William Morgan: A medical firm’s lost design opportunity in a very dramatic spot

When can a substandard commercial building be transformed into good architecture? Can a despised icon of second-rate design become a beloved object? More specifically, can the ugly behemoth of University Orthopedics, in East Providence, R.I., overcome the stigma of being just another spec medical box?

University Orthopedics, 1 Kettle Point, East Providence, N/E/M/D Architects.

Photo by William Morgan

Kettle Point, which is also the site of a development of the kind of suburban housing seen near urban interstates everywhere, is a gorgeous promontory with unparalleled views of the Providence skyline, a working waterfront and down Narragansett Bay. If this site were not in the perceived ugly step-sister of East Providence, it would have been one of the most desirable pieces of land in the state. One thinks of what will happen to the neighboring Metacomet Golf Club course, glorious open land with tremendous potential: It will turn into the all-too-familiar faux-Colonial tackiness on a sea of asphalt.

Kettle Point housing development.

— Photo by Will Morgan

On the positive side, University Orthopedics is affiliated with Brown University’s Warren Alpert Medical School and so is one of the parts of Providence’s growing importance as a medical center. And the Kettle Point location offers expansive and maybe healing views of water, trees and skyline. This giant infusion of sunlight and a panorama of nature must surely contribute to the wellness of the patients and the happiness of the staff.

Providence harbor and downtown skyline from Kettle Point.

— Photo by William Morgan

The ugly duckling becomes a swan when a loved one needs treatment for osteoporosis or a broken limb. Then the state-of-the-art facilities and the staff’s training seem more important than aesthetics. But do they need to be mutually exclusive? What if the medical group that commissioned 1 Kettle Point had hired someone besides a value-engineering-minded developer? At the very least, a location this visible demanded a better design than a clunky real-estate container wrapped in cheap materials, one that looks like every other new medical office block from Boise to Little Rock.

Does this signage or the Home Depot-orange cladding symbolize quality medicine and research?

— Photo by William Morgan

A sensitive architect might have at least given 1 Kettle Point a more distinctive skyline. (Please do not whine that a good architect costs too much, as a really smart designer might have even given University Orthopedics a lot more for less.) And given such an environmentally sensitive site, a landscape architect should have been consulted, and maybe allowed to integrate this hulk into its prime surroundings.

Alas, the response in our high-quality (for those who can access it) but often unobtainable, fragmented and even chaotic American health-care system to such concerns is always one of money. What a building looks like seems minor compared to the medicine it delivers. But why not heal the entire patient, while at the same time supporting a quality building that could have been a great advertisement for the practice, for Brown, for Rhode Island?

The handsome lights on the stair compliment the undoubtedly unintentional industrial aesthetic of the metal railings.

— Photo by Will Morgan

Hospital needs, admittedly, dictate their forms. Think of all the university-affiliated and other medical centers that keep spreading across America, with new wings and additions, often in disparate styles. Yet, a handsome example that exists within the jumble of buildings that comprise the main campus of the august Massachusetts General Hospital, in Boston, is the handsome neoclassical original building, designed by Charles Bulfinch. In erecting their signature structure, the hospital trustees chose the architect of both the Massachusetts State House and the U.S. Capitol.

Massachusetts General Hospital, Charles Bulfinch, architect, 1818-23. Wikimedia Commons.

My favorite example of a successful hospital that is also a work of architecture is a tuberculosis sanatorium in rural Finland, designed in 1929 by a then-young Alvar Aalto. Built with limited resources, the sanatorium launched Aalto’s career, but it also became one of the noblest landmarks of modern architecture. The revolutionary aspects of the design were dictated by the treatment of TB, which emphasized abundant sunlight and fresh air. Aalto fashioned draft-less windows and splash-less sinks, along with bright colors and inexpensive furniture that is still being manufactured.

Tuberculosis sanatorium, Paimio, Finland, 1929-33.

— Photo by the Alvar Aalto Foundation.

Why should what University Orthopedics looks like, and how it contributes to or detracts from its environment, be any less important than the layout of its labs and operating rooms? This medical group, presumably, would not accept low professional standards of medicine. So, it is unfortunate that, in the quest for medical integrity, University Orthopedics’ patronage did not aspire to high standards of architectural design

William Morgan has taught the history of modern architecture at several colleges, including Princeton and Roger Williams Universities, and has written extensively on Finnish architecture.

A still, very New England place for reflection, not feasting

On Thanksgiving: In Jaffrey Center, N.H., with Mt. Monadnock in the background. The celebrated novelist Willa Cather is buried in Jaffrey’s Old Burying Ground.

— Photo by William Morgan

Sunday stillness

Sunday Aug. 15 on Trenton Street, in Providence’s Fox Point neighborhood, at the head of Narragansett Bay. This picture recalls the work of American painter Edward Hopper.

--Photo by William Morgan

William Morgan: Joy and sadness with an old knife

My wife, Carolyn, is a potter and a gourmet cook. She depends upon and thus respects her tools, but they are to be used, not objects to be displayed. The tarnished copper pots hanging in a row from a beam above the stove are not there to impress; once in a while I might polish one to a shine, but the pots are there to be worked. The knives on Carolyn's wall rack are beautiful to her. She recalls every country auction where she acquired each pitted and stained Sabatier, and knows how each knick was earned. But these blades still need to be used to slice and chop; they are there to serve.

There is one tool, however, that does not get used. Framed, it occupies a place of honor on our kitchen wall. When we first found this in an antique shop on Wickenden Street in Providence we thought that it was a super-realist still life of a knife. The dealer had no recollection of where he picked this up, but it has a framer's sticker from Springfield, Mass.

A faded typewritten note in Hebrew taped to the back revealed something of its history. Two Hebrew-literate friends gave us this translation:

With G-d's Help.

Tuesday - 8th of the Hebrew Month of Av 1948.

To my esteemed and dearest Avraham May Your Light Shine

Shalom & Blessings

This knife is a gift from your father, of Blessed Memory, that I received from him at the time of my completion of Rabbinic Ordination.

Your father, of Blessed Memory, used this knife to slaughter poultry at the office of slaughter on 19 Franziskaner Street that he inherited from your grandfather Reb Gershon (of Blessed Memory).

And at the opportunity of this pleasant visit it seemed fitting to give this present to one with a delicate and appreciative palate - that it should be your inheritance from your father of Blessed Memory, and that this knife is a symbol of a bygone and disappeared era.

With a warm handshake of appreciation and to your refined wife regards and all the best

Missing you and your family

Where was Franziskaner Street? There may have been hundreds of streets by that name in Germany and parts of Poland and the Ukraine. (Franziskaner is a German word referring to Franciscan monks.) Did Avraham's father escape and did he grab the poultry knife as storm troopers pounded on his father's door? Three years after the concentration camps were liberated, and in the year of the creation of the State of Israel, the knife came to the grandson, now safely in America.

There is both joy and sadness in the knife's coming into our house. How could this tool be anything other than a treasure to be venerated? What descendant could not hold on to this link to past? Yet families can fade into oblivion, while the artifacts of their lives end up in auctions and yard sales. So often the excitement of discovering a discarded gem is tempered by the knowledge that it may well mark the end of a family line.

Reb Gershon's blade for butchering poultry has a special place just above our kitchen table, where we will remember him. Growing up in in rural North Carolina, my wife vividly recalls her mother dispatching chickens with a similar tool. So the knife is a special bond between the butcher shop on Franziskaner Street and our kitchen.

William Morgan, based in Providence, writes on architecture and other topics, mostly design-related.

William Morgan: Book looks at metaphor, imitation, craft and continuity in architecture

One of the New England's most picturesque assets is the Greek Revival house, a sometimes brick but usually wooden structure with some classical details or perhaps even a portico, lining Main Streets and dotting the countryside. Aside from some legends about empathetic associations with Greece's war of independence, the application of a Doric column or the heavy lintel over the doorway was less politics than embellishment. Americans simply liked the style.

Temple form Greek Revival house in Winchendon, Mass., 1845.

— Photo by William Morgan

It is rather for architects and historians, such as Columbia University's Françoise Astorg Bollack, to parse the genealogy and meaning behind these temples of democracy. In her latest book, Material Transfers, Professor Bollack reminds us how the marble temples of ancient Greece were recreations of earlier wooden structures. While Americans built plenty of neoclassical civic structures, it was in the domestic realm that the wooden temple flourished.

The same kind of torturous evolution with multiple iconographic transferences can be seen in other styles, such as the Gothic Revival. A style that paid homage to the masonry forms of the pointed arch and the ribbed vault got translated into Carpenter's Gothic churches or cottages. Bollack also mentions cast iron, a revolutionary material that was molded with Renaissance details and often painted to look like stone.

Rotch House, A.J. Davis architect, New Bedford, Mass., 1845.

— Photo by William Morgan

The French-trained Bollack has done considerable restoration work, but Material Transfers: Metaphor, Craft, and Place in Contemporary is an attempt to redefine the meaning of contextual design. Rather than engaging in a century-old battle between modern and traditional – the angst of replica versus invention, Bollack suggests we discard an "outdated moral opprobrium." She presents us with at 22 projects characterized by "an unorthodox coupling and combination of forms."

Throughout, Bollack addresses such issues as metaphor, imitation, craft, and continuity ("Where are we to find a fresh place for 'the new' within the constraints of longed-for continuity"). The role of historic form in contemporary architecture, and how to respect the "continued validity of the traditional," are significant issues. But beyond the architectural theory, there is much delight to be found in the photographs of the "rich stew of hands-on trial-and-error research, collaboration between architects, manufacturers, and craftspeople."

Material Transfers is replete with serendipity, ingenuity, and the stretching of material limits. In Dairy House in England, glass lies between the horizontal wooden siding. An office block in downtown Copenhagen for a manufacturer of gold beads has a curtain facade of perforated copper that shimmers and changes color by night. A 14-story building in New York City looks just like its neighbors, except that it is made of pressed and carved glass.

The Dairy House, Somerset, England, Skene Catling de la Peña architect, 2007.

Such successful brainteasers include an abstract modern design for winery in Napa Valley, constructed of gabion (loose rubble constrained by wire fencing). A Paris town house is covered with a pixilated photograph of the building next door in a wood resin of the type used for road signs. Rammed concrete is the material of choice for a guest house added to a 1740 German vineyard.

Familiar forms inform many of these examples, but they are often realized in materials that seem wildly unfamiliar. Modernism's chief tenet of originality is stood on its head here, although many of the solutions respect tradition. This book's projects "begin to open the door to shift the discourse's center of gravity towards a more inclusive view of what 'making' is all about."

That said, anyone who is interested in contemporary architecture and how it can be integrated into historical settings, and invigorated with new, mostly non-polemical ideas will reap many visual rewards from this book.

One of my favorites from Material Transfers is the diagrammatical construction in welded galvanized wire mesh of an 1177 Italian basilica that was destroyed by an earthquake in 1233.

Basilica di Rete Metallicca di Siponto, Puglia, Italy, Edoardo Tresoldi architect, 2016.

But the project that really moves me is the Wadden See Center on the west coast of Denmark (the marshland is a UNESCO World Heritage Site) by the ever restrained and environmentally aware Danish designer, Dorte Mandrup. What at first appears to be a bold, modern statement is also a tribute to the local agricultural vernacular, and its roof and walls are surprisingly made of thatch.

Wadden See Center, Ribe, Denmark, Dorte Mandrup architect, 2017.

Françoise Astorg Bollack, Material Transfer: Metaphor, Craft, and Place in Contemporary Architecture, Monacelli Press, New York, 2020, $50.

Providence-based writer William Morgan has a degree in restoration and preservation of historic architecture from Columbia University. His latest book is Snowbound: Dwelling in Winter.

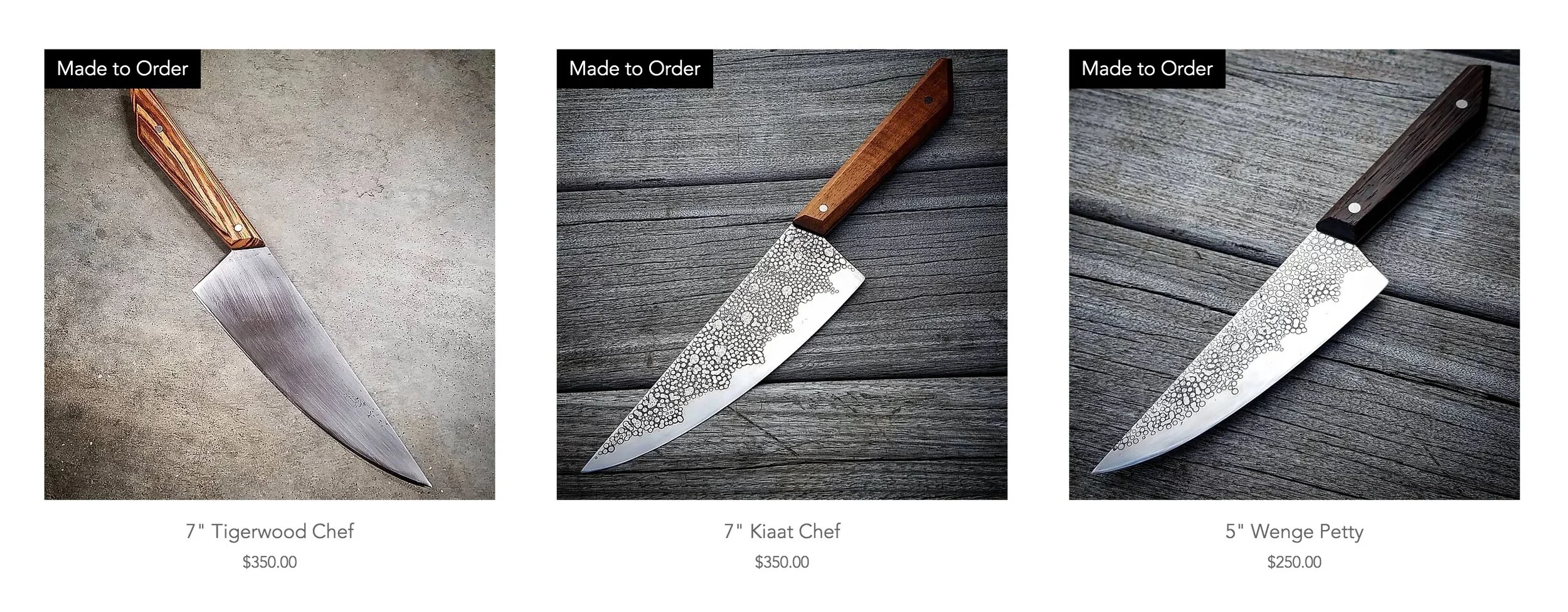

William Morgan: Cutting-edge artisanship at a family homestead in rural Maine

Hannah and Chris Blackburn outside their cutting-tool-making workshop, in New Gloucester, Maine

— All photos by William Morgan

My wife recently bought herself a kitchen knife. Carolyn has dozen of blades suited to all kinds of cooking and pottery, including the stained and pitted Sabatier that she found at a yard sale a quarter century ago. But this piece of cutlery from Maine was different. It cost far more than she could afford, but it was so beautiful, such a work of art, that she could not afford not to buy it.

Really good tools should have stories. Carolyn's new extension of her hand was made of recycled materials: wood from Boston park benches and metal from old saw blades (the recycled 19th Century carbon steel is much stronger than anything available now, and its hard-earned patina is beautiful). That these artisanal tools are sold only at two stores –Strata in Portland and Stock in Providence – reinforces the fact that they’re the products of true craftspeople.

The Blackburns use the steel from old saw blades to make their artisanal knives and other cutting tools.

Full Circle CraftWorks is the commercial face of two art school graduates, trying to build a business while raising a family on a 22-acre homestead in New Gloucester, Maine, a quiet upland town close to, but very different from Freeport, best known for L.L. Bean and other stores, many of them outlets of national chains.

Hannah and Chris Blackburn met as undergraduates at the Rhode Island School of Design, where they were furniture and sculpture majors, respectively. They mastered such skills as welding and sculpting, along with traditional woodworking. Maine native Hannah grew up in nearby Yarmouth, while Chris hails from suburban Washington, D.C. After graduation, the couple remained in the Rhode Island capital.

Providence is a good place for young artists, with lots of colleagues and abundant studio space, but its urban setting was not what the Blackburns wanted for their growing family of two girls and a boy. "The goal was to carve out a simpler life," Chris says, "more directly connected to the environment, the seasons, and all things that sustain our life." One grace note is that the quest for a life based on the land while producing beautiful utilitarian objects is not so different from that espoused by the Shakers, whose last active colony, Sabbathday Lake, is close by in New Gloucester.

Carolyn Morgan and Chris Blackburn in First Circle’s workshop

Their 1985 log cabin on a dirt road came with a two-stall horse barn, which they converted into a workshop, complete with enough of the tools needed to fashion the exotic woods from around the world and the redundant saw blades from barns and country auctions into their handsome tools.

The future success of Full Circle would let these artists live from their sales, but right now their main goal is raising a family on what they hope will become a thoroughly sustainable operation. As a result, much of their life is focused on the rigorous, endless day-to-day and seasonal activities of a working farm.

Just a mention of the Full Circle’s livestock – three goats, seven ducks and a score of chickens, guarded by a dog to guard against coyotes, bears and other predators – ought to be reminder enough that self-sufficient farm life is far from simple or romantic. In the spring, piglets, turkeys and more laying hens augment the permanent stock. Bow hunting deer in the autumn provides much of the family's meat.

There is a small greenhouse, a fruit orchard and gardens for a variety of crops that will grow in Maine. The house and workshop are heated solely with firewood harvested on the property, where sugar maples are tapped to make syrup. Through all the seasons the three young children, aged nine, seven and five, help with chores, from planting and harvesting, to stacking firewood and feeding the animals.

Demanding as farm life is, it does not preclude the family's engagement with the local community. The Backburns host an annual July pig roast that draws scores of friends and neighbors. Their two daughters act in plays put on by the local youth theater, where Chris is a set designer and member of the build crew. The Blackburn children go to a Montessori-type charter school, even as important life lessons come from being part of the agricultural enterprise that helps sustain them.

A hand saw once used in Massachusetts apple orchard or a large circular blade from a Vermont sawmill, along with wood repurposed from repairing their cabin's porch or from an Indonesian rainforest, are transformed into utilitarian but strikingly handsome tools. Whether Hannah and Chris are fashioning a cleaver or a chopping blade, their handmade tools express a worldview that respects the land and the dignity of hard work.

When Chris saw Carolyn's knife again, he said, "It's getting good use; I can tell by the patina. I much prefer that. Some people see them as precious, but tools need to be used."

William Morgan, based in Providence, is an architecture writer, essayist and photographer. His latest book is Snowbound: Dwelling in Winter

Sabbathday Lake Shaker Village, in New Gloucester. It was founded in 1783 by the United Society of True Believers at what was then called Thompson's Pond Plantation. Today, the village is the last of some over two-dozen religious societies, stretching from Maine to Florida, to be operated by the Shakers themselves. It comprises 18 buildings on 1,800 acres.

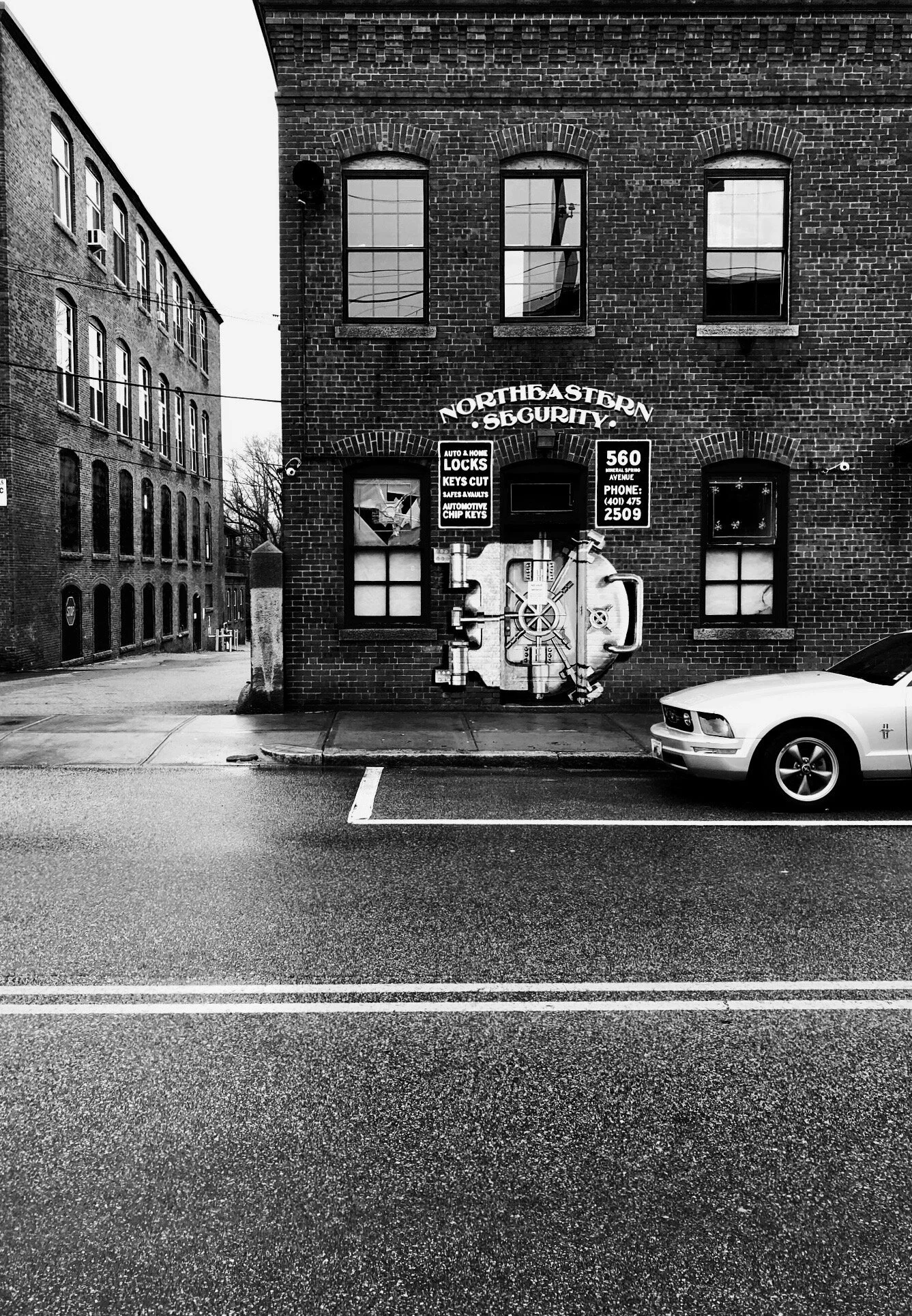

William Morgan: A haunted grandstand in Pawtucket

The stands of what had been Narragansett Park

— Photo by William Morgan

Just off the unspeakably grim Newport Avenue strip, in Pawtucket, R.I., an abandoned colossus reminds us of once glorious days of thoroughbred horse racing patronized by swells from Newport and New York. This enormous structure was once part of a 200-acre complex with barns that housed 1,000 horses.

Narragansett Park opened in 1934, after the state’s official airport was declared to be Hillsgrove Airfield (now T.F. Green Airport), in Warwick, instead of Pawtucket’s What Cheer Airport, and pari-mutuel betting was reinstated after a 30-year ban; it folded in 1978 after a disastrous fire that killed three-dozen horses. The grandstand then became Building #19, the odd-lots warehouse, or "America's laziest and messiest department store," as its founder Gerry Elovitz dubbed it.

The slide from society amusement (thoroughbreds such as Whirlaway and Seabiscuit raced here on its mile-long oval), and a "Retail Derby" against the big-box stores, to inevitable decay, reverberates with the last days of our totally corrupt, would-be Nero-style emperor. Reminding us of Rome's Circus Maximus, home of the great chariot races, Narragansett Park's haunted grandstand is apt metaphor for the end of 2020.

William Morgan is a writer, architectural historian and photographer based in Providence. He has written on stock-car racing for The New York Times. His latest book is Snowbound: Dwelling in Winter.

Postcard photo of Narragansett Park in the 1950s

Work goes on after the storm

Southeastern New England’s first snowstorm of the month ended late in the day on Dec. 17, when the dramatic skies – looking like a 19th-Century Romantic landscape painting –announced a change in the weather. Life went on, as it always has during a New England winter. Two large ships were in Providence’s harbor: a tanker unloading oil to East Providence and the cranes on the other vessel being used to load something, perhaps scrap metal.

Photo and caption by William Morgan, a Providence-based writer and photographer. His latest book is Snowbound: Dwelling in Winter.

William Morgan: Looking lithographically at proud 19th Century Maine

As part of its celebration of the 200th anniversary of Maine statehood, the Bowdoin College Museum of Art last winter held an exhibition of lithographs of 19th-Century town views in the Pine Tree State. Since then, the college and Brandeis University Press have published a handsome oversize book, Maine's Lithographic Landscapes: Town and City Views, 1830-1870.

What it says above:

“View of Portland, Me./Taken from Cape Elizabeth before the great conflagration of July 4th 1866

“Tinted lithograph from a photograph taken by Edward F. Smith and published by B.B. Russell & Co., Boston. 1866. ‘‘

The author is Maine State Historian Earle G. Shettleworth Jr., who was the state's historic-preservation officer for nearly five decades. The modest and scholarly Shettleworth may well know more about the state's architecture and other art than anyone else. Devoting his life to documenting everything Maine, he has written and lectured prodigiously on every aspect of Maine's built environment, and also written studies of female fly fisherman, photographers, painters, and parks.

“Augusta, Me., 1854.

Drawn by Franklin B. Ladd. Tinted lithograph by F. Heppenheimer, New York.’’

In a bit of Maine understatement, the co-director of the Bowdoin Museum, Frank H. Goodyear Jr., writes, "In Nineteenth Century America, the printed city view enjoyed wide popularity." As Shettleworth notes, the prints helped "forge the young state's identity” and served as "expressions of pride of place’’. During the period under review many towns and cities across America were memorialized in printed images drawn by artists famous and unknown.

Still, Maine was still a small state in the back of beyond. (its population was under 300,000 at the time it separated from Massachusetts, in 1820.) Thus, what the book’s creators call the "first comprehensive record of urban prints during the first fifty years of statehood" is somewhat limited: There are a total of 26 views of 11 places. Those are augmented by a score or more images of the often somber Bowdoin campus, including a painting, old photos, and two Wedgwood plates. Groundbreaking as the book is, viewing the exhibition itself would probably be more satisfying.

That said, Maine's Lithographic Landscapes is a handsome production. The Bowdoin Museum has a history of elegant catalogs, and this co-operative venture with Brandeis demonstrates that press's growing role as a publisher of New England studies. I am not sure that anyone looks at colophons (publisher’s emblems) anymore, so it is worth noting that the book was designed by the eminent book designer, Sara Eisenman.

Earle G. Shettleworth, Jr., Maine's Lithographic Landscapes, Brandeis University Press, 2020, 144 pages, $50.

William Morgan is a Providence-based architectural historian, photographer and essayist. His latest book is Snowbound: Dwelling in Winter.

While there’s still snow

This long poem, by Whittier (1807-1892) a poet based in northeast Massachusetts, a Quaker and an abolitionist, once was required reading for kids.

Adapted from Robert Whitcomb’s “Digital Diary,’’ in GoLocal24.com

Providence-based architectural writer and historian William Morgan’s latest – and beautifully illustrated -- book, Snowbound: Dwelling in Winter (Princeton Architectural Press), looks at 20 houses in various cold parts of the world, including Europe, Asia and North and South America.

A New Hampshire house and a Connecticut house are featured in the book.

As the press release notes:

“From the ski slopes of Utah to the frigid tundra of northwestern Russia, Snowbound celebrates contemporary design in cold climates with a focus on sustainability. Tailor-made for architects, designers, snowbirds, and aspiring second-home owners, this tour of twenty dwellings is equal parts escapist photo essay and practical sourcebook, with immersive photography, architectural plans, and location, climate, and building-systems data.’’

That some of these houses were put up in preposterously harsh and remote places adds to the entertainment.

But global warming rears its head. Mr. Morgan writes:

“Candidates for Snowbound in Canada, Australia, and Vermont had to be eliminated as recent winters came with less-than-usual snowfall. In the middle of the winter in the Southern Hemisphere, there was insufficient snow in the Andes, more than a thousand miles south of Buenos Aires, to photograph a house as it would have looked only less than a decade ago.’’

But what about summers at these buildings?

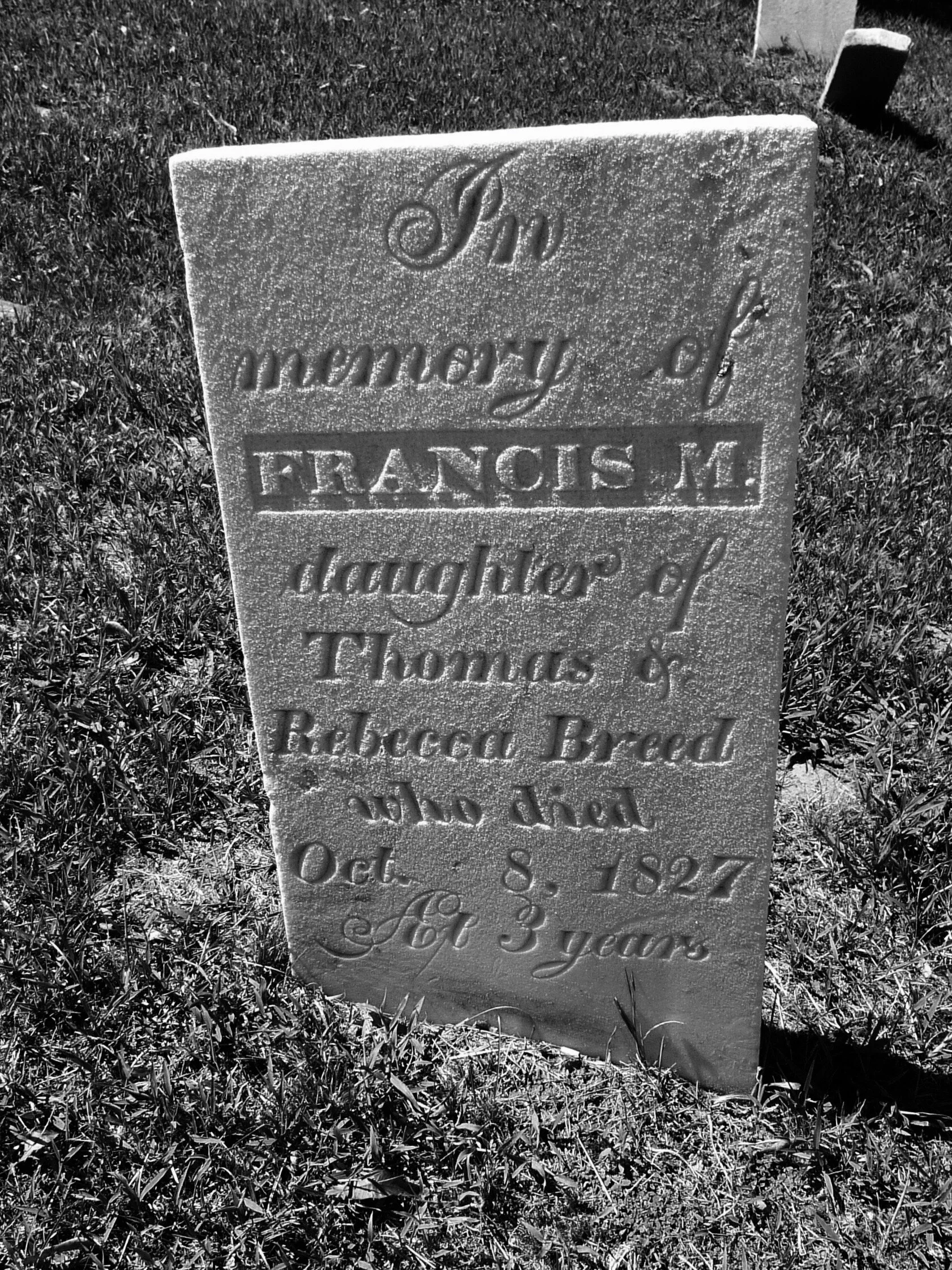

William Morgan: When so many deaths were early

The Stonington Cemetery, in Stonington, Conn. The first burial in it was in 1754, with the interment of Thomas Cheseborough.

Francis Breed was three when she died, in 1827. The stone carver had a penmanship flourish.

Stand in any old New England cemetery and you’re surrounded by premature death. Living along New England's rocky shores in the 18th and 19th centuries meant a constant range of childhood diseases, some spread in pandemics, such as measles, diphtheria and smallpox, if mother and infant survived childbirth, and the other maladies and dangers that often made life brutal and short.

Within a radius of a dozen feet in this handsome necropolis just north of Stonington Borough, there are several reminders of loss in a pre-vaccine world.

Samuel and Alzayda Robinson's son William left this life at 18 months, but with no fancy inscription, just simply: “DIED’’.

Charlotte Augusta Staples, aged one year and seven days, had the same carver as William Robinson nearby, but here with this inscription:

“Happy infant early blest/

Rest in peaceful slumber rest’’

Captain Joseph Eells, born in 1768, got a 19th-Century stone. Perhaps Eells was lost at sea.

Saddest of all, Lydia Palmer was a young wife when she she died (giving birth?) at only 18. Her weeping willow, carved in porous sandstone, is eroding. The inscription here reads:

“Behold & see as you pass by,

As you are now so once was I,

As I am now so you must be,

Prepare for death & follow me.’’

William Morgan is a Providence-based architectural historian and essayist. His latest book, Snowbound: Dwelling in Winter, will be published next month.

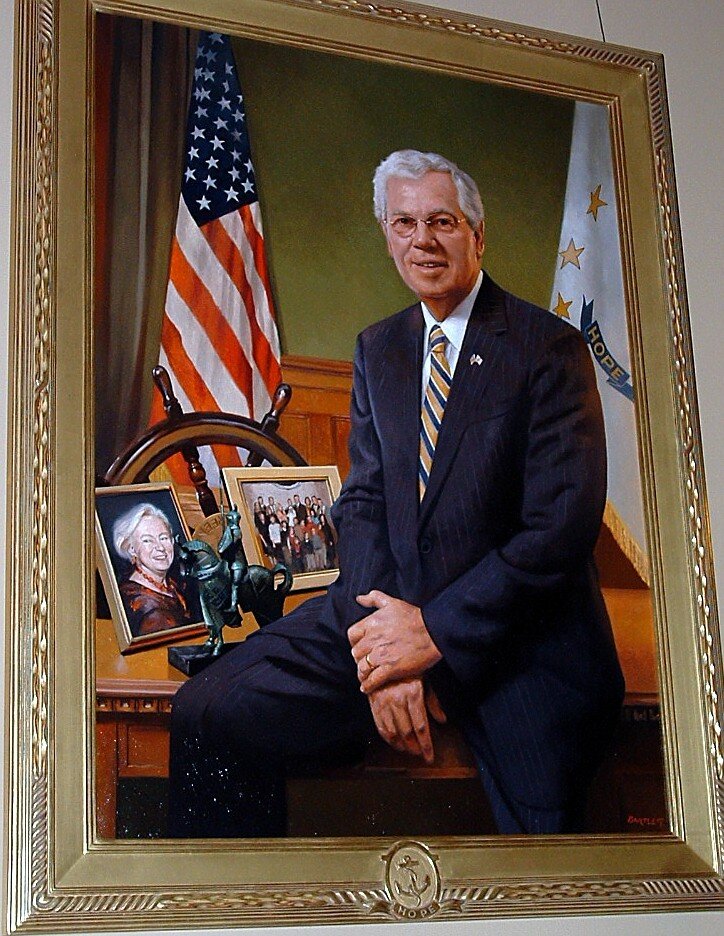

William Morgan: Public art — banality and grandeur

Rhode Island Gov. Gina Raimondo commissioned a poster that would honor the dedication, sacrifice and nobility of medical workers during the COVID-19 pandemic.

That the Sheppard Fairey poster, entitled "Rhode Island Angel of Hope and Strength," has been maligned by Republicans, who see it as "an image of Communist propaganda,’’ is less surprising than that it was commissioned by the state's canny chief executive.

Workers Monument in front of the Soviet Pavilion at the 1937 Paris Expo

State-sponsored art is rarely memorable, whether a monument to heroes of the Soviet Union or an official presidential portrait (remember the 1965 painting of Lyndon Johnson by Peter Hurd, which LBJ declared "the ugliest damn thing" he'd ever seen). Our postage stamps and coinage are generally nothing to write home about either.

Official portrait of former Rhode Island Gov. Donald Carcieri, which is so realistic that it looks like a photo; the various trappings of office and private life are displayed, as if the man alone were not enough.

Rhode Island School of Design alumnus Fairey is best known for his now iconic 2008 Obama campaign poster, simply labeled HOPE. The Rhode Island Angel's graphic style comes from a long tradition of jingoistic American posters, particularly those from World War I. (“Hope” is the official Rhode Island motto.)

1918 War Bonds poster.

Our COVID-19 angel is pretty tame, especially compared to the public art produced by totalitarian regimes. Both Fascists and Communists almost always revert to the same sort of school textbook realism.

The similarity of different totalitarian regimes' art: Hitler and Stalin as benign fatherly figures.

The issue here is not really one of a partisan polemic (workers of all political stripes wear similar jackets and caps) but the unfortunate tendency of governments to support a flaccid realism.

Irish Famine Memorial in downtown Providence is a tribute to banality – the most simplistic imagery.

— Photo by William Morgan

It may be that government-supported public art, particularly statuary, is oxymoronic. But if we are going to have it, it needs to rise above triteness — for example, of the proposed Dwight Eisenhower monument in Washington — and at least aim for something noble or transcendent.

Proposed statuary for the Eisenhower Memorial in Washington. This D-Day tableau is modeled after a photograph, but this lacks that famous image's immediacy and poignancy.

Red Army Memorial in Sofia, Bulgaria. This has a lot more life than the proposed Eisenhower statute; It’s Soviet Realism at its powerful best.

The curse of such memorials is a sense of literalness, although we get some credit for quickly abandoning the European precedent of portraying our leaders in classical garb.

George Washington in the North Carolina Capitol, by the Italian neoclassical sculptor, Antonio Canova, 1821.

— Photo by William Morgan

It seems unlikely that the sort of politico that conflates flag waving with patriotism will actively encourage any sort of abstraction, as so unlikely but did brilliantly happen with the Vietnam Memorial in Washington.

In an age of all kinds of visual media, perhaps it is time to search for more eloquent and sophisticated expressions of commemoration and grief.

Until that time, we can remember the golden age of public art in this country, the period from the Civil War (which demanded a lot of statuary) to the Great War.

Augustus Saint-Gaudens, Shaw Memorial, Boston, 1884-97.

— Photo by William Morgan

Augustus Saint-Gaudens, arguably the greatest sculptor whom American has produced, understood the difference between verisimilitude and a powerful naturalism. Saint-Gaudens's monument to Col. Robert Gould Shaw and the black soldiers of the 54th Massachusetts Regiment opposite the State House in Boston remains one of the most moving works of American art.

Shaw Memorial, detail.

— Photo by William Morgan

Saint-Gaudens also designed the so-called "double eagle" $20 gold piece at the behest of his friend Theodore Roosevelt. Liberty depicted on the coin – and soaring above Colonel Shaw – is the distant ancestor of the Rhode Island Angel of Hope.

William Morgan is a Providence-based architecture writer. His next book, Snowbound: Dwelling in Winter, will be published by Princeton Architectural Press this autumn.

The latest New England campus architecture

Business Innovation Hub at UMass, Amherst; new Design Building to the left.

Photo by Bjarke Ingels Group

Architectural critic and historian Willliam Morgan has written an exciting column, with splendid photos, in GoLocal24.com about some new campus architecture in New England. It’s a very nice tour d’horizon.

To read Mr. Morgan’s piece, please hit this link.

William Morgan: Big box bathos in Fall River

Closed BJ’s Wholesale Club in Fall River. Photos by William Morgan

As if the hard luck mill city of Fall River, Mass., did not suffer enough existential angst, the failure of a big box store, such as BJ’s Wholesale Club, off Quequechan Avenue and with its prominent “Store Closed” banner, serves as a constant reminder of struggle. The hunkered down sea gulls might as well be vultures. But turn your back on BJ’s carcass and there’s the largest box store of them all, Walmart.

The Bentonville, Ark.-based commercial behemoth, has sucked the life out of Main Streets all across America, and arguably spelled the doom of BJ’s. Bigger and cheaper (in both senses of the word) than a score of older Spindle City businesses that it supplanted, this particular box store is touted as a Walmart Super Center. Fall River has some of the largest and emptiest parking lots around, reminders of the vain hope that massive shopping centers would save this once heroic economic powerhouse. These asphalt deserts are infertile ground indeed.

Looking toward Walmart Super Center in Fall River

Providence-based architectural historian, book author, essayist and photographer William Morgan was for many years the chairman of the Kentucky Historic Preservation Review Board.

Editor’s Note: Ironically, perhaps, Amazon has a big distribution center in Fall River. Amazon, of course, has ravaged many brick-and-mortar stores.

William Morgan: Emlen book goes beyond the stereotype of the Shakers

The United Society of Believers in Christ's First and Second Appearing are among the most beloved – and thus most mythologized – religious groups in American history. The Shaking Quakers or Shakers, as we call them, are usually remembered for their vows of celibacy and their proto-Modern design.

Shaker Sisters at Canterbury, N.H., circa 1893. All pictures are from Imagining the Shakers.

This stereotype does not do them justice, because while adhering to their tenets of simplicity, apartness, and prayer, they also managed to be remarkably efficient farmers and businesspeople. Even while having to depend upon recruits instead of future generations, the Shakers managed a widespread agricultural enterprise, along with furniture making, emanating from communities from Maine to Kentucky. There was much more that was worldly about these entrepreneurs than exquisite rocking chairs and efficient wood stoves.

Shaker Village, Enfield, Conn., in 1834

Robert P. Emlen's Shaker Village Views of 1987 remains a classic among a cottage industry of Shaker books. Now, the retired curator of Brown University collections and a former Rhode Island School of Design professor, Emlen has published one of the most intriguing books on the Shakers ever: Imagining the Shakers: How Visual Culture of Shaker Life was Pictured in the Popular Illustrated Press of Nineteenth-Century America (R.W. Couper Press, 2019, $45; R.W. Couper Press is part of Hamilton College, in Clinton, N.Y.)

Emlen, who once lived with the last surviving Shakers at their farming village in Sabbathday Lake, Maine, has gathered every known engraving or lithograph about the Shakers between 1830 and 1880. There are a few photographs, plus advertisements of the Shakers’ own and some Shaker-themed products.

Advertisement in the Maine Farmer, 1890

Fascinating and important to furthering our understanding of the Shakers, this is the sort of book that needed the support of a university press. In this case, the committed publisher is at Hamilton College, and they earn high marks for a very handsome production.

Shaker Pickles label, circa 1880-85

William Morgan, an architectural historian and a columnist, is the author of, among other books, American Country Churches, which includes a chapter on the Shaker settlement at Sabbathday Lake, Maine.

Print against the tide

At the entrance of David R. Godine Inc.’s warehouse, in Jaffrey, N.H.. Godine is a small, high-end book publisher based in Boston and famed for both the content of its books and for their physical beauty.

— Photo by William Morgan

William Morgan: The utilitarian and the romantic in the Granite State

A 50-cent picture found in a junk store in Warren, R.I., is the ultimate Granite State winter pin-up. On the rear, penned in real ink, is the legend: “Sue Nardi on Snowplow/South Lyndboro, N.H./Feb. 12, 1950’’

Lyndeborough is a small upland village in southwestern New Hampshire, just above where Stony Brook joins the Souhegan River, which provided power for the 19th-Century textile mills at Wilton, N.H.

The image was printed in someone’s basement or in a school darkroom, as the edges of the image are not parallel. My guess is that this is probably a yearbook photograph.

It is more romantic, however, to imagine that the photographer was Sue Nardi’s adoring boyfriend. (Valentine’s Day was just two days away.)

The fetching Italian-American dressed up for this glamour shot. Despite the snow, she is wearing penny loafers and her trousers are seriously ironed. (Feb. 12 of that year was a Sunday, but surely Miss Nardi would have worn a dress to Mass?)

If still with us, Sue would be around 90 – perhaps still treasuring memories of posing against that essential northern New England implement, a snowplow.

William Morgan is an essayist and architectural historian. He is the author of Monadnock Summer: the Architectural Legacy of Dublin, New Hampshire. His next book, Snowbound: Dwelling in Winter, will be published next year by Princeton Architectural Press.

Lyndeborough Town Hall, built in 1846.

Wilton Woolen Co. mill in 1912. There were lots of woolen mills in New England, originally because it was prime sheep-raising country and New Englanders needed wool to keep warm in the region’s long cold season.

New England Merino sheep, famed for the quality of their wool. Merino sheep were introduced to Vermont in 1802. By 1837, 1 million sheep were in the state. But the price of wool dropped to 25 cents/pound in the late 1840s. The state could not handle more efficient competition from other states, and sheep-raising in the Green Mountain State collapsed. Still, it was a bonanza for decades.