N.E. Council COVID-19 update: Beth Israel's new testing swabs; Samuel Adams aid program and more

— Photo by Raimond Spekking

BOST0N

From The New England Council (newenglandcouncil.com)

As our region and our nation continue to grapple with the Coronavirus disease (COVID-19) pandemic, The New England Council is using our blog as a platform to highlight some of the incredible work our members have undertaken to respond to the outbreak. Each day, we’ll post a round-up of updates on some of the initiatives underway among council members throughout the region. We are also sharing these updates via our social media, and encourage our members to share with us any information on their efforts so that we can be sure to include them in these daily round-ups.

You can find all the council’s information and resources related to the crisis in the special COVID-19 section of our Web site. This includes our COVID-19 Virtual Events Calendar, which provides information on upcoming COVID-19 Congressional town halls and webinars presented by NEC members, as well as our newly-released Federal Agency COVID-19 Guidance for Businesses page.

Here is the April 6 roundup:

Medical Response

Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center Develops Prototype Testing Swabs – Confronting a shortage of testing swabs, Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center (BIDMC) is leading efforts to mass-produce swabs. After only 15 days of research with both private and public partners, BIDMC expects to produce 10,000 swabs each day beginning next week week, eventually ramping up to 1 million daily—likely enough to supply all of America and part of Europe. Read more in The Boston Business Journal.

MIT Researchers Create Equipment Decontamination Resources– To provide advice on best practices for decontaminating and reusing protective equipment used by healthcare providers, researchers at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) entered a consortium to create an online resource page. The site aims to help providers with limited time and resources make informed decisions on how to best use existing supplies. More from MIT News

Economic/Business Continuity Response

Boston University Provides Online Learning Resources for Deaf Children – Boston University (BU) has created a new resource—the Deaf Education Library—for deaf children to access courses, curriculum, and books in American Sign Language while they learn at home. In providing this new tool, BU noted that deaf children can find themselves in “double seclusion” as they navigate both the transition to remote learning and being sequestered with people who may struggles to communicate with them. BU Today has more.

Verizon Increases Access to Internet Resources, Employee Pay – To facilitate as smooth a transition as possible to remote work and learning, Verizon is offering access to learning tools and news channels at no additional cost. The network provider has also expanded its Pay It Forward Live gaming campaign to support small businesses affected by the outbreak, and has committed to increasing the pay for its essential employees. Read more.

Lowe’s Takes Steps to Protect Employees – To best comply with social distancing protocols, Lowe’s is working to ensure that its essential employees are protected during the pandemic. Lowe’s announced measures to restrict the number of customers in locations and has expanded remote purchasing offerings. The more stringent guidance come after Lowe’s $170 million commitment to relief efforts. Read more in The Charlotte Business Journal

Community Response

City of Boston Announces $2 Million Small Business Relief Fund – Boston Mayor Martin Walsh announced a relief fund to support small businesses directly affected by closures due to the COVID-19 pandemic. The fund—with contributions from city, private, and federal sources—will target those businesses that do not qualify for federal relief or unemployment benefits. The Boston Business Journal has more.

Northeastern University to Provide Employment and Educational Opportunities for Third-Party Employees – Northeastern University will provide educational assistance and temporary employment opportunities for campus workers who employed by third-party vendors, such as those working in dining and parking services—. Utilizing its existing network of employers usually used for its co-op program, the university will provide language, educational, and career support to address the immediate needs of these workers. Read more from News@Northeastern

Samuel Adams Offers $1,000 Payments to Out-of-Work Food Industry Employees – After establishing its Restaurant Strong Fund to raise money for workers in food service affected by revenue losses, Samuel Adams (part of Boston Beer Company) has expanded the fund’s operations to 19 additional states and is now offering a $1,000 grant to workers who have suffered financial hardship due to the pandemic. CBS Boston has more.

Stay tuned for more updates each day, and follow us on Twitter for more frequent updates on how Council members are contributing to the response to this global health crisis.

John O. Harney: News and random thoughts from the region

“If Wishes Were Horses (For Dad)”, by Timothy Harney, a professor at the Montserrat College of Art, in Beverly, Mass. He’s the brother of John O. Harney.

From The New England Journal of Higher Education, a service of The New England Board of Higher Education (nebhe.org)

FICE-y conditions. MIT recently alerted its staff that federal immigration officials would be checking the status of foreign postdoctoral students, researchers and visiting scholars in the sciences, and urged them to cooperate. … Meanwhile, an Iranian student, returning to study at Northeastern University, was detained at Boston’s Logan International Airport then deported, despite having a valid student visa and court order permitting him to stay in the U.S. The stories reminded me of Politico’s report on “5 ways universities can support students in a post-DACA world” by Jose Magaña-Salgado, of the Presidents’ Alliance on Higher Education and Immigration. And of own NEJHE piece by Harvard attorney Jason Corral, whose job is advising undocumented students in the age of the Trump administration.

Caste away. Brandeis University announced it will include “castes” in its non-discrimination policy. Discrimination based on this system of inherited social class will now be expressly prohibited along with more familiar measures such as race, color, religion, gender identity and expression, national or ethnic origin, sex, sexual orientation, pregnancy, age, genetic information, disability, military or veteran status.

Institution news. Massachusetts approved new regulations on how to screen colleges and universities for financial risks and potential closures. … The University of Maine System Board of Trustees adopted a recommendation from Chancellor Dannel Malloy to transition the separate institutional accreditations of Maine’s public universities into a single “unified institutional accreditation” for the 30,000-student University of Maine System through the New England Commission on Higher Education (NECHE). One institution the UMaine System is likely to collaborate with according to Malloy’s office: Northeastern University’s planned Roux Institute for advanced graduate study and research to open in Portland, Maine. … In Connecticut, meanwhile, Goodwin College became Goodwin University. Such rebranding has been something of a trend in recent years. … In other institution news, monks at Saint Anselm College challenged the New Hampshire Catholic college’s board of trustees over a move the monks say could lead to increased secularization. The college’s charter dictated that the monks have the power to amend laws governing the school. Saint Anselm College President Joseph Favazza said in a letter that the board was not trying to change the mission of the college, but rather aiming to meet the standards set by NECHE, the accrediting body.

Cold War chills. Primary Research Group Inc. has published its 2020 edition of Export Controls Compliance Practices Benchmarks for Higher Education with this grim reminder: “Increasingly, U.S. universities and their corporate and government research partners are under pressure to demonstrate compliance with U.S. export control and other technology transfer restriction and control policies. The deterioration of U.S.-relations with China and Russia threatens the return of export control philosophies common during the Cold War. Major universities in the U.K., Australia and Canada, among other countries, are experiencing similar changes.”

Media is not the enemy, but … The free Metro Boston newspaper ended operation after 19 years, following the sale of the New York and Philadelphia Metro papers. One explanation offered by a columnist at The Boston Globe, which is a part-owner of the Boston Metro: more commuters using their phones to catch up on news.

Latest from LearnLaunch. Watch NEJHE for reports from the 2020 Learn Launch Across Boundaries Conference, including an exclusive Q&A with the new LearnLaunch president, former Massachusetts Gov. Jane Swift.

John O. Harney is executive editor of The New England Journal of Higher Education.

George McCully: The importance of 'Reshaping MIT'

On the Massachusetts Institute of Technology campus, in Cambridge, Mass.

Via The New England Journal of Higher Education, a service of The New England Board of Higher Education (nebhe.org)

A review of The New Education: How to Revolutionize the University to Prepare Students for a World in Flux, by Cathy N. Davidson (New York, Basic Books, 2017); a summary of the recent announcements of a major restructuring of MIT, and a synthesis of other relevant developments.

It is increasingly obvious that we are living in one of the greatest ages of paradigm-shifts in Western history, comparable to the Renaissance and the fall of Rome. As with Gutenberg in the Renaissance, today’s is driven by revolution in information technology—the rise of computers, the internet, and now artificial intelligence (AI). The pace has dramatically accelerated—previously such momentous shifts took centuries to be resolved; ours is taking decades. Higher education, which is certainly information-intensive, is being so rapidly transformed that, whether we know it or not, every institution is in crisis. Leaders need urgently to mobilize their faculties, staffs and boards to face facts and respond. Problem-solving innovations are everywhere; strategic overview is needed.

In 1869, Charles W. Eliot lost a competition for the endowed chair in chemistry at Harvard ( surprisingly, considering that he was a Boston Brahmin and a deeply connected alumnus); he then joined the faculty at MIT and, funded by a modest inheritance from his grandfather, toured European and particularly German universities and technical institutes, returning to write an article in The Atlantic Monthly titled “The New Education,” in which he argued that higher education at the time needed urgently to be modernized, to prepare future managers of industrialization and urbanization. He was shortly thereafter chosen to be president of Harvard at age 35, where for the next four decades his reforms played a top-down leading role in setting the model for twentieth-century American scholarship and higher education.

Now comes Cathy Davidson—a prominent strategist in higher education, longtime professor at Duke University and its vice provost for interdisciplinary studies, currently director of The Futures Initiative at the City University of New York (CUNY)—who has explicitly invoked Eliot’s title and spirit to declare that today, we are at a similar inflection point in the history of higher education, and for the same reason: that it no longer adequately prepares students for the world in which they will live. In response, she has provided a compendium of exemplary institutional innovations, useful as a guide for reformers elsewhere.

The governing paradigm of scholarship and higher education has been the modern multiversity, in which knowledge and skills of separate and exclusively specialized conventional academic disciplines were passed on in lecture and reading courses to receptive students, to equip them for their future professional careers. This system she says, and many agree, is obsolete and actually counter-productive. As a result, the future of higher education is this time being led from the ground up, all across the country, in myriad kinds and levels of institutions, especially including community colleges where fully half of the nation’s undergraduates now matriculate.

Disruptively innovative experiments in curricula, teaching and participatory learning are burgeoning, led by “smart” faculty who have given up on the inherited models and are pioneering new pathways that are public problem-oriented and “student-centered” rather than discipline centered. Their common denominator, she says, is teaching students how to teach themselves— “learning how to learn” for real-world problem-solving in volatile “gig” job markets, using rapidly advancing new information technology in practical situations and terms—in short, the opposite of the traditional paradigm of conventional multiversity academicism.

She does not mince words. She says today’s students are being swindled, not getting what they’re in any case paying far too much for, and that there needs now to be “a revolution in every classroom, curriculum, and assessment system … To revolutionize the university, we don’t just need a model. We need a movement [that] seeks to redesign the university beyond the inherited disciplines, departments, and silos, by redefining the traditional boundaries of knowledge and providing an array of intellectual forums, experiences, programs, and projects that push students to use a variety of methods to discover comprehensive and original answers.”

Building a movement

Her book addresses the need to build the desired “movement” by calling attention to the fact that it is already underway on “almost every college and university campus right now” where “smart educators—sometimes a handful of visionaries, sometimes a substantial cohort—are working on new models for higher education.”

The structure and style of her book is, accordingly, anecdotal—necessarily so, given the novelty of the movement, its innumerable and widespread expressions, and therefore the paucity of systemic historical data. But she is an excellent storyteller, vividly conveying the personalities and characters of the diverse people and institutions involved in new experiments. She presents the “new education” as “student-centered” also faute de mieux—because today’s excessively high-cost and -loan-financed conventional classrooms are not helping today’s students to obtain reliable credentials for predictable future careers. The world is changing too rapidly, driven by technological revolutions in every field.

Her argument is in general carefully and intelligently laid out—this book certainly deserves wide readership by everyone interested in the future of higher education at their own and other institutions. There are chapters on students in crisis, on excessive “technophobia” and “technophilia,” the failures of higher education business models, the reductionism of quantification and grading, the unfairness of elitism and the deleterious effects of all these on American society.

An essential aspect which could only be alluded to, however, is how they relate to the substantive issues of scholarship and research. The multiversity strategy and structure of exclusive specialization by conventional disciplines—the content of higher education that was long the focus of the academy—has been increasingly criticized as inadequate in addressing complex real-world problems such as climate change, environmental degradation, disparities of wealth, overpopulation, energy needs, technological revolutions, etc., which are not organized in the separate parts of the disciplines. This discord has been exacerbated by technological revolutions—rapidly unfolding, accelerating and increasingly powerful, especially in information technology, big data and data science. Although Davidson’s focus is on “student-centered” innovations, a number of her examples involve extra-disciplinary research by the faculty as well.

The College of Computing at MIT

The content of scholarship and pedagogy is the focus of a truly revolutionary new transformation in higher education—the “College of Computing” introduced last October at MIT and certain to be widely influential on the future of technology and of career-training in STEM and all other related fields. While there is no book or even widely published report on it yet, we may summarize its rationale from MIT’s official public statements, to help place Davidson’s book in its most up-to-date and concrete context.

MIT has been structured in five Schools: Science, Engineering, Architecture and Planning, Management, and Humanities/Arts/Social Sciences. The College of Computing is a self-financed addition to that mix, conceived as a “connective tissue for the whole Institute,”in which all faculty and students in all “Schools” will participate. Its “central idea” is that this new “shared structure can help deliver the power of computing, data science, and especially AI, into all disciplines at MIT; lead to the development of new disciplines; and provide every discipline with an active channel to help shape the work of computing itself.”

This “new approach [is] necessary because of the way computing, data, and AI are reshaping the world.” Here computing will be “baked into the curriculum, rather than stapled on.” Students and researchers will be “bi-lingual” and thus of immense value to their employers—taught to use AI in their disciplines from first principles, instead of dividing their time between computer science and other departments, predicated by the fact that “Computing is … everywhere, and it needs to be understood and mastered by almost everyone.” “AI in particular is reshaping geopolitics, our economy, our daily lives and the very definition of work. It is rapidly enabling new research in every discipline and new solutions to daunting problems. At the same time, it is creating ethical strains and human consequences our society is not yet equipped to control or withstand … In response, we are reshaping MIT.”

“Reshaping MIT” is of immense strategic importance to the future of higher education because MIT is in a unique position to assume a global leadership role. AI itself originated there in the 1950s, with the work of Marvin Minsky and others. The Turing Award, computing’s highest honor, so far awarded to 67 scholars worldwide, is held by 10 current MIT faculty. The largest laboratory at MIT is the Computer Science and Artificial Intelligence Lab, established in 2003. Electrical Engineering and Computer Science (EECS) is by far MIT’s largest academic department. U.S. News and World Report cites MIT as No. 1 in six graduate engineering specialties, and 17 disciplines and specialties outside of engineering, from biological sciences to economics.

From that exalted platform, this innovation begins with clear and powerful advantages: impetus from technology both within and outside MIT, and the inexorable rise of AI; MIT itself, as a highly extraordinary and well-resourced stage; an initial investment of $650 million already in-hand, including the launching gift of $350 million from a single donor, anticipating a $1 billion total investment; increasing pressure from students, 40% of whom at MIT are already majors or joint majors in Computer Science; and bold, thoughtful, leadership consensus from both administration and faculty.

Startup funding will enable immediate commencing of student enrollments in 2019; begin construction of an already-sited major new building centrally located on the MIT campus; endow 50 new faculty appointments within five years—half located within the College and half jointly with other departments across MIT, for which jockeying has begun—a 5% growth in total faculty, nearly doubling MIT’s academic capability in computing and AI.

The College will develop new curricula connecting computer science and AI with other disciplines; host forums to engage national leaders from business, government, academia and journalism, to examine the anticipated outcomes of advances in AI and machine learning, and to shape policies around the ethics of AI; encourage scientists, engineers, and social scientists to collaborate on analyses of emerging technology and on research that will serve industry, policymakers, and the broader research community; and offer a seed-grant program for faculty, and a fellowship program to attract distinguished leaders from universities, government, industry, and journalism.

The College’s influence will be reciprocal with all other entities, encouraging the future of computing and AI to be shaped by insights from other disciplines, as well as vice-versa. It will “foster breakthroughs in computing, particularly artificial intelligence—actively informed by the wisdom of other disciplines.” It will deliver the power of AI tools to researchers in every field and advance pioneering work on AI’s ethical use and societal impact.

Its educational aim is to generate “new integrated curricula and degree programs in nearly every field, to equip students to be ‘bi-lingual’—as fluent in computing and AI as they are in their own disciplines and ready to use these digital tools wisely and humanely to help make a better world.” MIT President Rafael Reif says, “Society has never needed the liberal arts—the path to wise, responsible citizenship—more than it does now. It is time to educate a new generation of technologists in the public interest.”

This momentous innovation is intended to strengthen MIT’s position as a key international player in “the responsible and ethical evolution of technologies that are poised to fundamentally transform society. Amid a rapidly evolving geopolitical environment that is constantly being reshaped by technology, the College will have significant impact on our nation’s competitiveness and security.”

The lead donor, Stephen A. Schwarzman, founder of Blackstone, the investment firm, hopes that the College of Computing “will constitute both a global center for computing research and education, and an intellectual foundry for powerful new AI tools. … With the ability to bring together the best minds in AI research, development, and ethics, higher education is uniquely situated to be the incubator for solving these challenges in ways the private and public sectors cannot. Our hope is that this ambitious initiative serves as a clarion call to our government that massive financial investment in AI is necessary to ensure that America has a leading voice in shaping the future of these powerful and transformative technologies.”

Two complementary approaches

We have, then, two complementary approaches to the future of higher education: Davidson’s focus is mainly procedural, broadly based and especially concerned with higher education’s role in creating upward mobility for all students, for the health of American society; MIT’s focus is mainly substantive, initially centered on this single though world-leading institution, and aimed at clarifying, strengthening and refining the force and impacts of today’s revolutionary research and technology. Each of these approaches needs the other—MIT’s will influence the content of future research and teaching across the whole of Davidson’s movement; it would also help if Davidson’s concern for the upward social mobility of all students found special and explicit “multi-lingual” expression in guaranteeing the broadest possible student input to our national future.

Both are happening amid a cascade of powerful and mutually conducive developments. The New York Times recently reported that student demands for computer science are exploding far faster than faculties can adequately supply now or in the foreseeable future. The number of undergraduate majors more than doubled from 2013 to 2017, while tenure-track faculty ranks rose 17%, and graduate student enrollments rose 13%. Part of the problem is that corporate demand for computer scientists is also exploding, so businesses are poaching faculty and new PhD’s away from academia at much higher salaries, forcing universities to make diluting dual appointments. While the multiversity featured cross-fertilization between corporate and academic activities, this current further blending of the two realms may intensify to combine them at both faculty and student levels, further undermining strictly academic disciplines and even producing new ways of organizing research and teaching.

Maldistributions in societal structures further exacerbate those in higher education. Extreme and worsening imbalances of wealth and income are well-known, but less familiar are their damaging effects on public education and training. Re-tooling skills of the lowest-income workers for higher-paying jobs is already a crisis, but add to that, the conservatively estimated 1.37 million U.S. workers who will lose their jobs to automation in the next decade alone, increasing rapidly thereafter, and “upskilling” them would cost $34 billion, 86% of which would have to be covered by government, which has been steadily reducing its support of higher education for several decades.

Globally, China presents another challenge—owing to the massive investment its government is making in AI technological development and the huge numbers of scientists being trained. A recent survey asked Chinese and American executives whether they thought AI would have a larger impact than the internet; 84% of the Chinese said yes, while 38% of Americans agreed. Currently 25% of Chinese business leaders say AI is used on a wide scale at their firms, whereas only 5% of U.S. executives said the same. In June, the Pentagon announced that it was establishing a Joint Artificial Intelligence Center that will spend $1.75 billion over six years, but that is a small fraction of what the Chinese are spending.

In the realm of values, the Pentagon’s initiatives are widely regarded with ethical apprehensions both within and outside the high-tech industry. In response, the Defense Innovation Board last October launched an AI Principles Project to create an ethics framework for artificial intelligence in national defense. The initiative’s first major public meeting took place this January at Harvard, where Pentagon officials met with about a dozen AI experts, some of them strong critics. Similar expert gatherings are planned at Carnegie Mellon University in March and Stanford University in April, after which the Board will release draft principles for public comment. While it is significant that this discussion is taking place on university campuses, we may hope that this fact will focus increased scholarly involvement in these issues.

The subject of values brings us back to where we started. Davidson says, from her social science perspective, that “The goal of higher education is greater than workforce readiness. It’s world readiness.” There is an additional (not alternative) consideration: that another and equally worthy goal of higher education is to prepare students for their personal maturity as human beings, in any future world, especially given as we have seen that their rapidly unfolding future world is highly unpredictable. That broader and deeper pedagogical framework is commendably included in MIT’s explicit interest in humanistic liberal education.

Liberal education, of course, invokes the deepest traditional—in fact, Classical—values of self-development and -fulfillment, as well as the newer hypermodern models increasingly dependent on artificial intelligence for a more comprehensive forward-looking synthesis. The obvious advantage of that more capacious perspective would be to ground what always and increasingly rapidly changes—history—on what never changes—fundamental human nature.

So our current Age of Paradigm Shifts is posing fundamental challenges to traditional higher education and all its institutions, which are being met by a nationwide ground-level movement searching for solutions. Several features of the movement stand out, all driven by necessity: first, that the Old Paradigm of 20th-century multiversity academicism is toast; second, that the direction of future higher education is toward more explicit commitment to students’ personal and professional development; third, that research and teaching will be much more engaged extramurally in external communities and real-world practical problem-solving; fourth, that higher education as a whole will become more explicitly responsible socially, involving more widely inclusive constituencies than ever before; fifth, that government support of higher education must increase substantially, as emergent issues compel political attention; and finally, that leaders in every institution of higher education—administrators, boards and faculty members—must now assume responsibility for guiding their institutions forward along these lines, encouraging fresh and innovative thinking and experimenting now more than ever before.

George McCully is a historian, former professor and faculty dean at higher education institutions in the Northeast, then professional philanthropist and founder and CEO of the Catalogue for Philanthropy.

Lynette Paczkowski: Colleges' limited responsibilities regarding potentially suicidal students

The Great Dome at MIT, in Cambridge, Mass.

From the New England Board of Higher Education (nebhe.org)

In 2004, then-University of New England President Sandra Featherman authored a piece for NEBEHE's New England Journal of Higher Education (NEJHE), then called Connection, headlined “Emotional Rescue” and focused on how a new generation of troubled college students was straining campus resources. Featherman, who died in April, wrote of colleges and universities scrambling to provide additional and better support services for students in need. She cited to a 2001 University of Pittsburgh survey in which 85 percent of schools reported increases in the severity of problems presenting at campus counseling centers over the preceding five years

Eight years later, a NEJHE article by Lasell College admission counselor Christopher M. Gray asked whether the proliferation of natural disasters and tragedies, such as the Sandy Hook mass shooting, were creating a new category of emotionally vulnerable college students. Specifically, he suggested that it was higher-education professionals’ “duty to aid these college-bound students as much as possible,” and urged the provision of counseling, knowledge and support. But moral duties and obligations aside, what is a higher education institution’s legal obligation to provide support services? And from a risk-management perspective, if the institution provides such services, what is its liability if the student’s mental-health issues nevertheless consume him or her?

The recent case of Nguyen v. Massachusetts Institute of Technology, et al., considered the question of whether a college or university has the obligation to protect its students from all harm at all times, including suicide. Han Nguyen was a 25-year-old graduate student at MIT when he committed suicide in 2009. His family sued the school, alleging that the school lacked sufficient support services, did not provide adequate care for its students, and failed to intervene despite knowledge of his mental state. The Massachusetts Supreme Judicial Court did not find MIT liable under the facts of the case, and within its decision, the court articulated the obligations of colleges and universities when it comes to suicide prevention.

Ultimately, the court rejected the notion that colleges and universities must act in loco parentis and keep its students safe under all circumstances. “University students are young adults, not young children. Indeed, graduate students are adults in all respects under the law. Universities recognize their students’ adult status, their desire for independence, and their need to exercise their own judgment. Consequently the modern university-student relationship is respectful of student autonomy and privacy.”

The court identified limited circumstances under which a college or university must take reasonable measures to protect a student from self-harm: where the college or university has actual knowledge of a student's suicide attempt that occurred while enrolled or recently before matriculation, or of a student's stated plans or intentions to commit suicide.

The court also addressed what would satisfy the college or university’s obligations under such circumstances. “Reasonable measures by the university to satisfy a triggered duty will include initiating its suicide prevention protocol if the university has developed such a protocol. In the absence of such a protocol, reasonable measures will require the university employee who learns of the student’s suicide attempt or stated plans or intentions to commit suicide to contact the appropriate officials at the university empowered to assist the student in obtaining clinical care from medical professionals or, if the student refuses such care, to notify the student’s emergency contact. In emergency situations, reasonable measures obviously would include contacting police, fire, or emergency medical personnel.”

The court’s decision is crucial in encouraging schools to continue to offer resources to students in need. The court not only placed finite parameters on when a school has a duty to intervene, but also identified the “complex and competing considerations” giving rise to its decision: adult students’ privacy and autonomy; the notion that non-clinicians cannot and should not be expected to probe or discern suicidal ideations that are not expressly evident; and allowing schools to take steps to acknowledge and manage the risk of campus suicide with realistic duties and responsibilities.

To be sure, the MIT student at issue had a history of presenting with academic concerns, even admitting to mental-health issues. In May 2007, he had contacted his program coordinator for assistance with test-taking problems. The program coordinator referred him to a coordinator in the MIT student disability services office, who described some of MIT’s accommodations for students with disabilities.

The student declined the accommodations. The program coordinator then referred him to MIT’s mental-health and counseling service. The student met with a psychologist on three occasions, but ultimately reported that he would be receiving treatment at Massachusetts General Hospital, not through MIT. Subsequently, the student twice met with the assistant dean in the student support office. Ultimately, the student did not seek or receive assistance from that office either. Nor did he ever communicate to any MIT employee that he had plans or intentions to commit suicide, and any prior attempts that were discussed took place well over a year before matriculation at MIT.

The plaintiff nevertheless claimed, among other things, that MIT had voluntarily assumed a duty of care. But the court found that “[a]lthough MIT voluntarily offers mental health student support services, there [was] no evidence that [the] services increased [the student’s] risk of suicide [or] that [the student] relied on [these] mental health services.”

Nothing within this case minimizes the tragedy that is the loss of a student. Nothing within this case suggests that colleges and universities can or should be ambivalent to the needs of their students or that an institution will never, under any circumstances, face liability for failing to prevent a foreseeable student suicide. Rather, the court made clear what the school’s duties and obligations are. To have decided this case any other way would have had a chilling effect on colleges and universities’ efforts to provide support and services to the increasingly large population of students in need of assistance.

Lynette Paczkowski is a partner at the Massachusetts law firm of Bowditch & Dewey, with experience representing clients from various industries including education, construction, utility, professional services, real estate and nonprofit, as well as individuals in litigation matters and litigation-avoidance strategies.

Math winners at MIT

The Stata Center at MIT, whose campus is in Cambridge, Mass., and very close to Harvard.

This is from the New England Council (newenglandcouncil.com):

"Students at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT), a New England Council member, dominated the 78th Annual William Lowell Putnam Mathematical Competition, taking 17 of the top 25 spots in a field of 4,638 test-takers from 575 institutions last December. MIT can now claim the highest rank for four out of the past five years.

"The Putnam is one of the most prestigious mathematical competitions in the U.S. and Canada, with competitors attempting to solve 12 brutally challenging problems in six hours. The highest exam score was 89 out of a possible 120 points, with only 20 percent of participants earning a score above 13. Of the five top scorers who are named Putnam Fellows, four are from MIT with a total of 38 out of the 99 top scorers being MIT undergraduates.

“'I am delighted that MIT undergraduates have again won first place in the 2017 Putnam Competition. . .This stunning performance reflects the extraordinary talent of our students and the superb coaching that they receive here. Kudos to all participants and to the Department of Mathematics,' said Michael Sipser, the Donner Professor of Mathematics and Dean of Science at MIT. The school with the first-place team receives an award of $25,000 with each first-place team member receiving $1,000. Putnam Fellows receive an award of $2,500.

At MIT, hacking away at healthcare problems

The MIT Media Lab houses researchers developing novel uses of computer technology.

This just in from the New England Council:

"Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT), a New England Council member, recently held the its fourth annual Grand Hack, a hackathon hosted with the goal of tackling some of the biggest problems in healthcare.

"The Grand Hack highlighted invisible conditions; robotics and intelligent technologies; and patient care continuum as the three broad areas in which to tackle problems. The event begins with a problem pitching session to identify challenges before dividing participants up into small groups based on their individual interests. At the end of the three-day program, the teams that presented the most innovative healthcare solutions in each of the categories received cash prizes between $750 and $1,500 in addition to the potential for funding and interest from startup incubators familiar with the event.

“'Hacking is a different lens of how people look at health care. It’s not just research or clinical study. It’s highly collaborative,' said Grand Hack Coordinator and MIT doctoral candidate, Khalil Ramadi. 'We try to help participants find elegant ways to streamline technology.'

"The New England Council thanks MIT for hosting this timely and innovative event that challenges participants to propose solutions to pressing problems facing the healthcare industry today.''

Charles Chieppo: Pay for success social programs

To its many critics, President Lyndon Johnson's War on Poverty is often described as the classic 1960s social program: a well-intentioned but naive effort that spends billions of dollars year in and year out without making much of a dent in poverty.

But imagine if government only paid social-service providers if their efforts actually yielded the desired results. That's the idea behind "pay for success" programs, also known as social impact bonds. Under this concept, businesses and/or philanthropies provide up-front money for programs to address difficult social problems. If they achieve a set of measurable outcomes within an agreed-upon time period, the funders get their investments back, plus interest. If not, government pays nothing.

Pay for success programs seem to be attracting a growing number of bipartisan fans since I wrote about them in 2014, and two new programs illustrate how implementation of the concept is becoming more sophisticated.

Last month, Connecticut Gov. Dannel Malloy, a Democrat, announced a four-year initiative to keep children from 500 families out of foster care. Social workers from the Yale Child Study Center will focus on parents with substance-abuse problems as part of an intensive effort to keep the children in their homes.

No funder has been named yet for the $12 million initiative, but several have expressed interest. If successful, the state will reimburse the up-front money plus a 5 to 6 percent interest payment. It's a pretty good deal considering that Joette Katz, commissioner of the state's Department of Children and Families, told The Washington Post that Connecticut currently pays about $350 million annually for services to children in foster care and institutions.

In South Carolina, Republican Gov. Nikki Haley recently announced a $30 million, four-year program to send registered nurses who specialize in maternal and child health into the homes of low-income pregnant women to teach them parenting skills and ways to keep their children healthy. The effort is funded by foundations and a corporation.

The Connecticut and South Carolina programs highlight the opportunity pay for success presents for prevention programs that can yield long-term savings but might not get funded through the traditional appropriations process. The South Carolina program also addresses the potentially sticky issue of determining whether a program has achieved the agreed-upon outcomes by designating an MIT research group to conduct an evaluation. Such provisions enhance the integrity and perception of pay for success.

As a model that is dependent on what funders are willing to invest in, pay for success isn't the silver bullet for addressing every stubborn and costly human-services problem. But particularly during a time when some once again seeing economic clouds looming, they can be a valuable tool for helping our neediest citizens by focusing state and local government resources on the best kinds of programs -- those that actually work.

Charles Chieppo is a research fellow at the Ash Center at Harvard's Kennedy School. This originated at governing.com.

David Warsh: Looking for a 'Jewish lunch' at Harvard

SOMERVILLE, Mass.

What propelled Massachusetts Institute of Technology economics to the top of the heap? As Bloomberg Businessweek memorably illustrated in 2012, most of the leadership arrayed against the financial crisis was educated to the task at MIT, starting with Ben Bernanke, of the Federal Reserve Board; Mervyn King, of the Bank of England, and Mario Draghi, of the European Central Bank.

That they and innumerable other talented youngsters chose MIT and turned out so well owed to the presence of two strong generations of research faculty at MIT, led in the 1970s and ’80s by Rudiger Dornbusch, Stanley Fischer, and Olivier Blanchard, and, in the ’50s and ‘60s, by Paul Samuelson, Robert Solow and Franco Modigliani.

Samuelson started it all when he bolted Harvard University in the fall of 1940 to start a program in the engineering school at the industrial end of Cambridge.

What made MIT so receptive in the first place? Was it that the engineers were substantially unburdened by longstanding Brahmin anti-Semitism, as E. Roy Weintraub argues in MIT and the Transformation of American Economics?

Or that the technologically-oriented institute was more receptive to new ideas, such as the mathematically-based “operationalizing” revolution, of which Samuelson was exemplar-in-chief, a case made in the same volume by Roger Backhouse, of the University of Birmingham?

The answer is probably both. The very founding of MIT, in 1861, enabled by the land-grant college Morrill Act, had itself been undertaken in a spirit of breakaway. First to quit Harvard for Tech was the chemist Charles W. Eliot, in 1865. (Harvard quickly hired him back to be its president.)

Harvard-trained prodigy Norbert Wiener moved to MIT in 1920 after Harvard’s mathematics department failed to appoint him; linguist Noam Chomsky left Harvard’s Society of Fellows for MIT in 1955. Historian of science Thomas Kuhn wound up at MIT, too, after a long detour via Berkeley and Princeton.

But the Harvard situation today is very different. Often overlooked is a second exodus that played an important part in bringing change about.

Turmoil at the University of at California at Berkeley, which later came to be known as the Free Speech Movement, had led a number of Berkeley professors to accept offers from Harvard: economists David Landes, Henry Rosovsky and Harvey Leibenstein; and sociologist Seymour Martin Lipset among them.

The story, in the stylized fashion in which it has often been told, is that, one of the four one day said, “You know, I kind of miss the Jewish lunch” [that they had in Berkeley].

A second said, “Why don’t we start one here?”

“How are you going to find out who’s Jewish?”

“We can’t. Some have changed their names,” said a third. Whereupon Henry Rosovsky said, “Give me the faculty list. I can figure it out.”

A month later, luncheon invitations arrived in homes of faculty members who had previously made no point of identifying one way or another. And a month after that, a group larger than the original four gathered at the first Jewish lunch at Harvard. The Jewish lunch has been going on ever since.

Rosovsky, 88, former dean of the Faculty of Arts and Sciences, and the second Jew to serve as a member of Harvard’s governing corporation (historian John Morton Blum, less open about it his Jewishness, was the first) is the sole surviving member of the original group. Last week I asked him about it.

“It was not the way things were done at Harvard. The people here were a little surprised by our chutzpah to have this kind of open Jewish lunch, reflecting, I think, the sense that the Jews were here a little bit on sufferance, I don’t think that feeling existed at Berkeley. Nobody was worried there about somebody sending an invitation to the wrong person.

“It’s a subtle thing. We left graduate school at [Harvard] for Berkeley in 1956. I wouldn’t say that Harvard was anti-Semitic, but just as in the ’30s, Berkeley was happy to take the [European] refugees, where Harvard had difficulty with this, there were notions [at Harvard] of public behavior, of what was fitting. Berkeley was a public university, nobody thought twice about their lunch.”

Rosovsky’s wife, Nitza, an author who prepared an extensive scholarly exhibition on "The Jewish Experience at Harvard and Radcliffe'' for the university’s 350th anniversary, in 1986, remembered that there were surprising cases. Merle Fainsod, the famous scholar of Soviet politics who grew up in McKee’s Rocks, Pa., asked her one night at dinner if she knew his nephew, Yigael Yadin? “Apparently this was the first time he ever said in public that he was Jewish.” Yadin was a young archaeologist who served as head of operations of the Israeli Defense Forces during its 1948 war and later translated the Dead Sea Scrolls.

Rosovsky’s exhibition catalog tells the story in a strong narrative. Perhaps a dozen Jews graduated in Harvard’s first 250 years. But as a professor, then as president of the university, A. Lawrence Lowell watched the proportion of Jewish undergraduates rise from 7 percent of freshmen in 1900 to 21.5 in 1922. Jews constituted 27 percent of college transfers, 15 percent of special students, 9 percent of Arts and Sciences graduate students, and 16 percent of the Medical School. Harvard was deemed to have a “Jewish problem,” which was addressed by a system of quotas lasting into the 1950s.

The most outspoken anti-Semite in the Harvard Economics Department at the time that Samuelson left was Harold Burbank. Burbank died in 1951. Some 20 years later, it fell to Rosovsky, in his capacity as chairman of the economics department, to dispose of the contents of his Cambridge house. It turned out that Burbank had left everything to Harvard – enough to ultimately endow a couple of professorships.

So it was was Rosovsky, by then the faculty dean, who persuaded Robert Fogel – a Jew and a former Communist married to an African-American woman, who he hired away from the University of Chicago – to become the first Harold Hitchings Burbank Professor of Political Economy. “He was the only one who didn’t know the history,” said Rosovsky. Fogel went on to share a Nobel prize in economics.

It is the hardest struggles that command the greatest part of our attention. But between Montgomery, Ala., in 1955-56, when the Civil Rights Movement for African-Americans really got going, and the Stonewall Inn riot, in New York, in 1969, when homosexuals' rights started to get a lot of attention, a great many groups graduated to “whiteness,” as Daniel Rodgers puts it in Age of Fracture – including Jews, Irish Catholics. and, of course, women.

Whatever it was that MIT started, Harvard and all other major universities soon enough accelerated – in economics as well as the dismantling of stereotypes of race and gender. By the time that comparative literature professor Ruth Wisse asserted that anti-Semitism had brought down former Harvard President Lawrence Summers, virtually no one took her seriously.

David Warsh, a longtime economic historian and financial journalist, is proprietor of economicprincipals.com.

.

David Warsh: MIT: The 'Duffy's Tavern' of American economics

SOMERVILLE, Mass.

As something of beat reporter, I have half a dozen good stories about economics at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology in various stages of preparation. So what to make of a recent book, #mit and the Transformation of American Economics (Duke, 2014).

I love it, naturally. Not only does it contribute fundamentally to our knowledge of how Paul Samuelson and Robert #solow at MIT more or less invented the field we call macroeconomics and came to dominate the field for a time, but it illuminates the difference between history and journalism.

Transformation is the hardbound annual supplement to the journal History of Political Economy, which is published quarterly by Duke University Press. Each year a research conference assembles an array of scholars writing on a single broad topic; 18 months later, suitably edited, their papers appear in book form. The topic of the conference to be held next month is “Economizing Mind, 1870-2015: When Economics and Psychology Met… or Didn’t.”

Each volume is in conception the creature of an organizing editor, in this case, E. Roy Weintraub, a Duke professor of economics who, one way or another has been on the trail of the MIT story for nearly 40 years. He is the author of, among other books, How Economics Became a Mathematical Science, and last year, with Till Düppe, of Finding Equilibrium: Arrow, Debreu, McKenzie and the Problem of Scientific Credit (Princeton, 2015).

In an introduction, Weintraub lists six competing explanations that have been advanced to account for MIT's rise to the top of the economics profession:

The oldest narrative and most familiar invokes a Keynesian Revolution, swift transformation in which a mimeographed version of The General Theory of Employment Interst , carried to Harvard by Canadian graduate student Robert Bryce, converted first a circle of graduate students, then Harvard Prof. Alvin Hansen, and finally wunderkind Paul Samuelson, who promptly decamped to the technological institute down the street. There is no better account of this version than The Coming of Keynesiaism to America: Conversations with the Founders of Keynesian Economics (Edward Elgar, 1996), edited by David Colander, of Middlebury College, and Harry Landreth, of Centre College.

A second narrative emerged in From Interwar Pluralism to Postwar Neoclassicism a HOPE conference volume from 1998 edited by Mary Morgan, of the London School of Economics, and Malcolm Rutherford, of the University of Victoria. The theories of demand, production and the firm had all been matters of contention in the 1930s, but by the mid-1950s, Weintraub writes, all were settled chapters in graduate and intermediate microeconomic textbooks. How were they thus “stabilized?” It couldn’t have been the highly literary Keynes. Instead it was the new importance that others attached to the role of models and measurement, a thesis elaborated by Morgan in The World in the Model: How Economists Work and Think(Cambridge, 2012) and further illuminated by Weintraub.

A third set of stories emphasizes the effects of World War II: the United States; post-war hegemony overwhelmed various national traditions, especially in Britain and Vienna. Only the U.S. had the resources to educate, train and employ economists, so naturally the science came to be spoken with an American accent. Roger Backhouse, of the University of Birmingham and the University of Rotterdam, editor, with Philippe Fontaine, of The History of the Social Sciences since 1945, (Cambridge, 20120), contributes an essay to the current volume, ”MIT and the Other Cambridge,” describing the 15-year battle known as the “capital controversy” through which the American Cambridge took control.

A fourth interpretation contends that the Cold War turned economics and game theory into a Procrustean bed for purposes of exercising social control. None has gone further down this road than Philip Mirowski, of the University of Notre Dame, in Machine Dreams: Economics Becomes a Cyborg Science, (Cambridge, 2002), but Mirowski is not represented in the current volume. Instead essay on the history of operations research, by William Thomas, of History Associates, Rockville, Md., is said to refute Mirowski’s central claim.

Yet another version puts demand for economists; services at the heart of the story, first at MIT, where interest in the “new economics” was greatest, then at several other schools of business and engineering, especially Pittsburgh’s Carnegie Institute of Technology (today Carnegie Mellon University), as described in The Roots, Rituals and Rhetoric of Change: North American Business Schools After the Second World War (Stanford, 2011), by Mie Augier, of the Naval Post Graduate School, and James March, of Stanford University. The role of the GI Bill of Rights in re-shaping U.S. higher education plays a central role here.

A sixth factor, advanced by Weintraub in the Transformation volume, argues that the rise of MIT stemmed from its willingness to appoint Jewish economists to senior positions, starting with Samuelson himself. Anti-Semitism was common in American universities on the eve of World War II, and while most of the best universities had one Jew or even two on their faculties of arts and sciences, to demonstrate that they were free of prejudice, none showed any willingness to appoint significant numbers until the flood of European émigrés after World War I began to open their doors.

MIT was able to recruit its charter faculty – Maurice Adelmam, Max Millikan, Eugene Rostow, Paul Rosenstein-Rodin, Solow, Evsey Domar and Franco Modigliani were Jews – “not only because of Samuelson’s growing renown,” writes Weintraub, “…but because the department and university were remarkably open to the hiring of Jewish faculty at a time when such hiring was just beginning to be possible at Ivy Leaguer Universities,”.

Many essays stand out. Backhouse nails down the details of Samuelson’s decision to sign on at MIT. Harro Maas, of Utrecht University, describes the efforts of the University of Chicago to lure Samuelson in the later 1940s. Perry Mehrling, of Barnard College, contributes a perspicacious essay describing the difficulty the MIT tradition, with its emphasis on the general equilibrium of a system of prices, had in coming to grips with the role of money, which the tradition customarily has abstracted away. And Beatrice Cherrier, of the University of Caen, provides a lively overview of the history of the department to begin the volume.

At one point Cherrier quotes a 1967 letter Solow wrote to his colleague Franklin Fisher, who had reported from Israel the view there that the MIT department is too committed to orthodoxy that Samuelson and Solow had devised to be able to recognize promising future developments, especially in theory. Solow wrote, “Peter Diamond and Peter Temin will help a lot. Miguel Sidrauski may develop very well…. The department has agreed to go for another econometrician, if we can find a young star. .. I think the prospects are good that we can remain the Duffy’s Tavern of economics, where the elite meet to eat.” The reference is to a popular radio show of the 1940s, an adumbration of the sentimental 1980s television series Cheers.

Fisher was right; Solow was wrong (though Cherrier doesn’t say so). Leadership in theory was about to pass from MIT, though its preeminence in applied economics would soon become apparent. But Solow’s metaphor is especially well chosen, and not just because of the gemütlichkeit of the customary table upstairs at the MIT faculty club, where the economists met most days for lunch.

The broadcast of Duffy’s Tavern always began the same way: a rendition of “When Irish Eyes are Smiling'' interrupted by the ringing of a phone: "Hello, Duffy's Tavern, where the elite meet to eat. Archie the manager speakin'. Duffy ain't here—oh, hello, Duffy."

The centerpierce of Transformation is an appreciation of Solow by Verena Halsmayer, of the University of Vienna. In “From Exploratory Modeling to Technical Expertise: Solow’s Growth Model as a Multipurpose Design,” Halsmayer makes a serious attempt to rescue Solow – the manager of the MIT economics department for 30 years – from the shadow of the brilliant Samuelson and evaluate the younger man’s principal contribution, the Solow model of economic growth.

It was a farther-reaching development than is generally understood, she argues, nothing less than a replicable “design” for a specific way of doing economics. a relatively unencumbered means of combining theory with measurement so as to interrogate the real world with “high hopes of producing useful and practical knowledge for economic governance.” As his student George Akerlof once put it, Solow began the process of turning the word “model” into a verb.

Transformation is the latest draft of history, a promising start on what promises to be a very complicated process. More will follow relatively quickly: Michael Weinstein, an MIT PhD who for many years was a member of the editorial board of The New York Times, is completing a book-length essay on Samuelson. Backhouse has begun a full-scale biography. Much more remains to be done including a proper biography of Solow.

Yet for all the value of careful history, it remains, by definition, a rear-view mirror That is why we have journalism, too.

David Warsh, a longtime economic historian and financial journalist, is proprietor of economicprincipals.com.

Todd Larsen: Ditch Md. LNG unit and build wind farm

WASHINGTON

Shortly before Congress left for its long summer vacation, Sen. Barbara Mikulski tried to block a 150-megawatt wind farm.

The Maryland Democrat’s move would delay Pioneer Green Energy’s construction of the project in her own state until an independent study from the Massachusetts Institute of Technology concerning the effects of wind turbines on naval radar testing at the Patuxent River Naval Base is completed.

While it’s understandable that Mikulski wouldn’t want anything to interfere with a major military installation, what makes her move inexplicable is that Pioneer Green Energy is already working with the base to ensure that its wind farm won’t disrupt the base’s radar, as required by law.

Technically, she’s seeking a delay via language inserted in a Department of Defense appropriations bill. But the postponement would potentially push the project’s timeline out past the qualifying deadline for tax credits. That could effectively end the project, no matter what the MIT study finds.

This is just one of many attempts to kill wind farms. Opponents have lodged about 50 lawsuits in this country and around the world against wind projects because they allegedly cause “wind turbine syndrome,” a discredited condition first described by a pediatrician in 2009. The alleged symptoms of the syndrome range from headaches to sleeplessness to forgetfulness. These symptoms haven’t held up in court: 48 of the 49 suits have been dismissed.

Wind power foes also object to clusters of turbines for aesthetic reasons and their potential to reduce property values. This concern doesn’t pass the sniff test either. An extensive Energy Department study found no “consistent, measurable, and significant effect on the selling prices of nearby homes.”

Other opponents fear that turbines will kill tons of birds. In reality, wind farms aren’t nearly as deadly to our feathered friends as office buildings and cats, just to name two major avian killers. And when was the last time you heard about someone trying to ban buildings and cats to save birds?

Even when the opposition to wind power fails — which it often does — the resistance hurts wind farm developers. It also sends a chilling message to an industry that lacks the deep pockets of fossil-fuel companies and lobbyists. And those oil, gas, and coal special interests are funding many of the attacks on wind and renewable energy in the first place.

What makes these assaults on wind particularly troubling is that the United States is rapidly moving forward with several projects that will ramp up domestic oil and gas production.

In fact, the United States is now on track to be the world’s top oil and natural-gas producer, and is a net oil exporter for the first time since 1995.

Much of this increased oil and gas output is being extracted through hydraulic fracturing, or “fracking.” And the toll of this method is becoming increasingly clear. From contaminated drinking water, to polluted air, to ruined infrastructure from endless trucks carting water, fracking is leaving its devastating mark on towns across the country.

Fracking, and fossil-fuel extraction in general, also contributes to boom-and-bust economies that siphon most economic benefits out of local communities, which are then left to deal with the resulting devastation on their own.

Maryland faces the same energy choices as the nation overall. While Mikulski’s legislative maneuvers may kill a major wind farm, Dominion Energy is working to build a $3.8 billion liquefied-natural-gas-export terminal on Maryland’s Eastern Shore called Cove Point. That facility would endanger local communities, increase pollution, and ramp up fracking in nearby states — potentially leading to fracking in Maryland itself — while boosting natural-gas prices in the U.S. market.

A Maryland judge recently ruled that zoning laws and the Maryland Constitution were violated in permitting Cove Point, which will slow the project. That gives the state and Cove Point’s Wall Street backers time to heed the concerns expressed by opponents of this dangerous facility.

Ideally, investors could shift the $3.8 billion going to Cove Point to wind power. That move would increase East Coast wind production by 50 percent, and create over 7,500 jobs. It would also serve as a model for the country in how to invest in a clean energy future.

Todd Larsen directs Green America’s (GreenAmerica.org) responsibility division. This was distributed via OtherWords.org.

Addendum from Robert Whitcomb: People rarely think of the massive number of birds killed by air, water and soil pollution from fossil fuel.

Using coastal water exchange for power

From ecoRI news staff. Thank you.

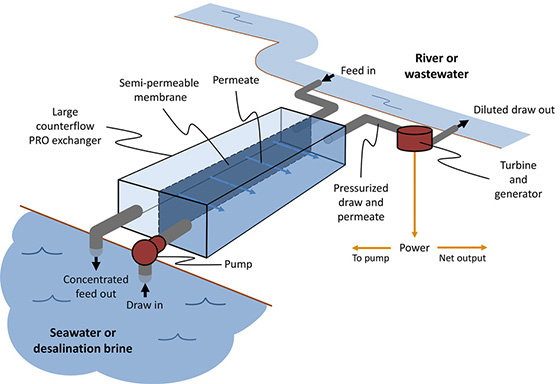

Graphic by Leonardo Banchik/Elsevier B.V.

CAMBRIDGE

Where the river meets the sea, there is the potential to harness a significant amount of renewable energy, according to a team of mechanical engineers at MIT.

The researchers evaluated an emerging method of power generation called pressure retarded osmosis (PRO), in which two streams of different salinity are mixed to produce energy. In principle, a PRO system would take in river water and seawater on either side of a semi-permeable membrane. Through osmosis, water from the less-salty stream would cross the membrane to a prepressurized saltier side, creating a flow that can be sent through a turbine to recover power.

The MIT team has developed a model to evaluate the performance and optimal dimensions of large PRO systems. In general, the researchers found that the larger a system’s membrane, the more power can be produced, but only up to a point. Interestingly, 95 percent of a system’s maximum power output can be generated using only half or less of the maximum membrane area.

Leonardo Banchik, a graduate student in MIT’s Department of Mechanical Engineering, said reducing the size of the membrane needed to generate power would, in turn, lower much of the upfront cost of building a PRO plant.

“People have been trying to figure out whether these systems would be viable at the intersection between the river and the sea,” he said. “You can save money if you identify the membrane area beyond which there are rapidly diminishing returns.”

Banchik and his colleagues have also been able to estimate the maximum amount of power produced, given the salt concentrations of two streams. The greater the ratio of salinities, the more power can be generated. For example, they found that a mix of brine, a byproduct of desalination, and treated wastewater can produce twice as much power as a combination of seawater and river water.

Based on his calculations, Banchik said a PRO system could potentially power a coastal wastewater treatment plant by taking in seawater and combining it with treated wastewater to produce renewable energy.

“Here in Boston Harbor, at the Deer Island wastewater treatment plant, where wastewater meets the sea … PRO could theoretically supply all of the power required for treatment,” Banchik said.

He and John Lienhard, professor of water and food at MIT, along with Mostafa Sharqawy of King Fahd University of Petroleum and Minerals, in Saudi Arabia, report their results in the Journal of Membrane Science.

The team based its model on a simplified PRO system in which a large semi-permeable membrane divides a long rectangular tank. One side of the tank takes in pressurized seawater, while the other side takes in river water or wastewater. Through osmosis, the membrane lets through water, but not salt. As a result, fresh water is drawn through the membrane to balance the saltier side.

“Nature wants to find an equilibrium between these two streams,” Banchik said.

As fresh water enters the saltier side, it becomes pressurized while increasing the flow rate of the stream on the salty side of the membrane. This pressurized mixture exits the tank, and a turbine recovers energy from this flow.

Banchik said that while others have modeled the power potential of PRO systems, these models are mostly valid for laboratory-scale systems that incorporate “coupon-sized” membranes. Such models assume that the salinity and flow of incoming streams is constant along a membrane. Given such stable conditions, these models predict a linear relationship: the bigger the membrane, the more power generated.

But in flowing through a system as large as a power plant, Banchik said the streams’ salinity and flux will naturally change. To account for this variability, he and his colleagues developed a model based on an analogy with heat exchangers.

“Just as the radiator in your car exchanges heat between the air and a coolant, this system exchanges mass, or water, across a membrane,” Banchik said. “There’s a method in literature used for sizing heat exchangers, and we borrowed from that idea.”

The researchers came up with a model with which they could analyze a wide range of values for membrane size, permeability and flow rate. With this model, they observed a nonlinear relationship between power and membrane size for large systems. Instead, as the area of a membrane increases, the power generated increases to a point, after which it gradually levels off. While a system may be able to produce the maximum amount of power at a certain membrane size, it could also produce 95 percent of the power with a membrane half as large.

Still, if PRO systems were to supply power to Boston’s Deer Island treatment plant, the size of a plant’s membrane would be substantial — at least 2.5 million square meters, which Banchik noted is the membrane area of the largest operating reverse osmosis plant in the world.

“Even though this seems like a lot, clever people are figuring out how to pack a lot of membrane into a small volume,” Banchik said. “For example, some configurations are spiral-wound, with flat sheets rolled up like paper towels around a central tube. It’s still an active area of research to figure out what the modules would look like.

“Say we’re in a place that could really use desalinated water, like California, which is going through a terrible drought. They’re building a desalination plant that would sit right at the sea, which would take in seawater and give Californians water to drink. It would also produce a saltier brine, which you could mix with wastewater to produce power. More research needs to be done to see whether it can be economically viable, but the science is sound.”