Video: 'Satanic mills' in two 'green and pleasant' lands

Arlington Mills, Lawrence, Mass., in 1907

A view of the Berkshires from near North Adams, Mass.

— Photo by jbcurio

Below is a local version of the weird, haunting English poem by William Blake called “Jerusalem,’’ written about 1804. It has long been best known as the hymn of the same name, with music written by Sir Hubert Parry, in 1916. (Remember the movie Chariots of Fire?)

Timmy May, of Newport, R.I., came up with the idea of inserting "New" before “England’’ in the three places where “England” appears in the original Blake poem.

The Industrial Revolution brought many, many “dark satanic mills,’’ first to England and then to its offspring.

Mr. May is on the left in the video below. The other musicians are Jamie Lawton, on violin, and Gregory Jonic, on uilleann pipes.

A very comfortable faith

The superyacht Azzam, which from 2013 to 2019 was the largest private yacht in the world.

For N.T.

The path to joy is faith in God,

The young man told his friend.

His joy was plain upon his face;

He hoped not to offend.

All night they talked, and on the morn,

When day dawned bright and hot,

He shook her hand and wished her well

And set out on his yacht.

By Felicia Nimue Ackerman, a poet and a Brown University philosophy professor. This poem is slightly revised from one that ran in Free Inquiry.

Harbour Court, the Newport, R.I. headquarters of the hyper-exclusive New York Yacht Club

Wave action at Rough Point

The Rough Point mansion from Newport’s Cliff Walk.

From Robert Whitcomb’s “Digital Diary,’’ in GoLocal24.com

It’s nice when artists and others use New England’s innumerable beautiful outdoor spaces for exhibitions.

Thus it is with artist Melissa McGill’s coming show “In the Waves’’ at Newport’s Rough Point (which we used to call Rough Trade), the estate of late and deeply eccentric, indeed creepy (but philanthropic!) billionairess Doris Duke.

Ms. McGill has put out a call for young people to participate in the show, set for next month and meant to focus attention on global warming-caused sea-level rise and other man-caused environmental issues. Dodie Kazanjian, the founder of Art & Newport, is the curator of the exhibition.

This spectacle involves Ms. McGill painting waves on fabric made out of recycled plastic pulled from the ocean; plastic pollution has become a huge menace to sea life. The young people participating in the spectacle will use handles at the ends of long fabric strips to create motion to mimic that of waves.=

“I’m painting the waves in a very expressive way, with the different colors that reference the ocean at Rough Point,” Ms. McGill told the Newport Daily News’s Sean Flynn, in a fun article. “I have done studies and research so they really evoke the ocean there.” (Does the ocean at Rough Point really look that much different than the ocean anywhere?)=

For more information, please hit this link.

xxx

Coastal flooding in Marblehead, Mass., during Superstorm Sandy on Oct. 29, 2012

xxx

As the seas rise, more and more people will have to move back from the shore and abandon their homes on land that’s increasingly vulnerable to flooding. That land will be left as a buffer to mitigate damage from storms. How much of it can be turned into public open space, as parks, bringing something good from the situation?

By the way, although it was published back in 1999, Cornelia Dean’s prescient book Against the Tide: The Battle for America’s Beaches, remains a dramatic, prescriptive (and often alarming) guide to the issues around rising seas and coastal development. Ms. Dean, the former New York Times science editor, continues to study the not-very-slow-motion coastal crisis.

Is elite club crisis silly?

Bailey’s Beach Club in 2012, with “Rejects’ Beach’’ in the foreground, soon after Superstorm Sandy. You can safely predict that a major hurricane will destroy the club’s facilities.

— Photo by Swampyank

From Robert Whitcomb’s “Digital Diary,’’ in GoLocal24.com

The latest controversy over U.S. Sen. Sheldon Whitehouse’s association with the elite, WASPy Bailey’s Beach Club, in Newport, has gone viral after being launched by GoLocal. (I prefer the silly-sounding real name of the club – the Spouting Rock Beach Association.) His wife is a member.

I don’t care much about politicians’ associations in their private life; it’s their public-policy positions that primarily interest me. But I suppose that any story about Newport’s summer creatures, blue-blooded or otherwise, has its allure. Many folks consider Newport an exotic place.

Jack Nolan, Bailey Beach’s general manager, told The Boston Globe that the club’s members and their families have included people of “many racial, religious, and ethnic backgrounds from around the world who come to Newport every summer.” Remarkable, if true…. In any event, for decades the club had reputation of being all white as well as anti-Semitic. Since it’s a private social and recreational organization it presumably doesn’t have to identify its members.

I have no idea what the club’s current diversity is or how it might change. It’s not in my solar system.

The first of a couple of times I went there was as a guest of the late Rhode Island Gov. Bruce Sundlun, who was Jewish. I also remember a couple of kids of color playing on the beach – a member’s grandchildren?

The beach itself is not very attractive – gray sand and, when I was there, ridges of seaweed with bugs flying over them. And the current clubhouse was uninteresting. It will probably be destroyed by the next big hurricane. But all was quiet and low key.

As with most membership clubs, the members clearly like being in a place where they know most everybody, including the staff, which treats them in a way recalling domestic servants. Very cozy and soothing. And for public servants such as Senator Whitehouse it must be pleasant to be in a place whose genteel tradition discourages harassing fellow members over politics or indeed anything else

Back when I was a newspaper editor I noticed that when I had a business lunch with a politician or other public figure, we were less likely to be bothered at a club than at a restaurant. And many people enjoy being taken to a meal at clubs, away from the clatter and crowds of restaurants.

No wonder such institutions are a refuge for the privileged

There are now far fewer clubs around that are overtly discriminatory than a few decades ago. Back then the bias at the old WASP clubs, many of which were founded in the late 19th Century with money made in the Industrial Revolution, led to creation of golf, yacht and other clubs that catered to America’s newer groups. So there were “Jewish country clubs,” “Italian country clubs,” “Irish country clubs,’’ and so on. Of course, racism generally kept Black people out of fancy clubs.

I can remember when Roman Catholics were excluded from many old golf clubs and yacht clubs in New England towns, in one of which I grew up in. The election of John F. Kennedy to the presidency helped open them up. In the end, the old clubs needed the initiation fees and dues money from “new” groups that were rising socio-economically.

Around here, I’ve only been a member of one club – the Providence Art Club, whose 16 co-founders (in 1880) included 10 men, including the distinguished African-American painter Edward Bannister, and six women. I’m no longer a member, though my wife, a painter, is. The club has a public educational and cultural mission, by the way.

Folks will always tend to coalesce into groups with whom they share certain background elements, attitudes and social behaviors. So clubs like Bailey’s Beach won’t go away, though they’ll change their memberships as America’s demographics change. They’ll need the dues money.

Meanwhile, given that the U.S. Senate is mostly a white male millionaires’ club, I’m sure that others besides Sheldon Whitehouse have some connections with exclusive (ethnically or otherwise) institutions. The GoLocal stories might lead media around the country to check into them. The voters can decide how important or trivial these associations are in the broad scheme of things.

Newport's entrepreneurial energy

“‘By 1760 Newport was humming with industry. As one old history states, “Newport was not the headquarters for piracy, sugar, smuggling, rum, molasses and slaves.’’’. But time had worked wonders. There is very little molasses or sugar used there now.’’

— Will M. Cressey, in The History of Rhode Island, published in the 1920’s

Newport in 1818

The nine cities of Newport -- from 'beautiful' to 'nearly squalid'

The private Redwood Library and Athenaeum, in Newport

“I found— or thought I found — that Newport, Rhode Island, presented nine cities, some superimposed, some having very little relation with the others — variously beautiful, impressive, absurd, commonplace, and one very nearly squalid.’’

__ Thornton Wilder (1897-1975), American playwright and novelist, in his last novel, Theophilus North (1973), based on his time in “The City by the Sea’’ as a tutor in 1926

Roger Warburton: An affordable plan to reach net-zero greenhouse-gas emissions

The shore of Easton’s Point, in Newport. The neighborhood is very vulnerable to flooding associated with global warming.

— Photo by Swampyank

From ecoRI. org

NEWPORT, R.I.

It has been known for sometime that a reduction in greenhouse gases would have significant public-health benefits: less pollution means fewer deaths, fewer emergency room visits, and a better quality of life.

It’s also well known that reducing greenhouse gases would decrease the financial damages from hurricanes and storms, from droughts, and from coastal flooding.

The question, until now, has been: How do we pay for the necessary infrastructure changes?

A recent Princeton University study, Net-Zero America, presents a practical and affordable plan for the United States to reach net-zero greenhouse-gas emissions by 2050.

Although it’s a massive effort, the plan is affordable because it only demands expenditures comparable to the country’s historical spending on energy.

“We have to immediately shift investments toward new clean infrastructure instead of existing systems,” according to Jesse Jenkins, one of the project’s leaders.

The plan is also practical, because it uses existing technology. No magic tricks are required.

The plan is also remarkably detailed with analyses at the state and, sometimes, at the county level. For example, the report includes an estimate of the increase in jobs in Rhode Island if the plan were to be implemented.

In nearly all states, job losses in the fossil-fuel industry are more than offset by an increase in construction and manufacturing in the renewable-energy sector.

The motivation behind the recent study is clear: Climate change is “the most dangerous of threats” because it “puts at risk practically every aspect of our material well-being — our safety, our security, our health, our food supply, and our economic prosperity (or, for the poor among us, the prospects for becoming prosperous).”

The challenges are not underestimated: the burning coal, oil, and natural gas supply 80 percent of our energy needs and more than 60 percent of our electricity. Their greenhouse-gas emissions can’t be easily reduced or inexpensively captured and sequestered away.

The plan

The Net Zero America study details the actions required to achieve net-zero emissions of greenhouse gases by 2050. That goal is essential to avert the costly damages from the climate crisis.

The study highlighted six pillars needed to support the transition to net-zero:

End-use energy efficiency and electrification/consumer energy investment and use behaviors change (300 million personal electric vehicles and 130 million residences with heat pump heating).

Cleaner electricity (wind and solar generation and transmission, nuclear, electric boilers and direct air capture).

Bioenergy and other zero-carbon fuels and feedstocks (hundreds of new conversion facilities and 620 million t/y biomass feedstock).

Carbon dioxide capture, utilization, and storage (geologic storage of 0.9 to 1.7 giga tons CO2 annually and capture at some 1,000 facilities).

Reduced non-CO2 emissions: (methane, nitrous oxide, and fluorocarbons).

Enhanced land sinks (forest management and agricultural practices).

One of the study’s key findings is that in the 2020s all scenarios create about 500,000 to 1 million new energy jobs across the country. There are net job increases in nearly every state.

The pathways

The plan outlines five distinct technological pathways that all achieve the 2050 goal of net-zero emissions.

The authors don’t conclude which of the pathways is “best,” but present multiple, affordable options. All pathways only require investment and spending on energy in line with historical U.S. expenditures; around 4 percent to 6 percent of gross domestic product (GDP). The five pathways are:

High electrification: Aggressively electrifying buildings and transportation, so that 100 percent of cars are electric by 2050.

Less high electrification: This scenario electrifies at a slower rate and uses more liquid and gaseous fuels for longer.

More biomass: This allows much more biomass to be used in the energy system, which would require converting some land currently used for food agriculture to grow energy crops.

All renewables: This is the most technologically restrictive scenario. It assumes no new nuclear plants would be built, disallows below-ground storage of carbon dioxide, and eliminates all fossil-fuel use by 2050. It relies instead on massive and rapid deployment of wind and solar and greater production of hydrogen.

Limited renewables: This constrains the annual construction of wind turbines and solar power plants to be no faster than the fastest rates achieved in the United States in the past but removes other restrictions. This scenario depends more heavily on the expansion of power plants with carbon capture and nuclear power.

In all five scenarios, the researchers found major health and economic benefits. For example, reducing exposure to fine particulate matter avoids 100,000 premature deaths, which is equivalent to nearly $1 trillion in air pollution benefits, by midcentury compared to the “business-as-usual” pathway.

Wind and solar power, along with the electrification of buildings — by adding heat pumps for water and space heating — and cars, must grow rapidly this decade for the nation to be on a net-zero trajectory, according to the study. The 2020s must also be used to continue to develop technologies, such as those that capture carbon at natural-gas or cement plants and those that split water to produce hydrogen.

“The current power grid took 150 years to build. To get to net-zero emissions by 2050, we have to build that amount of transmission again in the next 15 years and then build that much more again in the 15 years after that. It’s a huge change,” according to Jenkins.

Roger Warburton, Ph.D., is a Newport, R.I., resident. He can be reached at rdh.warburton@gmail.com.

References: Net-Zero American, E. Larson, C. Greig, J. Jenkins, E. Mayfield, A. Pascale, C. Zhang, J. Drossman, R. Williams, S. Pacala, R. Socolow, EJ Baik, R. Birdsey, R. Duke, R. Jones, B. Haley, E. Leslie, K. Paustian, and A. Swan, Net-Zero America: Potential Pathways, Infrastructure, and Impacts, interim report, Princeton University, Princeton, N.J., Dec. 15, 2020.

Roger Warburton: Nov. was the warmest Nov. yet recorded

From ecoRI News (ecori.org)

Stop me if you’ve heard this story before: Last month was the warmest ever.

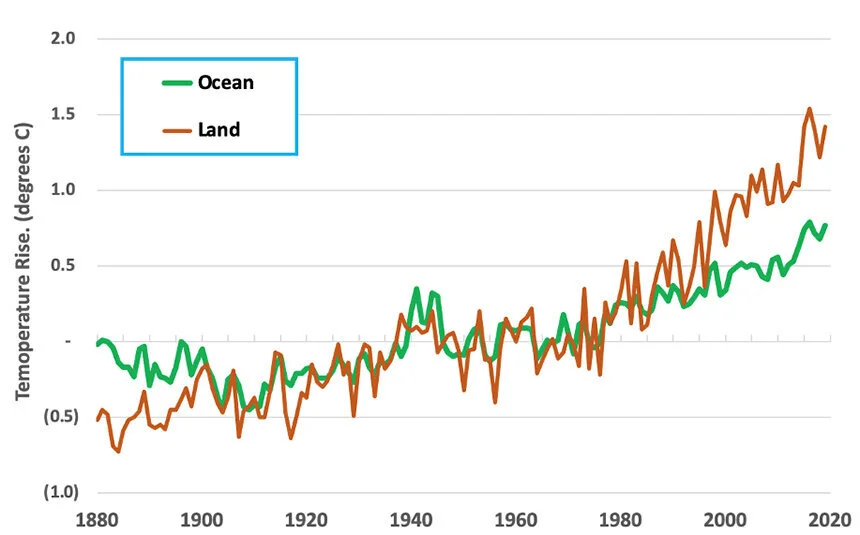

The latest global temperature data show that November 2020 was the warmest November ever recorded. The above figure shows the overall trend in global temperatures since 1880.

The red line for 2020 shows that average temperature for November was significantly above that of previous years. The significant rise in November’s temperature makes it very likely that 2020 will be the warmest year on record.

The figure below shows the average global November temperatures since 1880. The rise in November temperatures is quite substantial. The figure also shows that recent November temperature rises have been even more dramatic.

November mean surface air temperatures over land and ocean every decade since 1880. Data source: NASA GISTEMP. (Roger Warburton/ecoRI News)

In fact, the rise in November temperatures since 2015 is in line with a particularly disturbing trend: The latest data show that, since 2015, the warming trend is accelerating. The figure below shows the seriousness of the problem.

Global air temperatures over land and ocean. The yearly mean, blue, and the 5-year mean, red, have risen significantly above the gray trend line. Data source: NASA GISTEMP. (Roger Warburton/ecoRI News)

The gray line represents the steadily rising global temperature that was reasonably steady between 1970 and 2015. Since then, the temperature rise has accelerated. This is shown in the figure by the blue and red curves rising significantly above the gray trend line.

The gray trend line has often been used to predict long-term impacts of the future temperature rise. If the acceleration continues, many of the current estimates of the impacts of global warming will be seen as severely underestimated.

Roger Warburton, Ph.D., is a Newport resident. He can be reached at rdh.warburton@gmail.com.

References: GISTEMP Team, 2020: GISS Surface Temperature Analysis (GISTEMP), version 4. NASA Goddard Institute for Space Studies. Dataset accessed 20YY-MM-DD at https://data.giss.nasa.gov/gistemp/. Lenssen, N., G. Schmidt, J. Hansen, M. Menne, A. Persin, R. Ruedy, and D. Zyss, 2019: Improvements in the GISTEMP uncertainty model. J. Geophys. Res. Atmos., 124, no. 12, 6307-6326, doi:10.1029/2018JD029522.

An earlier pandemic New Year's

“New Year’s Baby 1919 (Dove Released from Cage)’’ (oil on canvas) by J. C. Leyendecker (1874-1951), for the Dec. 28, 1918 cover of The Saturday Evening Post. The picture ran only a few weeks after the end of World War I and during the horrific flu epidemic of that time.

(c) 2020 Image courtesy of the National Museum of American Illustration, Newport, RI, and the American Illustrators Gallery, New York, NY.

You can have her/him for free

“Love’s Lost Child at the Information Booth” (oil and pencil on board), by Thorton Utz (1914-1999), for the cover of the Dec. 20, 1958 Saturday Evening Post. It’s at The National Museum of American Illustration, Newport, R.I.

(c) 2020 Images Courtesy of the National Museum of American Illustration, Newport, RI, and the American Illustrators Gallery, New York, NY.

Not enough in Newport

“Hypotenuse", which was the Newport home of Gilded Age architect Richard Morris Hunt (1827-1895)

“To me Newport could never be a place charming by reason of its own charm. That it is a very pleasant place when it is full of people, and the people are in spirits and happy, I do not doubt. But then the visitors would bring, as far as I am concerned, the pleasantness with them”

~ Anthony Trollope (1815-1882), British novelist and civil servant

Famed Trinity Church in Newport, designed by Richard Munday and built in 1725-26. It hosts the oldest Episcopal parish (founded in 1698) in Rhode Island.

“I once knew an Episcopalian lady in Newport, Rhode Island, who asked me to design and build a doghouse for her Great Dane. The lady claimed to understand God and His Ways of Working perfectly. She could not understand why anyone should be puzzled about what had been or about what was going to be.

And yet, when I showed her a blueprint of the doghouse I proposed to build, she said to me, “I’m sorry, but I never could read one of those things.”

“Give it to your husband or your minister to pass on to God,” I said, “and, when God finds a minute, I’m sure he’ll explain this doghouse of mine in a way that even YOU can understand.”

~ Kurt Vonnegut, (1922-2007), American novelist, in Cat’s Cradle

Roger Warburton: Ocean damage increases in CO2 buildup as climate warms

January sea surface temperatures off southern New England have risen significantly since 1980.

— Roger Warburton/ecoRI News

From ecoRI News (ecori.org)

Living in Rhode Island, we are aware how the ocean rules our weather. What is less well known is that climate change is fundamentally altering the waters off our coast.

The image above shows how the January temperature of the ocean off New England has changed since 1980. For example, vast areas of dark blue — representing temperatures around 41-43 degrees Fahrenheit — have shrunk and are now a lighter blue, representing temperatures around 43-45 degrees.

The effects of a temperature rise in the ocean are significantly different from a temperature rise over land. We experience this difference when we walk across a sandy beach on a hot day. Exposed to the same sunlight, the sand burns our feet while the ocean warms gradually to the perfect temperature for a summer swim.

Rhode Island’s climate is moderated because the ocean takes longer than the land to heat up over the summer and longer to cool down during the fall.

The global impact of this effect is shown in the image below, which shows that, over recent decades, the continents have warmed much more rapidly than the oceans. The Earth’s land areas were 1.4 degrees Celsius (2.5 degrees Fahrenheit) warmer than the 20th-Century average, while the oceans were 0.8 degrees Celsius (1.4 degrees Fahrenheit) warmer.

Since 1880, the Earth’s land temperature has risen faster than the ocean temperature. “

— Roger Warburton/ecoRI News

Unfortunately, the ocean’s smaller temperature rise isn’t good news, because the oceans can store more than four times as much heat as the land.

Even though ocean temperatures have risen less than the land’s, it’s becoming clear that the impacts of climate change depend on a complex interaction between dry land and the warming ocean.

Ships and buoys have been recording sea surface temperatures for more than a century. International cooperation and sharing of data between nations has created a global database of sea surface temperatures going back to the middle of the 19th century.

In addition, modern satellites remotely measure many ocean characteristics over the entire extent of the Earth’s oceans. The data are now so accurate that it’s possible to detect the small temperature rise from ships’ propellers as they traverse the oceans.

The warming of both the land and the oceans is caused by rising levels of atmospheric carbon dioxide. When CO2 dissolves in the ocean, it forms carbonic acid, which in turn, breaks into hydrogen and bicarbonate ions. Clams, mussels, crabs, corals and other sea life rely on those carbonate ions to grow their shells.

In 2015, Mark Gibson, deputy chief of marine fisheries at the Rhode Island Department of Environmental Management, noted that ocean acidification is a “significant threat” to local fisheries.

In fact, a study published in 2015 found that the Ocean State’s shellfish populations are among the most vulnerable in the United States to the impacts of acidification.

In polar regions such as Alaska, the ocean water is relatively cold and can take up more CO2 than warmer tropical waters. As a result, polar waters are generally acidifying faster than those in other latitudes.

The water in warmer regions can’t hold as much CO2 and are releasing it into the atmosphere. Therefore, the acidification from carbon dioxide is damaging the oceans in both polar and equatorial regions.

Warming oceans are also changing the winds that whip up the ocean, resulting in upwells from deep waters that are nutrient-rich but also more acidic.

Normally, this infusion of nutrient-rich, cool, and acidic waters into the upper layers is beneficial to coastal ecosystems. But in regions with acidifying waters, the infusion of cooler deep waters amplifies the existing acidification.

In the tropics, rising temperatures are slowing down winds and reducing the exchange of carbon between deep waters and surface waters. As a result, tropical waters are becoming increasingly stratified and more saturated with carbon dioxide. Lower layers then have less oxygen, a process known as deoxygenation.

Warming ocean temperatures have also caused a rapid increase of toxic algal blooms. Toxic algae produce domoic acid, a dangerous neurotoxin, that builds up in the bodies of shellfish and poses a risk to human health.

In coastal areas, such as Rhode Island, temperature changes can favor one organism over another, causing populations of one species of bacteria, algae, or fish to thrive and others to decline.

The sum of all these impacts is damaging to the Rhode Island economy. The state’s shellfish populations are already among the most vulnerable in the United States to the impacts of a warmer ocean.

Roger Warburton, Ph.D., is an ecoRI News contributor and a Newport resident. He can be reached at rdh.warburton@gmail.com.

Figure 1 was generated using data from the Copernicus Climate Change and Atmosphere Monitoring Services (2020). The ERA5 dataset is produced by the European Space Agency SST Climate Change Initiative based on global daily sea surface temperature data from the Group for High Resolution Sea Surface Temperature and made available by the Copernicus Climate Data Store.

Figure 2 was generated using data from NOAA’s National Centers for Environmental information, Climate at a Glance: Global Time Series.

NED chats weekly on WADK's 'Talk of the Town'

On most Thursdays at 9:30 a.m., Robert Whitcomb from New England Diary and GoLocal24.com will chat with Bruce Newbury on Mr. Newbury’s Talk of the Town show on WADK-A.M. (Newport).

Listen to it via broadcast or wadk.com

“The Fireside Chat,’’ bronze sculpture by George Segal in Room Two of the Franklin Delano Roosevelt Memorial, Washington, D.C.. FDR ‘s fireside chats via radio were very popular among millions of Americans.

Glorious radio from 1941.

Expand the charm north in Newport

Of course not every neighborhood in Newport can look like this 18th Century section of “The City by the Sea.’’

From Robert Whitcomb’s “Digital Diary,’’ in GoLocal24.com

Newport is a fascinating little city, with its dramatic coastline, history, architecture and thick demographic/ethnic stew. And now there’s an interesting battle underway over how to redevelop its North End, a neighborhood with lots of low-income poor people and rather ugly cityscape. Visually, it sometimes seems that there’s “no real there there,’’ as Gertrude Stein said famously about Oakland, Calif.

I just hope that the final plan doesn’t result in making it look like a suburban-style shopping center/ office park with much of the space taken up by windswept parking lots. To show that it’s part of a city much of which is famous for its beauty, it should look like part of a city, with the density of one, and with green parks as well as a mix of new housing – resident-owned and rental -- stores and restaurants (with space for outdoor service) whose design speaks to the most attractive aesthetic traditions of the area. Newport is well known for its extremes of wealth and poverty. Thoughtful redevelopment of the North End can at least attempt to provide the unrich there with the opportunity to live in a neighborhood with the sort of built beauty than improves their socio-economic, as well as psychological, health, including by drawing in some of the visitors, and their wallets, who previously only went to the famous historic areas in the southern part of the city.

Village center on Block Island

I spent a day and night on Block Island last week: Gray skies, gray water, gray buildings and lots of red pants.

Dramatic dining in Newport

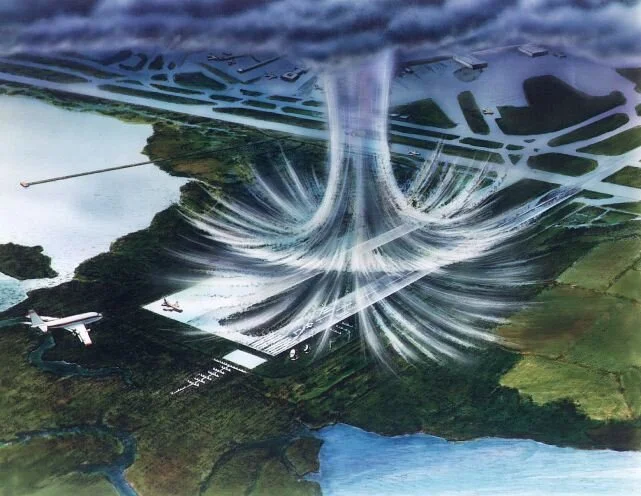

In a microburst, air moves in a downward motion until it hits ground level and then spreads outward in all directions. The wind regime in a microburst is opposite to that of a tornado.

From Robert Whitcomb’s “Digital Diary,’’ in GoLocal24.com

We witnessed a theatrical display of professionalism last Tuesday evening at the Reef Restaurant, on Newport Harbor, when out of not-very dark skies came a very brief but very violent storm of torrential rain and what seemed to be near-hurricane-force winds.

Most of the diners/drinkers, including us, were eating and drinking at the restaurant’s outside tables, with views of Newport Harbor and of giant yachts that evoked hedge funders and private-equity moguls, when the tempest hit. The four people in our party managed to get inside the restaurant ahead of most of the other guests; we were driven more by fear of being fried by lightning than getting wet. A few minutes before, our tall young waiter had promised that the storm, which we could see moving in from the west, wouldn’t bother us. One of our little group, a pilot, later explained that it was a microburst.

It was quite a scene as umbrellas, deck chairs, tables and potted palms went over.

What was most impressive, besides the drama of the storm itself, was how the waiters so calmly managed to get people quickly set up at tables inside, though they hadn’t time to rescue the food on the tables outside. Of course, social distancing was, er, incomplete in the brief chaos, and many who had fled inside had left their masks in the rain, some of which blew away and all of which were soaked.

Still, most of the guests seemed to enjoy the mayhem. I wonder how many got replacement meals and drinks.

xxx

The National Hurricane Center knows how to force fear. In alerting people in the northwest Gulf Coast to the menace of Hurricane Laura, it spoke of an “unsurvivable storm surge.’’

Annie Sherman: R.I. coastal properties at risk as waters rise

Historic house in Newport’s flood-threatened Point neighborhood

From ecoRI News (ecori.org)

NEWPORT, R.I.

On her first day of work at the Newport Restoration Foundation, in 2015, Kelsey Mullen arrived late. The house in which she was living had flooded again, and water on the street rimmed her car’s tires.

The Bridge Street home in the city’s historic Point neighborhood is at a confluence of water sources near city storm drains and Newport Harbor, so its stone foundation provides little barrier to storms or high tides. The ground is often saturated and slopes gently toward the house, so water has nowhere to go but inside and all around. The basement perpetually smelled like the sea, Mullen said, while sump pumps and dehumidifiers kept busy.

Built in 1725 by famed furniture maker Christopher Townsend, 74 Bridge St. sits just 4 feet above sea level. Luckily, it hasn’t sustained permanent damage, but the home is a stunning reminder of what could happen to entire neighborhoods if action isn’t taken to protect them from the damaging effects of increased water.

The Environmental Protection Agency reports seas have risen 10 inches since 1880, and they are projected to swell as much as 3 feet during the next 50 years. Coupled with flooding from chronic rain events, coastal houses like this little red Colonial and historic business districts from Narragansett to Westerly and Warwick to Bristol will be underwater.

“This is the canary in the coal mine, where rising water is impacting this house and we will see impacts in other houses,” said Mullen, now the director of education at the Providence Preservation Society. “With this issue, there are no experts, there is no benchmark. If you’re waiting for an official sanctioned recommendation, it’ll be too late, and there will be loss along the way.”

Since seaports and coastal communities were settled first historically, there are billions of dollars of valuable resources in harm’s way statewide.

“Back in 2007, there was the feeling that, ‘Let’s not worry about it,’” said Wakefield-based historic-preservation expert and community planner Richard Youngken. “Now everyone is concerned because it’s getting worse.”

Guidance from the Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA) and the National Park Service provides approximate courses of action, while urgent pressure to find a solution forces cities and towns, preservationists and engineers, individual organizations, and homeowners to assess risk, then develop and execute a specialized strategy on their own.

This triggers inconsistent approaches, because what works for one house or municipality, might not work for another, said Arnold Robinson, historic preservationist and regional planning director for Fuss & O’Neill engineers in Providence.

“Flooding varies in different hydrologies and geographies, so what happens in Louisiana is different than Vermont, and how they deal with it is different. So that leaves us preservationists to figure it out, and share solutions with each other,” Robinson said. “There is a lack of funding for this adaptation, too. We are not investing in making historic resources more resilient. And if you look at the economy of New England states, history is our economic engine.”

A ‘future archipelago’

Initiatives in Newport and North Kingstown, most notably in its village of Wickford, which are at the Ocean State’s risk epicenters among its 21 coastal municipalities, show progress. These two coastal communities alone boast 842 historic structures of 1,971 statewide, wrote Youngken in his 2015 report Historic Coastal Communities and Flood Hazard: A Preliminary Evaluation of Impacts to Historic Properties.

The number of National Register‐listed or eligible resources in Rhode Island’s coastal and estuarine flood zones, as mapped by FEMA. (Youngken Associates)

With more than $432 million of historic properties within FEMA flood zones, he reported, Newport has the most to lose. A lion’s share of the City by the Sea’s historic district and tourism cash cow could be swallowed by water, including original Colonial buildings on Bowen’s Wharf, Market Square, the historic Brick Market and lower Washington Square, Long Wharf, and The Point, and most of the Fifth Ward and Ocean Drive, according to Youngken.

“Imagine flooding all along Thames Street and everything west of Queen Anne’s Square,” Youngken said. “With sea-level rise, all of that comes into jeopardy, so you lose a big portion of the city. The same is true of Wickford. Rhode Island would become a series of islands — our future archipelago.”

Hoping to stem the deeper existential forces of climate change-induced flooding and sea-level rise, Newport this year issued the state’s first guidance plan for residents to elevate their historic properties. These voluntary guidelines clarify what the city will examine with homeowners’ elevation requests, as well as provide additional advice for materials, siting, options for building accessibility, decreasing hardscapes, and increasing green space and drainage to eliminate excess water in overburdened municipal systems.

“Resiliency to climate change, and specifically the threat posed by rising sea levels, is a fundamental component to the city’s long-term historic-preservation goals, and these guidelines speak to that,” said Newport’s historic-preservation planner Helen Johnson. “For several years, we’ve been exploring how rising sea levels are projected to impact some of our most historically significant and environmentally sensitive neighborhoods. And while we can’t control the tides, we can influence how we respond as a community.”

In some cases, elevation may not be ideal. It’s expensive, costing between $40,000 to $250,000, and myriad limitations could stymie the most steadfast preservationist. Many houses on The Point, for instance, are situated on the front property line, with their front steps on the sidewalk, so building access is essential to consider, Johnson said, as is drainage and so much else.

“Some homeowners can move the house back, others cannot, so you have to get creative,” she said. “It also impacts the historic streetscape. Some preservationists argue that this approach defeats the purpose, as does relocating the house to drier ground.”

City officials, including the Historic District Commission that drafted the guidelines and will review all future elevation applications, said they recognize that for homes in some of Newport’s more vulnerable areas, elevation is the best route to preservation. The Point has set the elevation precedent during the past century, with many houses already raised since the hurricane of 1938, Johnson said.

The new guidelines complement a series of flood gates buried at vulnerable spots in the city, including the Wellington Avenue and The Point neighborhoods. Another is planned for King Park. The gates act as tourniquets to stop salt water from rushing in from the harbor and to allow stormwater to drain from higher areas.

Though flooding still occurs, especially at high and king tides, Johnson noted that they quickly proved to be a viable option to mitigate flooding.

“But these types of infrastructures can only get us so far,” she said. “The other side is elevating buildings and preparing our aboveground infrastructure as well. But depending on a house’s location in the flood zone, it might have to go up really high. So, when is it not feasible to elevate it, and if you move it, where does it go and does it lose its historic significance? We don’t have those answers, and don’t touch on that in these guidelines, because we wanted to focus on what was achievable.”

On ‘verge of disasters’

Nonprofits like the Preservation Society of Newport County (PSNC) and the Newport Restoration Foundation (NRF) are paying attention to those unanswered questions.

PSNC’s 266-year-old Hunter House is perched a few meters from Newport Harbor, its basement floods regularly, and its Bannister’s Wharf store frequently sees water just inches from its front door, according to the organization’s executive director, Trudy Coxe. It hasn’t lost anything yet, she said, but its staff has become adept at relocating both buildings’ contents while they consider contingency solutions, including elevation and amphibious technology.

“Hunter House was even built to endure flooding, so it’s set back slightly and has a small plot of land. But that house is at risk, which is true for a lot of houses along Washington Street,” Coxe said. “I don’t think any state in America is doing enough. One of the things that gets in the way of doing more is that we don’t know what we should be doing. The solutions are incredibly expensive. Plus, people think they can pass it to the next generation, or that someone will come along and wave a magic wand and it will all go away.

“But predictions are pointing to it getting rougher out there. We are on the verge of disasters.”

The NRF is equally concerned. It has preserved and restored more than 80 homes from the 18th and early 19th centuries, 25 of which are in The Point, including 74 Bridge St. Though it hasn’t adapted or elevated its houses to accommodate excessive water, that’s not to say the organization won’t, according to executive director Mark Thompson.

Though the NRF sold 74 Bridge St. in early July, Thompson said he suspects that it’s a candidate for elevation with its new owners’ rejuvenation plan.

“A lot of people think that The Point is the focal point of the climate-change issue in Newport, but we are not just interested in our houses, we are interested in Newport, because if we save 25 houses, and nobody else is able to do that, then there is no point in it,” Thompson said. “Cities around the world say infrastructure should be erected, like gating systems, and elevating or relocating houses to preserve the integrity, but how high do you raise it to be effective? Our goal is to save the houses where they are, and that we save them the right way.”

NRF’s interest in that signature property inspired it to launch a national conference where experts discussed these issues and possible solutions. Its inaugural Keeping History Above Water event in Newport in 2016 became a huge success, said Mullen, who was then NRF’s public-program manager. Since then, it has spread to other coastal communities, including St. Augustine, Fla., Annapolis, Md., and Palo Alto, Calif. The conference is scheduled to be held in Charleston, S.C., next year.

J. Paul Loether, executive director of Rhode Island’s Historical Preservation & Heritage Commission, also is trying to create an intelligence clearinghouse to help municipalities, homeowners, and nonprofits streamline strategies. As experts in knowing what properties are significant across the state, the Providence-based commission wants to secure funding and political influence to amplify preservation and to identify the highest risk areas and better equip municipal planners.

“Newport’s solution will work for them as a city, but we need to be more strategic as a state,” Loether said. “It doesn’t take much to visualize Main Street in Wickford being underwater. So, we want to give them the best information we can. But there is no easy answer. It raises philosophical issues, financial issues; where is the tipping point? I have seen houses in Connecticut raised 12 feet and it looks like Orson Welles’ ‘War of the Worlds.’ But others you can’t even tell.

“It’s not driven by preservation in many cases, it’s driven by the rising cost of FEMA flood insurance. If you’re dealing with a single structure, it’s one thing, but the whole neighborhood? Are you going to raise the street? Then you have to wonder, are we preserving history or preserving the property? Then the bigger issue is, do you really have a historic district?”

From the Ocean State to the Golden State, there are more questions than answers, which is precisely why the approach is scattershot. But as storms become more frequent and intense and nuisance flooding becomes more routine necessity will drive activity. Though no residents in Newport have received elevation approval yet, Johnson, the city’s historic preservation planner, remains optimistic that this is the way forward.

“We want to get these communities together to learn from what we’re doing here in Newport and see if we can help other municipalities develop their own guidelines,” she said. “We are such a small state but we are so diverse in our building stock and municipal resources, so we need to discuss the impacts and things we can do to tackle sea-level rise and floodwater.”

In the meantime, there are tough truths we must face, Mullen said.

“In terms of cultural heritage, there are only a few possible reactions: you either raise up structures; you relocate structures; or you retreat,” she said. “And ultimately, maybe 100 years, retreat is the only predictable outcome. We’re not seeing reversal in climate trends, and climate scientists say the projections are too conservative. So, if we know the conditions are unlikely to change, we have to change the way we live, and make proactive decisions now about what we’re willing to lose and what we’d like to keep.”

Annie Sherman is a freelance journalist based in Newport covering the environment, food, local business, and travel in the Ocean State and the rest of New England. She is the former editor of Newport Life magazine, and author of Legendary Locals of Newport.

Invasive little pet turtles

Red-Eared Sliders

From ecoRI News (ecori.org)

They are the most popular pet turtle in the United States and available at pet shops around the world, but because Red-Eared Sliders live for about 30 years, they are often released where they don’t belong after pet owners tire of them. As a result, they are considered one of the world’s 100 most invasive species by the International Union for the Conservation of Nature.

Southern New England isn’t immune to the problems they cause.

“I hear the same story again and again,” said herpetologist Scott Buchanan, a wildlife biologist for the Rhode Island Department of Environmental Management. “‘We bought this turtle for a few dollars when Johnny was 8, he had it for 10 years and now he’s going to college, so we put it in a local pond.’ That’s been the story for hundreds and thousands of kids in recent decades.”

Red-Eared Sliders are native to the Southeast and south-central United States and northern Mexico, where they are commonly found in a variety of ponds and wetlands. Buchanan said they are tolerant of human disturbance and tolerant of pollution, and they are dietary generalists, so they can live almost anywhere. And they do. They breed throughout much of Australia as a result of pets being released, and in Southeast Asia they are raised as an agricultural crop and have displaced numerous native species. In the Northeast, they live in the same habitat as Eastern Painted Turtles, one of the area’s most common species, but they grow about 50 percent larger. Numerous studies suggest that sliders outcompete native turtles for food, nesting, and basking sites.

Despite concerns about their impact on native turtle populations, red-eared sliders are still legal to buy in Rhode Island and most of the United States, though Buchanan said that in the Ocean State they may only be sold by a licensed pet dealer and can’t be transported across state lines. Those who buy a slider must keep it indoors and must never release it into the wild, including into a private pond.

“But people often aren’t aware of the regulations, or they don’t bother to look at them, or they just don’t follow them,” Buchanan said. “We see lots of evidence of sliders, especially in parts of the state where there are lots of people. The abundance of Red-Eared Sliders in Rhode Island is tied to human population density, which means mostly Providence and the surrounding communities. But I’ve also found them in Newport and Narragansett and elsewhere.”

Sliders are especially common in the ponds at Roger Williams Park, in Providence, and in the Blackstone River.

While conducting research for his doctorate at the University of Rhode Island from 2013 to 2016, Buchanan surveyed ponds throughout the state looking for spotted turtles, a species of conservation concern in the region. During his research, he also documented other turtle species, including many red-eared sliders.

“The good news was that while spotted turtles can occupy the same habitat as red-eared sliders, I found a greater probability of occupancy by spotted turtles at the opposite end of the human density spectrum as I found sliders,” he said. “Spotted turtles tend to occur where human population density is low, so at least at this moment in time, we would not expect red-eared sliders to be directly competing with populations of spotted turtles.”

Nonetheless, Buchanan advocates what he calls a “containment policy” to keep the sliders from expanding their range in the state.

“It’s mostly about public education,” he said. “We want to make sure people know not to release them in their local wetlands. If we found sliders in an important conservation area — Arcadia, for example — we might consider removing them, though we’re not doing that now.

“They’re well-established in Rhode Island now, so the thought of eradicating them does not seem like a feasible management solution. We just have to live with them, but we also have to try to minimize their spread and colonization of new wetlands.”

No other non-native turtle from the pet trade besides the Red-Eared Slider has been found to be a common sight in the wild in Rhode Island, though Buchanan said he recently had a report of a Russian tortoise — another popular pet — that was discovered wandering around Coventry.

For those who want to get rid of a pet Red-Eared Slider, Buchanan doesn’t offer any easy alternatives.

“You’ve got to be committed to housing that turtle for 30 or 40 years until it dies,” he said. “That’s why this is such a problematic issue. It’s easy to buy a teeny turtle for ten bucks and think it’s no big deal, but that animal is going to live for a long time. When you purchase it, you have to be responsible for it for the rest of the turtle’s life.”

Rhode Island resident and author Todd McLeish runs a wildlife blog.

Three steps in passing them

“The Fairman Rogers Four-in-Hand,’’ by Thomas Eakins, (1880)

“Between five o’clock and sunset, society drove up and down Bellevue Avenue and Ocean Drive….The two-way procession passed and repassed. It was said: The first time you met a friend, you make a ceremonious bow; the second time, you smiled; the third you look away.’’

— Bertram Lippincott, on Newport, R.I., in the early 20th Century, in Indians, Privateers and High Society (1961)

The future summer resort

By 1890, the extension of frequent rail service to the Cape was turning the peninsula into a famous place to go in the summer. Many of the natives were ambivalent about this development.

“The time must come when this coast (Cape Cod) will be a place of resort for those New-Englanders who really wish to visit the sea-side. At present it is wholly unknown to the fashionable world, and probably it will never be agreeable to them. If it is merely a ten-pin alley, or a circular railway, or an ocean of mint-julep, that the visitor is in search of, — if he thinks more of the wine than the brine, as I suspect some do at Newport, — I trust that for a long time he will be disappointed here. But this shore will never be more attractive than it is now.”

― Henry David Thoreau, (1817-62) in Cape Cod

Global ambitions

“June Graduate” (1920, oil on canvas), by J.C. Leyendecker (1874-1951), Saturday Evening Post’s June 5, 1920 cover, at the National Museum of American Illustration, Newport, used with museum’s permission.