Wildlife, ecology and the next pandemic

Sign over I-93 in Boston warning of COVID-19 travel restrictions in Massachusetts

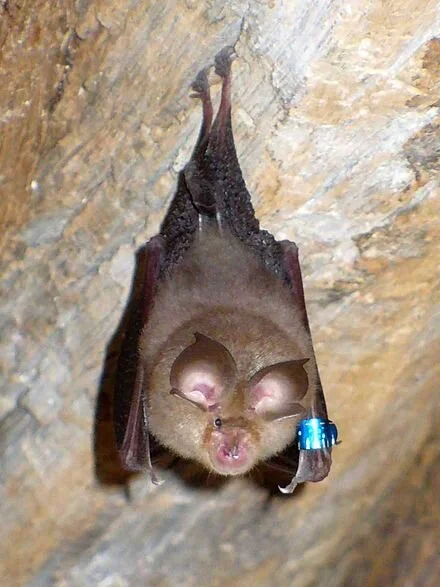

A horseshoe bat, seen as likely source of COVID-19

As the COVID-19 pandemic heads for a showdown with vaccines it’s expected to lose, many experts in the field of emerging infectious diseases are already focused on preventing the next one.

They fear another virus will leap from wildlife into humans, one that is far more lethal but spreads as easily as SARS-CoV-2, the strain of coronavirus that causes COVID-19. A virus like that could change the trajectory of life on the planet, experts say.

“What keeps me up at night is that another coronavirus like MERS, which has a much, much higher mortality rate, becomes as transmissible as covid,” said Christian Walzer, executive director of health at the Wildlife Conservation Society. “The logistics and the psychological trauma of that would be unbearable.”

SARS-CoV-2 has an average mortality rate of less than 1%, while the mortality rate for Middle East respiratory syndrome, or MERS — which spread from camels into humans — is 35%. Other viruses that have leapt the species barrier to humans, such as bat-borne Nipah, have a mortality rate as high as 75%.

“There is a huge diversity of viruses in nature, and there is the possibility that one has the Goldilocks characteristics of pre-symptomatic transmission with a high fatality rate,” said Raina Plowright, a virus researcher at the Bozeman Disease Ecology Lab, in Montana. (COVID-19 is highly transmissible before the onset of symptoms but fortunately is far less lethal than several other known viruses.) “It would change civilization.”

That’s why in November the German Federal Foreign Office and the Wildlife Conservation Society held a virtual conference called One Planet, One Health, One Future, aimed at heading off the next pandemic by helping world leaders understand that killer viruses like SARS-CoV-2 — and many other less deadly pathogens — are unleashed on the world by the destruction of nature.

With the world’s attention gripped by the spread of the coronavirus, infectious disease experts are redoubling their efforts to show the robust connection between the health of nature, wildlife and humans. It is a concept known as One Health.

While the idea is widely accepted by health officials, many governments have not factored it into policies. So the conference was timed to coincide with the meeting of the world’s economic superpowers, the G20, to urge them to recognize the threat that wildlife-borne pandemics pose, not only to people but also to the global economy.

The Wildlife Conservation Society — America’s oldest conservation organization, founded in 1895 — has joined with 20 other leading conservation groups to ask government leaders “to prioritize protection of highly intact forests and other ecosystems, and work in particular to end commercial wildlife trade and markets for human consumption as well as all illegal and unsustainable wildlife trade,” they said in a recent press release.

Experts predict it would cost about $700 billion to institute these and other measures, according to the Wildlife Conservation Society. On the other hand, it’s estimated that covid-19 has cost $26 trillion in economic damage. Moreover, the solution offered by those campaigning for One Health goals would also mitigate the effects of climate change and the loss of biodiversity.

The growing invasion of natural environments as the global population soars makes another deadly pandemic a matter of when, not if, experts say — and it could be far worse than covid. The spillover of animal, or zoonotic, viruses into humans causes some 75% of emerging infectious diseases.

But multitudes of unknown viruses, some possibly highly pathogenic, dwell in wildlife around the world. Infectious disease experts estimate there are 1.67 million viruses in nature; only about 4,000 have been identified.

SARS-CoV-2 likely originated in horseshoe bats in China and then passed to humans, perhaps through an intermediary host, such as the pangolin — a scaly animal that is widely hunted and eaten.

While the source of SARS-CoV-2 is uncertain, the animal-to-human pathway for other viral epidemics, including Ebola, Nipah and MERS, is known. Viruses that have been circulating among and mutating in wildlife, especially bats, which are numerous around the world and highly mobile, jump into humans, where they find a receptive immune system and spark a deadly infectious disease outbreak.

“We’ve penetrated deeper into eco-zones we’ve not occupied before,” said Dennis Carroll, a veteran emerging infectious disease expert with the U.S. Agency for International Development. He is setting up the Global Virome Project to catalog viruses in wildlife in order to predict which ones might ignite the next pandemic. “The poster child for that is the extractive industry — oil and gas and minerals, and the expansion of agriculture, especially cattle. That’s the biggest predictor of where you’ll see spillover.”

When these things happened a century ago, he said, the person who contracted the disease likely died there. “Now an infected person can be on a plane to Paris or New York before they know they have it,” he said.

Meat consumption is also growing, and that has meant either more domestic livestock raised in cleared forest or “bush meat” — wild animals. Both can lead to spillover. The AIDS virus, it’s believed, came from wild chimpanzees in central Africa that were hunted for food.

One case study for how viruses emerge from nature to become an epidemic is the Nipah virus.

Nipah is named after the village in Malaysia where it was first identified in the late 1990s. The symptoms are brain swelling, headaches, a stiff neck, vomiting, dizziness and coma. It is extremely deadly, with as much as a 75% mortality rate in humans, compared with less than 1% for SARS-CoV-2. Because the virus never became highly transmissible among humans, it has killed just 300 people in some 60 outbreaks.

One critical characteristic kept Nipah from becoming widespread. “The viral load of Nipah, the amount of virus someone has in their body, increases over time” and is most infectious at the time of death, said the Bozeman lab’s Plowright, who has studied Nipah and Hendra. (They are not coronaviruses, but henipaviruses.) “With SARS-CoV-2, your viral load peaks before you develop symptoms, so you are going to work and interacting with your family before you know you are sick.”

If an unknown virus as deadly as Nipah but as transmissible as SARS-CoV-2 before an infection was known were to leap from an animal into humans, the results would be devastating.

Plowright has also studied the physiology and immunology of viruses in bats and the causes of spillover. “We see spillover events because of stresses placed on the bats from loss of habitat and climatic change,” she said. “That’s when they get drawn into human areas.” In the case of Nipah, fruit bats drawn to orchards near pig farms passed the virus on to the pigs and then humans.

“It’s associated with a lack of food,” she said. “If bats were feeding in native forests and able to nomadically move across the landscape to source the foods they need, away from humans, we wouldn’t see spillover.”

A growing understanding of ecological changes as the source of many illnesses is behind the campaign to raise awareness of One Health.

One Health policies are expanding in places where there are likely human pathogens in wildlife or domestic animals. Doctors, veterinarians, anthropologists, wildlife biologists and others are being trained and training others to provide sentinel capabilities to recognize these diseases if they emerge.

The scale of preventive efforts is far smaller than the threat posed by these pathogens, though, experts say. They need buy-in from governments to recognize the problem and to factor the cost of possible epidemics or pandemics into development.

“A road will facilitate a transport of goods and people and create economic incentive,” said Walzer, of the Wildlife Conservation Society. “But it will also provide an interface where people interact and there’s a higher chance of spillover. These kinds of costs have never been considered in the past. And that needs to change.”

The One Health approach also advocates for the large-scale protection of nature in areas of high biodiversity where spillover is a risk.

Joshua Rosenthal, an expert in global health with the Fogarty International Center at the National Institutes of Health, said that while these ideas are conceptually sound, it is an extremely difficult task. “These things are all managed by different agencies and ministries in different countries with different interests, and getting them on the same page is challenging,” he said.

Researchers say the clock is ticking. “We have high human population densities, high livestock densities, high rates of deforestation — and these things are bringing bats and people into closer contact,” Plowright said. “We are rolling the dice faster and faster and more and more often. It’s really quite simple.”

Jill Richardson: How do we get skeptics to get COVID shots?

U.S. airman Ramón Colón-López receives Pfizer COVID-19 vaccine at Walter Reed National Military Medical Center this month.

Via OtherWords.org

With the new COVID-19 vaccine available, Dr. Anthony Fauci says Americans can begin to achieve herd immunity by next summer. Herd immunity occurs when so many people are immune to the virus that it can’t spread, because an infected person won’t have anyone left to spread it to.

Yet as of last month, four in ten Americans said they definitely or probably won’t get the vaccine (although about half of that group said they would consider it once a vaccine became available and they could get more information about it).

Why, after living in quarantine for almost 10 months while the economy and our mental health crashes around us, after over 300,000 Americans are dead, is getting the vaccine even a question?

There are two ways to approach this question. The first is to dismiss it: Call vaccine skeptics derogatory names, post memes on social media about how stupid they are, and make rules requiring the vaccine.

The second way to approach the question is to try to understand vaccine skepticism in order to address Americans’ concerns.

Sociologist Jennifer Reich tied vaccine refusal to messages that treat health like a personal project, in which consumers must exercise their own discretion, and a culture of individualism in a world where there is not enough of anything to go around — jobs, money, health care, etc.

In this view, everyone must look out for themselves so they can get ahead, and that’s more important than doing your part to achieve herd immunity for our collective wellbeing.

Reich’s research on anti-vaxxers comes from before the current pandemic. She studied parents who refused to vaccinate their children for preventable diseases like measles. But it’s still worth considering in this new context. Reich believes it is unsurprising that some people do treat vaccines like a consumer choice and disregard that when they decline a vaccine, they endanger others too.

Another take on COVID vaccine refusal comes from Zakiya Whatley and Titilayo Shodiya, who are both women of color with PhDs in natural sciences. They focus on Black, Latinx and indigenous communities, who often distrust doctors. Their suspicion is not unfounded, given how much racism in medicine has harmed people of color, historically and in the present.

Scientists hold the power to define what is true and what is not in a way that non-scientists do not. Consider the power relations within medicine: When a patient goes to the doctor because they are ill, the doctor assesses their symptoms, makes a diagnosis, and prescribes a treatment.

Scientists determine what is recognized as a diagnosis and which treatments are available. Powerful financial interests (like pharmaceutical and insurance companies) play a major role too. The patient’s power is more limited: they can look up their symptoms on WebMD, accept or refuse the treatment prescribed, or go to a different doctor.

Sometimes lay people react to being on the less powerful end of the relationship by simply refusing to believe scientists. They might resist by embracing conspiracy theories or “barstool biology” that uses the language of science but not the scientific method.

Natural scientists have done their part by creating vaccines that are safe and highly effective. To get people to take the vaccine, we need social science. We must learn how to rebuild trust with people who have lost it. And we will do that by listening to them and understanding them, not by calling them stupid.

Jill Richardson, a sociologist, is an OtherWords.org columnist.

Headquarters of a COVID-19 vaccine inventor and maker, Moderna, in Cambridge, Mass. Greater Boston is one of the world’s centers of biotechnology.

New study says mask-wearing most important factor in cutting chance of getting COVID-19 during air travel

A Delta Airlines plane being disinfected between flights

From The New England Council (newenglandcouncil.com)

BOSTON

“Researchers at the Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health have completed a comprehensive, gate-to-gate study on how to greatly reduce the chances of COVID-19 transmission during air travel.

“The study concludes that universal mask-wearing, rigorous cleaning protocols and high-end air filtration systems lower the risk of COVID-19 transmission to minimal levels. The study found that mask-wearing among passengers and crew is the most important factor in reducing risk during air travel. The researchers also found that the use of high-efficiency particulate air (HEPA) filters is extremely effective in removing harmful airborne particles. Ultimately, diligently engaging in this multi-layered approach results in a substantially lowered risk of COVID-19 transmission during air travel in comparison to other activities.

“‘The risk of COVID-19 transmission onboard aircraft [is] below that of other routine activities during the pandemic, such as grocery shopping or eating out,’ the Harvard researchers concluded. 'Implementing these layered risk mitigation strategies…requires passenger and airline compliance [but] will help to ensure that air travel is as safe or substantially safer than the routine activities people undertake during these times.’

“Read more from the National Preparedness Initiative report.’’

Linda Gasparello: What’s good for us can be very bad for wildlife

Remains of an albatross killed by ingesting plastic pollution.

WEST WARWICK, R.I.

When I lived in Manhattan, I pursued an unusual pastime. I started it to avoid eye contact with Unification Church members who peddled flowers and their faith on many street corners in the 1970s. If a Moonie (as a church member was derisively known) were to approach me, I’d cast my eyes down to the sidewalk, where I’d see things that would set my mind wandering.

In the winter, I’d see lone gloves and mittens. On the curb in front of La Cote Basque on East 55th Street, the luxe French restaurant where Truman Capote dined with the doyennes of New York’s social scene, before dishing on them in his unfinished novel, Answered Prayers, I saw a black leather glove with a gold metal “F” sewn on the cuff. I coveted such a Fendi pair, eyeing them at the glove counter at Bergdorf Goodman, but not buying them – they cost about a third of my Greenwich Village studio apartment’s monthly rent in the late 1970s. On the sidewalk on Fifth Avenue, in front of an FAO Schwartz window, I saw a child’s mitten, expertly knit in a red-and-white Norwegian pattern that I never had the patience to follow. I wondered whether the child dropped the mitten after removing it to point excitedly to a toy in the window.

In the summer, I’d see pairs of sunglasses and single sneakers on the sidewalks, things that had fallen out of weekenders’ pockets and bags. It wasn’t unusual for me to see pantyhose. Working women in Manhattan, in my time there, could wear a short-sleeved wrap dress – the one designed by Diane von Furstenberg was the working woman’s boilersuit -- in the summer, but they’d better have put on pantyhose, or packed a pair in their pocketbooks or tote bags. The pantyhose would fall out of them and roll like tumbleweed along the avenues.

One summer morning on Perry Street, near where I lived, I saw a long, black zipper. It looked like a black snake had slithered out of a drain grate on the street and was warming itself on the asphalt, its white belly gleaming in the sun.

Now when I walk on a city sidewalk, I still look down, not to pursue my pastime but to preserve myself from tripping and falling on stuff. I sometimes see interesting litter, but mostly I see single-use and reusable face masks.

This fall, as I walked on the waterfront promenade along Rondout Creek in Kingston, N.Y., I saw a single-use mask swirling in the wind with the fallen leaves. I grabbed the mask and deposited it in a trash can, worried that it would fall into the creek, ensnarling the waterfowl and the fish.

In the COVID-19 crisis, masks have been lifesavers. But masks, especially single-use, polypropylene surgical masks, have been killing marine wildlife and devastating ecosystems.

Billions of masks have been entering our oceans and washing onto our beaches when they are tossed aside, where waste-management systems are inadequate or nonexistent, or when these systems become overwhelmed because of increased volumes of waste.

A new report from OceansAsia, a Hong Kong-based marine conservation organization, estimates that 1.56 billion masks will have entered the oceans in 2020. This will result in an additional 4,680 to 6,240 metric tons of marine plastic pollution, says the report, entitled “Masks on the Beach: The impact of COVID-19 on Marine Plastic Pollution.”

Single-use masks are made from a variety of meltdown plastics and are difficult to recycle, due to both composition and risk of contamination and infection, the report points out. These masks will take as long as 450 years to break down, slowly turning into microplastics ingested by wildlife.

“Marine plastic pollution is devastating our oceans. Plastic pollution kills an estimated 100,000 marine mammals and turtles, over a million seabirds, and even greater numbers of fish, invertebrates and other animals each year. It also negatively impacts fisheries and the tourism industry and costs the global economy an estimated $13 billion per year,” according to Gary Stokes, operations director of OceansAsia.

The report recommends that people wear reusable masks, and to dispose of all masks properly.

I hope that everyone will wear them for the sake of their own and others’ health, and that I won’t see them lying on sidewalks on my strolls, or on beaches, where they are a sorry sight.

Linda Gasparello is co-host and producer of White House Chronicle, on PBS. Her email is whchronicle@gmail.com and she’s based in Rhode Island and Washington, D.C.

Victoria Knight: Those tough COVID Christmas travel decisions

Our Lady of the Airways Chapel .at Logan International Airport, in Boston. You’d think that it would get crowded these days, given the new risks of travel. The chapel is the oldest airport chapel in the United States, opening originally in 1951 in another part of the airport.

Vivek Kaliraman, who lives in Los Angeles, has celebrated every Christmas since 2002 with his best friend, who lives in Houston. But, this year, instead of boarding an airplane, which felt too risky during the COVID pandemic, he took a car and plans to stay with his friend for several weeks.

The trip — a 24-hour drive — was too much for one day, though, so Kaliraman called seven hotels in Las Cruces, N.M. — which is about halfway — to ask how many rooms they were filling and what their cleaning and food-delivery protocols were.

“I would call at nighttime and talk to one front desk person and then call again at daytime,” said Kaliraman, 51, a digital health entrepreneur. “I would make sure the two different front desk people I talked to gave the same answer.”

Once he arrived at the hotel he’d chosen, he asked for a room that had been unoccupied the night before. And even though it got cold that night, he left the window open.

Scary Statistics Trigger Strict Precautions

Many Americans, like Kaliraman, who did ultimately make it to Houston, are still planning to travel for the December holidays, despite the nation’s worsening coronavirus numbers.

Last week, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention reported that the weekly COVID hospitalization rate was at its highest point since the beginning of the pandemic. More than 283,000 Americans have died of COVID-19. Public health officials are bracing for an additional surge in cases resulting from the millions who, despite CDC advice, traveled home for Thanksgiving, including the 9 million who passed through airports Nov. 20-29. Hospital wards are quickly reaching capacity. In light of all this, health experts are again urging Americans to stay home for the holidays.

For many, though, travel comes down to a risk-benefit analysis.

According to David Ropeik, author of the book How Risky Is It, Really? and an expert in risk perception psychology, it’s important to remember that what’s at stake in this type of situation cannot be exactly quantified.

Our brains perceive risk by looking at the facts of the threat — in this case, contracting or transmitting COVID-19 — and then at the context of our own lives, which often involves emotions, he said. If you personally know someone who died of COVID-19, that’s an added emotional context. If you want to attend a wedding of loved family members, that’s another kind of context.

“Think about it like a seesaw. On one side are all the facts about COVID-19, like the number of deaths,” said Ropeik. “And then on the other side are all the emotional factors. Holidays are a huge weight on the emotional side of that seesaw.”

The people we interviewed for this story said they understand the risk involved. And their reasons for going home differed. Kaliraman likened his journey to see his friend as an important ritual — he hasn’t missed this visit in 19 years.

What’s clear is that many aren’t making the decision to travel lightly.

For Annette Olson, 56, the risk of flying from Washington, D.C., to Tyler, Texas, felt worth it because she needed to help take care of her elderly parents over the holidays.

“In my calculations, I would be less of a risk to them than for them to get a rotating nurse that comes to the house, who has probably worked somewhere else as well and is repeatedly coming and going,” said Olson. “Once I’m here, I’m quarantined.”

Now that she’s with her parents, she’s wearing a mask in common areas of the house until she gets her COVID test results back.

Others plan on quarantining for several weeks before seeing family members — even if, as in Chelsea Toledo’s situation, the family she hopes to see is only an hour’s drive away.

Toledo, 35, lives in Clarkston, Ga., and works from home. She pulled her 6-year-old daughter out of her in-person learning program after Thanksgiving, in hopes of seeing her mom and stepdad over Christmas. They plan to quarantine for several weeks and get groceries delivered so they won’t be exposed to others before the trip. But whether Toledo goes through with it is still up in the air, and may change based on COVID case rates in their area.

“We’re taking things week by week, or really day by day,” said Toledo. “There is not a plan to see my mom; there is a hope to see my mom.”

And for young adults without families of their own, seeing parents at the holidays feels like a needed mood booster after a difficult year. Rebecca, a 27-year-old who lives in Washington, D.C., drove up with a roommate to New York City to see her parents and grandfather for Hanukkah. (Rebecca asked KHN not to publish her last name because she feared that publicity could negatively affect her job, which is in public health.)

“I’m doing fine, but I think having something to look forward to is really useful. I didn’t want to cancel my trip completely,” said Rebecca. “I’m the only child and grandchild who doesn’t have children. I can control my actions and exposures more than anyone else can.”

She and her two roommates quarantined for two weeks before the drive and also got tested for COVID-19 twice during that time. Now that Rebecca is in New York, she’s also quarantining alone for 10 days and getting tested again before she sees her family.

“I think, based on what I’ve done, it does feel safe,” said Rebecca. “I know the safest thing to do is not to see them, so I do feel a little bit nervous about that.”

But the best-laid plan can still go awry. Tests can return false-negative results and relatives may overlook possible exposure or not buy into the seriousness of the situation. To better understand the potential consequences of the risk you’re taking, Ropeik advises coming up with “personal, visceral” thoughts of the worst thing that could happen.

“Envision Grandma getting sick and dying” or “Grandma in bed and in the hospital and not being able to visit her,” said Ropeik. That will balance the positive emotional pull of the holidays and help you to make a more grounded decision.

Harm Reduction?

All of those interviewed for this story acknowledged that many of the precautions they’re taking are possible only because they enjoy certain privileges, including the ability to work from home, isolate or get groceries delivered — options that may not be available to many, including essential workers and those with low incomes.

Still, Americans are bound to travel over the December holidays. And much like teaching safe-sex practices in schools rather than an abstinence-only approach, it’s important to give out risk mitigation strategies so that “if you’re going to do it, you think about how to do it safely,” said Dr. Iahn Gonsenhauser, chief quality and patient safety officer at the Ohio State University Wexner Medical Center.

First, Gonsenhauser advises that you look at the COVID case numbers in your area, consider whether you are traveling from a higher-risk community to a lower-risk community, and talk to family members about the risks. Also, check whether the state you’re traveling to has quarantine or testing requirements you need to adhere to when you arrive.

Also, make sure you quarantine before your trip — recommendations range from seven to 14 days.

Another thing to remember, Gonsenhauser said, is that a negative COVID test before traveling is not a free pass, and it works only if done in combination with the quarantine period.

Consider your mode of transportation as well — driving is safer than flying.

Finally, once you’ve arrived at your destination, prepare for what might be the most difficult part: to continue physical distancing, wearing masks and washing your hands. “It’s easy to let our guard down during the holidays, but you need to stay vigilant,” said Gonsenhauser.

Victoria Knight is a Kaiser Health News reporter

vknight@kff.org, @victoriaregisk

Llewellyn King: The traitorous tribe that kills fellow Americans

President Trump touring a Honeywell mask factory (!) in May 2020. As at many other crowded events he has attended during the pandemic, Trump and his entourage, (fearful of his rebuke) refused to wear masks at this highly publicized visit.

WEST WARWICK, R.I.

When a nation goes to war its first step to survival is to protect the homeland against invasion. Every citizen is co-opted: It is their national duty.

We are on a war footing against COVID-19. It has invaded our homeland, and it is slaughtering us. Nearly 300,000 are dead and the vast hospital network in the United States is overwhelmed.

A dark cloud passes before our sun. Christmas promises more sorrow as we wait for reinforcements -- in this case, the vaccine -- to arrive.

The first line of defense against this common enemy, this indiscriminate killer, is a simple piece of layered cloth or paper held over the nose and mouth by cloth or elastic strings. It is a face mask, the simplest of defensive weapons.

But there is in the United States a tribe that has lost its head, reminiscent of Nicholas Monserrat’s great novel of 1956, The Tribe That Lost Its head. (See an old cover below.)

There are among us those who won’t defend their homeland, won’t wear masks, and accompany that treason by propagating a theory that to wear a mask is to grant a malign government total authority over the individual, and to bring about totalitarianism; or that to wear a mask is to cede manhood or endanger our way of life.

Worse, there are those who believe that it is a political statement of solidarity with the outgoing administration, with the embattled president, and the raucous nationalism that is the core of his appeal.

Some won’t wear masks out of youthful chutzpah, believing this is a disease of the old and that the young and the healthy are immune. This is a fiction they have been fed by those who should know better and most likely do know better, most of whom reside under Republican roofs, presided over by that Niagara Falls of disinformation, President Trump.

While the nation is taking fatal casualties which it doesn’t need to take, while first responders and medical personal are thrown again and again into the breach, exhausted and scared, the Trump Republicans can’t bring themselves to join the battle.

While the signs of war — a war with a terrible count in deaths -- rages on, congressional Republicans are foraging for scandals like pigs after truffles. Most of them still won’t condemn Trump for his super-spreader activities, like his rallies, parties and reckless behavior in public, which signal masks aren’t needed.

The trouble is that leaders of this headless tribe, this unacceptable face of what was the Grand Old Party, are so cowed that they won’t check the president.

The Republican Party used to be made up of muscular individuals, lawmakers who took their mandate seriously, not today’s pusillanimous followers. Incredibly, most Republican members of Congress can’t bring themselves to admit that Joe Biden won the election and will be the next president. Had there been “massive voter fraud” this wouldn’t be so. The courts would have spoken other than as they have.

All of this has played into the anti-mask movement and its lethal consequences. The virus doesn’t ask party affiliation: It is an equal-opportunity slayer.

Then there is Trump’s great enabler in the Senate, Majority Leader Mitch McConnell.

Even as millions of Americans don’t know where the next meal will come from this Christmas besides a food bank, and rent and utility bills are unpaid, McConnell, and McConnell alone, will decide who gets relief, who gets the shaft for Christmas. He can just refuse to bring a bill to the floor and end it right there. His personal concerns are paramount, not those of the other members of Congress.

Not only does McConnell not wish to understand the gravity of the situation in the country, but he also seems to relish his ability to exacerbate it, to turn his job into a Lego game for his own amusement.

This will be a bleak Christmas lit by the hope that the vaccine will deliver us from despair and bottomless hurt.

But for the vaccine to vanquish the virus, we must get our shots. If the same idiocy that shuns masks prevails, the war won’t fully be won for years when it could be ended next year.

The sight of victory is the best Christmas present, and it is possible next year if we close ranks. Those who will bear the guilt are known. They are in Washington now.

Llewellyn King is executive producer and host of White House Chronicle, on PBS. His email is llewellynking1@gmail.com and he’s based in Rhode Island and Washington, D.C.

Web Site: whchronicle.com

John O. Harney: Update on college news in New England

At Wheaton College, which has done very well in facing COVID-19. Left to right: Emerson Hall, Larcom Hall, Park Hall, Mary Lyon Hall, Knapton Hall and Cole Chapel.

BOSTON

From The New England Journal of Higher Education, a service of The New England Board of Higher Education (nebhe.org)

Faculty diversity. In the early 1990s, NEBHE, the Southern Regional Education Board (SREB) and the Western Interstate Commission for Higher Education (WICHE) collaborated to develop the first Compact for Faculty Diversity. Formally launched in 1994, with support from the Ford Foundation and Pew Charitable Trust, the compact focused on five key strategies: motivating states and universities to increase financial support for minorities in doctoral programs; increasing institutional support packages to include multiyear fellowships, along with research and teaching assistantships to promote integration into academic departments and doctoral completion; incentivizing academic departments to create supportive environments for minority students through mentorship; sponsoring an annual institute to build support networks and promote teaching ability; and building collaborations for student recruitment to graduate study. With reduced foundation support, collaboration among the three participating regional education compacts declined, but some core compact activities continued through SREB.

Now, NEBHE and its sister regional compacts are launching a collaborative, nine-month planning process to reinvigorate and expand a national Compact for Faculty Diversity. Under the proposed new compact, NEBHE, the Midwestern Higher Education Compact (MHEC), SREB and WICHE would collaborate to invest in the achievement of diversity, equity and inclusion in faculty and staff at postsecondary institutions in all 50 states. Ansley Abraham, the founding director of the SREB State Doctoral Scholars Program at the SREB, has been instrumental in the design and execution of that initiative. He recently published this short piece in Inside Higher Ed.

Fighting COVID. As the head of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) warned of the roughest winter in U.S. public-health history, Wheaton College has stood out. Our Wheaton, in Norton, Mass. (not to be confused with the Wheaton College in Illinois) developed a plan based on science that has kept positive cases low on campus and allowed in-person classes during the fall semester. Wheaton was able to limit the college’s overall fall semester case count to 23 (a .06 positivity rate among 35,000 tests) due to strong protocols, rigorous testing through the Cambridge, Mass.-based Broad Institute and a shared commitment from the community, especially students. In early November, as cases were spiking across the U.S., the private liberal arts college had its own spike of 13 positive cases in one day. But thanks to immediate contact tracing in partnership with the Massachusetts Community Tracing Collaborative, only one positive case resulted after that day, notes President Dennis Hanno. Part of Wheaton’s success owes to its twice-a-week testing throughout the semester. The college also credits its work with the for-profit In-House Physicians to complement internal staff in managing on-campus testing and quarantine/isolation housing.

New England in D.C. The COVID-19 crisis should make national health positions crucial. Earlier this week, President-elect Joe Biden tapped Dr. Rochelle Walensky, an infectious disease physician at Medical School and Massachusetts General Hospital, to lead the CDC and Dr. Vivek Murthy, who attended Harvard and Yale and did his residency at Brigham and Women’s Hospital, to be surgeon general. They’ll work with Dr. Anthony Fauci, the chief medical advisor and College of the Holy Cross graduate who has served six presidents.

Last month, as Biden’s transition team began drawing on the nation’s colleges and universities to prepare to take the reins of government, we flashed back to a 2009 NEJHE piece when Barack Obama was stocking his first administration. “As they form their White House brain trusts, new presidents tend to mine two places for talent: their home states and New England—especially New England’s universities, and especially Harvard,” we noted at the time. Most recently, two New England Congresswomen have scored big promotions on Capitol Hill. Rosa DeLauro (D.-Conn.) became Appropriations chair and Katherine Clark (D.-Mass.) was elected assistant speaker of the House. Richard Neal (D.-Mass.) was already chairman of the powerful House Ways and Means Committee.

Indebted. U.S. Sen. Elizabeth Warren (D.-Mass.), long a champion of canceling student debt, called on Biden to take executive action to cancel student loan debt. “All on his own, President-elect Biden will have the ability to administratively cancel billions of dollars in student loan debt using the authority that Congress has already given to the secretary of education,” she told a Senate Banking Committee hearing. “This is the single most effective economic stimulus that is available through executive action.” About 43 million Americans have a combined total of $1.5 trillion in federal student loan debt. Such debt has been shown to discourage big purchases, growth of new businesses and rates of home ownership among other life milestones. Warren has outlined a plan in which Biden can cancel up to $50,000 in federal student loan debt for borrowers.

Jobless recovery? Everyone knew the public health crisis would be accompanied by an economic crisis. This week, Moody’s Investors Service projected that the 2021 outlook for the U.S. higher-education sector remains negative, as the coronavirus pandemic continues to threaten enrollment and revenue streams. The sector’s operating revenue will decline by 5 percent to 10 percent over the next year, Moody’s projected. The pace of economic recovery remains uncertain, and some universities have issued or refinanced debt to bolster liquidity. (As this biting piece notes, “Just as decreased state funding has caused students to go into debt to cover tuition and fees, universities have taken on debt to keep their doors open.”)

The name of the game for many higher education institutions (HEIs) is coronavirus relief money from the federal government. NEBHE has written letters to Congress calling for increased relief based on the many New England students and families struggling with reduced incomes or job loss and the costs associated with resuming classes that were significantly higher than anticipated. These costs have been growing based on regular virus testing, contact tracing, health monitoring, quarantining, building reconfigurations, expanded health services, intensified cleaning and the ongoing transition to virtual learning. Citing data from the National Student Clearinghouse, NEBHE estimated that New England’s institutions in all sectors lost tuition and fee revenue of $413 million. And that’s counting only revenue from tuition and fees. Most institutions also face additional budget shortfalls due to lost auxiliary revenues (namely, from room and board) and the high costs of compliance with new health regulations and the administration of COVID-19 tests to students, faculty and staff. (When the relief money is spent and by whom is important too. Tom Brady’s sports performance company snagged a Paycheck Protection Program loan of $960,855 in April.) Anna Brown, an economist at Emsi, told our friends at the Boston Business Journal that higher-ed staffers working in dorms, maintenance roles, housing and food services have been hit hard, and faculty will not be far behind

Admissions blast from the past. I’ve overheard too many conversations lately with reference to “testing” and wondered if the subject was COVID testing or interminable academic exams. Given admissions tests being de-emphasized by colleges, we were reminded me of a 10-year-old piece by Tufts University officials on how novel admissions questions would move applicants to flaunt their creativity. The authors told of how “Admissions officers use Kaleidoscope, as well as the other traditional elements of the application, to rate each applicant on one or more of four scales: wise thinking, analytical thinking, practical thinking and creative thinking.” Could be their moment?

Anti-wokism. The U.S. Department of Education held “What is to be Done? Confronting a Culture of Censorship on Campus” on Dec. 8 (presumably not deliberately on the anniversary of John Lennon’s assassination). The hook was to unveil the department’s “Free Speech Hotline” to take complaints of campus violations. The event organizers contended that “Due to strong demand, the event capacity has been increased!” The department’s Assistant Secretary for Postsecondary Education Robert King began noting that we’ll hear from “victims of cancel culture’s pernicious compact” where generally “administrators cave to the mob and punish the culprit.” He noted, “Coming just behind this are Communist-style re-education camps” and assured the audience that the department has launched several investigations into these kinds of offenses like those that land awkwardly in my inbox from Campus Reform. Universities are no place for “wokism,” one speaker warned, adding that calls for diversity and tolerance actually aim to squelch unpopular opinions.

Welcome dreamers. Last week, a federal judge ordered the Trump administration to restore the Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals (DACA) program to how it was before the administration announced plans to end it in September 2017. DACA provides protection against deportation and work authorization to certain undocumented immigrants who were brought to the U.S. as children. DACA participants include many current and former college students. NEBHE issued a statement in support of DACA in September 2017 and has advocated for the initiative’s support.

John O. Harney is executive editor of The New England Journal of Higher Education.

David Warsh: A great victory in vaccine making and marketing

U.S. Government Accountability Office diagram comparing a traditional vaccine-development timeline to an expedited one

SOMERVILLE, Mass.

I often struggle to explain why I consider the Financial Times the best newspaper that I read. But my conviction begins with the consideration that the FT shows for my time and attention, as if it expects I have other things to do (in my case also reading The New York Times, The Washington Post and The Wall Street Journal). There are no “jumps,” all stories in the daily report end on the page where they begin. The front page displays just two stories (along with many teases of stories elsewhere in the paper); then come three pages of general news from around the world, followed by several pages of company and markets news; two pages of market data set in small type; a page of arts criticism, a full-page story (“The Big Read”); an editorial and letters page with four columns opposite, and, of course, the second most widely read page of the section, the “Lex” column of edgy newsy tidbits on the back. It is a thrifty package.

My deeper admiration, however, has to do to with the news values that the paper displays throughout. Last week presented a prime example. It takes a good deal of self-confidence to run out a story under the headline, “Trump vaccine chief proves critics wrong on Warp Speed: Industry veteran navigated political hurdles to boost drug companies’ fight against virus.”

But reporters Hannah Kuchler and Kiran Stacey had delivered a persuasive story. Since the article itself remains behind the FT paywall, I quote more extensively than I might otherwise to convey the gist. They began:

Sitting in the shadow of the brutalist health department building in Washington, with only a leather jacket for protection against an autumnal breeze, Moncef Slaoui cuts a defiant figure. Six months after the former GlaxoSmithKline executive left the private sector to become President Donald Trump’s coronavirus vaccine tsar, Mr Slaoui feels his decision has been vindicated, and critics of the ability of Operation Warp Speed to develop a vaccine in record time have been proved wrong.

“The easy answer for experts was to say it was impossible and find reasons why the operation would never work,” he told the Financial Times. But the vaccine push is now hailed as the bright spot in the Trump administration’s Covid-19 response, as products from Pfizer and BioNTech, Moderna, and AstraZeneca and Oxford university move closer to approval.

The next day, Karen Weintraub, of USA Today, produced an in-depth profile of Slaoui, a Moroccan-born Belgian-American vaccine developer and retired drug company executive. It is fascinating reading. But the authority of the FT account derived from the three experts the reporters quoted zeroing in on the management tool that Slaoui used to achieve his results, known as advance market commitments. or AMCs (and from a little Reuters sidebar that listed some of the spending on pre-approved doses by the U.S. government’s Biomedical Advanced Research and Development Authority (BARDA):

The central achievement of Operation Warp Speed had been accelerating investment in manufacturing, said Angela Rasmussen, a virologist at the Columbia University School of Public Health. “Normally, that would be a huge investment for a vaccine manufacturer to make, and potentially be a huge loss for them if they developed a vaccine that never went on to the market,” she said.

Even Pfizer, which did not take direct investment from Operation Warp Speed, benefited from having a $2bn pre-order for when its vaccine gets approved, said Peter Bach, director of the Center for Health Policy and Outcomes at Memorial Sloan Kettering. “Even if J&J or someone else beat them to the punch, they were going to get paid,” he said.

Stéphane Bancel, chief executive of Moderna, the lossmaking biotech which took about $2.5bn in government funding from different bodies, said the money was “very helpful”, covering the costs of trials and helping it to buy raw materials. “The entire planet is going to benefit from it,” he told the FT. “We are going to file [for approval] in the UK based on the US data paid for by the US government. We’re going to file in Europe and hopefully have a vaccine available in France and Spain and Italy, all paid for by the US government.”

Part of the charm of the story turns on its rarity; it hadn’t been easy for mainstream media to find nice things to say about the Trump administration. The road to Slaoui’s hiring probably leads back to Vice President Mike’s Pence’s appointment in February as head of the White House Coronavirus Task Force. As former governor of Indiana, Pence’s connections with the pharmaceutical industry are tight; Indianapolis is home to major firms, including Eli Lilly and Purdue Pharma. Much remains to be learned.

But the mechanism known as advanced market commitment is of comparatively recent origin. It is the discovery, if that is the word, of University of Chicago economist Michael Kremer, in a series of papers he wrote while teaching at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology and Harvard University some 20 years ago, culminating in the publication, in 2004, of Strong Medicine: Creating Incentives for Pharmaceutical Research on Neglected Diseases, with his wife, Rachel Glennerster, in 2004.

The new mechanisms they advocated were similar to those that in the 18th Century gave rise to the development of the naval chronometer, necessary to determining longitude at sea. Governmental “pull” methods could complement the inherently risky “push” of private research and development. AMCs – legally binding commitments to buy specified quantities of as yet unavailable vaccines at specified prices – were the most promising of the lot for bringing into existence medicines that otherwise might not pay. I wrote in 2004 that the general line of argument of the book was “one more example of why, more than ever, governments today need talented and sophisticated regulators. Technology policy has become as important as monetary policy – in some respects, maybe more so.” (I am told that governmentally guaranteed long-term purchase contracts were the backbone of creating the Indonesia-Japan LNG trade, and developing so-called private power generation in the U.S.)

I asked Kremer last week if he had been involved in the Warp Speed journey, The answer was no. He and co-authors had spoken to staff at the Council of Economic Advisers in the run-up to the creation of Operation Warp Speed. They had co-authored an op-ed article in The New York Times last May. But they had not met with Slaoui. He seems to have imbibed the basic idea as long ago as 2013, when he organized a session on the industry’s stock of common knowledge for the Aspen Ideas festival

Kremer was recognized with a Nobel Prize in economics, with two others, in 2018, for work on policy evaluation, including the work on vaccines. But I was struck when Wall Street Journal editorial-page columnist Daniel Henninger suggested last week that the scientists at the pharmaceutical companies who developed vaccines against COVID-19 were “the obvious recipient for 2021’s Nobel Peace Prize.”

There’s no doubt that we owe a considerable debt of gratitude to the scientists. But it was the administration’s Operation Warp Speed that organized their successful quests. A Peace Prize for the swift development of vaccines is a very good idea, not for President Trump or for Vice President Pence, nor even, to make a needed point, for Moncef Slaoui. It is a pretty thought, but remember that Russian and Chinese scientists also produced vaccines. Let the Norwegian parliament figure it out!

David Warsh, an economic historian and a veteran columnist, is proprietor of Somerville-based economicprincipals.com, where this column first appeared.

Chris Powell: Running empty trains won't increase production; some people seem to be enjoying their pandemic lockdowns

— Photo by Chianti

MANCHESTER, Conn.

While Connecticut Gov. Ned Lamont remarked the other day that state government doesn't have enough money to rescue every business suffering from COVID-19 pandemic, most people think that the federal government has infinite money and can and should make everyone whole.

Sharing that view, Connecticut U.S. Sen. Richard Blumenthal this week went to the railroad station in West Haven to join Catherine Rinaldi, president of the Metropolitan Transit Authority, in calling for an emergency $12 billion federal appropriation for the MTA, which runs the Metro-North commuter railroad line from New Haven to New York City. Metro-North has lost 80 percent of its passengers and fares because of business curtailments and the shift to working from home.

There are two problems with the appeal from Blumenthal and Rinaldi.

First, there is no need to keep Metro-North operating on a normal schedule when most passengers are missing. Except for railroad employees, no one is served by running empty trains.

Indeed, curtailment of commuter-rail service might make time to renovate the tracks and other facilities. Rather than furloughing railroad employees, hundreds of them might be reassigned temporarily to collect the trash that litters the tracks between New Haven and New York. The savings on electric power from running fewer trains still would be huge.

The second problem is that the federal government's power of money creation is infinite only technically. While nothing in law forbids the federal government from spending any amount, money is no good by itself. It has value only insofar as it has purchasing power -- only insofar as there are things to be purchased, only insofar as there is production and with so many people out of work or working less during the epidemic, production has fallen measurably. Operating empty trains won't increase production, but spending $12 billion to operate them may worsen the devaluation of the dollar, whose international value recently has fallen substantially amid so much money creation.

So it might be far better to add that $12 billion to public-health purposes.

The $12 billion desired by the MTA is only a tiny part of the largess imagined by the incoming national administration and many members of Congress who will be returning to Washington next month. They are contemplating another trillion dollars in bailouts, and that's just for starters. Such is the damage done to the national economy by the epidemic and government's often clumsy responses to it.

“Scene in club lounge,’’ by Thomas Rowlandson (1757-1827)

Amid all the seemingly free money, some people are starting to enjoy lockdowns or at least finding them tolerable, especially those who, like many government employees, get paid as usual whether they work or not.

This week two Hartford City Council members, Wildaliz Bermudez and Josh Mitchtom, called on the governor to use the state's $3 billion emergency reserve to pay everybody to stay home for a month and to stop most commercial operations in the name of slowing the spread of the virus. Bermudez and Mitchtom seemed unaware that the emergency reserve is already expected to be consumed by the huge deficits pending in next year's state budget. The reserve won't come close to covering all the shortfalls.

But then getting paid for doing or accomplishing nothing is a way of life in Hartford, encouraged by state government's steady subsidy of so many failures in the city.

Last week a group of 35 doctors went almost as far as those Hartford council members, urging the governor to close gyms and restaurants and to prohibit all “unnecessary” gatherings so as to stop the virus and prevent medical personnel from being overwhelmed. It didn't seem to bother the doctors that those businesses and their employees already have been overwhelmed by commerce-curtailment orders, suffering enormous losses, including business capital and life savings. The doctors are inconvenienced now and may be more so but they won't be losing their life savings and livelihoods.

The governor is trying to strike a balance among all these interests. Every day presents him with another difficult judgment call that upsets someone. He may be realizing that Connecticut is just going to have to tough it out and accept some casualties all around.

Chris Powell is a columnist for the Journal Inquirer, in Manchester.

Llewellyn King: COVID-19 points way to faster medicines

In a Food and Drug Administration lab in Silver Spring, Md.

WEST WARWICK, R.I.

This is the month when the national spirit should start to lift: COVID-19 vaccines could be administered by mid-December. While we won’t reach the summit of a mighty mountain this month, nor well into next year, the ascent will have begun.

It is unlikely to be a smooth journey. There will be contention, accusation, litigation and frustration. Nothing so big as setting out to administer two-dose vaccines to the whole country could be otherwise.

But the pall that hangs so heavily over us with rising deaths, exhausted first responders and overstretched hospitals, will begin to lift very slightly.

For the rest of foreseeable history, there will be accusations leveled at the Trump administration for its handling of the pandemic — or its failure to handle it.

But one thing is certain: Our faith in our ability to make superhuman scientific efforts in the face of crisis will be restored. Developing a COVID-19 vaccine will be compared to putting a man on the Moon.

The large pharmaceutical companies, known collectively as Big Pharma, have shown their muscle. The lesson: Throw enough research and unlimited money at a problem, accelerate the regulatory process, and a solution can result.

Even globalization gets a good grade.

The first-to-market vaccine comes from American pharmaceutical giant Pfizer. But the vaccine was developed at its small German subsidiary, BioNTech, by a husband-and-wife team of first-generation Turkish immigrants. (Beware of whom you exclude.)

Biopharmaceutical research often takes place this way, akin to how it happens in Silicon Valley: Small companies innovate and invent, and larger ones gobble them up and provide the all-important resources for absurdly complicated and expensive clinical trials. These contribute mightily to the cost of new drugs. A new “compound” -- as a drug is called in the trade -- can cost up to $2 billion to bring to market; and financial reserves are needed, should there be costly lawsuits.

The development of new drugs looks like an inverted pyramid. Linda Marban, a researcher and CEO of Capricor Therapeutics Inc., a clinical-stage biotechnology company based in Los Angeles, explained it to me: “The last 20 years have shown a seismic change in how drugs and therapies are developed. Due to the speed at which science is advancing, and the difficulty of early-stage development, most of the early-stage work is done by small companies or the occasional academic. Big Pharma has moved into the role of late-stage clinical, sometimes Phase 2, but mostly Phase 3 and commercial development.”

In the upheaval occasioned by the pandemic, overhaul of the Food and Drug Administration looms large as a national priority. It must be able -- maybe with a greater use of artificial intelligence and data management -- to assess the safety and efficiency of desperately needed drugs without the current painful and often fatal delays.

Marban said of the FDA clinical-trials process: “It is the most laborious and frustrating process which delays important scientific and medical discoveries from patients. There are many situations where patients are desperate for therapy, but we have to climb the long and ridiculous ladder of doing clinical trials due to inefficiencies at the site which include nearly endless layers of contracting, budget negotiations, IRB [Institutional Review Board] approvals and, finally, interest and attention from overworked clinical trial staff.”

This situation, according to Marban, is compounded by the FDA’s requirement for clinical trials conducted and presented in a certain way, which often precludes getting an effective therapy to market. “If we simplify this process alone, we could move rapidly towards treatments and even cures for many horrific diseases,” she added.

War is a time of upheaval, and we are at war against the COVID-19. But war also involves innovation. We have proved that speed is possible when bureaucracy is energized and streamlined.

When COVID-19 is finally vanquished, it should leave a legacy of better medical research and sped-up approval procedures, benefiting all going forward.

Llewellyn King is executive producer and host of White House Chronicle, on PBS. His email is llewellynking1@gmail.com and he’s based in Rhode Island and Washington, D.C.

Linda Gasparello

Co-host and Producer

"White House Chronicle" on PBS

Mobile: (202) 441-2703

Websi

Janie Grice: For an essential workers' bill of rights

From OtherWords.org

During the pandemic, essential workers have become public heroes. These frontline workers include tens of millions of retail employees, from those who stock our grocery shelves to those filling orders for Amazon.

With so many people seeing firsthand how low-wage workers make our society function, we have a once-in-a-lifetime opportunity to transform our society so that everyone can earn quality pay and benefits.

But beyond symbolic displays of gratitude, essential retail workers have not yet seen this transformation.

At Walmart, the largest private employer in the country, workers are still not receiving adequate hazard pay, safety protections or paid leave. The company remains the top employer of workers who are forced to rely on food stamps and other aid.

At Amazon, employees still face rigid limits on bathroom breaks and other policies that compromise their health and safety in the midst of a pandemic. At least 20,000 Amazon employees have tested positive for COVID-19.

These issues are deeply personal to me.

For four years, I worked at my local Walmart as a cashier and later as a customer-service manager — all while raising my son as a single mother and working on a bachelor’s degree. I started out making only $7.78 an hour and was never able to get a full-time position, let alone a stable schedule.

I understand the stresses faced by retail workers at our country’s largest employers, including struggling to pay bills and not being able to care for a sick child because of unpredictable hours and low wages.

Despite the challenges of the job, I got my degree in social work and now support retail workers across the country as an organizer for United for Respect. This national organization of working people fights for bold policies that would improve lives, particularly those in the retail industry.

One of our priority goals is an Essential Workers Bill of Rights, which would guarantee improved health and safety protections, universal health care, increased pay and paid leave, and whistleblower protection.

Workers also need a real voice in policy matters that affect our lives, from union organizing rights to personal protective equipment. So we’re pushing to get worker representation on corporate boards.

Without these rights, corporate executives and politicians will continue to put their interests before those of essential workers and their families. And retail workers, especially Black women like me, will continue to live in poverty while working for some of the largest and wealthiest employers in the world.

During the pandemic, the wealth of Amazon CEO Jeff Bezos and Walmart’s Walton family has skyrocketed to record levels, according to a new report by Bargaining for the Common Good, the Institute for Policy Studies, and United for Respect. The contrast between this wealth and the struggles essential workers face is shameful.

If this nation wants a real conversation about dignity for people like me and the people I organize, then we have to embrace bold solutions. And we can start with an Essential Workers Bill of Rights and a voice for workers in decision making.

Think about what corporate America would look like if workers actually had a seat at the table. Corporations would prioritize investments in their workers instead of padding their CEOs’ pockets. The millions of retail workers who now have to rely on food stamps and other public assistance could provide for their families.

Let’s push toward this dream by expanding opportunities for the working people who are critical to the health and security of our nation — today, during the pandemic, and beyond.

Janie Grice is an organizer with United for Respect, based in Marion, S.C.

— Photo by Lars Frantzen

Ed Cervone: How a Maine college has adjusted to pandemic and recession

From The New England Journal of Higher Education, a service of The New England Board of Higher Education (nebhe.org)

In October 2019, NEBHE called together a group of economists and higher education leaders for a meeting at the Federal Reserve Bank of Boston to discuss the future of higher education (Preparing for Another Recession?). No one suspected that just months later, a global pandemic would turn the world upside down. Today, the same challenges highlighted at the meeting persist. The pandemic has only amplified the situation and accelerated the timeline. It also has forced the hands of institutions to advance some of the changes that will sustain higher education institutions through this crisis and beyond.

At the October 2019 meeting, the panelists identified the primary challenges facing colleges and universities: a declining pool of traditional-aged students, mounting student debt, increasing student-loan-default rates and growing income inequality.

Taken together, these trends were creating a perfect storm, simultaneously putting a college education out of reach for more and more students and forcing some New England higher-education institutions to close or merge with other institutions. Those trends were expected to continue.

Just three months later, COVID-19 had begun spreading across the U.S., and the education system had to shut down in-person learning. Students returned home to finish the semester. Higher-education institutions were forced to go fully remote in a matter of weeks. Institutions struggled to deliver content and keep students engaged. Inequities across the system were accentuated, as many students faced connectivity obstacles. Households felt the economic crunch as the unemployment rate increased sharply.

By summer, the pandemic was in full swing. Higher-education institutions looked to the fall. They had to convince students and their families that it would be safe to return to campus in an uncertain and potentially dangerous environment. Safety measures introduced new budgetary challenges: physical infrastructure upgrades, PPE and the development of screening and testing regimens.

In the fall, students resumed their education through combinations of remote and in-person instruction. Activities and engagement looked very different due to health and safety protocols. Many institutions experienced a larger than usual summer melt due to concerns from students and families about COVID and the college experience.

Despite these added challenges, New England higher-education institutions have adapted to keep students engaged in their education, but are running on small margins and expending unbudgeted funds to continue operations during the public-health crisis. Recruiting the next class of students is proving to be a challenge. The shrinking pool of recruits will contract even more and reaching them is much more difficult. Many low- and moderate-income families will find accessing higher education even harder and may choose to defer postsecondary learning.

Change is difficult but a crisis can provide necessary motivation. Maine institutions are using this opportunity to make the changes needed to address the current crisis that will also set them on a more sustainable path over the long term. Maine has a competitive advantage relative to the nation. A low-density rural setting and the comprehensive public-health response from Gov. Janet Mills have kept the overall incidence rate down. Public and private higher-education institutions coordinated their response, developed a set of protocols for resuming in-person education that were reviewed by the governor and public health officials, and successfully returned to in-person education in the fall.

In addition, Mills established the Economic Recovery Committee in May and charged the panel with identifying actions and investments that would be necessary to get the Maine economy back on track. This public process has reinforced the critical ties between education and a healthy economy. Not only is higher education a focus of the work, but the governor appointed Thomas College President Laurie Lachance to co-chair the effort. In addition, the governor appointed University of New England (in Biddeford, Maine) President James Herbert, University of Maine at Augusta President Rebecca Wyke, and Southern Maine Community College President Joseph Cassidy to serve on the committee.

At the individual institution level, a wide array of innovations will enable Thomas College to endure the pandemic and position itself for the future. Consider:

Affordability. Most Thomas College students come from low- to medium-income households and are the first in their families to attend college, so-called “first-generation” students. Cost will always be top of mind. For motivated students, Thomas has an accelerated pathway that allows students to earn their bachelor’s degree in three years (sometimes two) and they have the option of doing a plus-one to earn their master’s. This, coupled with generous merit scholarship packages (up to $72,000 of scholarship over four years) and a significant transition to Open Educational Resources to reduce book costs, represents real savings and the opportunity to be earning sooner than their peers.

Student success supports. Accelerated programs (or any program, for that matter) are not viable without purposeful strategies to keep students on track to complete based on their plans. In addition to a traditional array of academic and financial supports, Thomas College has invested in a true wraparound offering serving the whole student. For eligible students, Thomas has a dedicated TRIO Student Support Services program. Funded through a U.S. Department of Education grant, the program provides academic and personal support to students who are first-generation, are from families of modest incomes, or who have an identified disability. The benefits include individualized academic coaching, financial literacy development and college planning support for families. Thomas was also first in the nation to have a College Success program through JMG (Maine’s Jobs for America’s Graduates affiliate). Thomas College has expanded physical- and mental- health services in the wake of the pandemic, including our innovative Get Out And Live program, which uses Maine’s vast natural setting to provide a range of exciting four-season, outdoor activities for the whole campus community.

Employability. Thomas College students see preparing for a rewarding career as part of their college experience. This is core to the college’s mission and more important than ever in an uncertain economic environment. It is so important that it is guaranteed through the college’s Guaranteed Job Program. Thomas College’s Centers of Innovation focus on the employability of each student. Students pursue a core academic experience in their chosen field, and staff work with each student starting in their first semester to increase their professional and career development. This means field experiences and internships with Maine’s top employers. About 75 percent of Thomas College students have an internship before graduation. As part of their college experience, Thomas College students are coached to earn professional certificates, licenses and digital badges prior to graduation that make them stand out in their professional fields and improve their earning potential. These might include certificates in specific sectors like accounting and real estate or digital badges that show proficiency in professional skills like Design Thinking or Project Management, to name just a few. On the academic side, Thomas has expanded both undergraduate and graduate degree offerings to programs where the market has great demand, including Cybersecurity, Business Analytics, Applied Math, Project Management and Digital Media. Delivery is flexible in terms of mode and timing. And the institution is now offering Certificates of Advance Study (15-credit programs) in Cybersecurity, Human Resource Management and Project Management to meet the stated needs of our business partners seeking to upskill their employees.

Looking Ahead

Some of these changes and investments align with challenges identified before the pandemic as necessary if higher education institutions are to survive and sustain changing demographic and economic trends. The pandemic provided the opportunity to focus on these more quickly, allowing institutions such as Thomas College to right the ship today and set the right course for tomorrow.

Ed Cervone is vice president of innovative partnerships and the executive director of the Center for Innovation in Education at Thomas College, in Waterville, Maine., also the home of Colby College.

David Warsh: The mysterious machinery of epidemic models

“The Plague of Athens ‘‘ by Michiel Sweerts (painted in 1652-54), illustrating the devastating epidemic that struck Athens in 430 B.C., as described by the historian Thucydides.

SOMERVILLE, Mass.

It is not difficult to identify a 9/11 moment in the 2020 COVID-19 pandemic, an event after which everything changed. Until mid-March, politicians in Britain and the United States were cautiously optimistic. Prime Minister Boris Johnson advised, “We should all basically just go about our normal daily lives.” President Trump, in an Oval Office address on March 11, said that for the vast majority of Americans, the risk is very, very low.”

Five days later, on March 16, the British government took the first of a series of measures leading to a lockdown on March 23. On March 17, President Trump read a statement to a press briefing:

My administration is recommending that all Americans, including the young and healthy, work to engage in schooling from home when possible. Avoid gathering in groups of more than 10 people. Avoid discretionary travel. And avoid eating and drinking at bars, restaurants and public food courts. If everyone makes this change or these critical changes and sacrifices now, we will rally together as one nation and we will defeat the virus. And we’re going to have a big celebration all together. With several weeks of focused action, we can turn the corner and turn it quickly.

What happened? Imperial College, London, released a model-based study on March 16 that made headlines around the world, predicting as many as 2.2 million deaths might occur in the U.S., and 510,000 in the U.K. as a result of the pandemic. To this point, 265,000 US deaths have been reported, and another 58,030 in Britain.

Since March, economists have gone to work seeking to better understand the machinery of epidemiological models and the theories on which they are based. In “An Economist’s Guide to Epidemiology Models of Infectious Disease,” in the Journal of Economic Perspectives, Fall 2020, Christopher Avery, William Bossert, Adam Clark, Glenn Ellison and Sarah Fisher Ellison lay out the facts above, along with some of their findings.

Epidemiology has become more empirical over time, they say, and epidemiologists are learning to add parameters to their models. But they make less of a distinction between theory and empirical approaches than do economists. Meanwhile, “a model which posits a symmetric, bell-shaped evolution of cases over time cannot accommodate repeated changes in the rate of spread due to changing regulations, changing public perception, and ‘quarantine fatigue.’”

Not surprisingly, economists have begun looking for means of suppressing the virus by changing behaviors in manners as cost-effective as possible. Representative is James Stock, of Harvard University, who argued in September that lockdowns are too are too blunt a method to rely on in most cases. In “Policies for a Second Wave,” for a special summer edition of Brookings Papers on Economic Activity, Stock and David Baqaee, Emmanuel Farhi and Michael Mina proposed framing the wearing of masks as a patriotic duty, pursuing cheap and rapid testing, stressing contact tracing and quarantine, and implementing waste-water testing as a means of surveillance once the virus is suppressed.

Epidemiology is not the only discipline to come under economists’ lens. Bruce Sacerdote, Ranjan Schgal and Molly Cook ask Why Is All Covid-19 News Bad News? in a National Bureau of Economic Research working paper out this month. They fault mainstream media for underplaying news of vaccine trials and school re-openings. Ninety-one percent of articles by U.S. major media outlets have been negative in tone since the first of the year compared with 54 percent abroad and 65 percent in scientific journals. Stories discussing Donald Trump and hydroxychloroquine were more numerous than all stories combined about companies and individuals working on a vaccine, they complained.

Of course those stories about hydroxychloroquine may have been more about the nature of the president’s leadership than about COVID-19. Even so, there is indeed evidence of hierarchy and momentum in the reporting: what Wall Street Journal columnist Holman Jenkins, Jr. goes on about. It’s going to be a long time before the strange coincidence of Donald Trump and the virus is untangled. Integrated assessment of the pandemic has far to go.

David Warsh, a veteran columnist and an economic historian, is proprietor of economicprincipals.com, where this piece first ran.

Rachana Pradhan: How big pharma money colors Operation Warp Speed

April 16 was a big day for Moderna, the Cambridge, Mass., Massachusetts biotech company on the verge of becoming a front-runner in the U.S. government’s race for a coronavirus vaccine. It had received roughly half a billion dollars in federal funding to develop a COVID shot that might be used on millions of Americans.

Thirteen days after the massive infusion of federal cash — which triggered a jump in the company’s stock price — Moncef Slaoui, a Moderna board member and longtime drug-industry executive, was awarded options to buy 18,270 shares in the company, according to Securities and Exchange Commission filings. The award added to 137,168 options he’d accumulated since 2018, the filings show.

It wouldn’t be long before President Trump announced Slaoui as the top scientific adviser for the government’s $12 billion Operation Warp Speed program to rush COVID vaccines to market. In his Rose Garden speech on May 15, Trump lauded Slaoui as “one of the most respected men in the world” on vaccines.

The Trump administration relied on an unusual maneuver that allowed executives to keep investments in drug companies that would benefit from the government’s pandemic efforts: They were brought on as contractors, doing an end run around federal conflict-of-interest regulations in place for employees. That has led to huge potential payouts — some already realized, according to a KHN analysis of SEC filings and other government documents.