‘The beauty of decay’

“Abundantia’’ (ink jet print), by Tara Sellios, in her show “Ask Now the Beasts,’’ at the Fitchburg (Mass.) Art Museum, through May 24.

The museum says:

“Tara Sellios is a Boston-based artist whose monumental photographs highlight the beauty of the grotesque. Sellios creates still life vignettes from organic materials, including animal bones, insect specimens, and dried flowers which she photographs using a large format 8 X 10 camera. Printed at a large scale, Sellios’s photographs capture the vivid details of her materials. Sellios’s imagery takes inspiration from Christian devotionals including illuminated manuscripts, altarpieces, and stained glass windows while engaging with historical traditions of still life painting, particularly Dutch vanitas paintings. ‘Ask Now the Beasts’ derives its title from the Book of Job, exploring the concepts of the harvest and the apocalypse. In this new work Sellios considers the cyclical nature of Earth, intertwining symbols of death and references to life with the beauty of decay.’’

Llewellyn King: Memories of a ‘91 trip to Venezuela; of course it’s much worse now

Venezuela’s main oil-producing region.

Editor’s note: New England used to heavily depend on oil from Venezuela for heating. Much heating oil for the Northeast now comes from Canada.

WEST WARWICK, R.I.

In 1991, the state oil company of Venezuela, Petroleos de Venezuela, S.A., known as PDVSA, invited the international energy press to visit.

I was one of the reporters who flew to Caracas and later to Lake Maracaibo, the center of oil production, and then to a very fancy party on a sandbar in the Caribbean.

They were, as a British journalist said, “putting on the dog.”

At that time, PDVSA executives were proud of the way they had maintained the standards and practices which had been in force before nationalization in 1976. The oil company was, we were assured, a lean, mean machine, producing about 3.5 million barrels per day.

They were keen to claim they had maintained the same esprit under state ownership as they had had when they were privately owned by American companies.

They had kept political interference at arm's length, executives claimed.

PDVSA's interest then, as it has always been, was more investment, particularly in its natural gas, known as the Cristobal Colon project.

In President Trump's takeover of Venezuela's moribund oil sector, natural gas hasn't been much mentioned — although there may eventually be more demand for natural gas from Venezuela than for its oil.

We had a meeting with Venezuela's president, Carlos Andres Perez, who was called CAP. He painted a rosy future for the country and its oil and gas industry.

CAP believed the oil revenues would modernize the country. Particularly, he said that technology was needed to make the heavy oil more accessible and manageable.

And there's the rub. While everyone is quick to point out that Venezuela's oil reserves are the largest in the world, all oil isn't equal.

Venezuela's oil is difficult to deal with. It doesn't just bubble out of the ground. Instead, 80 percent of it is highly viscous, more like tar than a free-flowing liquid. And it has a high sulfur content.

In other words, it is the oil that most oil companies, unless they have special production and refining facilities, want to avoid. It takes special coaxing to extract the oil from the ground and ship it.

Venezuelan oil has a high “lifting cost” which makes it expensive to begin with. At present, that cost is about $23 per barrel compared to about $13 per barrel for Saudi Arabian oil.

During the energy crisis, which unfolded in the fall of 1973 with the Arab oil embargo, U.S. utilities considered pumping it with a surfactant (a thinner) to Florida and burning it directly in boilers like coal.

As evidence that the oil operation hadn't been damaged by nationalization, executives proudly told us that PDVSA produced more oil with 12,000 employees than the state oil company of Mexico, PEMEX, produced with 200,000.

In other words, the Venezuelans had been able to resist the temptation to turn the oil company into a kind of social- welfare program, employing unneeded droves of people.

Now I read the workforce of PDVSA stands at more than 70,000 and oil production has slipped to about 750,000 barrels a day.

By 1991, the oil shortage which had endured since the Arab oil embargo had eased, and PDVSA was worried about its future and whether its heavy oil could find a wider market.

Particularly, it was worried about the day when it would run out of the lighter crudes and would be left only with its viscous reserves.

Two oil companies have been shipping oil to the United States during the time of revolution and sanctions: Citgo, a PDVSA-owned operator of gas stations in the United States, and Chevron. Both have waivers issued by the United States, although Citgo is under orders to divest and is set to be bought by Elliott Company (owned by Paul Singer, a Trump supporter), which may play a big role going forward in Venezuela as its expertise is in lifting.

About that party on a sandbank. Well, PDVSA wanted to show the press that it could spend money as lavishly as any oil major.

We were flown in a private jet to an island, then transported on speedboats to a sandbank, where a feast worthy of a potentate was set up under tents. The catering staff had been taken off the sandbank, so the effect was that the party had miraculously emerged from the Caribbean Sea.

On X: @llewellynking2

Llewellyn King is executive producer and host of White House Chronicle, on PBS and an international energy-sector consultant. He’s based in Rhode Island.,

Important for Maine and beyond

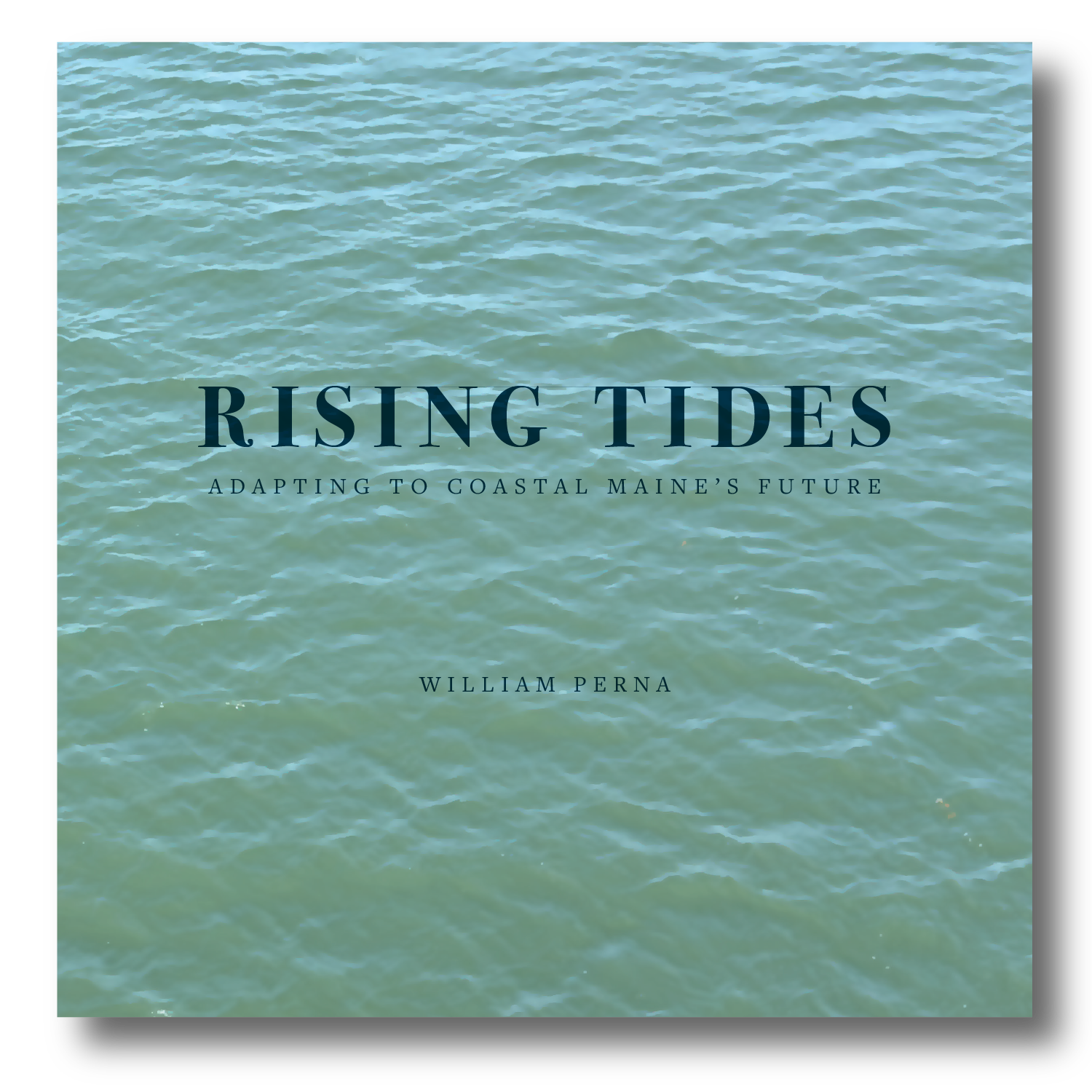

Rising Tides: Adapting to Coastal Maine's Future

$45.00

Hardcover - 10×10

Rising Tides: Adapting to Maine’s Coastal Future captures the memorable voices of Mainers in a rapidly changing world. These include oyster farmers and other aquaculturalists, fishermen, marine biologists and other scientists, and community leaders who are navigating dramatic changes along and off Maine’s iconic coast.

Presenting deep geological, climatological, and human history, in-depth interviews, and other research, the book shows the challenges and opportunities as rising seas caused by global warming, along with sometimes controversial shoreline development, are reshaping ways of life along The Pine Tree State’s storied coast. The vivid changes include shifting fisheries, new industries and markets and the technology that pushes them.

The problems, opportunities, and adaptations in Maine carry lessons for coastal communities around the world. These are global issues described locally through the stories of Mainers on the frontlines. A powerful and timely portrait, Rising Tides is both a warning and an inspiration. It displays the dangers posed by change while also serving as a testament to the ingenuity and determination required not only in Maine but on coasts everywhere.

Dreaming of AI

“A Scholar in His Study (Faust)” (1652) (etching, drypoint and engraving), by Rembrandt van Rijn, in the show “Global Crossings: Selections From the Lunder Collection,’’ at the Colby (College) Museum of Art, Waterville, Maine, Feb. 5-June 7.

Chris Powell: Looking for lessons from happier signs in long-suffering Bridgeport

Skyline of Bridgeport in 2025

— Photo by Quintin Soloviev

MANCHESTER, Conn.

For decades Bridgeport has been Connecticut's worst concentration camp for the poor, easily defeating Hartford, New Haven, and Waterbury for murders, mayhem, wretched poverty, and depravity. State government has taken the city seriously only in regard to the pluralities it produces for Democrats despite its seemingly eternal wretchedness.

But the other week veteran Bridgeport journalist, author and historian, Lennie Grimaldi, broke on his site, OnlyInBridgeport.com, what he fairly suggested could be Connecticut's story of the year, though it is yet to be told elsewhere. That is, Bridgeport, long considered the state's crime capital, having experienced 50 or more murders per year back in the 1990s, had only three in 2025, far below the year's totals in New Haven (16) and Hartford (11). Other major crimes in the city are down too.

Meanwhile Bridgeport's population is rising again and has surpassed 150,000, securing its status as the state's largest city.

Grimaldi speculates that the improvement results in part from federal and local police action against gangs, improvements in housing projects, and more community engagement by the police. One must hope that it's not just a fluke.

Maybe the city's old geographic advantages are reclaiming some appeal too. It has an excellent harbor and is developing a commercial and residential project there. It's on the Metro-North and Amtrak rail line as well as Interstate 95, only slightly less convenient to New York City than prosperous Stamford but more convenient to New Haven's higher-education and medical institutions. The Hartford HealthCare Amphitheater downtown is a regional draw and a soccer stadium may be built. The city has a university and a community college.

But as with Connecticut's other cities, Bridgeport's overwhelming problem remains its demographics, its concentration of poverty, its lack of a large, self-sufficient middle class that can staff a more competent, less selfish municipal government, a government that remains compromised by excessive Democratic patronage and absentee ballot scandals.

And then, of course, there are the thousands of fatherless children in the city's schools, many of them virtually illiterate and demoralized because of neglect at home. State government finally has taken note of the dysfunction of Bridgeport's school system and is intervening somewhat, if not enough. But education will always be mostly a matter of parenting.

While the city's property taxes remain nearly the highest in the state, property taxes are high in all Connecticut's cities, in large part because of state government's refusal to let cities control labor costs and its failure to insist on better results for the huge amount of state funding cities receive.

Mayor Joe Ganim may be doing as well as a mayor in Connecticut can do under urban circumstances. At least he seems to have put his corruption behind him, having been convicted and jailed after his first stint as mayor.

Neither Bridgeport nor Connecticut's other cities can repair themselves on their own. Their futures will be determined mainly by how much the state wants its cities to do more than manufacture poverty while keeping the desperately poor and their pathologies out of the suburbs -- whether the state ever wants to examine and act seriously against the policy causes of poverty, which were operating long before Donald Trump became president.

It should not require a Ph.D. to see that subsidizing childbearing outside marriage with various welfare benefits and then socially promoting fatherless children through school, leaving them uneducated in adulthood and qualified only for menial work, has not led them to self-sufficiency and prosperity but rather to dependence, generational poverty, and mayhem. Only the poverty administrators prosper from such policy.

Indeed, Connecticut seems to think that instead of two parents every child should have a social worker and a probation officer, as well as a "baby bonds" account with the state treasurer's office to ease the burdens to be faced after being raised without two parents.

The “baby bonds" are new but the rest of it is old and just makes poverty worse.

Chris Powell has written about Connecticut government and politics for many years (CPowell@cox.net).

‘The Landscape listens’

January thaw

There's a certain Slant of light,

Winter Afternoons –

That oppresses, like the Heft

Of Cathedral Tunes –

Heavenly Hurt, it gives us –

We can find no scar,

But internal difference –

Where the Meanings, are –

None may teach it – Any –

'Tis the seal Despair –

An imperial affliction

Sent us of the Air –

When it comes, the Landscape listens –

Shadows – hold their breath –

When it goes, 'tis like the Distance

On the look of Death

— Emily Dickinson (1830-1886)

Flexible dress code

Harvard Square, in Cambridge, Mass.

— Photo byWgreaves)

“I especially miss Harvard Square — it’s so unique. Nowhere else in the world will you find a man with a turban wearing a Red Sox jacket and working in a lesbian bookstore. Hey, I’m just glad my dad’s working.’’

— Conan O’Brien (born in 1963 and grew up in Boston area), comedian, TV host and writer.

Battery storage for more energy independence

Everett, looking towards the Mystic Generating Station.

Adapted fromRobert Whitcomb’s “Digital Diary,’’ in GoLocal24.com

As usual, Massachusetts is among those places seeking to strengthen its long-term economy by making itself more self-sufficient in energy. Consider that state officials are entering contract talks with four companies to build a big battery storage facility in Everett on, appropriately, an old Exxon oil-storage field. The facility would be used to store electrical energy when demand is low and release it when it’s high.

New England must move as fast as it can to reduce its energy dependence on the rest of the country and do it in partly by encouraging projects that don’t come under federal/Red State/fossil-fuel sector control – control that opens up the region to economic, political and environmental sabotage by Washington.

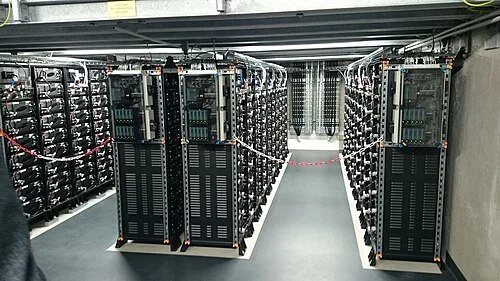

Inside a battery storage power plant at Schwerin,Germany, with modular rows of accumulators.

Paul Bierman: Greenland will be an increasingly dangerous place to exploit resources

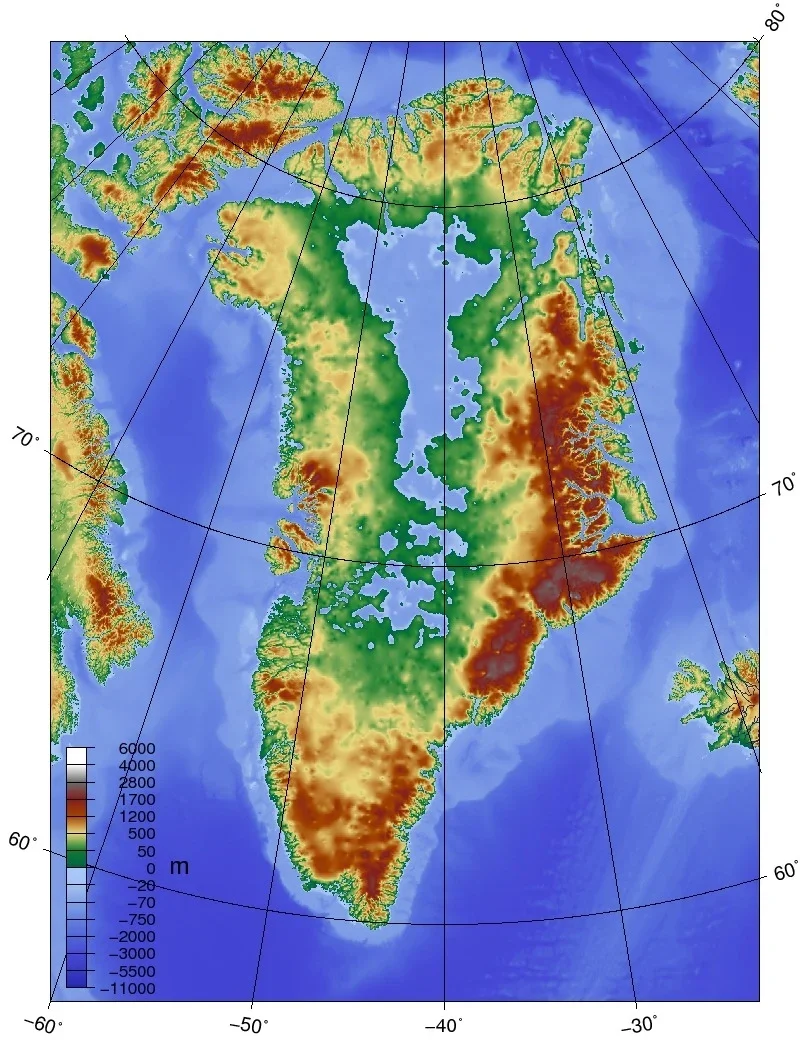

Greenland bedrock is above sea level.

From The Conversation (except the one above).

Paul Bierman is a professor of natural resources and environmental science at the University of Vermont.

He receives funding from the National Science Foundation and the University of Vermont Gund Institute for Environment.

BURLINGTON, Vt.

Since Donald Trump regained the U.S. presidency, he has talked about taking over Greenland. He has insisted that the U.S. will control the island, currently an autonomous territory of Denmark, and that if his overtures are rejected he will perhaps seize Greenland by force. That idea was back in the news again in early 2026 and drawing international condemnation.

When Congress held a hearing on Greenland’s importance to the U.S. in 2025, senators and expert witnesses had focused on the island’s strategic value and its natural resources: critical minerals, fossil fuels and hydropower. No one mentioned the hazards, many of them exacerbated by human-induced climate change, that those longing to possess and develop the island will inevitably encounter.

That’s imprudent, because the Arctic’s climate is changing more rapidly than anywhere on Earth. Such rapid warming further increases the already substantial economic and personal risk for those living, working and extracting resources on Greenland, and for the rest of the planet.

Arctic surface temperatures have been rising faster than the global average. Arctic Report Card, NOAA Climate.gov

I am a geoscientist who studies the environmental history of Greenland and its ice sheet, including natural hazards and climate change. That knowledge is essential for understanding the risks that military and extractive efforts face on Greenland today and in the future.

Greenland: Land of extremes

Greenland is unlike where most people live. The climate is frigid. For much of the year, sea ice clings to the coast, making it inaccessible.

An ice sheet, up to 2 miles thick, covers more than 80% of the island. The population, about 56,000 people, lives along the island’s steep, rocky coastline.

While researching my book When the Ice is Gone, I discovered how Greenland’s harsh climate and vast wilderness stymied past colonial endeavors. During World War II, dozens of U.S. military pilots, disoriented by thick fog and running out of fuel, crashed onto the ice sheet. An iceberg from Greenland sunk the Titanic in 1912, and 46 years later, another sunk a Danish vessel specifically designed to fend off ice, killing all 95 aboard.

Now amplified by climate change, natural hazards make resource extraction and military endeavors in Greenland uncertain, expensive and potentially deadly.

Rock on the move

Greenland’s coastal landscape is prone to rockslides. The hazard arises because the coast is where people live and where rock isn’t hidden under the ice sheet. In some places, that rock contains critical minerals, such as gold, as well as other rare metals used for technology, including for circuit boards and electrical vehicle batteries.

The unstable slopes reflect how the ice sheet eroded the deep fjords when it was larger. Now that the ice has melted, nothing buttresses the near-vertical valley walls, and so, they collapse.

A massive rockslide, triggered by permafrost melt, tumbled down the fjord wall and into the water at Assapaat, West Greenland. Kristian Svennevig/GEUS

In 2017, a northwestern Greenland mountainside fell 3,000 feet into the deep waters of the fjord below. Moments later, the wave that rockfall generated (a tsunami) washed over the nearby villages of Nuugaatsiaq and Illorsuit. The water, laden with icebergs and sea ice, ripped homes from their foundations as people and sled dogs ran for their lives. By the time it was over, four people were dead and both villages lay in ruin.

Steep fjord walls around the island are littered with the scars of past rockslides. The evidence shows that at one point in the last 10,000 years, one of those slides dropped rock sufficient to fill 3.2 million Olympic swimming pools into the water below. In 2023, another rockslide triggered a tsunami that sloshed back and forth for nine days in a Greenland fjord.

A cellphone video captures the June 2017 tsunami wave coming ashore in northwestern Greenland.

There’s no network of paved roads across Greenland. The only feasible way to move heavy equipment, minerals and fossil fuels would be by sea. Docks, mines and buildings within tens of feet of sea level would be vulnerable to rockslide-induced tsunamis.

Melting ice will be deadly and expensive

Human-induced global warming, driven by fossil fuel combustion, speeds the melting of Greenland’s ice. That melting is threatening the island’s infrastructure and the lifestyles of native people, who over millennia have adapted their transportation and food systems to the presence of snow and ice. Record floods, fed by warmth-induced melting of the ice sheet, have recently swept away bridges that stood for half a century.

As the climate warms, permafrost – frozen rock and soil – which underlies the island, thaws. This destabilizes the landscape, weakening steep slopes and damaging critical infrastructure.

An excavator tries to save a bridge over the Watson River at Kangerlussuaq, Greenland. Part of the bridge and the machine were eventually swept away by the rushing meltwater from the Greenland Ice Sheet during a heat wave in July 2012.

Permafrost melt is already threatening the U.S. military base on Greenland. As the ice melts and the ground settles under runways, cracks and craters form – a hazard for airplanes. Buildings tilt as their foundations settle into the softening soil, including critical radar installations that have scanned the skies for missiles and bombers since the 1950s.

Greenland’s icebergs can threaten oil rigs. As the warming climate speeds the flow of Greenland’s glaciers, they calve more icebergs in the ocean. The problem is worse close to Greenland, but some icebergs drift toward Canada, endangering oil rigs there. Ships stand guard, ready to tow threatening icebergs away.

An iceberg passes near an oil drilling rig in eastern Canada. Geoffrey Whiteway/500px Plus via Getty Images

Greenland’s government banned drilling for fossil fuels in 2021 out of concern for the environment. Yet, Trump and his allies remain eager to see exploration resume off the island, despite exceptionally high costs, less than stellar results from initial drilling, and the ever-present risk of icebergs.

As Greenland’s ice melts and water flows into the ocean, sea level changes, but in ways that might not be intuitive. Away from the island, sea level is rising about an inch each six years. But close to the ice sheet, it’s the land that’s rising. Gradually freed of the weight of its ice, the rock beneath Greenland, long depressed by the massive ice sheet, rebounds. That rise is rapid – more than 6 feet per century. Soon, many harbors in Greenland may become too shallow for ship traffic.

Streams of meltwater flow over the silt-covered surface of the Greenland Ice Sheet as it melts in summer heat near Kangerlussuaq in western Greenland. REDA/Universal Images Group via Getty Images

Greenland’s challenging past and future

History clearly shows that many past military and colonial endeavors failed in Greenland because they showed little consideration of the island’s harsh climate and dynamic ice sheet.

Changing climate drove Norse settlers out of Greenland 700 years ago. Explorers trying to cross the ice sheet lost their lives to the cold. American bases built inside the ice sheet, such as Camp Century, were quickly crushed as the encasing snow deformed.

In the past, the American focus in Greenland was on short-term gains with little regard for the future. Abandoned U.S. military bases from World War II, scattered around the island and in need of cleanup, are one example. Forced relocation of Greenlandic Inuit communities during the Cold War is another. I believe that Trump’s demands today for American control of the island to exploit its resources are similarly shortsighted.

Piles of rusting fuel drums sit at an abandoned U.S. base from World War II in Ikateq, in eastern Greenland. Posnov/Moment via Getty Images

However, when it comes to the planet’s livability, I’ve argued that the greatest strategic and economic value of Greenland to the world is not its location or its natural resources, but its ice. That white snow and ice reflect sunlight, keeping Earth cool. And the ice sheet, perched on land, keeps water out of the ocean. As it melts, Greenland’s ice sheet will raise global sea level, up to about 23 feet when all the ice is gone.

Climate-driven sea level rise is already flooding coastal regions around the world, including major economic centers. As that continues, estimates suggest that the damage will total trillions of dollars. Unless Greenland’s ice remains frozen, coastal inundation will force the largest migration that humanity has ever witnessed. Such changes are predicted to destabilize the global economic and strategic world order.

These examples show that disregarding the risks of natural hazards and climate change in Greenland courts disaster, both locally and globally.

This article, originally published Feb. 19, 2025, has been updated with new U.S. attention to Greenland.

‘Like an old Puritan’

Sunrise from the summit of Cadillac Mountain, in Acadia National Park, Maine. It’s known as the first place in the U.S. to see the sunrise, although that is only true for part of the year.

“It’s New England time,

the sun

comes like an old puritan

and it rises over the ocean

and gives leave to the flight of the birds,

it lights a window in Amherst

where the eyes of a woman contemplate the world….’’

— From “The Balada of New England,’’ by Fernando Valverde as translated by Carolyn Forche.

Video: Talking with B.U.’s president

At Boston University: Marsh Plaza and its surrounding buildings, one of the first completed sections of the university’s Charles River campus.

Hear/see this New England Council interview with the president of Boston University.

Llewellyn King: In ‘25 we lost the metaphor of America

WEST WARWICK, R.I.

Come on in, 2026. Welcome. I am glad to see you because your predecessor year was not to my liking.

Yes, I know there is always something going on in the world that we wish were not going on. Paul Harvey, the conservative broadcaster, said, “In times like these, it helps to recall that there have always been times like these.”

Indeed. Wars, uprisings, oppression, cruelty and man's inhumanity to man are to be found in every year. But last year, the world lost something it may not get back. You see, '26 — you don't mind if I shorten your title, do you — we lost America. Not the country but the metaphor.

We were, '26, despite our tragic mistakes — including slavery and wrongheaded wars — a country of caring people, a country that cared (mostly) for its own people and those who lived elsewhere in the world.

It was the country that sought to help itself and to help the world. It was the sharing country, the country that showed the way, the country that sought to correct wrong, to overthrow evil and to excel at global kindness.

It was the country that led by example in freedom of speech, freedom of movement and in free, democratic government.

When John Donne, the English metaphysical poet, described his lover's beauty as ‘‘my America" in the 1590s, he foreshadowed the emergence of the United States a nation of spiritual beauty.

From World War II on, caring was an American inclination as well as a policy.

We helped rebuil Europe with the Marshall Plan, an act of international largesse without historical parallel. We rushed to help after droughts, fires, earthquakes, hurricanes, tsunamis and wars.

We were everywhere with open hands and hearts. America the bountiful. We had the resources and the great heart to do good, to show our own overflowing decency, even if it got mixed up with ideology. We led the world in caring.

We bound up the wounds of the world, as much as we could, whether they were the result of human folly or nature's occasional callousness.

We delivered truth through the Voice of America and aid through the U.S. Agency for International Development. Our might was always at hand to help, to save the drowning, to feed the starving and to minister to the victims of pandemic — as with AIDS and Ebola in Africa.

In 2025, that ended. More than a century of decency suspended, suddenly, thoughtlessly.

America the Great Country became America Just Another Striving Country, decency confused with weakness, indifference with strength, friends with oil autocracies.

It wasn't just the sense of noblesse oblige, which not only distinguished us in the 20th Century, but also earlier. In the 19th Century, we opened our gates to the starving, the downtrodden and the desperate. They joined the people already living here to build the greatest nation — a democracy — that the world has ever seen. First in science. First in business. First in medicine. First in agriculture. First in decency.

These people brought to America labor and know-how across the board, from weaving technology in the 18th century to engineering in the 19th century to musical theater in the 20th century, along with movie-making and rocket science.

I would submit, '26, that it is all about American greatness, and last year we slammed the door shut on greatness, abandoned longtime allies and friends. We forsook people who had been compatriots in war, culture and history for the dubious company of the worst of the worst, aggressors, oppressors, liars, everyone soaked in the blood of their innocent victims.

Yes, '26, America stood tall in the world because it stood for what was right. Its system of law — including the ability to have small wrongs addressed by high courts — was the envy of foreign lands where law was bent to politics, where democracy was an empty phrase for state manipulation of the vote. The Soviet Union claimed democracy; America practiced it.

America soared, for example, with President Jimmy Carter's principled and persuasive pursuit of human rights and President Ronald Reagan's extraordinary explanation of its greatness: the “shining city upon a hill.”

It sunk from time to time. Slavery was horrific; Dred Scott, appalling; Prohibition, silly; the Hollywood blacklist, outrageous.

But '26, decency finally triumphed and America was great, its better instincts superb — and now worth restoring for the nation and for the troubled, brutalized world.

Good luck, '26. You will bear a standard that the world has looked to. Lift it high again.

Llewellyn King is executive producer and host of White House Chronicle, on PBS. Based in Rhode Island, he’s also an international energy-sector consultant and speaker.

On X: @llewellynking2

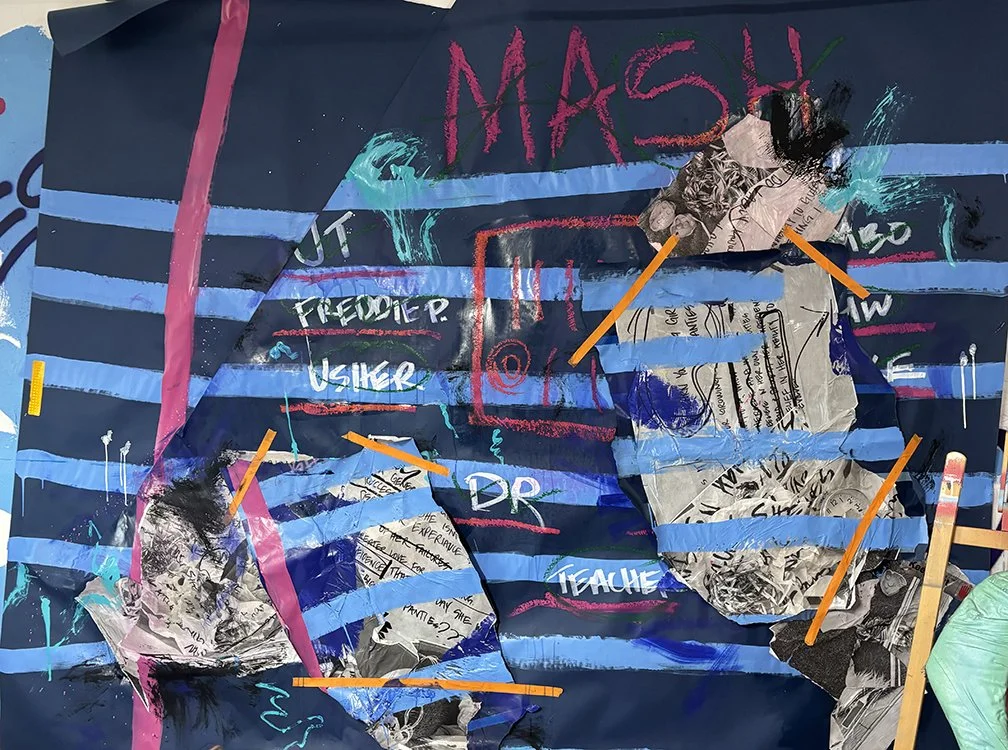

‘Coming-of-age story’

From Moe Gram’s show “Party Fouls,’’ at the Lamont Gallery, Exeter, N.H., through April 11.

The gallery explains:

‘‘‘Party Fouls’ explores the games and pains of growing up. Themes of play, frustration, empathy, and self-compassion interplay through fields of color and found objects. Featured artist Moe Gram transforms Lamont Gallery into a nostalgic birthday party with underlying subjects like maturation, responsibility, and the meandering road of life. The space brims with classic elements of celebration: sugary treats, streamers, Y2K paper games, and even a bouncy house. These playful touches, paired with sculpture, painting, and projection, craft a coming-of-age story that unpacks the trials and tribulations of growing older and losing one’s sense of play.’’

Felicia Nimue Ackerman: Two takes on happiness

The poet’s cat, Winston.

— Photo by Monique Doherty (Photo was misattributed in earlier editions.)

How happy is the little cat

Who thinks my lap is where it's at

And doesn't see what lies beyond

So isn't ready to abscond

Until he glimpses, proud and free,

A bird perched nicely on a tree.

He'd try to catch it, have no doubt,

If I would only let him out.

“Child With Dove” (1901), by Pablo Picasso

How happy is the little child

Whose parents are indeed beguiled

And rush to meet her every need

With unabating love and speed,

Who never has to do a chore,

Or spend her time with any bore,

Whose days are filled with fun and glee --

Oh, how I wish that I were she!

Felicia Nimue Ackerman is a Providence-based poet and a professor of philosophy at Brown University.These poems first appeared in the Emily Dickinson International Society Bulletin.

Before the looters took over

George H.W. Bush (1924-2018) in 1989.

“The government is here to serve, but it cannot replace individual service. And shouldn't all of us who are public servants also set an example of service as private citizens? So, I want to ask all of you, and all the appointees in this administration, to do what so many of you already do: to reach out and lend a hand. Ours should be a nation characterized by conspicuous compassion, generosity that is overflowing and abundant. And you can help make this happen outside of your workplace, in your communities and your neighborhoods, in any of the unlimited opportunities for voluntary service and charity where your help is so greatly needed.’’

—George H.W. Bush, 41st U.S. president, from 1989 to 1993. He was born in Massachusetts and grew up in affluent Greenwich, Conn. These remarks were in a speech to members of the Federal Senior Executive Service on Jan. 26, 1989.

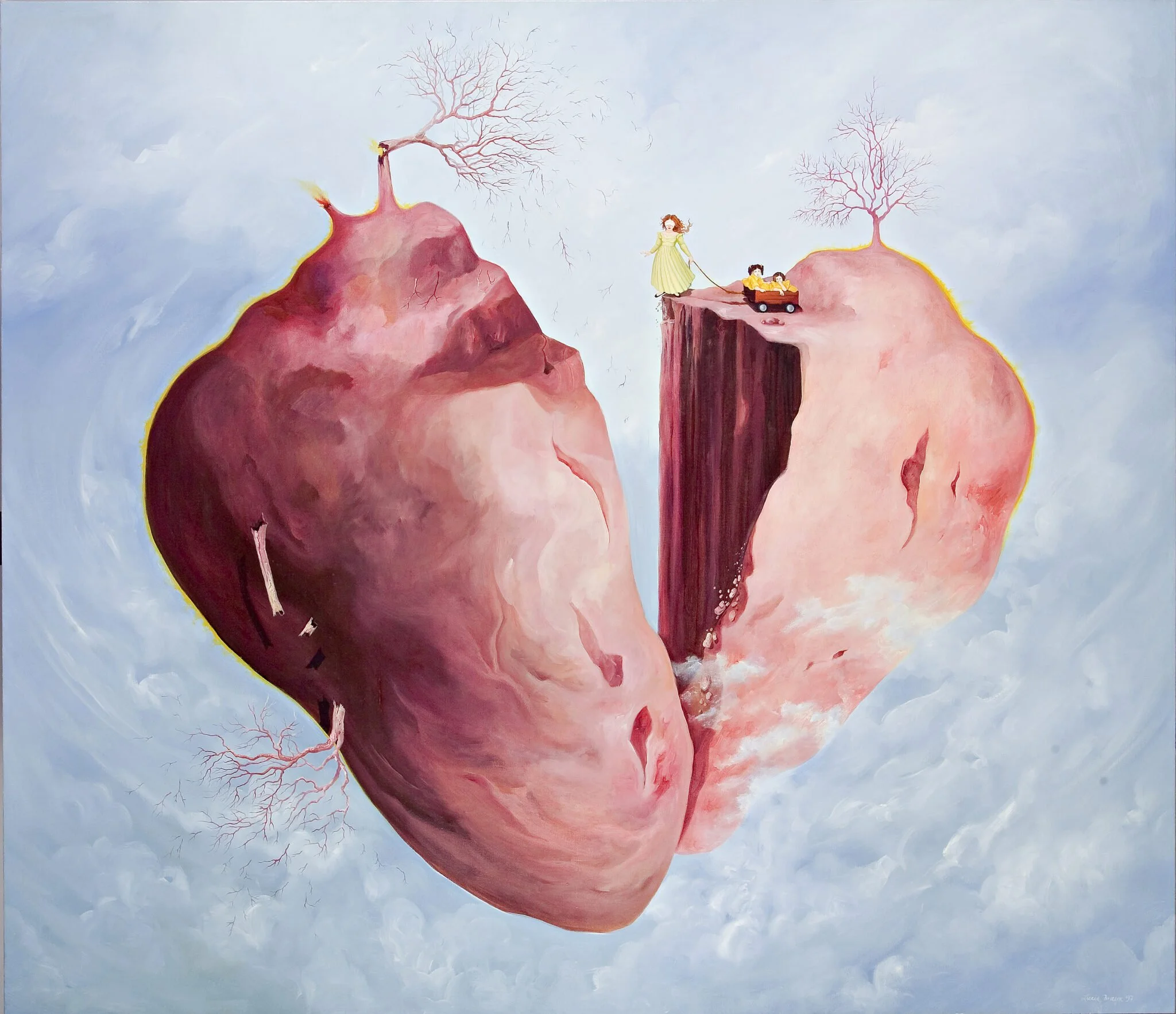

Everything is surreal now

“The Last Heartbeat” (oil on canvas), by Lucia Maya, in the show “Legacies of Surrealism: Works from the Museo de Arte de Ponce,’’ at the Springfield (Mass.) Museums, through Sept. 6.

The museum explains:

“This exhibition, generously loaned from the Museo de Arte de Ponce in Puerto Rico, highlights painters working throughout Latin America and exemplifies the deep influence of Surrealism in the region.

“Although created in the latter half of the 20th Century, these works emphasize thematic and stylistic features that first appeared in the region during the 1930s and developed over the following decades. Through their exploration of the unconscious mind, they give form to dreamlike landscapes, ominous creature-like entities, and strange, non-representational organic shapes that seem inspired by nature.’’

Generously lent by Museo de Arte de Ponce as part of Art Bridges’ Partner Loan Network. Exhibition sponsored locally by Connecticut Public Television.

Outer shape to inner world

“Scenes from a Walk” installation (digital collages of a year of daily walks printed on silk), by Eileen de Rosas, in her show at Boston Sculptors Gallery this April 2-May 3.

She says:

“My work, light and changeable, shifts in space and tone, altering the viewer’s perception of the object and the surrounding space. I use the qualities of light, color, form, and texture to give outer shape to emotions and ideas from my inner world.

‘‘Repetitive physical processes–such as wire crochet, walking, collaging, or casting–ground the work in daily rhythms. Incremental accumulation – of stitches, of photographs, of objects – adds up to a body of work and the days of a life.”

Chris Powell: ‘Gender-affirming care’ is a euphemism

Christine Jorgensen (1926-1989)was an American actress, singer and transgender activist. She was the first person to become widely known in the United States for having sex-reassignment surgery.

MANCHESTER, Conn.

Propaganda is often a matter of names and terminology. For as the Canadian philosopher Marshall McLuhan observed, if you label something well enough, you don't have to argue with it or about it. The label itself may settle the matter politically.

For many years in politically correct places like Connecticut calling people “racist" has been enough to shut most of them up or defeat a proposed course of action. This racket is starting to fail from overuse in part because indignation about supposed racism has failed to lift up the state's minority population, which remains nearly as poor and segregated as ever even as the people who denounce racism have been running the state for decades.

The propagandistic labeling most in use in Connecticut now involves the Trump administration's proposal to forbid hospitals from using federal Medicare and Medicaid money for sex-change therapy for minors.

“This is not medicine," U.S. Health and Human Services Secretary Robert F. Kennedy Jr. says. “It is malpractice. Sex-rejecting procedures rob children of their futures."

Noting that the administration's action is only a proposal, Connecticut Atty. Gen. William Tong replies: “Gender-affirming care remains legal and protected in Connecticut. Donald Trump is not a doctor, and we're not going to let his cruel political agenda dictate access to healthcare or decimate our hospitals. We are exploring all legal options to protect Connecticut families and our medical providers."

Yes, Trump and Kennedy are not doctors. But then neither is Tong, and many doctors agree with Trump and Kennedy. Indeed, medical opinion increasingly holds that most children will get over their gender dysphoria if they are not locked into it by “puberty blockers," hormone injections, and surgeries. Even people who aren't sure about the best response to gender dysphoria may concede that irreversible treatment is best postponed until children can decide as informed adults.

Contrary to the attorney general's suggestion, the Trump administration has not proposed to make gender dysphoria treatment illegal. It has proposed only to prevent life-altering treatments for minors from being federally financed. States could spend their own money on such treatments.

Maybe it will come to that in Connecticut. At least Tong has joined nearly all news organizations in the state in the propaganda war over gender dysphoria. That's what their terminology -- “gender-affirming care" -- is about.

The neutral and accurately descriptive term here is “sex-change therapy." Calling it “gender-affirming care," as the attorney general and the news organizations do, euphemizes it to presume that there is really no controversy at all, nothing to be questioned -- that the desire of minors to change their sex should automatically be “affirmed" with “care."

After all, who could be against “care" except people who, as Tong says, have a “cruel political agenda"? People who disagree with him on this issue couldn't be sincerely concerned about troubled children, could they? They must be drooling MAGA freaks, and maybe racist too -- right?

Or else the attorney general is a demagogue and is being sustained by news organizations that prefer politically correct demagoguery to being fair.

NEW HAVEN'S BRAZEN CONTEMPT: New Haven city government's contempt for the public interest in accountable government has gotten more brazen.

A few weeks ago Mayor Justin Elicker, who is also a member of the city's Board of Education, defended the board's decision not to perform a written evaluation of the school superintendent, only an oral one conducted in secret. The mayor said it wouldn't be productive if city residents knew much about how she was doing.

Now, according to the New Haven Independent, the Elicker administration is mocking the public interest again. It is performing written evaluations of city department heads but only insofar as the evaluations say “satisfactory" or “unsatisfactory." There are no specifics.

Should the department heads improve in some way? The public isn't to know or have any way to judge.

New Haven is proudly the most liberal jurisdiction in the state, and this is what liberalism has come to.

Chris Powell has written about Connecticut government and politics for many years (CPowell@cox.net).