After seven days as an inpatient for complications related to heart problems, Glenn Shanoski was initially hesitant when doctors suggested in early April that he could cut his hospital stay short and recover at home — with high-tech 24-hour monitoring and daily visits from medical teams.

But Shanoski, a 52-year-old electrician in Salem, Mass., decided to give it a try. He’d felt increasingly lonely in a hospital where the COVID-19 pandemic meant no visitors. Also, Boston’s Tufts Medical Center wanted to free up beds for a possible surge of the coronavirus.

With a push from COVID-19, such “hospital-at-home” programs and other remote technologies — from online visits with doctors to virtual physical therapy to home oxygen monitoring — have been rapidly rolled out and, often, embraced.

As remote visits quickly ramped up, Medicare and many private insurers, which previously had limited telehealth coverage, temporarily relaxed payment rules, allowing what has been an organic experiment to proceed.

“This is a once-in-a-lifetime thing,” said Preeti Raghavan, an associate professor of physical medicine and rehabilitation and neurology at Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine, in Baltimore. “It usually takes a long time — 17 years — for an idea to become accepted and deployed and reimbursed in medical practice.”

Physical therapists traded some hands-on care for video-game-like rehabilitation programs patients can do on home computer screens. And hospitals like Tufts, where Shanoski was a patient, sped up preexisting plans for hospital-at-home initiatives. Doctors and patients were often enthusiastic about the results.

“It’s a great program,” said Shanoski, now fully recovered after 11 days of receiving this care. At home, he could talk with his fiancée “and walk around and be with my dogs.”

But what will remain of these innovations in the post-COVID era is now the million-dollar question. There is a need to assess what is gained — or lost — when a service is delivered remotely. Another variable is whether insurers, which currently reimburse virtual visits at the same rate as if they were in person, will continue to do so. If not, what is a proper amount?

It remains to be seen what types of novel remote care will persist from this born-of-necessity experiment.

Said Glenn Melnick, a health-care economist at the University of Southern California who studies hospital systems: “Pieces of it will, but we have to figure out which ones.”

Hospital At Home

Long established in parts of Australia, England, Italy and Spain, such remote programs for hospital care have not caught on here, in large part because U.S. hospitals make money by filling beds.

Hospital-at-home initiatives are offered to stable patients with common diagnoses — like heart failure, pneumonia and kidney infections — who need hospital services that can now be delivered and managed at a distance.

Patients’ homes are temporarily equipped with the necessities, including monitors and communication equipment as well as backup internet and power sources. Care is overseen by health professionals in remote “command centers.”

Medically Home, the private company providing the service for Tufts, sent its own nurses, paramedics and other employees to handle Shanoski’s daily medical care — such as blood tests or consultations via camera with doctors. They inserted an IV and made sure it was working properly during their visits, which often totaled three a day. Even when Medically Home employees were not there, devices monitored Shanoski’s blood pressure and oxygen levels.

For patients transferred from the hospital, like Shanoski, Tufts pays Medically Home a portion of what the hospital receives in payment. For transfers from an emergency room, Medically Home is paid directly by insurers with which it has contracts.

Before the pandemic, at least 20 U.S. health systems had some form of hospital-at-home setup, said Bruce Leff, a professor at Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine who has studied such programs. He said that, for the right patients, they’re just as safe as in-hospital care and can cost 20% to 30% less.

Tele-Rehab?

Glenn Shanoski, a 52-year-old electrician, spent 11 days with hospital-level care at home —– offered by Tufts Medical Center in Boston. Tufts provides daily visits from medical teams to closely monitor patients in their homes. (Courtesy of Glenn Shanoski)

When the coronavirus shut down elective procedures, many physical-therapy offices had to close, too. But a number of patients who had recently had surgery or injuries were at a crucial point in recovery.

Therapists scrambled to set up video capability, while their trade association called insurers and regulators to convince them that remote physical therapy should be covered.

At the end of April, the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services added remote physical, speech and occupational therapy to the list of medical services it would cover during the pandemic. Just as it had done for other services, the agency said payment would be the same as for an in-person visit.

Though some patient care cannot be done virtually, such as hands-on manipulation of tight muscles, the doctors discovered many advantages: “When you see them in their home, you can see exactly their situation. Rugs lying around on the floor. What hazards are in the environment, what support systems they have,” said Raghavan, the rehabilitation physician at Johns Hopkins. “We can understand their context.”

Using video links, therapists can assess how a patient moves or walks, for example, or demonstrate home exercises. There are also specially designed video-game programs — similar to Nintendo Wii — that utilize motion sensors to help rehabilitation patients improve balance or specific skills.

“Tele-rehab was very much in the research phase and wasn’t deployed on a wide scale,” Raghavan said. Her department now does 9 out of 10 visits remotely, up from zero before March.

Pneumonia Monitoring

Even before the coronavirus emergency, some patients with mild pneumonia were treated as outpatients.

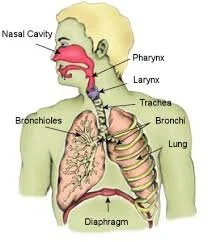

Now, with hospitals busy with COVID-19 cases and patients eager to minimize unneeded exposure, more physicians are considering this option and for sicker patients. The key is using a small device called a pulse oximeter, which clips onto the end of a finger and measures heart rate, while also estimating the proportion of oxygen in the blood. Costing at most a few hundred dollars, and long common in doctors’ offices, clinics and emergency rooms, the tiny machine can be sent home with patients or purchased online.

“We do it on a case-by-case basis,” said Dr. Gary LeRoy, president of the American Academy of Family Physicians. It’s a good option for relatively healthy patients but is not appropriate for those with underlying conditions that could lead them to deteriorate rapidly, such as heart or lung disease or diabetes, he said.

A pulse oximeter reading of 95% to 100% is considered normal. Generally, LeRoy tells patients to call his office if their readings fall below 90%, or if they have symptoms like fever, chills, confusion, increasing cough or fatigue and their levels are in the 91-to-94 range. That could signal a deterioration that requires further assessment and possibly hospitalization.

“Having a personal physician involved in the process is critically important because you need to know the nuances” of the patient’s history, he said.

What It All Looks Like In The Future

Virtual therapy requires patients or their caregivers to accept more responsibility for maintaining the treatment regimen, and also for activities like bathing and taking medicines. In return, patients get the convenience of being at home.

But the biggest wild card in whether current innovations persist may be how generously insurers decide to cover them. If insurers decide to reimburse telehealth at far less than an in-person visit, that “will have a huge impact on continued use,” said Mike Seel, vice president of the consulting firm Freed Associates in California. A related issue is whether insurers will allow patients’ primary caregivers to deliver treatment remotely or require outsourcing to a distant telehealth service, which might leave patients feeling less satisfied.

The industry’s lobbying group, America’s Health Insurance Plans, said the ongoing crisis has shown that telehealth works. But it offered no specifics on future reimbursement, other than encouraging insurers to “closely collaborate” with local care providers.

Whether virtual therapy is cost-effective “remains to be seen,” said USC’s Melnick. And it depends on perspective: It may be cheaper for a hospital to do a virtual physical therapy session, but the patient might not see any savings if insurance doesn’t reduce the out-of-pocket cost.

Julie Appleby is a Kaiser Health News reporter.jappleby@kff.org, @Julie_Appleby