Providence’s College Hill on a beautiful fall day

Results of a stroll by New England Diary on Oct. 14

Finally out of the house

“September smiled at her wonderful friends in all their colors and bright eyes and gentle ways. “You know, in Fairyland-Above they said that the underworld was full of devils and dragons. But it isn’t so at all! Folk are just folk, wherever you go, and it’s only a nasty sort of person who thinks a body’s a devil just because they come from another country and have different notions.”

― Catherynne M. Valente

Photo by Fiona Gerety, Wickenden Street, Providence, RI.

September 13, 2020

On Sunday, Sept. 15: People enjoying themselves at the annual Bristol PorchFest

Video by Lydia Davison Whitcomb

David Warsh: 35 years of chronicling complexity

SOMERVILLE, Mass.

In the summer of 1984, starting out as an economic journalist for The Boston Globe, I published The Idea of Economic Complexity (Viking). “Complexity,” I wrote, “is an idea on the tip of the modern tongue.”

About that much, at least, I was right.

My book was received with newspaperly courtesy by The New York Times, but it was soon eclipsed by three much more successful titles. Chaos: The Making of a New Science (Viking), by James Gleick, appeared in 1987. Complexity: The Emerging Science at the Edge of Order and Chaos (Simon & Schuster), by M. Mitchell Waldrop, and Complexity: Life at the Edge of Chaos (Macmillan), by Roger Lewin, both appeared in 1992. The reviewer for Science remarked that the latter read like the movie version of the former.

Gleick reported on the doings of a community of physicists, biologists and astronomers, including mathematician Benoit Mandelbrot, who were studying, among other things, “the butterfly effect.” Lewin and Waldrop both wrote mainly about W. Brian Arthur, of the Santa Fe Institute. I had pinned my hopes on Peter Albin, of the City University of New York, whose students hoped he would be the next Joseph Schumpeter.

When the famously pessimistic financial economist Hyman Minsky retired, Albin was chosen to replace him at the Levy Institute at Bard College, but he suffered a massive stroke before he could take the job. Duncan Foley, then of Barnard College, edited and introduced a volume of Albin’s papers: Barriers and Bounds to Rationality: Essays on Economic Complexity and Dynamics in Interactive Systems (Princeton, 1998). Arthur went on to win many awards and write a well-regarded book, The Nature of Technology: What It Is and How It Evolves (Free Press, 2011).

By then complexity had become a small industry, powered by a vigorous technology of agent-based modeling. Publisher John Wiley & Sons started a journal, Princeton University Press a series of titles, Ernst & Young opened a practice. Among the barons who came across my screen were John Holland, Scott Page, Robert Axelrod, Leigh Tesfatsion, Seth Lloyd, Alan Kirman, Blake LeBaron, J. Barkley Rosser Jr., and Eric Beinhocker, as well as three men who became good friends: Joel Moses, Yannis Ionnides, and David Colander. All extraordinary thinkers. I long ago went far off the chase.

Two of the most successful expositors of economic complexity were research partners, as least for a time: Ricardo Hausmann, of Harvard University’s Kennedy School of Government, and physicist César Hidalgo, of MIT’s Media Lab. They, too, worked with a gifted mathematician, Albert-László Barabási, of Northeastern University, to produce a highly technical paper; then, with colleagues, assembled an Atlas of Complexity: Mapping Paths to Prosperity (MIT, 2011), a data-visualization tool that continues to function online. Meanwhile, Hidalgo’s Why Information Grows: The Evolution of Order, from Atoms to Economies (Basic, 2015) remains an especially lucid account of humankind’s escape (so far) from the Second Law of Thermodynamics, but there is precious little economics in it. For the economics of international trade, see Gene Grossman and Elhanan Helpman.

That leaves economist Martin Shubik, surely the second most powerful mind among economists to have tackled the complexity problem (John von Neumann was first). Shubik pursued an overarching theory of money all his life, one in which money and financial institutions emerge naturally, instead of being given. In The Guidance of an Enterprise Economy (MIT, 2016), he considered that he and physicist Etic Smith had achieved it. Shubik died last year, at 92. His ideas about strict definitions of “minimal complexity” will take years to resurface in others’ hands.\

So what have I learned? That the word itself was clearly shorthand: complexity of what? One possible phenomenon is complexity of the division of labor, or the extent of aggregate specialization in an economic system.

I came close to saying as much in 1984. My book began:

“To be complex is to consist of two or more separable, analyzable parts, so the degree of complexity of an economy consists of the number of different kinds of jobs in the system and the manner of their organization and interdependence in firms, industries, and so forth. Economic complexity is reflected, crudely, in the Yellow Pages, by occupational dictionaries, and by standard industrial classification (SIC) codes. It can be measured by sophisticate modern techniques such as graph theory or automata theory. The whys and wherefores of complexity are not our subject here, however; it is with the idea itself that we are concerned. A high degree of complexity is what hits you in the face in a walk across New York City; it is what is missing in Dubuque, Iowa. A higher degree of specialization and interdependence – not merely more money or greater wealth – is what makes the world of 1984 so different from the world of 1939.’’

I was interested in specialization as a way of talking about why the prices of everyday goods and services were what they were apart from the quantity of money. I was writing towards the end of 40 years of steadily rising prices. I had become entranced by some painstaking work published 25 years before, by economists E.H. Phelps Brown and Sheila Hopkins. There were measurements of both the money cost of living in England and the purchasing power of workers’ wages over seven centuries. The price level exhibited a step-wise pattern, relentlessly up for a century, steady the next; purchasing power, a jagged but ultimately steady increase (sorry, only JSTOR subscription links).

“[W] hen (I wrote) we find the craftswomen who have been building Nuffield College in our own day earning a hundred fifty pennies in the time it took their forebears building Merton to earn one, the impulse to break through the veil of money becomes powerful: we are bound to ask, what sort of command over the things that builders buy did these pennies give from time to time?’’

It turned out the higher the money price, the more prosperous was the craftsman’s lot, at least in the long run, though sometimes after periods of immiseration lasting decades. That was much as Adam Smith led readers to expect in the first sentence of The Wealth of Nations: “The greatest improvement in the productive power of labor, and the greater part of the skill, dexterity, and judgement, with which it is directed, or applied, seems to have been the effects of the division of labor.” Today’s builders rely on a bewildering array of materials and machines to pursue their tasks, compared to those who built Merton College.

What interested me were intricate questions about the direction of causation. Had prices grown higher because the number of pennies had increased? Or had the supply of pennies grown to accommodate an increasing overall division of labor? To put it slightly differently, in those periods of “industrial revolution” – there had been at least two or three such events – had prices risen because the size of the market and the division of labor had grown, and the quantity of money along with them? Or was it the other way around?

Economists had no hope of answering questions like this, it seemed to me, because they had no good way of posing them. They were in the grip of the quantity theory of money, which at least since the time of the first European voyages to the West, has held that “the general level of prices” is proportional to the quantity of money in the system available to pay for those goods. This is, I thought, little more than an analogy with Boyle’s Law, one of the most striking early successes of the scientific revolution, which holds that the pressure and volume of a fixed amount of gas are inversely proportional. Release the contents from a steel cylinder into a balloon and the container expands. But it still contains no more gas than before. Something like that must have been in the mind of the first person who first spoke of “inflating” the currency. From there it was a short jump to the way that classical quantity theory relies on the principle of plenitude – the age-old assumption, inherited from Plato, that there can be nothing truly new under the sun, that the collection of goods of “general price level” were somehow fixed.

But I was no economist. My book found no traction. By then, however, I was hooked; and within a few years I had found my way to a circle of economists at whose center was Paul Romer, then a professor at the University of Rochester. Romer was in the process of putting the growth of knowledge at the center of economics, but that turns out not to be the whole story, just the beginning of it.

The Yellow Pages are all but gone, casualties of search advertising; other industries that supported themselves by assembling audiences have shrunk (newspapers, magazines, broadcast television). Still others have grown (Internet firms, Web vendors, producers of streaming content). Tens of thousands of jobs have been lost; hundreds of thousands of jobs have been created

I still have the feeling that the important changes in the global division of labor have something to do with the behavior of traditional macroeconomic variables. Romer once surmised that the way into the problem was via Gibson’s paradox – a strong and durable positive empirical correlation between interest rates and the general level of prices, where theory expected to find the reverse. Meanwhile, central bankers are fathoming the mysteries of the elusive Phillips Curve, the inverse relationship between unemployment and inflation.

Which brings me back to 1984. Also in that year, Michael Piore and Charles Sabel published The Second Industrial Divide: Possibilities for Prosperity (Basic). They found their new highly flexible manufacturing firms in northwestern and central Italy instead of Silicon Valley. Their entrepreneurs had ties to communist parties and the Catholic Church instead of liberation sympathies. But the idea was much the same: Computers would be the key to flexible specialization. For all the talk since about economic complexity, that is the book about the changing division of labor worth rereading.

David Warsh, a veteran columnist and an economic historian, is proprietor of Somerville-based economicprincipals.com, where this essay first ran.

Attack by the coal kings?

Mining coal from a mountaintop in Appalachia

From Robert Whitcomb’s “Digital Diary,’’ in GoLocal24.com

At the last moment, just before a federal tax-credit deadline, the Trump regime has announced it will delay a final decision on approving the big Vineyard Wind offshore wind-turbine project for yet more “review’’ of the already studied nearly unto death project. The move means that the project will probably lose the tax credit in effect right now and require congressional and presidential approval to get it renewed – legislation that the coal industry’s most powerful servant, Senate Majority Leader Mitch McConnell, of coal-state Kentucky, might kill.

Does the sudden delay announcement come mostly because the Trumpists want to undermine competition with the fossil-fuel industry, which it’s in bed with, or to stick it to a Democratic part of the nation that would benefit from a big increase in locally created, and clean, energy, or because of complaints from some fishermen? (Wind-turbine towers actually tend to increase the number of fish in the areas where they go up by acting as reefs.)

The delay, or sabotage, might kill the project, by among other things, killing its financing. And it certainly means that the 80-megawatt project for south of Martha’s Vineyard can no longer start generating electricity for 200,000 electric customers (and many more people in those customers’ homes and businesses) by the end of 2021, as had been the plan.

The delay, typical of the interminable red tape and politicization that block other needed infrastructure work in America, will discourage similar windpower projects. Meanwhile, an irony is that the fishermen who oppose Vineyard Wind and similar projects meant to help wean us off fossil fuel are enabling, in their small way, such global-warming effects as hotter seas and ocean acidification that kill off some important fish species. In any event, America continues to be about the worst developed country in which to try to get big projects built. That’s one reason a lot of it’s starting to look like a Third World nation. And whatever happened to Trump’s big plans for infrastructure?

Meanwhile, for an alarming look, with graphics, at how global warming is changing America, please hit this link:

https://www.washingtonpost.com/graphics/2019/national/climate-environment/climate-change-america/

It shows that Rhode Island is a particularly hot spot.

Beloved in our neighborhood

My sweet-sixteen dress was yellow as the daffodils

In the seamstress’s cramped but spotless living room,

Yellow as the sweet lemon bars she made each Christmas

For the neighborhood children.

Mrs. Mueller lived at the end of our block

In a little stone cottage near a field of flowers,

Like a grandmother in a fairy tale.

She was old and poor and crippled

But always tidy, always smiling,

Even as the marshals took her away

After it came to light that, once upon a time,

She was a guard at Auschwitz.

—“Light,’’ by Felicia Nimue Ackerman. This poem was first published in Free Inquiry

Jim Hightower: Americans head for Mexico for health care

Welcome to a health-care mecca for Americans.

Via OtherWords.org

You probably haven’t heard about it, but there’s another mass migration coming across the U.S.-Mexico border.

However, these aren’t Central American families fleeing horrific conditions back home — only to be separated, incarcerated, traumatized, and demonized by Trump for seeking humanitarian asylum in our country.

Rather, these migrants are going the other way — from the United States into Mexican border towns, where they’re welcomed with open arms instead of armed guards.

They’re mostly working-class people seeking relief from our nation’s unaffordable, no-care health care system. As many as 6,000 a day travel to such towns as Los Algodones, across from Yuma, Ariz., to get medical services and prescription drugs that are priced out of their reach here in the United States.

Nicknamed “Molar City,” Los Algodones has more dentists per capita than anywhere else in the world. Quality dental work in Mexico averages two-thirds less than it costs here

This is because the health system there prioritizes care over profits.

Start with professional education, which is tuition-free in Mexico, meaning dentists and other health-care providers don’t have to jack up prices to cover a crushing load of student debt. Also, Mexico’s universal, tax-paid health care system doesn’t saddle patients with exorbitantly expensive insurance bureaucracies.

It’s a system that’s open, affordable, and accessible to all — the opposite of ours, which is why hordes of U.S. working-class people go south to find care. As a Truthout.org article reports, “U.S. citizens seeking health care can park in Yuma for $5, walk across the border, get the help they need, and come back for dinner.’’

Instead of building a senseless border wall to keep people out of the U.S., our leaders ought to be looking across the border for ideas on how to build a better health-care system.

OtherWords columnist Jim Hightower is a radio commentator, writer and public speaker.

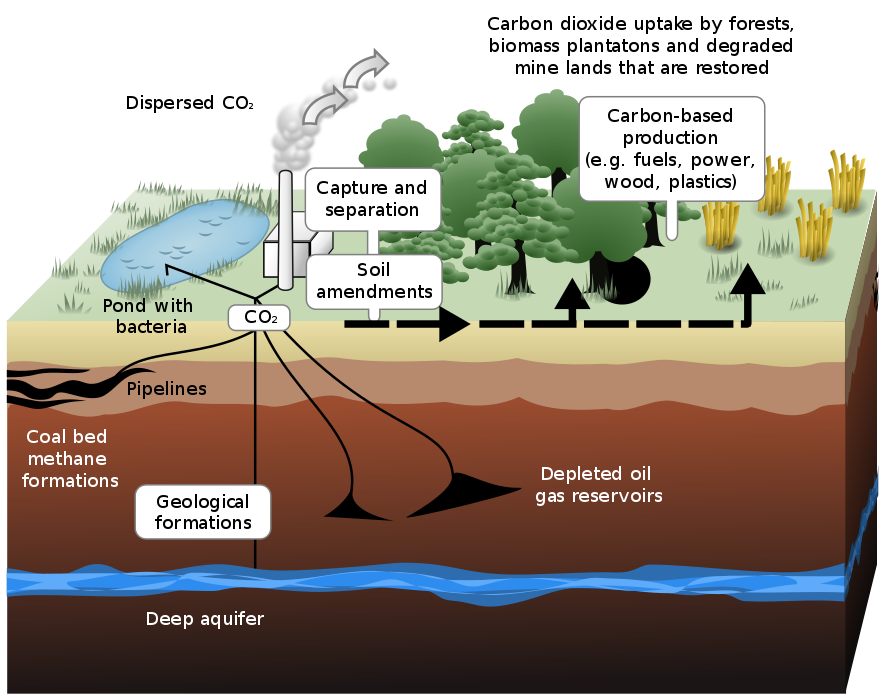

Llewellyn King: Carbon capture may be key to stopping climate catastrophe

Schematic showing both terrestrial and geological sequestration of carbon dioxide emissions from a biomass or fossil fuel power station.

In the ’70s and ’80s, black was gold. Coal was king.

Coal in tandem with nuclear were to be the white knights of the United States, as we struggled with the Arab oil embargo, price-gouging by the Organization of Petroleum Exporting Countries, and declining oil production at home.

In 1977, the fledgling Department of Energy declared natural gas a “depleted” resource. Today, it battles with solar for cost advantage. The technology of fracking changed everything. Never forget technology’s possible revolutionary impact.

Solar and wind -- today’s energy darlings -- were struggling as the National Laboratories sought to make them workable. Solar was thought to have its future in mirrors concentrating heat on “power towers”. Wind was regarded with skepticism; even the shape of the towers and blades was in flux.

Everything that moved would be electrified. Nuclear would be used to make electricity. Coal would be burned as a utility and industrial fuel, and it would be gasified and liquified for transportation and other uses.

Environmentalists were pushing coal as an alternative to nuclear, which they were convinced was dangerous: In the United States it has cost no lives, but gas and oil in various ways have taken their toll.

Coal and nuclear were bright stars in a dark sky.

In 1974, at the White House, Donald Rice, who later ran the Rand Corporation, speculated in an interview with me on whether there might be oil and gas in the Southern Hemisphere, then considered unlikely and now, with production in South America and South Africa, a game-changer. Beware of the conventional wisdom.

All of this came flooding back at an extraordinary summit on global energy horizons convened in Washington recently by Dentons, the world’s largest law firm with offices in 79 countries. By pulling in lawyers from Uzbekistan to London, Dentons’ summit was able to fit America’s energy transformation into the global reality.

Richard Newell, president of Resources for the Future, laid out a picture that is sobering. He said that by 2040, the world would be pumping more carbon dioxide into the atmosphere than today notwithstanding dramatic actions to curb burning fossil fuels in North America, Europe and China. The problem is the growth in demand for electricity in what is being called the “Global East,” where new coal plants are coming online in China, India and Indonesia among other countries. This despite all deploying solar and wind, and India and China having aggressive nuclear growth plans. The electricity need in the region is great and fuel solution is fossil, mostly coal.

Enter Ernest Moniz. The former secretary of energy who now heads his own think tank, Energy Futures Initiative, is a passionate backer of carbon capture use and storage. Moniz, also an adviser to Dentons, is laying out a whole scenario of “carbon capture from air” that is persuasive. It is part of his newly unveiled “Green Real Deal.”

Having chaired two carbon capture conferences, I have wondered why the technology, which gets more sophisticated all the time, has not been embraced by coal producers with vigor. They have been cooler than the utilities who somewhat favor the technology.

Clinton Vince, chair of Dentons’ U.S. energy practice and co-chair of the firm’s global energy sector, reminded the summit of the global importance of nuclear, now shunned in the United States for cost reasons. He sees nuclear as vital to climate goals around the world.

Unlike the ’70s and early ’80s, there is no shortage of energy. The challenges are in how clean it can get; how it can be stored, if it is electricity; and how fast technology can change the energy equation -- as it has over the past four decades -- to save the climate without restricting economic growth.

The commodity that is in truly short supply is time.

Llewellyn King is executive producer and host of White House Chronicle, on PBS. His email is llewellynking1@gmail.com and he’s based in Rhode Island and Rhode Island.

Mike Cross: Going undercover as a student made me a better professor

On the campus of Northern Essex (County) Community College, in Haverhill

From The New England Journal of Higher Education, a service of The New England Board of Higher Education (nebhe.org)

‘Three years ago, I graduated with an associate degree in liberal arts from Northern Essex Community College (NECC) in Haverhill, Mass. Although I was one of over a thousand students to graduate that day, my situation was a little different than those of my peers. You see, I am a full-time faculty member at NECC with a Ph.D. in organic chemistry.

I had decided the year before to go undercover by enrolling as a student. Graduation day marked the end of an intense year of juggling school, work and family responsibilities. Since that day I have been asked two questions whenever someone hears about my experience: “Why on earth would you do such a thing?” and “What did you learn?”

The answer to the first question is simple. I wanted to understand some of the challenges my adult students were facing. I wanted to experience firsthand the struggle of transferring credits, taking the ACCUPLACER placement exam, registering for and attending classes—all while maintaining a full-time job and caring for my three children. This was very different from my days as an undergraduate at a research university where I was a full-time student, fresh out of high school, with a part-time job and no spouse or kids. My hope was that my experiences would help me to better understand the reasons some students drop out while others are able to push through.

What did I learn from the experience? I gained many insights into the struggles of my students and the minds of my fellow educators, but I’d like to focus on five key points with suggestions on what colleges can do to improve.

1. Some of the barriers to student success are small and easily addressed.

Many barriers to student success are small, but they are everywhere. From day one, I was confronted by tiny hurdles. While registering, I was told I had to find and bring in my high school diploma. The fact that I had a sealed transcript of the courses I took while earning a bachelor degree and doctorate wouldn’t suffice. When I took the ACCUPLACER exam, I found that the room was uncomfortably cold and loud. In one classroom, I found the chairs to be so uncomfortable I had a hard time concentrating.

Are any of these issues catastrophic? Of course not. But they are frustrating and they are certainly avoidable. When a student is struggling, even the smallest thing can be the deciding factor in whether or not they decide the hassle of college is worth it. What can we do to help? The simplest solution is to ask our students—and then take their feedback seriously. If students feel that they are heard, they are much more likely to push through the small stuff in order to achieve their goals.

2. Adjunct faculty are unsung heroes, and our colleges need to support them.

I made sure to take classes in all different formats: face-to-face, hybrid, online. And I also made sure to take classes from both full-time and part-time instructors. I had some amazing classes with fabulous full-time instructors but what surprised me the most was the commitment of our part-time instructors. Despite the fact that they are not paid to hold office hours (and many didn’t have an office at all), they often went above and beyond the call of duty to help students.

In fact, one of my favorite classes was a public speaking course taught by an extremely talented adjunct instructor. (On a side note, isn’t it tragic that despite spending every day of my career in front of a classroom of students I had never before taken a public speaking course?) The course was well-organized with clear expectations. The instructor knew that public speaking is a common fear and used humor to help students overcome their fears. He gave excellent feedback and encouraged students to give one another feedback as well.

Since adjunct faculty make such important contributions to the education of our students, we need to be sure they have the support they need. Adjunct instructors often feel isolated and don’t have the same access to resources. I’m pleased that in recent years, my college has increased the resources available to adjunct faculty through our Center for Professional Development. We have adjunct faculty fellows who build community among our adjunct faculty through social media, professional development events and an online toolkit, which provides easy access to needed resources.

3. We need to be clear about what constitutes cheating.

Cheating is rampant … but most students don’t consider what they’re doing to be cheating. In most of my classes, I was able to go incognito for much of the semester. Sitting alongside my fellow students opened my eyes to the sophistication of modern cheating. Gone are the days of crib sheets and bribing your roommate to do your math homework. In today’s classroom, students are constantly pulling up notes on their phone or watch. They use (and gladly share) test bank answers downloaded from any number of internet “study” sites. If you have a credit card, you can have someone online write your research paper or solve your take-home exam for you.

Cheating has always been a problem, so I wasn’t surprised to see that it is still an issue today. But I was surprised to find that many students don’t consider what they are doing to be cheating. They consider texting answers to classmates just “being a good friend.” Downloading publisher test banks is simply “using your resources.” Although it’s impossible to prevent all cheating, I believe the fastest and easiest way an instructor can reduce it is to make it clear what you consider to be cheating. Going over the do’s and don’ts of ethical behavior during the first week of class is a major deterrent to cheating for many students.

4. Faculty members should push through the fear and be open to new experiences that provide them with feedback on their teaching.

At the start of each semester as a covert “student,” I would try to meet with each of my instructors and let them know who I was before showing up to the first day of class. In almost every case, the faculty member would appear nervous, but would welcome me to the class and ask me to provide them with feedback throughout the semester.

There were a few professors who were not so open to having me as a student. One didn’t want me in her class for fear that I was secretly evaluating her for the administration. Another told me that by enrolling in classes at our community college, I was undervaluing the “real education” I had received during my previous undergraduate career at a university.

No one is immune to impostor syndrome. It is natural to feel anxious about new experiences, especially when those experiences may expose our shortcomings (either real or imagined). I have felt this myself as I have had a colleague take one of my classes recently. It’s an intimidating experience, but I have tried to use it as a chance to reevaluate and improve my teaching. We should be open to feedback and criticism, whatever the source may be.

Over the past year I have had the privilege of co-facilitating the Teaching and Learning Academy with one of our adjunct faculty fellows (and my former professor). The academy allows faculty to come together in a relaxed environment and discuss life in the classroom. Over the course of the semester, we visit each other’s classes and share honest feedback. Opportunities like this improve our teaching and build our sense of community.

5. It’s easy to forget what it is like to be student.

How many times have you heard colleagues say, “When I was a student …”? This phrase is usually followed by a condemnation of the current crop of students. We forget that we are just like our students. For example, in one of my classes, the professor had a strict no cell phone policy. Yet while students were doing group work, he would pull out his cell phone to check social media. We must hold ourselves to a higher standard than our students. If faculty lock the door to prevent late students from entering, they must be sure to never be tardy themselves. If we expect students to turn in work on time, we should be prepared to return exams and give feedback in a timely manner.

While not every experience I had while undercover was positive, it was truly the best professional development of my career. It rekindled my love of learning. When I registered for classes at NECC I found out that I was required to take English Composition II, as I had never actually taken it as an undergraduate. Despite my dread, I ended up loving the course. When my instructor informed me that she would like to nominate one of my papers for a writing award, I almost cried. This was the first time in all of my years of higher education that someone told me that I was good at writing.

Too often we refer to a Ph.D. as a terminal degree, as though our education is dead (or at least on life support). Most of us went into education because we love to learn, but between grading, curriculum development and committee work, it’s easy to forget the thrill of learning something new. Sitting alongside my students as we learned together not only helped me better appreciate their daily struggles, but it reminded me that we are on this educational journey together.

Mike Cross is a professor of chemistry at Northern Essex Community College.

Rachel Hodes: What 'abolish ICE' really means

Via OtherWords.org

To most of America, “abolish ICE” is a cry of the far left. Even Americans who dislike Trump’s attacks on undocumented immigrants wouldn’t necessarily tell you that ICE should be abolished; that seems far too radical. ICE stands for the U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement agency.

They’re forgetting that ICE is actually pretty new. It was only created in 2003, replacing the Immigration and Naturalization Service (the same agency responsible for the internment of Japanese-Americans in the 1940s).

Since its creation, ICE’s budget has almost doubled, and its activity has expanded to triple the number of agents it employs. This expansion is shocking — and unwarranted. All evidence suggests that immigrants are far from the national security threat the Trump administration claims they are. Regardless of status, they’re more law-abiding than native-born citizens.

And time and time again, immigration has been shown to have a net-positive effect on the U.S. economy, from growing tax receipts to increasing wages for native-born residents. In fact, undocumented immigrants typically pay more of their income in taxes than your average millionaire.

More noteworthy than the economics, however, is that the individuals targeted by ICE are people — and all people are entitled to basic conditions of safety and for themselves and their families.

When the majority of these immigrants are fleeing violence with roots in U.S. intervention in Central America, the moral responsibility to offer safe haven becomes even more pressing. When government agencies neglect this responsibility, we all lose some of our humanity.

What calls to abolish ICE actually do is beg the question: Why do we need an immigration system dedicated solely to terrorizing immigrant communities?

Threats of ICE raids prevent undocumented people from going to work or sending their kids to school. Those in detention are denied access to basic hygienic products, subjected to severe overcrowding, and experience all manner of abuse. Several children have died.

We spend about $7 billion a year on ICE. What would happen if we instead invested those funds in resettling asylum-seekers, or hiring more staff to process asylum applications? What if families fleeing violence in Honduras or Guatemala had to wait only a few weeks to find out if they could immigrate legally, as opposed to the current average of almost two years?

The U.S. carried out over a quarter million deportations last year. The $7 billion that funded these actions

could have been used instead to resettle at least that many refugees (over 11 times what the U.S. accepted last year). It could also almost triple the funding of the government office that naturalizes around 700,000 new citizens each year.

Which is more radical: Investing in communities that strengthen our country and honoring basic human decency? Or continuing to fund an agency that’s literally caused the death of children?

As a concerned Jewish American, I believe none of us are safe until we’re all safe. We should be focusing our resources on welcoming new immigrants and helping them access the rights of citizenship — not subjecting them to detention and deportation.

A better world, for immigrants and for everyone, is within our reach. ICE just isn’t a part of it.

Rachel Hodes is a Next Leader at the Institute for Policy Studies.

Developing human+ skills in students so they can thrive in workplace

From The New England Journal of Higher Education (NEJHE), a service of The New England Board of Higher Education (nebhe.org)

“The world will need more agile and resilient thinkers with a serious handle on various technologies and digital literacies.”

Michelle Weise is senior vice president for workforce strategies and chief innovation officer at Strada Education Network. Weise is a higher education expert who specializes in innovation and connections between higher education and the workforce. She built and led Sandbox ColLABorative at Southern New Hampshire University (SNHU) and the higher education practice of the Clayton Christensen Institute for Disruptive Innovation. With Christensen, she co-authored Hire Education: Mastery, Modularization, and the Workforce Revolution, a book that focuses on how to align online competency-based education with changing labor market needs.

In the following Q&A, NEJHE Executive Editor John O. Harney asks Weise about her insights on connecting postsecondary education to the world of work.

Harney: The relationship between education and employability seems widely understood now. What’s truly new in this area?

Weise: What’s different today is that with all the trending conversations about the future of work, the new narrative is that the most valuable workers now and in the future will be those who can combine technical knowledge with uniquely human skills. Over the last few decades, students have moved in large numbers to career-oriented majors, such as business, health and engineering—clearly hearing that the surest path to a meaningful, financially stable career is also the most straightforward one. Those pursuing liberal arts degrees, on the other hand, are on the decline. Policymakers have been particularly down on the outcomes of liberal arts, questioning the value of these majors as relevant to the challenges ahead.

But it’s not either/or; it’s both/and. Human skills alone are not enough and neither are technical skills on their own. This runs somewhat counter to the rallying cries in the 2000s, warning of a dearth of STEM majors to meet the demands of the emerging tech-enabled knowledge economy. But not all of the jobs will require STEM majors or data science wizards or people who fully grasp the technicalities of artificial intelligence. There are differing levels of depth and shallowness of that technical expertise needed alongside human skills that are in high demand.

With that nuance comes the need for real-time labor market data. Fortunately, with partners like Emsi, we can now extract the skills from job postings from businesses (demand-side data) and social profiles and resumes from people (supply-side data), and begin to look underneath traditional occupational classification schemes to observe how specific knowledge and skills cluster with one another. By doing this, we can more clearly diagnose the realities of work, education and skills requirements, and how skills develop and morph across regions and industries. This is essential because it gives learning providers insights that are more current and certainly more accurate, so that they may develop and refine curriculum and advise learners for a rapidly changing workplace.

Harney: Strada’s work regarding “On-ramps to Good Jobs” explicitly references “working class Americans”? Who are they and what are some of the learn-earn-learn strategies with the best traction?

Weise: We use the term “working class” to refer to people who represent the lowest quartile of adults in terms of educational attainment, earnings, and income (26%). We estimate that there are approximately 44 million working-class adults who are of working age (25- to 64-years-old) earning less than $35,000 annually and with less than $70,000 of family income.

What we call on-ramps to good jobs are programs designed, tailored and targeted for these learners with significant barriers to educational and economic success. Some of the most interesting models we found leveraged a “try-before-you-buy” outsourced apprenticeship model. Unlike in traditional apprenticeship models, the employer of record is the on-ramp, and the hiring employer acts as a client to the on-ramp. Apprentices are paid by the on-ramp but work on projects for client firms that are testing out that particular apprentice as a future job candidate. These models are great ways of building steady revenue streams that are sustainable, so that on-ramps reduce dependence on philanthropic or government dollars.

LaunchCode, a St. Louis-based tech bootcamp, hires and manages apprentices from its own program and, in turn, charges businesses $35 an hour for services. If, at program’s end, the employer hires an apprentice, the employer does not have to pay a placement fee, as LaunchCode’s overhead costs have been covered by the hourly service charge paid by employers during the training and pre-hire apprenticeship period.

As another example, Techtonic, a software development company based in Denver, has implemented an outsourced apprenticeship, now certified by the U.S. Department of Labor. Candidates are screened and then put through 12 weeks of training, akin to a coding bootcamp. After learners finish their training, Techtonic “hires” the apprentices, pays them entry-level wages, and pairs them with senior developers to work on projects for its clients. Not only do apprentices get paid for work, but they also simultaneously develop and hone the skills they will need for long-term career success. At the same time, Techtonic’s client firms have a seamless, low-stakes way of evaluating a candidate’s work before committing to full-time employment.

Harney: You also reference “good/decent jobs” … what do these entail?

Weise: We’re talking about jobs that have strong starting salaries that can move a person out of low-wage work to be able to thrive in the labor market by making at least $35k per year as an individual, and a lot more than that in many cases. This is critical for the bottom quartile of working-age adults in terms of educational attainment, earnings and income. We now have 44 million Americans who are jobless or lacking the skills, credentials and networks they need to earn enough income to support themselves and their families. We need better solutions for our most vulnerable citizens.

So when we talk about a good job, we’re not just talking about a well-paying, dead-end job; we’re looking at jobs that have mobility built into them. We want to focus on jobs with promise, or the ability to advance and move up.

Harney: What is the role of non-degree credentials in our understanding of education and employability?

Weise: We know that when people pursue postsecondary education, their main motivation is around work and career outcomes. If they can get there without a degree, is that enough for some? And what about folks who already have degrees who want to advance with just a little bit more training? More college or more graduate school will not be the answer. Flexibility, convenience, relevance … these may be attributes that are much more alluring than the package of a degree.

The business of skills-building is mostly occurring within the confines of federal financial aid models and the credit hour, but there’s an even wider range of opportunities to dream up innovative funding models and partnerships with employers. I’m eager to see more solutions that tie in with the training and development \or learning and development sides of a business rather than through the human resources side of tuition-reimbursement benefits. Where are the employers innovating new forms of on-the-job training?

This, by the way, is a huge opportunity for competency-based education (CBE) providers to serve, but everyone’s busy creating new CBE degreeprograms. What makes CBE disruptive, which is what Clayton Christensen and I pointed to in Hire Education, is that when learning is broken down into competencies—not by courses or subject matter—online competency-based providers can easily arrange modules of learning and package them into different, scalable programs for very different industries. For newer fields such as data science, logistics or design thinking that do not necessarily exist at traditional institutions, online competency-based education providers can leverage modularization and advanced technologies and build tailored programs on demand that match the needs of the labor market.

Harney: Can an employability focus go too far in terms of turning education into a purely vocational endeavor? As an English major and expert in literature and arts, what are your concerns about how steps such as gainful employment guidelines could discourage students from going into such fields and teacher prep, for example?

Weise: That was actually one of the motivations for clarifying the outcomes of liberal arts grads in the labor market. Current views on the liberal arts are often polarizing and oversimplified, and so we wrote “Robot-Ready: Human+ Skills for the Future of Work.” This paper was designed to bring more nuance and rigor to the conversation. Liberal arts graduates are neither doomed to underemployment, nor are they prepared to do anything they want. The liberal arts can give us the agile thinkers of tomorrow, but to live up to their potential, they must evolve. The liberal arts are teaching high-demand skills that can help people transfer from domain to domain, but they do not provide students with enough insight into the pathways available and the practical grounding to acquire before they graduate. In this analysis, we show precisely the kinds of hybrid skills needed in the top 10 pathways that liberal arts grads tend to pursue.

As a quick example, if we have learners considering journalism, they need to know that the roles available now resemble those in IT fields. Not only must journalists report, write or develop stories, but they must also demonstrate metrics-based interpretive skills, fluency in analytics capabilities like search engine optimization (SEO), JavaScript, CSS and HTML, and experience using Google Analytics to better understand who is accessing their content.

A liberal arts education can, in fact, enable learners to learn for a lifetime, but it’s not some magical phenomenon. It takes work, effort and awareness to identify the skills that enable learners to make themselves more marketable and break down barriers to entry.

Harney: What will future workers need to work effectively alongside artificial intelligence?

Weise: The literature on the future of work points us to the more human side of work. The research underscores the growing need for human skills such as flexibility, mental agility, ethics, resilience, systems thinking, communication and critical thinking. The idea is that with the rapid developments in machine learning, robotics and computing, humans will have to relinquish certain activities to computers because there’s simply no way to compete. But things like emotional intelligence or creativity will become increasingly critical for coordinating with computers and robots and ensuring that we are indispensable.

The question then becomes: What are we doing in a deliberate way within our learning experiences—at schools, colleges, companies, government—to cultivate these uniquely human skills? I think we can be doing a whole lot more in terms of building robot-ready learners of the future through project-based learning. It’s nothing new; It occurs in pockets but is not nearly widespread enough. Ultimately, it gets us those nimble thinkers of the future.

Real-world human problem-solving is transdisciplinary by nature, tapping into varied skills and knowledge—and yet, our postsecondary system remains stubbornly stovepiped. Students must learn—and be taught—to connect one domain of knowledge to another through what is known as “far transfer.”

But again, human skills alone are not enough: It’s human+. The world will need more agile and resilient thinkers with a serious handle on various technologies and digital literacies. Those workers will need both human and technical skills. With stronger problem-based models, it’ll be easier for education providers to stay ahead of the curve and build in new and emerging skill sets in data analytics, blockchain, web development or digital marketing that students will need in order to be successful in the job market. The integration of more project-based learning into the classroom would bring more clarity to how human+ skills translate into real-world problem solving and workplace dexterity.

David Warsh: The young and the restless in presidential politics

SOMERVILLE, Mass.

It has long seemed to me that the United States began to lose its way in 1992, when Bill Clinton defeated George. H. W. Bush for the presidency. The Berlin Wall had fallen. The Soviet Union had disbanded. The Cold War had ended. Bush was highly popular in the wake of the First Gulf War.

Leading Democrats – such as Gov. Mario Cuomo, Jesse Jackson and Sen. Al Gore — declined to run. (Gore’s son had been gravely injured in an auto accident.) Instead, Gov. Bill Clinton, former Gov. Jerry Brown, Senators Paul Tsongas, Bob Kerrey and Tom Harkin all joined the chase.

Bush reappointed Alan Greenspan as chairman of the Fed, but later charged that Greenspan reneged on a promise to ease monetary policy slightly, to compensate for the tax increase that Bush had requested to pay for the war and the mild recession (July 1990-March ’91) that had resulted. The recovery in the year before the election was unusually tepid.

Populist commentator Pat Buchanan ran against Bush from the right in Republican primaries. Though he won no states, he polled more votes than expected, especially in New Hampshire. As Buchanan faded, an emboldened H. Ross Perot entered the campaign as an independent candidate, exited, and re-entered. He won 19 percent of the popular vote in the end but failed to gain a single electoral vote.

Clinton won the election. After 12 years as vice president and president, Bush was all-too-familiar; Clinton was fresh. Bush had been the youngest Navy pilot in World War II. Clinton was a Baby Boomer who skipped Vietnam. Bush lacked energy; Clinton was a dynamo.

America enjoyed a few years of exhilaration in the Nineties: the introduction of the Internet; a dot.com mania; and, thanks to eight years of brisk growth, a balanced federal budget, after 20 years of surging deficits,. Looking back, though, Clinton was ill prepared by his years as Arkansas governor to make foreign policy. Two years as a Rhodes Scholar at Oxford had made him overconfident as well.

Unilateral humanitarian interventions followed in the Balkan civil wars that flared after the Soviet Union collapsed. NATO expansions were undertaken that the Bush administration, expecting a second term, had promised would not occur. Russia protested, but was powerless to prevent any of it. Vladimir Putin replaced Boris Yeltsin and grew increasingly resentful.

Without the discipline imposed by of the Cold War, domestic politics turned rambunctious as well. Clinton empowered his wife to seek to overhaul U.S. health insurance. Congressman Newt Gingrich replied with his “Contract with America,” gained 54 House seats and 9 Senate seats in the 1994 mid-term elections. Republican enmity toward Clinton, which had begun to overspill the bounds of decency soon after the inauguration, reached flood levels with the impeachment and failed conviction proceedings of Clinton’s second term.

The next two presidencies, 16 years, amounted to more of the same. NATO expansion continued, reaching the borders of Russia. Relations with China remained amicable throughout. George W. Bush started wars in Afghanistan and Iraq. Barack Obama pursued regime change in Libya (successfully) and Syria (unsuccessfully). The third presidential go-round, which started out in 2015 as a presumed Bush-Clinton rematch (Jeb Bush vs. Hillary Clinton) is what eventually got us to Trump.

Now Americans may be about to do it again – to prefer youth and personal ambition to consensus. The situation today is a little like 1992 in reverse. An over-abundance of Democratic Party candidates are eager to take on Donald Trump (or, in the event that he prefers not to run, Vice President Mike Pence). California Sen.

Kamala Harris damaged former Vice President Joe Biden in the debate last week. She projected youth and vigor. Biden was cautious; he had to contend with his record over 44 years of swiftly changing national politics. That Harris used the murky issue of federal court-ordered busing to attack Biden struck me as especially low. Nevertheless, Harris emerged as a candidate capable of taking on Trump. Her next challenge will be to finesse the health-care issue that handcuffed her in the debate.

She is also the candidate to watch out for, as Clinton was the candidate to watch out for in 1992. Clinton’s character didn’t come into focus until 1995, when First in His Class, David Maraniss’s brilliant biography, appeared. Harris will presumably receive a series of earlier screenings. Her appeal to her base, women and African Americans, is obvious. It remains to be seen whether she can persuade swing constituencies near the center of American political life,

Leaping far ahead, my guess is that only a better-than-expected showing by Biden or South Bend Mayor Pete Buttigieg in the California primary on Super Tuesday, March 3 (if they survive that long), will force Harris to wait. Bill Clinton would have been a much better president if he had first been elected in 1996. Mitt Romney might have defeated Hillary Clinton if he had waited until 2016.

But the young and/or the restless have dominated the top of the food chain for the last 28 years. True, it was John F. Kennedy who first jumped the queue, an element of collective memory that Clinton employed to enhance his license. With the exception of Barack Obama, they haven’t been good for the country.

David Warsh, an economic historian and long-time columnist on business, politics and media, is proprietor of Somerville-based economicprincipals.com, where this essay first ran.

John O. Harney: Atlantis in New England and other topics

Athanasius Kircher's map of Atlantis, placing it in the middle of the Atlantic Ocean, from Mundus Subterraneus (1669), published in Amsterdam. The map is oriented with south at the top.

Ruminations from John O. Harney, executive editor of The New England Journal of Higher Education, a service of The New England Board of Higher Education (nebhe.org)

Unvites. I recently enjoyed a fascinating panel discussion on Protesting the Podium: Campus Disinvitations sponsored by the Bipartisan Policy Center. The panelists were former U.S. Sen. Bob Kerrey, Harvard professor Harvey C. Mansfield, Middlebury College professor Matthew J. Dickinson and Wesleyan University President Michael S. Roth. They all had some kind of run-in with once-again radioactive speech issues on campus … and they were all smart as whips. Dickinson said he prefaces his classes now by telling students they are not in a “safe space,” but rather in a place where issues will be discussed using intellectual debate and that all students must be heard, especially marginalized students. Kerrey, also former president of the New School, worried that amidst the clamor of so much social media, people have to resort to insult to be heard. Roth, who acknowledges a certain “affirmative action” for conservative ideas, noted that students are suspicious of free speech to advance certain agendas, particularly when it is “weaponized” by money and technology.

Diversifying study-abroad. Minority Serving Institutions (MSIs) enroll over 25% of all U.S. college students, but accounted for just 11% of all U.S. study-abroad students in the 2016-17 academic year, according to a report by the Center for Minority Serving Institutions and the Council on International Educational Exchange. The report focuses on the obstacles that discourage students from studying abroad, including barriers of cost, culture and curriculum, which may be worse at MSIs. A small step forward: The report highlights the Frederick Douglass Global Fellowship created by the two organizations to cover costs for 10 outstanding MSI students to participate in a four-week study-abroad program focused on intercultural communication and leadership.

Batten down the hatches. The U.S faces more than $400 billion in costs over the next 20 years to defend coastal communities from inevitable sea-level rise, according to a study done by the Center for Climate Integrity in partnership with the engineering firm, Resilient Analytics. The study looked at thousands of miles of coastline to determine areas that are at risk of being at least 15% underwater by 2040 due to rising seas and land-based ice melts. In New England, the study forecast that seawalls needed by 2040 would cost about $19 billion for Massachusetts, $11 billion for Maine, $5 billion for Connecticut, $3 billion for Rhode Island and $1 billion for New Hampshire. What does this have to do with higher ed? Of course, climate change has to do with everything. But more specifically, see NEJHE’s A Modest Proposal to Save the Planet.

Watched pot. Clark University in Worcester, Mass., this fall will launch America’s first Certificate in Regulatory Affairs for Cannabis Control, a three-course online graduate certificate program designed to help professionals, ranging from police to pot vendors, to understand the complications, opportunities and risks associated with the industry. Worcester will also be the future headquarters of the Massachusetts Cannabis Control Commission—and incidentally, the new home of the Pawtucket Red Sox, Exhibit A (along with GE) in the building case of New England’s not-quite team spirit in site planning.

Benefits. A MAVY poll on behalf of the American Institute of CPAs asked “young adult job seekers” to name the employees benefits that would most help them achieve their financial goals. The top choices were: 1) health insurance, 2) paid time off, 3) student loan forgiveness and 4) working remotely. The CPA group played up the high ranking of student loan debt, and indeed, 2020 presidential candidates are energized by the issue. MAVY polls are developed by the University of Florida and partners and focused on millennials. This one defined “young adult job seekers” as millennials who graduated from college in the past 24 months or will graduate in the next 12 months and are currently looking for employment.

John O. Harney is executive editor of The New England Journal of Higher Education.

David Warsh: Trump, North Korea and China

North Korean soldier points to the demilitarized zone between the two Koreas.

From economicprincipals.com

SOMERVILLE, Mass.

One consequence of government by bluster and contempt is that, even when Donald Trump is right, the president is unable to make the case for his policies. Take those “beautiful letters” he keeps getting from Kim Jong Un, leader of North Korea. The editor of a new book of essays outlines the logic that Trump has failed to present.

North Korea: Peace? Nuclear War? (Mosavar-Rahmani Center for Business and Government, 2019 ), edited by William Overholt, contains 18 essays by leading Korea specialists, including one by China’s foremost expert on Korean affairs and another by former U.S. Ambassador to Korea Kathleen Stephens, who as U.S. chargé d’affaires in Belfast oversaw Northern Ireland’s Good Friday agreement. (Stephens first learned Korean as a Peace Corps volunteer, before entering the Foreign Service.) A wide range of views are represented, but the authoritative voice in the volume belongs to Overholt. His summary is here. In a separate letter about the book, the veteran Asia hand compressed the argument of his essay.

“A strategy of forced denuclearization by bludgeoning through sanctions has no chance of success. A strategy of achieving denuclearization as a byproduct of achieving peace has some chance of success.’’

North Korea invaded South Korea in 1950, backed by Stalin and Mao Zedong. U.N. forces, led by the United States, defended the south. Soon Chinese troops and Soviet pilots supported the north. The war ended in stalemate in 1953. North Korea has been ruled ever since by three generations of the Kim family: Kim Il Sung, until 1994; his son, Kim Jong Il, until 2011; and his grandson, Kim Jong Un, since the death of his father.

The situation has changed over the years, says Overholt: gradually since 1978, when China put aside autarkic revolutionary ideology and began its “great leap outward” into the global market economy; rapidly, after 2011. As a scion of the ruling dynasty, Kim Jong Un was educated, among other places, in Switzerland. He has absorbed the lessons of an Asian style of development strategy that has lifted almost all of the region to prosperity. He also has a longer time horizon than his father, says Overholt. His father had been 57 when he acceded to power.

Kim has risked his position by imposing very different budget priorities from those of his father and grandfather, including the development of nuclear weapons. He has opened his country socially, at least to the extent that North Korean citizens now know what they are missing. He has employed traditionally brutal methods to protect his power.

The U.S. has replied with sanctions, demanding denuclearizaion before any relief. Both sides have good reason to mistrust one another, Overholt says. North Korean behavior in the past often has been deceptive, unreliable, and vicious. The US pursued a policy of “regime change” in Libya after Muammar Gaddafi de-nuked and set an alarming example.

But the situation in China has changed, too, in the space of years since it became a great power. China’s policy is to stabilize the peninsula. Any deal will require Chinese security guarantees for the North Korean regime. South Korea will have to agree, too. The South Korean population is fully supportive of the peace process; its government is fully engaged. So are the Chinese and U.S. negotiators, especially after Kim was said to have executed one of the negotiators and four other advisers after the breakdown of his second summit with the American president.

Time is short, Overholt says. “Kim is vulnerable and may be overthrown or killed if there is no early progress toward peace and economic development. His opponents want a return to the old military priorities and confrontational ways. Kim Jong Un has promised de-escalation, but only in stages and over a considerable period of time. Trump and Kim and their respective advisers are thus in somewhat parallel positions, dealing with a national establishment that looks to the past instead of the future. Overholt: “Early incremental but decisive progress is the only hope.”

Trump can’t do the job of building support for a China-mediated agreement to begin to lift sanctions, and the press won’t do it for him. The Great Successor: The Divinely Perfect Destiny of Brilliant Comrade Kim Jong Un (TK, 2019), by Anna Fifield, of The Washington Post, has just appeared. It looks interesting, in this adaptation from the book on Kim’s four years in Europe, or this New Yorker interview with the author. But the ridicule of the title delivers her ultimate judgment. There is much to object to about both Kim Jong-un and Donald Trump. Failing to seek to act on an urgent problem is not among them.

. xxx

Martin Feldstein died June 11, at 79. A Harvard University professor and long-time president of the National Bureau of Economic Research, he was the most influential policy economist of the Reagan generation. He was remembered by The Wall Street Journal, the Financial Times, The New York Times, The Washington Post, and The Economist. Economic Principals appreciated Feldstein in 2008, on the occasion of his retirement from the NBER. Friends who provided encouragement and social support to the engagement of a Long Island Jew and an Irish Catholic from Boston consider Feldstein’s marriage to Kathleen Foley Feldstein, also an economist, to have been spectacularly successful.

. xxx

Added this week to EP’s Bookshelf: Fault Lines: A History of the United States since 1974, by Kevin Kruse and Julian Zelitzer (Norton, 2019)

David Warsh, a Somerville-based veteran columnist and economic historian, is proprietor of economicprincipals.com.

'Invisible forces at work'

From Elizabeth Keithline’s site-specific installation, “(The Air) As It Moves,’’ at the University of Massachusetts at Dartmouth Art Gallery, in New Bedford, through Sept. 12. The gallery explains that Ms. Keithline uses “hanging wire objects to create a play of light and shadows as it moves in the air. These abstract shapes have a ‘memory’ of suspended skeletal, swaying wire beams and rafters that invite viewers to contemplate the invisible forces at work in our lives. We see these forces only because of their ancillary activity, never directly. Viewers are invited to move through the gallery and, by doing so, gently activate the installation.’’

The installation is one of four projects in the gallery connected to the theme of wind and inspired by the inaugural Design Art Technology Massachusetts (DATMA) festival, titled ‘‘Summer Winds 2019’’.

May 24 - September 12, 2019

Location: University Art Gallery, Star Store Campus, 715 Purchase Street, New Bedford, MA

Reception: Thursday, AHA! Night, June 13, 6-8.30 pm

7 pm: Artist Talk

7.30 pm: Summer Winds concert with musicians Laura Pardee Schaefer (oboe) and Daniel Beilman (bassoon) from New Bedford Symphony Orchestra

Interactive Shadow Drawing: July 11 & August 8, 6-8 pm

Closing Reception: Thursday, AHA! Night, September 12, 6-8 pm

Contact : Viera Levitt, Gallery Director and Exhibition Curator, gallery@umassd.edu

Hours: 9 AM to 6 PM daily, closed on major holidays. Open until 9 pm during AHA! Nights (the second Thursday of every month)

The UMass Dartmouth University Art Gallery presents four projects connected to the theme of wind throughout the Star Store Campus in Downtown New Bedford. Inspired by the inaugural Design Art Technology Massachusetts (DATMA) festival, titled Summer Winds 2019, visitors can experience various installations and video projects from different artists: Rhode Island's Elizabeth Keithline presents a site specific installation (The Air) As it Moves at the University Art Gallery; Spencer Finch, a well-known New York City artist exhibits Wind (Through Emily Dickinson's Window) in Gallery 244; videos by Renee Piechocki and Brandon Forrest Frederick play at the Bubbler Gallery. Lastly, a project Whispers by Canadian based Light Society will be projected on the Lecture Hall wall only during AHA! Nights, and is not to miss.

(The Air) As It Moves is a site-specific installation by Elizabeth Keithline that uses hanging wire objects to create a play of light and shadows as it moves in the air. These abstract shapes have a “memory” of suspended skeletal, swaying wire beams and rafters that invite viewers to contemplate the invisible forces at work in our lives. We see these forces only because of their ancillary activity, never directly. Viewers are invited to move through the gallery and, by doing so, gently activate the installation.

Throughout the sumer, the walls will become populated by additional shadow drawings, which will make it hard to distinguish the real shadows from their drawings, creating a disorienting and off balance feeling. On July 11 & August 8, there will be a family-friendly interactive shadow drawing from 6 to 8 pm.

Artist Elizabeth Keithline’s work focuses on human self-extension and its effects on contemporary society. Born in Connecticut in 1961, Keithline has been a weaver since she was 14 years old. In 1996, after moving to Rhode Island, she invented a sculpture technique wherein wire is woven around an object and then burned out, leaving behind a wire “memory”. As the installations grew, she began to cut away and re-mend parts of the wire, rather than burning it out. The “spines” that the repairs incorporated became part of the work's content area. She has installed public art projects in Boston, Paxton, and Oxford, MA. A current project, "The Shadow Tree" is installed in the Art & Nature Center at the Peabody Essex Museum through March 2021.

Keithline’s work has been reviewed in the New York Times, Sculpture Magazine, the Boston Globe, the Hartford Courant and others. She is also the consulting director for the Rhode Island State Council On the Arts Percent For Art Program and the State’s Cultural Facilities Grant and serves on the advisory committee of Public Art Review.

Deadly work

Man at the Wheel, Fisherman's Memorial Cenotaph, in Gloucester.

“There are houses in Gloucester where groves have been worn into the floorboards by women pacing past an upstairs window, looking out to sea….If fishermen lived hard, it was no doubt because they died hard as well.’’

— Sebastian Junger, in The Perfect Storm (1997)

“Gloucester Harbor”” (circa 1877), by Richard Morris Hunt