David Warsh: MIT: The 'Duffy's Tavern' of American economics

SOMERVILLE, Mass.

As something of beat reporter, I have half a dozen good stories about economics at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology in various stages of preparation. So what to make of a recent book, #mit and the Transformation of American Economics (Duke, 2014).

I love it, naturally. Not only does it contribute fundamentally to our knowledge of how Paul Samuelson and Robert #solow at MIT more or less invented the field we call macroeconomics and came to dominate the field for a time, but it illuminates the difference between history and journalism.

Transformation is the hardbound annual supplement to the journal History of Political Economy, which is published quarterly by Duke University Press. Each year a research conference assembles an array of scholars writing on a single broad topic; 18 months later, suitably edited, their papers appear in book form. The topic of the conference to be held next month is “Economizing Mind, 1870-2015: When Economics and Psychology Met… or Didn’t.”

Each volume is in conception the creature of an organizing editor, in this case, E. Roy Weintraub, a Duke professor of economics who, one way or another has been on the trail of the MIT story for nearly 40 years. He is the author of, among other books, How Economics Became a Mathematical Science, and last year, with Till Düppe, of Finding Equilibrium: Arrow, Debreu, McKenzie and the Problem of Scientific Credit (Princeton, 2015).

In an introduction, Weintraub lists six competing explanations that have been advanced to account for MIT's rise to the top of the economics profession:

The oldest narrative and most familiar invokes a Keynesian Revolution, swift transformation in which a mimeographed version of The General Theory of Employment Interst , carried to Harvard by Canadian graduate student Robert Bryce, converted first a circle of graduate students, then Harvard Prof. Alvin Hansen, and finally wunderkind Paul Samuelson, who promptly decamped to the technological institute down the street. There is no better account of this version than The Coming of Keynesiaism to America: Conversations with the Founders of Keynesian Economics (Edward Elgar, 1996), edited by David Colander, of Middlebury College, and Harry Landreth, of Centre College.

A second narrative emerged in From Interwar Pluralism to Postwar Neoclassicism a HOPE conference volume from 1998 edited by Mary Morgan, of the London School of Economics, and Malcolm Rutherford, of the University of Victoria. The theories of demand, production and the firm had all been matters of contention in the 1930s, but by the mid-1950s, Weintraub writes, all were settled chapters in graduate and intermediate microeconomic textbooks. How were they thus “stabilized?” It couldn’t have been the highly literary Keynes. Instead it was the new importance that others attached to the role of models and measurement, a thesis elaborated by Morgan in The World in the Model: How Economists Work and Think(Cambridge, 2012) and further illuminated by Weintraub.

A third set of stories emphasizes the effects of World War II: the United States; post-war hegemony overwhelmed various national traditions, especially in Britain and Vienna. Only the U.S. had the resources to educate, train and employ economists, so naturally the science came to be spoken with an American accent. Roger Backhouse, of the University of Birmingham and the University of Rotterdam, editor, with Philippe Fontaine, of The History of the Social Sciences since 1945, (Cambridge, 20120), contributes an essay to the current volume, ”MIT and the Other Cambridge,” describing the 15-year battle known as the “capital controversy” through which the American Cambridge took control.

A fourth interpretation contends that the Cold War turned economics and game theory into a Procrustean bed for purposes of exercising social control. None has gone further down this road than Philip Mirowski, of the University of Notre Dame, in Machine Dreams: Economics Becomes a Cyborg Science, (Cambridge, 2002), but Mirowski is not represented in the current volume. Instead essay on the history of operations research, by William Thomas, of History Associates, Rockville, Md., is said to refute Mirowski’s central claim.

Yet another version puts demand for economists; services at the heart of the story, first at MIT, where interest in the “new economics” was greatest, then at several other schools of business and engineering, especially Pittsburgh’s Carnegie Institute of Technology (today Carnegie Mellon University), as described in The Roots, Rituals and Rhetoric of Change: North American Business Schools After the Second World War (Stanford, 2011), by Mie Augier, of the Naval Post Graduate School, and James March, of Stanford University. The role of the GI Bill of Rights in re-shaping U.S. higher education plays a central role here.

A sixth factor, advanced by Weintraub in the Transformation volume, argues that the rise of MIT stemmed from its willingness to appoint Jewish economists to senior positions, starting with Samuelson himself. Anti-Semitism was common in American universities on the eve of World War II, and while most of the best universities had one Jew or even two on their faculties of arts and sciences, to demonstrate that they were free of prejudice, none showed any willingness to appoint significant numbers until the flood of European émigrés after World War I began to open their doors.

MIT was able to recruit its charter faculty – Maurice Adelmam, Max Millikan, Eugene Rostow, Paul Rosenstein-Rodin, Solow, Evsey Domar and Franco Modigliani were Jews – “not only because of Samuelson’s growing renown,” writes Weintraub, “…but because the department and university were remarkably open to the hiring of Jewish faculty at a time when such hiring was just beginning to be possible at Ivy Leaguer Universities,”.

Many essays stand out. Backhouse nails down the details of Samuelson’s decision to sign on at MIT. Harro Maas, of Utrecht University, describes the efforts of the University of Chicago to lure Samuelson in the later 1940s. Perry Mehrling, of Barnard College, contributes a perspicacious essay describing the difficulty the MIT tradition, with its emphasis on the general equilibrium of a system of prices, had in coming to grips with the role of money, which the tradition customarily has abstracted away. And Beatrice Cherrier, of the University of Caen, provides a lively overview of the history of the department to begin the volume.

At one point Cherrier quotes a 1967 letter Solow wrote to his colleague Franklin Fisher, who had reported from Israel the view there that the MIT department is too committed to orthodoxy that Samuelson and Solow had devised to be able to recognize promising future developments, especially in theory. Solow wrote, “Peter Diamond and Peter Temin will help a lot. Miguel Sidrauski may develop very well…. The department has agreed to go for another econometrician, if we can find a young star. .. I think the prospects are good that we can remain the Duffy’s Tavern of economics, where the elite meet to eat.” The reference is to a popular radio show of the 1940s, an adumbration of the sentimental 1980s television series Cheers.

Fisher was right; Solow was wrong (though Cherrier doesn’t say so). Leadership in theory was about to pass from MIT, though its preeminence in applied economics would soon become apparent. But Solow’s metaphor is especially well chosen, and not just because of the gemütlichkeit of the customary table upstairs at the MIT faculty club, where the economists met most days for lunch.

The broadcast of Duffy’s Tavern always began the same way: a rendition of “When Irish Eyes are Smiling'' interrupted by the ringing of a phone: "Hello, Duffy's Tavern, where the elite meet to eat. Archie the manager speakin'. Duffy ain't here—oh, hello, Duffy."

The centerpierce of Transformation is an appreciation of Solow by Verena Halsmayer, of the University of Vienna. In “From Exploratory Modeling to Technical Expertise: Solow’s Growth Model as a Multipurpose Design,” Halsmayer makes a serious attempt to rescue Solow – the manager of the MIT economics department for 30 years – from the shadow of the brilliant Samuelson and evaluate the younger man’s principal contribution, the Solow model of economic growth.

It was a farther-reaching development than is generally understood, she argues, nothing less than a replicable “design” for a specific way of doing economics. a relatively unencumbered means of combining theory with measurement so as to interrogate the real world with “high hopes of producing useful and practical knowledge for economic governance.” As his student George Akerlof once put it, Solow began the process of turning the word “model” into a verb.

Transformation is the latest draft of history, a promising start on what promises to be a very complicated process. More will follow relatively quickly: Michael Weinstein, an MIT PhD who for many years was a member of the editorial board of The New York Times, is completing a book-length essay on Samuelson. Backhouse has begun a full-scale biography. Much more remains to be done including a proper biography of Solow.

Yet for all the value of careful history, it remains, by definition, a rear-view mirror That is why we have journalism, too.

David Warsh, a longtime economic historian and financial journalist, is proprietor of economicprincipals.com.

Col. Bacevich to speak on U.S. military actions abroad

Prof. Andrew Bacevich, a distinguished military historian, political scientist and retired Army colonel, will be speaking on American military interventions abroad at the meeting Thursday evening of the Providence Committee on Foreign Relations. With ISIS, Putin's invasion of Ukraine and Chinese expansionism in the South China Sea, it will be an interesting evening. Professor Bacevich is a well known skeptic about the utility of American military actions in such places as the Mideast.

Those great New England hurricanes of deep history

WOODS HOLE, Mass.

Intense hurricanes, possibly more powerful than any storms New England has experienced in recorded history, frequently pounded the region during the first millennium, from the peak of the Roman Empire into the height of the Middle Ages, according to a new study by the Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution (#whoi).

The findings could have implications for the intensity and frequency of hurricanes the United States could experience as ocean temperatures increase as a result of climate change, say study’s authors.

A new record of sediment deposits from Cape Cod show evidence that 23 severe hurricanes hit New England between the years 250 and 1150, the equivalent of a severe storm about once every 40 years. Many of these hurricanes were likely more intense than any that have hit the area in recorded history, according to the study. The prehistoric hurricanes were likely category 3 storms (Hurricane Katrina ) or category 4 storms (Hurricane Hugo) that would be catastrophic if they hit the region today, according to Jeff Donnelly, a WHOI scientist and the study’s lead author.

The study is the first to find evidence of historically unprecedented hurricane activity along the northern East Coast, Donnelly said. It also extends the hurricane record for the region by hundreds of years, back to the first century, he said.

“These records suggest that the pre-historical interval was unlike what we’ve seen in the last few hundred years,” Donnelly said.

The most powerful storm to hit Cape Cod in recent history was Hurricane Bob in 1991, a category 2 storm that was one of the costliest in New England history. Storms of that intensity have only reached the region three times since the 1600s, according to Donnelly.

The intense prehistoric hurricanes documented by the study were fueled in part by warmer sea surface temperatures in the Atlantic Ocean during the ancient period investigated in the study than have been the norm off the East Coast during the past few hundred years. However, as oceans temperatures have slowly inched upward in recent decades, the tropical North Atlantic sea surface has surpassed the warmth of prehistoric levels and is expected to warm further over the next century as the climate heats up, Donnelly said.

He said the new study could help scientists better predict the frequency and intensity of hurricanes that could hit the U.S. coast in the future.

“We hope this study broadens our sense of what is possible and what we should expect in a warmer climate,” Donnelly said. “We may need to begin planning for a category 3 hurricane landfall every decade or so rather than every 100 or 200 years. The risk may be much greater than we anticipated.”

Donnelly and his colleagues examined sediment deposits from Salt Pond in Falmouth. The pond is separated from the ocean by a 4.3- to 5.9-foot-high sand barrier. Over hundreds of years, strong hurricanes have deposited sediment over the barrier and into the pond, where it has remained undisturbed.

The researchers extracted 30-foot-deep sediment cores that they then analyzed in a laboratory. Similar to reading a tree ring to tell the age of a tree and the climate conditions that existed in a given year, scientists can read the sediment cores to tell when intense hurricanes occurred.

The study’s authors found evidence of 32 prehistoric hurricanes, along with the remains of three documented storms that occurred in 1991, 1675 and 1635.

The prehistoric sediments showed that there were two periods of elevated intense hurricane activity on Cape Cod — from 150 to 1150 and 1400 to 1675. The earlier period of powerful hurricane activity matched previous studies that found evidence of high hurricane activity during the same period in more southerly areas of the western North Atlantic Ocean basin, from the Caribbean to the Gulf Coast. The study suggests that many powerful storms spawned in the tropical Atlantic between 250 and 1150 also battered the East Coast.

The deposits revealed that these early storms were more frequent, and in some cases were likely more intense, than the most severe hurricanes Cape Cod has seen in historical times, including Hurricane Bob and a 1635 hurricane that generated a 20-foot storm surge, according to Donnelly.

High hurricane activity continued in the Caribbean and Gulf of Mexico until 1400, although there was a lull in hurricane activity during this time in New England, according to the study. A shift in hurricane activity in the North Atlantic occurred around 1400, when activity picked up from the Bahamas to New England until about 1675.

The periods of intense hurricanes uncovered by the new research were driven in part by intervals of warm sea surface temperatures that previous research has shown occurred during these time perio

Nicholas Corvino: Push innovation in psychologists' training

NEWTON, Mass.

We’ve heard the term “innovation” a lot lately. Boston’s Innovation District is booming. Life sciences and biotechnology companies throughout New England are creating innovative approaches to solve some of medicine’s most challenging problems. Companies across New England have “Chief Innovation Officers.”

The universities and colleges around New England are innovating daily. The tools, technology and research developed by these institutions will impact the world for generations to come. At the Massachusetts School of Professional Psychology (which is changing its name to William James College in May 2015) our faculty and staff also know of the importance of innovation. We practice a craft with more than 125 years of success, but our future will be bleak if we do not constantly think of new ways to prevent and treat mental illness.

Mental illness is a problem that many people don’t want to discuss, yet it affects all of us. Today, one in four adults and one in five children have a diagnosable mental illness, and one of two Americans will suffer from mental illness at some point in their lives. Suicide will claim one American every 13 minutes, and 12 times that number will make an attempt each day. When this problem strikes your family, and it is highly likely to, you might be among the 70% of parents in this country who cannot obtain care for your child.

These statistics are shocking, yet mental illness is a subject we talk about only after a terrible tragedy, or an act of violence. This should not be the case, as talking about and treating mental illness leads to tangible results. A good deal of research supports the efficacy of #psychotherapy. Up to 80 percent of the time, people who avail themselves of treatment will improve. That’s why our students spend about half of their time at William James College working in the field, learning their discipline from experienced professionals and encouraging people to open up about something that society has subtly suggested they should not talk about. However, with 50 percent of Americans likely to develop a mental illness in their lifetimes, we need to do more to start this conversation.

Mental-health professionals need to deliver information and care through electronic means. This involves embracing the latest tools and technologies available to them, and supplementing these technologies with the development of meaningful relationships with each patient. Technology alone cannot end the stigma associated with mental illness, but it can help to abate it.

At the same time, psychologists cannot be the only ones addressing mental illness. They are part of a multifaceted system. Teachers, medical practitioners and attorneys whose work touches the psychosocial lives of their students, patients and clients need to be educated to both attend to and intervene properly around emotional and behavioral issues that they see.

The future of mental-health care is not just in educating mental-health practitioners, but allied professionals to improve the quality of life of those affected by mental illness. These professionals are often the “first-responders” in a mental-health emergency. If they spot signs of mental illness early on, they can help the person suffering from mental illness to address the problems they face before they get out of control.

Conversations about mental illness should also be sensitive to our increasingly multicultural world. Students must be culturally informed and sensitive. Our role as innovators involves thinking about ways to meet the prevention and treatment needs of diverse populations. At William James College, faculty lead immersion trips to Haiti, Costa Rica and Ecuador each year to help students understand the mores, culture and health care system of diverse people. To talk about mental illness effectively, it is imperative to keep the diversity of the target audience in mind at all times.

Embracing experiential learning, having constant conversations about mental illness, educating colleagues in other professions, engaging technology, and encouraging a diverse approach to psychology education are concepts that our field has been slow to embrace. As innovators, we must champion these ideas, while also activating them.

I hope we can embrace the spirit of innovation and practical psychology that William James championed. William James was the founder of American psychology. He was an educator's educator, one of the century's greatest philosophers whose prolific writings and prodigious mentorship profoundly influenced the practice of applied psychology, experiential education, sociology and race relations in this country.

I think James would agree that psychology is about analyzing the past in order to look forward to a brighter future. If we all focus on innovating our field, our future conversations will revolve less around problems, and more on solutions.

Nicholas Covino is president of the Massachusetts School of Professional Psychology, in Newton, Mass., which will be renamed William James College in May 2015. This piece originated on the Web site of the New England Board of Higher Education (#nebhe.org).

Gentrifying fire traps

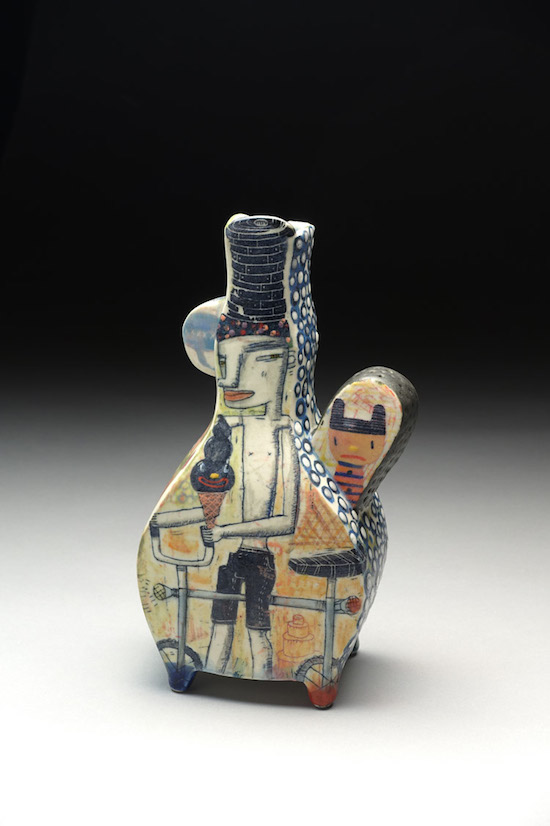

"Triple Decker'' (porcelain, glaze, underglaze, oxide wash), by KEVIN SNIPES, in the show "Human Moments: Ann Agee, Sana Musasama, Annabeth Rosen, Sally Saul, A&A and Kevin Snipes'' at Cade Tompkins Projects, Providence, on March 21-April 25.

"Triple Decker'' (porcelain, glaze, underglaze, oxide wash), by KEVIN SNIPES, in the show "Human Moments: Ann Agee, Sana Musasama, Annabeth Rosen, Sally Saul, A&A and Kevin Snipes'' at Cade Tompkins Projects, Providence, on March 21-April 25.

Of course, in this part of the country when we hear of "##triple-decker'' we think of those wooden, three-story, firetrap buildings in poorer sections of our cities and smaller mill towns. Back in the day when more people used space heaters, they often went up in flames, with death and injuries resulting. (I well remember the news reports of such fires virtually daily in the winter on WBZ radio, in Boston.)

The surviving three-deckers remain ugly, but in some gentrifying neighborhoods, especially in Boston, Yuppies have moved into them.

-- Robert Whitcomb

Linda Gasparello: ISIS's cultural devastation reaches new level

The ruins of Hatra

There is horror in the recent news that the Islamic State bulldozed the ruins of two of the greatest #assyrian cities #nimrud and #nineveh. And there is irony. These ancient cities, in what is now northern Iraq, were built by a ferocious people whose profession was war – people for whom the Hebrew prophets, including Isaiah, Nahum, Zechariah and Zephaniah, reserved some of their fiercest denunciations.

In the 9th Century B.C., Assurnasirpal II, a brutal militarist, erased entire nations as far as the coast of the Mediterranean Sea, stretching through what is now Syria, Lebanon and northern Israel. But he restored the ancient city of Nimrud and established his capital there. His magnificent Northwest Palace, first excavated by the British explorer Austen Henry Layard in the 1840s, was probably completed between 865 and 869 B.C. Its dedication was celebrated with a banquet for 70,000 guests.

Sennacherib, who moved the capital to Nineveh in 704 B.C., was as bellicose as his forefathers. When the city of #babylon rebelled against his despotic rule, Shennecherib destroyed it, saying, “ The city and its houses, from its foundation to its top, I destroyed, I devastated, I burned with fire. The wall and outer wall, temples and gods, temple towers of brick and earth, as many as there were, I razed and dumped them into the Arahtu canal.” But in Nineveh, he built a palace decorated with precious metals, alabaster and woods. Mountain streams were diverted to provide water for the city's parks and gardens, resplendent with trees and flowers imported from other lands – along with captives who were enslaved and brought back to Assyria to build and tend them.

It is a wonder that these Assyrian kings who were capable of such ruthlessness were also capable of building cities filled with such majestic architecture.

In the 1970s and 1980s, in the time of another ruthless leader, Saddam Hussein, the Iraqi antiquities board reconstructed large parts of Assurnasirpal II's palace, including the restoration and re-installation of the carved-stone reliefs lining the walls of many rooms, according to Augusta McMahon, a professor in the Department of Archaeology at the University of Cambridge.

“The winged bulls that guard the entrances to the most important rooms and courtyards were re-erected. The winged bull statues are among the most dramatic and easily recognized symbols of the Assyrian world,” McMahon wrote in a BBC report.

Nimrud, she added, “provided a rare opportunity for visitors to experience the buildings' scale and beauty in a way that is impossible to find in a museum context.”

That is lost for all of us, now and in future generations.

Fortunately, a significant number architectural artifacts from Nimrud and Nineveh are housed safely in museums in Europe and North America, including the limestone and alabaster reliefs, portraying Assurnasirpal II surrounded by winged demons, or hunting lions or waging war, and the monumental, human-headed winged lions that guarded important palace doorways, currently displayed in the British Museum in London and the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York.

As if the loss of Nimrud and Nineveh were not horrible enough for world heritage, #isis continued its campaign to eradicate ancient sites it says promote apostasy last week by leveling the ruined city of Hatra, also in northern Iraq, founded in the days of the Parthian Empire over 2,000 years ago. Hatra's massive walls withstood attacks by the Romans.

Irina Bolkova, director-general of UNESCO, said, “The destruction of Hatra marks a turning point in the appalling strategy of cultural cleansing underway in Iraq.”

I hope it does. And I hope that what Zephaniah prophesized for Assyria will befall the Islamic State: “Assyria will be made a desolation.”

Linda Gasparello (lgasparello@kingpublishing.com), is a longtime journalist and the co-host of “White House Chronicle,” on PBS. She was a master's candidate in Arabic and Islamic Art and Architecture at the American University in Cairo.

Government and job-creation

''Explanations exist; they have existed for all time; there is always a well-known solution to every human problem — neat, plausible, and wrong.''

-- H.L. Mencken

Again and again we hear the mantra from the likes of Tea Partiers that "government doesn't create jobs.''

Oh, yeah? Try starting and running a private business without roads and airports, without public education, without public health agencies, without the innumerable inventions of public-sector people working in the Defense Department (ever hear of the Internet?), the National Institutes of Health, etc., etc., etc.

Much of the anti-government mantra comes from folks in the Tea Party-dominated parts of the country in the South and the West that, interestingly, have the highest percentage of people depending on federal pork. And despite the Bible-thumping speeches that emanate from these places, they also in general have the highest rates of social pathologies, such as substance abuse and what we used to quaintly call "illegitimacy.''

Hypocrisy makes the world go round.

Sorry, but to have civilization you always need a "mixed economy'' of private business and the collective action known as ''government''. The ratio between them, as with tax rates, will frequently have to be adjusted to address the dangers of the excess power that one or the other will inevitably develop. The top federal tax rate, for example, was too high as Reagan took over. It was cut and the system was briefly simplified. (Since then, it has again been made even more complicated than before.)

Now, with, Putin, a cold and murderous gangster, running Russia, and collapsing U.S. physical infrastructure, the rates will probably have t0 be raised again. A matter of national security.

Most of us want simple answers to avoid doing the hard work of adjusting our processes and practices to changing reality. But as J.P. Morgan once said after being asked what the stock market would do: "It will fluctuate.''

Coastal treasure in steel

"Eelgrass Dancing'' (steel and lacquer), by K. GRETCHEN GREENE, in her show at Artisan's Asylum, Somerville, Mass., May 21-June 4.

"Eelgrass Dancing'' (steel and lacquer), by K. GRETCHEN GREENE, in her show at Artisan's Asylum, Somerville, Mass., May 21-June 4.

Eelgrass, by the way, is a salt-water plant essential for the survival of many coastal animal species -- including many that we eat -- in New England. Far too much of it has been destroyed by man-made pollution and coastal development. Public and private groups have made efforts to restore eelgrass beds in some places, such as Narragansett and Buzzards bays.

Robert Whitcomb: Film tax credits, stadiums and 'mud season'

Massachusetts Gov. Charles Baker wisely proposes to end that state’s film/TV-production tax credits. Perhaps it will get more Rhode Islanders thinking about such dubious projects as what I call 38 Studios Memorial Stadium, proposed for downtown Providence. (Readers would do well to read the March 9 Wall Street Journal article “Pro Stadiums, Public Money’’.)

In lieu of the gift to film and TV producers, Mr. Baker wants to expand the state’s earned-income tax credit, which helps poor people. That’s broad enough policy to perhaps help the economy of all of southern New England.

The Massachusetts film/TV tax credit goes back to 2005, when movie star and Massachusetts native Matt Damon pushed the idea. Legislators and then-Gov. Mitt Romney put in a law in that made film-and-TV-production companies eligible for sales, income and corporate-excise-tax credits. The giveaways were expanded in 2007 under then-Gov. Deval Patrick.

The math never added up for the state, much as politicians and others loved being photographed with movie stars and Boston gossip columnists loved writing about them. And, yes, it’s been nice for a few show-biz folks actually based in Massachusetts – while keeping money from people in other sectors and from, for example, MBTA repair.

Robert Tannenwald, a former Federal Reserve Bank of Boston economist who now teaches at Brandeis, analyzing state Department of Revenue data, told The Boston Globe that ‘’each full-time-equivalent job created by the credits and filled by residents has cost the commonwealth $118,000 in foregone revenue. For each dollar of foregone revenue, Bay Staters have earned only 53 cents in additional income.’’

And The Globe’s Joan Vennochi noted (“Good riddance to the Mass. film tax credit,’’ March 8): “{O}nly about one-third of the $304 million in spending generated by the tax credit{s}was spent in Massachusetts; and of nearly 2,000 jobs created by the tax credit{s}, only about one-third went to Massachusetts residents.’’

I think of film and pro-sports stadium scams when I drive around Rhode Island, with its Third World roads, crumbling bridges, decayed public buildings and other signs of infrastructure decline.

Those promoting special deals for favored individuals and businesses depend on the public not doing the macro-economic math. The fun for the favored few has to be made up in taxes paid by the unfavored and by not maintaining services and infrastructure used by everyone, thus hurting the economies of the jurisdictions handing them out.

Massachusetts and Rhode Island should focus on creating a fair, simple and transparent tax systems and on investing in physical infrastructure and services that help as many people as possible, not sexy economic special-interest groups and celebrity ego trips.

With the states’ superb location for doing business in the international market, famous educational institutions that directly and indirectly churn out technological innovations, and natural and manmade beauty, they can succeed without handing out special deals. Let the rich build the likes of stadiums entirely with their own money.

xxx

With the snowpack slowly melting, I recall this from Alan H. Olmstead’s book “In Praise of Seasons’’ about winter’s end, desired more than usual this year:

“Addicted to the thermometer, we are precariously indifferent to other standards for living. The fire stands off the ice; we run the season’s gauntlet between them, one half of us always a little too warm, the other on the verge of being too cold. We come near the end of our passage without much feeling of any kind, a surly numbness with the world as we would never have made it.’’

New England’s ''mud season'' is much maligned, but the prospect of softness underfoot, even a squishy softness, is happy. Finally, we’ll see the ground, the mud will dry out and the brown will change to green to soothe us for weeks, until we all too quickly take it for granted.

As Mr. Olmstead wrote:

“When, at last, spring starts to emerge, we know it first by a restoration of respect for things about us, a rebirth of loyalty to life, a softening of our partisan judgments, an ending of our harsh loneliness.’’ Briefly.

Robert Whitcomb (rwhitcomb51@gmail.com), overseer of this site, is a partner in Cambridge Management Group (cmg625.com), a health-care sector consultancy, and a Fellow of the Pell Center for International Relations and Public Policy. He's also a former finance editor of the International Herald Tribune and former editorial-page editor of The Providence Journal.

Back home, under wraps

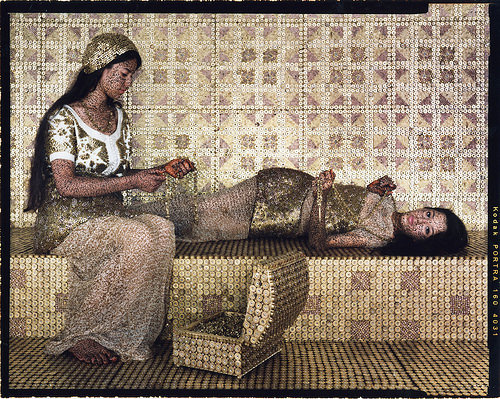

"Bullets Revisited #8'' (C-41 photographic print mounted on aluminum), by LALLA ESSAYDI, in the show "Beyond the Veil,'' at the University of Massachusetts at Lowell, through March 20.

The gallery says the show "explores the complexities of Arab female identity, both from an insider's experience of her own Moroccan childhood, and with the outsider perspective of a Western-trained artist.''

The pictures are part of a "collaborative performance project that takes place in her childhood home in Morocco with female friends and family members.''

"{T}hese women use calligraphy, bullet casings, henna, their bodies and their gaze to subvert traditional and imposed notions of gender, ethnicity and identity.''

She's lucky to have escaped, at least in part, Arab culture, with its often horrendous treatment of women and of members of other religions faced with the brutal bigotry of some versions of Islam. She now lives relatively safely in the U.S., away from 7th Century ideas of women's place in the world.

Our own speed trap; arrogant SUV'ers

The stories about the Ferguson, Mo., police using big fines from trivial traffic violations, especially against African-American drivers (who are, it is true, a majority in that city), as a major municipal revenue source sounds like a variant of some communities in New England. East Providence, R.I., is one of those "speed traps'' that works very hard to get as much revenue as it can from hapless drivers who find themselves into that confusing labyrinth, with its notoriously bad signage. Some forward-looking drivers might want to avoid that burg entirely.

xxx

What is it about the arrogance of SUV drivers that makes them speed through streets narrowed by snow banks and push everyone else aside -- people in normal cars as well as pedestrians?

Is it because they're sitting so high above the street and that they think they can use the sheer size of their hideous gas-guzzlers to force everyone else off the road? Or do they think they're better than other drivers because they have been able to afford one of these disgusting vehicles?

And they're even worse at night because SUV's have blinding lights. Where is the National Transportation Safety Administration when we need them? But wait a minute. A lot of lobbyists have these things.

--- Robert Whitcomb

Chris Powell: Conn. losing a casino war it started

|

||

|

|

||

Don Pesci: Three steps to fix Connecticut

Eleanor Schwartz Greco: Inhofe and other capital weather wimps

Coming up next in Washington.

What’s wrong with Washington?

I’m not talking about goofy political antics, like James Inhofe’s latest bid to disprove climate change.

In case you missed it, the chairman of the Senate’s Environment and Public Works Committee gave a mind-numbing speech a few weeks ago in which he muttered about February’s “unseasonal” weather, ice ages, polar bears, and terrorism.

At the start of the Oklahoma Republican’s 22-minute ramble, he slipped a snowball from a Ziploc bag and tossed it from his Senate floor perch. Mashing together weather and climate, Inhofe said the Earth can’t possibly be getting any warmer if it still snows in our nation’s capital.

Even Fox News Radio taunted the nation’s most prominent climate denier about this stunt, quoting from one of his books and running the headline “James Inhofe: There Is No Global Warming Because God.”

Money, actually, powers this delusion. Fat contributions from oil, gas, coal, and utility companies explain why politicians like Inhofe are still ignoring the overwhelmingconsensus among scientists that makes addressing climate change a top priority.

What I don’t get is why the 6 million people who make their homes in the District of Columbia and its suburbs cower whenever winter does its thing. No lobby fuels that.

Entire school systems in the nation’s seventh-biggest metropolitan region may open late or close altogether because of botched snow forecasts followed by slushy streets. The Metro system slows down and trains can’t service all stations when rail lines ice over. Garbage piles up and accidents clog the roads when it snows.

After living here for nearly 20 years, I’m never surprised when temperatures dip below the freezing point between November and March. Or when snowflakes flutter from the sky. I realize that snowdrifts bury cars and skim the bottoms of stop signs once every five years or so.

That’s why the whimpers irk me as much as the area’s systemic failure to hack winter weather. On crowded elevators, I struggle not to blurt “This isn’t Florida: Bundle up or shut up” at complainers who won’t wear a hat, a scarf, gloves, or a good pair of boots.

If they would just stop whining, these folks might take advantage of the freedom cold bouts bestow upon you to sleep in, cradle a good book, or cook up a storm.

I live in Arlington, Va. It’s the nation’s most-educated county, but lately my second-grader and third-grader haven’t spent much time with their teachers. During the first week of March, the local authorities shut schools on a snowy Monday, whittling a three-day week to just two days of instruction.

You see, the school system had already canceled all Thursday and Friday classes to give the parents of kids in elementary school time to meet with teachers. When it snowed again, Arlington Public Schools locked us out, too.

My family made the most of winter’s final blast by heading to Davis, W.Va., for two days. We cross-country skied, slid down North America’s longest sled run, and stomped around in the sparkling snow.

Spring snuck into town before we returned.

The cherry blossoms will bloom soon. All that pink will cheer up Washington’s wimps for a while. Then they’ll start fretting about the summer heat.

Yogurt, or psycho-ceramics?

"Composition of Enclosed Cylinders,'' by LAUREN MABRY, in the show "A Ceramic Spectrum,'' at New Art Center, Newton, Mass., March 22-May 9.

The gallery's notes say:

"Mabry's cycliners and curved planes create a 'still' canvas for her Abstract-Expressionist glaze experiments, which flow and co-mingle when fired in the kiln.''