrote a proposal titled A Boat Waste Oil Recovery Program for New Bedford Harbor to address the problem and received grant money from two sources. However, the initiative, which included building a bilge-water-oil separation facility along New Bedford’s working waterfront, failed to gain traction, due in large part to a lack of support from local officials. Costa ended up returning the grant money.

Crafton said the city isn't interested in a waterfront bilge-water-oil separator, even if the state funded the upfront costs. The city would have had to provide some operational funding. The cost to boaters to properly dispose of waste oil is about 50 cents a gallon, according to Crafton.

“Jiffy Lube charges car owners to dispose of their waste oil,” he said. “It’s harder to dump oil on the ground and get away with it. Most spills in the harbor happen at night, not during the day. People need to be more environmentally aware.”

Crafton also noted that DEP hasn't been able to find a private property owner interested in hosting a separator facility.

ecoRI News contacted the mayor’s office, but comment for this story was left to the HDC, a city agency. Mayor Jonathan Mitchell is the chairman of the HDC Commissioners.

“Our grant request to DEP for an oil recovery facility will address one major remaining source identified in the CCMP, the accidental and sometimes intentional dumping of tens or hundreds of thousands of oil by commercial vessels via bilge water,” according to Costa’s 17-year-old proposal. “The net environmental benefit of funding this initiative will be the prevention of 100,000 of gallons of oil and hydrocarbons from entering the coastal environment.”

The plan was specifically designed to eliminate “imposing oil disposal costs to an economically disadvantaged fishing industry.” Besides building a bilge-water-oil separation facility, the plan also proposed implementing an oil-recovery recycling program to provide easy and safe disposal of boat engine waste oil, a multilingual outreach/education program, and providing training and assistance to oil retailers.

The 1993 HMM Associates study recommended eight specific actions to address the improper disposal of waste oil, from adopting local regulations requiring oil-free bilges in commercial vessels to creating a private commercial service that would pump out waste oil from commercial vessels free of charge.

Costa’s 2000 proposal noted “little was done to implement these recommendations.” Costa estimated that as much as 60,000 to 120,000 gallons of waste oil are dumped, leaked and spilled into local waters annually by New Bedford Harbor’s commercial fishing fleet.

Today, nearly two decades later, New Bedford’s fishing fleet doesn’t have as many vessels and more boat owners are recycling waste oil properly. But a significant amount of used boat oil, which is considered hazardous waste, is still unnecessarily finding its way into New Bedford Harbor and Buzzards Bay.

Anthes-Washburn said the HDC doesn’t focus on the enforcement of state and federal regulations. He noted that the municipal agency is focused foremost on keeping its customers, the port’s commercial fishing fleet, safe.

“We report everything we see,” he said. “The fleet knows law enforcement is looking at it.”

Those concerned about this marine hydrocarbon problem point to several factors: no identified source or responsible party; poor waste oil management practices; underutilized disposal options; reluctance to report spills; lack of awareness.

“We want to work with fishermen, not against them,” Crafton said. “We’re not trying to harm the fishing industry.”

Addressing the problem

It’s been a while since the practice of pumping contaminated water from the bilges of fishing boats into the ocean has been legal. Under the Federal Water Pollution Control Act, no amount of oil is allowed to be pumped into the sea — understandable, since a cup of oil can create a sheen the size of a football field.

Lt. Lynn Schrayshuen, the Coast Guard’s New Bedford unit supervisor, and her Marine Safety Detachment team patrol New Bedford Harbor regularly looking for spilled, leaked or dumped oil. When an oil sheen is discovered, or reported, the team investigates to determine if it is recoverable, and collects a sample.

Collected samples are taken to the Coast Guard Marine Safety Lab in New London, Conn., for testing. The samples are processed and cleaned of organic material until only oil is left. If the oil fingerprint from the sheen matches the fingerprint from another bilge sample, the team may be able to identify a responsible party.

But the illegal practice, including the common practice of pumping water out from the bilge and then stopping when oil enters the stream, remains a considerable problem for New Bedford Harbor, the city’s coastline, and across the way in Fairhaven.

To deal with the problem, DEP and the HDC ran a pilot program called Clean Bilge New Bedford that offered free pump-outs and inspections to commercial fishing vessels to prevent oil spills, and featured outreach and educational efforts. The 1.5-year pilot, which was state funded, ended earlier this year. During the pilot program, 174 vessels had their bilge pumped out once and 39 had their bilge pumped out at least twice. A total of 58,666 gallons of oily bilge water was recovered — 18,387 gallons, or 31 percent, was oil.

“This is a real issue,” Crafton said. “What would people think if they knew the number one fishing port in the United States is the same place where waste oil is being dumped?”

Frank Carini is editor of ecoRI News (ecori.org)

·