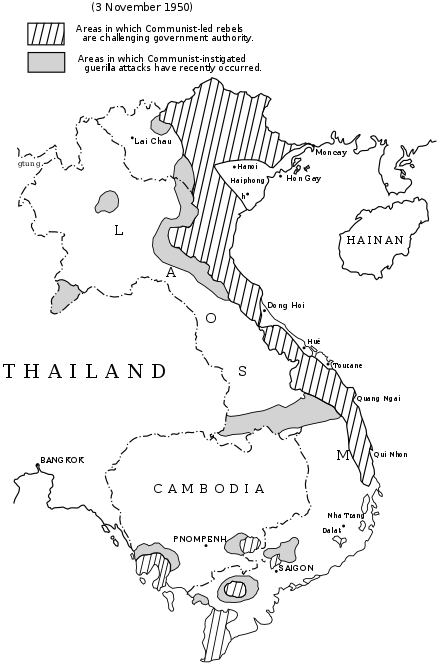

A CIA map of dissident activities in Indochina, published as part of "The Pentagon Papers.''

I read somewhere that director Steven Spielberg says he does not read books. However Spielberg gets his information, he has gotten the newspaper trade right, very right in The Post.

It is one of the best films about the inside workings of a newspaper.

It involves the decision, reached between the publisher of The Washington Post and its editor in June 1971, to publish the collection of secret documents detailing the hopelessness of the Vietnam War from 1964 onwards. Collectively, these are known as "The Pentagon Papers''. They showed conclusively that the government had always known that the war was a losing proposition and covered it up. They also, it must be said, showed that the media, for all the reporters crawling over South Vietnam, did not know what the government knew. The story was missed.

This is a film apposite for our time, both as an illustration of the duplicity of governments, in this case under Democratic and Republican administrations (Eisenhower, Kennedy, Johnson and Nixon), and the key role of a free press in checking government.

It is also a shot in the arm for the newspaper trade, which is under attack frontally from President Trump and his merry band of besmirches and from financial undermining, occasioned by the flight of advertisers to the Internet.

This is a work that is not only fine entertainment but also very accurate. I can make that statement because I was working at The Washington Post at the time and I knew the protagonists, Ben Bradlee, the storied editor, and his publisher, Katharine Graham.

Watching this film I marveled at how much Tom Hanks looked like Bradlee, given he was a little heavier than Bradlee, who delighted in looking like David Niven playing a jewel thief in the South of France. Graham, always called “Mrs. Graham,” is very well replicated by Meryl Streep, although Graham was a little taller and maybe a smidgeon more imperial.

It is Hanks's portrayal of Bradlee that floored me. He is Bradlee, the boulevardier who used profanity as a tool and could drop an expletive as though it were a precision-guided munition.

Graham and Bradlee risked prison to publish the papers, as did editor Abe Rosenthal and publisher Arthur Sulzberger, at The New York Times. You will come out of this movie feeling good about the First Amendment, good about newspapers, bad about governments.

You will be very glad the film industry has a talent as great as Spielberg.

A lesser director might have settled for getting Graham and Bradlee right, but Rosenthal and Ben Bagdikian, The Post's national editor, too? That is meticulous.

Even the atmosphere of the composing room, back when linotype machines clattered and skilled fingers spaced and secured the little lines of type, is authentic. Hot-type aficionados, like me, rejoice.

Those were the days. And this is the movie.

The Night That Paul Bocuse Messed Up

Paul Bocuse, widely described as the most important chef of the last century, has died at 91. He invented "nouvelle cuisine,'' a new form of high French cooking. More fresh produce, lighter sauces and the imaginative pairing of flavors and ingredients marked it. It is reflected in nearly all the fashionable restaurants of today and has influenced chefs around the world.

I was lucky enough to be a guest, along with 11 other diners, at the great man’s legendary restaurant L’Augberge du Pont de Collonges, near Lyon. It was an experience that foodies dream about. The restaurant had an open kitchen of the kind that came to be associated with California: You could watch the chefs work. Bocuse and his wife both stopped by our table.

The food? Exceptional – even though one order got lost. The order just didn’t make it out of the kitchen, and the result was the whole restaurant felt the shame.

When we left one of the captains followed me -- thinking that I might be a food writer, which I was not -- to apologize. He said simply, “Please believe me, we usually do better.”

Indeed, the great chef did, and in doing so changed the world of fine dining.

When I have told this story to people who know more about Bocuse and his legacy than I do, they tell me I may be the only person who left with an apology: a three-star Michelin apology. I am humbled.

The Things They Say

"Facts are better than dreams.''

-- Winston Churchill

Llewellyn King, executive producer and host of White House Chronicle, on PBS, is a veteran publisher, editor, columnist and international business consultant. He's based in Rhode Island and Washington, D.C.