Charles F. Desmond: COVID-19 crisis displays 'The Amazing Generation'

— Photo by Artur Bergman

From The New England Journal of Higher Education, a service of The New England Board of Higher Education (nebhe.org)

BOSTON

As a nation, we are taught to understand that it is sometimes necessary to send soldiers into harm’s way to fight for values and principles that we believe are worth sacrificing for. Today, and throughout our history as a nation, young men and women have been called upon to fight in foreign lands for the advancement of democracy and to secure and preserve the religious rights and political freedoms of marginalized groups and disenfranchised individuals.

I am a decorated veteran of the unpopular war in Vietnam. I went to war believing in the aforementioned values and principles. Over the many years that have passed since then, I have on occasion questioned whether my military service mattered, whether the suffering, destruction and loss I saw on the battlefield served a larger purpose, or whether anything of value in America was derived from the loss of treasure and human sacrifices made in that war’s name.

Over the past month, I have watched the deadly march of the COVID-19 virus from across the world and onto our nation’s shores. The human toll wrought by the virus has now exceeded 22,000 in the U.S. Coupled with this dreadful loss of human life, the economic and social upheaval the virus has rendered is beyond anything we have witnessed in recent history.

In the face of this human suffering and social upheaval, we are witnessing across the country, I have been heartened and inspired by the selfless and heroic actions of our younger generation of Americans. Any doubts I had about what American stands for or how we as a nation care for and support each other have been answered. One need only read the daily newspaper or turn to any television station and you will see thousands of young Americans who have put themselves into harm’s way in their battle to do whatever is necessary to defeat this virus.

I see a generation who were not drafted and who did not enlist to serve in this war but who have stepped forward in cities and towns, hospitals and schools and everywhere else where they are needed in the national campaign to eradicate this virus from our country. I have watched in wonder and pride as doctors, nurses, researchers, emergency medical personnel, police, fire and military service members, truck drivers and grocery store cashiers who all have put their personal and family safety aside and, under unimaginable conditions, fearlessly faced this horrific disease in an effort to serve, support and save their fellow Americans who, without them, would surely fall victim to a virus that does not discriminate by race, color, age or economic status.

The generation that fought in World War II much later came to be called The Greatest Generation. Some scholars and pundits have written that that generation may have been America’s greatest. I do not agree. I believe we are now witnessing the emergence of a new generation of Americans that cannot be called anything other than “The Amazing Generation. ” If their actions and behaviors now are any indicator, America is now and will continue to be in good hands.

Charles F. Desmond is CEO of Inversant, the largest parent-centered children’s saving account initiative in the Massachusetts. He is past chairman of the Massachusetts Board of Higher Education (NEBHE) and since 2011, has served as a NEBHE senior fellow.

Emily P. Crowley/Robert M. Kaitz: N.E. colleges must consider labor laws in the pandemic

College lecture halls are now empty.

— Photo by ChristianSchd

From The New England Journal of Higher Education, a service of The New England Board of Higher Education (nebhe.org)

BOSTON

As COVID-19 rapidly changes the economic landscape throughout the country, higher education institutions (HEIs) are facing new, constantly evolving challenges. To address these challenges, federal and state governments are quickly drafting laws and regulations that are impacting colleges and universities, and their employees.

Wage and hour challenges

As HEIs grapple with COVID-19 fallout, including the cancellation of in-person courses, commencements, freshman orientations and other events in the upcoming months, they must remain cognizant of existing wage and hour laws when rolling out reductions in hours or furloughs for employees due to the diminished workload. Under the Fair Labor Standards Act (FLSA), employers need to pay only non-exempt, hourly employees for actual time worked, rather than for time employees are regularly scheduled to work. As a result, reduced-hour schedules or unpaid furloughs are relatively straightforward for these employees, with institutions obligated to compensate them for all hours worked, and nothing beyond that. Perhaps due to public relations concerns, some HEIs have gone beyond their obligations by continuing to pay employees who can neither come to work nor work remotely. Harvard initially offered full pay and benefits for 30 days to direct employees who could not work in light of the campus closure. But in the face of a social media campaign and other negative press, Harvard agreed to provide paid leave and benefits through May 28, 2020, to all direct employees, plus subcontractors. Many schools have enacted similar policies.

Unlike hourly, non-exempt employees, a reduction in hours or furlough may have significant ramifications for exempt, salaried employees. The FLSA exempts these “white collar” salaried employees from overtime premium pay, as their salary is considered remuneration for all hours worked in a week, whether more or less than 40 hours. As a result, employers must pay exempt employees their full week’s salary if they perform any work during that workweek, including work from home. This remains true even while an employee is on furlough, so colleges and universities must communicate clearly to all exempt employees that they cannot perform any work while on furlough—even small tasks like sending work emails—without prior written approval of a supervisor, because any such work would trigger the employer’s obligation to pay that employee a full week’s salary. Where an exempt employee is not furloughed but is working a reduced schedule, employers should be aware that if the reduction in hours causes the employee’s salary to fall below $684 per week, the employee will lose their exemption from overtime premium pay under the FLSA.

Higher education institutions must also consider two other wage and hour requirements. First, any reduction in compensation must only apply prospectively, and employers should give affected employees notice of the impending reduction, in writing. Second, under Massachusetts law, employers must pay furloughed employees all wages owed on the date the furlough is announced, including accrued, unused vacation time. However, the Massachusetts Attorney General’s Office has stated that furloughed employees can defer their accrued, unused vacation time until after the furlough ends. Any such deferral agreement should be obtained in writing. Other New England states may have similar payment obligations when furlough is announced.

Families First Coronavirus Response Act

On March 18, 2020, Congress passed the Families First Coronavirus Response Act, which took effect on April 1. The act’s two provisions relevant to employers pertain to paid sick time (PST) and Emergency Family and Medical Leave (EFML). Private employers with fewer than 500 employees and public employers of any size must provide PST and EFML. Employers will receive dollar-for-dollar federal tax credits for the PST and EFML benefits they pay.

The act requires covered employers to provide 80 hours of PST to an employee unable to work due to:

COVID-19 symptoms and seeking a medical diagnosis;

an order from a government entity or advice from a healthcare provider to self-quarantine or isolate because of COVID-19; or

an obligation to care for an individual experiencing COVID-19 symptoms or a minor child whose school or childcare service is closed due to COVID-19.

The employee’s reason for taking PST will determine their rate of pay during leave. Employees are eligible for PST regardless of how long they have been on payroll.

Covered employers must also provide up to 12 weeks of job-protected EFML to all employees on payroll for at least 30 days who are unable to work because their minor child’s school or childcare service is closed due to COVID-19. The first 10 days of EFML are unpaid, though an employee may use PST during this period. Eligible employees are thereafter entitled to two-thirds of their regular rate for up to 10 weeks, based on the number of hours they would otherwise be scheduled to work. However, the act caps EFML benefits at $200 daily and $10,000 total, per employee.

Notably, the act contains a broad, discretionary exclusion from PST and EFML coverage for healthcare providers, which may affect higher education institutions. “Health care provider” is defined under the act as any employee of various types of medical facilities, including a postsecondary educational “institution offering health instruction,” a “medical school” and “any facility that performs laboratory or medical testing.” This provision, which forthcoming regulations will likely clarify, ostensibly means that an institution that performs medical research or offers classes in healthcare may exclude any employees from PST and EFML benefits.

Emergency expansion of Mass. unemployment insurance

Employees subject to a furlough or reduction in hours may qualify to take advantage of expanded unemployment insurance (UI) benefits. Massachusetts, for example, has waived the usual one-week waiting period for UI benefits, allowing Massachusetts employees affected by COVID-19 (including those permanently laid off) to collect benefits immediately.

The Massachusetts Department of Unemployment Assistance (DUA) has also published emergency regulations to address the onslaught of new UI claims and provide more flexibility for prompt financial assistance to employees affected by COVID-19. All employees who temporarily lose their jobs due to COVID-19 are deemed to be on “standby status” and are eligible for UI benefits, provided they meet certain criteria. A claimant is on “standby” if he or she “is temporarily unemployed because of a lack of work due to COVID-19, with an expected return-to-work date.” The claimant must:

take reasonable measures to maintain contact with the employer; and

be available for all hours of suitable work offered by the claimant’s employer.

The DUA will contact employers to verify its employees are on standby status and ask for an expected return date. An employer can request that an employee go on standby status for up to eight weeks, or longer, if the business is anticipated to close or have operations severely curtailed for longer than eight weeks and the DUA deems the requested time period reasonable.

Other New England states have likewise implemented similar emergency regulations to ease the burden on employees who have been furloughed, subject to a schedule reduction, or otherwise affected by COVID-19. For example, Maine enacted emergency legislation with many of the same provisions as the Massachusetts emergency UI expansion, but went an extra step in extending UI eligibility to employees on a temporary leave of absence due to a quarantine or isolation restriction, a demonstrated risk of exposure or infection or the need to care for a dependent family member because of the virus.

Federal and state lawmakers are considering additional legislation to address the workplace ramifications of the COVID-19 pandemic and will likely continue to do so as new and unanticipated challenges develop. HEIs should actively monitor recent developments and speak with counsel as needed to discuss the impact of additional legislation on their workplaces.

Emily P. Crowley and Robert M. Kaitz are employment and trial attorneys at the Boston law firm of Davis Malm.

M. Gabriela Torres/Claire Buck/Cary Gouldin: At Wheaton College, making the sudden leap from in-person teaching to virtual

Panorama of Wheaton College’s campus, in the small town of Norton, south of Boston

From The New England Journal of Higher Education, a service of The New England Board of Higher Education (nebhe.org)

As our computer screens filled with tiny squares of faces of students and faculty alike, we watched them fidget with their chairs and screens and heard their voices ring in our earphones … Social distancing measures took hold at Wheaton College, in Norton, Mass., forcing the same screen encounters that are now spreading across higher education nationwide.

In the wake of the effort to control the rapid spread of COVID-19, the conversations we have been having with students and faculty are not as different as you might imagine. Both groups described new contexts in which they would be learning: now sharing confined spaces at home with others, unable to have all the answers they needed to understand the future of their work, working through the differences among themselves and the others who now inhabited their unexpectedly virtual classes.

The virtual technologies for connection have included many tools that are now ubiquitous in higher education such as Google Meet and Zoom, a doubling down on course-management system use (in our case, Moodle), shared documents and worksheets, as well as immediate connection tools such as slack and project management tools like Trello.

But perhaps most importantly, this transition has enabled us to see continuity in three key issues that Wheaton’s Center for Collaborative Teaching and Learning (CCTL) has been addressing since it launched a year ago: inclusion and diversity, the educator as learner, and the strategic importance of centers for teaching and learning in the educational mission of colleges and universities.

When students were surveyed about their access to technology, their ability to focus on school projects in their relocated settings and changes in their autonomy to manage their schedule, the inequalities were stark. While some students had stable connections and multiple devices, others were only able to access phones and had no privacy. Similarly, as we got a sense of faculty familiarity with technology and how the changes compelled by social distancing affected child and elder care, it became clear that the move to remote teaching and learning was fraught with inequities.

Differences in access arising from a wide variety of inequalities are always present in higher education, and the transition to our work in the cloud only clarified these. Our work in a close-knit liberal arts college with a social justice bent moved us to pay attention to inclusion. The CCTL was already mandated in its mission to focus on inclusion. To this end, we regularly work with the educators in our college to maximize the access for all learners in classrooms and co-educational spaces such as peer advising and residential life leadership trainings. We work based on the idea that to enable inclusive teaching, we begin by viewing ourselves as learners.

In the past two weeks, we have lost our ability to ignore how much we need to learn about technology and the changing world, but most importantly, to learn about one another. Reframing educators as learners central to our mission was no longer a difficult sell. In the transition to remote teaching, learning to sustain connections with our students is critical as we manage the need for physical distance. A college like ours that has for the past 186 years prided itself as being a community where relationships between faculty and students are fostered and valued is remaking itself anew driven by the need to sustain our connections—albeit, now at a distance. To honor our legacy, our work in teaching and learning is focused on the intentional creation of connection and community. Today, in the midst of physical distancing measures that have been misnamed as “social distance,” and the isolation of lockdowns, this heritage is more important than ever.

A humanized virtual experience

Strategically, our problem became less about learning the tools to make us virtual and more about creating courses where students and faculty alike have the possibility of being successful through a rapidly morphing global crisis. In other words, our problem was how to create a more humanized virtual educational experience that enables our students and us to withstand the unknowns that are to come.

To provide a sustainable and humanized educational experience, the work of the CCTL is grounded on our values: We view our students as full persons, we prioritize our relationships and collaboration with each other, and sustain our commitment to thoughtful and impactful teaching.

In practice, this has meant that, in less than a week, we consulted individually with 25 percent of our faculty with more consultations scheduled in the weeks ahead. We have also facilitated a network of colleagues willing to support their peers with learning new technologies—relationships that we hope will yield as much community as they do technological capacity. Our approach is based on the understanding that proficiency in software tools is not the same as knowing how to use tools to further pedagogical goals. Next week, we begin communities of practice where we can discuss pedagogical strategies as they emerge. Pedagogical practices will require sharing, problem solving and iterative revision as we transition to remote teaching that communities of practice enable. Before COVID-19, Wheaton College did not offer any online courses with regularity. Supporting educators as fully social persons at a time of physical distance, we believe will yield fruit in the student experience.

Though the strategic work of our CTL has moved quickly constructing offerings curated tools, a menu of pedagogical strategies in the span of a week, and one-on-one support, our pre-existing toolkit focused on inclusion, collaboration and connection has been invaluable to our rapid take off.

We have worked to assuage what one college termed “the pressure of feeling that you have to go at it alone.” This work has involved colleagues at all stages of online-readiness. We work with colleagues who have decades of excellence in teaching but who are now just learning to turn on the camera on their computers, as well as with colleagues who are ambitiously trying to recreate classroom discussions through novel use of collaborative mapping tools such as Mural. In both cases, the work we do together revolves around core values: how to teach effectively and compassionately, and keeping the varied student experience that each approach will yield at the center of our concern.

The value of a pedagogy focus offered to colleges and universities by centers for teaching and learning has, in our experience, provided a sense of calm and clarity. Instead of fearing new technologies, our one-to-one approach to a pedagogy-centered transition gave faculty members we heard from the agency they had originally thought they had lost in moving to the cloud. Enabling colleagues to repurpose their expertise as teachers, albeit in a different venue, empowered one colleague to now feel that she can “continue to find the right balance for my students.” Finding balance can sometimes be a challenge, one that she realized she is familiar with in a face-to-face class. In both settings, online and traditional, we balance tools to best support our students’ learning.

M. Gabriela Torres, Claire Buck and Cary Gouldin are co-directors of the Center for Collaborative Teaching and Learning at Wheaton College.

Russ Olwell: Early college programs are way for New England colleges to avoid demographic disaster in years ahead

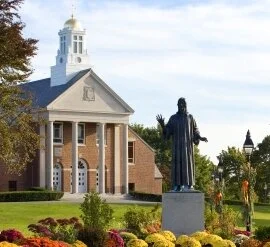

At Merrimack College, a private Augustinian college in North Andover, Mass. It was founded in 1947 by the Order of St. Augustine with an initial goal to educate World War II veterans. The college has grown to encompass a 220-acre campus and almost 40 buildings. North Andover is both a Boston suburb, high end in some places, and also a former mill town. It also hosts the Brooks School, a fancy boarding school.

From The New England Journal of Higher Education, a service of The New England Board of Higher Education (nebhe.org)

This photograph on top from Massachusetts Gov. Charlie Baker’s State of the Commonwealth address last month shows more than just happy college students in their sweatshirts. These students, from Northern Essex Community College and Merrimack College, are part of cohorts of students who have graduated from “early college” programs (with up to a year’s college credit) and successfully matriculated into a two- or four-year college. Recipients of the Lawrence Promise Scholarship at the Haverhill-based (but multi-site) Northern Essex Community College and the Pioneer Scholarship at Merrimack College, these students are on track to graduate on time, and can serve as mentors and role models to young people in their families and in their neighborhoods—proof that college is a real possibility.

Why are these students so important?

The students in the picture, and graduates of similar programs, offer a chance to avoid a demographic crash that faces higher education nationwide (but hits hardest in New England). This is most strikingly laid out in Nathan Grawe’s book Demographics and the Demand for Higher Education, which uses survey data and mathematical modeling to predict the future of higher education. For two-year institutions, regional four-year institutions and all but the top 50 colleges nationwide, the news in Grawe’s book is grim: The decline in childbirths in the wake of the Great Recession of 2008-9 will reverberate into the 2020s and 2030s. This will lead to fewer high school graduates, and fewer students with the family background and finances to propel them into traditional college enrollment.

Grawe considers a full range of possibilities to counteract this curve, such as changes in state higher- education policy, that could increase the proportion of students who might attend colleges, and reduce the racial gaps in groups attending college. In Grawe’s analysis, however, none of these policy tools will close the gap enough to save many higher-education institutions from closing, or from a stark decline in students and revenue.

What can change the curve?

The Commonwealth can try to bend this curve by increasing the number of students who aspire to go to college, and who have the skills to enroll and graduate. One such intervention, which has the potential to scale to the state level, is early college programming, in which high school students are able to take college coursework during the K-12 experience, in order to learn to successfully navigate the college world. Through success in college classes, these students stop thinking of college as a possibility, and instead as something they know they can do.

Early college programs have been a success story in American education, raising enrollments and enhancing student outcomes. Early college programs can help low-income and underrepresented students gain access to higher education and be more successful students once they arrive to college full time, according to research by David R. Troutman, Aimee Hendrix-Soto, Marlena Creusere and Elizabeth Mayer in the University of Texas System.

Early college programs (high school students attending college courses on campus) have shown great impact on academic achievement of students, net return on investment, and graduation rates of participating students.

In successful programs and statewide efforts, students thrive in these programs, are more likely to attend college and are remarkably more successful once they get to campus full time. They are more likely to graduate on time than their peers who attend traditional high schools, and earn a higher GPA.

Recent studies released by American Institutes of Research found the economic return of investment on early college programs to be $15 in benefit for every $1 investment; the U.S. Department of Education’s What Works Clearinghouse recently certified the results of a random-assignment early college study that showed a positive impact in such key metrics as school attendance, number of school suspensions, high school graduation, college enrollment and earning a college credential.

New England has been a growing force in the early college field. Massachusetts now is home to at least 30 designated early college partnerships; Maine has created early college programs for its state four-year colleges, community college and maritime academy; and New Hampshire has launched a STEM-focused early college effort centered on career-technical education and the community college system. While these are far smaller than the efforts in Texas and North Carolina, they are making a positive impact and appealing to a broad range of families.

Scaling and expanding access

Early college programs have not been easy to expand or spread. First, like most successful policy interventions, they are hard to scale without losing the power of the model. The best early college programs are often about 400 students in size, run by dedicated instructors and leadership. Maintaining a size where each student can connect with at least one adult in the building is one of the keys to this work.

This model is hard to scale statewide, which is what would need to happen to have any meaningful impact on the downward curve of college applicants. Early college programs can also suffer from elitism. They can attract smart, ambitious, well-off students and families, leaving behind the populations that can be helped the most by the model. As college costs drive more behavior across the economic spectrum, middle-class and upper middle-class parents will see early college programs as a lifeline, and could seek out opportunities that had previously been designed for lower-income families. In my earlier work in Michigan, I saw programs start to fill up with the children of professors at the college housing the early college, as it was seen to be such a bargain.

However, as early college is embraced by new states and regions, policymakers are paying more attention to making sure that programs can grow, and can retain the characteristics that make the model so effective. As new programs are developed in Massachusetts, there is renewed emphasis on reaching the at-risk students who could be most helped by this intervention. With a push to help all students in a high school leave with some college credit, the impact of early college programs on student enrollment could counteract economic and social barriers to enrollment, moving whole cohorts of students into higher education.

In order for any of the above to have an impact on college enrollment a decade from now, state policy and spending will need to shift, investing in areas such as early college that can help students be successful in college from day one. Most importantly, early college programs and their impact would need broader recognition and support, and would need to be embraced by a wider range of K-12 and higher education leaders than have supported it to date. It might take today’s downward facing enrollment curve to get the attention of policymakers, who up until now have regarded early college with a mix of curiosity and suspicion. To save higher education in Massachusetts, we need more students up in the balcony, graduating from high school with college credit, ready to help their younger peers make the same good decisions.

Russ Olwell is a professor and associate dean in the School of Education and Social Policy at Merrimack College.

— Photo by NAThroughTheLens

An aerial view of the North Andover Old Center showing the North Parish of North Andover Unitarian Universalist Church.

David R. Evans: How is Bulgaria like New England?

Graduating seniors at the American University in Bulgaria

From The New England Journal of Higher Education, a service of The New England Board of Higher Education (nebhe.org)

This question in the headline above probably seems like a lead-in for a funny non-sequitur, but bear with me for a moment.

The American University in Bulgaria (AUBG), in Blagoevgrad, where I currently serve as interim president, was founded in 1991, soon after the fall of communism in Eastern Europe, originally as a branch campus of the University of Maine. Like several other international institutions, AUBG is accredited by the New England Commission of Higher Education, so we’re at least an honorary New England institution. This strategy streamlined initial accreditation and provided us with a base of institutional resources to start from scratch in a country that had no tradition of American-style undergraduate education. We have long since become completely independent, but our roots in New England remain fundamental to our institutional identity.

Our mission was, and remains, to promote democratic values and open inquiry and to provide opportunities for students to experience the freeing—liberating—benefits of the liberal arts. We strive to create engaged, effective citizens, critical thinkers and excellent communicators empowered by their education to take an active role in their professions and communities and always work to make the world better.

In this respect, AUBG embodies a modern version of the ethos that founded so many colleges in New England and spread across the U.S. in the 18th and 19th centuries. While unlike many such institutions, we have no history as a training ground for the clergy, the parallels remain clear: Our founders envisioned a better world and hoped, through establishing this institution, to play a definitive role in bringing that better world into being. In a country where, for nearly a half-century prior to our founding, the absolute last thing the communist government wanted was engaged, empowered democratic citizens who had learned and been encouraged to question and critique everything, our project and mission to bring the outcomes of a good liberal arts education to Bulgaria have been genuinely revolutionary.

AUBG also shares with many small New England colleges some significant challenges. Most importantly, Bulgaria, like many parts of New England, is in a serious demographic crisis. Bulgaria is a small country with a population of just under seven million people. Its population peaked at nearly nine million in about 1985, and has been declining ever since. Moreover, its fertility rate has been below replacement since about 1985 and is now at only 1.6 live births per woman, while the replacement rate is about 2.1. Because AUBG, like most private colleges, is significantly dependent on tuition revenue, and because our primary market is Bulgaria, the steady decline in our national population is something to take very seriously. We are, in short, deep into the worst nightmares that Nathan Grawe has recently articulated in his indispensable book, Demographics and Demand for Higher Education

Unlike institutions in the U.S., we face another specific enrollment challenge. When AUBG was founded, Bulgaria was not a member of the European Union, and the university quickly became an—if not the—institution of choice for Bulgarian young people seeking a top-quality education conducted in English. However, since Bulgaria joined the E.U. in 2007, such young people have a range of options throughout Europe at very favorable prices and have chosen particularly to pursue higher education in the United Kingdom and the Netherlands. Because of generous public support for higher education in the E.U., there are some parallels with the challenges the “free public college” movement poses to private institutions in the U.S., but the complexities of language and culture further complicate these situations.

In Bulgaria and most of our primary markets extending throughout Eastern Europe, we face another issue in that we proudly promote American-style liberal arts undergraduate education (though honestly more in philosophy and educational practice than in our majors, which are highly weighted toward careers in our service region in business, IT, journalism and communications, and politics).

Where in the U.S., comparable institutions face increasing skepticism about the “liberal arts” in general, in our area, the question is more about what a liberal arts education actually is, and how it differs and adds value to the undergraduate experience. The public universities of Bulgaria, of which there are many, tend to follow the European model of institutional specialization, with strong specific emphases rather than a deep investment in broad liberal education. (The technocratic and often applied focus of many of these universities is also surely a relic of communist practices as well.) In that context, as sadly often in the U.S. as well, our stress on general education is often seen as alien and unhelpful, a useless distraction from the actual business at hand. In many cases, our programs require an additional year to accommodate our curriculum’s required breadth, as we follow the traditional American four-year bachelor’s model, and this added time requires a real commitment on the part of our students and their families.

I bring a very particular, painful experience to my work here, because I was the president of the private Southern Vermont College when it closed last spring as a result of declining enrollment and the associated financial stress. I have seen first-hand the challenges that face private colleges in a highly competitive market, with a product not fully understood or appreciated by its clientele, and presenting a value proposition that is not always evident to the people who most need to embrace it. There, our mission was to provide a strong, broad education to a student body comprising mostly first-generation students and students from diverse and high-need backgrounds. Over time, and exacerbated by the broad declines in high school graduates across our region, it became increasingly difficult to manage institutional finances to support affordable access for them and thus to convince them to invest in our institution despite our evident success in supporting students to graduation and successful careers.

At recent professional meetings back in the U.S., in conversations with colleagues, I have been struck by how comparable, if not similar, our challenges are. Like many colleagues, I take strength from the power and importance of AUBG’s mission and from the tremendous success of our alumni, and work constantly to ensure that this mission can endure in the context of unprecedented challenges to a basic model that has, as New Englanders know, developed and supported exceptional leaders for over three centuries.

David R. Evans is interim president of the American University in Bulgaria.

RIP: Seal of Southern Vermont College, in Bennington, 1926-2019

John O. Harney: The latest in the N.E. 'free college' movement

2008–2012 bachelor's degree or higher (5-year estimate) by county (percent)

From The New England Journal of Higher Education, a service of The New England Board of Higher Education (nebhe.org)

The New England Board of Higher Education recently honored Hartford Promise and the Rhode Island Promise Scholarship with 2019 New England Higher Education Excellence Awards. And NEJHE has been paying close attention to innovations—and challenges—facing such “free college” programs.

In June, the Campaign for Free College Tuition (CFCT) lauded NEBHE delegate and Connecticut state Rep. Gregg Haddad for his work helping the land of steady habits become the 13th state to meet CFCT’s criteria for having a robust free college tuition program for its residents.

Under the budget signed by Connecticut Gov. Ned Lamont, eligible students at the state’s 12 community colleges will be able to attend without paying any tuition or fees starting in 2020. Haddad co-chairs the Legislature’s Higher Education and Employment Advancement Committee. He worked on the issue with Sen. Mae Flexer, Senate vice chairman of the Higher Education and Employment Advancement Committee, after the two heard of the enrollment success at Rhode Island Community College under its Rhode Island Promise program. Sen. Will Haskell and Rep. Gary Turco also helped make the legislation happen. Connecticut’s program will provide a “middle dollar” scholarship to all recent high school graduates with at least a 2.0 HS GPA who fill out FAFSA and take at least 12 credit hours each year. “If the student’s Pell Grant fully covers tuition, they will still get a $250 per semester grant to spend on other costs of attending college. The revenue to pay for this new program is expected to come from online lottery sales which have not yet been legally approved. But the budget directs the Governor and the State’s Board of Regents for Higher Education to find alternative sources of revenue should that idea not work out,” the CFCT reports.

Meanwhile, the 2019 Education Next Poll found 60% of Americans endorse the idea of making public four-year colleges free, and 69% want free public two-year colleges. “Democrats are especially supportive of the concept (79% approval for four-year and 85% for two-year). Republicans tend to oppose free tuition for four-year colleges (35% in support and 55% opposed) and are divided over free tuition for two-year colleges (47% in support and 47% opposed).”

A paper from the Institute for Women’s Policy Research explains that while college promise programs offer invaluable opportunities, “eligibility requirements and rules on whether funds can be used to cover non-tuition costs, can exclude students who are older, working, or who have children.”

Writing in The Conversation, William Zumeta, professor emeritus of public policy and governance and of higher education at the University of Washington, notes that “Washington state’s new college affordability initiative differs from the ‘free college’ efforts being undertaken by other states such as Tennessee and Oregon. In other states, such as these, Rhode Island and, soon, Massachusetts, the ‘free college’ initiatives are mostly limited to tuition-free community college for some students. But in Washington state, the Workforce Education Investment Act provides money for students to attend not only a community college, but four-year public and private colleges and universities.”

In a Chronicle of Higher Education piece titled “The Fight for Free College Is Your Fight Too,” Ann Larson, co-founder of the Debt Collective, called on academics to help win back the promise of college as a necessary and vital public good.

There are also critics of free college schemes. They include some families who had to scrimp and save for their children to earn degrees. And Bloomberg recently published this piece by Karl W. Smith, a former assistant professor of economics at the University of North Carolina, under the headline: The Hidden Cost of Free College.

More recently, College of William & Mary economics professor David H. Feldman and Davidson College visiting assistant professor of educational studies Christopher R. Marsicano wrote in USA Today: “While free college has its benefits, its simplicity makes it a regressive policy that will most help the wealthy.”

Feldman and Marsicano propose instead: increasing the maximum federal Pell Grant by 50%; partnering with states by offering a federal block grant for higher education if states appropriate at least a certain dollar amount per full-time student; offering nonprofit colleges and universities that work with significant numbers of lower-income students a small operating subsidy equal to a percentage of the Pell dollars their students receive; and tying any additional grant subsidies and student loan interest rates to accountability measures such as graduation rates and gainful employment for students upon graduation.

Two other key resource for the movement are The Campaign for Free College Tuition and the clearinghouse for College Promise Programs at UPenn.

Expect to hear more about free college as the 2020 elections approach and student indebtedness grows. U.S. Sen. Bernie Sanders’s campaigned for free college in 2016. Most of the other candidates now call for at least two years of free college.

John O. Harney is executive editor of The New England Journal of Higher Education.

Student political engagement in New England and beyond

Student demonstration against Tufts University’s fossil-fuel investments

From The New England Journal of Higher Education (NEJHE), a service of The New England Board of Higher Education (nebhe.org)

Nancy Thomas is director of the Institute for Democracy & Higher Education at Tufts University’s Jonathan M. Tisch College of Civic Life.

In the following Q&A, NEJHE Executive Editor John O. Harney asks Thomas about her insights on higher education, citizen engagement and elections. (A Q&A along the same lines has been conducted with the Edward M. Kennedy Institute for the United States Senate. Watch this space for more on higher education and citizen participation in this critical time for American democracy.)

Harney: What did the 2016 and 2018 elections tell us about the state of youth engagement in American democracy?

Thomas: Only 45% of undergraduate students voted in the 2016 presidential election, compared with about 61% of the general population. People on both sides of the political aisle had strong reactions to the election of Donald Trump as president, making 2016 a wake-up call. That, coupled with some intriguing, diverse candidates and growing issue activism, is a formula for youth engagement. We do not have our numbers for 2018—they will be available in September—but all signs point to a big jump in college student voting. Overall, Americans turned out at record high numbers in 2018.

Harney: How else besides voting do you measure young people’s civic citizenship? Are there other appropriate measures of activism and political involvement?

Thomas: Measuring student civic engagement is tough. In her 2012 review of civic measures in higher education, Ashley Finley at the Association of American Colleges & Universities (AAC&U) concluded that although students participate in a continuum of civic learning practices, we need more evidence of their impact on student development, learning and success.

One problem is a lack of consensus over what counts as engagement. Knowledge about democracy? Intercultural competencies and other skills? Volunteering? Activism off campus? Following an issue on social media? Joining a group with a civic purpose? To measure engagement, many campuses conduct head counts of how many people took certain courses or volunteered or joined a club engaging in issue activism or attended a forum, etc.

Usually, civic engagement and development are measured by self-reported responses to surveys about behavior and attitudes. The CIRP senior survey asks whether students have worked on political campaigns or local problem-solving efforts. And the National Survey of Student Engagement,also a student survey, asks about voting, contributing to the welfare of the local community, and developing cultural understanding and a personal code of ethics.

Another approach is to administer pre- and post-experience questionnaires or require students to write reflective essays about their experiences. Some institutions survey alumni and correlate alumni engagement with learning experiences, if they have kept that record.

To my knowledge there is no objective, quantitative measure of civic engagement, much less political engagement, other than our voting study.

Harney: What are the key issues for college students?

Thomas: College students care about the same issues that most Americans care about—economic stability and jobs, health and access to healthcare, and education quality and access, particularly student debt and college affordability. They also care deeply about civil rights, discrimination and injustice, encompassing a range of concerns: immigration and the treatment of refugees at the border, DACA and, for those not threatened by the possibility of deportation, the treatment of their DACA peers; mass incarceration; criminal justice reform, racial discrimination and profiling; and hate speech and rise of hate groups and crimes. They also care about climate change and gun violence. I should note that, much like any group in the U.S., college students represent nearly all perspectives you can imagine. Right now, these are the issues that appear to be driving them.

Harney: Do they pay as much attention to local and state policy as to national and global?

Thomas: Some do, but it may be specific to the region or state. Or the institution. Around 50% of college students attend local community colleges, and nearly 85% attend college in-state. Local and state politics directly affect them, their families and communities.

It also depends on who is running for office. In Kansas and Iowa in 2018, for example, students turned out to impact the governor’s races. In the 7th Congressional District of Massachusetts, which is home to several universities, young people turned out to elect Ayanna Pressley.

Our office spent a lot of time on the phone during the 2018 midterms, and that was one trend that stood out to us—there was a great deal of feedback from administrators on campuses that students were engaging in local races more than in the past. We heard stories of local interest that often dovetailed with what was happening at the national level: local judicial elections (in the wake of the Brett Kavanaugh hearings), state representative races (amid a number of stories about state legislatures and state power structures), along with students jumping into races themselves, looking to create change.

In 2018, several students ran for local office. A sophomore at Spelman College ran for the local school board and narrowly lost. Rigel Robinson chose to run for local city councilrather than go to grad school right after graduating from UC Berkeley. He won.

That said, students are like all Americans—they care about the presidential election more. In 2014, only 13% of 18- to 24-year-old college and university students voted. That low number reflects national malaise. It also reflects the unique barriers to voting facing first-time voters and student attending institutions away from home. In midterms, students are less motivated to overcome barriers to voting.

Harney: Do they show any particular interest in where candidates stand on “higher education issues” such as academic freedom?

Thomas: They care about student debt and college affordability as significant higher education issues. I don’t think students would frame the issue as being about “academic freedom,” but they do care about speech and expression on campus and efforts by individuals and groups from off campus who come to campus to espouse discriminatory and hateful ideas. Our research on highly politically engaged campuses revealed nuanced attitudes to free expression on campus. Students want it and support it, but not if it crosses a line. The prevailing view is that students want their learning environments to be inclusive and welcoming regardless of race, ethnicity, immigrant status, sex, LGBTQ status and religion. They do not want groups or individuals with hateful ideas to have a platform on campus. Recently, the Knight Foundation published a report that confirmed this but also noted stark differences among different groups. Only four in 10 college women would protect speech over inclusion, compared with seven in 10 men. I have pushed backagainst this zero-sum-game approach of pitting speech against inclusion. The dominant narrative seems to be that speech, even hate speech, is always protected, at least at a public institution. I disagree.

Harney: How do the New England states treat voting rights for the many college students who live out-of-state?

Thomas: For most people, deciding where to vote is easy: They vote in the district in which they live. Students who attend and reside at a college away from home or out of state, however, may also vote near campus. Sounds easy enough, but it isn’t. Some states, for example, require not only evidence of residency but of permanence or intent to remain in the area. But what does that mean? A person has been living in the area for a month? A day? These kinds of standards are difficult to apply to most residents, and as a result, they tend to be applied to college students only.

Going into effect, ironically, right before the Fourth of July 2019, New Hampshire passed a law requiring students to obtain New Hampshire driver’s licenses or register their cars in state in order to register to vote near campus. The law is being challenged by the ACLU, the League of Women Voters and groups of students. Some legislators have also introduced a new bill that would create an exception for students, members of the military, and others living in the state temporarily. I doubt the law will hold up legally, but as of right now, students will need to go to a lot of trouble to vote locally.

The other New England states are not trying to suppress student voting, but there are many laws that could change to make voting easier, such as allowing for same-day voter registration and voting, early voting and longer time periods within which to register.

Harney: Are there any relevant correlations between measures of citizenship and enrollment in specific courses or majors?

Thomas: Yes! Education and library science majors vote at the highest rates; STEM and business majors are among the lowest. Gender might explain these differences to some extent. Women vote at higher rates than men, and fields that are dominated by women are likely to have higher voting rates. But that’s not the entire story. Education students study the historic and essential relationship between education and a strong democracy. The U.S. supports a public education system so that its citizens will be informed and prepared to participate in democracy. Both education and library sciences have a clear public purpose. This doesn’t mean that STEM and business fields do not have a public purpose. They do. But I am not sure the curriculum is designed to teach the public relevance of that field.

Harney: Are college students and faculty as “liberal” as “conservative” commentators make them out to be?

Thomas: Studies of college professors demonstrate that, overall, faculties lean liberal. In some fields like economics, they lean conservative, but overall, the professoriate is progressive. But that does not lead to “liberal indoctrination,” contrary to media reports or unique and inflammatory stories tracked by self-appointed watchdogs. Students do not arrive at college without opinions, nor are they easily manipulated. There is no evidence that students move left politically in college. Indeed, according to a recent study, college exposes students to new viewpoints and teaches them how to think, not what to think.

In our research on highly politically engaged campuses, we found that professors want students to think critically about their own perspectives, not just the perspectives of those with whom they disagree. They assign students projects in which the students must advocate for a position not aligned with their own. They teach using the Socratic method or discussion-based teaching to draw out multiple perspectives on an issue. They get students to work in groups reflecting diverse ideologies and lived experiences. If they do not hear a more conservative perspective expressed, they will introduce it. Do they sometimes take a stand on a political issue, like climate change or civil rights? Yes, but that’s the job. The job is not to be apolitical. Professors can’t cross the line into partisanship by telling students which candidate or party to support. But they can, and should, teach students to think critically about and even take a stand on political problems and solution.

Harney: What are ways to encourage “blue state” students to have an effect on “red-state” politics and vice versa?

Thomas: For better or worse, political polarization is a strong motivator for activism and voting. Young voters believe that they can make a difference and that government can solve public problems. I am confident that energy will continue through 2020.

I worry, however, that other forces like gerrymandering, money in politics, and the way politicians now cater to their “base” rather than all their constituents, will reinforce distrust in our political system. Many Americans believe that their vote doesn’t count or that their elected representatives do not represent them or their views. This leads them to ask, “why bother?”

Unfortunately, they may be right. In June 2019, the U.S. Supreme Court once again rejected efforts to stop partisan gerrymandering, leaving the drawing of districts to state legislators. Many state legislatures (both red and blue) gerrymander their districts to ensure dominance of their party. It is unlikely that politicians will voluntarily give up that power.

What’s the solution? One way to fix this problem is to get people to force their legislators to appoint nonpartisan redistricting commissions. In most states west of the Mississippi, residents can force a change to laws or state constitutions through ballots or referenda. Massachusetts is the only New England state that allows citizen-initiated statutes and amendments to the state constitutions. In 2018, voters in Michigan, Missouri, Colorado, Utah and Ohio passed initiatives to end partisan gerrymandering.

Young people can do the same on issues such as money in politics and extremism in policymaking. Educators should teach about these issues. Remember the old civics courses that taught “how a bill becomes a law?” Let’s resurrect that in college through experiential learning.

Harney: What role does social media play in shaping engagement and votes?

Thomas: Social media plays a significant role in shaping participation by young people. It’s how they get their news and information, find groups and people who care about their issues, and communicate with their peers. At its best, political engagement is a collective, and even social, act. Social media facilitates that.

The downside to social media, however, is misinformation and fake news. Manipulation through social media is a frightening truth. Colleges and universities should teach all students how to distinguish facts and fiction and to identify reliable news sources.

Harney: What do you think of an idea broached in NEJHE about ranking colleges based on the percentage of their students who vote?

Thomas: Some voter competitions compare basic voting rates; others compare election-to-election improvement. I have mixed feelings about using voting rates to compare one institution to another.

On one hand, voter competitions generate enthusiasm. They can be fun, and our research suggests that activities around elections should be spirited and celebratory. Again, engagement, including voting, is a social act. Students vote if their friends vote. Competitions can draw diverse groups to an activity, not unlike sporting events.

On the other hand, voting rates need to be critically examined. We know who the more likely voters are and what predicts voting: gender (women vote at higher rates), age (older people vote at higher rates), race (white, and some years, black Americans vote at higher rates), and affluence (wealthy people vote at higher rates). External factors also affect voting: Is it a battleground state or is student voting suppressed? Competitions will be won by institutions that admit older, affluent white women in states with same-day registration and voting.

The better approach is to calculate expected voting rates for a campus and then compare their actual with the expected, and then recognize campuses that overperform. We’re working on that, but it’s not as easy as it sounds. Student populations and voting conditions change every election. We’ll keep watching this.

We published a set of recommendations for colleges and universities interested in fostering student learning for and participation in democracy, actions that we believe will positively impact voting rates. I’d prefer to see a system that recognizes colleges and universities for how well they educate students about their responsibilities in a participatory democracy. Voting would be a factor, but it would not be the only factor.

Harney: How will New England’s increased political representation of women and people of color affect real policy?

Underrepresentation has been a serious problem in this country for a long time. According to the Reflective Democracy Campaign, white men make up 30% of the U.S. population and 62% of elected officials, while women of color make up 20% of the population and only 4% of elected officials. Practices like gerrymandering, special-interest money, how campaigns get funded, the power of incumbents and so forth allow leaders of political parties to serve as gatekeepers to perpetuate underrepresentation. While we saw historic shifts in 2018, we have a long way to go.

We have a partisan divide in this country that cannot be ignored. Fully 71% of Republican elected officials are white men, compared with 44% of Democrats. Only 3% of Republican leaders are people of color, compared with 28% of Democratic leaders. The historic shifts in 2018 reflect shifts in the Democratic party, not the Republican party.

Today, many politicians do not even pretend to represent people other than “their base” of die-hard supporters. They do not need to. The party in power sets their positions on issues and remains unmoved because they face no consequences for ignoring dissenters or opinion polls. It’s a maddening situation.

So, in answer to your question, increased political representation of women and people of color should affect policy, but the systems need to change to ensure that will happen.

Harney: How can colleges and universities work together to bolster democracy?

We need an industry-wide effort to increase education for the democracy we want, not the one we have. Regardless of their discipline, students need to learn the basics of our Constitutional democracy—how the government is structured, how elections work, how decisions are made and separation of power, and not just rights but responsibilities of people who a fortunate enough to live in a democracy.

I am deeply concerned by a 2019 publication by the Baker Center at Georgetown University that reports that nearly one-third of young Americans feel that living under non-democratic forms of government (e.g., military state or autocratic regime) would be equally acceptable to living in a democracy. That suggests to me a need for an educational response at the K-12 and higher education level.

But it also points to the need for systemic reform. Colleges and universities not only need to teach what a strong democracy looks like and why students have a responsibility to work for democracy’s health and future, but also need to enable student activism on electoral reform. They need to teach students how to run for office or how to effectuate policy change through laws and ballot initiatives. Students need to get involved in changing systems that underrepresent and disempower most groups of Americans. As I mentioned earlier, young people care deeply about equal opportunity and equity, along with other issue advocacy. The academy’s opportunity is now. It’s time to seize it.

Jeffrey Roy/Edward Lambert Jr.: Listen to Lowell students on expanding vocational opportunities

From The New England Journal of Higher Education, a service of The New England Board of Higher Education (nebhe.org)

A shared challenge for our higher education institutions and employers is the large number of students graduating high school unprepared for success in college and the workforce. It leads to lower-than-acceptable college completion rates, particularly for our most disadvantaged youth, and a broken workforce pipeline that threatens economic growth and opportunity.

The lack of skilled workers to fill open positions is a growing concern for our economy. The talent search firm Korn Ferry has estimated that the U.S. could face a deficit of 6.5 million highly skilled workers by 2030, and the skills gap could cost the country $1.75 trillion in revenue by that same year. More important, our failure to better connect k-12 education to college and workforce success translates into lost opportunities for students. Put simply, we need to do more to help young people seize the many excellent opportunities our economy creates.

A proposal we have introduced and are championing in Massachusetts aims to do just that. House Bill 567 would expand opportunities for high school students to earn industry-recognized credentials (IRCs) that data confirm are of high employment value. The proposal will fuel a diverse, highly skilled workforce pipeline that is the engine of growth and prosperity and provides students with opportunities for upward mobility.

Many students in our vocational technical schools are already earning IRCs in information technology, welding, construction, healthcare and other fields. We can and should make these available to students in our traditional high schools as well. IRCs certify the student’s qualifications and competencies and are often “stackable,” meaning they can be accumulated over time to build the student’s qualifications to pursue a career pathway or another postsecondary credential. Some IRCs also earn the student college credit.

For students going directly into the workforce from high school and for those who enter but never complete college, credentials can be the difference between low-wage positions and better paying jobs that offer opportunities for growth. Earning credentials in high school can also lead to stronger preparation for higher education. Students who earn them are exposed to career pathways before entering college and deciding on a major. In Florida, students earning credentials in high school were more likely to take Advanced Placement or dual-enrollment courses and to go to college.

We heard from students at Greater Lowell Technical High School in Massachusetts who have earned multiple web development, programming and IT credentials that having those credentials will help them secure the higher paying jobs they need to help them afford their college education and in the fields they plan to ultimately pursue.

Our legislative proposal would require the state Executive Office of Labor and Workforce Development to provide the Department of Elementary and Secondary Education with an annual list of high-need occupations that require an industry-recognized credential, ranked by employment value. The top 20% of the list will be credentials that lead to occupations with annual wages at 70% of average annual wages in the Commonwealth. The idea is to ensure we’re sending the right signals to schools and students about where the opportunities lie. The district would get a financial award for each student who earns a credential that has high employment value, is recognized by higher education institutions and addresses regional workforce demands identified by the local MassHire Workforce Board. To ensure that all districts have equal opportunity to participate, the bill includes start-up funding for implementation to encourage less well-resourced districts to get the programs up and running. The funds can support teacher training or cover assessment costs or equipment needs.

This proposal dovetails and complements several state and regional initiatives already underway, including the New England Board of Higher Education’s High Value Credentials for New England initiative launched last summer that is identifying high-value credentials in key growth industries and making that information more easily accessible to the public. The ultimate goal is to enable students to make informed decisions about their course of study and future employment opportunities.

Several other states have adopted similar incentive strategies or integrate credentials into the school curriculum and career preparation activities like work-based learning and internships. In Ohio, students can earn industry-recognized credentials in one of 13 career fields with a choice of more than 250 in-demand credentials. Students in any district can sign up for an industry-recognized credential course. Florida, Wisconsin and Louisiana provide a financial incentive such as the one we propose. Students enrolled in the program in Florida demonstrated higher GPAs, graduation rates and postsecondary enrollment rates.

Massachusetts can provide these important opportunities to students in our traditional and comprehensive high schools by providing the right incentives to our schools. It is an important step in addressing our urgent need for a highly skilled workforce and ensuring our education system is creating pathways to economic opportunity and success.

Jeffrey Roy is a member of the Massachusetts House of Representatives and chairs the Joint Committee on Higher Education and the Legislature’s Manufacturing Caucus. Edward Lambert Jr. is executive director of the Massachusetts Business Alliance for Education.

Neeta Fogg/Paul Harrington/Ishwar Khatiwada: Measuring the GEAR UP program for R.I. students

From The New England Journal of Higher Education, a service of The New England Board of Higher Education (nebhe.org)

‘The federally financed GEAR UP (Gaining Early Awareness and Readiness for Undergraduate Program) was organized two decades ago with the purpose of increasing high school completion and college enrollment among low-income students. The College Crusade of Rhode Island’s GEAR UP program was designed as a long-term effort to buttress student success by providing various kinds of educational and social service supports beginning in the sixth grade and continuing through high school completion.

Back in 2015, the authors completed the first study in the nation that measured the net impact study of a GEAR UP program. That study track a cohort of entering sixth-graders who participated in the College Crusade GEAR UP program relative to a comparison group selected with the rigorous Propensity Score Matching (PSM) method that creates a comparison group with traits equivalent to the participant group at the time of sixth grade entry into the program. This baseline equivalency at the time of program entry means that differences in outcomes that occur between the participant and matched comparison groups are attributable to participation in the GEAR UP program.

That longitudinal impact study found substantial and statistically significant gains for a single cohort of GEAR UP program participants relative to the comparison group on the likelihood of completing high school on time and immediately enrolling in college in the fall following high school completion, providing evidence that the College Crusade of Rhode Island was able to substantially improve these two important educational outcomes of GEAR UP participants.

While high school completion and college enrollment have remained high priorities for the nation’s education system, in recent years, much greater attention has been focused on college retention and completion. This raises the question about the lasting effects of participation in the College Crusade’s GEAR UP program. Do the gains that the program provided in the sixth through 12th grades persist for participants once enrolled in college? At the time that these cohorts of students were participating in the College Crusade GEAR UP program, participants who were enrolled in college did not receive any systematic support from the College Crusade. This created the opportunity for us to examine whether the sizable impacts of GEAR UP participation in middle school and high school persist beyond high school completion and immediate college enrollment or do they fade out after entry into college.

Enough time has now elapsed for three cohorts of College Crusade GEAR UP participants to have completed their first year of college, providing an opportunity to measure the impact of participation in the College Crusade GEAR UP program beyond initial college enrollment.

The effects of participation in the College Crusade GEAR UP program are cumulative; that is, we found that the program was able to increase the likelihood of on-time grade attainment for participants relative to the matched comparison group for each year after initial enrollment in the sixth grade. The cumulative effects of these positive outcomes in each successive year for participants relative to comparison group students become quite sizable as students progress from middle school to college.

The chart below illustrates the divergent educational pathways of College Crusade participants and their matched comparison group counterparts. Beginning in the eighth grade, a gap emerges between participants and comparison group students in the likelihood of staying on track; and the size of this gap continues to grow in each successive grade/year. By the time of high school graduation, the gap had grown to 9.3 percentage points in favor of GEAR UP participants; 77% of the three cohorts of participating students had graduated from high school on time compared with just 67% of their counterparts in the matched comparison group. During the fall term following their expected on-time high school graduation, 56% of the three sixth grade participant cohorts had enrolled in college, compared with 42% of the three 6th grade comparison group cohorts.

Eight years after the beginning of sixth grade when these three cohorts of participants had enrolled in the College Crusade GEAR UP program, 40% had returned to college after the freshman year, relative to 30% among their matched comparison group counterparts.

This means that the cumulative impact of the College Crusade’s GEAR UP program was to increase the relative likelihood of a low-income sixth grader in Rhode Island to progress through middle and high school and complete a year of college by 35%.

The Pathway from Sixth Grade to One Year of College Retention, Combined Sixth Grade Cohorts, 2007-08, 2008-09 and 2009-10

These findings reveal that the College Crusade’s GEAR UP program had a cumulative effect that reached beyond its formal goals of high school completion and college enrollment. The cumulative gains for participants relative to the comparison group increased each year though high school graduation and college entry. Beyond that, despite no formal GEAR UP services for participants once enrolled in college, the gains to their earlier participation in the program continued. No evidence of a fade out of the substantial positive effects of GEAR UP participation is found one year after participants had exited the program.

The first year results are promising, but the kinds of obstacles to degree attainment that low-income college students confront are associated with complex academic, social and financial issues that are somewhat different from the barriers that these students face in completing high school and initially enrolling in college Will these cumulative one-year college retention gains persist through college completion with no fade out effects? Stay tuned.

Neeta Fogg is research professor at the Center for Labor Markets and Policy at Drexel University. Paul Harrington is director of the center. Ishwar Khatiwada is an economist there.

These findings reveal that the College Crusade’s GEAR UP program had a cumulative effect that reached beyond its formal goals of high school completion and college enrollment. The cumulative gains for participants relative to the comparison group increased each year though high school graduation and college entry. Beyond that, despite no formal GEAR UP services for participants once enrolled in college, the gains to their earlier participation in the program continued. No evidence of a fade out of the substantial positive effects of GEAR UP participation is found one year after participants had exited the program.

The first year results are promising, but the kinds of obstacles to degree attainment that low-income college students confront are associated with complex academic, social and financial issues that are somewhat different from the barriers that these students face in completing high school and initially enrolling in college Will these cumulative one-year college retention gains persist through college completion with no fade out effects? Stay tuned.

Neeta Fogg is research professor at the Center for Labor Markets and Policy at Drexel University. Paul Harrington is director of the center. Ishwar Khatiwada is an economist there.

Stephanie M. McGrath: N.E. colleges -- falling enrollments, higher tuitions

Presque Isle, Maine, site of the most remote state university campus in New England.

From the New England Journal of Higher Education, a service of the New England Board of Higher Education (nebhe.org)

Tuition and fees across New England have risen by 16 percent ($734) at community colleges and 10 percent ($1,001) at four-year public institutions since 2012-13, according to NEBHE’s 2017-18 Tuition and Fees Report.

The report, published annually by NEBHE’s Policy & Research team, takes an in-depth look at the tuition and required fees published by public two- and four-year postsecondary institutions across New England. It explores emerging trends by providing a historical analysis of tuition and fees in the region to shed light on college prices, as well as legislative and institutional initiatives that seek to address affordability challenges.

In New England and across the U.S., it has never been more critical to hold a postsecondary credential to be able to fully participate in the workforce and earn a sustainable wage. Roughly 90 percent of the jobs available in four of the nation’s five fastest growing occupational clusters require some form of education beyond high school, according to research at the Georgetown University Center for Education and the Workforce. The same study estimates that 63 percent of all jobs available nationwide in 2018 require a postsecondary degree. As a result, employers will need approximately 22 million new employees with a postsecondary degree.

However, in recent years the cost of a college degree has risen precipitously resulting in rising tuition and fee charges–often prohibitively expensive for far too many Americans to attend college. As postsecondary education becomes increasingly important for the vitality of New England’s economy and its workforce, the growing cost of higher education has garnered substantial critical attention from the public and from policymakers. New England’s public colleges continue to be the most affordable and financially accessible option for most individuals in the region. Their primary mission is to serve their state’s residents. Tuition and fees at public colleges are of particular interest to both students and state policymakers.

Among other key findings in the NEBHE report:

From 2015 to 2016, enrollment at New England’s public colleges and universities declined by 1.8 percent, or 8,036 fewer undergraduates — a trend that is expected to continue in years to come due to a projected 14 percent decline in the number of new high school graduates in New England by 2032.

On average, in 2017-18, the federal Pell Grant covers approximately 49 percent of tuition and fees at four-year institutions for students in the lowest income quintile ($0-$30,000 annual household income).

Since 2012-13, increases in tuition and fees at New England’s two-year colleges (16 percent) and four-year institutions (10 percent) have outpaced increases in the maximum Pell Grant (6.25 percent), leaving a widening gap for low- and moderate-income families to offset with additional aid and/or family resources.

These trends are putting pressure on institutions and systems to find creative solutions to ensure that college is affordable for students, maintain enrollment and meet the needs of regional employers, who increasingly demand workers with postsecondary credentials.

In Massachusetts, a state known for its high in-state tuition prices, Gov. Charlie Baker announced in his 2018 State of the Commonwealth Address that the Bay State will increase college scholarship funding by $7 million so that the state’s lowest-income community college students with an unmet financial need can have the remaining balance of their tuition and fees fully covered.

Connecticut passed legislation during its 2018 session to allow undocumented students who attend one of its public colleges and universities the opportunity to qualify for the state’s financial aid. Previously, these students were not granted access to the financial aid system by state law but had been offered in-state tuition.

The University of Maine System launched a promise initiative in which, beginning in fall 2018, first-year Maine students who qualify for a federal Pell Grant are able to attend the University of Maine campuses at Presque Isle, Fort Kent, Augusta, and Machias free of having to pay any out-of-pocket tuition and fees. Beneficiaries of the initiative must commit to take a minimum of 30 credit hours each academic year and maintain at least a 2.0 GPA. As of October 2018, the initiative has resulted in a 2.5 percent increase in enrollment at these institutions over the previous year.

Click below to view individual state data used in the report:

Stephanie M. McGrath is NEBHE’s policy & research analyst.

Readers may comment on this and other New England Diary articles by emailing to:

Rwhitcomb4@cox.net

Jennifer Ware: When bad stuff comes from technology

Via The New England Board of Higher Education (nebhe.org)

It’s an unpleasant reality, but also an inevitable one: Technology will cause harm.

And when it does, whom should we hold responsible? The person operating it at the time? The person who wrote the program or assembled the machine? The manager, board or CEO that decided to manufacture the machine? The marketer who presented the technology as safe and reliable? The politician who helped pass legislation making the technology available to consumers?