Llewellyn King: Censorship isn’t the solution to the ills spread by social media

Censorship came to British America when the governor of Plymouth, William Bradford, learned in 1629 that Thomas Morton, founder of the relaxed settlement of Merrymount (now part of Quincy), had '‘composed sundry rhymes and verses, some tending to lasciviousness.’’ The solution was to send a military expedition to arrest him (above) and stop the good times at Merrymount.

This society, founded in 1879 and dissolved in 1975, pushed to censor material it saw as immoral.

WEST WARWICK, R.I.

Technology is tampering with freedom of speech, and we don’t know what to do about it. At issue are the global platforms Facebook, Twitter and Instagram and the disturbing propaganda, disinformation and lies propagated on them.

The inclination, on the left and the right, is to censor. It is a terrible solution, more toxic and damaging to the body politic than the disease.

The left would like to shut down Fox Cable News and its principal commentator, Tucker Carlson. The right would like to have Twitter sold, presumably to Elon Musk, so that it stops blocking tweets from the right, notably those from former President Trump.

How our society and others deal with the downside of social media — racial incitement, disinformation, mendacity and opinions that are offensive to a minority, whether that is the disabled or an ethnic group — is a work in progress. The instinct is to shut them down, shut them up. The tool — that old monster solution — is censorship.

The first trouble with censorship is that it has to define what is to be eradicated. Take hate speech. The British Parliament is struggling with a bill to limit it. The social networks seek to exclude it, and there are U.S. laws against crimes inspired by it.

How do you define it, hate speech? When is it fair comment? When is it satire? When is it truth taken as hate?

I say if you can untie that knot, go ahead and censor. But I also know you can’t untie it without savaging free speech, doing violence to the First Amendment, arresting creativity and hobbling humor.

The censor is often as much clothed in moral raiment as in political garb. Take Thomas Bowdler and his sister, Henrietta, who in 1807 published an expurgated version of the works of Shakespeare. Henrietta did most of the work on the first 20 plays, later Thomas finished all 36. They expunged sex, blasphemy and double entendre. Thomas was an admired scholar, not a crackpot, although that might be today’s judgment.

Oddly, the Bowdlers are credited with increasing the readership of Shakespeare. People reached for the forbidden fruit; they always do.

Likewise, many a novel would have avoided success if it hadn’t been serially banned, like D.H. Lawrence’s Lady Chatterley’s Lover. The moral censorship of movies by the Hays Office, starting in 1934, didn’t save the audiences from moral turpitude. It just led to bad movies.

The censors often begin with specific words; words, which it can be argued, represent offense to some group or some social standing. So specific words become demonized — whether it is the naming of a sports team or a colloquial word for sex, the urge to censor them is strong.

Jokes, like the English ones about the Welsh or the Scots ones about the English, became victim to a newly minted sensitivity, where political activists sell the idea that the joked about are victims. The only victim is levity, to my mind.

When you start down this slope there is no apparent end. Euphemisms take over from plain speech, and we live in a society in which the use of the wrong word can suggest that you are not fit for public office or to teach. Areas around ethnicity and sexual orientation are particularly fraught.

Until the 1960s and the civil rights movement, newspapers de facto censored people of color: They ignored them — a particularly egregious kind of censorship. At The Washington Daily News, where I once worked, a now defunct but lively evening newspaper in the nation’s capital, some of us once ransacked the library for photos of Blacks. There were none. From its founding in 1927 until the civil rights movement took off, the newspaper simply hadn’t published news of that community in a city that had a burgeoning African-American population.

That was collective censorship as pernicious as the kind that both political extremes would now like to impose on speech.

Alas, censorship — banning someone else’s speech — isn’t going to redress the issue of the rights of those maligned or lied to or excluded from social media. In print and traditional broadcasting, libel has been the last defense.

Libel laws are clearly inadequate and puny against the enormity of social media, but they are a place to begin. A new reality must, and will in time, get new mechanisms to contend with it.

One of those mechanisms shouldn’t be censorship. It is always the first tool of dictatorship but should be an anathema in democracies. For example, it is an open issue as to whether Russian President Vladimir Putin would have been able to invade Ukraine if he hadn’t first censored the Russian media.

On Twitter: @llewellynking2

Llewellyn King is executive producer and host of White House Chronicle, on PBS. He’s based in Rhode Island and Washington, D.C.

Llewellyn King: For society’s sake, newspapers, whose work is looted by tech firms, deserve a reprieve

WEST WARWICK, R.I.

Newspapers are on death row. The once great provincial newspapers of this country, indeed of many countries, often look like pamphlets. Others have already been executed by the market.

The cause is simple enough: Disrupting technology in the form of the Internet has lured away most of their advertising revenue. To make up the shortfall, publishers have been forced to push up the cover price to astronomical highs, driving away readers.

One city newspaper used to sell 200,000 copies, but now sells less than 30,000 copies. I just bought said paper’s Sunday edition for $5. Newspapering is my lifelong trade and I might be expected to shell out that much for a single copy, but I wouldn’t expect it of the public to pay that — especially for a product that is a sliver of what it once was.

New media are taking on some of the role of the newspapers, but it isn’t the same. Traditionally, newspapers have had the time and other resources to do the job properly; to detach reporters to dig into the murky, or to demystify the complicated; to operate foreign bureaus; and to send writers to the ends of the earth. Also, they have had the space to publish the result.

More, newspapers have had something that radio, television and the Internet outlets haven’t had: durability.

I have a stake in radio and television, yet I still marvel at how newspaper stories endure; how long-lived newspaper coverage is compared with the other forms of media.

I get inquiries about what I wrote years ago. Someone will ask, for example, “Do you remember what you wrote in 1980 about oil supply?”

Newspaper coverage lasts. Nobody has ever asked me about something I said on radio or television more than a few weeks after the broadcast.

I was taken aback when, while I was testifying before the Senate Foreign Relations Committee decades ago, a senator asked me about an article I had written years earlier and forgotten. But he hadn’t and had a copy handy.

There is authority in the written word thay doesn’t extend to the broadcast word, and maybe not to the virtual word on the Internet in promising new forms of media like Axios.

If publishing were just another business – and it is a business — and it had reached the end of the line, like the telegram, I would say, “Out with the old and in with the new.” But when it comes to newspapers, it has yet to be proven that the new is doing the job once done by the old or if it can; if it can achieve durability and write the first page of history.

Since the first broadcasts, newspapers have been the feedstock of radio and television, whether in a small town or in a great metropolis. Television and radio have fed off the work of newspapers. Only occasionally is the flow reversed.

The Economist magazine asks whether Russians would have supported President Vladimir Putin’s invasion of Ukraine if they had had a free media and could have known what was going on; or whether the spread of COVID in China would have been so complete if free media had reported on it early, in the first throes of the pandemic?

The plight of the newspapers should be especially concerning at a time when we see democracy wobbling in many countries, and there are those who would shove it off-kilter even in the United States.

There are no easy ways to subsidize newspapers without taking away their independence and turning them into captive organs. Only one springs to mind, and that is the subsidy that the British press and wire services enjoyed for decades. It was a special, reduced cable rate for transmitting news, known as Commonwealth Cable Rate. It was a subsidy but a hands-off one.

Commonwealth Cable Rate was so effective that all American publications found ways to use it and enjoy the subsidy.

United Press International created a subsidiary, British United Press, which flowed huge volumes of cable traffic through London.

Time Inc. had a system in which their cable traffic was channeled through Montreal to take advantage of the exceptionally low, special rates in the British Commonwealth.

That is the kind of subsidy that newspapers might need. Of course, best of all, would be for the mighty tech companies to pay for the news they purloin and distribute; for the aggregators to respect the copyrights of the creators of the material they flash around the globe. That alone might save the newspapers, our endangered guardians.

Llewellyn King is executive producer and host of White House Chronicle, on PBS. His email is llewellynking1@gmail.com and he’s based in Rhode Island and Washington, D.C.

Llewellyn King: The threat of nuclear war and the license it has given Russia’s dictator

WEST WARWICK, R.I.

History isn’t short of people to blame. You could say of the present world crisis that it was former President Obama’s fault for not getting tougher with Russian President Putin in Syria. You could blame former President Trump for giving Putin a sense of entitlement and for undermining NATO, seeing it as a financial play. You could blame former German Chancellor Angela Merkel for encouraging Russian gas imports, shutting out the nuclear- energy option.

You could, of course, blame President Biden for explicitly telling Putin, and the world, what the United States wouldn’t do if he invaded Ukraine. And you could blame Biden and NATO for dribbling vital military aid to Ukraine over the first devastating weeks of the Russian invasion.

If you want to continue, you could blame the world’s military strategists for believing that Russia, after the fall of communism, had changed. You could, perhaps, blame NATO itself, for expanding its reach to the former Soviet republics of Estonia, Lithuania and Latvia.

But Putin is unequivocally the one to blame. The dictator is the one who wants to remake Russia in the image of the imperial tsars. It is a flawed scheme but a real one.

As the world grapples with the reality of Putin, the past informs but it doesn’t instruct.

If NATO were to engage Russia with conventional forces, it would triumph. That is one lesson of Ukraine. Russian military forces are woefully inefficient, even incompetent.

Would it were that simple.

The beast in the room, the feared monster, the threat that hangs over the whole world is nuclear war. It is the clear-and-present danger. It shapes our handling of Russia and will shape our response to China, if and when it invades Taiwan.

Nuclear-war avoidance is again dominating the world in ways we had nearly forgotten.

Will Russia, a caged, fierce bear, resort to nuclear, and how much nuclear to what effect against which targets?

The United States and the Soviet Union reached a modus vivendi: mutual assured destruction (MAD), which kept the peace even as nuclear armaments proliferated and stockpiles grew exponentially. Is that still the option? Is MAD -- so long after the collapse of the Soviet Union -- still the underlying realpolitik, the restraining factor between nuclear powers?

Does that mean that anyone with nuclear weapons can wage conventional warfare in the belief that they won’t face NATO or any other serious restraining military action because they can unleash terrifying global destruction?

Or is there, as some believe, the prospect of limited nuclear engagement, using area tactical nuclear weapons? This has never been tested.

There hasn’t been a limited nuclear ground war. Could it be contained? Should it be contemplated outside the deeper reaches of the defense establishment?

But it is what keeps the leaders of Europe, the United States and Canada awake nights. If you favor limited nuclear war, just look to the effects of a nuclear disaster, Chernobyl, and start multiplying.

It is the unthinkable scenario that must be thought about. It is the reality which holds back NATO and makes the West a spectator to the carnage in Ukraine.

Russia isn’t a rich country except in some natural resources. It has a large but poorly trained and equipped military. But it bristles with nuclear weapons aimed at North American and European cities. Its ability to threaten us with nuclear horror changes the balance between nations: an indelible change to future foreign policy.

In the short term, when contemplating the return of MAD in international relations, the question is: How mad – as in insane -- is Putin, and how ready is Biden?

The pieces on the world chess board have moved and they won’t be moved back. The intelligentsia has yet to grasp the extent to which Ukraine has changed the world – and made it a more dangerous place. They need to catch up fast.

Llewellyn King is executive producer and host of White House Chronicle, on PBS. His email is llewellynking1@gmail.com and he’s based in Rhode Island and Washington, D.C

Llewellyn King: The new normal will take time, not politics

WEST WARWICK, R.I.

Loud detonations are going off in the economy. When the debris settles, new realities will emerge. We won’t return to the status quo ante, although that is what politicians like to promise.

After great cataclysmic events — wars, natural disasters or the impact of new technologies — we need to acknowledge the realities and find the opportunities.

The inflation that is shaking the world is the inflammation that arises as markets seek equilibrium — as markets always do.

The greatest disrupter has been the COVID-19 pandemic, and the ramifications of how it has reshaped economies and societies are still evolving. For example, will we need as much office space as we did pre-pandemic? Is the delivery revolution the new normal?

Russia’s war in Ukraine has added to the pandemic-caused changes before they have fully played out. They, in turn, were playing out against the larger imperatives of climate change, and the sweeping adjustments that are underway to head off climate disaster.

Some political actions have exacerbated the turbulence of the economic situation, but they aren’t the root causes, just additional economic inflammation. These include former president Donald Trump’s tariffs and President Biden’s mindless moves against pipelines, followed by attempts to lower gasoline prices, or wean us from natural gas while supplying more natural gas to Europe.

In the energy crisis (read shortage) of the 1970s, I invited Norman Macrae, the late, great deputy editor of The Economist, to give a speech at the annual meeting of The Energy Daily, which I had created in 1973 — and which was then a kind of bible to those interested in energy and the crisis. Macrae, who had a profound influence in making The Economist a power in world thinking, shared a simple economic verity with the audience: “Llewellyn has invited me here to discuss the energy crisis. That is simple: the consumption will fall, and the supply will increase. Poof! End of crisis. Now, can we talk about something interesting?”

Of the many, many experts I have brought to podiums around the world, never has one been as warmly received as Macrae. Not only did the audience stand and applaud, but many also climbed on their chairs and applauded. I’m not sure Washington’s venerable Shoreham Hotel had ever seen anything like that, at least not at a business conference.

In today’s chaotic situation with political accusations clashing with supply realities, the temptation is to find a political fix while the markets seek out the new balance. Politicians want to be seen to do something, no matter what, and before it has been established what needs to be done.

An example of this was Biden increasing the allowed amount of ethanol derived from corn and added to gasoline. It is so small an addition that it won’t affect the price at the pump, but it might affect the price of meat at the supermarket. Corn is important in raising cattle and feeding large parts of the world.

There is a global grain crisis as a result of Russia’s war in Ukraine, which is a huge grain producer. Parts of the world, especially Africa, face starvation. The last thing that is needed is to sop up American grain production by burning it as gasoline.

We are, in the United States, gradually moving from fossil fuels to renewables, but this is going to move our dependence offshore, and has the chance of creating new cartels in precious metals and minerals.

Essential to this move is the lithium-ion battery, the heart of electric vehicles and battery storage for renewables, and its tenuous supply chain. Lithium has increased in price nearly 500 percent in one year. It is so in demand that Elon Musk has suggested he might get into the lithium mining business.

But lithium isn’t the only key material coming from often unstable countries: There is cobalt, mostly supplied from the Democratic Republic of the Congo; nickel, mostly sourced in Indonesia; and copper, where supply comes primarily from Chile.

Across the board, supplies will increase, and demand will decline. Equilibrium will arrive, but vulnerability won’t be eliminated. That is an emerging supply chain constant as the economy shifts to the new normal.

The aftershocks of the pandemic and Russia’s war in Ukraine will be felt for a long time — and endured as inflation.

On Twitter: @llewellynking2

Llewellyn King is executive producer and host of White House Chronicle, on PBS. He’s based in Rhode Island and Washington, D.C.

Llewellyn King: Trying to spread the innovation culture to old businesses

100, 300, and 500 Technology Square, in Cambridge, Mass., as seen from Main Street. The neighborhood has been the site of many technological breakthroughs for decades.

WEST WARWICK, R.I.

Microsoft is buying, subject to regulatory approval, Activision Blizzard for $69 billion. The Internet of Things is white-hot and likely to remain so.

If you want to whistle at that humongous sum for a company that makes games, you may have to add many octaves to the known musical scale.

Yes, high-tech is chasing trivia. The imperative at work here is if you don’t get your latest game into the market, someone else will. The threshold of entry is low and the rewards are astronomical.

If you are talking innovation and creativity, you are talking the Internet. That means that whole areas of society aren’t progressing as fast as they might and should. There is asymmetry.

The Internet firmament is driven not by market demand, but by a business dynamic that exists in the world of internet entrepreneurism: Innovate and create because the internet can create great wealth — and take it away, too.

Most non-Internet companies — and I talk to a fair number of CEOs — say that they are innovative and that they are innovation-driven but, in fact, they aren’t. Most companies don’t need to innovate the way the internet giants do. The metaverse is demonstrably an unstable place.

Most companies are looking for stability, for a plateau where they can manage what has been created while adding to it cautiously, often by acquisition. They confuse innovation with evolutionary improvement. The last thing they want is the kind of destructive innovation that characterizes Silicon Valley.

The febrile need to innovate in the Internet world is unique to that world. This because internet companies are all on a treacherous slope; failure can come as fast as success. Remember MySpace, Nokia, Palm, and Wang?

The Internet is global, and it is intrinsically favorable to monopoly. In the internet world, first past the post takes the prize money — all of it.

When you have market caps that value a company at $1 trillion, and all of that is dependent on the next innovation not overtaking you, you are going to throw money and talent at innovation because the alternative is known. Whenever possible, you are going to buy up your competition, hence the Microsoft purchase.

With all of the money, all of the glamor, all of the talent, there also is fear that some kid in a garage somewhere will invent the next big thing.

I submit that for the non-Internet world the business dynamic is very different. Most CEOs of public companies, snug in their C-suites and buttressed by huge salaries, are seeking a quiet place; a plateau where profits grow but there is some business serenity. For example, Boeing doesn’t want new airframes, it wants upgraded models.

They won’t admit to it, but many businesses long to be rent takers (known collectively as rentiers). They want a steady income with small risk.

Unfortunately, the business culture, including that spawned in business schools, aims to channel ambition into the rent-taking model. We have a business culture where ambition is channeled toward climbing to the top of the established order, not creating a new order.

There are many excellent minds managing established companies, often established many decades earlier, but there are few who yearn to create something wholly new.

The great names of management are many, but the great names of true innovation are few. Almost always, they have to break away from the established to create the new, to alter the world.

My friend Morgan O’Brien, the co-creator of Nextel, and now the executive chairman of the pioneering wireless company Anterix, is that kind of innovator who saw new horizons and went for them.

Today’s standout inventor is Elon Musk. He began as an Internet whiz with PayPal and has blazed the innovation trail like no other since Thomas Edison, more than a century earlier. He has changed the world underground with new concepts of subways, changed surface transportation by going electric, and changed space with his rockets.

Thirty years ago, I wrote that the weakness of U.S. companies is that they are happy to make silent movies when the talkies have been invented. Today, the established auto manufacturers are hell-bent to make electric pickup trucks now that new entrepreneurs are in the truck market with electric trucks. They never wanted to abandon the internal-combustion engine, just improve it a little at a time.

If the dynamic of the Internet and its constant innovation is missing in most American businesses, it needs to be grafted onto the business body politic. Must the Internet be behind every innovation of consequence? Ride-sharing and additive manufacturing (3D printing) are all computer-driven — software at work.

The challenge for the business culture is to harness ambition – it is never in short supply — and point it not toward the greasy pole of promotion, but toward the firmament of innovation.

On Twitter: @llewellynking2

Llewellyn King is executive producer and host of White House Chronicle, on PBS. He’s based in Rhode Island and Washington, D.C.

White House Chronicle

Llewellyn King: Utilities urgently need to add transmission

In Seekonk, Mass., during the height of the Jan. 29 blizzard. Many people in southeastern Massachusetts lost power in the storm, in which winds gusted to hurricane force.

Logo of Independent System Operator, which oversees the region’s electric grid.

WEST WARWICK, R.I.

It has become second nature. You hear that bad weather is coming and rush to the store to stock up on bottled water and canned and other non-perishable foods. You check your flashlight batteries.

For a few days, we are all survivalists. Why? Because we are resigned to the idea that bad weather equates with a loss of electrical power.

What happens is the fortunate have emergency generators hooked up to their freestanding houses. The rest of us just hope for the best, but with real fear of days without heat.

It happened most severely in Texas in February 2021; during Winter Storm Uri, which lasted five days, 250 people died. Recently, during the Blizzard of 2022, on Jan. 28-29, 100,000 people in Massachusetts endured bitter cold nights when the electricity failed. There were more power failures in the most recent ice storm.

There are 3,000 electric utilities in the United States. Sixty large ones, like Consolidated Edison, NextEra Energy, Pacific Gas and Electric, and the Tennessee Valley Authority, supply 70 percent of the nation’s electricity. Nonetheless, the rest are critical in their communities.

All utilities, large and small, have much in common: They are all under pressure to replace coal and natural gas generation with renewables, which means solar and wind. No new, big hydro is planned, and nuclear is losing market share as plants go out of service because they are too expensive to operate.

The word the utilities like to use is resilience. It means that they will do their best to keep the lights on and to restore power as fast as possible if they fail due to bad weather. When those events threaten, the utilities spring into action, dispatching crews to each other’s trouble spots as though they were ordering up the cavalry. The utilities have become very proactive, but if storms are severe, it often isn’t enough.

Now, besides more frequent severe weather events, utilities face the possibility of destabilization on another front, due to switching to renewables before new storage and battery technology is available or deployed.

The first step to avoid new instability -- and it is a critical one -- is to add transmission. This would move electricity from where it is generated in wind corridors and sun-drenched states to where the demand is, often in a different time zone.

Duane Highley, president and CEO of Tri-State Generation and Transmission Association, which serves four states in the West from its base in Westminster, Colo., says new west-east and east-west transmission is critical to take the power from the resource-rich Intermountain states to the population centers in the East and to California.

“Most existing transmission lines run north to south. They aren’t getting the renewables to the load centers,” Highley says.

Echoing this theme, Alice Moy-Gonzalez, senior vice president of strategic development at Anterix, a communications company providing broadband private networks that make the grid more secure and efficient, sees pressure on the grid from renewables and from new customer demands (such as electrical vehicles) as electrification spreads throughout society.

“The use of advanced secure communications to monitor all of these resources and coordinate their operation will be key to maintaining reliability and optimization as we modernize the grid,” Moy-Gonzalez says.

Better communications are one step in the way forward, but new lines are at the heart of the solution.

The Biden administration, as part of its infrastructure plan, has singled out the grid for special attention under the rubric “Build a Better Grid.” It has also earmarked $20 billion of already appropriated funds to get the ball rolling.

Industry lobbyists in Washington say they have the outlines of the Department of Energy plan, but details are slow to emerge. Considered particularly critical is the administration’s commitment to ease and coordinate siting obstacles with the states and affected communities.

Utilities are challenged to increase the resilience of the grid they have and to expand it before it becomes more unstable.

Clint Vince, who heads the U.S. energy practice at Dentons, the world’s largest law firm, says, “We aren’t going to reach the growth in renewables needed to address climate without exponential growth in major interstate transmission. And sadly, we won’t succeed with that goal on our current trajectory. We will need significant federal intervention because collaboration among the states simply hasn’t been working within the timeframe needed.”

Better keep the flashlights handy.

Llewellyn King is executive producer and host of White House Chronicle, on PBS. His email is llewellynking1@gmail.com, and he’s based in Rhode Island and Washington., D.C.

Linda Gasparello

Co-host and Producer

"White House Chronicle" on PBS

Mobile: (202) 441-2703

Website: whchronicle.com

Llewellyn King: Taking the stand for the truth, not a political party; beware false equivalence

An angel carrying the banner of "Truth", in Midlothian, Scotland.

WEST WARWICK, R.I.

I remember the feeling in newsrooms back in the 1960s, as many journalists began to have doubts about the Vietnam War.

In those big workspaces where newspapers come together and broadcasts are assembled, the Vietnam War was taken by journalists to be the good guys versus the bad guys -- the way it had been in the two world wars and the Korean War. But by the mid-1960s, the media were turning against the war.

Some reporters went to Vietnam, the rest of us edited and sometimes melded several files from the war.

Initially, coverage reflected simply what the U.S. commanders were saying in daily briefings from Saigon. As our colleagues on the ground in the war zone began to tell a different story from the official one, editors and writers far from Vietnam began to change their views. Enthusiasm turned to doubt, followed by an anti-war sentiment. The media, in its way, had found its conscience.

Media doubt accelerated as the war dragged on and turned to something close to hostility. I was privy to this because I circulated as a desk editor between three newspapers: the Washington Daily News, the Washington Evening Star, and the Baltimore News-American, finally roosting at The Washington Post.

The American Newspaper Guild passed an anti-war resolution at its annual convention in Dallas in 1969. This side-taking disturbed many journalists. It wasn’t objective, but it passed anyway.

Today, the media landscape is different. There are many more partisan outlets in broadcasting and fewer strong, local newspapers. And there is the whole new world of social media, which defies monitoring. Still the reporting is done by the mainstream media, and from this all-else flows.

While the attitudes of the mainstream are important, they aren’t as commanding as they were in the time of the Vietnam War -- in the time when the nation watched the evening news with total belief and hung on every word from Walter Cronkite.

I have a strong sense of that same struggle between the professional requirement for objectivity and the private conscience is testing the media today just as it did in the days of the Vietnam War.

Can we still cover the divisions of today as an event, as we do most things, or is it morally different?

There is an emerging consensus that journalists collectively -- and a more disaggregated group couldn’t be imagined than the irregular army of nonconforming individualists which make up the Fourth Estate -- are concerned about the survival of democracy. The very basis of our freedoms, of our pride, and even of our history as a free nation capable of the orderly and willing transfer of power is at stake. You can’t work in media now and not feel the sense of the nation going off the rails.

It is, I submit, a turning point when journalists of conscience can’t fall back on the old rules of objectivity, giving one opinion and countering it with another. To give the other side, when you, the writer, know the other side is a contrived lie, is to give credence to the lie and further extend its malicious purpose.

You can’t give the lie the same credence as the truth or you will hide in false equivalence and fail the public.

Even journalists I know who are socially and politically conservative are signing on to the idea that they must take a stand for the truth.

The Big Truth being that Joe Biden won the presidential election, verified over and over again by recounts and court findings. The false equivalence would be to repeat the Big Lie and say at the end of a report, “But supporters of Donald Trump assert the election was rigged.”

When you know that the future of our democracy is in the balance, as a journalist, you feel it is time to take a stand; not to stand with Democrats, but to stand with the truth.

Llewellyn King is executive producer and host of White House Chronicle, on PBS. His email address is llewellynking1@gmail.com and he’s based in Rhode Island and Washington, D.C.

Linda Gasparello

Co-host and Producer

"White House Chronicle" on PBS

Our feathered friends await orders for 2022

Getting our Canada geese in a row for 2022 on the South Branch of the Pawtuxet River at Riverpoint, in West Warwick, R.I.

— Photo by Linda Gasparello of White House Chronicle

The Canada Geese on this branch of the river are like the swallows of San Juan Capistrano. They return in the winter. Their summer gorging ground is the north branch.

Llewellyn King: Climate crisis, population growth and a solution; N.E.'s densest community

WEST WARWICK, R.I.

It wasn’t front and center at the recent climate-change summit, COP26, in Glasgow, but it was whispered about informally, in the corridors and over meals.

For politicians, it is flammable, for some religions, it is heresy. Yet it begs a hearing: the growth of global population.

While the world struggles to decarbonize, saving it from catastrophic sea-level rise and the other disasters associated with climate change, there is no recognition officially anywhere that population plays a critical part.

People do things that cause climate change from burning coal to raising beef cattle. A lot of people equal a lot of pollution equals a big climate impact, obvious and incontrovertible.

In 1950, the global population was at just over 2.5 billion. This year, it is calculated at 7.9 billion. Roughly by mid-century, it is expected to increase by another 2 billion.

There is a ticking bomb, and it is us.

There was one big, failed attempt to restrict population growth: China’s one-child policy. Besides being draconian, it didn’t work well and has been abandoned.

China is awash with young men seeking nonexistent brides. While the program was in force from 1980 to 2015, girls were aborted and boys were saved. The result: a massive gender imbalance. One doubts that any country will ever, however authoritarian its rule, try that again.

There is a long history to population alarm, going back to the 18th century and Thomas Malthus, an English demographer and economist who gave birth to what is known as Malthusian theory. This states that food production won’t be able to keep up with the growth in human population, resulting in famine and war; and the only way forward is to restrict population growth.

Malthus’s theory was very wrong in the 18th Century. But it had unfortunate effects, which included a tolerance of famine in populations of European empire countries, such as India. It also played a role in the Irish Great Famine of 1845-53, when some in England thought that this famine, caused by a potato blight, was the fulfillment of Malthusian theory, and inhibited efforts to help the starving Irish. Shame on England.

The Boston Irish Famine Memorial is on a plaza between Washington Street and School Street. The park contains two groups of statues to contrast an Irish family suffering during the Great Famine of 1845–1852 with a prosperous family that had emigrated to America. Southern New England was a focal point for Irish immigrants to America, and Irish-Americans still comprise the largest ethnic group in much of the region.

The idea of population outgrowing resources was reawakened in 1972 with a controversial report titled “Limits to Growth” from the Club of Rome, a global think tank.

This report led into battles over the supply of oil when the energy crisis broke the next year. The anti-growth, population-limiting side found itself in a bitter fight with the technologists who believed that technology would save the day. It did. More energy came to market, new oil resources were discovered worldwide, including in the previously mostly unexplored Southern Hemisphere.

Since that limits-to-growth debate, the world population has increased inexorably. Now, if growth is the problem, the problem needs to be examined more urgently. I think that 2022 is the year that examination will begin.

Clearly, no country will wish to go down the failed Chinese one-child policy, and anyway, only authoritarian governments could contemplate it. Free people in democratic countries don’t handle dictates well: Take, for example, the difficulty of enforcing mask-wearing in the time of the Covid pandemic in the United States, Germany, Britain, France and elsewhere.

If we are going to talk of a leveling off world population we have to look elsewhere, away from dictates to other subtler pressures.

There is a solution, and the challenge to the world is whether we can get there fast enough.

That solution is prosperity. When people move into the middle class, they tend to have fewer children. So much so that the non-new-immigrant populations are in decline in the United States, Japan and in much of Europe -- including in nominally Roman Catholic France and Italy. The data are skewed by immigration in all those countries -- except Japan, where it is particularly stark. It shows that population stability can happen without dictatorial social engineering.

In the United States, the not-so-secret weapon may be no more than the excessive cost of college.

Llewellyn King is executive producer and host of White House Chronicle, on PBS. His email is llewellynking1@gmail.com and he’s based in Rhode Island and Washington, D.C.

Web site: whchronicle.com

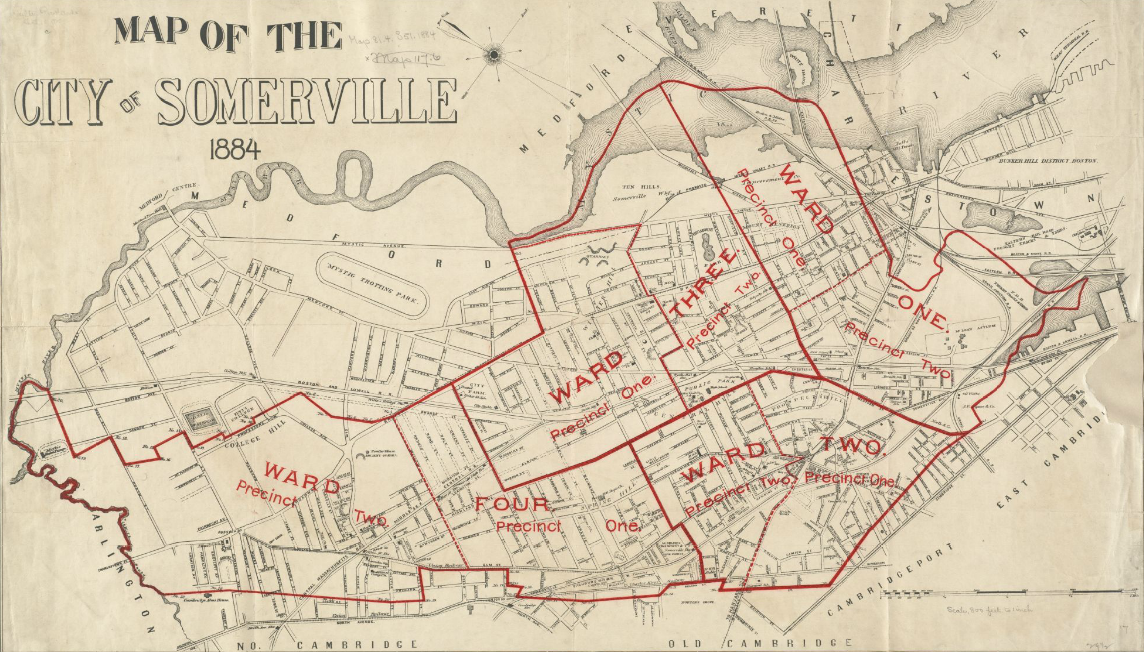

Occupying slightly over 4 square miles, with a population of 81,360 (as of the 2019 Census) (including a myriad of immigrants from all over the world), Somerville is the most densely populated community in New England and one of the most ethnically diverse cities in the nation.

Llewellyn King: The decline of two reliable Christmas gifts

— Photo by Ana Cotta

WEST WARWICK, R.I.

You may have noticed that gift-gifting was a bit more difficult this holiday season. Those two mighty standbys for the gift-givers, perfume and neckties, have moved from the “always welcome’’ list to the ‘‘What was he or she thinking?’’ list.

Perfume – oh, that never-surprising but always-delighting gift – isn’t the gift it used to be. The problem is scent wearing by women has fallen off, as health concerns about volatiles in the air have grown and casual dressing, especially in the time of pandemic, is de rigueur.

Pity – luxury perfume was the unchallengeable gift. It was giving on the strength of its brand, like Miss Dior or Chanel No. 5. Labels really counted in fragrance giving. You were ill-advised to try anything out of the usual. If you espied something called, say, Rocky Mountain Rose, you were advised to eschew it.

The best and easiest to give was Joy by Jean Patou. The fragrance advertised itself as “the most expensive perfume in the world.” Bingo! You couldn’t go wrong if you had the bucks. I used to give a small bottle of Joy to my office manager every year and was thanked with oohs and aahs, even though she knew what was coming. She explained that a woman’s real use of Joy wasn’t so much in wearing it (and she wore it with pleasure), but in displaying it – showing her friends how much her significant other loved her. I rush to say that wasn’t my role in her life.

Neckties were the perfect gift for the man who might have everything. A man couldn’t have too many, and a new one in the style of the day was genuinely welcomed to the sartorial collection.

The necktie is rapidly going the way of spats, detachable collars, and Homburgs, to oblivion.

So shed a tear for the necktie and its infinite giveability. You could play the brand game, but there was no need for that. An obscure neckwear maker, doing a good job with the silk or wool, would be just as fine an accoutrement, as a luxury name like Givenchy or Ralph Lauren. The outstanding exception to this rule was some fabulous work of art by Liberty of London. That would earn deep approval, a friendship cementer.

As a generalization though, an unknown name in neckwear was just as good as the names of the great designers. To those in the know, the best place to buy ties at a reasonable price is, for reasons unknown, at hotel gift shops. Good ties at great prices.

Ties were in their day so important that good restaurants and clubs had selections of ties to fix up men who came with – Shock! Horror! -- an open-necked shirt. The proprietor of a famous Manhattan restaurant of yore, La Cote Basque, told me he wouldn’t serve a king if he wasn’t wearing a tie. La Cote Basque has long gone and so that poor man was never put to the test of facing down royalty.

I wear a bowtie. I have Tucker Carlson – yes, that Tucker Carlson — to thank for that change in my appearance, that bit of sartorial shtick. When I met Carlson, long before he found, as one writer said of someone else, the cramped space to the right of Rupert Murdoch, he was a funny, likable conservative who had just left a CNN talk show and authored an amusing book about the experience of being TV chatterer.

I had him as a guest on my television program, White House Chronicle, on PBS. He was known as a bowtie-wearer and, as a joke, I donned one. I got so many favorable comments that I’ve taken to wearing them instead of the long, silk emblems of the once well-dressed man.

Shame, I say, on the retreat of perfume and the near extinction of the necktie. Women don’t smell so elegant, and men look unfinished.

Llewellyn King is executive producer and host of White House Chronicle, on PBS. His email is llewellynking1@gmail.com and he’s based in Rhode Island and Washington, D.C.

Llewellyn King: Today’s lessons from the 1970’s energy crises

During the 1973-74 part of the 1970’s oil crisis.

WEST WARWICK, R.I.

I’ve been here before. I’ve heard this din at another time. I’m writing about the cacophony of opinions about global warming and climate change.

In the winter of 1973, the Arab oil embargo unleashed a global energy crisis. Times were grim. The predictions were grimmer: We’d never again lead the lives we had led -- energy shortage would be the permanent lot of the world.

The Economist said the Saudi Arabian oil minister, Sheik Ahmad Zaki Yamani, was the most important man in the world. It was right: Saudi Arabia sat on the world’s largest proven oil reserves.

Then as now, everyone had an answer. The 1974 World Energy Congress in Detroit, organized by the U.S. Energy Association, and addressed by President Gerald Ford, was the equivalent in its day to COP26, the UN Climate Change Conference which has just concluded in Glasgow, Scotland.

Everyone had an answer, instant expertise flowered. The Aspen Institute, at one of its meetings, held in Maryland instead of Colorado to save energy, contemplated how the United States would survive with a negative growth rate of 23 percent. Civilization, as we had known it, was going to fail. Sound familiar?

The finger-pointing was on an industrial scale: Motor City was to blame and the oil companies were to blame; they had misled us. The government was to blame in every way.

Conspiracy theories abounded. Ralph Nader told me that there was plenty of energy, and the oil companies knew where it was. Many believed that there were phantom tankers offshore, waiting for the price to rise.

Across America, there were lines at gasoline stations. London was on a three-day work week with candles and lanterns in shops.

In February 1973, I had started what became The Energy Daily and was in the thick of it: the madness, the panic -- and the solutions.

What we were faced with back then was what appeared to be a limited resource base that the world was burning up at a frightening rate. Oil would run out and natural gas, we were told, was already a depleted resource. Finished.

The energy crisis was real, but so was the nonsense -- limitless, in fact.

It took two decades, but economic incentive in the form of new oil drilling, especially in the southern hemisphere, good policy, like deregulating natural gas, and technology, much of it coming from the national laboratories, unleashed an era of plenty. The big breakthrough was horizontal drilling which led to fracking and abundance.

I suspect if we can get it right, a similar combination of good economics, sound policy, and technology will deliver us and the world from the impending climate disaster.

The beginning isn’t auspicious, but neither was it back in the energy crisis. The Department of Energy is going through what I think of as scattering fairy dust on every supplicant who says he or she can help. On Nov. 1, DOE issued a press release which pretty well explains fairy dusting: a little money to a lot of entities, from great industrial companies to universities. Never enough money to really do anything, but enough to keep the beavers beavering.

That isn’t the way out.

The way out, based on what we have on the drawing board today, is for the government to get behind a few options. These are storage, which would make wind and solar more useful; capture and storage of carbon released during combustion; and a robust turn to nuclear power.

All this would come together efficiently and quickly with a no-exceptions carbon tax. Republicans will diss this tax, but it is the equitable thing to do.

Nuclear power deserves a caveat. It is unique in its relation to the government, which should acknowledge this and act accordingly.

The government is responsible for nuclear safety, nonproliferation, and waste disposal. It might as well have the vendors build a series of reactors at government sites, sell the power to the electric utilities, and eventually transfer plant ownership to them.

The government has some things that it alone is able to do. Reviving nuclear power is one.

The energy crisis was solved because it had to be solved. The climate- change crisis, too, must be solved.

Llewellyn King is executive producer and host of White House Chronicle, on PBS. His email is llewellynking1@gmail.com and he’s based in Rhode Island and Washington, D.C.

Llewellyn King: Nuclear power, a victim of an ignorant left-wing assault, urgently needs to be expanded to fight global warming

The Seabrook Nuclear Power Plant, in Seabrook, N.H.

WEST WARWICK, R.I.

If the Biden administration genuinely wanted to get serious about weaning the electric-power sector from fossil fuels, it would get serious about nuclear — not just patting it on the head, as it is doing with the government equivalent of “There, there, baby.”

Nuclear was an early victim of the culture wars that started in the late 1960s, and it remains so to this day.

It is incredible that a source of power, a cutting-edge technology, should have been sidelined for more than 50 years because of fear, suspicion, ignorance and politics.

In the late 1960s, nuclear power became the target of an environmental and political left lash-up. It became part of the environmentalist catechism that nuclear was an evil source of power and must be expunged from the national list of options. The political left didn’t so much as embrace environmentalism as environmentalism embraced the left.

Some environmentalists have had an epiphany, such as the Union of Concerned Scientists, which was founded by Henry Kendall, an activist whom I knew well. We were friends who didn’t agree about nuclear. Now the Union of Concerned Scientists is pro-nuclear, but it was at the barricades against nuclear for decades.

It isn’t that the environmental movement doesn’t want to do the right thing. It does. But it has thought that it alone should decide what was right and good for the environment, and often it has been totally wrong.

The environmental movement turned the nation from nuclear to coal. In the 1970s and 1980s, environmental groups advocated for fluidized bed combustion coal plants. I remember them saying that coal eliminated the need for “dangerous nuclear.” I sat through innumerable meetings and had sparing friendships with such anti-nuclear activists as Ralph Nader and Amory Lovins.

All presidents have said they favor nuclear power, even Jimmy Carter, who was the most reluctant and did huge damage to the United States’ position as the world leader in nuclear energy and technology. Carter wouldn’t say he was opposed to nuclear, but he did talk about it as a last resort and stopped the plans to build a fast-breeder reactor. He also ended nuclear reprocessing, necessitating the disposal of whole nuclear cores, instead of capturing the mass of unburned fuel — thus creating a much larger waste disposal challenge, as well as the need to mine more uranium.

If you believe — and I do — what was said at the COP26 summit in Glasgow, Scotland, now is the time to fix the electric-power industry. It can be fixed by building up nuclear capacity so that electricity can be the go-to, clean fuel of the future. It could replace fossil fuels in everything from cement making to steel production to heating buildings. That potential, that future, is awesome and possible.

Energy Secretary Jennifer Granholm should ask her national laboratories to make recommendations on a nuclear-power future, not to the detriment of wind and solar power, but embracing them.

Wind power is valuable. But depending on it is a little like having a trick knee: You never know when it is going to go out on you.

Europe has just learned that lesson the hard way. It is in the grip of a major energy crisis with electricity prices quadrupling and natural gas prices headed into the stratosphere as winter approaches. One of the causes of this crisis is that wind speeds through the summer fell to their lowest recorded levels in 60 years, with a total wind drought in the normally gale-wracked North Sea.

We won’t get to a carbon-free future unless we have a robust, committed plan to deploy state-of-the-art nuclear plants across the country. We built them in the 1960s and into the 1970s – 100 of them.

Granholm needs to declare a purpose and to pick the proven winner. It is nuclear, and it has been gravely wounded in the culture wars. She needs to rescue it – with word and deed.

Llewellyn King is executive producer and host of White House Chronicle, on PBS. He’s based in Rhode Island and Washington, D.C.

On Twitter: @llewellynking2

Llewellyn King: Using school buses, etc., to store energy in the new electricity revolution

WEST WARWICK, R.I.

Carbon-free electricity isn’t a final destination – it is merely a stop along the road to a time when electricity becomes the clean fuel of choice and reduces pollution in buildings, cement and steel production, transportation and other places and industries.

That is the glorious future that Arshad Mansoor, president and CEO of the Electric Power Research Institute, sees. He revealed his vision on White House Chronicle, the weekly news and public-affairs program on PBS, which I host, on his way to the COP26 summit in Glasgow, Scotland.

Mansoor, who talks about the future with an infectious fervor, was joined on the broadcast by Clinton Vince, chairman of the U.S. Energy Practice at Dentons, the globe-circling law firm, and Robert Schwartz, president of Anterix, a Woodland Park, N.J.-based firm that is helping utilities move into the digital future with private broadband networks.

Mansoor outlined a trajectory in which electric utilities must invest substantially in the near future to deal with severe weather and decarbonization. For example, he said, some power lines must be put underground and many must be tested for much higher wind speeds than were envisaged when they were installed. Some coastal power lines must be raised, he said.

While driving toward a carbon-free future, Mansoor cautioned against utilities going so fast into renewables the nation ignores the ongoing carbon-reduction programs of other industries. Further, if utilities can’t meet the electricity demands of transportation or manufacturing, these industries will turn away from the electric solution.

“Overall, we looked at the numbers and they showed a huge national role in decarbonization for the electric utility industry,” Mansoor said. However, the transition is fraught. It must be managed, sometimes using more gas until the system can be totally weaned from fossil fuels, he said. An orderly transition is vital.

Clinton Vince said the electric utility world has experienced a lot of volatility from severe weather, due to climate change, to the Covid-19 pandemic, and cyber-intrusions. “If I were to boil down to one word what is vital for utilities, it would be ‘resilience.’ ”

Resilience is an ongoing utility goal: It is the ability of a single utility or a group of utilities to bounce back from adversity, often by restoring power quickly. Anterix’s Robert Schwartz said that with his company’s private broadband networks and the deployment of enough sensors, a utility could identify a power line break in 1.4 seconds, before it hits the ground.

One of the most exciting and revolutionary aspects of Mansoor’s thinking is that the consumer will become a partner in the electric utility future. They will join the ecosystem by providing load-management assistance through smart meters, now installed in 60 percent of homes.

Mansoor thinks that the nation’s 480,000 school buses, if electrified, along with private electric vehicles, can be used to store energy. This answers the concern many utility executives have about storage and the concern that a tsunami of electric vehicles will overpower electric supply in the coming decade.

I think the utilities should plan right now for the integration of electric vehicles into their systems. They should offer electric vehicle owners financial incentives for plugging in and sending their stored power to the grid.

Likewise, the utilities should provide rate incentives for off-peak electric vehicle charging. They could do worse than look at the algorithms that have made Uber and Lyft possible, unlocking value in the personal car.

The utilities could devise a flexible system whereby they pay for power when needed and give a price break for charging during off-peak hours, or when there is a surfeit of renewable energy. That is the kind of data flow that will mark the utilities going forward and stimulate demand for private broadband networks.

We, the consumers, will be partners in the electric future, managing our own uses and supporting the grid with our electric cars and trucks. That is Mansoor’s achievable vision.

Llewellyn King is executive producer and host of White House Chronicle, on PBS. He’s based in Rhode Island and Washington, D.C.

On Twitter: @llewellynking2

White House Chronicle

Even ‘real men’ will drive this Ford electric pickup truck

President Biden test-driving a pre-production Ford F-150 Lightning at Ford's Rouge Electric Vehicle Center, in Dearborn, Mich.

WEST WARWICK, R.I.

A huge swath of American drivers and the electric utility industry are waiting for a pickup truck. Not just any pickup truck, but one that could change the way we get around and, for many, how we work.

The pickup truck that’s expected to cause the Earth to move is the all-electric Ford F-150 Lightning. Electric utilities are keeping a wary eye on it and so is an enthusiastic public, jamming Ford’s order books ahead of the arrival of the first trucks next year. Year after year, the gasoline-fueled F-150 has been America’s best-selling truck both for work and pleasure.

In Texas and much of the West, the pickup truck is more than a vehicle: It is a symbol of a way of life and the freedom of the open road. It fits the cowboy inheritance.

But it is also a vehicle for work. Many kinds of work depend on pickup trucks and the Ford F-150 is the leader. Dodge Ram and Toyota Tundra are right behind Ford in this extremely competitive and profitable market.

Builders, carpenters, painters, farmers, delivery services, along with others beyond enumeration, use pickup trucks as the base of their business activity.

In Texas, they are preferred transportation for many individuals and families. With an extended cab, a pickup truck is a car with load-carrying capacity, having the ability to tow a boat, a horse trailer, or a camper with ease.

But they also are luxurious. The interior and the ride of the modern pickup truck is a thing of beauty, the automobile crafters’ art at its zenith. If you haven’t ridden in one, try it. You may never want to stoop to a car again or settle for an SUV, which is a halfway point to the glory of the American pickup truck.

With the Ford F-150 Lightning, workers will be able to plug such electrical equipment as saws, pumps and drills into their trucks.

But there is something else generating grand expectations: It is that the Lightning, if it works as advertised, will turn millions of skeptics into buyers.

All-electric pickup trucks will have a revolutionary impact, especially where driving a truck is the norm. For millions in the South and the West, the new pickup trucks will make electric vehicles socially acceptable, destigmatized. No longer will EVs be the effete preserve of the coastal elites.

That will be a breakthrough for EVs in general and will have a significant impact on the rate at which they are adopted and, consequently, on the rush to install charging infrastructure.

Still, there will be a range of issues. Ford says the basic Lightning (at about $42,000) will have a range of 230 miles; one with two batteries and additional horsepower, costing an additional $10,000, will get 300 miles. If the power-takeoff features are used for operating equipment, the mileage will come down.

Nonetheless, the Lightning is expected to streak across the automotive sky and supercharge the popularity of EVs. If the Lightning performs as expected, it will usher in a whole family of all-electric pickups. It will also speed an increase in demand, which the auto factories won’t be able to meet in the immediate future.

The utilities will have to get ready, too.

Texas, which has one of the largest, if not the largest, penetration of pickup trucks per capita, may be facing electricity shortages in the years ahead. Data companies have been moving to the state, putting a strain on electricity demand.

Andres Carvallo, a polymath friend, is a former electric utility executive and now is a principal at CMG Consulting and a professor at Texas State University. He points out the possible stress on electric utilities. “ERCOT [Electricity Reliability Council of Texas] is about an 80-gigawatt energy market at peak capacity today. There are around 22 million registered vehicles in Texas,” he says, “If they were all-electric and each had a 100-kWh battery, they would require 2,200 gigawatts to charge at the same time. So how do you manage the gap?”

Down the road, Texas and the rest of the country is going to need an awful lot of new, clean electricity.

Of course, there won’t be 100 percent deployment of electric vehicles for many decades, and they won’t all be charging at the same time. But this shouldn’t escape the electric utilities, which have to plan now for then.

When real men start driving all-electric rigs, things will happen — revolutionary things.

On Twitter: @llewellynking2

Llewellyn King is executive producer and host of White House Chronicle, on PBS. He’s based in Rhode Island and Washington, D.C.

Llwelleyn King: Good reasons to venerate the gig economy

Professional dog walker

WEST WARWICK, R.I.

Napoleon didn’t deride the English as “a nation of shopkeepers,” although that phrase is commonly attributed to him. In fact, it was Bertrand Barère de Vieuzac, a French revolutionary who used it when attacking the achievements of British Prime Minister William Pitt, the Younger.

I think that Napoleon was too smart not to have realized that a nation of shopkeepers is a strong nation, and that if the English of the time were indeed a nation of shopkeepers, they would constitute a more formidable enemy.

A nation of shopkeepers, to my mind, is an ideal: self-motivated people who know the value of work, money and enterprise; and who are almost by definition individualists. So, I regret the constant threats to small business coming from chains, economies of scale, high rents and some social stigma.

But mostly I regret that in our education system, self-employment isn’t celebrated and venerated as being equivalent to work at larger enterprises. We define too many by where they work, not by what they do.

I have always believed that one should aspire to work for oneself, to eschew the temptations of the big, enveloping corporation and to strike out with whatever skills one has to test them in the market and to have the customer, not the boss, tell you what to do.

Our education system produces people tailored to be employed, not self-employed.

But things are changing. The gig economy was well underway before the COVID-19 pandemic hit, and now it is roaring. Many employees found that the servitude of conventional employment wasn’t for them.

The gig world differs from the small business world that I have described in that it is small business refined to its absolute core: a one-person business, true self-employment.

There are many advantages in self-employment for society and for the larger business world. Hiring a self-employed contractor is easier for a company, not having to create a staff position and pay all the costs that go with it. Laying off a contractor isn’t as traumatic. The worker is more respected, and is asked to do things not commanded. The system gains efficiency.

But if employers come to see the gig economy as just cheap, dispensable labor, then the gig economy has failed.

The gig worker shouldn’t expect security but should be treated in a business-to-business environment. He or she needs to know how to drive a bargain and to have the moral courage to ask for a contract that is fair and recognizes the value that is intrinsic in the gig relationship.

I am a fan of Lyft and Uber. They offer self-employment to anyone with a driver’s license and a car — and the companies will even get you into a car. But the bargain is one-sided. The driver has the freedom to work what hours he or she chooses but not to negotiate the terms of their engagement. That is decided by a computer in San Francisco.

This gig worker can’t hope to hire other drivers and start a small business: It doesn’t pass the gig contract concept. I have talked to many ride-share drivers. They revel in the freedom but not the income.

Gig workers can be, well, anything from a plumber to a computer programmer, from a dog walker to an actuary.

But for the free new world of gig working to become part of our business fabric, the social structure needs to be adjusted by the government to allow for the gig worker to enroll in Social Security and to charge expenses against taxes as would an incorporated business. Jane Doe, who makes a living designing websites, needs to know that she is a business, not just freelancing between jobs.

A friend who has been self-employed for many years told me recently that he was being considered for a big staff job. I told him to be mindful that he will be trading away some dignity and a lot of freedom. It is hard to get into a harness when you have been running free.

I hope we get many more workers running free. Napoleon would have understood.

On Twitter: @llewellynking2

Llewellyn King is executive producer and host of White House Chronicle, on PBS. He’s based in Rhode Island and Washington, D.C., and his email is llewellynking1@gmail.com

White House Chronicle

Llewellyn King: We're living in an earthquake

WEST WARWICK, R.I.

I have been in only one earthquake. It was in Izmir, Turkey, in 2014. The earth moved, undulating under my feet. Buildings shook and people’s fear could be felt.

Americans have reason to believe they are in a societal earthquake of unknown intensity or long-term consequence. Everywhere the earth we have known and trusted — political, social, economic, technological, and international — seems to be moving. Institutions are shaking, technology is obliterating the familiar; new and disturbing politics is rampant, left and right; and palpable climate change has arrived.

Our foreign skill set has been found wanting. Fear for the future is resident in our consciousness.

Our politics may be the most shaken of our intuitions. What we used to know how to do — like conduct an election — is in question and the fixes, as in conservative-introduced voting bills, threaten what we have held to be secure, those very elections. Electoral results are widely distrusted in a way they never have been previously.

We used to think we knew how to educate children. Now, that is in doubt as political factions fight over the curriculum, to say nothing of masks for children. To quote a vintage ad, “What’s a mother to do?”

The COVID-19 virus continues its ravages, reduced but not vanquished. It has left its mark: It has reshaped work and play to an extent we don’t yet understand. There are jobs, at least 10 million, going begging and workers who don’t want those jobs. They range from demand for drivers and warehouse personnel, reflecting the revolution in shopping, to airport workers, hospital staff, and, of course, restaurants.

Even the aerospace industry is begging. The Northrop Grumman plant in Maryland has a huge banner facing the Amtrak tracks seeking new hires.

It is a great time to change careers, obviously.

We don’t know whether work-at-home regimes will stay or whether the human need to congregate will win out. Do you move far from the office or wait out the phenomenon?

Technology controls our lives, and that isn’t always easy to live with. Try talking to any airline, insurance company, bank, or state agency and you will need a thorough familiarity with computers because the person on the line, or the recording, wants you off the telephone and online. This, even if you called because you were stymied online, to begin with.

If you get to a human, usually in Asia, that soul likely won’t have the advantages which come with having English as a first or second language. Hard-to-reach firms’ biggest asset isn’t, as they used to say, you, the customer. You don’t count to any large organization. Stop complaining and wait for a “customer-care representative,” who will tell you to get lost after you’ve waited for hours. You are now an insignificant part of mega-data, which some in the data business have called the new oil. Some corporate websites don’t publish a phone number. Don’t bother the tranquility of the C-suite.

The poor, who should be the beneficiaries of the new technologies, are victims. Take the unbanked: That large number of people who don’t have credit cards or a bank account. They can’t get rides from Uber or Lyft, and taxis are almost completely absent from city streets.

The unbanked can’t, should they be able to afford it, check into a hotel without plastic, or make a reservation for tickets to travel or go to a concert. They are non-members of society. They are on the wrong side of the digital divide — and that is a bleak place to be. Theirs are the children who got no education during the lockdowns and who will suffer through all their lives as a result. If you miss the techno train, you walk along tracks behind it.

The rise of China has damaged our self-esteem and we fear we are looking into the chasm of cold war or worse. Likewise, the calamitous end of our time in Afghanistan has further weakened our faith in our ability to get it right. (Heck, even “Jeopardy” can’t pick a host.) Our intelligence agencies seem to have totally failed, and our military doesn’t appear to be the winning institution we have been so proud of for so long.

After an earthquake, nations rebuild the structures. We need to start rebuilding with our institutions, and first among those is buttressing the democratic system. An invincible voting rights act would be a good starting place.

Our democracy hasn’t fallen yet, but it is shaking as the ground shifts under it.

Llewellyn King is executive producer of White House Chronicle, on PBS. He’s based in Rhode Island and Washington, D.C., and his email is llewellynking1@gmail.com

On Twitter: @llewellynking2

Llewellyn King: A life in journalism: fascination and panic

WEST WARWICK, R.I.

A young man asked me for advice on a career in journalism. The following is the letter I sent to him.

For advice about a career in journalism, I may not be the person to ask

I dropped out of school at 16 because I wanted to be a journalist. I wanted to know the great figures of my time and to travel the world. Journalism has not let me down.

To me, newspapering is almost a sacred calling. You can air injustice and celebrate genius. It is true, personal freedom: You always, at heart, work for yourself within a framework of your employment. You can talk to anyone in any office in any country and expect to be allowed an audience.

In the end, it is between you and the reader. We need income to practice our trade, but our communic is always between the writer and the reader.

The commodity is news. It is news in the humblest local paper or The Washington Post. Jack Cushman, who worked for me as the editor of Defense Week, and who became a star at The New York Times, told me once, "You used to tell me when I was writing a story, 'Come on, Cushman, you won't write it better in The New York Times.' You know what? I don't."

The message is: Be defined by what you write, not for whom you write it. But, of course, we all want to succeed and the measure of success can be where we work; that, I grant, and I have been a pursuer of good jobs everywhere, having worked for Time and Life as a very young stringer in Africa, the Daily Mirror and the BBC in London, The Herald Tribune in New York, and The Washington Post in Washington.

I am so much a journalistic romantic, I still get a thrill seeing my byline in any paper, big or small.

The work is simpler than people let on. Dan Raviv, then with CBS Radio, defined it for me this way, and I have never heard it said better, "I try to find out what is going on and tell people." Quite so.

I don't draw a line between magazines and newspapers, print and broadcast, or the Internet: The work is the same. The key of C, in which it is all centered, is still the newspaper, but that is changing. The struggle for accuracy, fairness and getting at the news never changes.

My first wife, the brilliant English journalist Doreen King, said that to succeed you need the "inner core of panic." That is fear that you made a mistake in a story: got a number wrong (billions not millions, for example), that you misspelled a name, and that you didn't fully understand what you were told in your reporting. The public doesn't know that we really struggle to get it right, often without the luxury of time -- an unending struggle.

Writing columns is something of an art, and some have it and some don't. A column is a newspaper within a newspaper; your own space to give evidence and share ideas. They are a fantastic form of journalism, but they aren't for everyone. To be a reporter you need news judgment. What is news? It is indefinable but if you don't have it, try something else. A test of news judgment is to watch the Sunday morning talk shows and write a mock story. Then survey what the other outlets have picked on and see if you found the same things newsworthy. You will know soon enough if you have news judgement.

I have been writing columns since the very beginning of my career. A young woman, who worked for me on The Energy Daily, was one of the finest reporters I have ever known. But when she was appointed the editorial page editor of a newspaper, she found it hard. Opinion didn't come easily to her. Facts were her domain. She moved to Europe, where she worked for a business information service and flourished. Her meticulous reporting was what was needed there.

If, like me, you have opinions about everything, then writing columns comes easily and the rest is technique. Read how others handled their material. Not what they opined, but how they managed it.

I don't hold that there is any difference between the needs of newspapers and magazines. I believe that news services or newspapers give you a grounding in the disciplines of writing that are very useful in magazine writing.

Journalism can be a hard life. A lot of journalists have money problems, drink to excess, and are known to have messy private lives. But, by God, we tell the world what is going on, and that is to be part of something huge and fabulous. It is a life of sheer adventure. I am glad of it.

Llewellyn King is executive producer and host of White House Chronicle, on PBS. His email is llewellynking1@gmail.com and he’s based in Rhode Island and Washington, D.C.

Llewellyn King: Don’t kid yourself: Solutions to global warming won't be simple

WEST WARWICK, R.I.

The latest report from the United Nations Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change gives humanity a simple directive: Get a grip on greenhouse-gas emissions or the dear old planet won’t be the dear old planet we have known and loved down through the millennia.

Sounds simple, huh? Like wearing a face mask or getting a COVID-19 vaccine shot.

That is the trouble. Everyone will have his or her own science and won’t hesitate to inflict it on anyone who disagrees, whether it is verified or not.

Social nagging is about to become a national pastime. I can hear it now: “Why do you drive a gasoline car? You know, your fire pit is a carbon source.” Or “Did you think about the carbon consequences when you booked your vacation in Europe?”

How ghastly the moral superiority of the anti-carbon warriors will be! I can imagine them saying “I can’t imagine why people don’t buy electric cars. We have had one for three years.” Or “Your oil-heated house is a pollution source. We have installed solar rooftop panels. Passive solar houses should be mandated by the government.”

Remember the anti-smoking crusaders? I am afraid that you haven’t seen anything yet. The very real climate threat is going to unleash a whole new tribe of social scolds.

Electric utilities are in the crosshairs and there will be no end to their vilification. Watch out for the environment experts, who once urged the use of coal over nuclear, to take charge of the future with some other counterproductive policy nostrum.

All that said, I believe if we don’t get on top of the greenhouse-gas emissions problem, we soon will be wondering, as Robert Frost wrote, “Some say the world will end in fire,/ Some say in ice.” The way it is going, I say the world will end in devastating floods and heat waves, worsening droughts and accelerating sea-level rise.

The U.N.’s climate change panel has declared a clear and present danger. It is a threat that has been growing and largely laughed off over 50 years. I, for one, first heard of the idea of global warming in 1970, when it seemed very remote and a little crazy. It is neither remote nor crazy now. It is at hand, and it should affect a lot of thinking.

In the near term, common sense would have us ship our natural gas abroad so that China, India and many other countries stop burning coal; not as the anti-carbon warrior would have us close down our production. The best longer-term hope is more science on carbon capture and nuclear power. It is foolish to worry about nuclear waste lasting 10,000 years when, if we keep on the current climate trajectory, life won’t exist in the nearer future on planet Earth.

The fact is that while the science of climate change is well understood, the solutions aren’t. For example, those who would denounce natural gas, which is far less polluting than coal, don’t know the lifecycle costs of the two advocated alternatives, wind and solar.

To build a windmill, you need a large concrete base and a steel tower, both of which are manufactured through carbon-intensive processes. At the end of the life of a turbine, about 25 years, the giant blades, which are mostly made of carbon fiber-reinforced fiberglass, will be disposed of in landfills. The blades can’t be recycled, unlike the steel towers and other components.

Both the manufacture and disposal of solar cells have considerable environmental impact. The impact in making them is known, but the impact of their disposal in landfills isn’t known.

Going forward, the need is to know the science, encourage innovation and not to bow to culture activists who would wish their solutions on the rest of us. When I was a boy, asbestos was the miracle substance, recommended for inclusion in everything because it was fire-resistant. If you didn’t use asbestos, the fire alarmists came down on you. The moral? Beware of simple solutions to complex problems.