Llewellyn King: Prepare for a summer of discontent but enjoy the sun anyway

Heading down to Crane Beach, in Ipswich, Mass.

— Photo by Thomas Steiner

Roller coaster at the Six Flags amusement park in Agawam, Mass. More political/geopolitical roller coaster rides coming.

WEST WARWICK, R.I.

All the portents are that 2022 will be a summer to remember --and not in a good way.

It will be a summer of shortages, high prices, possible electric blackouts and severe and unpredictable storms. It also promises to be a summer of political ugliness, where civility and facts are missing.

National unity and cohesion, which usually can be expected in times of crisis, isn’t in sight. We are gracelessly at each other’s throats.

Also missing will be any sense that there is strong leadership anywhere; not in the White House, Congress, or among our allies.

Set these tribulations, caused by a dangerous war in Ukraine following on the COVID 19 pandemic, and you are entitled to be despondent. All this wasn’t in the playbook -- the events that shape the world never are.

But don’t reach for the arsenic. For most of us, glorious summer, so important to the North American lifestyle, will be as it always is with crowded beaches, jammed highways, chaotic airports and painful sunburn. We will have summer; and summer will have its joys, its rituals, and its happiness.

For Americans, these aren’t the worst of times. They are just very trying times. We will feel them directly in the wallet, painfully so. Gasoline and other fuels will be very expensive, and heating oil will be a big-ticket item next winter. House prices are still stratospheric, and rents are going up. The markets are shaky.

Americans are feeling that all isn’t well and that things are coming unstuck -- reliable, everyday things.

In democracies, we seek relief by changing the government. All the indications are that we will do that in the midterm elections just months away.

The Democrats are likely to take a drubbing. The Republicans will joyfully seize victory – and they won’t know any better what to do about the great stresses that are shaking the nation and the world.

Instead, they will be tempted to double down on social issues and a raft of things that will exacerbate the divisions in the country, further curb the rights of women, mess with education curricula, seek to influence social media platforms, and keep the government firmly in gridlock.

President Biden and his unlucky administration will get the blame if the Democrats are routed in the midterms. Indeed, it should, fairly or not, even though the alternative may not be better.

Certainly, a Democratic White House and Republican Congress suggests just one thing: crippling inaction.

Biden hasn’t been a proactive president but a reactive one. He has waited for the water to rise before he has acknowledged that it is happening, and it is time to start bailing.

Take, for example, the U.S. withdrawal from Afghanistan. When Biden tried to get ahead of the news, to identify an issue and resolve it before it mugged him, he got it terribly wrong. It was a foreign-policy calamity of Biden’s making, and it seems to have curbed his enthusiasm for preempting issues.

Mostly, Biden has sought to balance things. His reaction to outrageousness is a sedate, genteel sense of horror. You expect him to say to the Supreme Court, or the gun lobby, or Russian Vladimir Putin, “Look what you have done!”

One gets the feeling that Biden doesn’t have a grip on much except his decency. Everyone who knows him will tell you what a decent man he is. Decency supports, but it doesn’t lead. Decency isn’t a policy. It isn’t a way forward. It isn’t a solution.

After the midterms, Congress likely will be in the hands of two ruinous vacillators, Sen. Mitch McConnell, of Kentucky, and the even more wobbly Rep. Kevin McCarthy, of California. They aren’t exemplars of the Republican ideal. They aren’t in the previously worshipped Ronald Reagan tradition.

Both have shown themselves captive to former President Trump’s vengeful malevolence and have twisted the truth in their servitude to him.

Politics are sour, prices high, the future bumpy, but summer is glorious. Revel in it, celebrate it, and bask in its untroubled rays. I plan to do just that. Thoughts of politics are worse than sunburn.

Llewellyn King is executive producer and host of White House Chronicle, on PBS. His email is llewellynking1@gmail.com and he’s based in Rhode Island and Washington, D.C.

Llewellyn King: For society’s sake, newspapers, whose work is looted by tech firms, deserve a reprieve

WEST WARWICK, R.I.

Newspapers are on death row. The once great provincial newspapers of this country, indeed of many countries, often look like pamphlets. Others have already been executed by the market.

The cause is simple enough: Disrupting technology in the form of the Internet has lured away most of their advertising revenue. To make up the shortfall, publishers have been forced to push up the cover price to astronomical highs, driving away readers.

One city newspaper used to sell 200,000 copies, but now sells less than 30,000 copies. I just bought said paper’s Sunday edition for $5. Newspapering is my lifelong trade and I might be expected to shell out that much for a single copy, but I wouldn’t expect it of the public to pay that — especially for a product that is a sliver of what it once was.

New media are taking on some of the role of the newspapers, but it isn’t the same. Traditionally, newspapers have had the time and other resources to do the job properly; to detach reporters to dig into the murky, or to demystify the complicated; to operate foreign bureaus; and to send writers to the ends of the earth. Also, they have had the space to publish the result.

More, newspapers have had something that radio, television and the Internet outlets haven’t had: durability.

I have a stake in radio and television, yet I still marvel at how newspaper stories endure; how long-lived newspaper coverage is compared with the other forms of media.

I get inquiries about what I wrote years ago. Someone will ask, for example, “Do you remember what you wrote in 1980 about oil supply?”

Newspaper coverage lasts. Nobody has ever asked me about something I said on radio or television more than a few weeks after the broadcast.

I was taken aback when, while I was testifying before the Senate Foreign Relations Committee decades ago, a senator asked me about an article I had written years earlier and forgotten. But he hadn’t and had a copy handy.

There is authority in the written word thay doesn’t extend to the broadcast word, and maybe not to the virtual word on the Internet in promising new forms of media like Axios.

If publishing were just another business – and it is a business — and it had reached the end of the line, like the telegram, I would say, “Out with the old and in with the new.” But when it comes to newspapers, it has yet to be proven that the new is doing the job once done by the old or if it can; if it can achieve durability and write the first page of history.

Since the first broadcasts, newspapers have been the feedstock of radio and television, whether in a small town or in a great metropolis. Television and radio have fed off the work of newspapers. Only occasionally is the flow reversed.

The Economist magazine asks whether Russians would have supported President Vladimir Putin’s invasion of Ukraine if they had had a free media and could have known what was going on; or whether the spread of COVID in China would have been so complete if free media had reported on it early, in the first throes of the pandemic?

The plight of the newspapers should be especially concerning at a time when we see democracy wobbling in many countries, and there are those who would shove it off-kilter even in the United States.

There are no easy ways to subsidize newspapers without taking away their independence and turning them into captive organs. Only one springs to mind, and that is the subsidy that the British press and wire services enjoyed for decades. It was a special, reduced cable rate for transmitting news, known as Commonwealth Cable Rate. It was a subsidy but a hands-off one.

Commonwealth Cable Rate was so effective that all American publications found ways to use it and enjoy the subsidy.

United Press International created a subsidiary, British United Press, which flowed huge volumes of cable traffic through London.

Time Inc. had a system in which their cable traffic was channeled through Montreal to take advantage of the exceptionally low, special rates in the British Commonwealth.

That is the kind of subsidy that newspapers might need. Of course, best of all, would be for the mighty tech companies to pay for the news they purloin and distribute; for the aggregators to respect the copyrights of the creators of the material they flash around the globe. That alone might save the newspapers, our endangered guardians.

Llewellyn King is executive producer and host of White House Chronicle, on PBS. His email is llewellynking1@gmail.com and he’s based in Rhode Island and Washington, D.C.

Llewellyn King: Biden's conflicted policies on natural gas; is a carbon-capture breakthrough coming?

Model of the LNG tanker Rivers. It was built in 2002 and is registered in Bermuda. Its capacity is 137,500 cubic meters of gas.

WEST WARWICK, R.I.

Joe Biden at war and Joe Biden at peace aren’t the same person. When it comes to the Russia-Ukraine war and energy policy, the U.S. president is severely conflicted.

Central to Biden’s strategy has been to cut off Russia’s huge revenues from exporting natural gas to Europe. He has unambiguously declared that the shortfall Europe will have in natural-gas supplies from Russia will, in time, be remedied with other sources, especially with liquefied natural gas (LNG) exports from the United States.

So far so good. But Biden has always favored the environmental vision of the left wing of his own party and its implacable resistance to all forms of carbon-based fossil fuels because of their contribution to global warming.

Europe imports one third of the natural gas it needs for electric generation, heating and other domestic uses by pipeline from Russia. Particularly vulnerable is Germany, which depends on half of its gas imports from Russia: a dependency which it has happily allowed to grow year after year.

That was worsened when Germany turned its back on nuclear, aided by its influential Greens, after Japan’s Fukushima disaster, in 2011.

Charlie Riedl, executive director of Center for LNG at the Natural Gas Supply Association, said on my weekly PBS program, White House Chronicle, it will take several years to boost U.S. LNG exports to Europe and will need substantial infrastructure investment.

The United States has six operating export LNG terminals and a seventh nearly ready to enter operation. Europe has 26 main receiving terminals and eight smaller ones. Each new U.S. terminal has a price tag of around $20 billion, Riedl confirmed. Similarly, tankers must be available and gas exporters, like Qatar, are increasing their tanker fleets.

The impediments to building new natural-gas infrastructure in the United States are formidable. On the same broadcast, Sheila Hollis, acting executive director of the U.S. Energy Association, a nonpartisan, non-lobbying group that embraces all energy, explained, “I don’t think there is any easy way to make anything happen of this magnitude in the country, regardless of what infrastructure you’re building, or which industry’s infrastructure.

She went on to say, “I do think it will remain an ongoing saga of slogging your way through the morass of regulations, both state and federal of every conceivable variety, and the strong opposition that comes from entities like financing communities and universities that may have a particular interest in reducing CO2; and because of the magnitude, it is one that will be lit on in the regulatory setting, in the judicial setting, and in the legislative setting, both state and federal, because that is the nature of the beast.”

Moreover, Hollis said, there are environmental-justice sensitivities: “Who gets the work? Where will the facilities be sited? And there will be extreme attention to environmental issues at the facilities and the pipelines.”

Biden is caught between his own plans to cut fossil-fuel use in electric supply in the nation and his commitment to Europe that the United States will be a reliable supplier of fuel for their electricity needs over the long haul.

Commitment is important to the gas industry, which is whipsawed between demands for natural gas and attempts to limit its use by obstructing development. New natural-gas infrastructure will need to operate over several decades to recover investment -- at odds with the Biden plan to reduce fossil-fuel generation in the United States by 2030 and get to net zero by 2050.

A bright spot: The industry is confident that sometime in the future, carbon can be removed from natural gas at the time of combustion. This technology is called carbon capture, utilization and storage (CCUS) and envisages getting the carbon out of the combustion effluent before it goes into the air. It can then be used as a building material and for future gas and oil well stimulation.

According to USEA’s Hollis, the Department of Energy is working with its national laboratories and is making solid progress in perfecting the technology. Energy aficionados believe increasingly that a breakthrough is at hand.

If that is so, then Biden can shush his environmental critics and approach the future with more confidence, giving gas companies and utilities the durable assurances they need.

Meanwhile Biden is bullish on future gas in Europe and bearish on gas in the United States. As in the Johnny Mercer song, “something’s gotta give.”

Llewellyn King is executive producer and host of White House Chronicle, on PBS. His email is llewellynking1@gmail.com, and he’s based in Rhode Island and Washington, D.C.

Llewellyn King: We must face the fact that world crises in food, inflation and energy require tough decisions and new thinking

Messengers going to Job, each with bad news.

— 1860 woodcut by Julius Schnorr von Karolsfeld

WEST WARWICK, R.I.

There is a rough road ahead for the world and our political class isn’t leveling with us.

As Steve Odland, president and CEO of The Conference Board, one of the nation’s premier business-research organizations, said in a television interview, serious inflation will continue at least until 2024, and longer if things continue to deteriorate with supply-chain crises and the war in Ukraine.

Particularly, Odland, who also serves as a director of General Mills Inc., fears a global food crisis with famine in Africa and many other vulnerable places if Ukrainian farmers don’t start seeding spring crops to start this year’s harvest. Already, Ukraine – once known as one of the world’s breadbaskets -- has cut off exports to make sure that there is enough food for their own people, as war rages.

Odland sees U.S. inflation continuing at 7 to 8 percent for several years at best. But his primary worry is global food supplies, as countries face a crisis of new and frightening proportions.

His second worry is stagflation. If the rate of productivity falls below 3 percent, “then we will have stagflation,” Odland told me during a recording of White House Chronicle, on PBS, the weekly news and public affairs program I produce and host.

Odland faults the Federal Reserve for being timid in raising interest rates to counter inflation.

I fault the political class for not leveling with us – both parties. As we are in a state of perpetual election fervor, we are also in a state of perpetual happy talk. “Get the rascals out, and all will be well when my band of happy angels will fix things.” That is what the political class says, and it is a lie.

We are in for a long and difficult period which began with the pandemic that disrupted supply chains and set off inflation, and now the war in Ukraine has compounded that. Supply chains won’t magically return to where they were before COVID-19 struck, and more likely they will have further constrictions because of the war. New supply chains need to be forged and that will take time.

For example, nickel, which is used in the batteries that are reshaping the worlds of electricity and transportation and for stainless steel, will have to come from places other than Russia. At present, Russia supplies 20 percent of the world’s voracious appetite for high-purity nickel. Opening new mines and expanding old ones will take time.

The world’s largest challenge is going to be food: starvation in many poor countries and high prices at the supermarkets in the rich ones, including the United States. There are technological and alternative supply fixes for everything else, but they will take time. Food shortages will hit early and will continue while the world’s farms adjust. There will be suffering and death from famine.

The curtailing of Russian exports will affect the United States in multiple ways, some of which might eventually turn out to be beneficial as the creative muscle is flexed.

In the utility industry, someone who is thinking big and boldly is Duane Highley, president and CEO of Tri-State Generation and Transmission Association in Denver.

Highley told Digital 360, the weekly webinar that emanates from Texas State University in San Marcos, the challenging problem of electricity storage could be solved not with lithium-ion batteries, but with iron-air batteries.

In its simplest form, an iron-air battery harnesses the process of rusting to store electricity. The process of rusting is used to produce power when it is exposed to oxygen captured on site. To charge the battery, an electric current reverses the process and returns the rust to iron.

Clearly, as Highley said, this won’t work for electric vehicles because of the weight of iron. But in utility operations, these batteries could offer the possibility of very long drawdown times --not just four hours, as with current lithium-ion batteries. And there is plenty of iron stateside.

Another Highley concept is that instead of dealing with all the complexities of transporting hydrogen, it should be stored as ammonia, which is more easily handled.

This isn’t magical thinking, but the kind of thinking which will lead us back to normal -- someday.

Politicians should stop the happy talk and tell us what we are facing.

Llewellyn King is executive producer and host of White House Chronicle, on PBS. His email is llewellynking1@gmail.com, and he’s based in Rhode Island and Washington, D.C

Llewellyn King: Helping America by helping Ukrainian refugees resettle in U.S. counties that could use more people

Wheat field in Idaho. Ukraine, like the U.S., is a very big wheat producer.

WEST WARWICK, R.I.

The Ukrainian diaspora is upon the world. Of the millions who are dispossessed by Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, it is wishful thinking that on some glorious day they will all go home. In reality, the world will have to accommodate them. They can’t all stay in Poland and Romania.

One by one, the countries of Europe falteringly are stepping up to their moral and humanitarian duty. Most countries say they will take some Ukrainian refugees.

The Biden administration, without clarity, has indicated that some refugees will be welcomed. What the administration is hoping is that these will be glommed onto existing Ukrainian communities in several cities.

This might be a mistake. The cities with large Ukrainian communities are New York, Chicago, Philadelphia, Los Angeles, Detroit, Cleveland and Indianapolis. In all these cities, housing is expensive and in very short supply; and there are many social problems for those at the bottom, where refugees traditionally find themselves.

Now comes an extraordinary proposal for refugee resettlement from an attorney, Christopher Smith, who practices in Macon, Ga. He is also the honorary consul there for Denmark, but he tells me his proposal is in no way a reflection of that office and is entirely his own as a private citizen.

Smith’s sweeping and enticing proposal is that refugees from Ukraine should be settled, with federal and state assistance and with the participation of local government, not in crowded cities but in American counties which have been losing population for decades. “Those include counties here in south Georgia,” Smith told me by telephone.

You may think, from anecdotal reporting, that there is a major move from cities to the country, spurred by COVID. But Smith tells me that movement is small and doesn’t reverse the decades-long trend of county depopulation.

My own observation of this COVID-induced trend is that it applies to such places as New York and Boston, where the outward movement has been to garden locales where virtual commuting can be accomplished, for example, people who have moved from Boston and New York to Rhode Island and Connecticut, and from Los Angeles to smaller outposts, or north to Washington and Oregon.

Smith said in a position paper: “There are 3,143 counties in the United States. From 2010 to 2020, approximately 1,660 (53 percent) of American counties lost population. Here in Georgia, 67 (42 percent) of 159 counties saw a reduction in population during that time span. Most but not all American counties that lost population during this 10-year period are located in rural areas.”

While counties tend to have a higher apartment and rental home vacancy rate and a lower cost of living than the national average, many of these communities have job shortages, Smith said.

“Logic would suggest that these communities would be an ideal location to host Ukrainian refugees,” he said.

The thing that struck me about Smith’s proposal is how thoroughly he has researched it. He hasn’t just sprouted an idea, he has worked out a plan and enshrined it in a draft act of Congress, which lays out the federal, state and county responsibilities and the issuance of work permits and residence certificates -- and, of course, the all-important issue of funding. He has sent it to his congressman, Austin Scott, a Republican.

Smith told me that it is worth noting that Scandinavians were encouraged to populate the Midwest -- as anyone who listened to Prairie Home Companion, on NPR knows.

I don’t know whether America’s wheat farmers need help, but certainly there will be pressure to grow more wheat. The chances that wheat will be sown in the middle of Russia’s war on Ukraine are unlikely. Ukraine is a huge wheat producer. Canada brought in Ukrainian immigrants in the 1890s to help boost wheat production. It was a great success.

It seems to me that Smith’s well-conceived proposal has merit and deserves attention. It has the prima facie merit of helping a part of America that needs help, and giving succor to the most desperate of people, those uprooted by war.

Llewellyn King is executive producer and host of White House Chronicle, on PBS. His email is llewellynking1@gmail.com, and he’s based in Rhode Island and Washington, D.C.

--

Co-host and Producer

"White

Llewellyn King: Trying to spread the innovation culture to old businesses

100, 300, and 500 Technology Square, in Cambridge, Mass., as seen from Main Street. The neighborhood has been the site of many technological breakthroughs for decades.

WEST WARWICK, R.I.

Microsoft is buying, subject to regulatory approval, Activision Blizzard for $69 billion. The Internet of Things is white-hot and likely to remain so.

If you want to whistle at that humongous sum for a company that makes games, you may have to add many octaves to the known musical scale.

Yes, high-tech is chasing trivia. The imperative at work here is if you don’t get your latest game into the market, someone else will. The threshold of entry is low and the rewards are astronomical.

If you are talking innovation and creativity, you are talking the Internet. That means that whole areas of society aren’t progressing as fast as they might and should. There is asymmetry.

The Internet firmament is driven not by market demand, but by a business dynamic that exists in the world of internet entrepreneurism: Innovate and create because the internet can create great wealth — and take it away, too.

Most non-Internet companies — and I talk to a fair number of CEOs — say that they are innovative and that they are innovation-driven but, in fact, they aren’t. Most companies don’t need to innovate the way the internet giants do. The metaverse is demonstrably an unstable place.

Most companies are looking for stability, for a plateau where they can manage what has been created while adding to it cautiously, often by acquisition. They confuse innovation with evolutionary improvement. The last thing they want is the kind of destructive innovation that characterizes Silicon Valley.

The febrile need to innovate in the Internet world is unique to that world. This because internet companies are all on a treacherous slope; failure can come as fast as success. Remember MySpace, Nokia, Palm, and Wang?

The Internet is global, and it is intrinsically favorable to monopoly. In the internet world, first past the post takes the prize money — all of it.

When you have market caps that value a company at $1 trillion, and all of that is dependent on the next innovation not overtaking you, you are going to throw money and talent at innovation because the alternative is known. Whenever possible, you are going to buy up your competition, hence the Microsoft purchase.

With all of the money, all of the glamor, all of the talent, there also is fear that some kid in a garage somewhere will invent the next big thing.

I submit that for the non-Internet world the business dynamic is very different. Most CEOs of public companies, snug in their C-suites and buttressed by huge salaries, are seeking a quiet place; a plateau where profits grow but there is some business serenity. For example, Boeing doesn’t want new airframes, it wants upgraded models.

They won’t admit to it, but many businesses long to be rent takers (known collectively as rentiers). They want a steady income with small risk.

Unfortunately, the business culture, including that spawned in business schools, aims to channel ambition into the rent-taking model. We have a business culture where ambition is channeled toward climbing to the top of the established order, not creating a new order.

There are many excellent minds managing established companies, often established many decades earlier, but there are few who yearn to create something wholly new.

The great names of management are many, but the great names of true innovation are few. Almost always, they have to break away from the established to create the new, to alter the world.

My friend Morgan O’Brien, the co-creator of Nextel, and now the executive chairman of the pioneering wireless company Anterix, is that kind of innovator who saw new horizons and went for them.

Today’s standout inventor is Elon Musk. He began as an Internet whiz with PayPal and has blazed the innovation trail like no other since Thomas Edison, more than a century earlier. He has changed the world underground with new concepts of subways, changed surface transportation by going electric, and changed space with his rockets.

Thirty years ago, I wrote that the weakness of U.S. companies is that they are happy to make silent movies when the talkies have been invented. Today, the established auto manufacturers are hell-bent to make electric pickup trucks now that new entrepreneurs are in the truck market with electric trucks. They never wanted to abandon the internal-combustion engine, just improve it a little at a time.

If the dynamic of the Internet and its constant innovation is missing in most American businesses, it needs to be grafted onto the business body politic. Must the Internet be behind every innovation of consequence? Ride-sharing and additive manufacturing (3D printing) are all computer-driven — software at work.

The challenge for the business culture is to harness ambition – it is never in short supply — and point it not toward the greasy pole of promotion, but toward the firmament of innovation.

On Twitter: @llewellynking2

Llewellyn King is executive producer and host of White House Chronicle, on PBS. He’s based in Rhode Island and Washington, D.C.

White House Chronicle

Linda Gasparello: Millennials can be pioneers in cities with cheap houses

In Danville, Va., home of tobacco entrepreneur William T. Sutherlin, called by locals the "Last Capitol of the Confederacy.’’ But most houses there don’t look like this!

WEST WARWICK

Millennials are supercharging the U.S. housing market. They have lots of cash, and they’re making a dash for cities like Boise, Idaho, Raleigh, North Carolina, Tampa, Florida, and Austin, Texas.

As home-mortgage rates rise and inventory shrinks in those and other A-list cities, Millennials, particularly those who can work remotely, might want to consider C-list – C for cheap -- cities.

Hey, Millennial. Don’t be bummed about being outbid for that pricey “adorable vintage house within walking distance to entertainment” in Austin (actually, a teardown with a honky-tonk a few yards from the back porch). Be cheered that Wall Street 24/7, a news and financial site, has just released a special report entitled “The Cheapest City to Buy a Home in Every State.”

If you’re a pioneering Millennial, here are a few cities in the report:

Gary, Ind., could be “your home sweet home” -- just like the line from the song in The Music Man, which was a hit on stage and screen long before you were born. The median home value is $66,000. Cheap homes abound in this not-so-cheerful city.

Flint, Mich., The fact that you can’t drink the water is no problem for you because you’ve only ever drunk bottled water. The median home value is $29,000. If you decide to buy a home there, keep buying bottled water from fresh municipal springs -- in other states.

Camden, N.J. There is great news for home buyers. Trenton has taken the “Murder Capital of New Jersey” title away from Camden, a perennial titleholder. The median home value in Camden is a bargain $84,000 versus $335,600 for New Jersey as a whole. Camden is downriver from Trenton, so mind the floating corpse risk.

Minot, N.D. It’s a hot market: the median home value is $208,700 versus $193,900 for the state. As for temperature, it’s not. I had a school friend from Minot who told me the saying there was, “Why not Minot? Because freezing is the reason.” Look at those months of frigid temperatures as being the reason to get more wear out of your chichi Canada Goose Expedition Parka.

East St. Louis, Mo. One resident, in a review on the Niche site, wrote, “I didn't like all of the abandoned homes and buildings. It looked like the area isn't livable and then two houses down, it is livable.” The Niche reviewers give the city bad marks for violence, but great ones for the high school football team and the diners. The median house value is $54,000.

The city that really caught my eye in the report was Danville, Va. – in a state where I lived for most of my life.

For years, because I’m interested in architecture, I’ve pored through listings on historic house sites. Recently on one site, there were many dilapidated Victorian houses listed in Danville’s Old West End, priced from $15,000 to $55,000.

For much of its history, Danville was a D-list city – D for disreputable. This tobacco-processing and textile-manufacturing city’s reputation rolled downhill for a century, from the Civil War (where it was major center of Confederate activity and was the “Last Capital of the Confederacy” from April 3-7, 1865) to “Bloody Monday,” the name given to a series of arrests and brutal attacks that took place during a nonviolent protest by Blacks against segregation laws and racial inequality on June 10, 1963. Of the protests, leading up to the March on Washington on Aug. 28, the Rev. Martin Luther King Jr. preached, “As long as the Negro is not free in Danville, Virginia, the Negro is not free anywhere in the United States of America.”

Danville’s work in recent decades to create a new identity is paying off. The median home value is $90,500. The city is attracting high-tech companies and Millennial workers – new residents who will continue its transformation from disreputable to desirable.

Linda Gasparello is co-host and producer of White House Chronicle, on PBS. Her email is lgasparello@kingpublishing.com, and she’s hased in West Warwick, R.I. and Washington, D.C.

Llewellyn King: How I fell for Taylor Swift big time

Taylor Swift

WEST WARWICK, R.I.

If Taylor Swift sat next to me on a bus – an unlikely confluence — I wouldn’t know that she was a famous singer, an idol to millions of young people (who call themselves Swifties), and especially to young women. But I have fallen for her big time.

Popular culture – with which I’ve never been very familiar, even when I wrote about movies and the theater -- has given me a wider-and-wider berth as time has passed. Truth is that I am more familiar with the evolution of technology than I am with the history of pop music, more comfortable with Turner Classic Movies than I am with this year’s releases.

This from a man who was paid by the London Dispatch to follow Elizabeth Taylor and Richard Burton around London when they were making Cleopatra — and making whoopee -- in 1962.

I might mention that when I did catch up with the most famous lovers of the day, they were lunching in a pub near where I lived in the leafy Dulwich area of South London. They were everything you would want of lovers: they glowed, held each other’s eyes, and were so clearly in the thralls of enchantment that I didn’t call for a photographer, or in any way fulfill my assignment for the newspaper. It was an active dereliction of duty, but they were so compelling.

The Romantic poet Lord Byron -- who knew a thing or two about adulterous love -- described an adulterous pair as “happy in the illicit indulgence of their innocent desires.” Taylor and Burton seemed to be lost in their affair, and then it was adultery -- they were both married, although later they wed each other, twice.

So much as I have been aware of the couplings of the rich and famous since those days, I have thought of them as tawdry. If you had seen Taylor and Burton in love, you would have dined at the table of the gods: love, fame, wealth and talent in one sublime package.

Enter Taylor Swift. I had gleaned indirectly -- the way one picks up information about subjects that don’t really interest one -- that she has had a string of lovers and almost ritually wrote songs about them. Self-indulgent, I thought. So many not very good modern singers seem to sing about themselves and their luckless love lives. Sing what you know, as it were.

So how come I’m head over heels for Swift? I have said I don’t know what she looks like, and I don’t believe I would recognize her music -- that is until I listen to the lyrics.

I met Swift and fell for her on one of those Web sites that aggregates quotations. I tell you the woman is a poet, a remarkable poet of love and its turbulence.

Just take just these lines from four different songs:

“Who could ever leave me, darling/But who could stay?”

“You’re not my homeland anymore/So what am I defending now?”

“You kept me like a secret/But I kept you like an oath.”

“Cold was the steel of my axe to grind/For the boys who broke my heart/Now I send their babies presents.”

They are so elegant and so true that they belong up among the great lyrics of the great love songs of the musical theater, the world of Ira Gershwin, Cole Porter, Lorenz Hart, Oscar Hammerstein, and others from the golden age.

I don’t expect to meet her, nor do I have any special desire to. But if I did, I would say, “Keep writing, Taylor. You comfort young hearts and light up old ones.”

Llewellyn King is executive producer and host of White House Chronicle, on PBS. His email is llewellynking1@gmail.com and he’s based in Rhode Island and Washington, D.C.

Holiday House (the white house on the left) is Taylor Swift’s home in the Watch Hill section of Westerly, R.I.

— Photo by JJBers

Llewellyn King: We can’t welcome all who want to emigrate here; identity politics threatens America

Illustration from Walter Crane's Columbia's Courtship: A Picture History of the United States in Twelve Emblematic Designs in Color with Accompanying Verses (1893). Back then, most immigrants were expected to assimilate into American culture, learning English, etc. A smaller percentage do now, with the rise of identity politics. and “multiculturalism.’’ Too many immigrants continue to see the countries they came from, as awful as they are, as home.

U.S. Border Patrol agents review documents of individuals suspected of attempted illegal entry from Mexico.

The American head and heart aren’t in alignment on immigration. They are savagely apart.

The head argues that all those people amassing on the U.S.-Mexico border, or living in camps across the English Channel, or trying to get into Turkey from Syria should be sent home. The heart argues that people anywhere denied a reasonable life in the place in which they were born are entitled to find what they seek: freedom from want. It argues, too, that immigrants have made us wealthy down through the centuries.

The head is adamant: Unfettered immigration is conquest one person at a time — one ragged child, one desperate mother, one hopeful man. Immigration is destabilizing much of the Middle East, particularly Jordan and Lebanon. It is threatening Europe and is changing the face of the United States.

Bad governance has an impact beyond the borders of the badly governed country.

Small stretches of sea that separate Malta, Greece, Italy and Spain’s Canary Islands from Africa haven’t deterred migrant crossings. If these migrants are accepted by European countries, they will bring with them their religion, their language, and their loyalty to the culture that they left behind.

Before the jet age and the communications revolution, an immigrant sought to be a new American, a new Briton, or a new Frenchman. Many of today’s immigrants don’t feel compelled to assimilate and can reside in North America or Europe but retain the aims and culture of the country from which they came.

I know Koreans who have lived in the United States for decades and speak no English — and have no need to. All their wants are met in Korean, from banking to television to shopping. I also know U.S.-born Salvadorans who talk about El Salvador as “my country.” The wheels have come off assimilation.

The receiving countries deserve some blame for those who remain alien. The prevailing identity politics doesn’t meld a nation. The “woke” reverence for every culture except its native culture and language is destructive.

The immigrants who flooded the United States in the 19th Century and the first half of the last century came to assimilate, with many refusing to teach their children their native tongues. Now immigrants think and feel as though they are the citizens of other countries. It is easy to do, and “multiculturalism” is the facilitator.

American hearts go out to those who are living in hell on the southern border: Frightened, in need of food, in need of places to sleep and to defecate, often sick, preyed on by criminals in their own number, and believing myths — especially the myth that when Donald Trump lost the presidential election, they would be welcome in the United States.

The heart says immigration is good for us and that we are all immigrants; that our generous inheritance, from the genius of the Founding Fathers to the syncopation of jazz and the blues to the techno-wonders of Elon Musk, is the product of immigration.

But my heart and my head, and those of many Americans, align in believing that we have to stop identity politics, treasure our American identity and explain to the world that the United States isn’t open to all, otherwise all would come.

The Trump administration failed to end illegal immigration with its incompetence, its bluster and its wall. So far, the Biden administration has done worse. It has allowed a myth to circulate around the world that if you get to Latin America, even to faraway Chile, you can get into the United States.

President Biden should demand that Vice President Kamala Harris, who he put in charge of the border, do her job and produce some ideas. Her declaration that she will work to strengthen the countries of Central America so that their people stay home is fantasy.

Even if Harris could do that, she should note that the new flood of migrants is coming from across the world — from Haiti to Pakistan and other parts of Asia. U.S. intelligence has failed, and the vice president fails daily to address this global problem, which will only get worse as the climate changes and the seas rise. The brain reels and the heart bleeds.

On Twitter: @llewellynking2

Llewellyn King is executive producer and host of White House Chronicle, on PBS. He’s based in Rhode Island and Washington, D.C.

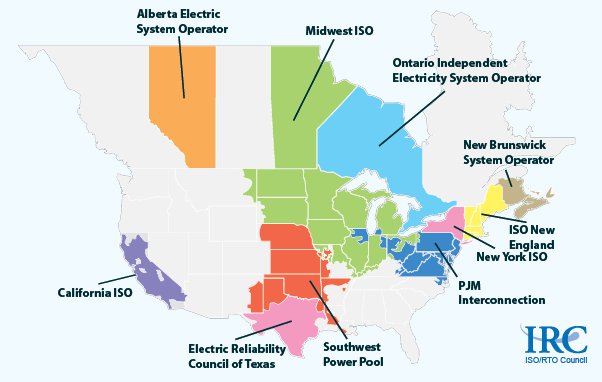

Llewellyn King: Shutting off natural gas can dangerously destabilize the electricty grid

Fields Point liquified natural gas facility, in Providence

WEST WARWICK, R.I.

It has been an annus horribilis for the nation’s electric utility companies. Deadly storms and wildfires have left hundreds of thousands -- and for short periods millions -- of electricity customers without power, sometimes for days and weeks.

These destructive weather events have come at a time when utilities are being squeezed from all directions: by customer needs, by activists’ demands, by state regulators, and by the zero-carbon urgency of the Biden administration as expressed in its bill, the Build Back Better Act, to upgrade and overhaul the nation’s infrastructure.

The utilities themselves have set ambitious carbon-emission-reduction goals, but in some cases, they still can’t meet the demands of the government. They are caught between the clear need to harden their infrastructure against severe weather and shuttering their reliable but polluting coal plants and mothballing their dependable gas turbines.

This predicament caused Jim Matheson, president of the National Rural Electric Cooperative Association, which represents hundreds of utilities, mostly small, in rural areas, to ask Congress to make exceptions, or at least to understand that things can’t be changed overnight. In a letter to House Committee on Energy and Commerce Chairman Frank Palone (D.-N.J.) and ranking minority member Cathy McMorris Rogers (Wash.), Matheson said there was concern with the Clean Electricity Performance Program (CEPP) part of the bill.

“The CEPP’s very narrow, 10-year program implementation window is unrealistic. The electric co-ops have existing contractual obligations and resource development plans that extend for several years, if not decades. Many of those plans continued deployment of a diverse set of affordable, clean electricity sources, but not all those plans align with the CEPP. …. The narrow implementation window also limits our ability to take advantage of technologies like energy storage, carbon capture, or advanced nuclear, which are unlikely to be deployable in the near term,” Matheson said.

The predicament of utilities is that there is no reliable storage and that the two principal sources of renewable power, wind and solar, are subject to the vagaries of weather. During Winter Storm Uri, which hit Texas last February, solar, along with all other sources of energy, froze under sheets of snow and ice. The result was disaster and heavy loss of life.

In that instance, gas didn’t save the day: Lines and instruments froze, and what gas was available was sold at astronomical prices.

The lesson was clear: Prepare for the worst. That lesson was repeated in a series of hurricanes, including this year’s devastating Ida, which plunged parts of Louisiana into the dark for more than a week.

If the lesson hasn’t been grasped in the United States, it is being repeated in Europe right now: A unique wind drought that lasted six weeks has left the European grid reeling and has thrown Britain into a full energy crisis.

The issue is not that alternative energy -- wind and solar for now -- isn’t the way to go to reduce the amount of carbon spewing into the atmosphere. Instead, it is not to destabilize what you have by prematurely taking gas offline.

Gas has certain useful qualities not the least of which is that it can be stored. Storage is the bugaboo of alternative energy. Batteries are good for a few hours at best and the other main way of storing energy, pumped storage, requires large expenditures, substantial engineering, and a usable site. It requires the creation of a big water impoundment, which will provide hydro when extra power is needed. It works, it is efficient, and it isn’t something that you build in a jiffy.

I have spent half a century writing about the electricity industry and when it comes to decarbonization, I can say that while many in the industry were doubtful about global warming at one time, the industry now is committed to eliminating carbon emissions by 2050.

The joker is storage or some other way of backing up the alternatives. That may be hydrogen, but a lot of research and engineering must take place before it flows through the pipes which now carry natural gas. Likewise, for small modular reactors.

The Economist, pointing to Europe, says that the Europeans have destabilized their grid by failing to prepare for the transition to alternatives, triggering a global natural gas shortage. Gas should be used sparingly and treasured. The trick is to throw out the bath water and save the baby.

Llewellyn King is executive producer and host of White House Chronicle, on PBS. His email is llewellynking1@gmail.com and he’s based in Rhode Island and Washington, D.C.

Llewellyn King: As climate warms, utilities must become much more resilient

The severe flooding in Greater New York, New Jersey and New England from the remnants of Hurricane Ida, that storm’s devastation in New Orleans and much of the rest of Louisiana and the winter freeze in Texas usher in a new reality for the electric industry, showing how outdated their infrastructure has become and how they have to much more expect the unexpected.

Resilience is the word used by the utilities to describe their ability to speedily restore power, to bounce back after an outage. This year, resilience has been put to the test with major challenges affecting electric utilities from coast to coast. Mostly, the results have been disappointing to catastrophic.

It is reasonable to believe that resilience means that if there is an outage power will be back on forthwith or within hours, and that is often the case.

But as the attacks on the system from aberrant weather have become more frequent and severe, the bounce back has been closer to struggle back slowly.

Two cases tell a tale of catastrophe. Recently, the complete loss of electricity to New Orleans during Hurricane Ida, much of which is still in the dark and with people suffering without water in their homes, along with the absence of light, air conditioning, or the ability to charge a cell phone.

Even before Ida tore into the Gulf Coast, teams from other utilities were on their way to help. ConEd in New York was one of many utilities that had trucks rolling to the scene before Ida hit. That kind of quick, fraternal response is often what is meant by resilience. Bold and well-coordinated though it may have been, it was not nearly enough. Entergy, which supplies the power to the area, failed the resilience test.

The other standout was in the failure of the Texas grid when Winter Storm Uri struck in the middle of February. It froze much of Texas for five days and more than 150 people died, some by freezing to death in their homes. The unfortunately named Electric Reliability Council of Texas (ERCOT), which operates the electric grid of Texas, abominably failed the resilience test.

Some of the natural-gas supply was cut off during the deep freeze because the system hadn’t been weatherized, but the gas that did flow also flowed money.

The gas operators made enormous profits, including Energy Transfer, which made $2.4 billion. Not only had the gas operators not signed on to the concept of resilience, but the idea of commonweal was absent.

While electric utilities -- there are a few large electric utilities and more than 80 small ones in Texas -- struggled to honor their mandate to serve, the gas suppliers, according to those in the electric utility industry, served their mandate only to their shareholders.

Rayburn, the electric cooperative that has a service area near Dallas, spent what it had budgeted for three years in just five days on gas purchases, CEO David Naylor told me.

On my PBS show, White House Chronicle, Paula Gold-Williams, president and CEO of CPS Energy, the large, municipally owned gas and electric utility in San Antonio, said she thought that the suppliers of gas to electric generators should be regulated as Texas utilities are.

Wildfires in the West, storms in the East and up the center of the country have put a huge strain on the electric utilities. What is clear is that “resilience” needs to be defined in a much broader sense. That whole infrastructure of the electric-utility industry needs to be re-examined with a view to surviving monstrous weather. The cost in lives and in treasure is very high when electricity, the essential commodity of modern life, fails.

This new imperative comes at a bad time for the electric-utility industry, which is struggling with daily cyber-attacks, converting from fossil fuels to alternatives, and straining to find new, durable storage systems.

One of the trends to greater security is to encourage microgrids – small, self-contained grids that can store and generate electricity, often from renewables like solar. These can disengage from the grid in times of stress and continue providing power to the microgrid.

Other suggestions include undergrounding electric lines. California’s Pacific Gas and Electric has proposed undergrounding 10,000 miles of lines to counter wildfires sparked by downed cables. The cost might be insupportably high -- over $1 million a mile in level ground, according to one estimate.

Entergy, according to The Energy Daily, has 2,000 miles of lines down in New Orleans. Burying just the most vulnerable lines in the nation would be a massive civil engineering undertaking at a daunting cost. Other ideas, please?

Llewellyn King is executive producer and host of White House Chronicle, on PBS. His email is llewellynking1@gmail.com, and he’s based in Rhode Island and Washington, D.C.

Long Island Expressway in New York City shut down due to flooding as the remnants of Hurricane Ida swept through the Northeast on Sept. 1-2

— Photo by Tommy Gao

Llewellyn King: A life in journalism: fascination and panic

WEST WARWICK, R.I.

A young man asked me for advice on a career in journalism. The following is the letter I sent to him.

For advice about a career in journalism, I may not be the person to ask

I dropped out of school at 16 because I wanted to be a journalist. I wanted to know the great figures of my time and to travel the world. Journalism has not let me down.

To me, newspapering is almost a sacred calling. You can air injustice and celebrate genius. It is true, personal freedom: You always, at heart, work for yourself within a framework of your employment. You can talk to anyone in any office in any country and expect to be allowed an audience.

In the end, it is between you and the reader. We need income to practice our trade, but our communic is always between the writer and the reader.

The commodity is news. It is news in the humblest local paper or The Washington Post. Jack Cushman, who worked for me as the editor of Defense Week, and who became a star at The New York Times, told me once, "You used to tell me when I was writing a story, 'Come on, Cushman, you won't write it better in The New York Times.' You know what? I don't."

The message is: Be defined by what you write, not for whom you write it. But, of course, we all want to succeed and the measure of success can be where we work; that, I grant, and I have been a pursuer of good jobs everywhere, having worked for Time and Life as a very young stringer in Africa, the Daily Mirror and the BBC in London, The Herald Tribune in New York, and The Washington Post in Washington.

I am so much a journalistic romantic, I still get a thrill seeing my byline in any paper, big or small.

The work is simpler than people let on. Dan Raviv, then with CBS Radio, defined it for me this way, and I have never heard it said better, "I try to find out what is going on and tell people." Quite so.

I don't draw a line between magazines and newspapers, print and broadcast, or the Internet: The work is the same. The key of C, in which it is all centered, is still the newspaper, but that is changing. The struggle for accuracy, fairness and getting at the news never changes.

My first wife, the brilliant English journalist Doreen King, said that to succeed you need the "inner core of panic." That is fear that you made a mistake in a story: got a number wrong (billions not millions, for example), that you misspelled a name, and that you didn't fully understand what you were told in your reporting. The public doesn't know that we really struggle to get it right, often without the luxury of time -- an unending struggle.

Writing columns is something of an art, and some have it and some don't. A column is a newspaper within a newspaper; your own space to give evidence and share ideas. They are a fantastic form of journalism, but they aren't for everyone. To be a reporter you need news judgment. What is news? It is indefinable but if you don't have it, try something else. A test of news judgment is to watch the Sunday morning talk shows and write a mock story. Then survey what the other outlets have picked on and see if you found the same things newsworthy. You will know soon enough if you have news judgement.

I have been writing columns since the very beginning of my career. A young woman, who worked for me on The Energy Daily, was one of the finest reporters I have ever known. But when she was appointed the editorial page editor of a newspaper, she found it hard. Opinion didn't come easily to her. Facts were her domain. She moved to Europe, where she worked for a business information service and flourished. Her meticulous reporting was what was needed there.

If, like me, you have opinions about everything, then writing columns comes easily and the rest is technique. Read how others handled their material. Not what they opined, but how they managed it.

I don't hold that there is any difference between the needs of newspapers and magazines. I believe that news services or newspapers give you a grounding in the disciplines of writing that are very useful in magazine writing.

Journalism can be a hard life. A lot of journalists have money problems, drink to excess, and are known to have messy private lives. But, by God, we tell the world what is going on, and that is to be part of something huge and fabulous. It is a life of sheer adventure. I am glad of it.

Llewellyn King is executive producer and host of White House Chronicle, on PBS. His email is llewellynking1@gmail.com and he’s based in Rhode Island and Washington, D.C.

Llewellyn King: Don’t kid yourself: Solutions to global warming won't be simple

WEST WARWICK, R.I.

The latest report from the United Nations Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change gives humanity a simple directive: Get a grip on greenhouse-gas emissions or the dear old planet won’t be the dear old planet we have known and loved down through the millennia.

Sounds simple, huh? Like wearing a face mask or getting a COVID-19 vaccine shot.

That is the trouble. Everyone will have his or her own science and won’t hesitate to inflict it on anyone who disagrees, whether it is verified or not.

Social nagging is about to become a national pastime. I can hear it now: “Why do you drive a gasoline car? You know, your fire pit is a carbon source.” Or “Did you think about the carbon consequences when you booked your vacation in Europe?”

How ghastly the moral superiority of the anti-carbon warriors will be! I can imagine them saying “I can’t imagine why people don’t buy electric cars. We have had one for three years.” Or “Your oil-heated house is a pollution source. We have installed solar rooftop panels. Passive solar houses should be mandated by the government.”

Remember the anti-smoking crusaders? I am afraid that you haven’t seen anything yet. The very real climate threat is going to unleash a whole new tribe of social scolds.

Electric utilities are in the crosshairs and there will be no end to their vilification. Watch out for the environment experts, who once urged the use of coal over nuclear, to take charge of the future with some other counterproductive policy nostrum.

All that said, I believe if we don’t get on top of the greenhouse-gas emissions problem, we soon will be wondering, as Robert Frost wrote, “Some say the world will end in fire,/ Some say in ice.” The way it is going, I say the world will end in devastating floods and heat waves, worsening droughts and accelerating sea-level rise.

The U.N.’s climate change panel has declared a clear and present danger. It is a threat that has been growing and largely laughed off over 50 years. I, for one, first heard of the idea of global warming in 1970, when it seemed very remote and a little crazy. It is neither remote nor crazy now. It is at hand, and it should affect a lot of thinking.

In the near term, common sense would have us ship our natural gas abroad so that China, India and many other countries stop burning coal; not as the anti-carbon warrior would have us close down our production. The best longer-term hope is more science on carbon capture and nuclear power. It is foolish to worry about nuclear waste lasting 10,000 years when, if we keep on the current climate trajectory, life won’t exist in the nearer future on planet Earth.

The fact is that while the science of climate change is well understood, the solutions aren’t. For example, those who would denounce natural gas, which is far less polluting than coal, don’t know the lifecycle costs of the two advocated alternatives, wind and solar.

To build a windmill, you need a large concrete base and a steel tower, both of which are manufactured through carbon-intensive processes. At the end of the life of a turbine, about 25 years, the giant blades, which are mostly made of carbon fiber-reinforced fiberglass, will be disposed of in landfills. The blades can’t be recycled, unlike the steel towers and other components.

Both the manufacture and disposal of solar cells have considerable environmental impact. The impact in making them is known, but the impact of their disposal in landfills isn’t known.

Going forward, the need is to know the science, encourage innovation and not to bow to culture activists who would wish their solutions on the rest of us. When I was a boy, asbestos was the miracle substance, recommended for inclusion in everything because it was fire-resistant. If you didn’t use asbestos, the fire alarmists came down on you. The moral? Beware of simple solutions to complex problems.

Llewellyn King is executive producer and host of White House Chronicle, on PBS. His email is llewellynking1@gmail.com and he’s based in Rhode Island and Washington, D.C.

Web site: whchronicle.com

Solar panels on a house in a Boston suburb. Massachusetts is very big on green energy, at least rhetorically.

— Photo by Gray Watson

Llewellyn King: Nuclear literacy can save nuclear power

The Millstone Nuclear Power Station, on Long Island Sound in Waterford, Conn.

WEST WARWICK

In its first two decades of service, the Douglas DC-3 -- maybe the most amazing, safe and hardworking aircraft ever built -- was denounced in folk legend as wildly unsafe. It was branded a flying coffin by those who didn’t know the data.

The myth that it wasn’t airworthy matured into an out-and-out lie. In fact, the DC-3 was the workhorse that rapidly accelerated modern passenger aviation.

The DC-3 was saved by growing aviation literacy in the public. Can nuclear literacy save nuclear power, one of the greatest tools in containing global warming? I believe that it can. Literacy trumps myth and superstition.

While nuclear power has comparisons with the venerable DC-3, it is far more important than any single airplane. Those who turn their backs on nuclear power -- so needed as climate change accelerates – are akin to those who without knowledge were turning their backs on passenger aviation in 1935.

Today’s major public argument against nuclear power is that it leaves behind radioactive materials -- lumped together as nuclear waste – which will be radioactive for 10,000 years, about twice recorded human history.

This argument conjures up images of a monster, breaking out of its repository and marching the Earth, laying waste to whatever stands in its way -- a nuclear blob from a science fiction movie.

Truth is, in about 200 years, most high-level nuclear waste will have decayed into something less radioactively aggressive. In the first 30 years, it gets less toxic and more manageable.

As this explanation by William Reville, an eminent emeritus professor of biochemistry at University College Cork, published in the Irish Times, explains succinctly, “ The intense radioactivity reflects the preponderance of short-lived radioisotopes that are disintegrating quickly.

“This high rate of nuclear decay means the level of radioactivity declines quickly – the radioactivity of spent nuclear fuel reduces to 10-20 percent of its initial activity within six months of its removal from the reactor and within a few decades, the radioactivity reduces by a further factor of two. Radioactivity danger is largely gone within 100 years and within a few thousand years, the stored spent fuel is little more radioactive than the uranium ore that first came out of the ground to be fabricated into new fuel rods.”

Despite this science, when I advocate nuclear, which I have done for a long time, people roll their eyes and say, “What about the waste?” The waste does need to be stored safely, but it decays to a safe state quite quickly.

The most agonized-over nuclear material is the transuranic plutonium. Yes, it will last thousands of years, but it is easily shielded because it is an alpha emitter: It can’t penetrate human skin and can be blocked with a piece of notepaper. Natural uranium, found in rocks nearly everywhere, is an emitter, as is thorium, found in conjunction with rare earths. Radiation is everywhere. It isn’t the devil’s incarnation.

Those facing the climate crisis tend to shy away from nuclear and advocate only wind and solar. Little thought is given to the waste that these low-density energy sources are themselves going to produce.

Wind will create a huge volume of physical waste from the disposal of carbon-fiber turbine blades. These don’t recycle, unlike the steel towers on which the turbines rest. Eventually, tens of millions of tons of solar panels will make their way to landfills.

If you want to fret about waste -- and you should -- look to the garbage that is crowding the landfills, especially plastic which doesn’t break down. Look to the billions of tons of junk that is making its way into the oceans, killing marine life, and shudder.

The Earth can take a lot of nuclear waste from power plants, advanced medicine and reactors aboard navy ships and spacecraft. But can it take much more of the alternative?

Aviation literacy saved aviation from myth, even after disasters. Myth is a dangerous force when it is the foundation of policy.

If you want a good, safe myth, go with the tooth fairy.

Llewellyn King is executive producer and host of White House Chronicle, on PBS. His email is llewellynking1@gmail.com, and he’s based in Rhode Island and Washington, D.C.

Linda Gasparello

Co-host and Producer

"White House Chronicle" on PBS

Mobile: (202) 441-2703

Website: whchronicle.com

ReplyReply allForward

Llewellyn King: Has COVID launched a new age for workers?

Most workers would like to slash the time they spend commuting.

WEST WARWICK, R.I.

Millions of Americans appear to be echoing the words of the Johnny Paycheck song “Take This Job and Shove It.” This is a sentiment that is changing the work scene, the way we work, and the future of work.

The workers of America are shuffling the deck in a way that has never happened before. It is accentuating an acute labor shortage.

I receive lists of job openings every day and the common denominator seems to be that you must show up at a place of business. Among the big and seemingly frantic employers are FedEx, Walmart and Amazon. Warehouse workers and delivery drivers are the most sought-after employees.

To overcome the labor shortage, wages are rising and adding to the rising inflation -- although what part of that rise is labor cost isn’t clear. Other factors are pandemic-induced supply chain disruptions, a tightening of food flows from California and other Western states, and the acute housing shortage. The economy is rebalancing; and so are workers, reassessing their lives and making changes.

There has been a severe shortage of skilled workers for a long time. It has been felt almost everywhere from construction to electric line workers. It is just worse now, exacerbated by immigration restrictions and workers who have joined the reshuffle.

During the COVID-19 lockdown, millions of individuals have assessed what they do and, apparently, found it wanting.

America’s workforce isn’t returning to the jobs that they held before the lockdown. Some are trying new things; others are demanding changes in the workplace. There is a demand for more remote working. The rat race is running short of willing rats.

Commuting seems to be the one big no-no. People in the major work hubs such as New York, Washington, Chicago, Boston and San Francisco have sampled the joys and the failings of working from home, and commuting has lost.

I know people who used to spend four or five hours every day getting to work and back home in all these cities. Sitting in a traffic jam is neither creative nor the best use of human life, these people are now saying.

In the movie Network, Peter Finch bellows, “I’m as mad as hell, and I’m not going to take this anymore!” That is the new sentiment towards rigid travel and rigid work schedules. Working from home has taken people up the hill and shown them the valley, and they have liked the valley.

Other workers, particularly at the lower end of the work scale, have wondered whether they wouldn’t be happier doing something else now that they have had time to ponder. A friend of mine’s daughter who was a professional waiter in Florida now works for a printer. She has found she gets a more dependable income, better hours and that incalculable: a happier work environment.

I love small business, and I believe it to be the essential force for innovation and job creation. But it is also where petty boss-tyrants flourish. Lousy, egomaniacal employers aren't hard to find, especially in the restaurant business.

When I worked as a waiter in New York, between journalism jobs, I knew waiters who dreamed of the great restaurant where the tips are generous and, above all, the “patron is nice.” Unseen, there is a lot of cussing and pressure in any restaurant, and job security is unknown.

Enforced downtime has caused many to wonder whether they are even in the right line of work; whether the money, prestige or social recognition that may have gone with their old job was worth it.

For others, the gig economy has beckoned, where the employer has been cut out. Particularly, this is true of young people in communications and related work. Geeks are a hot item and can contract directly. But others, from landscape gardeners to plumbers, are going gig. The downside is there are no benefits, from Social Security deductions to pensions and health care. Society is lagging in recognizing this new arena of work.

Peculiarly, we aren’t at full employment. Unemployment is hovering around 5.9 percent and has gone up slightly as the summer has progressed. This raises the question of how many of the formerly employed are now in the gig economy, skewing the figures.

We are in what is, in effect, a post-war recovery. Traditionally, that is a time for social readjustment, for old bonds to be loosed, and for new energy to be released. Is it time to sack the boss?

Llewellyn King is executive producer and host of White House Chronicle, on PBS. His email is llewellynking1@gmail.com and he’s based in Rhode Island and Washington, D.C.

Web site: whchronicle.com

Llewellyn King: Welcome to summer -- the American season

Old Orchard Beach, in Maine

WEST WARWICK, R.I.

The calendar opines that summer starts on June 20, but we know better. Metaphorically, it starts on Memorial Day, when we give thanks to those we honor, those who gave their lives for their country. Then it is, “Beach, ahoy!”

Memorial Day weekend signals the beginning of summer as if a flaming taper were applied to black powder and a cannon fired, joyously marking the sun’s reascendance to its throne.

Summer is important everywhere: to the British who try to catch a few elusive rays under their perfidious sun; to the French who shut their country down in August, and claim their spots on the crowded Mediterranean and Atlantic beaches; or to the Germans who take the summer break as a time to earn bragging rights on how far away and in which unlikely places they took their generous six weeks of vacation.

It isn’t that we Americans don’t travel. But it is here, at home, that we worship summer with the adulation of the sun. It is here we celebrate warmth, sand, water and barbecues. It is here that summer is most adored, most longed for, and most remembered for everything from young love to wraparound family togetherness.

All the world celebrates summer, but Americans exalt in it; treasure it as no others around the world.

Summer is woven into our culture, from those beach movies of the 1950s to its endless evocation in popular songs.

Growing up in Africa, I was bemused and confused by all of this summer worship coming out of the radio. We took summer for granted. It incorporated our rainy season and was a little less lovely than winter -- when the weather was so fair that the radio station (there was but one, and no television station ) didn’t announce the weather for six months. How many ways can a weather forecaster, even the most creative, say “perfect”?

Yes, on the Zimbabwe plateau (highveld), close to the equator, the weather is perfect and, if I might say so, perfectly boring.

No, give me the change of season. Let me join other Americans in celebrating the euphoria that breaks out every June when we say goodbye to dull care and embrace the bounty of summer, of cookouts and hikes, of shorts and tank tops and of going sockless.

From the beaches to the lakes, summer draws us to the water; some just want to bake their winter-ravaged bodies in the hot sand, others want to take to the water in or on everything from canoes to paddle boards, and from dinghies to great schooners.

The call of the water is loud in summer for many Americans but so, too, is the call of the mountains, and the glory of the National Parks beckons with a seductive finger.

The American summer is inextricably tied up with coming of age, of first love – indeed, the first of many first things. But it also enchants the oldsters. It is the time for family integration, when grandchildren and even great-grandchildren can be indulged from Portland, Maine, to Myrtle Beach, South Carolina, and from the Upper Michigan Peninsula to San Diego.

Summer thrills, stocks the memory bank, as even Alaska turns from the epitome of winter to a lush and tempting land where the outdoors offer a cornucopia of joys.

I have been lucky enough to spend summers around the world, so I can report that nowhere is summer embraced with such near-religious fervor as it is here in the United States; nowhere is the sun’s return to full raiment of majesty so celebrated and adored.

Remember this Memorial Day those who fell so that we might be free to fire up the grill and soak up the sun. It shines so lovingly on America.

Llewellyn King is executive producer and host of White House Chronicle, on PBS. His email is llewellynking1@gmail.com and he’s based in Rhode Island and Washington, D.C.

Linda Gasparello

Co-host and Producer

"White House Chronicle" on PBS

Mobile: (202) 441-2703

Website: whchronicle.com

Llewellyn King: Where have all the restaurant workers gone?

The Union Oyster House in Boston, open to diners since 1826, is amongst the oldest operating restaurants in the United States of America, and the oldest that has been continuously operating (except for several months in 2020) since being opened.

WEST WARWICK, R.I.

The restaurants are back. Bravo! Across America, the restaurants are open or beginning to open. Cheers!

But there is something amiss. Something unexpected and as-yet-unexplained is going on: There is a national shortage of restaurant workers.

During the lockdown, I was among many who lamented the fate of those who prepped, cooked, served and cleaned up, enduring bad hours, difficult conditions and uncertain earnings.

However, there have always been those who want to work in restaurants. For some, such as college students, it is a way of earning on the journey to somewhere else. For others, and there are many, it is because they love the ethos of restaurant life: its people-intensity, and its real-time energy and urgency.

And for those who link ambition with acumen, restaurant work has always fostered the possibility of, as I have heard waiters say, “a place of my own.” Chez Moi beckons to those who would sell foie gras, as well as those who would sell hot dogs.

For unabashed entrepreneurs, it is probably impossible to beat restaurateurs. The chance of self-employment, to my mind, is the great motivation of the free-spirited. A food truck is a start and maybe enough.

We knew the pandemic would change things. But to change employment in the restaurant industry, even a reduced one? That isn’t only a puzzle, but also a hint of how the pandemic has altered things.

There are those in Congress and the state houses who hold that restaurant workers are lolling at home because they would rather collect unemployment benefits. But I doubt that there are hundreds of thousands of Americans who are so lazy, so work-averse that they would rather stay home -- after more than a year of staying home -- than returning to their restaurant jobs.

Something else is happening.

Horizons have changed, new jobs have been found, and the grueling but satisfying work of restaurants has given over to something else. After the plague, a new dawn.

The country is resetting, and lives are being reset, too. A waitress I know of in Florida found work in a print shop. She prefers the regular pay there to the uncertain income from waitressing. That is a reset in her life.

As we go forward, as the pandemic is less dominant in our lives, we are going to experience changes -- some anticipated, some surprising like the restaurant labor shortage.

We don’t know whether the full complement of workers will go back to their offices; we don’t know how schools will deal with the lost year; and we don’t know whether the mini migration from town to country that has been a feature of the last year is a trend to stay or a product of panic.

What we do know and rejoice in is that we can go back to being restaurant patrons. In brief travels around New England, Washington, D.C. , and Ft. Lauderdale, Fla., I found that people are eating out with joy.

Restaurants are milestones of life. It is in them we celebrate birthdays and anniversaries, advance romance, or simply eat something that we wouldn’t get at home.

But that isn’t all. Restaurants, however modest, are destinations. During this long pandemic, we have missed having a destination.

Restaurants in all societies are part of the fabric of how we live. Eating out is woven into our lives, whether it is a humble hamburger or a great ethnic food feast. The first step in the American Dream for many immigrant families is to start a restaurant, to employ the social capital that they brought with them: their cuisine.

Bon appétit! We need restaurants because, in their great variety, they add spice to our lives, especially after the long lockdown.

Llewellyn King is executive producer and host of White House Chronicle, on PBS. His email is llewellynking1@gmail.com and he’s based in Rhode Island and Rhode Island.

Web site: whchronicle.com

Llewellyn King: The unfair social pressure to get a college degree

Corpus Christi College, part of the University of Cambridge

WEST WARWICK, R.I.

In case you don’t know, it is, the White House has announced, Older Americans Month.

They say, in the newspaper game, “Write what you know.” I find I know about being “older.” That sounds just a bit kinder than the bald “old.”

Chalmers M. Roberts wrote a wonderful book called How Did I Get Here So Fast?: Rhetorical Questions and Available Answers from a Long and Happy Life. Quite so.