Via ecoRI.org

There’s an estimated 5.25 trillion pieces of plastic debris in the world’s oceans. Some 8 million tons of plastic enter the sea annually. How much is floating in local marine waters remains a mystery. An answer may be forthcoming, though, as researchers will spend five days next week scouring Narragansett Bay for plastic.

The July 18-22 trash trawl is being conducted by the Rhode Island chapter of Clean Water Action (CWA) to raise public awareness about the most invasive “species” in the ocean: plastic.

Johnathan Berard, state director of CWA Rhode Island, was the policy director at Blue Water Baltimore when the organization partnered with Trash Free Maryland a few years ago to conduct a similar trawl of Chesapeake Bay. While the amount of visible plastic collected was “striking,” the four-day effort also captured a “great deal” of micoplastics — likely photodegraded pieces of plastic bags and wrappers — fishing line, and cellophane rip-strips from cigarette packs.

The Chesapeake Bay trawl and a similar one done on the Hudson River were for scientific research. The Narragansett Bay trawl is more of an advocacy project.

“We want to get elected officials, the press and advocates face to face with the problem,” Berard said. “A jar of Narragansett Bay water filled with plastic is a powerful image.”

Next week’s five-day sweep will employ an ultra-fine mesh net designed to capture micorplastics, microbeads and micofibers. These tiny plastic particles represent the planet’s next big environmental and public-health concern.

Microfibers from polyester fleeces and other synthetic clothing are an emerging concern when it comes to the quality of drinking water. Neither washers nor wastewater treatment facilities are designed to remove these accumulating bits of plastic.

“We can’t keep pushing plastic into the economy,” Berard said. “It wreaks havoc once it’s out in the environment. We find this stuff in our water. It’s in the fish we eat. On our beaches. It’s going to get to a point when it will be too gross to go to the beach or eat fish.”

Plastic packaging isn’t well recycled, or reused. (As You Sow)

Throwaway Economy

The United States alone tosses out 25 billion Styrofoam cups annually, more than 300 million straws daily, and some 3 million plastic bottles every hour of every day. Few of these items are recycled or reused.

“The current system pumps tons of plastic into the economy and environment,” said Jamie Rhodes, program director for UPSTREAM. “The scope of the problem is huge. We can’t burn or recycle our way out of this problem.”

Southern New England is certainly home to its share of plastic pollution. But how much? No one ecoRI News spoke with for this story has any idea, and while they all would be interested in finding out, their bigger concern is how to lessen the local impact of a global problem.

But, as Rhodes, former chairman of the Environmental Council of Rhode Island, noted, we can’t simply ban plastic. “Plastic has raised people out of poverty. I, for one, don’t want a computer made of iron,” he said. “But it’s overused. We need to use it more wisely.”

What is considered a “wise use,” however, can be subjective. One person might think wrapping a cucumber or apple in plastic is a ridiculous waste of resources and feeds the growing waste stream. Another person might argue that such a use of plastic prolongs shelf life and reduces organic waste.

What can’t be debated is the amount of plastic litter collected at beach cleanups in Connecticut, Massachusetts and Rhode Island, roadside debris seen through moving windows, and the flotsam and jetsam that bob in the region’s waters.

“Plastics suck in chemicals. That’s what they’re good at,” Rhodes said. “What’s the long-term impact on humans, on the environment?”

Dave McLaughlin, executive director of Middletown, R.I.-based Clean Ocean Access, noted that “we don’t know the implications of the bioaccumulation of plastics in humans.”

“They’re endocrine disruptors and that is some scary stuff,” he said. “It’s important that we understand the severity of the issue.”

Plastic bags float in Buzzards Bay, Long Island Sound and Narragansett Bay like jellyfish. Turtles, whales and other marine animals often mistake them for food, causing many to starve or choke to death. In fact, all of southern New England’s fresh and salt waters, from hidden brooks to popular beaches, are touched by plastic — a toxic problem that threatens wildlife and public health.

Adult seabirds inadvertently feed small pieces of plastic to their chicks, often causing them to die when their stomachs become filled with petroleum byproducts. As plastic breaks down into smaller fragments — microplastics that may contain toxic chemicals as part of their original plastic material or adsorbed environmental contaminants such as PCBs — fish and shellfish become increasingly vulnerable to the toxins these polluted particles collect.

At least two-thirds of the world’s fish stocks are suffering from plastic ingestion, according to estimates, as much of the planet’s plastic pollution eventually makes its way into the ocean. Local seafood favorites such as stripers and quahogs, for example, are vital to southern New England’s marine food web and the region’s economy.

The countless plastic bags, plastic bottles and plastic wrap strewn along southern New England’s coastline, swimming in the region’s rivers, ponds and lakes, waving from trees, and loitering in parks were each likely used only once, and for just a few minutes. These petroleum byproducts, however, don’t biodegrade. They remain in the environment for centuries. Their long-term impact on environmental and public health is not yet fully understood, and barely studied.

“We’ve plasticized the entire biosphere, including our bodies,” Marcus Eriksen, research director and co-founder of the 5 Gyres Institute, said during a March panel discussion at Brown University titled “The Plastic Ocean.” “The impact of plastic is widespread.”

The world’s plastic problem was first acknowledged in the 1970s. A 1973 survey of the plastic materials accumulating on a private beach on Conanicut Island in Narragansett Bay, for instance, found that the plastic pollutants “were mainly a by-product of recreational activities within the bay and not household, industrial or agricultural refuse.”

The study also noted that “plastic objects manufactured from polyethylene made up the bulk of the flotsam on the beach.” Among the plastic items collected were milk-shake tops, beer-can carriers, fish-hook bags, straws, bleach containers and shotgun pellet holders.

In 1987, the United States eventually responded to the growing plastic problem, with the passage of the Marine Plastic Pollution Research and Control Act. The law, which went to effect Dec. 31, 1988, made it illegal for any U.S. vessel or land-based operation to dispose of plastics in the ocean.

However, this act and other laws like it, such as the Microbead-Free Waters Act of 2015, can’t compete with mass consumption in a throwaway society. Their effectiveness is further limited by Washington, D.C.’s relentless assault on environmental protections, and by non-existent or lax waste-management practices in much of Southeast Asia and in developing countries.

Some four decades since the problems associated with plastic manufacturing and use were first identified, apathy, ignorance, convenience and profit have led to an addiction that is trashing the planet and putting human health at risk.

While our plastic reliance, especially for single-use items, grows, the reuse and recycling of this material has essentially flatlined. Waste-management practices can’t keep pace with the volume of production and the relentless tidal wave of new plastic packaging.

Currently, less than 15 percent of plastics packaging is recycled worldwide, according to As You Sow, a nonprofit foundation chartered to promote corporate social responsibility.

As You Sow is one of about 800 organizations worldwide, including UPSTREAM and the Story of Stuff, united in the goal of dramatically reducing the production of single-use plastic packaging, containers and bags. It’s known as the Break Free From Plastic movement.

Since most plastic is made from fossil fuels, the issue of plastic manufacturing, use and waste is also one of climate change.

“It’s fuel early on, a kid’s juice pouch in the middle, and a fuel at the end,” UPSTREAM’s Rhodes said.

Litter, especially of the plastic variety, costs taxpayers plenty. (Frank Carini/ecoRI News)

Local Impact

Plastic pollution doesn’t just ruin beach getaways and picnics in the park. It also harms the limited exposure many urban children have to nature, according to Leah Bamberger, Providence’s sustainability director.

Last year, the city had a study done to better understand how Providence residents, most notably children, perceive nature and how they use the city’s parks and open spaces. The study found that among the main concerns of children and their parents was the cleanliness of outdoor spaces, particularly litter in parks.

“Litter was the number one barrier that kept kids from enjoying nature and our parks,” Bamberger said. “It debunked the myth that urban kids don’t care about nature.”

Dealing with the region’s litter problem, much of which is some form of plastic, requires taxpayer funding and the ample use of unpaid time.

Staff and volunteers of Clean Ocean Access (COA) have spent the past 11 years cleaning up the Aquidneck Island shoreline. In that time, volunteers have worked nearly 14,000 hours and picked up some 95,000 pounds of debris, much of it plastic, according to McLaughlin, the nonprofit’s executive director.

“There’s litter that’s preventable — the stuff that blows out the back of pickup trucks — and then there’s illegal dumping that’s intentional,” he said. “Most of the plastic we find is from the society of convenience, like packaging and single-use items. A small piece of plastic has a pretty big impact.”

Of the 94,487 pounds of debris collected during 457 cleanups held between 2006 and 2016, much of it was plastic-based, such as bottles, food wrappers, fishing line, straws and cigarette filters, according to the 10-year anniversary report released by COA earlier this year.

All those cigarette butts nonchalantly flicked from car windows and haphazardly dropped on the ground, along with tobacco packaging and plastic lighters, represent one of the main sources of marine debris worldwide. Cigarette butts are made from a plastic called cellulose acetate. It doesn't biodegrade, and can persist in the environment for a long time. This plastic also contains toxins that can leech into water and soil, harming plants and wildlife.

On World Oceans Day, June 8, COA held a coastal cleanup at Easton’s Beach in Newport. Seventy-two volunteers collected 160 pounds of debris, including 1,700 cigarette butts.

Unsurprisingly, plastic bags also make up a good chunk of the organization’s shoreline hauls. Between 2013 and 2016, for example, volunteers picked up 11,874 bags.

The Aquidneck Island coastline, however, isn’t the sole domain for litter. The waters off Newport, Middletown and Portsmouth are also teaming with debris, most notably Newport Harbor. The Rozalia Project has documented a concentration of trash in the historic harbor at 41 million pieces of litter per square kilometer. Trash covers 25.2 percent of the harbor’s seafloor. It’s been dubbed Beer Can Reef, although much of the debris is plastic bottles and cups.

The Long Island Sound Study notes that marine debris is a nuisance and hazard for boaters. For instance, floating lines can foul a boat’s propellers, and chunks of plastic or plastic bags can block an engine’s cooling-water intake.

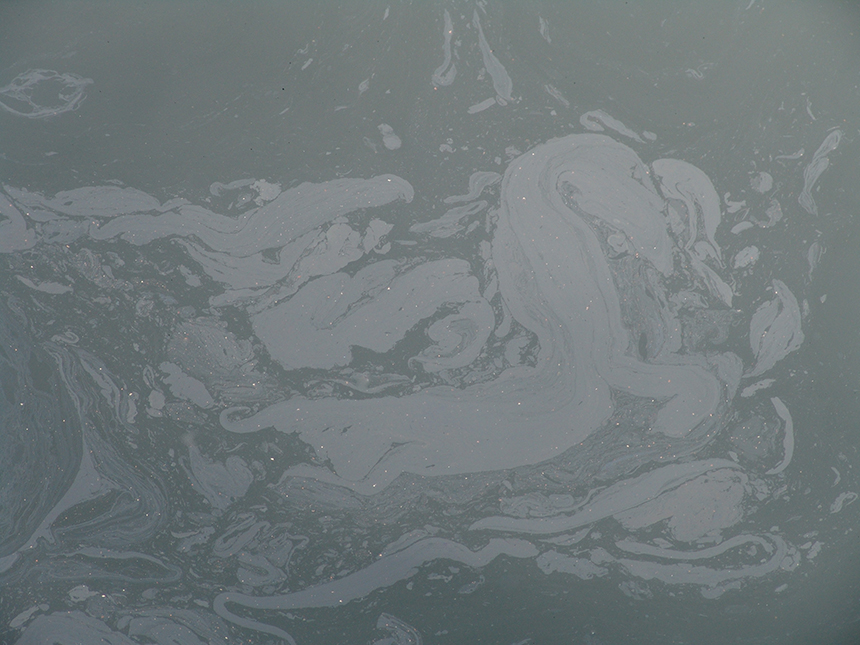

“While floatable debris in the open waters of Long Island Sound is less concentrated than in the neighboring New York-New Jersey Harbor estuary and in western Long Island Sound embayments, it is present in great enough quantities to mar the aesthetic enjoyment of the Sound,” according to the program that was started in 1985 by the Environmental Protection Agency and the states of New York and Connecticut to improve and protect the water quality of Long Island Sound. “Debris floating in the waters of the Sound can accumulate along with detached seaweed and marsh grass into large surface ‘slicks.’ These slicks can wash ashore fouling beaches and the coastline.”

Plastic caught in fences, lying on beaches, blowing around open spaces and carried by stormwater runoff into the region’s sensitive estuaries is much more than an eyesore. It’s pollution, and it has economic, ecological and public-health impacts. It’s a macro-, micro- and nano-scale problem.

To get a rough idea of the amount of litter accumulating in Rhode Island, McLaughlin did some conservative guesstimating. He figured if 5 percent of the state’s 1 million residents littered once a month, accidental or not, Rhode Island would see 600,000 new pieces of wind-blown trash annually. If 5 percent of the Ocean State’s 3.5 million annual visitors did the same, another 2.1 million pieces would be added to the landscape.

Collectively, southern New England taxpayers spend millions of dollars annually to clean up and prevent litter, much of which is of the plastic variety. Providence and other cities have to spend time and money notifying businesses to keep their Dumpsters closed, so trash doesn’t blow away or get spread about town by animals. DPWs have to clean vacant lots of trash and clear clogged storm drains and catch basins.

It also costs taxpayers when loads of municipal recycling are contaminated — plastic bags are one of the biggest contaminators; biodegradable and compostable plastics are also problem contaminants — and the collected material must then be buried or burned, instead of sold to recyclers.

Despite her relentless efforts organizing cleanups, Massachusetts resident Bonne Combs says, ‘We can’t clean our way out of this problem.’ (Courtesy photo)

No one pays Bonnie Combs to pick up after others. The Blackstone, Mass., resident is a relentless reuser and recycler. She conducts daily one-woman cleanups, at Stump Pond in Smithfield, R.I., up and down the banks of the Blackstone River and in her neighborhood, to name just a few spots. She founded Bird Brain Designs by Bonnie to repurpose animal feed bags into reusable shopping bags.

The marketing director for the Blackstone Heritage Corridor (BHC) manages the organization’s Trash Responsibly program. She also started the BHC’s Fish Responsiblyprogram, which works with businesses, such as Ocean State Tackle in Providence and Barry’s Bait & Tackle in Worcester, and the Audubon Society to make sure monofilament fishing line and spools are recycled properly.

Combs regularly sees firsthand the pervasiveness of southern New England’s plastic problem. She said nips are a “huge problem.” She picks up plenty of iced-coffee cups wrapped in both Styrofoam and plastic, and sees discarded plastic packaging everywhere.

“It’s becoming harder and harder to buy everyday products in recyclable packaging. It’s really frightening,” Combs said. “We have a waste problem. We need to go on a waste diet.”

Since this month is Plastic Free July, perhaps southern New England should start dieting now. But dieting is hard. Much of the world’s food and drink, from coffee to baby food, is now wrapped and shipped in plastic.

Addressing the region’s plastic problem, however, is complicated and will require more than avoiding plastic utensils, plastic bags, plastic water bottles, plastic straws and mylar balloons for a month. McLaughlin, of Clean Ocean Access, said the issue demands a three-pronged approach: policy, which he called “the stick;” technology/innovation, “business taking the lead;” and engagement, “the carrot.”

McLaughlin believes, at this moment at least, all three legs are a little too short.

“It starts with people becoming educated, connected and stewards of the environment,” he said. “We just can’t ban our way to a healthy ocean.”

Policy Improvements

Since the late 1960s, plastic shopping bags have been clogging storm drains, degrading marine ecosystems, choking animals, littering beaches and leaching estrogenic chemicals, but the Ocean State and its two southern New England neighbors lack the political will to enact statewide bans. The American Chemistry Council, the American Petroleum Institute and other lobbyists hold more sway than in-your-face environmental degradation and public-health concerns.

The environmental/public-health impacts associated with plastic manufacturing and disposal include greenhouse-gas emissions, and water and land pollution. For instance, a billion discarded plastic bags is the equivalent of 12 million barrels of oil. These costs are largely ignored.

Lobbyists from D.C. and parts unknown descend whenever a statewide ban or local one is discussed in Connecticut, Massachusetts or Rhode Island. They argue that consumers benefit from the use of plastic bags, because they can easily carry goods without the burden of lugging around reusable bags. They note that plastic bags handed out by retailers are reused as pet-waste containers or to line household trash receptacles. They say properly collected and recycled plastic bags — they shouldn’t be placed in curbside recycling bins and instead be brought back to stores for collection — are made into a composite product used as a wood substitute for decks and stairs.

Unfortunately, only a small percentage of plastic bags are actually recycled. In Rhode Island alone, some 190 million plastic bags are consumed annually, according to a 2006 Brown University study, and only about 9 percent are recycled.

Lobbyists, however, have failed to sway some local municipalities. Three Rhode Island communities — Barrington, Middletown and Newport — have passed bans on plastic retail bags. About 35 municipalities in Massachusetts have similar bans. The first municipality in New England to ban plastic checkout bags was Westport, Conn., in 2008.

While lawmakers in southern New England’s three states have been slow to adequately address the region’s role in the world’s plastic problem, a few western states have attempted to change the paradigm. California enacted a statewide plastic-bag ban last year, despite intense lobbying by plastics manufacturers. A 2013 study of San Jose’s bag ban helped pave the way for California’s statewide ban. The study found that after San Jose enacted its bag ban, there was nearly 90 percent less plastic debris in the city’s storm drains and about 60 percent less plastic street litter.

In Hawaii, all four of the state’s county councils and the city of Honolulu have passed some type of bag ordinance that has effectively banned plastic retail bags in the 50th state.SThis year, Connecticut debated a proposal to put a 5-cent tax on single-use plastic and paper shopping bags. The city of Providence has warned and then fined residents who continue to use their recycling bins for trash. On June 22, for example, the city’s five enforcement officers wrote 50 tickets.

McLaughlin, of Clean Ocean Access, noted that states and municipalities need to support, fund and enforce waste-diversion efforts. In Rhode Island, at least at the state level, resources for such efforts are scarce. In the three decades since the state’s recycling law was enacted, the Rhode Island Department of Environmental Management has neither warned nor fined any business for noncompliance.

Bag bans, bag taxes, fines and enforcement, while all part of the solution puzzle, aren’t the key pieces. Producer responsibility, also known as product stewardship, enlists manufactures in the disposal and recycling of the hazardous and bulky goods they produce. In southern New England, producer-responsibility programs already exist for mercury thermometers and thermostats, paint, and mattresses.

Bamberger, Providence’s sustainability director, Rhodes, of UPSTREAM, and CWA’s Berard all told ecoRI News that producer responsibility is vital to local, national and global efforts to reduce plastic pollution, minimize packaging and change practices.

“Bans are nice, but they’re not a good solution,” Bamberger said. “Producer responsibility is the most effective way to manage the waste stream.”

Berard said, “Manufacturers can’t just put all this material into the economy and then have no skin in the game post-use.”

One of UPSTREAM’S focus points is helping make producers more responsible, here and across the globe.

“Companies need to be part of the solution,” Rhodes said. “We need policies to stop the flow of single-use plastic. This isn’t the system we’ve always had. We created it; we can change it.”

Innovation and Technology

They look like small, floating Dumpsters. In their first year of use, the two trash skimmers attached to docks at Perrotti Park removed more than 6,000 pounds of debris from Newport Harbor. Much of the litter was of the usual-suspect variety — plastic food wrappers, straws and bags, and fishing line.

COA’s Newport Harbor Trash Skimmer Projectwas implemented last August, and made possible by funding from 11th Hour Racing. Some 30 units, manufactured by Washington-based Marina Trash Skimmers, are in use on the West Coast and Hawaii. The two installed in Newport Harbor are believed to be the first ones in use on the East Coast.

They operate essentially as large pool skimmers, filtering water 24 hours a day and capturing floating debris and absorbing surface oil or other contaminants. The skimmers are powered by a three-fourths-horsepower electric engine that costs $2 a day to run. Hundreds of gallons of water flow through the units every few hours, and the skimmers are minimally invasive to marine life.

COA has since added a trash skimmer at Fort Adams State Park and at New England Boatworks, in Portsmouth.

“These units are highly effective in removing floating marine debris,” COA’s McLaughlin said. “But we can’t put trash skimmers everywhere.”

A similar piece of equipment in use in Baltimore’s Inner Harbor also removes debris, including plastic litter, from the water. The water-powered wheel deposits the scooped-out trash into a Dumpster. When there isn’t enough water current, a solar panel attached to the unit provides additional power.

New technology, whether it’s floating Dumpsters or trashy water wheels, play a role in controlling litter. To better address plastic manufacturing and use, however, advanced packaging innovations will have to play a bigger role.

Public Engagement

Solving the problem of plastic pollution can’t be done by stopping littering and improving recycling rates. Producer responsibility alone won’t end the deluge. The effort must include education and outreach, to curb such issues as “wishful recycling.” It’s also about changing behaviors — something as simple as restaurants asking if you want a straw rather than just giving you one.

According to a study recently done by UPSTREAM for the city of Providence, one way to address the issue at an individual consumer level is to incentivize behavior to reduce single-use items, such as being allowed to cut the line at the coffee shop if you bring your own mug.

Much of the outreach is needed to make people aware that the region’s plastic problem isn’t magically fixed curbside, or at a transfer station, landfill or incinerator.

“We see litter on the streets and plastics in the ocean, but when we put our recycling out at the curb, we don’t care or know what happens next,” Rhodes said. “Much of the this material is shipped to small, developing countries like the Philippines and Malaysia, where poor waste pickers go through it.”

McLaughlin said the overuse of plastic is a solvable problem. He said it starts with individuals taking action.

“We have to take care of each other and the environment. That’s how we are going to make progress,” McLaughlinsaid. “We have to get people involved at the local level to take action."

Frank Carini is editor of ecoRI News.