From The New England Journal of Higher Education, a service of The New England Board of Higher Education (nebhe.org)

BOSTON

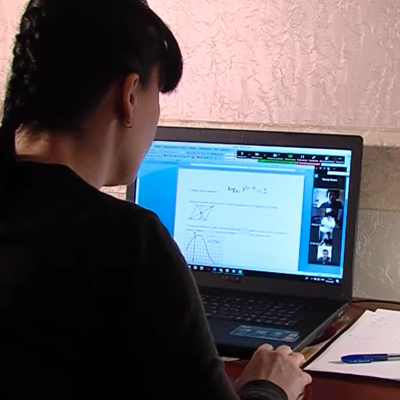

The majority of college students were largely disappointed by remote learning this past spring, with many reporting a strong preference for in-person instruction. Bearing in mind the low expectations that many students carried into online courses this fall, what advice can we give to help them succeed in this final month? As colleges across New England and the country continue to announce spring plans that include online courses, what can we share to prepare students for success in 2021?

While the internet is saturated with “hacks” for online learning, I want to connect you with the best experts I know: Students.

Since March, the Persistence Plus mobile nudging support platform has asked more than 25,000 students from both two- and four-year institutions about their experiences with remote learning. Specifically, we gathered their advice about how to excel in this format, and I saw four key themes emerge. I have also paired their insights with science-based exercises that can be shared with students to bolster their motivation and improve their performance in online courses.

1. Set a schedule. The most frequently offered advice was the need to set a regular schedule—especially in asynchronous courses—and stick to it. Several students mentioned examining the syllabus for major assignments and noting due dates in advance, working ahead on those assignments to the extent possible and regularly checking email and the course website. Here’s some of what they said:

“Make a schedule for classes, study time, completion of assignments, breaks, etc., and build enough discipline to stick to the schedule.”

“Make a schedule for time to study. Prioritize due dates on assignments and exams. It is not as difficult as you may think. Discipline and focus is key.”

“Work as far ahead as possible, get assignments done as soon as you get them so you don’t have to worry about it, and set a scheduled time each day to work on school.”

“Write everything down and log into your classes and email to check for new reminders and announcements every day.”

One way that students can go beyond just setting a schedule is with “if-then” plans. We all naturally underestimate how long it takes to complete projects (known as the planning fallacy). To counteract this optimism, students can make very specific plans for when and where they will work on assignments (for example, “I will read Chapter 1 at the dining room table after my daughter goes to sleep on Wednesday night.”) The more specific they are, the more likely they are to follow through.

Yet the best-laid schemes of mice and men oft go awry. Students should also develop contingency plans for common obstacles (such as “If my daughter doesn’t fall asleep by 9 p.m., then I will read Chapter 1 before she wakes up the next morning.”) No one can foresee the future, but anticipating the most likely problems and pre-designing solutions will help students stay on track. You can facilitate students’ if-then plans by prompting them to complete the exercise via an email, a poll within your institution’s learning management system, or even providing space in the syllabus to craft if-then plans for each big assignment.

2. Create a study space. Students noted how important it is to have a quiet, peaceful (but not too relaxing!) area for schoolwork. The goal of such a space is to create focus without inducing grogginess. They suggested:

“Find a place where you can be composed and stay focused with your priorities.”

“If you can, set aside someplace that is specially for school work so that you can focus when doing work and then relax when you go to bed (if you only have space in your bedroom then just make sure not to do work on your bed, work only on your desk).”

“Find a place in your home to go that is designated to your studies.”

“Don’t attend virtual classes in bed! Try working at a table or desk for effective productivity. Working in your bed allows you to be too comfortable and can cause you to fall asleep or lose focus.”

Given the COVID-19 pandemic, this area is most likely within students’ homes. But as we all know, our homes are often crowded with partners, children, parents and roommates. One advantage of a dedicated space is that it sends a signal that this person is studying and shouldn’t be interrupted. Moreover, a regular study space takes advantage of state-dependent memory. When you learn something, cues from the environment become associated with it: the feel of your chair, the smell of the room, the taste of your coffee, even your mood at that moment. If students put themselves into those same circumstances when they need to recall that information (i.e. for the exam), they’ll be more likely to remember.

3. Ask for help. We heard over and over that students must reach out for help, especially from their professors, if they get stuck. If you’re a professor but you might be difficult to reach (you’re dealing with plenty of crises too!) build a system that makes it easy for students to connect with other faculty, former students, campus tutors, tech support and each other. Students advised:

“Don’t be afraid to email professors and/or classmates/peers for understanding of the coursework and/or additional assistance.”

“Professors make it very easy, they work with you and they provide all the resources you need to be successful. Don’t forget to ask questions.”

“Make group messages with your peers so you can keep each other on track, and ask each other questions.”

“Don’t be afraid to reach out to classmates and ask for help. Everyone is going through it together and supporting each other through it is what makes it work.”

Asking for help makes some students feel nervous or embarrassed. One way to circumvent those feelings is to use simple role reversal. Instead of asking someone else for advice, students can imagine that one of their classmates came to them with the same issue. Students can then consider what they would advise their peer to do, or whom they would point them to for help. This role-playing can make students less anxious by approaching their own problem from a neutral perspective, make them feel more empowered, and help them generate potential solutions that they may not otherwise see.

4. Be accountable. Finally, students noted that success in online courses requires a lot of self-discipline and accountability. The physical and emotional distance between students and their professors can make it all the easier to skip assignments or not participate in class. They noted:

“It’s all about being on top of your work and holding yourself accountable. If you can handle online college classes, you can handle college.”

“Don’t put off projects and homework just because the deadline isn’t for a little while, you will forget and have to rush to finish it so just do it or start it (and do a good amount of the work) as soon as it is assigned.”

“Study just like you would if you were taking the class in a classroom. No matter where you are learning from, the same level of effort and focus is expected.”

It is challenging to maintain focus on learning online, while also working (or looking for work), raising children and dealing with life’s other responsibilities. One practice that may help students concentrate is to engage in 5-10 minutes of expressive writing before working on school. Ask students to privately jot down everything in their life that is worrying or stressing them out, and write specifically about how each one makes them feel. Rather than suppressing or ignoring their emotions, releasing them on paper lessens their impact and will allow students to better focus on learning or performing. They can even crumple up that piece of paper and toss it in a recycling bin, symbolically discarding those intrusive thoughts so they can get down to business.

Despite our general comfort level with technology, most of us are still unacquainted with experiencing most of our lives online, and things won’t be that much better as we continue remote learning into 2021. While students study algebra, or 20th Century European history or computer coding, remember that they’re still adapting to a whole new way of learning, and that’s not easy. So please pass along advice from our college experts to your students and their instructors so they may be better prepared for any eventual roadblock.

Ross E. O’Hara is director of behavioral science and education at Persistence Plus LLC, which is based in Boston.

Share This Page

Share this...

Filed under College Readiness, Commentary, Demography, Economy, Financing, Journal Type, Schools, Students, Technology, The Journal, Topic, Trends.

Across the U.S., an estimated 60% of incoming community college students require developmental courses to be ready for college-level work, according to estimates by experts. As these courses act as a gateway to further studies, those who fail are most often lost to higher education: Less than a quarter will earn a degree or certificate within eight years.

Connecticut’s Middlesex Community College, an institution serving approximately 3,000 students at locations in Middletown and Meriden, is using new approaches based on behavioral science to improve retention among all students, with a particular focus on students who have historically struggled to earn a degree. In the following Q&A with the New England Board of Higher Education, Jill Frankfort, co-founder of Boston-based Persistence Plus, talks to Adrienne Maslin, dean of students at Middlesex, and Ross O’Hara, behavioral researcher at Persistence Plus, about issues facing community colleges in retaining underprepared college students and the potential offered by interventions that target psychosocial factors related to student success.

What are the challenges facing Middlesex Community College with regard to students being underprepared for college?

Maslin: Our experiences parallel those at other community colleges across the country. At Middlesex, approximately 55% of new students enroll in developmental education courses each year. Of these students, 60% successfully complete those courses, with about 40% moving on to college-level courses within one semester and about 60% within two. Many students, however, are never able to move into college-level courses, with the exception of those courses that do not require college-level reading, writing or math skills. And those are pretty few in number. Of course, the ways in which students are underprepared vary, particularly when you’re talking about the diverse students at a community college. Although our population of traditional, straight-from-high-school students has grown, we have many students who are older and have been away from the learning environment for quite some time. These students tend to have weak math skills and sometimes weak writing skills as well.

Many state legislatures have passed or are considering bills that reform or eliminate developmental education. How has Middlesex responded to legislation passed in Connecticut in 2012 that sought to streamline developmental education?

Maslin: The main objective of the 2012 legislation is to prevent students from languishing in developmental education with no clear path out, which is consistent with the goals of most community colleges, Middlesex included. The challenge, however, which we have begun to remedy, is that students who place into developmental courses frequently need more time on task to master the concepts of the course. To better help these students at Middlesex, we now offer developmental education in a variety of ways for both English and math. First, students can opt to take introductory courses that have developmental education embedded into them.

These students are expected to put more time into the course, but are also provided with the extra assistance necessary to succeed. This allows students to catch-up on key skills while still engaging in college-level work. Second, students can enter into the “Accelerated Learning Program,” which pairs a developmental education and a college-level course. Students take these classes concurrently and earn credit for both, again allowing students to move seamlessly into college-level work while improving in any areas of concern. Finally, students can still enroll in a more traditional developmental education course, as has been the model in the past.

What has Middlesex done to increase retention, particularly among students who historically have low persistence rates, such as those in developmental education courses?

Maslin: Certainly we’re optimistic that offering students more options for transitioning into college-level courses will boost retention among these students. In addition, we now have a full-time retention specialist who’s available to help students with any issues—academic, financial or personal—that may cause them to withdraw. We’ve also put into place a variety of initiatives to support students through the use of technology. One example is our partnership with Persistence Plus—a service that can help support students who may be unable or initially unwilling to take advantage of student services offered in-person.

What is Persistence Plus and how does it work?

O’Hara: Persistence Plus leverages mobile technology to motivate, engage and support more students to degrees. We provide daily, low-touch interventions, known as nudges, to students via their cell phones. These nudges are based on research that tells us that psychosocial factors often play as large a role, if not larger, than academic and financial difficulties in students’ decisions to withdraw from college.

What kinds of psychosocial factors?

O’Hara: Much of this work centers on normalizing the college experience for new students. When many college students struggle, they often assume that everybody else is doing fine and that they simply don’t have what it takes. This attitude tends to be more pervasive among first-generation students and students from low-income backgrounds who have fewer opportunities to discuss college with their families and mentors. Changing these attitudes, therefore, is often the first step to changing students’ performance. For example, students who believe that they can improve their academic abilities, instead of believing that intelligence is set in stone, tend to work harder when struggling and ultimately perform better in college.

Some nudges, therefore, share stories about other students who struggled at first but then did exceptionally well in college. Other nudges let students know that many people go to their professors or the tutoring center for help and that it’s not only normal, but it’s expected of them. Ultimately, we want students to realize that being confused or getting a bad grade is not a sign that they should quit.

Is Persistence Plus the first intervention to target psychosocial factors among college students—or, more specifically, students in developmental education courses?

O’Hara: Certainly not. Many researchers in psychology and education have demonstrated that psychosocial factors can be successfully changed in college students and doing so can lead to better academic outcomes. With regard to developmental education, one of the most noted applications of this research to date is a program called Pathways—two developmental math courses developed by the Carnegie Foundation for the Advancement of Teaching. This program, like Persistence Plus, targets psychosocial factors that can lead students to quit when they don’t understand math, such as the belief that one is simply “not a math person.”

The goal of Pathways is for students to develop strategies for persevering in the face of adversity, a concept they call “productive persistence.” Early results from Pathways were very exciting, with completion rates rising from 6% to 51% in the first year. It’s findings like these that have informed the ways in which Persistence Plus aims to support student success.

What have results been like for students using Persistence Plus at Middlesex?

O’Hara: In fall 2013, we had just over 300 Middlesex students using Persistence Plus. After the first semester, we saw a seven-percentage point higher retention rate among students using Persistence Plus versus those in the general population. We’re particularly excited, though, about our results with developmental education students. Of our cohort of 300 students, approximately 30% were enrolled in at least one developmental education course, and 60% of those students returned to Middlesex for fall 2014, a rate six-percentage points higher than the general population. Also exciting, this advantage in retention was consistent for developmental education students enrolled both full-time and part-time.

How have Middlesex students reacted to the service?

Maslin: Students have had many positive reactions to Persistence Plus. One student commented how “it’s like you can’t really fail” because the nudges help motivate you. Students in developmental education, specifically, have mentioned the sense of community that nudges foster. One student said that nudges were a reminder that they were not “the only one having a crisis in the middle of the semester or worrying about finals.” Another student remarked that “knowing what other students had to say in regards to getting help and reaching out to professors made me want to push harder.”

Nudges, therefore, seem to be effective in normalizing the challenges of college for these students. Also, when we asked another Middlesex student what was most helpful about nudges, they replied “The fact that they were right there on my phone!” It appears then that students enjoy the accessibility of having supportive and personalized messages delivered to them on their cell phones.

What’s next for Middlesex in terms of supporting underprepared students?

Maslin: As we adapt to new models of developmental education, making sure that the students who struggle most are given a chance at success is critical to our mission. With President Obama’s proposal to fund two years of community college, the potential influx of students further underscores the need to find innovative ways to support students with a range of academic and personal backgrounds. Our work with Persistence Plus adds to burgeoning evidence that psychosocial factors play a key role in student success, especially among those underprepared for college and most in need of additional academic support.

We’ve been excited to see that low-touch mobile support is welcomed by students and seems effective at moving the needle on persistence, and we look forward to continuing to support our students to degree achievement in-person, on their phones, and by other means that we haven’t thought of yet.