Glass nips better

A collector's cabinet full of miniature bottles

— Photo by kerinin

Adapted from Robert Whitcomb’s “Digital Diary,’’ in GoLocal24.com

Rhode Island state legislators are considering banning those plastic nip liquor bottles of which you see all too many along roads, sidewalks and on beaches.

Good idea. They’ve added to the plastic pollution you see everywhere and that’s bad for wildlife as well as aesthetics (and thus tourism). That’s in part because all too many of the people who buy them are slobs and/or drunk.

And the smallness of the nip bottles discourages reuse.

If only more people demanded glass containers, which can be used indefinitely. And even if slobs dropped them in the water or on, say, a beach, they gradually wear down from the abrasion from sand, etc., and can become quite beautiful Anyone remember collecting “sea glass” (aks “beach glass”) as a kid?

Will someone some day finally invent a plastic that degrades rapidly with no harm to the environment?

“Sea glass’’

Judith Graham: New COVID rules for visitors distress relatives of elderly people in nursing homes

As COVID-19 cases rise again in nursing homes, at least for now, a few states have begun requiring visitors to present proof that they’re not infected before entering facilities, stoking frustration and dismay among family members.

Navigating Aging focuses on medical issues and advice associated with aging and end-of-life care, helping America’s 45 million seniors and their families navigate the health-care system.

Officials in California, New York, and Rhode Island say new COVID testing requirements are necessary to protect residents — an enormously vulnerable population — from exposure to the highly contagious omicron variant. But many family members say they can’t secure tests amid enormous demand and scarce supplies, leaving them unable to see loved ones. And being shut out of facilities feels unbearable, like a nightmare recurring without end.

Severe staff shortages are complicating the effort to ensure safety while keeping facilities open; these shortages also jeopardize care at long-term care facilities — a concern of many family members.

Andrea DuBrow’s 75-year-old mother, who has severe Alzheimer’s disease, has lived for almost four years in a nursing home in Danville, Calif. When DuBrow wasn’t able to see her for months earlier in the pandemic, she said, her mother forgot who she was.

“This latest restriction is essentially another lockdown,” DuBrow said at a meeting last week about California’s new regulations. “The time that my mom has left when she can recognize in some small locked-away part of her that it is me, her daughter, cleaning her, feeding her, holding her hand, singing her favorite songs — that time is being stolen from us.”

“This is a huge inconvenience, but what’s most upsetting is that no one seems to have any kind of long-term plan for families and residents,” said Ozzie Rohm, whose 94-year-old father lives in a San Francisco nursing home.

Why are family members subject to testing requirements that aren’t applied to staffers, Rohm wondered. If family members are vaccinated and boosted, wear good masks, stay in a resident’s room, and practice rigorous hand hygiene, do they pose more of a risk than staffers who follow these procedures?

California was the first state to announce new policies for visitors to nursing homes and other long-term care facilities on Dec. 31. Those took effect on Jan. 7 and remain in place for at least 30 days. To see a resident, a person must show evidence of a negative covid rapid test taken within 24 hours or a PCR test taken within 48 hours. Also, covid vaccinations are required.

In a statement announcing the new policy, the California Department of Public Health cited “the greater transmissibility” of the omicron variant and the need to “protect the particularly vulnerable populations in long-term care settings.” Throughout the pandemic, nursing home residents have suffered disproportionately high rates of illness and death.

New York followed California with a Jan. 7 announcement that nursing home visitors would need to show proof of a negative rapid test taken no more than a day before. And on Jan. 10, Rhode Island announced a new rule requiring proof of vaccination or a negative covid test.

Patient advocates are worried other states might adopt similar measures. “We are concerned that omicron will be used as an excuse to shut down visitation again,” said Sam Brooks, program and policy manager for the National Consumer Voice for Quality Long-Term Care, an advocacy group for people living in these facilities.

“We do not want to go back to the past two years of lockdowns in nursing homes and resident isolation and neglect,” he continued.

That’s also a priority for the federal Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services, which has emphasized since Nov. 12 residents’ right to receive visitors without restriction as long as safety protocols are followed. Nursing homes could encourage but not require visitors to take tests in advance or provide proof of covid vaccination, guidance from CMS explained. Safety protocols included wearing masks, rigorous hand hygiene, and maintaining adequate physical distance from other residents.

With the rise of omicron, however, facilities pushed back. On Dec. 17, an organization representing nursing home medical directors and two national long-term care associations sent a letter to CMS’ administrator asking for more flexibility to “protect resident safety” and “place temporary visitation restrictions in nursing homes.” On Jan. 6, CMS affirmed residents’ right to visitation but said states could “take additional measures to make visitation safer.”

Asked for comment about the states’ recent actions, the federal agency said in a statement to KHN that “a state may require nursing homes to test visitors as long as the facility provides the rapid antigen tests, and there are enough testing supplies. … However, if there are not enough rapid testing supplies, the visits must be allowed to occur without a test (while still adhering to other practices, such as masking and physical distancing).”

Some relief from test shortages may be at hand under the Biden administration’s new plan to distribute four free tests per household. But for family members who visit nursing home residents several times a week, that supply won’t go very far.

Since the start of the year, tension over the balance between safety and residents’ rights to visitation has intensified. In the week ended Jan. 9, 57,243 nursing home staffers reported covid infections, almost 10 times as many as three weeks before. During the same period, resident infections rose to 32,061, almost eight times as many as three weeks earlier.

But outbreaks are occurring against a different backdrop today. More than 87 percent of nursing-home residents have been fully vaccinated, according to CMS, and 63 percent have also received boosters, reducing the risk that covid poses. Also, nursing homes have gained experience handling outbreaks. And the toll of nursing home lockdowns — loneliness, despair, neglect, and physical deterioration — is now far better understood.

“We have all seen the negative effects of restricting visitation on residents’ health and well-being,” said Joseph Gaugler, a professor who studies long-term care at the University of Minnesota’s School of Public Health. “For nursing homes to go back into a bunker mentality and shut everything down, that’s not a solution.”

Amid egregious staffing shortages, “we need people in these buildings who can take care of residents, and often those are visitors who are basically functioning as unpaid certified nursing assistants: grooming and toileting residents, turning and repositioning them, feeding them, stretching, and exercising them,” said Tony Chicotel, a staff attorney at California Advocates for Nursing Home Reform.

Nearly 420,000 staffers have left nursing homes since February 2020, according to the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics, worsening existing shortages.

When DuBrow learned of California’s new testing requirement for visitors, she arranged to get a PCR test at a testing site on Jan. 6, expecting results within 48 hours. Instead, she waited 104 hours before getting a response. (Her test was negative.) Eager to visit her mother, DuBrow called every CVS, Walgreens, and Target in a 25-mile radius of her home asking for a test but came up empty.

In a statement, the California Department of Public Health said the state had established 6,288 covid testing sites and sent millions of at-home tests to counties and local jurisdictions.

In New York, Democratic Gov. Kathy Hochul has pledged to deliver nearly 1 million COVID tests to nursing homes, where visitors can take them on the spot, but that presents its own problems. “We don’t want to test visitors who are lining up at the door. We don’t have the clinical staff to do that, and we need to focus all our staff on the care of residents,” said Stephen Hanse, president and CEO of the New York State Health Facilities Association, an industry organization.

With current staff shortages, trying to ensure that visitors are wearing masks, physical distancing, and adhering to infection control practices is “taxing on the staff,” said Janine Finck-Boyle, vice president of regulatory affairs at Leading Age, which represents not-for-profit long-term care providers.

“Really, the challenges are enormous,” said Gaugler, of the University of Minnesota, “and I wish there were easy answers.”

Judith Graham is a Kaiser Health News reporter.

Cynthia Hammond: Does Conn.-R.I. Amtrak bypass plan still live?

Amtrak Acela train near Old Saybrook, Conn.

From ecoRI News (ecori.org)

CHARLESTOWN, R.I.

A U.S. Department of Transportation “Providence to New Haven Capacity Planning Study” has some local officials wondering whether the original plan to run train tracks through sections of their town, and other Rhode Island and Connecticut towns, might not be dead after all.

The study is part of the Northeast Corridor 2035 Plan, or “C35,” a 15-year plan to guide investment in rail service in the Northeast.

The C35 describes the plan, which has an estimated cost of $130 billion, as the first phase of the long-term vision for the corridor described in the Federal Railroad Administration’s 2017 NEC Future plan, which includes “making significant improvements to NEC rail service for both existing and new riders, on both commuter rail systems and Amtrak.”

In 2016, Charlestown officials learned, by chance, that the Federal Railroad Administration (FRA) had released its Tier 1 environmental impact statement (EIS) on a plan to straighten train tracks in the Northeast to accommodate high-speed rail service. The plan wasn’t met with broad enthusiasm.

The FRA had sent letters to affected towns and the Narragansett Indian Tribe in 2015, soliciting comments on the draft EIS, but according to a blog post on the plan by the Charlestown Citizens Alliance political action committee, there was no specific mention of new tracks going through Charlestown or other neighboring towns.

"Most of these governments have no recollection of receiving communication from the FRA,” the post read. “The letter does not say that new rails and a new rail route are proposed in your community. When no comments came from one of the most impacted towns, this should have suggested to the FRA that the local community and local stakeholders were not aware and engaged in the review process.”

The unpleasant surprise included in the plan was the Old Saybrook to Kenyon Bypass, which would have moved rail traffic directly through Old Saybrook, Conn., Westerly and Charlestown, bisecting neighborhoods, nature preserves and historic farms. The towns and Narragansett Indian Tribal officials fought the plan, and the Record of Decision, released in 2017, omitted the bypass.

But the omission didn’t mean that the bypass had simply gone away, and the Charlestown Citizens Alliance warned that the decision left the door open to a study which could resurrect the bypass.

The alliance’s blog post published after the decision reads: “The July 12, 2017 ROD calls for a study that could possibly bring back the Bypass. We will remain vigilant throughout this study process to work to stop the Bypass from being resurrected.”

In an effort to learn more about the FRA’s intentions, Town Council President Deborah Carney spoke last August with Amtrak’s chief executive officer, William J. Flynn, who said the most likely route for a New Haven to Providence high-speed rail track would be along the Interstate 95 corridor.

Carney, who said she had been put in contact with Flynn by a mutual acquaintance in Charlestown, acknowledged that while there is no guarantee that plans for the original bypass that would have bisected the town would not be revived, she felt reassured that the I-95 route would be preferred.

“They’re doing the feasibility study and analysis, so there’s no concrete plan at all, but [Flynn] said if they were to go forward with something, it would most likely either to parallel Route 95, like the northern part of the state, or it would involve improving the existing line that goes along the southern coast - where it is now.”

Rhode Island Department of Transportation (DOT) director Peter Alviti represents the state on the 18-member FRA Northeast Corridor Commission (NECC), which is studying rail demand and capacity in the Northeast New Haven to Providence rail corridor.

Alviti, and DOT intermodal programs chief Stephen Devine, met in November with Charlestown officials, Rhode Island state Rep. Blake Filippi, R-New Shoreham, and state Sen. Elaine Morgan, R-Hopkinton.

Alviti told the group the NECC would require a study of future ridership demand on the New Haven to Providence route before any decision was made. (DOT did not support the originally proposed Old Saybrook to Kenyon bypass.)

DOT spokesperson Charles St. Martin said in a recent emailed statement that his agency was counting on more public consultation this time around.

“Yes, RIDOT met recently with Charlestown officials regarding this proposal,” he said. “We told them we are aware that Amtrak is retaining a consultant to do an initial market study only to first determine the demand for higher speed services. This effort will be starting soon and will include a robust public participation component.”

St. Martin also noted, “Rhode Island’s position remains the same as in 2017, when the state indicated opposition of the bypass route in Charlestown.”

What still vexes some Charlestown officials, however, is the continued lack of any FRA response to the town’s inquiries.

In August 2021, at the request of the Town Council, town administrator Mark Stankiewicz wrote a letter to FRA interim administrator Amit Bose, asking for more information regarding the New Haven to Providence study.

After receiving no response to the first letter, Stankiewicz sent a second letter on Dec. 10, which read, in part, “Given the limited available information and the absence of any communication from the FRA, we are in a quandary as to how to ensure Charlestown receives timely information and is able to relay our input and concerns about the New Haven to Providence Capacity Planning Study.”

Charlestown Planning Commission chair Ruth Platner, who was not mollified by Flynn’s statements, said she had not expected the FRA to respond.

“I’m not surprised that they’re not answering, but I think it’s important that the town is asking,” she said. “The thing is, they took the [Old Saybrook to Kenyon] bypass out of the decision, but they didn’t replace it with anything, and the whole rail plan is based on the assumption that there’s going to be huge job growth in the big cities — in Washington, Philadelphia New York and Boston, but that’s not Rhode Island and that’s not Connecticut. The high-speed rail is to connect those big cities, and they want to do it, one way or another.”

Platner said she believed that pandemic-related changes which have made it possible for many Americans to move out of large cities and work from home will impact the study.

“I think what’s happened now, because of the pandemic, there’s kind of a wait and see, to see what this means for growth. Are the cities not going to grow?” she said.

Another factor to consider, Platner said, is the proximity of the I-95 corridor to the coast, and therefore, its vulnerability to rising sea levels.

“It’s a beautiful ride, and it’s right along the coast, and the water is right there. The tracks are going to be under water, so they have to do something, and the problem has to be solved, and it’s going to be solved with some sort of realignment away from the coast,” she said.

Carney said her concerns had been largely put to rest after her conversation with Flynn and the meeting with Alviti.

“In our conversations with Peter Alviti, and also William Flynn, it doesn’t seem as though that Old Saybrook to Kenyon is going to be revived, but I understand where people are coming from,” she said. “You know, if it’s their property that’s impacted, obviously they’re concerned about it, but I will say that Director Alviti kind of put our minds at ease, you know, in saying ‘This is not in the 10-year plan.’”

Platner, however, warned the affected towns to remain vigilant.

“The town of Charlestown needs to be involved, so that we can protect the people and the environment here,” she said. “What we don’t want is to have a plan be created that we don’t know about.”

The FRA did not respond to several requests for comment.

Cynthia Hammond is an ecoRI News contributor

Todd McLeish: Seeking strategies for sustaining bay scallops

Bay scallop staring at you with its blue eyes

From ecoRI News (ecori.org)

In the Great Salt Pond on Block Island, native bay scallops are thriving like nowhere else in Rhode Island. Scientists from The Nature Conservancy survey the 673-acre tidal harbor every autumn and have recorded hundreds of scallops each year, despite as many as 50 recreational shellfishermen harvesting scallops from the pond each November and December.

The same cannot be said of the rest of the Ocean State’s waters, however, where bay scallops are few and far between.

On Block Island, Diandra Verbeyst leads a three-person team of Nature Conservancy scuba divers and snorkelers who monitor 12 sites around the Great Salt Pond. They have counted an average of 225 scallops annually since 2016, up from just 44 observed by previous observers in 2007, the first year of monitoring.

“There are slight rises and falls from year to year, but the population is pretty stable,” Verbeyst said. “Based on the 12 sites we monitor, the population is indicating that there is spawning happening each year, and there is recruitment to the population.”

In addition to scallop data, Verbeyst and her team also collect information on water quality and other environmental conditions during their surveys.

“The scallops are an indication that the ecosystem is healthy and doing well, and for me, that’s fascinating in itself,” she said. “No matter where you are in the pond, there’s a good chance you’ll see a scallop.”

Bay scallops are bivalve mollusks with 30-40 bright blue eyes that live in shallow bays and estuaries up and down the East Coast, preferring habitats where eelgrass is abundant. They are short-lived animals — most don’t live more than two years — and are significantly smaller than sea scallops, which are found farther offshore and are harvested by the millions by New Bedford-based fishermen.

Chris Littlefield, a Nature Conservancy coastal projects director and former part-time shellfisherman on Block Island, recalled collecting scallops as a child in the Great Salt Pond 50 years ago, and he has been gathering them in small numbers for his family’s consumption ever since. He said the scallop population received a boost in 2010, when immature scallops grown at the Milford {Conn.} Laboratory of the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration were dispersed into the pond in a project funded by the Natural Resources Conservation Service.

“That project broke through some kind of threshold,” Littlefield said. “Scallops weren’t as abundant before that, and they used to be confined to certain key locations and that was it. But now they’re more abundant and more people are finding them and harvesting them.”

Unlike Nantucket, Martha’s Vineyard and a few locations on Cape Cod and Long Island, where regular seeding of immature bay scallops has resulted in thriving commercial fisheries, Rhode Island has a tiny commercial fishery for bay scallops — fewer than three fishermen participate — and the fishery is not sustainable.

Anna Gerber-Williams, principal marine biologist for the Rhode Island Department of Environmental Management’s Division of Marine Fisheries, just completed the first year of a three-year effort to assess the state’s bay scallop population. She is focused primarily on the salt ponds in South County, especially Point Judith Pond and Ninigret Pond, which historically had healthy bay scallop populations.

“We manage and regulate the bay scallop harvest, but besides Block Island, we haven’t had an actual assessment of what the population looks like in Rhode Island,” Gerber-Williams said. “We know it’s pretty low, and we know the actual commercial harvest numbers are very low. But we don’t have anything to base our management on. The hope is that this project can turn into more long-term monitoring, similar to what’s done on Block Island, and maybe lead to restoration efforts.”

Based on her first year of surveys, Gerber-Williams said there are self-sustaining populations of bay scallops in Point Judith Pond, and their abundance can fluctuate significantly from year to year.

“Scallops are very habitat-dependent,” she said. “The habitat in the salt ponds is very patchy, and those patches are very small.”

Unlike clams, which bury themselves in the sand, bay scallops sit on the seafloor and can swim around by rapidly opening and closing their shell, making them difficult to track and count. Gerber-Williams said they are threatened by several varieties of crabs, which can easily crush the scallops’ shells with their claws.

“Part of the scallop’s strategy is to hide from the crabs in the eelgrass,” she said. “When they’re younger, they attach themselves to eelgrass blades to keep themselves above the bottom and out of reach of predators.”

Dan Torre at Aquidneck Island Oyster Co. experimented this year with growing bay scallops in cages in the Sakonnet River off Portsmouth. He bought scallop seed from area hatcheries last July, and they are approaching marketable size now. He has contracted with one local restaurant to buy his experimental crop, with hopes of scaling up the operation next year.

“I believe there’s a market, but it’s a niche market,” he said. “Normally with sea scallops, you sell just the shelled adductor muscle, but with bay scallops you sell the whole animal. The shelf life isn’t the longest, but it seems like there are a bunch of restaurants that are eager to try them.”

In an effort to figure out how best to restore wild bay scallop populations in the region, the Rhode Island Commercial Fisheries Research Foundation is collaborating with The Nature Conservancy to synthesize what is known about the history of the bay scallop population and fishery in Point Judith Pond.

According to Dave Bethoney, the foundation’s executive director, it will be combined with information about scallop fisheries in Massachusetts and Long Island, N.Y., as a first step to developing a restoration plan.

“How to make them sustainable is the real puzzle,” Bethoney said. “Even successful efforts on Long Island are based on a seeding plan — getting scallops every year from aquaculture facilities to replenish them. They have successful populations, but they’re not self-sustaining. I don’t know how we change that.”

Gerber-Williams agreed.

“In my opinion, the way to boost populations here and keep them at a level that’s sustainable for a good fishery in Rhode Island, we would have to have a seeding program similar to what they have in Long Island and Martha’s Vineyard,” she said. “Every year they put out thousands of baby bay scallops. They seed their salt ponds every single year to keep a decent fishery going.

“So the next step for us would be to do that kind of seeding program in Rhode Island. We’re in the process of creating a restoration plan for various species of shellfish in Rhode Island, and my hope is that bay scallops are a part of that.”

Hopefully the current researchers go back to the North Cape shellfish injury restoration project, which included release of bay scallop seed into the South County salt ponds, to learn about what worked or did not work for the multi-year that wrapped up by 2010. The reports are available and some of us who worked on the project are available to discuss challenges and successes.

Todd McLeish is an ecoRI News contributor.

Eelgrass is prime habitat for bay scallops.

Llewellyn King: Climate crisis, population growth and a solution; N.E.'s densest community

WEST WARWICK, R.I.

It wasn’t front and center at the recent climate-change summit, COP26, in Glasgow, but it was whispered about informally, in the corridors and over meals.

For politicians, it is flammable, for some religions, it is heresy. Yet it begs a hearing: the growth of global population.

While the world struggles to decarbonize, saving it from catastrophic sea-level rise and the other disasters associated with climate change, there is no recognition officially anywhere that population plays a critical part.

People do things that cause climate change from burning coal to raising beef cattle. A lot of people equal a lot of pollution equals a big climate impact, obvious and incontrovertible.

In 1950, the global population was at just over 2.5 billion. This year, it is calculated at 7.9 billion. Roughly by mid-century, it is expected to increase by another 2 billion.

There is a ticking bomb, and it is us.

There was one big, failed attempt to restrict population growth: China’s one-child policy. Besides being draconian, it didn’t work well and has been abandoned.

China is awash with young men seeking nonexistent brides. While the program was in force from 1980 to 2015, girls were aborted and boys were saved. The result: a massive gender imbalance. One doubts that any country will ever, however authoritarian its rule, try that again.

There is a long history to population alarm, going back to the 18th century and Thomas Malthus, an English demographer and economist who gave birth to what is known as Malthusian theory. This states that food production won’t be able to keep up with the growth in human population, resulting in famine and war; and the only way forward is to restrict population growth.

Malthus’s theory was very wrong in the 18th Century. But it had unfortunate effects, which included a tolerance of famine in populations of European empire countries, such as India. It also played a role in the Irish Great Famine of 1845-53, when some in England thought that this famine, caused by a potato blight, was the fulfillment of Malthusian theory, and inhibited efforts to help the starving Irish. Shame on England.

The Boston Irish Famine Memorial is on a plaza between Washington Street and School Street. The park contains two groups of statues to contrast an Irish family suffering during the Great Famine of 1845–1852 with a prosperous family that had emigrated to America. Southern New England was a focal point for Irish immigrants to America, and Irish-Americans still comprise the largest ethnic group in much of the region.

The idea of population outgrowing resources was reawakened in 1972 with a controversial report titled “Limits to Growth” from the Club of Rome, a global think tank.

This report led into battles over the supply of oil when the energy crisis broke the next year. The anti-growth, population-limiting side found itself in a bitter fight with the technologists who believed that technology would save the day. It did. More energy came to market, new oil resources were discovered worldwide, including in the previously mostly unexplored Southern Hemisphere.

Since that limits-to-growth debate, the world population has increased inexorably. Now, if growth is the problem, the problem needs to be examined more urgently. I think that 2022 is the year that examination will begin.

Clearly, no country will wish to go down the failed Chinese one-child policy, and anyway, only authoritarian governments could contemplate it. Free people in democratic countries don’t handle dictates well: Take, for example, the difficulty of enforcing mask-wearing in the time of the Covid pandemic in the United States, Germany, Britain, France and elsewhere.

If we are going to talk of a leveling off world population we have to look elsewhere, away from dictates to other subtler pressures.

There is a solution, and the challenge to the world is whether we can get there fast enough.

That solution is prosperity. When people move into the middle class, they tend to have fewer children. So much so that the non-new-immigrant populations are in decline in the United States, Japan and in much of Europe -- including in nominally Roman Catholic France and Italy. The data are skewed by immigration in all those countries -- except Japan, where it is particularly stark. It shows that population stability can happen without dictatorial social engineering.

In the United States, the not-so-secret weapon may be no more than the excessive cost of college.

Llewellyn King is executive producer and host of White House Chronicle, on PBS. His email is llewellynking1@gmail.com and he’s based in Rhode Island and Washington, D.C.

Web site: whchronicle.com

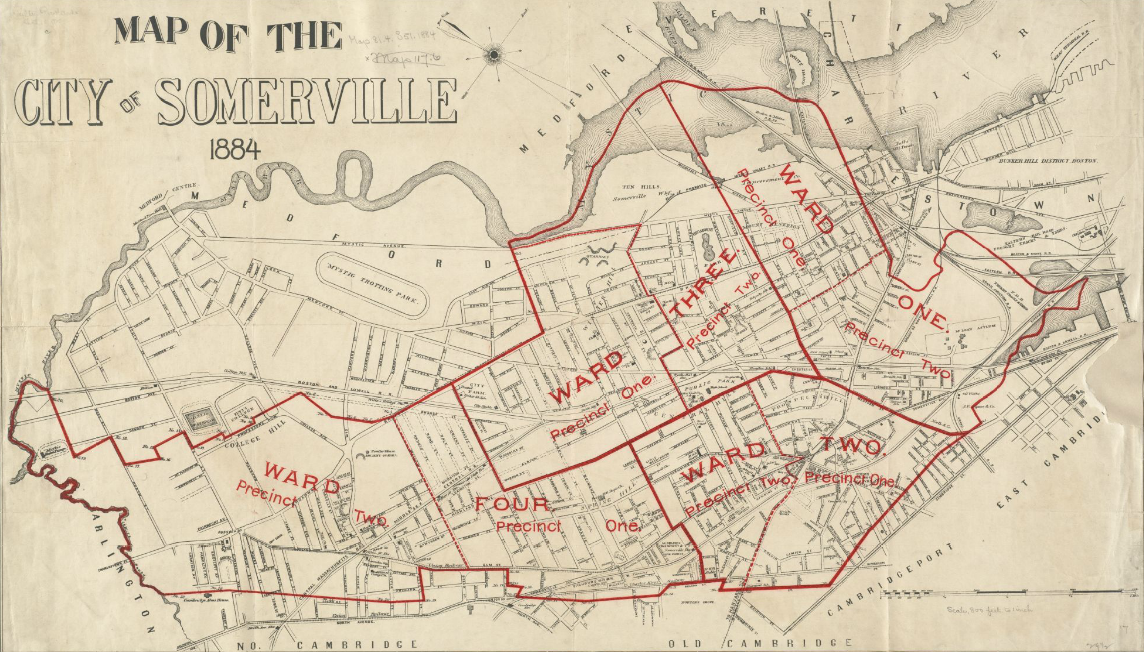

Occupying slightly over 4 square miles, with a population of 81,360 (as of the 2019 Census) (including a myriad of immigrants from all over the world), Somerville is the most densely populated community in New England and one of the most ethnically diverse cities in the nation.

Todd McLeish: Small rodents play important roles in maintaining woodland ecosystems in N.E.

Female White-Footed mouse on sumac bush.

— Photo by Peterwchen

From ecoRI News (ecori.org)

When University of Rhode Island teaching professor Christian Floyd brought students in his mammalogy class to a nearby forest in September to set 50 box traps to capture mice and other small mammals, he was surprised the next morning when more than half of the traps contained a live white-footed mouse.

“I usually expect to catch three or four, and on a good year we’ll get about 12, but you never get 50 percent trap success,” URI’s rodent expert said. “White-Footed Mouse populations fluctuate in boom and bust years, and this year seems to be a boom year.”

Floyd speculated that abundant acorns, recent mild winters and healthy growth of concealing vegetation were probably factors in the unusual numbers of mice captured this year. But whatever the reason for their abundance, healthy mouse populations are a good sign for local forests.

A new study by scientists at the University of New Hampshire concluded that small mammals such as mice, voles, shrews and chipmunks play a vital role in keeping forests healthy by eating and dispersing the spores of mushrooms, truffles, and other fungi to new areas.

According to Ryan Stephens, the post-doctoral researcher at UNH who led the study, all trees form a mutually beneficial relationship with fungi. Healthy forests are dependent on hundreds of thousands of miles of fungal threads called hyphae that gather water and nutrients and supply it to the trees’ roots. In return, the trees provide the fungi with sugars they produce in their leaves. Without this symbiotic relationship, called mycorrhizae, forests would cease to exist as we know them.

Different fungal species enhance plant growth and fitness during different seasons and under different environmental conditions, so maintaining diverse fungal communities is vital for forest composition and drought resistance, according to Stephens.

But fungal diversity declines when trees die because of insect infestations, fires and timber harvests. That is why the role of small mammals in dispersing mushroom spores is so critical to forest ecology.

To effectively support healthy forests, Stephens said these animals must scatter spores of the right kind of fungi in sufficient quantities and to appropriate locations where tree seedlings are growing. But not every kind of small mammal disperses all kinds of spores, so it’s imperative that forest managers support a diversity of mammal species in forest ecosystems.

“By using management strategies that retain downed woody material and existing patches of vegetation, which are important habitat for small mammals, forest managers can help maintain small mammals as important dispersers of mycorrhizal fungi following timber harvesting” and other disturbances, Stephens said. “Ultimately, such practices may help maintain healthy regenerating forests.”

Distributing mushroom spores isn’t the only important role played by mice and voles in the forest environment. They are also tree planters.

“Almost all rodents cache food — they have a cache of acorns, seeds, maybe truffles, little bits of mushrooms,” Floyd said. “Our oak forests are probably all planted by rodents. They scurry around and dig holes and bury things.”

White-Footed Mice, which Floyd said are the most abundant mammal in Rhode Island, are also voracious consumers of the pupae of gypsy moths.

“For a mouse, gypsy moth pupae are like little jelly donuts; they’re a delicacy,” he said. “The theory is that when mouse numbers are high, they can regulate gypsy moth populations.”

Mice, voles, shrews and chipmunks are also the primary prey of most of the carnivores in the forest, from hawks and owls to foxes, weasels, fishers, and coyotes. These small mammals are a vital link in the food chain between the plant matter they eat and the larger animals that eat them.

Are these small mammals the most important players in maintaining healthy forests? Probably not. Floyd believes that accolade probably goes to the numerous invertebrates in the soil. But this new research on the dispersal of mushroom spores by mice and voles may move them up a notch in importance.

Todd McLeish is an ecoRI News contributor.

Michelle Andrews: In pandemic, many employers have expanded mental-health coverage

In group therapy

As the COVID-19 pandemic burns through its second year, the path forward for American workers remains unsettled, with many continuing to work from home while policies for maintaining a safe workplace evolve. In its 2021 Employer Health Benefits Survey, released Nov. 20, KFF found that many employers have ramped up mental health and other benefits to provide support for their workers during uncertain times.

See Rhode Island organization’s role below.

Meanwhile, the proportion of employers offering health insurance to their workers remained steady, and increases for health-insurance premiums and out-of-pocket health expenses were moderate, in line with the rise in pay. Deductibles were largely unchanged from the previous two years.

“With the pandemic, I’m not sure that employers wanted to make big changes in their plans, because so many other things were disrupted,” said Gary Claxton, a senior vice president at KFF and director of the Health Care Marketplace Project. (KHN is an editorially independent program of the foundation.)

Reaching out to a dispersed workforce is also a challenge, with on-site activities like employee benefits fairs curtailed or eliminated.

“It’s hard to even communicate changes right now,” Claxton said.

Many employers reported that since the pandemic started they’ve made changes to their mental-health and substance-use benefits. Nearly 1,700 nonfederal public and private companies completed the full survey.

At companies with at least 50 workers, 39% have made such changes, including:

31% that increased the ways employees can tap into mental-health services, such as telemedicine.

16% that offered employee assistance programs or other new resources for mental health.

6% that expanded access to in-network mental health providers.

4% that reduced cost sharing for such visits.

3% that increased coverage for out-of-network services.

Workers are taking advantage of the services. Thirty-eight percent of the largest companies with 1,000 or more workers reported that their workers used more mental health services in 2021 than the year before, while 12% of companies with at least 50 workers said their workers upped their use of mental health services.

Thundermist Health Center is a federally qualified health center that serves much of Rhode Island. (It’s based in Woonsocket.) The center’s health plan offers employees an HMO and a preferred provider organization, and 227 workers are enrolled.

When the pandemic hit, the health plan reduced the co-payments for behavioral health visits to zero from $30.

“We wanted to encourage people to get help who were feeling any stress or concerns,” said Cynthia Farrell, associate vice president for human resources at Thundermist.

Once the pandemic ends, if the health center adds a co-payment again, it won’t be more than $15, she said.

The pandemic also changed the way many companies handled their wellness programs. More than half of those with at least 50 workers expanded these programs during the pandemic. The most common change? Expanding online counseling services, reported by 38% of companies with 50 to 199 workers and 58% of companies with 200 or more workers. Another popular change was expanding or changing existing wellness programs to meet the needs of people who are working from home, reported by 17% of the smaller companies and 34% of the larger companies that made changes.

Beefing up telemedicine services was a popular way for employers to make services easier to access for workers, who may have been working remotely or whose clinicians, including mental-health professionals, may not have been seeing patients in person.

In 2021, 95% of employers offered at least some health care services through telemedicine, compared with 85% last year. These were often video appointments, but a growing number of companies allowed telemedicine visits by telephone or other communication modes, as well as expanded the number of services offered this way and the types of providers that can use them.

About 155 million people in the U.S. have employer-sponsored health care. The pandemic didn’t change the proportion of employers that offered coverage to their workers: It has remained mostly steady at 59% for the past decade. Size matters, however, and while 99% of companies with at least 200 workers offers health benefits, only 56% of those with fewer than 50 workers do so.

In 2021, average premiums for both family and single coverage rose 4%, to $22,221 for families and $7,739 for single coverage. Workers with family coverage contribute $5,969 toward their coverage, on average, while those with single coverage pay an average of $1,299.

The annual premium change was in line with workers’ wage growth of 5% and inflation of 1.9%. But during the past 10 years, average premium increases have substantially exceeded increases in wages and inflation.

Workers pay 17% of the premium for single coverage and 28% of that for family coverage, on average. The employer pays the rest.

Deductibles have remained steady in 2021. The average deductible for single coverage was $1,669, up 68% over the decade but not much different from the previous two years, when the deductible was $1,644 in 2020 and $1,655 in 2019.

Eighty-five percent of workers have a deductible now; 10 years ago, the figure was 74%.

Health-care spending has slowed during the pandemic, as people delay or avoid care that isn’t essential. Half of large employers with at least 200 workers reported that health-care use by workers was about what they expected in the most recent quarter. But nearly a third said that utilization has been below expectations, and 18% said it was above it, the survey found.

At Thundermist Health Center, fewer people sought out health care last year, so the self-funded health plan, which pays employee claims directly rather than using insurance for that purpose, fell below its expected spending, Farrell said.

That turned out to be good news for employees, whose contribution to their plan didn’t change.

“This year was the first year in a very long time that we didn’t have to change our rates,” Farrell said.

The survey was conducted between January and July 2021. It was published in the journal Health Affairs and KFF also released additional details in its full report.

Michelle Andrews is a Kaiser Health News reporter.

Woonsocket's city hall

—Photo by Kenneth C. Zirkel

Caitlin Faulds: How do users interpret warnings about coastal water quality?

Misquamicut Beach, in southern Rhode Island

From ecoRI News (ecori.org)

A new study on perceptions of coastal water quality shows users may have more difficulty interpreting warning signs than previously thought.

The University of Rhode Island study, recently published in the Marine Pollution Bulletin, surveyed more than 600 recreational users around Narragansett Bay regarding their understanding of water quality to find that water quality had “multiple meanings.” A complicated conceptualization of water quality could have big implications for water policy and management.

“Water quality is pretty complex for people,” said Tracey Dalton, a URI marine affairs professor and Rhode Island Sea Grant director, who co-authored the study. “It’s not as simple as the chemical components that we tend to manage for.”

Water quality managers typically look at a variety of biochemical and physical indicators, including nutrients, temperature, acidity, oxygen levels, phytoplankton, fecal coliform and enterococci, to see if a site meets surface water quality guidelines set by the Environmental Protection Agency and outlined in the Clean Water Act.

But, according to the recent study led by URI marine affairs doctoral candidate Ken Hamel, these indicators can be difficult to understand for beachgoers, who more commonly tote sunscreen and beach towels than sterile sample bottles, plankton nets or conductivity, temperature and depth (CTD) sensors.

With help from his research team, Hamel conducted hundreds of in-person surveys at 19 sites along the Rhode Island shoreline. They asked recreational users to grade water quality in the area on a scale from 1 to 10, and then explain the reasons for their score.

Users generally perceived water quality in upper Narragansett Bay to be worse than in the lower bay. This assessment aligned fairly well with biochemical reports in the area, Hamel said, generally cleaner on the southern, open end of the bay than in the more urban, post-industrial north.

“You’ve got to wonder … how do people make that judgment,” he said. “Because they don’t necessarily know how much sewage effluence is in the water. They can’t see E. coli or enterococcus. They can’t smell it. Nutrients are also invisible.”

After a statistical analysis of the responses, the survey showed nearly 23 percent of users based water quality determinations on the presence of macroalgae or seaweed.

“Seaweed, which is a perfectly ecologically healthy organism for the most part — people perceive that as a water quality problem,” Hamel said. “From a Clean Water Act perspective, [seaweed in] the north is a water quality problem, the south is not.”

In the northern reaches of Narragansett Bay, macroalgal concentrations are often the result of nutrient overload, especially nitrogen and phosphorous borne of fertilizers and road runoff. It can indicate a problem with marine water quality.

But further south, macroalgae are less associated with pollution and are not necessarily an indicator of nutrient enrichment or water degradation, according to Hamel. Seaweed grows in reefs off the coast, breaks up due to wave action and can be blown on shore, especially on south-facing sands.

With no simple association between water degradation and seaweed, Hamel was surprised to see so many people use it as a basis for water quality determinations.

“There is very little research on perceptions of algae or seaweed period,” Hamel said. “It’s just a very understudied subject.”

Shoreline trash, “broadly defined” pollution, strong odor, water clarity, swimming prohibitions and nearby sewage treatment plants were also cited by beachgoers as indicators of poor water quality.

“People figured if there was a sewage plant nearby the water must be dirty,” Hamel said. “Although if you think about it, it’s slightly backward right. That should make the water a little bit cleaner.”

Another 9 percent of respondents also indicated that firmly held place beliefs played a role in water quality grades. These place beliefs, Hamel said, were “hard to pin down,” but were based primarily on the reputation of a place, whether linked to former industry or long-embedded regional knowledge of Narragansett Bay.

“One person even said, ‘This place is too upper bay.’ Like it was just common sense for them that water in the upper bay must be bad,” Hamel said.

Narragansett Bay visitors with water-quality questions can find detailed reports for sites through the Rhode Island Department of Environmental Management and through the Narragansett Bay Commission. But, according to Hamel, the survey shows a need and opportunity to better engage beachgoers in water quality education, so the average recreation user can more accurately read the warnings presented in an environment.

“As a group of social scientists, we’re really interested in understanding how people are connected to their environment,” Dalton said. “From a policy perspective, it's really important to understand what the general public thinks since they’re the ones who are going to coastal sites, they’re the ones affected by policies.”

The Clean Water Act, Hamel said, has gaps in the way it was written and interpreted by water managers. As set out in 1972, the federal law mandated that states reduce and eliminate pollutants primarily to protect wildlife and recreation. Nicknamed the “fishable/swimmable goal,” the law gives priority to recreational users.

The law is enforced at the state level, with slight variations in procedure, though it typically takes the form of measuring and monitoring biochemical and physical variables. But, according to Hamel, that strategy can leave out certain stakeholders and minimize non-user concerns.

“There’s a lot of other people that use the water that aren’t necessarily in it or on it,” he said. “And their … perspectives aren’t really considered by the way the Clean Water Act is implemented.”

There isn’t necessarily anything wrong with the law, Hamel said, and it has been instrumental in improving water quality. But policymakers and managers could better address all stakeholders and “more explicitly consider” the needs of non-users, he said, including those who may work or live nearby.

“In terms of how we direct our investments and direct our funds, we want to make sure that we’re also addressing what people care about,” Dalton said. “It’s really important to ground that in what the understanding is of the concept of water quality.”

Caitlin Faulds is an ecoRI News journalist.

Llewellyn King: As climate warms, utilities must become much more resilient

The severe flooding in Greater New York, New Jersey and New England from the remnants of Hurricane Ida, that storm’s devastation in New Orleans and much of the rest of Louisiana and the winter freeze in Texas usher in a new reality for the electric industry, showing how outdated their infrastructure has become and how they have to much more expect the unexpected.

Resilience is the word used by the utilities to describe their ability to speedily restore power, to bounce back after an outage. This year, resilience has been put to the test with major challenges affecting electric utilities from coast to coast. Mostly, the results have been disappointing to catastrophic.

It is reasonable to believe that resilience means that if there is an outage power will be back on forthwith or within hours, and that is often the case.

But as the attacks on the system from aberrant weather have become more frequent and severe, the bounce back has been closer to struggle back slowly.

Two cases tell a tale of catastrophe. Recently, the complete loss of electricity to New Orleans during Hurricane Ida, much of which is still in the dark and with people suffering without water in their homes, along with the absence of light, air conditioning, or the ability to charge a cell phone.

Even before Ida tore into the Gulf Coast, teams from other utilities were on their way to help. ConEd in New York was one of many utilities that had trucks rolling to the scene before Ida hit. That kind of quick, fraternal response is often what is meant by resilience. Bold and well-coordinated though it may have been, it was not nearly enough. Entergy, which supplies the power to the area, failed the resilience test.

The other standout was in the failure of the Texas grid when Winter Storm Uri struck in the middle of February. It froze much of Texas for five days and more than 150 people died, some by freezing to death in their homes. The unfortunately named Electric Reliability Council of Texas (ERCOT), which operates the electric grid of Texas, abominably failed the resilience test.

Some of the natural-gas supply was cut off during the deep freeze because the system hadn’t been weatherized, but the gas that did flow also flowed money.

The gas operators made enormous profits, including Energy Transfer, which made $2.4 billion. Not only had the gas operators not signed on to the concept of resilience, but the idea of commonweal was absent.

While electric utilities -- there are a few large electric utilities and more than 80 small ones in Texas -- struggled to honor their mandate to serve, the gas suppliers, according to those in the electric utility industry, served their mandate only to their shareholders.

Rayburn, the electric cooperative that has a service area near Dallas, spent what it had budgeted for three years in just five days on gas purchases, CEO David Naylor told me.

On my PBS show, White House Chronicle, Paula Gold-Williams, president and CEO of CPS Energy, the large, municipally owned gas and electric utility in San Antonio, said she thought that the suppliers of gas to electric generators should be regulated as Texas utilities are.

Wildfires in the West, storms in the East and up the center of the country have put a huge strain on the electric utilities. What is clear is that “resilience” needs to be defined in a much broader sense. That whole infrastructure of the electric-utility industry needs to be re-examined with a view to surviving monstrous weather. The cost in lives and in treasure is very high when electricity, the essential commodity of modern life, fails.

This new imperative comes at a bad time for the electric-utility industry, which is struggling with daily cyber-attacks, converting from fossil fuels to alternatives, and straining to find new, durable storage systems.

One of the trends to greater security is to encourage microgrids – small, self-contained grids that can store and generate electricity, often from renewables like solar. These can disengage from the grid in times of stress and continue providing power to the microgrid.

Other suggestions include undergrounding electric lines. California’s Pacific Gas and Electric has proposed undergrounding 10,000 miles of lines to counter wildfires sparked by downed cables. The cost might be insupportably high -- over $1 million a mile in level ground, according to one estimate.

Entergy, according to The Energy Daily, has 2,000 miles of lines down in New Orleans. Burying just the most vulnerable lines in the nation would be a massive civil engineering undertaking at a daunting cost. Other ideas, please?

Llewellyn King is executive producer and host of White House Chronicle, on PBS. His email is llewellynking1@gmail.com, and he’s based in Rhode Island and Washington, D.C.

Long Island Expressway in New York City shut down due to flooding as the remnants of Hurricane Ida swept through the Northeast on Sept. 1-2

— Photo by Tommy Gao

Frank Carini: Plastic pollution is burying a coastline

Rhode Island beach scene

—Photo by Frank Carini

From ecoRI News (ecori.org)

Dave McLaughlin has been organizing, leading and documenting Rhode Island shoreline cleanups for the past 15 years, and he’s noticed one item, which comes in all shapes, sizes and colors, becoming increasingly prevalent: plastic.

When the Middletown-based nonprofit he leads, Clean Ocean Access, began cleaning up Aquidneck Island’s coastline in 2006, staff and volunteers found bed frames, tires, refrigerators, glass bottles, aluminum cans and lots of fishing gear.

Today, a deluge of plastic now swamps the shoreline. McLaughlin said the petroleum-based tidal wave began about a decade ago. Besides the typical debris of plastic bags, straws, Capri Sun pouches, Styrofoam cups, candy wrappers and omnipresent cigarette butts — most filters are made of cellulose acetate, a plastic — this evolving pollution now features Jewel pods and the explosion of single-use plastics and multilayered packaging.

Multilayered packaging has several thin sheets of different materials, such as aluminum, paper and plastic, that are laminated together. It’s not made for recycling.

This growing amount of plastic packaging is washing up on shorelines worldwide, including along the Ocean State’s 420 miles of coast — arguably the state’s most important economic engine. In 2015, about 45 percent of plastic waste generated globally was from packaging materials, according to a 2018 white paper. A 2017 report found up to 56 percent of plastic packing manufactured in developing countries consists of multilayered materials.

It’s been estimated that every U.S. household uses nearly 60 pounds of multilayered packaging annually. Most isn’t or can’t be recycled, and much, like other plastic-related trash, ends up in the sea or washed up along the coast.

As of 2019, Clean Ocean Access had held 1,171 cleanups and removed nearly 69 tons of marine debris — about 118 pounds per cleanup — from Aquidneck Island’s shoreline and out of its coastal waters. Of the 14 most common items collected on land, half have been predominantly plastic: straws and stirrers; 6-pack holders; food wrappers; caps and lids; bottles; bags; and toys, according to the organization’s 2006-2019 Clean Report.

Of the 13 most common items pulled from the marine waters of Portsmouth, Middletown and Newport, five are plastic heavy: bleach and cleaning bottles; fishing line; sheets and tarps; strap bands; and buoys and floats.

All of these plastic items, on land and in the water, continue to break down into smaller and smaller toxic pieces that work their way up the food chain.

July Lewis, volunteer manager for Save The Bay, has been involved with shoreline cleanups since 2007. She said the one trend that is inescapable is the growing amount of microplastics and “tiny trash” — what she called pulverized pieces of bottle caps, cups and other plastics — that litter Rhode Island’s coastline.

“We are seeing more and more of it every year,” Lewis said. “It’s become part of the ecosystem.”

Peter Panagiotis, the well-known professional surfer better known as Peter Pan, has been surfing in Rhode Island waters, mostly along the coast of Narragansett, since 1963. He told ecoRI News that plastic now litters the coastline.

“There’s more plastic pollution, especially in the winter there is garbage everywhere,” the Pawtucket resident said. “Plastic pollution is the problem. There’s a lot more plastic garbage.”

Plastic debris makes up a growing amount of the material that is picked up annually during Save The Bay coastal cleanups. In 2019, 2,807 volunteers collected 7.8 tons of trash along 94 miles of shoreline — or about 5.5 pounds per person and 166 pounds per mile.

Of the material collected that year, plastic and foam pieces less than 2.5 centimeters long accounted for 27 percent of all the rubbish collected — 42,841 pieces of tiny trash. Microplastics, pieces less than 5 millimeters long (0.5 centimeters), are harder to see and pick up, but they are a growing presence.

The repulsive 2019 haul included plenty of other plastic: candy and chip wrappers (11,136); bags (6,213); straws and stirrers (4,629); lids (1,942); and utensils (1,050).

For nearly a decade, Geoff Dennis has been a one-man cleanup crew for the Little Compton shoreline. Dennis “got a taste for trash” while walking along Goosewing Beach in 2012.

“It really bothers me. The first time I walked with the dog, I came back with over 100 Mylar balloons,” he told ecoRI News in 2017. “If I can start a conversation with people about it, that’s great. But most people just don’t care.”

Between 2012 and 2020, the longtime quahogger picked up 35,607 pieces of trash along the banks of the Sakonnet River and at Goosewing Beach Preserve and a few other places. The vast majority of it was some form of plastic, from bottles to wads for shotgun shells.

In fact, the amount of plastic he has collected just along Little Compton waters is shocking:

Balloons made from the resin polyethylene terephthalate, a clear, strong and lightweight plastic belonging to the polyester family and commonly referred to as Mylar, a registered trademark owned by Dupont Tejjin Films (2012-20): 8,510. That total doesn’t include the 1,194 latex balloons he collected in 2019 and ’20.

Plastic bottle caps (2017 and 2020): 4,107.

Plastic shotgun shells (2017 and 2020): 1,552.

Plastic wads for shotgun shells (2017 and 2020): 527.

Plastic straws (2016-19): 1,526.

Plastic snack bags (2015-2020): 867.

Plastic bags (2018-2020): 440.

Plastic and foam cups (2018-2020): 386.

Plastic coffee cup lids (2020): 94

K-Cup pods (2019 and 2020): 210.

Plastic nips (2020): 207.

Plastic lighters (2017 and 2020): 188.

Plastic bottles and aluminum cans (2012-2020): 15,324.

In some places along Rhode Island’s marine waters, such as Fields Point in Providence, plastic pollution is now part of the shoreline environment. (Save The Bay)

Lewis noted that in some places, such as Fields Point, at the head of Narragansett Bay in Providence, plastic litter is indistinguishable from the natural world. She said most of this shoreline litter is generated from eating, drinking and smoking.

Save The Bay, too, is finding plenty of plastic flotsam and jetsam bobbing in Rhode Island’s coastal waters. The Providence-based organization is playing a leading role in establishing baseline data on the amount of microplastics within the Narragansett Bay watershed. The goal is to highlight this growing problem and draw attention to regional efforts to eliminate single-use plastics, such as cups, straws and bags.

The three staffers — Michael Jarbeau, Kate McPherson and David Prescott — largely responsible for conducting Save The Bay’s trawls for plastic have been surprised by how much they have found in local waters. When they started, they expected some microplastic trawls would come up empty. They’re still waiting for that to happen.

The crew has done more than 24 surface trawls, and every one has produced plastic bits, from nurdles, the raw building blocks for plastic bottles, bags and straws, to microfibers from polyester fleeces and other synthetic clothing to microbeads, which are used in exfoliating scrubs and in some toothpastes.

All of this overused plastic is changing the composition of Rhode Island’s marine waters. These petroleum byproducts don’t biodegrade. They remain in the environment for centuries. Their long-term impacts on environmental and public health aren’t close to being fully understood. Their impact on the natural world, however, has already been well documented.

Plastic bags float in Narragansett Bay, Block Island Sound and the Ocean State’s other marine waters like jellyfish. Turtles, whales and other sea animals often mistake them for food, causing many to starve or choke to death.

Adult seabirds inadvertently feed tiny trash to their chicks, often causing them to die when their stomachs become filled with fake food. As plastic breaks down into smaller fragments — microplastics may contain toxic chemicals as part of their original plastic material or adsorbed environmental contaminants such as PCBs — fish and shellfish become increasingly vulnerable to the toxins these polluted particles collect.

At least two-thirds of the world’s fish stocks are suffering from plastic ingestion, including local seafood favorites striped bass and quahogs.

On the positive side of the Ocean State’s shoreline trash problem, both McLaughlin and Lewis said they are seeing less dumping of big items, such as tires and appliances.

clean-ups by volunteers seem futile, a new batch will soon appear. Why aren't officers of the companies that make these plastics required to clean it up or pay someone to do so?

Frank Carini is editor of ecoRI News.

Llewellyn King: Has COVID launched a new age for workers?

Most workers would like to slash the time they spend commuting.

WEST WARWICK, R.I.

Millions of Americans appear to be echoing the words of the Johnny Paycheck song “Take This Job and Shove It.” This is a sentiment that is changing the work scene, the way we work, and the future of work.

The workers of America are shuffling the deck in a way that has never happened before. It is accentuating an acute labor shortage.

I receive lists of job openings every day and the common denominator seems to be that you must show up at a place of business. Among the big and seemingly frantic employers are FedEx, Walmart and Amazon. Warehouse workers and delivery drivers are the most sought-after employees.

To overcome the labor shortage, wages are rising and adding to the rising inflation -- although what part of that rise is labor cost isn’t clear. Other factors are pandemic-induced supply chain disruptions, a tightening of food flows from California and other Western states, and the acute housing shortage. The economy is rebalancing; and so are workers, reassessing their lives and making changes.

There has been a severe shortage of skilled workers for a long time. It has been felt almost everywhere from construction to electric line workers. It is just worse now, exacerbated by immigration restrictions and workers who have joined the reshuffle.

During the COVID-19 lockdown, millions of individuals have assessed what they do and, apparently, found it wanting.

America’s workforce isn’t returning to the jobs that they held before the lockdown. Some are trying new things; others are demanding changes in the workplace. There is a demand for more remote working. The rat race is running short of willing rats.

Commuting seems to be the one big no-no. People in the major work hubs such as New York, Washington, Chicago, Boston and San Francisco have sampled the joys and the failings of working from home, and commuting has lost.

I know people who used to spend four or five hours every day getting to work and back home in all these cities. Sitting in a traffic jam is neither creative nor the best use of human life, these people are now saying.

In the movie Network, Peter Finch bellows, “I’m as mad as hell, and I’m not going to take this anymore!” That is the new sentiment towards rigid travel and rigid work schedules. Working from home has taken people up the hill and shown them the valley, and they have liked the valley.

Other workers, particularly at the lower end of the work scale, have wondered whether they wouldn’t be happier doing something else now that they have had time to ponder. A friend of mine’s daughter who was a professional waiter in Florida now works for a printer. She has found she gets a more dependable income, better hours and that incalculable: a happier work environment.

I love small business, and I believe it to be the essential force for innovation and job creation. But it is also where petty boss-tyrants flourish. Lousy, egomaniacal employers aren't hard to find, especially in the restaurant business.

When I worked as a waiter in New York, between journalism jobs, I knew waiters who dreamed of the great restaurant where the tips are generous and, above all, the “patron is nice.” Unseen, there is a lot of cussing and pressure in any restaurant, and job security is unknown.

Enforced downtime has caused many to wonder whether they are even in the right line of work; whether the money, prestige or social recognition that may have gone with their old job was worth it.

For others, the gig economy has beckoned, where the employer has been cut out. Particularly, this is true of young people in communications and related work. Geeks are a hot item and can contract directly. But others, from landscape gardeners to plumbers, are going gig. The downside is there are no benefits, from Social Security deductions to pensions and health care. Society is lagging in recognizing this new arena of work.

Peculiarly, we aren’t at full employment. Unemployment is hovering around 5.9 percent and has gone up slightly as the summer has progressed. This raises the question of how many of the formerly employed are now in the gig economy, skewing the figures.

We are in what is, in effect, a post-war recovery. Traditionally, that is a time for social readjustment, for old bonds to be loosed, and for new energy to be released. Is it time to sack the boss?

Llewellyn King is executive producer and host of White House Chronicle, on PBS. His email is llewellynking1@gmail.com and he’s based in Rhode Island and Washington, D.C.

Web site: whchronicle.com

Llewellyn King: The Internet — where lies tangle with truth

“The Internet Messenger,” by Buky Schwartz, in Holon, Israel

WEST WARWICK, R.I.

In this, the Information Age, truth was supposed to be the great product of the times. Spread at the speed of light, and majestically transparent, the world of irrefutable truth was supposed to be available at the click of a key.

The Internet was to be like “Guinness World Records,” conceived by Sir Hugh Beaver, managing director of the Guinness Brewery, when he missed a shot while bird hunting in Ireland in 1951. This resulted in an argument between him and his hosts about the fastest game bird in Europe, the golden plover (which he missed) or the red grouse. The idea for a reference book that would settle that sort of thing was born, which could help promote Guinness and settle barroom disputes.

The first edition was published as “The Guinness Book of Records” in 1955 and was an instant bestseller. You might have thought that there was a thirst for truth as well as beer.

Despite the U.S. Supreme Court’s (dominated by Republican justices) repeated rejection of any suggestion that the presidential election of 2020 was fraudulent and that it wasn’t won by Joe Biden, the Republican governor of Texas, Greg Abbott, has called a rare special session of the Texas legislature to pass a restrictive voting package that will likely include the power for the legislature to overturn any election result it deems fraudulent.

This is happening across Republican-controlled states. They are ready to fix something big that isn’t broken.

Abbott has called the special session because the Texas legislature -- thanks to the Democrats denying him quorum in a parliamentary procedure -- didn’t get what amounts to a rollback of democracy in the regular session. Second time lucky.

What these Republicans are doing is equivalent to forcing men to wear blinders so they don’t stare at naked women on our streets, even though there are no naked women on our streets. Better be sure.

Behind all this rebuttal of truth is the Big Lie. It is promoted, cherished and burnished by Donald Trump and those who swallowed his brand of fact-free ideology. The Big Lie is with us and will cast its shadow of pernicious doubt over future elections down through time. The loser will cry fraud and state lawmakers will, under the new scheme of things, be entitled to overturn election results, violating the will of the people to serve their own political goals.

Mark Twain wrote a short essay in 1880 entitled “On the Decay of the Art of Lying.” If Twain were alive today, he might be tempted to retitle his work “The Ascent of the Art of Lying.”

The extraordinary thing about the Big Lie is its blatancy; the fact that it has been found untrue by the courts and by every investigation, yet it rolls on like the Mississippi, unyielding to fact, unimpeded by truth.

The Big Lie is an avalanche of political desire over democratic fact. It introduces corrosive doubt where there is no justification. It is a virus in the body politic that may go dormant but won’t be eradicated. The host body, democracy, is weakened and the infection can flare at any time, triggered by political ambition.

Historically, there have been primary sources of information and tertiary sources of doubt or refutation. For example, some believed that the oil companies were sitting on a gasoline substitute that would convert water to fuel. That is a falsehood that has been spread since the internal combustion engine created a need for gasoline. It was believed by a few conspiracy theorists and laughed off by most people.

When the fax machine came into being in the mid-1970s there were those who thought that the Saudi Arabian regime would fall because information about liberal society was getting into the country. Instead, Saudi conservatism hardened and there was no great liberalization. Today Saudis are online and there is no uprising, no government in exile, no large expatriate community seeking change. Truth hasn’t overwhelmed belief.

It is an awful truism that people believe what they want to believe, even if that requires the suppression of logic and the overthrow of fact. Gradually all facts become suspect, and the lie fights hand to hand with the truth.

As newspaper people joke, “Don’t let the facts stand in the way of a good story.” Democracy isn’t a good story; it is the great story of human governance. And it is being subverted by lies.

Llewellyn King is executive producer and host of White House Chronicle, on PBS. His email is llewellynking1@gmail.com, and he’s based in Rhode Island and Washington, D.C.

Llewellyn King: About the border wall: U.S. immigration policy must be ad hoc

Trump stands in front of a section of border wall near Yuma, Ariz., in June 2020

WEST WARWICK, R.I.

Going to the border and harrumphing won’t solve the very real immigration problem, which pits our humanity against our sovereign entitlement to say what kind of people we are.

We are not alone in this struggle.

The world is on the move. Untold millions of people who live south of our border with Mexico want to move north. Equally untold millions who live in Africa would like to move to Europe; and millions in eastern Europe want to live in western Europe.

From the Indian subcontinent, millions would like to move to Europe, especially to Britain. Millions of East Asians have their eyes set on Australia.

Within these areas, people also are on the move. Millions from Venezuela have flooded their neighboring countries. Likewise in Africa, where war and famine are ever present, people try and walk to a marginally better future in another country. In the Middle East, Jordan and Lebanon are flooded with refugees first from Palestine, then from Iraq and Syria.

As The Economist pointed out recently, a slum in Spain is incalculably superior to a slum in Kenya.

The drivers for migration are poverty, violence, crop failure and political collapse. And persecution, ethnic and religious; for example, the Rohingya in Myanmar have sought refuge in Bangladesh.

The goal of the migrant is the same worldwide: a better, safer life.

The political price paid by the stable democracies continues to be huge. It played a role in Donald Trump’s election and will play a role in the next presidential election, whether Trump runs or not. It was the great driver for Brexit and Britain’s seeming self-harming. It has driven the move of Hungary, under Viktor Orban, to autocracy.

It is hard to stop people who have nothing to lose from crossing a frontier if they can. But they aren’t the only migrants. Some, a small number, are opportunists. These are the migrants who overstay student visas, manipulate qualifications for residence, and willfully circumvent the law or contract so called green card marriages.

But they aren’t what the border crisis is about -- any more than it is what the overloaded boats crossing the Mediterranean Sea is about. It is the physical manifestation of desperation.

Because the migration problem is so complex – human problems are almost by definition complex— it isn’t a matter of resolution so much as management. We want, for example, immigrants with high-tech skills, but we are worried about the impact of millions of desperate peasants walking across the deserts.

Now a new driver of migration has opened: global warming. The heat and drought hitting the U.S. West Coast are also hitting Central America and will affect livability.

Adding to the complexity of the immigration conundrum is the labor shortage. Construction depends on immigrant labor, farming on contract labor, and slaughterhouses and chicken processors can’t stay open without immigrants to do the unappealing work.

One small step forward would be a sensible work permit.

It seems to me that the wall -- Trump’s wall – isn’t a bad thing. It is a declaration, a symbol. It won’t deter desperate people and it won’t end smuggling. The latter is going to get worse with drones and even autonomous aircraft that can bring their lethal cargoes deep into the United States.

While there is an insatiable market for drugs here, smuggling will continue and even increase. And while that is so, lawlessness south of the border will accelerate.

Sadly, despite Vice President Kamala Harris’s statements, we aren’t going to repair the countries to our south overnight. But we might look to repairing our drug policy, seeing if that can be adjusted to take the profit out of the trade. Except for the gradual, local legalization of marijuana, we haven’t contemplated drug management, short of prohibition, in a century. A new look is due.

There is no single policy that is going to solve the human misery south of the border which drives so many to risk their lives or, through love, to send their children north.

Therefore immigration policy will never be a total, sweeping thing, but rather an ad hoc affair: We need some immigrants, we don’t want others; we have big hearts, but we fear immigration that is unchecked.

We fear the political, cultural and social change that immigrants will bring, especially if they are of a common language and background. Pain in Central America is political torture in the United States.

Llewellyn King is executive producer and host of White House Chronicle, on PBS. His email is llewellynking1@gmail.com. He’s based in Rhode Island and Washington, D.C.

Web site: whchronicle.com

Newport's entrepreneurial energy

“‘By 1760 Newport was humming with industry. As one old history states, “Newport was not the headquarters for piracy, sugar, smuggling, rum, molasses and slaves.’’’. But time had worked wonders. There is very little molasses or sugar used there now.’’

— Will M. Cressey, in The History of Rhode Island, published in the 1920’s

Newport in 1818

‘Most important fish in the sea’

Atlantic menhaden

From ecoRI News (ecori.org)

Even though menhaden are eaten by few people, more pounds of the oily fish, often called “pogies” or “bunkers” by New Englanders, are harvested each year than any other in the United States except Alaska pollock.

The Atlantic menhaden fishery is largely dominated by industrial interests that remove the nutrient-rich species in bulk by trawlers to make fertilizer and cosmetics and to feed livestock and farmed fish. Commercial bait companies fish for menhaden to provide bait for both recreational fishing and for the lobster fishery. Recreational fishermen also access schools of menhaden directly and use them as bait for catching larger sport fish such as striped bass and bluefish.

This demand puts a lot of pressure on a species that plays a vital role in the marine ecosystem. For instance, juvenile menhaden, as they filter water, help remove nitrogen.

Conservationists often refer to menhaden as “the most important fish in the sea” — after the title of a 2007 book by H. Bruce Franklin. They believe that menhaden deserve special attention and protection because so many other species, such as bluefish, dolphins, eagles, humpback whales, osprey, sharks, striped bass and weakfish, depend on them for food.

This year’s spring migration of menhaden has brought a large influx of the forage fish into Narragansett Bay. As a result, there has been a marked increase in the number of fishing vessels and fishing activity there, according to the Rhode Island Department of Environmental Management (DEM).

Agency officials said members of its Law Enforcement and Marine Fisheries divisions are closely monitoring this fishing activity.