Vox clamantis in deserto

New A.R.T. building nearing completion

Edited from a New England Council report:

Harvard University is nearing completion on the David E. and Stacey L. Goel Center for Creativity & Performance, a 70,000-square-foot facility in Boston’s Allston neighborhood that will be the new home of the American Repertory Theater (A.R.T.). The project, at 175 North Harvard St., topped off its mass-timber structure in October and is expected to open early next year.

The Goel Center will feature two flexible performance venues, a 700-seat West Stage and a 300-seat East Stage, along with rehearsal studios, teaching spaces, a public lobby, and an outdoor performance yard. The building incorporates sustainable design elements, including low-carbon mass timber, reclaimed brick, natural ventilation systems, rooftop solar panels, and a green roof. Catalyzed by a $100 million gift from David E. Goel ’93 and Stacey L. Goel, the center will anchor Harvard’s arts presence in Allston alongside the university’s Science and Engineering Complex and Business School campus.

Inspiration from loneliness

“Shoulder Season” (mixed medium), by Jennifer Goldfinger, in the group show “Polyphony,’’ at Cove Street Arts, Portland, Maine, through April 11.

She says:

“My two forms of creative expression, fine art and children’s books, share themes of isolation, contemplation, empowerment and imagination.

“In the formative years of my middle childhood, my family lived on a farm with neighbors too far apart to know — it was a lonely existence, but in a setting that tickled my imagination. My still resonating emotion from that time unavoidably creeps into my work. As I sift through vintage photographs, I am pulled in by certain expressions on certain children’s faces, and from there the process begins. In working with these characters, I find empathy for them and for my young self. While there is a degree of personal catharsis in this process, I also know there are universal truths here, and perhaps ultimately a greater catharsis as viewers connect with these forgotten souls.

“In my art, the interaction between found antique images and my own photography and encaustic collage work bring forward modern design balanced with nostalgic subject matter. The accessibility and playfulness reflect my work in children’s literature and an imagined context unfolds into a story of the viewer’s own.’’

Give us a break

A depiction of Muhammad receiving his first revelation from the angel Gabriel. From the manuscript Jami' al-tawarikh by Rashid-al-Din Hamadani, 1307, Ilkhanate period.

“Spare us all word of the weapons, their force and range,

The long numbers that rocket the mind;

Our slow, unreckoning hearts will be left behind,

Unable to fear what is too strange.’’

- From “Advice to a Prophet,’’ by Richard Wilbur (1921-2017), famed and mostly New England-based poet

Here’s the whole poem:

Karen Brown: Primary-care practices banding together in western Mass.

Florence, Mass., headquarters of Valley Medical Group

—Photo by John Phelan

Via Kaiser Family Foundation Health News and New England Public Media (not including picture above)

Western Massachusetts, a patchwork of rural communities and low-income cities, is a difficult place to find a primary-care doctor if you don’t already have one. Frustrated patients often turn to online forums, asking for leads or advice on how to find a practice that is accepting new patients.

One name repeatedly crops up in these discussions: Valley Medical Group.

With four locations in the Connecticut River Valley, the practice has been a mainstay of family medicine since the 1990s. Valley Medical’s flagship office, in Florence, can be found right on Main Street, next door to a pizza restaurant and near a Friendly’s.

Valley has 90 medical providers — including doctors, nurse practitioners, and physician assistants — and on-site labs, X-rays, and vision care. With tens of thousands of patients, it’s become one of the largest independent practices in western Massachusetts.

It forms a key part of the region’s health-care infrastructure, yet Valley Medical has rarely been under more strain than it is now. In January, the practice laid off 40 employees — 10% of its 400-person staff — mostly in support positions.

Despite patient demand — there are waiting lists to be seen — primary-care providers take on more clinical responsibilities, and for less pay, than most medical specialists, said the group’s CEO, primary care physician Paul Carlan. Rates are outlined in the group’s contracts with insurance providers.

“It has to do with the fact that our contracts don’t pay as well as we think they should,” Carlan said. “The cost of everything is going up.”

Valley Medical Group is far from alone in this predicament. Thousands of primary-care practices, a key gateway to the medical system, are fighting to remain financially viable — and independent.

In response, many are banding together to form Independent Physician Associations, or IPAs. The goal is to increase their market power, change the way they get paid, and retain control over how they treat patients.

Threats to Physician Autonomy

Primary-practices in the U.S. are in serious trouble, according to workforce surveys. The American Association of Medical Colleges estimates a deficit of up to 86,000 primary-care doctors by 2036, as more primary care doctors retire and fewer enter the field.

The number of people who can’t find a primary-care doctor has grown by 20% in the past decade, according to a recent JAMA Internal Medicine report.

Lower relative salaries and higher professional stress are disincentives when medical students consider a career in primary care. Newly minted doctors can earn more in specialties such as cardiology or surgery.

Financial stresses in U.S. health care, exacerbated by the covid pandemic, have led to the closure of many primary care practices, according to the AAMC.

The Massachusetts Health Policy Commission released a report in 2025 partly blaming the crisis on the relatively low insurance reimbursement rates for primary care. The revenue problem for primary care is projected to get worse when the Republican-backed cuts to Medicaid start to take effect later this year.

As they seek financial security, many primary care practices have merged with large hospital systems, with doctors becoming employees of those systems.

But the doctors at Valley Medical Group were determined to avoid that fate. Joining a health system takes away the autonomy doctors need to make the best clinical decisions for their patients, Carlan said. It also siphons off income into the larger hospital system.

“Our priorities get muddled up,” he said. “And I think when you’re part of a health system, you’re constantly being asked to bend for the needs of the organization. Hospitals get paid when their beds are full.”

By contrast, primary-care providers need time and money to manage or prevent illness, Carlan said, and their insurance reimbursement rates should take that into account.

In December, Valley Medical Group announced it would be joining an Independent Physician Association. Like a union, an IPA combines individual primary-care offices, giving them power in numbers when negotiating contracts with Medicaid, Medicare, and private insurance companies.

“It’s a moment of transition,” said Lisa Bielamowicz, chief clinical officer of TrustWorks Collective, an independent health-care consultancy that works with health systems and physician groups.

IPAs are gaining momentum as older doctors retire, especially following the challenging years of the covid pandemic, Bielamowicz said. “As the Baby Boomers move out and younger physicians take leadership roles, these kinds of models become more attractive.”

The American Academy of Family Physicians, a trade group, is hearing from practice owners who joined hospital systems but now want to break off and return to being a smaller practice.

“So if independent IPAs can create the infrastructure support to make independent practice viable, then that’s a good thing,” said Karen Johnson, a vice president at AAFP.

IPAs can bring more clout to the table when negotiating rates with insurance companies. Some insurers say they like working with these partnerships because they help stabilize primary-care practices, maintaining access and options for insured patients.

Otherwise, some doctors shift their business model to “direct primary care,” which bypasses insurance altogether.

“We’re looking at independent practices that aren’t buoyed by …. these large health systems and can support members in the community in the ways that they want to be supported,” said Lisa Glenn, a vice president with Blue Cross Blue Shield of Massachusetts.

A Different Payment Model

When those independent practices band together, Glenn said, Blue Cross can offer “value-based” contracts. Instead of getting a payment for each visit or procedure, the medical practice is given a budgeted amount for each patient’s care, which provides an incentive to keep them healthy so they need fewer treatments.

Medical providers “make different kinds of choices than they would if they’re paid for every procedure, every visit, every widget,” TrustWorks’ Bielamowicz said.

If there is money left at the end of the year, it’s split between the practice and the insurer.

The catch, Glenn said, is that a value-based contract works only if there’s a big enough pool of patients to spread out the risk, in case a few get really sick. Otherwise, she said, “the risk of ending up above or below the budget becomes somewhat subject to random variation rather than performance.”

Value-based contracts were supposed to be the next big thing when the Affordable Care Act passed in 2010, an innovative way to bring costs down for the health system as a whole.

But they were slow to catch on; the traditional fee-for-service payment model was too entrenched. Experts say that could still change, if enough primary care providers work together to build market power through IPAs.

“If we keep people out of the ER, keep them out of unnecessary hospitalizations, we save money for the system,” said Chris Kryder, CEO of Arches Medical IPA in Cambridge, Mass,, the IPA specializing in value-based contracts that Valley Medical joined. “And we create more income for the PCPs [primary care providers], which is dreadfully needed.”

These contracts also allow more flexibility in staffing, Kryder said, because nurses, physical therapists, and medical assistants can take on some of the less complex medical tasks, saving the practice money.

IPAs Can Help, Depending on Who’s in Charge

But IPAs are not a panacea for primary care’s problems, according to some health-care leaders.

There are hundreds of IPAs, but not all offer the independence and autonomy that many doctors crave. Some IPAs are actually owned by hospital systems, or even private equity companies, and they’re less focused on preventive care.

The American Academy of Family Physicians advises its members to seek out IPAs with “integrity,” ones that give doctors a strong role in decision-making.

“Who’s calling the shots, who’s making the decisions, and is it really focused on the best interests and long-term benefit of physicians in practice and their patients?” asked AAFP’s Johnson.

Arches Medical is owned entirely by physicians and focused specifically on primary care, Kryder said. But to be more effective, Arches needs to recruit more practices that want value-based contracts.

That can be a hard sell, said Glenn, of Blue Cross. Under that payment model, doctors might see a lag of more than a year from the time they provide care to the moment they realize savings.

“It doesn’t happen overnight, and it does take an investment,” she said.

That lag is one reason Valley Medical Group had to lay off staff after joining the Arches IPA, said CEO Carlan. But he has faith that, after some time, the practice will become more financially stable, be able to offer higher salaries, and, most important, keep the doctors in charge.

Karen Brown is a journalist with New England Public Media.

This article is from a partnership that includes New England Public Media and NPR as well as Kaiser Family Foundation Health News.

Roots as metaphors

“Deeply Rooted III (monotype with litho crayon on kitakata paper), by Carol MacDonald, in her show “Roots: Cultivating Connection,’’ at Galatea Fine Art, Boston, through March 29.

The gallery says:

Carol MacDonald says she aims to "address issues of community, life, transition and communication" through her work as a printmaker "tugging at the threads of our shared humanity." This series of monotypes "works with images of roots as a metaphor for the support systems that keep us, as people, anchored and nourished in our seemingly rootless world. Our families, friends, community and service networks combine to sustain us as our lives develop and change.’’

Glass as dialogue

Work by Neil Neil Orange Peel (!) in his show March 18-June 7, at the Cahoon Museum of American Art, Cotuit, Mass.

The museum says:

“The work of Neil Neil Orange Peel is a vibrant reflection of personal evolution, creative exchange, and the transformative power of light. As a dedicated stained glass artist and teacher, he draws inspiration not only from his own journey, but from the hundreds of students who pass through his studio each year, each bringing stories that subtly shape the work.

“Rooted in the rich tradition of stained glass, including the enduring influence of Louis Comfort Tiffany, Neil’s pieces honor historic craftsmanship while embracing a distinctly contemporary voice. Created on Cape Cod, his work is deeply informed by the region’s shifting light, coastal beauty, and vibrant artistic community. The result is stained glass that feels both timeless and personal; an ever-evolving dialogue between place, people, and practice.

Now improved by hedge funder

“Connecticut Farmhouse’’ (medium watercolor on paper), by Warren William Baumgartner (1894-1963), at the New Britain Museum of American Art.

Gerald FitzGerald: ‘Take him to the Truro line’

The original, and long-gone, home of The Provincetown Players, founded in 1915 and the origin of The Provincetown Theater.

In 1966, I won the glamorous position of assistant to Armida Gaeta, the assistant of The New York Times’s foreign-news editor. Armida Gaeta was a tiny woman with enormous spectacles and the demeanor of a ticking bomb.

I was 19 and life was glamorous working exactly one step above office boy.

I had begun working for the paper as a messenger carrying advertising copy and art between agencies and the newspaper in a time long before most computers or even fax machines. My brother proofread classified ads there while attending grad school. I had just flunked out of John Carroll University, in University Heights, Ohio -- news I wouldn't tell my parents until I had a place to stay, a job, and was enrolled in evening classes somewhere.

Helen Durrell was a notable figure in The Times’s personnel operations. She hired me on as a messenger; later I was promoted to office boy. When the newsroom job opened up, she told me that I had to type 60 words per minute even to be interviewed. When I was a kid, Mom had taught me to type by drawing the keyboard of her old Underwood on a shirt cardboard and taping it to the wall in front of me.

“Never look at the keys, just the drawing, and you'll see it forever,” she said.

I thought that I could qualify, so Helen gave me the typing test.

I blew it, finishing at 40 wpm, and then asked when I could take it again. Helen told me I could when I had practiced at home and brought myself up to speed.

“How about tomorrow morning?” I asked.

Helen seemed surprised but didn't say no. That evening, I returned to East 4th St., in Greenwich Village, with beer and cigarettes and checked my typewriter's ribbon to be sure that I wouldn’t discover that I needed a new one after the stores closed. All night long, I sat typing some version of “The quick brown fox jumps over the lazy dog” --- a pangram containing every letter of the alphabet. I hardly ever paused but to sip beer or to use the john. Good thing I could type and smoke simultaneously.

The next day I retook the test and clocked at better than 60 wpm. Aided further by a letter of reference from The Times’s chief legal counsel, James Goodale, secretly orchestrated by his two friendly secretaries, I got the job on the third floor’s huge open newsroom.

For a kid who'd dreamed of news writing since he was old enough to attend movies, I was in heaven. What I mostly did was to compose and distribute a list of the daily whereabouts of each foreign correspondent. My desk was next to those of Seymour Topping, the foreign-news editor, and reporter Harrison Salisbury, just back from duty in Moscow.

The newsroom was an equivalent to square city block, and with few interior walls. It was so big that microphones and loudspeakers were needed to page people to report to the metropolitan desk, the sports desk, the national desk, the foreign desk, obituaries or any other part of the operation. A row of wire-service (Associated Press, UPI, Reuters, Agence France-Presse, etc.) teletype machines, constantly sounding bells and keystrokes, stood one after another after another from West 43rd St. to West 44th St.

xxx

Only my then-19-year-old mind could possibly explain why I carried just $5 for a week's stay in Provincetown, Mass. But at least I already had my ticket to Eugene O'Neill's A Moon for the Misbegotten, at the famous Provincetown Theater, along the beach. The theater’s origins go back to 1915, with the establishment of the Provincetown Players.

My tall, blond buddy, Dennis Niermann, nicknamed “The Swede” and from Ohio, would hitch with me as far as Boston. He'd been visiting my fifth-floor walk-up single-bedroom apartment at 73 East 4th St., between Second Avenue and Bowery. I had taken it over from my brother and usually had two roommates to split the $85-a-month rent three ways.

Taking the long route home to Cleveland, Dennis was doing me a favor, but he wouldn't have minded the company, either. At the time he may have been reading electricity meters for a living but, just so you know, he later became a renowned anti-discrimination lawyer. We got to Boston easily and early. We probably grabbed a burger at the Paramount, a Greek place on Charles Street, but eventually walked over to Boston Common, where we rolled out our sleeping bags in the dusk atop a grassy hill just beneath the looming column of the Soldiers and Sailors Monument and slept on the ground undisturbed through the night. You could do that back then. After coffee somewhere, Dennis and I split, he hoofing over to the Mass Pike West and I to hitchhike on Route 3 South, toward Cape Cod.

I don't remember how many rides it took to reach Hyannis, the biggest town center on The Cape, but I recall that it was getting dark and starting to rain as I walked up Main Street in search of somewhere dry. I had visited Hyannis years earlier, when New York neighbor Jack McCarthy took me deep-sea fishing with his son, Johnny. Mr. McCarthy won the boat pool for most fish; Johnny won for biggest, and I won for the first fish caught.

This time I walked past the miniature golf course, where we'd played to celebrate. Just down a cross street, I found a wooden three-sided shelter with a bench and roof. It must have been provided for those waiting for a bus or train. I snuggled into one corner and began to assess my chances of spending the night there without getting rousted by an overeager patrolman. My hand brushed something I could not see in the dark shelter.

It turned out to be one of those small leather change purses. I snapped it open. Inside were two fives and two singles and some quarters, dimes and nickels. No I.D. No phone number. Not even a scrawled nickname. My personal wealth had just catapulted from maybe two bucks to almost fifteen.

I remembered a sign for a really cheap-looking lodging back along Main Street, not a far walk from the miniature golf course on the same side of the street. I found it and purportedly clean sheets for something like $3 a night. I am sure that its exterior sign used the word “Hotel,” but, make no mistake, it was a flop house. The room was the size of an elevator, and none of its walls reached the ceiling. A flop house in Hyannis seems somehow strange, but there it was, and it was dry and I took it.

The next day, I found Route 6 North and, eventually, Provincetown, and walked to the playhouse. I had no plan other than to redeem my ticket, but that would not be for a night or so.

I know that somewhere I still have the playbill from the small wooden theater that burned down about a decade later, but as I write I cannot put hands on it.

I know I have it because I never once in my life have discarded a playbill. I always kept them, and if years later I attended a show with my wife and/or my kids, they signed my playbill. I am going to have to inspect our attic closely. In my dad's Empire book case I have all the playbills from the last nearly 50 years we have lived in our present home. The earlier ones must be boxed somewhere in the attic.

My memory of the small wooden theater along Cape Cod Bay might be distorted.

I spent the week sleeping beneath an overturned dory on a tiny strip of beach that I recall as being between the playhouse and Bradford Street. But that's crazy. The beach must have been on the harbor side of the theater. There were wooden benches inside and space to seat fewer than 200. The theater was made of wooden planks and was caressed by a salty breeze. I don't think that it was insulated at all.

Carved upside down in the port side of the bow of the wooden-plank dory were these words: “The Baron's crib.” I took this to mean that a former adventurer had escaped the elements and, possibly, the nosy, while resting concealed and dry beneath the overturned boat. So that is what I immediately decided to do.

In Provincetown I enjoyed the O'Neill play, whose lead character, Jamie Tyrone, was based on the author's ne'er-do-well older brother in a kind of expansion of the playwright's Long Day's Journey Into Night. My days were spent lazing on the beach reading while eating bread and bologna or occasionally walking through town. I was warm, dry and comfortable within The Baron's crib. Until my very last night.

In the morning blackness, at about 2 or 3 a.m., glaring light burned my face closely, held like a weapon by a uniformed police officer lifting the dory while growling about impermissibly sleeping on the beach. He ordered me to accompany him to Town Hall, a few blocks away. I don't recall that he handcuffed me. We walked to the closed building and, somewhere on the side toward its left rear entered a jail. There was one cell, two at most. A man occupied the only cot in the cell, where they placed me so that if there really were two I think I would have asked for the empty other. Anyway, the man rose as I entered. He reeked of a superhuman dose of cologne. Truly fetid.

It now being surely around 3 a.m. I asked the guy when he'd been arrested. After 10 p.m., he guessed.

“So you've had five hours on the cot,” I told him. “I guess it’s my turn.”

I stretched out on the rumpled, sickly-sweet smelling sheet and was glad to have it. I've always been able to sleep pretty much anywhere, but this was genuinely difficult. My roommate meanwhile sat on the floor, his back against the bars.

I do not recall being offered anything to eat or drink in the morning, and I think we may have been cuffed to go upstairs to the large room being used for court. I was callow enough to be mostly concerned that observers might consider me to be “with” my cellmate, whose offense I never did learn.

When my name was called, I stood before the black-robed judge sitting above the rest of us. He told me that sleeping on the beach carried a $25 fine and asked me if I had anything to say?

I looked up at him and said, quietly:

“Your honor, if I had 25 bucks I wouldn't've been sleeping on the beach.”

The judge looked at me and then turned, a bit harshly, toward a uniformed cop standing off to the side of his bench.

“Take him to the Truro line!” snapped his honor. (Truro being the next town south.)

My response to the judge was the first of hundreds, if not thousands, of responses to judges following a series of news jobs and what became close to 40 years of addressing courts as a trial lawyer. Never having paid a dime in penalty for sleeping on the beach, I guess it counts as a win.

Gerald FitzGerald’s career has included being a newspaper editor, a writer, a prosecutor, a defense lawyer and a civic leader. He lives on Massachusetts’s South Coast.

But I want to drink alone

Oil painting by Keith Thomson, at Renjeau Galleries, Natick, Mass.

The gallery says:

“Keith Thomson’s vibrant artwork showcases a masterful grasp of perspective, surrealism, and humor. He playfully juxtaposes quotidian, every-day scenery with elements of wit and satire, an homage to his career as a political cartoonist in the ‘90s. Thomson’s art is rendered via digital sketch, then transferred on to canvas and layered with oil paint for shading and added dimension.’’

What it means to remember

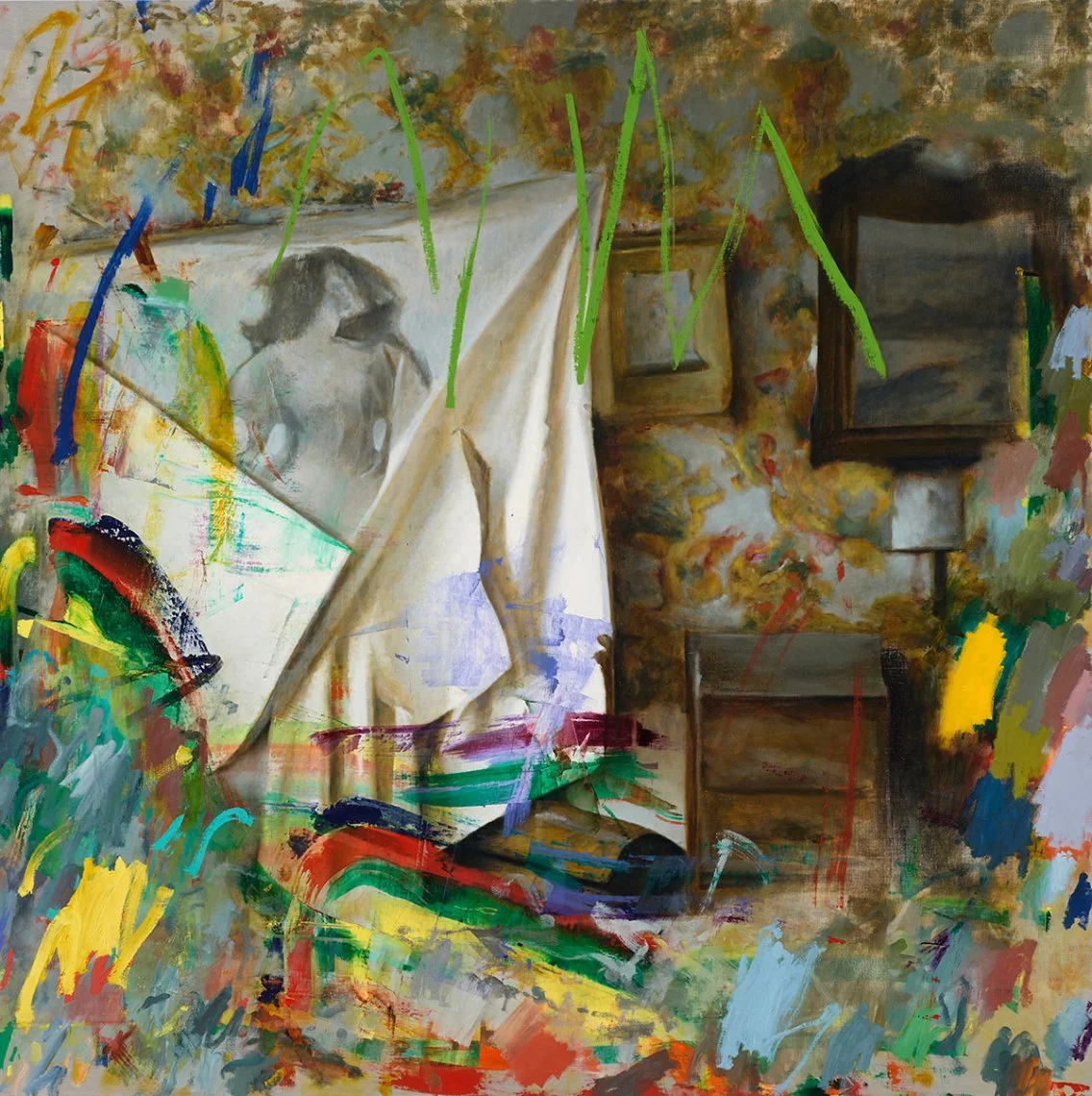

“Collaboration 35 (Angel 1)” (oil on linen), by Damian Stamer, in his show “Angels & Ghosts,” at the Middlebury College Museum of Art, in Middlebury, Vt. He calls it part of his “photographic childhood memory exploring the bedroom of an abandoned rural North Carolina house filled with old junk. Hoarder, floor to ceiling. Mildewed sheets, stained blankets, strong tonal shifts. Old painting hanging on the wall.’’

The museum says:

“Born in 1982 in Durham, North Carolina, where he continues to live and work, Damian Stamer explores the intricacies of time, memory, and existence through his paintings. His work addresses fundamental questions about what it means to remember, create, and be human, offering reflections on our relationship with technology and its impact on our perception of self and the world.’’

Ski trip with Undertones

Cannon Mountain Ski Area and Echo Lake seen from Artist's Bluff.

Photo by David W. Brooks

Adapted from Robert Whitcomb’s “Digital Diary,’’ in GoLocal24.com

This time of year reminds me of spring skiing in Vermont and New Hampshire, bouncing down the mountain on that melting granular stuff, called “corn snow,’’ in the warming sunshine.

Back around 1957 I joined several of the kids of a large family and their very vivacious and seemingly very married mother on a trip to Cannon Mountain (home of such wonderfully named trails as “Polly’s Folly”) and the broader northern New Hampshire/Vermont area. When we got up there, a dashing man in an MG joined our group. While he was very nice to all, I sensed something, er special, was going on between him and the mother.

The mother eventually got divorced and married this rich, apparently charming, and handsome, man; her previous husband was merely rich. But this marriage didn’t last either. I visited her many years later, when she was running an inn she had converted from a mansion near the village center of a beautiful and affluent New England town, apparently with the help of a boyfriend she was living with. She was mellow, still very funny and, in a way, sexy.

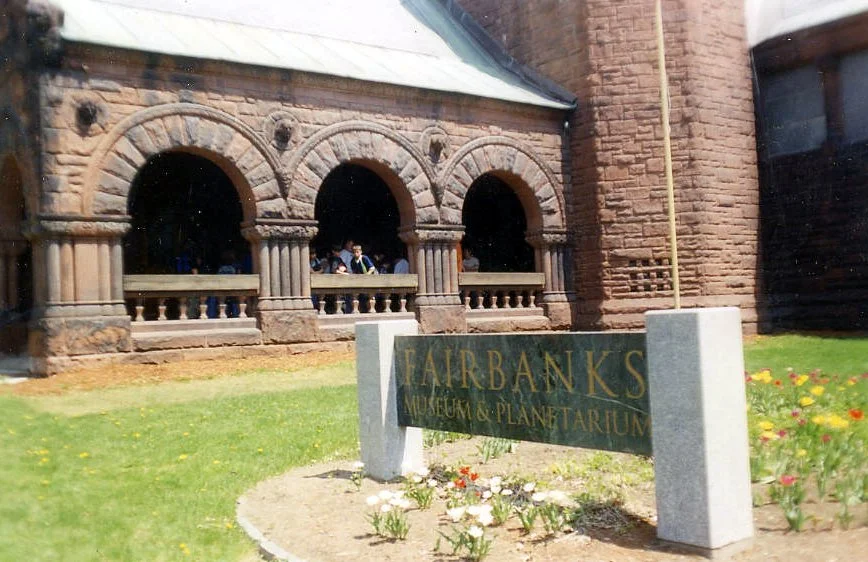

Another highlight of the trip was our tour of what seemed to be the world’s maple syrup and maple candy manufacturing capital – St. Johnsbury, Vt. -- during the height of sap season. Rich aromas! (Visit the wonderful Fairbanks Museum in that town:

But my sharpest memory is how we were accompanied by that mysterious man. I thought of it many years later when reading L.P. Hartley’s novel The Go-Between, with its haunting opening: "The past is a foreign country: they do things differently there.’’ Or is it more William Faulkner’s line “The past is never dead. It’s not even past,” from his novel Requiem for a Nun.

The wonderful Fairbanks Museum, in St. Johnsbury, Vt.

A use of adversity

Nineteenth century depiction of Anne Bradstreet by Edmund H. Garrett. No portrait made during her lifetime exists

“If we had no winter, the spring would not be so pleasant: if we did not sometimes taste of adversity, prosperity would not be so welcome."

— From Anne Bradstreet’s (1612-1672) “Meditations Divine and Moral." The Massachusetts Bay Colony Puritan was the first major poetic voice in British colonial America.

rodenticides imperil a wide range of wildlife

Barred Owl

—Photo by Mdf

Excerpted from an article by Rob Smith in ecoRI News

PROVIDENCE — Earlier this year, the head of Brown University’s bird-watching club called Sheida Soleimani.

The student had found a barred owl, usually a nocturnal creature, in the middle of the day, sitting on the pavement near the Faculty Club on Bannister Street. Next to the owl, said Soleimani, was a rodenticide box, filled with anticoagulant poison designed to kill rats and mice.

Soleimani is one of the state’s few wildlife rehabilitators, and the only one that focuses mainly on Rhode Island’s bird population. For the state’s bird-lovers, when they find a sick or dying bird, Soleimani is the 911 call.

When she picked up the barred owl, it was limp and trembling. Its eyes were half open, its entire body bruised, and blood was dripping from its beak. The owl died within hours, another casualty of an accidental poison in its food supply.

‘the power of Pattern’

Left, “Tulips Pop Up in the Forest” (mosaic) by Lisa Houck, and right, “Solar Spin” (encaustic) by Ross Ozer, in their joint show “Patterned Worlds,’’ at Concord (Mass.) Art, April 2-May 3.

The gallery says:

“The works of Lisa Houck and Ross Ozer meet through a shared commitment to color, pattern, and the handmade.

“Houck’s mosaics evoke living landscapes—birds, leaves, pods, and currents built from thousands of tesserae that shift subtly in hue and rhythm. Her compositions reflect the organic logic of nature: flowing, intertwining, and filled with movement.

“Ozer’s geometric encaustic paintings offer a structured counterpoint. Created dot-by-dot in wax, his works explore circles, arcs, grids, and nested forms inspired by quilting traditions and Bauhaus design. Each composition uses repetition and precise color harmonies to create a sense of balance and architectural clarity.

“Presented together, these two bodies of work reveal parallel ways of constructing visual coherence from tiny incremental units. One is organic, one geometric; one narrative, one abstract. Their dialogue celebrates the beauty of craft, the power of pattern, and the expressive possibilities of color.’’

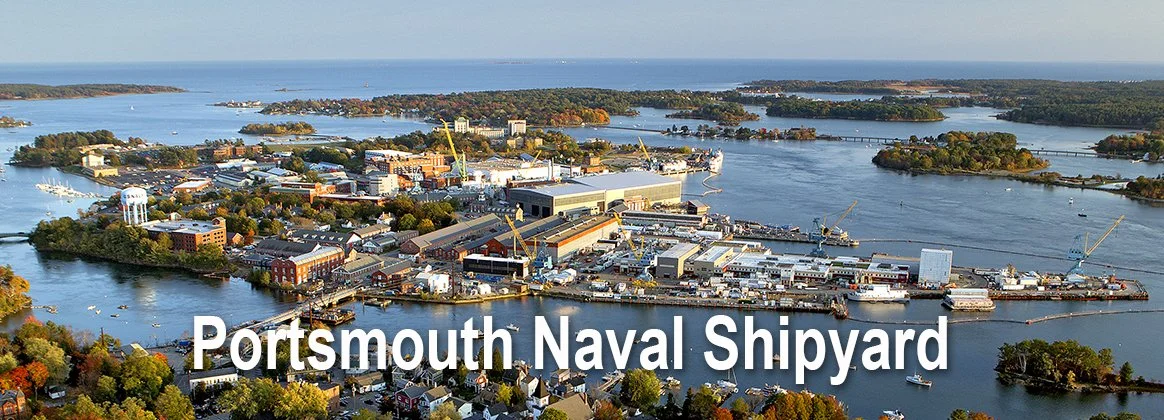

Do it in the open

The famous shipyard is on Seavey Island, in Kittery, Maine, adjacent to Portsmouth, N.H.

“All officers of the Intelligence Community, and especially its most senior officers, must conduct themselves in a manner that earns and retains the public trust. The American people are uncomfortable with government activities that do not take place in the open, subject to public scrutiny and review.’’

Dennis C. Blair (born 1947 in Kittery, Maine, and son of a Navy captain) was director of national intelligence under President Obama.

Carolina Rossini: Why lawsuit involving Instagram is so important

From The Conversation (not including image above.)

Carolina Rossini is a professor of practice and director of the Public Interest Technology Initiative at the University of Massachusetts at Amherst.

She was a staffer at organizations including the Electronic Frontier Foundation, Public Knowledge, and the Harvard Berkman Klein Center, which were funded by various foundations and companies. See https://www.carolinarossini.net/bio

A Los Angeles courtroom is hosting what may become the most consequential legal challenge Big Tech has ever faced.

This is an inflection point in the global debate over Big Tech liability: For the first time, an American jury is being asked to decide whether platform design itself can give rise to product liability – not because of what users post on them, but because of how they were built.

As a technology policy and law scholar, I believe that the decision, whatever the outcome, will likely generate a powerful domino effect in the United States and across jurisdictions worldwide.

The case

The plaintiff is a 20-year-old California woman identified by her initials, K.G.M. She said she began using YouTube around age 6 and created an Instagram account at age 9. Her lawsuit and testimony allege that the platforms’ design features, which include likes, algorithmic recommendation engines, infinite scroll, autoplay and deliberately unpredictable rewards, got her addicted. The suit alleges that her addiction fueled depression, anxiety, body dysmorphia – when someone see themselves as ugly or disfigured when they aren’t – and suicidal thoughts.

TikTok and Snapchat settled with K.G.M. before trial for undisclosed sums, leaving Meta and Google as the remaining defendants. Meta CEO Mark Zuckerberg testified before the jury on Feb. 18, 2026.

Meta CEO Mark Zuckerberg testified in court in a lawsuit alleging that Instagram is addictive by design.

The stakes extend far beyond one plaintiff. K.G.M.’s case is a bellwether trial, meaning the court chose it as a representative test case to help determine verdicts across all connected cases. Those cases involve approximately 1,600 plaintiffs, including more than 350 families and over 250 school districts. Their claims have been consolidated in a California Judicial Council Coordination Proceeding, No. 5255.

The California proceeding shares legal teams and evidence pool, including internal Meta documents, with a federal multidistrict litigation that is scheduled to advance in court later this year, bringing together thousands of federal lawsuits.

Legal innovation: Design as defect

For decades, Section 230 of the Communications Decency Act shielded technology companies from liability for content that their users post. Whenever people sued over harms linked to social media, companies invoked Section 230, and the cases typically died early.

The K.G.M. litigation uses a different legal strategy: negligence-based product liability. The plaintiffs argue that the harm arises not from third-party content but from the platforms’ own engineering and design decisions, the “informational architecture” and features that shape users’ experience of content. Infinite scrolling, autoplay, notifications calibrated to heighten anxiety and variable-reward systems operate on the same behavioral principles as slot machines.

These are conscious product design choices, and the plaintiffs contend they should be subject to the same safety obligations as any other manufactured product, thereby holding their makers accountable for negligence, strict liability or breach of warranty of fitness.

Judge Carolyn Kuhl of the California Superior Court agreed that these claims warranted a jury trial. In her Nov. 5, 2025, ruling denying Meta’s motion for summary judgment, she distinguished between features related to content publishing, which Section 230 might protect, and features like notification timing, engagement loops and the absence of meaningful parental controls, which it might not.

Here, Kuhl established that the conduct-versus-content distinction – treating algorithmic design choices as the company’s own conduct rather than as the protected publication of third-party speech – was a viable legal theory for a jury to evaluate. This fine-grained approach, evaluating each design feature individually and recognizing the increased complexities of technology products’ design, represents a potential road map for courts nationwide

.

What the companies knew

The product liability theory depends partly on what companies knew about the risks of their designs. The 2021 leak of internal Meta documents, widely known as the “Facebook Papers,” revealed that the company’s own researchers had flagged concerns about Instagram’s effects on adolescent body image and mental health.

Internal communications disclosed in the K.G.M. proceedings have included exchanges among Meta employees comparing the platform’s effects to pushing drugs and gambling. Whether this internal awareness constitutes the kind of corporate knowledge that supports liability is a central factual question for the jury to decide.

Tobacco companies were eventually held to account because what they knew – and hid – about the addictiveness of their products came to light. Ray Lustig/The Washington Post via Getty Images

There is a clear analogy to tobacco litigation. In the 1990s, plaintiffs succeeded against tobacco companies by proving they had concealed evidence about the addictive and deadly nature of their products. In K.G.M., the plaintiffs here are making the same core argument: Where there is corporate knowledge, deliberate targeting and public denial, liability follows.

K.G.M.’s lead trial attorney, Mark Lanier, is the same lawyer who won multibillion-dollar verdicts in the Johnson & Johnson baby powder litigation, signaling the scale of accountability they are pursuing.

The science: Contested but consequential

The scientific evidence on social media and youth mental health is real but genuinely complex. The Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-5) does not classify social media use as an addictive disorder. Researchers like Amy Orben have found that large-scale studies show small average associations between social media use and reduced well-being.

Yet Orben herself has cautioned that these averages might mask severe harms experienced by a subset of vulnerable young users, particularly girls ages 12 to 15. The legal question under the negligence theory is not whether social media harms everyone equally, but whether platform designers had an obligation to account for foreseeable interactions between their design features and the vulnerabilities of developing minds, especially when internal evidence suggested they were aware of the risks.

First, a manufacturer has a duty to exercise reasonable care in designing its product, and that duty extends to harms that are reasonably foreseeable. Second, the plaintiff must show that the type of injury suffered was a foreseeable consequence of the design choice. The manufacturer doesn’t need to have foreseen the exact injury to the exact plaintiff, but the general category of harm must have been within the range of what a reasonable designer would anticipate.

This is why the Facebook Papers and internal Meta research are so legally significant in K.G.M.’s case: They go directly to establishing that the company’s own researchers identified the specific categories of harm – depression, body dysmorphia, compulsive use patterns among adolescent girls – that the plaintiff alleges she suffered. If the company’s own data flagged these risks and leadership continued on the same design trajectory, that would considerably strengthen the foreseeability element.

Why it matters

Even if the science is unsettled, the legal and policy landscape is shifting fast. In 2025 alone, 20 states in the U.S. enacted new laws governing children’s social media use. And this wave is not only in the U.S.; countries such as the U.K., Australia, Denmark, France and Brazil are also moving forward with specific legislation, including mandates banning social media for those under 16.

The K.G.M. trial represents something more fundamental: the proposition that algorithmic design decisions are product decisions, carrying real obligations of safety and accountability. If this framework takes hold, every platform will need to reconsider not just what content appears, but why and how it is delivered.

Getting to know you

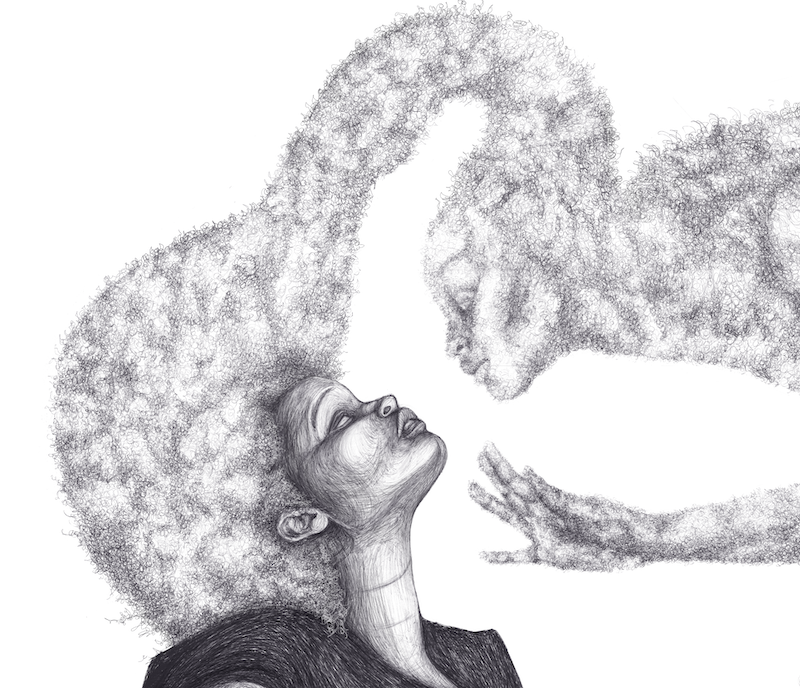

Work by Samantha Modder in her show “Of All the Worlds We Could Have Dreamed,’’ at 3SArtspace, Portsmouth, N.H., April 3-May 31.

The gallery says:

“Samantha Modder's work feels like stepping into a fairytale drawn in ballpoint pen and then blown up to the scale of a building. The artist creates large-scale, digitally manipulated drawings printed on adhesive paper — murals that reshape the entire space.

“‘Of All the Worlds We Could Have Dreamed’ follows a single Black woman and her alter-egos moving through a world built entirely from her imagination. It’s part storybook, part dreamscape, and part test lab — a place where she explores power, resistance, rest, and the realities Black women navigate every day. Black hair becomes a protagonist here, driving the narrative in curls, coils, and shapes that feel both soft and defiant.’’