Will it into order

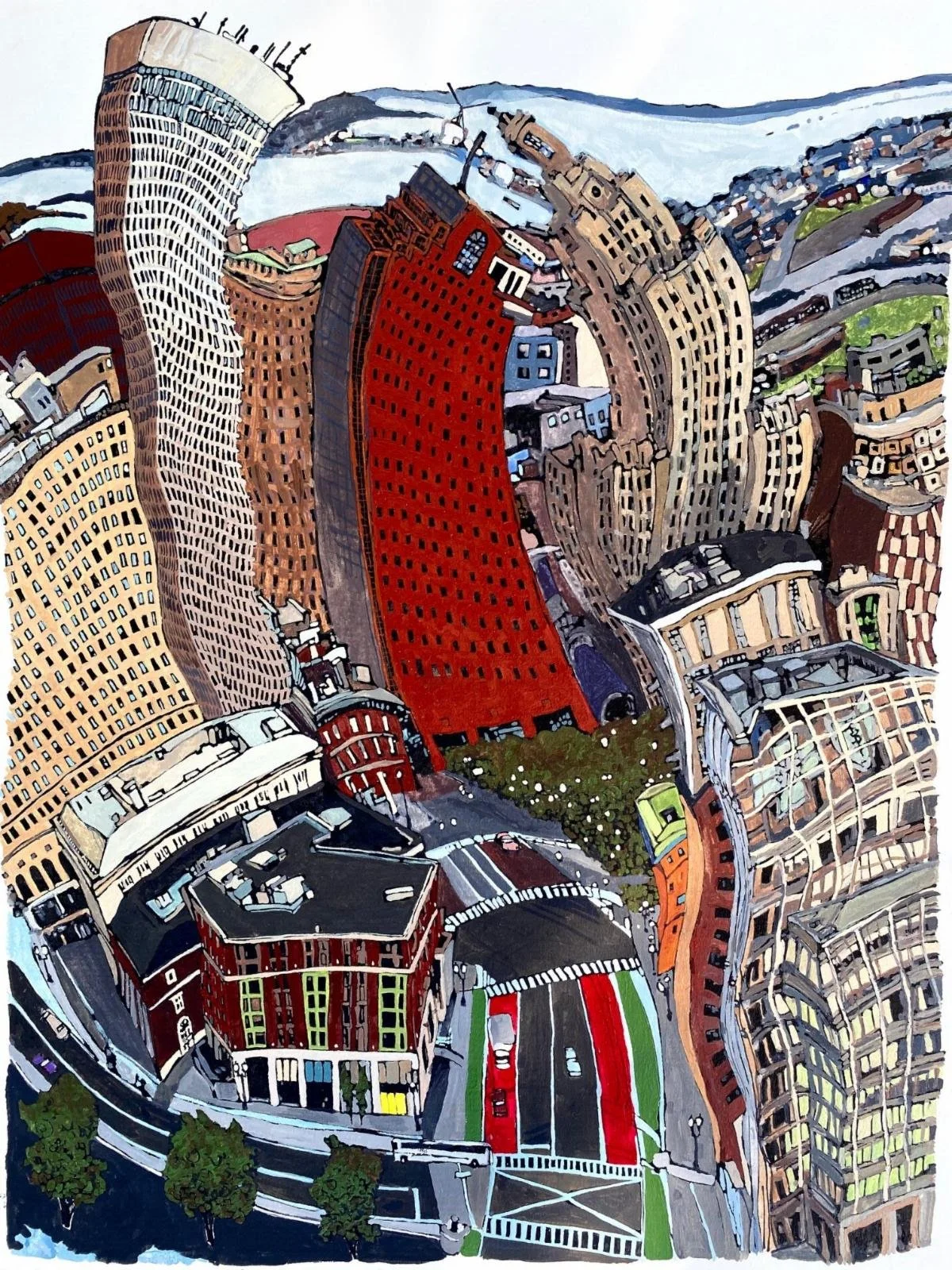

“I'm a Mess” (mixed media on canvas), by Sonja Czekalski, in her joint show, “Body/Image,” with Tracy Wesisman, at Hera Gallery, Wakefield, R.I., through Oct 8.

For more information, hit this link.

The Gallery says:

“These two, concurrent solo exhibits explore ‘changing body and societal expectations’ and ‘womanhood and women’s bodies through the female gaze.’ Both women's work, from Weisman's fiber and mixed-media pieces to Czekalski's mixed-media and sculptural assemblages interrogate society and culture from a woman's point of view.’’

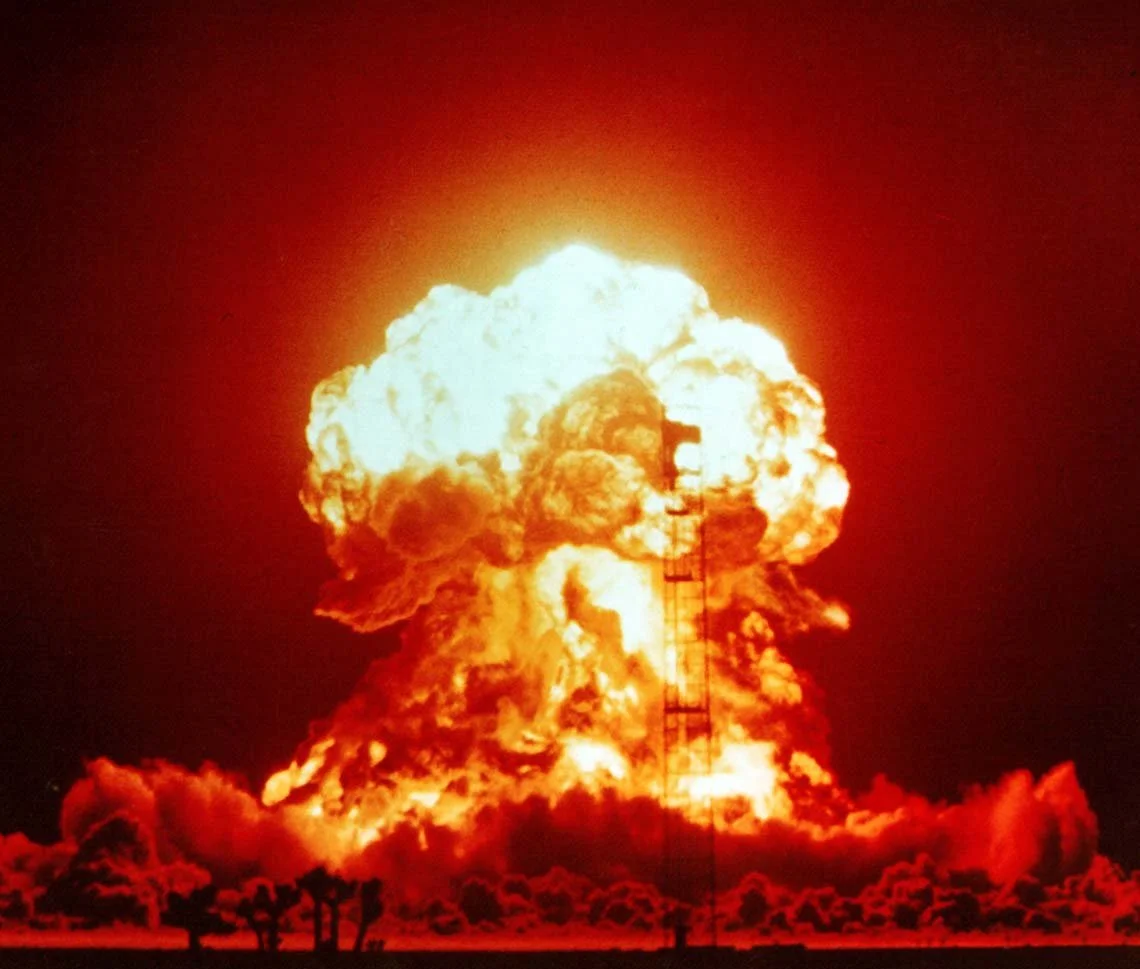

The Bell Block in Wakefield, in “South County, R.I.

— Photo JacobKlinger

Same places, different scenes

Harry Adler travels every morning as dark yields to dawn. He’s always on foot, running through Pawtuxet Village (straddling Cranston and Warwick, R.I.), where he lives. Along the way, he photographs that day’s magnificence.

Deep blue cove water melding into powder-blue sky. Snow frosting feathered reeds. Geese with orange feet waddling up a boat ramp. Trees mirror-imaged in the silvery Pawtuxet River. Historic houses in silhouette.

Adler began posting his village photos on Facebook and Instagram three years ago, and more so since the COVID pandemic erupted. Legions of admirers recognize his talent.

“The eye of the morning is winking at you,” writes one Facebook friend of a sunrise photo. “Your eye sees things that most don’t,” writes another. Many thank Adler for brightening their mornings and sparing them from waking up when he does – at 4:13 a.m. (in time to feed the five cats and run three to five miles).

Adler’s photographs will be displayed at “Traveling in Place,” an exhibit at the Aspray Boat House, 2 East View St., Warwick, R.I., in partnership with The Edgewood Village. Friends, including artist Bert Crenca, suggested that Adler exhibit his work: Adler agreed so long as part of the proceeds go to The Village Common of Rhode Island.

The exhibit’s title stems from Adler’s observation: “When I started running in the Pawtuxet Village area, I was noticing that every day was dramatically different. And that became the thought behind ‘Traveling in Place.’ I’m still in the same place, but feel like I’m traveling because I’m not seeing the same things all the time. Each day is brand new.’’

Adler, co-owner of Adler’s Design Center & Hardware, on Wickenden Street in Providence, is familiar to many Rhode Islanders. Customers know him as the pleasant font-of-knowledge guy behind the paint counter.

Adler sets out just after 6 a.m. from the 1857 Greek Revival house he owns with his partner, Suzy Box. He runs while searching the skies and scoping out the light. If the light is right, he clicks the shutter on his IPhone 12 Pro.

He shoots his images from the same spots at the Pawtuxet Cove Marina, Stillhouse Cove and the Rhode Island Yacht Club -- same locales but ever-changing beauty.

Opening reception and “Meet the Artist” on Saturday, Sept. 17, at 5 to 8 p.m. Show continues Sunday, Sept. 18, at 12-3 p.m. Refreshments, live music and free parking. For more information, please contact Sorrel Devine at eirehead1@gmail.com

Llewellyn King: Uberizing your solar-paneled roof

WEST WARWICK, R.I.

The Uber model is changing America. First it made a business out of the family car. Then it made a business out of the spare room or vacation house.

Soon it might make a business out of the roof over your head.

That is the dream of a group of hugely successful entrepreneurs who see roofs as the next big monetization of a widely held capital asset.

This group, which at present chooses to remain anonymous, believes that with the right communications network and smart computer linkage, the nation’s sun-trapping roofs could become a new source of electricity and, if connected to in-home batteries, a virtual power plant of scale and reliability.

What Uber did for ride sharing and what Airbnb did for lodging, these entrepreneurs believe could be done for the electric-utility industry.

One of them told me, “A network can be many different things, but in the context of a network of potentially millions of solar rooftops, it means virtually real-time capture and analysis of billions of data points. Only a wireless network, using the latest broadband technologies – similar to those that support our smart phones – can handle that workload.”

Rewind the clock to when solar cells became generally available: Utilities encouraged their use and bought electricity from customers when it was generated, not when it was needed.

At the same time large solar plants began to be developed and owned by the utilities, which worked better for them, and they soured on rooftop solar.

In talking to utilities, I find them to be cool-to-indifferent to rooftop solar but enthusiastic about solar central station generation, particularly if linked with battery storage. Mostly, utilities like solar generation because of its predictability.

The idea of hooking together a vast network of millions of solar panels on roofs with their own batteries puts demand back in the hands of the utilities, giving them the flexibility of having a great new resource.

Also, like the Uber model, there would be variable pricing: In a crisis or a high-demand situation, the utility or the system operator would order power from homeowner batteries at surge prices, befitting all. Owners of solar rooftop and battery setups would become “citizen solarizers.”

The concept of a vast, on-demand, virtual power plant isn’t entirely speculative. Brian Keane, president of SmartPower, told me that what might be a frontrunner is already being tested in Connecticut.

“All residential customers who choose the ‘Connecticut Green Bank’s CT Storage Solution’ option receive the generous, upfront rebate incentives for agreeing to have their battery drawn from every weekday afternoon during June, July, and August, as well as on high-need 'critical’ days on the weekends, in September, and for a handful of days during the winter months. Customers will get a payment each year based on the amount of electricity that is drawn from the battery,” Keane explained.

The development of a national virtual power system would enhance something that is happening quietly, which is what I call the “buttressing of the grid.”

It is what might be seen as the tacit acceptance that the grid isn’t going to be rebuilt in any substantial way, but it will be buttressed by new generation and limited new transmission. Uberizing rooftop solar could be an important part of this buttressing – and a gift to the nation both as a source of clean power and citizen involvement.

It remains to be seen whether regional solar networks would be subject to regulation by the federal government or by the states.

Going forward, a rooftop solar installation might be more than a convenience for a household, and a way of signaling green virtue.

Llewellyn King is executive producer and host of White House Chronicle, on PBS. His email is llewellynking1@gmail.com and he’s based in Rhode Island and Washington, D.C.

Llewellyn King: Wireless charging on a huge scale a Holy Grail of EV world

The primary coil in the charger induces a current in the secondary coil in the device being charged.

WEST WARWICK, R.I.

It is a dream still associated with the Serbian-American inventor Nikola Tesla: broadcasting electricity, making it available to users without a wire.

Tesla took his plans for sending electricity through the air to the grave with him, having been one of the architects of alternating current which was the building block of the electrified world.

But Tesla’s dream has never died and, in fact, is alive and well and making progress -- although not on the universal scale envisioned by Tesla or his followers, who look on his scheme for electricity broadcast from towers, like radio, as a Holy Grail.

His dream was as improbable as it was alluring.

But on a more down-to-earth level, inductive charging – wireless power transfer -- is surging. It has two distinct visions: One is to make wireless charging a reality for small devices. If airport terminals were wired for charging as they are for WiFi, there would be no more sitting on the floor by a plug. The other is for electric vehicles.

Ahmad Glover, the enthusiastic president of WiGL, a small wireless electric transmission company, told me the military is extremely interested in wireless charging. Glover, an Air Force veteran, said the goal is to have forward bases equipped, during operations and in warfighting situations, so that troops can charge their electronics without plugging in. “The less a soldier has to carry the better, “ he said.

Glover, who has worked with engineers from MIT and with Atlantic University, and has a contract with the Air Force, sees a day when charging is essentially automatic. The source of the power could be from a solar charger carried by a soldier in the battlefield rather than from the grid or the forward base generator. Glover believes the work he is doing will keep U.S. troops discreetly in touch wherever, whenever. He is working on beams and omnidirectional area chargers.

The big marquee application for wireless charging is in transportation. Here, most obviously, inductive charging has applications in public transport. The charger consists of an electromagnetic field radiating from a plate to a receiver under the vehicle. When the vehicle is positioned over the plate, charging takes place. This is known as a static system.

Mobile inductive charging, known as dynamic charging, where a moving vehicle can pick up a charge from the roadway, has been promoted overseas. But there is research money in the federal budget for inductive charging development in the United States.

The big advantage of static charging is that vehicles can be lighter and, therefore, cheaper. Taxis, trolleys, light rail, and buses could have smaller, lighter batteries as they will be charged regularly at predictable places, like traffic lights.

South Korea has been developing a charging system for buses where they get a charge every time they stop at a bus stop.

With abundant wind and hydro, Norway is headed for a carbon-free economy. By law, all new cars must be electric by 2025; accordingly, they are working to install inductive charging plates for taxis at their stands. A taxi driver will pull into a stand -- still common in Europe -- and while waiting for the next fare, the car will charge. If the taxi is on the stand long enough, it gets fully charged. Otherwise, it just gets a boost.

The advantages of inductive charging are multiple. First, batteries can be smaller and cheaper, and the vehicle lighter. For utilities, the load is spread over the day, coinciding with the abundance of solar generation.

The ultimate dynamic inductive dream is that cars will refuel as they speed down the highway. Italy has an experimental program installing charging coils in tarmac. Sweden is relatively far along with a similar experiment, and the United Kingdom is funding research.

Nikola Tesla’s dream is turning into reality.

Llewellyn King is executive producer and host of White House Chronicle, on PBS. His email is llewellynking1@gmail.com and he’s based in Rhode Island and Washington, D.C.

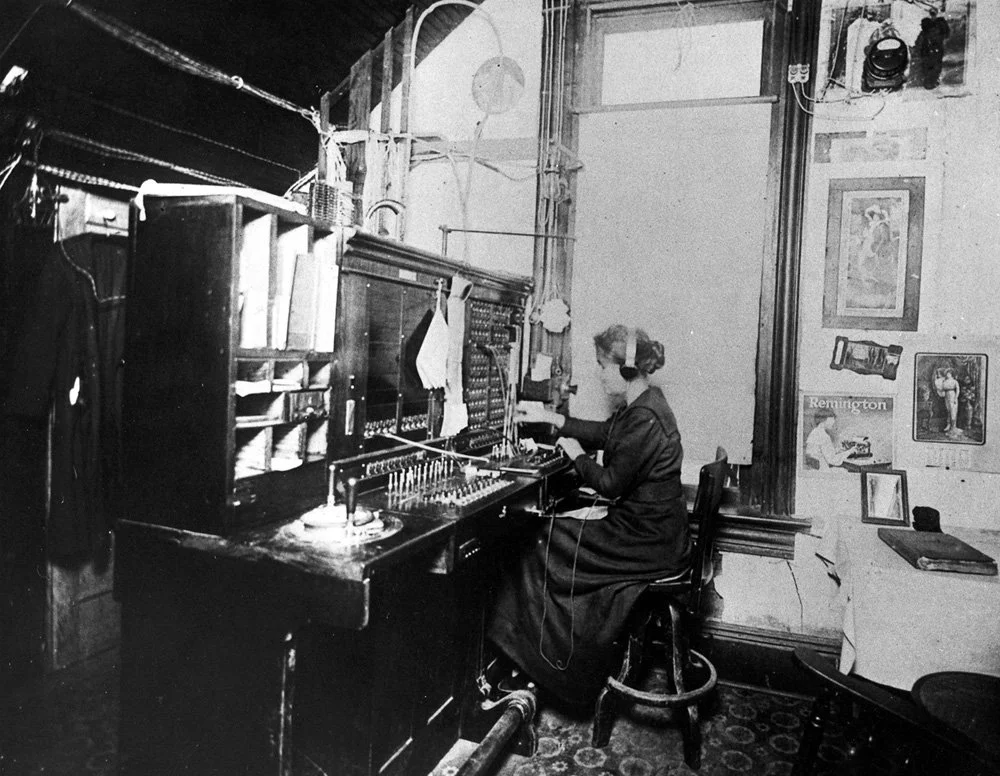

Llewellyn King: The thrill of getting a human on the line; the ‘service economy’ is a giant con

Telephone operator circa 1900.

WEST WARWICK, R.I.

Something wonderful happened to me this week. I spoke on the telephone to a human being at a credit-card company. Well, not immediately. That would be too much to expect.

I had to go through some of the hoops of the company’s automated phone system, beginning with (as it always seems to) “Listen carefully because our menu has changed.”

And, of course, I had to enter the card number, the PIN, the last four digits of my Social Security number and my maternal grandmother’s name, and learn that for quality purposes my rising frustration was being recorded.

I explained repeatedly to the recording what I needed. It wasn’t having any of it. If it was a sample of artificial intelligence, it was acting more like artificial stupidity.

Finally, the AI device decided that stupid people – me -- weren’t worthy of its recorded messages and transferred me to a “representative.” Banks, credit- card companies, and insurance offices don’t have people; they have “representatives.”

This representative was smiley-voiced and delightful. She also was human. After 20 awful minutes of hearing a recorded voice (“How can I help you? I did not get that. Push 7.”), here was someone who really wanted to help. Hallelujah!

Try talking to a live person, you will like it. It is wonderful. She told me about the weather where she was, San Antonio, and we had a whale of a time doing something that I forgot people can do with a telephone: small talk. In a trice, she took care of my need.

I am a regular panelist on a weekly Texas State University webinar. A super-smart man, a polymath, suggested there that my problem for not reveling in the new isolation -- working from home, talking to machines, sending texts, rather than speaking on the telephone and emailing -- may be generational. This I take to be a nice way of saying that if people had sell-by dates, I am past mine.

The implication is that there is a superior place where the digital people do digital things, and pity those of us who do not do digital things, like eat, drink, fall in love. No less a person than the actor Meryl Streep said, “Everything that truly makes us happy is quite simple: love, sex and food.” If she likes talking, too, I will award her my personal Oscar. Another endearing Meryl quote is, “Instant gratification is not fast enough,”

There is one place where computers have not infringed on the old way of doing things: The U.S. Department of State. I believe that they are still looking up things in giant ledgers and writing by hand on parchment.

I say this because if you, dear citizen, wish to get a passport renewed, the expedited route at your local passport office takes five to seven weeks. I am waiting in apprehension for my renewal, having paid $200 for the super-slow “expedited service.”

You can get a replacement Social Security card in moments, a driver’s license immediately, but the State Department will have none of that.

Oddly, passports are issued to all except those with unpaid child support or outstanding criminal warrants. There are more reasons to deny a driver’s license than a passport. But the wheels at the State Department grind extremely slowly, and time isn't an issue.

The service economy has been a giant con, dreamed up by MBAs to keep customers at a distance or to dehumanize them so that they forget that they pay for the abuse they receive, whether it is from the passport office or some financial institution.

I frequent one gas station, in Scituate, R.I., where they still pump your gas. Night and day, there are lines of motorists waiting for fill-ups, and to have a few cheery words with the pump jockeys. Human contact, real service, seems to be worth a few cents more a gallon.

Llewellyn King is executive producer and host of White House Chronicle, on PBS. His email is llewellynking1@gmail.com, and he’s based in Rhode Island and Washington, D.C.

Hope Dam on the Pawtuxet River in Scituate

Llewellyn King: Why I love America but fear its political decay and paralysis

Fourth of July fireworks in America's easternmost town, Lubec, Maine, population 1,300. Canada is across the channel to the right.

— Photo by it'sOnlyMakeBelieve

WEST WARWICK, R.I.

Martin Walker, the gifted former Washington correspondent of The Guardian, used to start his speeches by saying that the Fourth of July wasn’t a time for sorrow for him because it was a time when good British yeomen farmers in the American colonies revolted against a German king and his German mercenaries.

Walker — who now lives in France and writes the hugely successful “Bruno” detective books set in the Perigord region — once told me, “It’s exciting living in a country where the president can order up an aircraft carrier to settle a dispute.”

He, an Englishman, and I, a former British colonial (from Zimbabwe) who moved here in 1963, shared our admiration for the United States. For America’s birthday this year, I have counted some things I most like and admire about this country of endless experimentation. Also, alas, I admit that it is getting harder to feel as proud of it as I once did.

America, for me, has always embodied a special freedom: the freedom to try. The wonderful thing about it is that you can try a business, an idea, a way of living, or even a way of thinking. I read in The Waist-High Culture, the 1958 book by Thomas Griffith, that Europe was a “no” culture and the United States was a “yes” culture. So true.

In my first year here, I wrote to a family member in England, marveling at the size and scope of the American market. I wrote to her, “You could make a fortune here making glass beads, so long as they were good glass beads.” I still believe that.

The other great freedom, which I treasure, is that you can move across the country and start all over again. If you feel you have failed in New York, you can take a fresh sheet and try again in Chicago, Austin or San Francisco. You can have failed in marriage, in business, in a career, and in some very public way, but you can go on anew somewhere else.

You can’t do that in what are, in many ways, city-states — for example, in the way England is dominated by London and France by Paris. There is geographic freedom in the United States that has an exhilaration all its own.

I was intoxicated by America from the first. I didn’t dwell on the sins of the past, from the cruelty of the Puritans, the pioneers and the planters to the folly of Prohibition. When I arrived, I embraced all that was in the present; the civil-rights movement was underway and gathering strength, and it was possible to believe that the United States would continue to be the shining example of how you get it right, how you correct big and small errors, and how you let people prosper. John F. Kennedy was president, and it was a new day.

When I covered Congress, I was enchanted with it: the committee power centers, the indifference to party discipline, and a system where you really did need majority approval to get a law passed.

Overall, members of Congress were among the hardest-working (and some were the hardest-drinking) around. They sought to understand issues from atomic energy to cancer. Congress wasn’t perfect, but it aspired to get things right.

For many years, I participated in the Humbert Summer School — a think tank — in the west of Ireland. I used to enjoy talking up the presidential system as superior to the parliamentary one, where a simple majority can wreak havoc.

Now, alas, Congress is experiencing the evils of parliamentary government and none of the virtues, particularly swift legislating. Party discipline — as in the case of House Minority Leader Kevin McCarthy, of California, shunning Rep. Liz Cheney, of Wyoming — has supplanted the old tolerance for differences within the party. It began with the 1994 Gingrich Revolution, abetted by the proliferation of single-point-of-view talk radio.

Like all unchecked decay, it has gotten worse.

America the Beautiful, I wish you a happy birthday. I thank you for your generosity over these decades, and I say sincerely, “Mind how you go.” The world needs your seeking to be fair and just, and full of possibility, not divided and rancorous, and a threat to yourself.

Llewellyn King is executive producer and host of White House Chronicle, on PBS. He’s based in Rhode Island and Washington.

Solar arrays and trees

On roofs when possible.

Adapted from Robert Whitcomb’s “Digital Diary,’’ in GoLocal24.com

Inevitably, some residents of New England suburban or exurban areas are duking it out with solar-energy developers. The residents complain that too much open land and woods are being taken for the solar arrays near them. Two recent hot spots for these fights are Johnston, R.I., and cranberry-bog country in Wareham and Carver, Mass.

Well, the world is heating up and the more renewables we use the worse it is for such murderous petrostate dictators as Vladimir Putin. And bear in mind that much land being eyed for solar arrays might instead be turned into housing projects if the solar is blocked. Most locals would probably hate that even more than “solar farms,’’ in part because local property taxes would have to go up to pay for public services.

The saddest thing in this is cutting down woods to make way for the arrays. Of course, trees are huge absorbers of the carbon dioxide spewed out by our burning fossil fuel. But putting up solar arrays more than makes up for the loss of the equivalent space in woodland in terms of CO2 control, at least given current and projected technology and (wasteful!) electricity use. (The Ukraine war and the energy crisis it has caused is speeding renewable-energy research and development.)

John Reilly, co-director of MIT's program on the science and policy of global change, estimated for WGBH how much power would be generated if about 2.5 acres were clear cut to put up solar panels. WGBH reported: “He figured out you’d make up for all the carbon stored in those trees in just 46 days, if you were preventing that same amount of energy from being generated by carbon-emitting coal, or 23 days, if you were offsetting natural gas.’’

He said: “’There is a carbon loss from the trees, but it's made up fairly quickly. You're going to operate that solar panel for 20 years."’

Of course, the flora and fauna in woods should be protected as much as possible amidst the urgent need for us to burn much less natural gas and oil. Still, there’s a little bit of irony here. Much of the woodland that neighbors are trying to protect was open farmland in the early and mid 19th Century, before competition from Midwest farms and the rise of manufacturing in New England drew most people off the farms and the woods grew back. Take a look at some old pictures.

In any case, solar developers should make sure that there’s vegetation (to give off oxygen and provide a bit of ecosystem for birds and animals) under the arrays and not just barren dirt. And hire goats to keep it from getting too high?

There will be painful, or at least inconvenient tradeoffs as we wean ourselves off the still necessary poison that is fossil fuel.

We certainly could do much more to minimize the aesthetic pain of some neighbors by putting solar panels on many more buildings large and small instead of on land. Use, for example, those vacant parking lots at dead malls and elsewhere for solar arrays, while waiting for new clean-energy sources, be it hydrogen, fusion or something else to come on line. There’s probably a recession coming soon, slowing building construction and cooling property-price inflation. Take advantage of that to take more vacant urban and suburban land for solar?

Hit this link for the WGBH trees vs. solar story.

More trees now.

Note the open land.

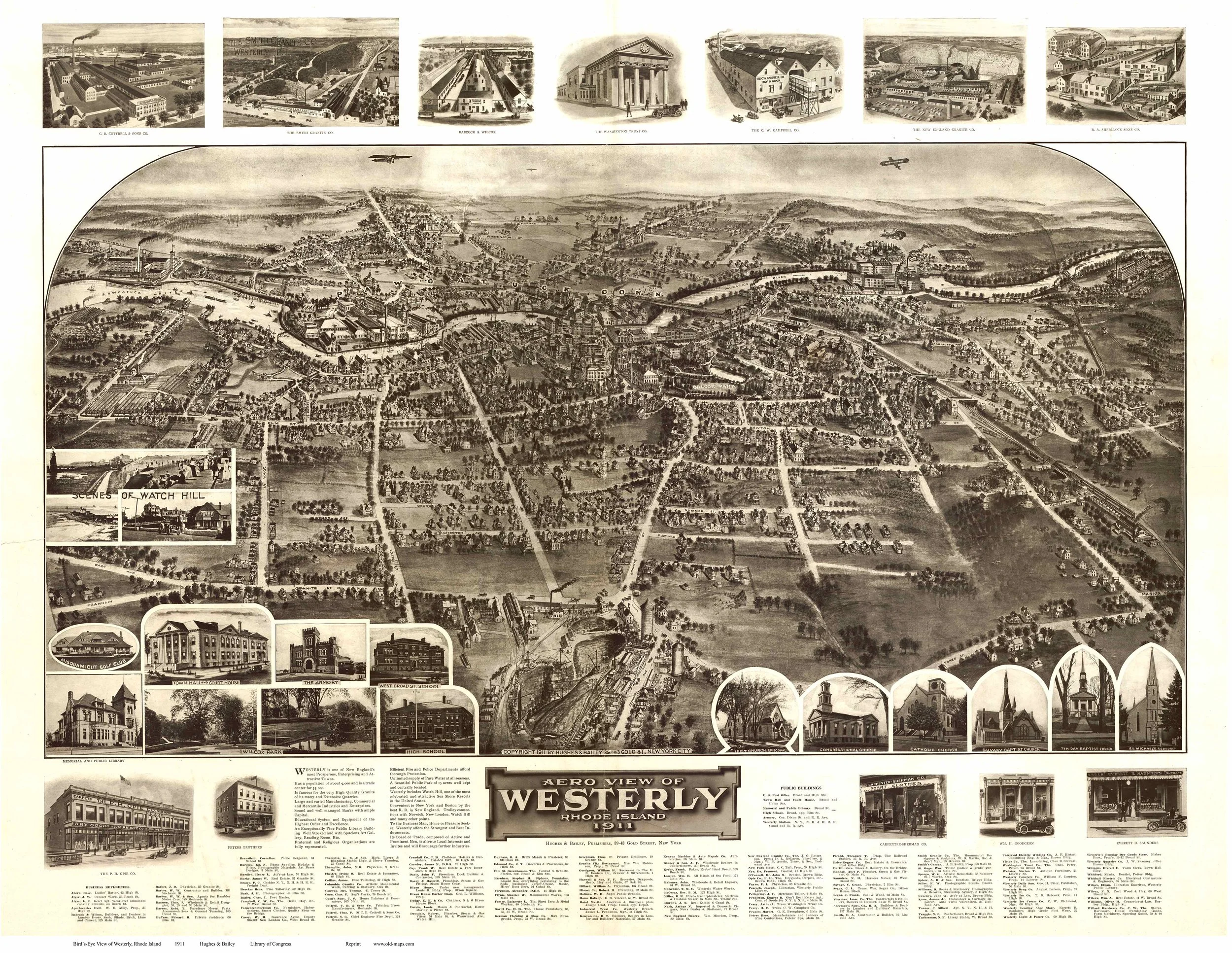

Fascinating, complicated and scandal-rich Newport

President Chester Arthur tips his hat while vacationing in Newport in 1884. The city has drawn many celebrities each year in the summer since the Civil War.

Adapted from Robert Whitcomb’s “Digital Diary,’’ in GoLocal24.com

The drive to Newport from Providence via Fall River has some dramatic stretches. The Spindle City rises up, with its beautiful old stone mill buildings, looking a bit like an English provincial city and, if you carefully crane your neck on the Braga Bridge, the view down Mt. Hope Bay is spectacular, as is, further south, the view from the Sakonnet River Bridge. If only they could clean up Middletown’s hideous West Main Road commercial strip, which mars the approach to Newport. More trees would help, as would some targeted demolitions.

Then you get into Newport, one of the country’s most interesting cities – dense with class, ethnic, economic, cultural and architectural complexity. Rich, poor, Navy people, current and former spies, engineers, socialites, TV celebrities, etc., etc., and some of the best gossip in the world, enriched with scandals, present and past. Among the most famous:

The late Claus von Bulow’s alleged attempted murder of his late utility heiress wife, Martha “Sunny’’ von Bulow, which led to two sensational trials in the ’80’s (and the movie Reversal of Fortune, a sort of dark comedy) and the late tobacco heiress Doris Duke’s apparent murder (by driving into him at her Newport estate, Rough Point) of an assistant, Eduardo Tirella, in 1966. Some Newporters connected to the city’s upper crust who knew these characters and those around them still talk about these cases, as I discovered last week at a lunch in the City by the Sea.

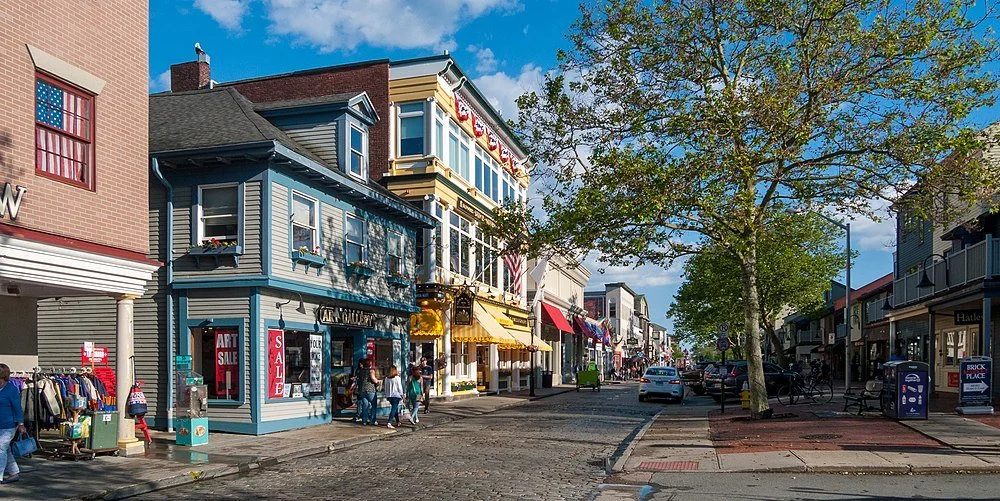

Thames Street, on Newport’s waterfront. In high summer, the street is often mobbed with shop patrons, restaurant and bar goers and just plain tourist/gawkers. Some are sober.

Cynthia Drummond: Global warming sends a toxic worm to southern New England

Model of a Hammerhead worm.

And a real one.

— Photo by SREEJITH VISWANATHAN

From ecoRI News (ecori.org)

HARRISVILLE, R.I.

Samantha Young was working in her father’s garden when she saw some strange-looking worms she hadn’t noticed before. What she had found were invasive hammerhead worms.

“The three Hammerhead Worms were all found in my dad’s yard on Round Top [Road] in Harrisville,” she wrote in an email. “I found them while cleaning up around the yard. They were all found underneath stuff like buckets, and rocks.”

Native to Asia and Madagascar, the Hammerhead Worm, or Bipalium Kewense, was transported to Europe and the United States in shipments of exotic plants. It has been in the United States since the early 1900s and is most commonly found in states such as Louisiana, where conditions are warm and humid. But now, as the climate warms, these invasive worms are spreading.

With their distinctive heads and long, flat bodies, hammerhead worms, which are members of a large family of flatworms, or planaria, are easy to identify. They are usually striped, and can grow in length to nearly a foot.

The biggest concern is the damage the carnivorous worms could do to agriculture, because they are predators of earthworms. While the glaciers killed almost all the native earthworms north of Pennsylvania, and most of the earthworm species in the United States were brought here by European settlers, earthworms are important for soil health.

The one thing you don’t want to do if you find a hammerhead worm is touch it, or let your pets, including backyard chickens, eat it.

Hammerhead Worms produce a neurotoxin, tetrodotoxin, which is also found in puffer fish, which are sometimes served in sushi restaurants as “fugu sashi,” where they are prepared by only the most highly skilled chefs.

Josef Görres, formerly of the University of Rhode Island, currently teaches soil science at the University of Vermont and is familiar with hammerhead worms.

“If you read some publications out of Texas, they’re kind of saying, ‘Hey you know, there are really big ones,’ of course, in Texas, they always have bigger things than anybody else, but they’re saying it may actually be a human health concern,” Görres said. “Most of that toxin is near the surface of the worm so you touch it or you play with it, or something like that, it might cause you harm.”

As if toxins weren’t enough, Hammerhead Worms can also transmit harmful parasites to humans and animals. And they have another unpleasant characteristic: they regenerate from segments if they are cut up, so chopping them into pieces will only make more.

Görres said these invasive worms weren’t considered a threat until they began to expand their range.

“On first introduction, there probably weren’t many of them and so now, as they’re spreading, they’re becoming more obvious to people,” he said. “I, certainly, over the last five years, have seen a lot more than even 10 years ago.”

Young said she had to research the three worms she found to identify them.

“I didn’t know what they were until I googled it,” she said. “I left them in a Tupperware container until they died.”

If people can’t handle the worms without protection and they can’t cut them up, what is the most efficient way to kill them? Görres recommends salting, bagging and freezing.

“I read somewhere that in order to kill them, you put them in a bag, you put salt in there and then you freeze them for 48 hours,” he said. “Double overkill. The salt will desiccate them and then freezing them, if anything is left, freezing them will also kill them — 48 hours at minus 20 degrees Celsius, which is what the freezer is at, usually.”

Since they are not perceived as a threat to agricultural crops, Hammerhead Worm research is not well-funded. Concern has instead focused on another invasive species from Asia, the Snake Worm, which devours the surface material or “duff” of the forest floor.

“They consume the forest floor, the duff layer and … by the time all that duff layer is gone, there’s a lot fewer plants in the understory of the forest,” Görres said.

The ecological damage caused by Hammerhead Worms, he said, is minor by comparison, at least so far.

“I am not really 100 percent concerned about them,” he said. “It’s just something I keep on my radar, because they’ve been reported in the Northeast now for a few years and I keep finding them in various places, woodlands as well as gardens.”

Görres also noted dry summers, which are becoming increasingly common in New England, might limit the spread of Hammerhead Worms, which need humidity to thrive.

“Things are getting dryer here,” he said. “They might just be confined to wetlands and areas where people irrigate.”

Cynthia Drummond is an ecoRI News contributor.

In exurban Harrisville, R.I.

—Photo by User:Magicpiano

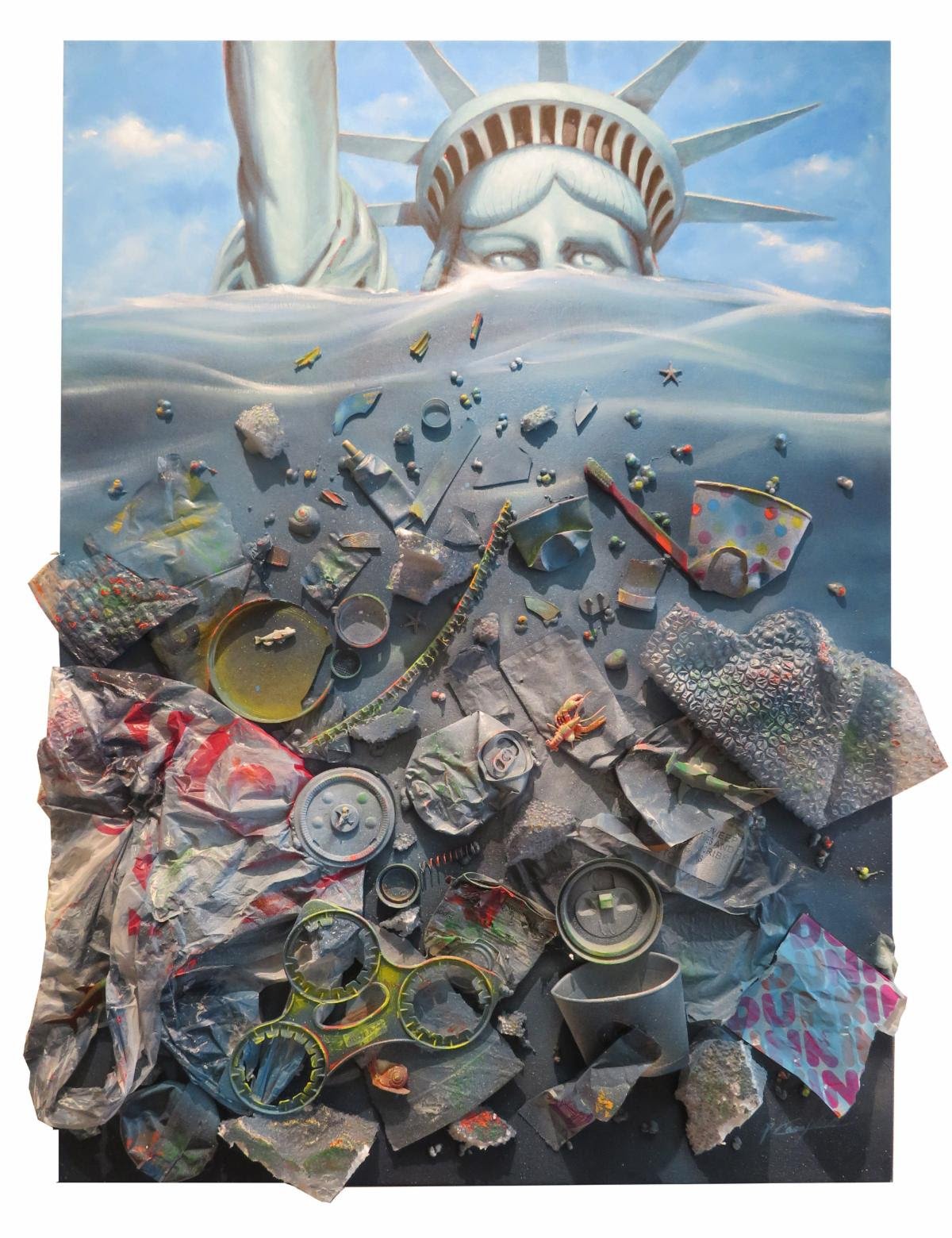

Some detritus of commercial civilization

Painting by Lincoln, R.I.-based artist Peter Campbell in his show through June 24 at Gallery 175, Pawtucket, R.I.

The Eleazar Arnold House (built in 1693), in Lincoln, R.I., is a rare surviving example of a stone-ender, a once-common building type in New England featuring a massive chimney end wall. The houses stone work reflects the origins and skills of settlers who emigrated to New England from southwest England, and it’s a National Historic Landmark.

Llewellyn King: For society’s sake, newspapers, whose work is looted by tech firms, deserve a reprieve

WEST WARWICK, R.I.

Newspapers are on death row. The once great provincial newspapers of this country, indeed of many countries, often look like pamphlets. Others have already been executed by the market.

The cause is simple enough: Disrupting technology in the form of the Internet has lured away most of their advertising revenue. To make up the shortfall, publishers have been forced to push up the cover price to astronomical highs, driving away readers.

One city newspaper used to sell 200,000 copies, but now sells less than 30,000 copies. I just bought said paper’s Sunday edition for $5. Newspapering is my lifelong trade and I might be expected to shell out that much for a single copy, but I wouldn’t expect it of the public to pay that — especially for a product that is a sliver of what it once was.

New media are taking on some of the role of the newspapers, but it isn’t the same. Traditionally, newspapers have had the time and other resources to do the job properly; to detach reporters to dig into the murky, or to demystify the complicated; to operate foreign bureaus; and to send writers to the ends of the earth. Also, they have had the space to publish the result.

More, newspapers have had something that radio, television and the Internet outlets haven’t had: durability.

I have a stake in radio and television, yet I still marvel at how newspaper stories endure; how long-lived newspaper coverage is compared with the other forms of media.

I get inquiries about what I wrote years ago. Someone will ask, for example, “Do you remember what you wrote in 1980 about oil supply?”

Newspaper coverage lasts. Nobody has ever asked me about something I said on radio or television more than a few weeks after the broadcast.

I was taken aback when, while I was testifying before the Senate Foreign Relations Committee decades ago, a senator asked me about an article I had written years earlier and forgotten. But he hadn’t and had a copy handy.

There is authority in the written word thay doesn’t extend to the broadcast word, and maybe not to the virtual word on the Internet in promising new forms of media like Axios.

If publishing were just another business – and it is a business — and it had reached the end of the line, like the telegram, I would say, “Out with the old and in with the new.” But when it comes to newspapers, it has yet to be proven that the new is doing the job once done by the old or if it can; if it can achieve durability and write the first page of history.

Since the first broadcasts, newspapers have been the feedstock of radio and television, whether in a small town or in a great metropolis. Television and radio have fed off the work of newspapers. Only occasionally is the flow reversed.

The Economist magazine asks whether Russians would have supported President Vladimir Putin’s invasion of Ukraine if they had had a free media and could have known what was going on; or whether the spread of COVID in China would have been so complete if free media had reported on it early, in the first throes of the pandemic?

The plight of the newspapers should be especially concerning at a time when we see democracy wobbling in many countries, and there are those who would shove it off-kilter even in the United States.

There are no easy ways to subsidize newspapers without taking away their independence and turning them into captive organs. Only one springs to mind, and that is the subsidy that the British press and wire services enjoyed for decades. It was a special, reduced cable rate for transmitting news, known as Commonwealth Cable Rate. It was a subsidy but a hands-off one.

Commonwealth Cable Rate was so effective that all American publications found ways to use it and enjoy the subsidy.

United Press International created a subsidiary, British United Press, which flowed huge volumes of cable traffic through London.

Time Inc. had a system in which their cable traffic was channeled through Montreal to take advantage of the exceptionally low, special rates in the British Commonwealth.

That is the kind of subsidy that newspapers might need. Of course, best of all, would be for the mighty tech companies to pay for the news they purloin and distribute; for the aggregators to respect the copyrights of the creators of the material they flash around the globe. That alone might save the newspapers, our endangered guardians.

Llewellyn King is executive producer and host of White House Chronicle, on PBS. His email is llewellynking1@gmail.com and he’s based in Rhode Island and Washington, D.C.

The wet look

Sunny day flooding in Miami during a “king tide’’.

Coastal flooding in Marblehead, Mass., during Superstorm Sandy on Oct. 2012.

Adapted from Robert Whitcomb’s “Digital Diary,’’ in GoLocal24.com

The stuff below is a heavily edited version of some of the remarks I made in a talk a couple of weeks ago and seem to me particularly resonant as we head into summer coastal vacation season:

Most of us are in denial or oblivious when it comes to sea-level rise caused by global warming. For example, Freddie Mac researchers have found that properties directly exposed to projected sea-level rise have generally gotten no price discount compared to those that aren’t, though that may be changing. And some states don’t require sellers to disclose past coastal floods affecting properties for sale. Politicians often try to block flood-plain designations because they naturally fear that they would depress real-estate values.

So the coast keeps getting more built up, including places that may be underwater in a few decades. It often seems that everyone wants to live along the water.

As the near-certainty of major sea-level rise becomes more integrated into the pricing calculations of the real-estate sector, some people of a certain age can get bargains on property as long as they realize that the property they want to buy might be uninhabitable in 20 years. Younger people, however, should seek higher ground if they want to live near the ocean for a long time.

A tricky thing is that real estate can’t just be abandoned—it must pass from one owner to another. Some local governments’ coastal permits require owners to pay to remove their structures when the average sea level rises to a certain point. Absent such requirements, many local governments’ budgets may not be enough to pay for demolition or the moving costs associated with inundation. There are some interesting liability issues here.

What to do?

Administrative mitigation would include raising federal flood-insurance rates and more frequently updating flood-projection maps. More localities can take stronger steps to ban or sharply limit new structures in flood-prone areas and/or order them removed from those areas. And, as implied above, they should implement flood-experience-and-projection disclosure requirements in sales documents.

As for physical answers to thwarting the worst effects of sea-level rise, especially in urban areas, many experts believe that some form of the Dutch polder approach, which integrates hard stone, concrete or even metal infrastructure, and soft nature-based infrastructure, along with dikes, drainage canals and pumps, may have to be applied in some low places, such as Miami and Boston’s Seaport District. Barrington and Warren, R.I., look like polder country.

Polders are large land-and-water areas, with thick water-absorbent vegetation, surrounded by dikes, where the ground elevation is below mean sea level and engineers control the water table within the polder.

Just hardening the immediate shoreline, and especially beaches, with such structures as stone embankments to try to keep out the water won’t work well. That just makes the water push the sand elsewhere and can dramatically increase shoreline erosion.

On the other hand, creating so-called horizontal levees – with a marshy or other soft buffering area backed with a hard surface -- can be a reasonable approach to reduce the impact of storms’ flooding on top of sea-level rise.

Certainly establishing marshes (and mangrove swamps in tropical and semi-tropical coastal communities) can reduce tidal flooding and the damage from storm waves, but that may be a political nonstarter in some fancy coastal summer- or winter-resort places. Then there’s putting more houses and even stores and other nonresidential buildings on stilts, though that often means keeping buildings where safety considerations would suggest that there shouldn’t be any structures, such as on many barrier beaches. Still, it would be amusing to see entire large towns on stilts. Good water views.

Oyster and other shellfish beds can be developed as (partly edible!) breakwaters. And laying down permeable road and parking lot pavements can help sop up the water that pours onto the land. I got interested in how shellfish beds can act as a brake on flood damage while editing a book about Maine aquaculture last year. Of course, the hilly coast of Maine provides many more opportunities to enjoy a water view even with sea-level rise while staying dry than does, say, South County’s barrier beaches.

In more and more places where sea-level rise has caused increasing ‘’sunny day flooding’’ -- i.e., without storms -- streets are being raised.

I’m afraid that, barring, say, a volcanic eruption that rapidly cools the earth, slowing the sea-level rise, the fact is that we’ll have to simply abandon much of our thickly developed immediate coastline and move our structures to higher ground.

Working-waterfront enterprises -- e.g., fishing and shipping -- must stay as close to the water as possible. But many houses, condos, hotels, resorts and so on can and should be moved in the next few years. If they don’t have to be on a low-lying shoreline, they shouldn’t be there as sea level rises. For that matter, entire large communities may have to be entirely abandoned to the sea even in the lifetime of some people here.

Coastal communities and property owners face hard choices: whether to try to hold back the rising ocean or to move to higher ground. Nothing can prevent this situation from being expensive and disruptive.

Common sense would suggest that we not build where it floods and that we should stop recycling flooded properties. Again, flood risks should be fully disclosed and we need to protect or restore ecologies, such as marshes, shellfish and coral reefs and dune grass, that reduce flooding and coastal erosion.

Nature wins in the end.

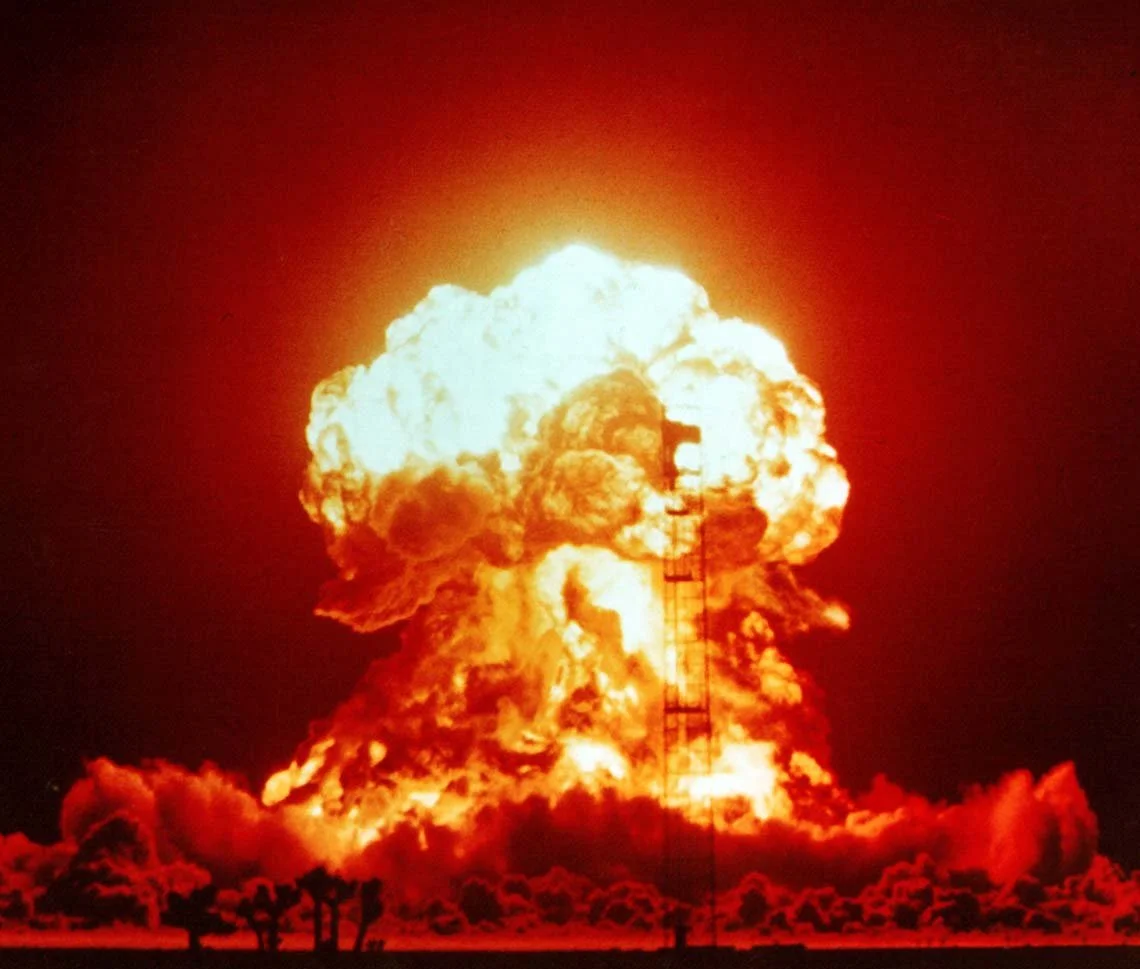

Llewellyn King: The threat of nuclear war and the license it has given Russia’s dictator

WEST WARWICK, R.I.

History isn’t short of people to blame. You could say of the present world crisis that it was former President Obama’s fault for not getting tougher with Russian President Putin in Syria. You could blame former President Trump for giving Putin a sense of entitlement and for undermining NATO, seeing it as a financial play. You could blame former German Chancellor Angela Merkel for encouraging Russian gas imports, shutting out the nuclear- energy option.

You could, of course, blame President Biden for explicitly telling Putin, and the world, what the United States wouldn’t do if he invaded Ukraine. And you could blame Biden and NATO for dribbling vital military aid to Ukraine over the first devastating weeks of the Russian invasion.

If you want to continue, you could blame the world’s military strategists for believing that Russia, after the fall of communism, had changed. You could, perhaps, blame NATO itself, for expanding its reach to the former Soviet republics of Estonia, Lithuania and Latvia.

But Putin is unequivocally the one to blame. The dictator is the one who wants to remake Russia in the image of the imperial tsars. It is a flawed scheme but a real one.

As the world grapples with the reality of Putin, the past informs but it doesn’t instruct.

If NATO were to engage Russia with conventional forces, it would triumph. That is one lesson of Ukraine. Russian military forces are woefully inefficient, even incompetent.

Would it were that simple.

The beast in the room, the feared monster, the threat that hangs over the whole world is nuclear war. It is the clear-and-present danger. It shapes our handling of Russia and will shape our response to China, if and when it invades Taiwan.

Nuclear-war avoidance is again dominating the world in ways we had nearly forgotten.

Will Russia, a caged, fierce bear, resort to nuclear, and how much nuclear to what effect against which targets?

The United States and the Soviet Union reached a modus vivendi: mutual assured destruction (MAD), which kept the peace even as nuclear armaments proliferated and stockpiles grew exponentially. Is that still the option? Is MAD -- so long after the collapse of the Soviet Union -- still the underlying realpolitik, the restraining factor between nuclear powers?

Does that mean that anyone with nuclear weapons can wage conventional warfare in the belief that they won’t face NATO or any other serious restraining military action because they can unleash terrifying global destruction?

Or is there, as some believe, the prospect of limited nuclear engagement, using area tactical nuclear weapons? This has never been tested.

There hasn’t been a limited nuclear ground war. Could it be contained? Should it be contemplated outside the deeper reaches of the defense establishment?

But it is what keeps the leaders of Europe, the United States and Canada awake nights. If you favor limited nuclear war, just look to the effects of a nuclear disaster, Chernobyl, and start multiplying.

It is the unthinkable scenario that must be thought about. It is the reality which holds back NATO and makes the West a spectator to the carnage in Ukraine.

Russia isn’t a rich country except in some natural resources. It has a large but poorly trained and equipped military. But it bristles with nuclear weapons aimed at North American and European cities. Its ability to threaten us with nuclear horror changes the balance between nations: an indelible change to future foreign policy.

In the short term, when contemplating the return of MAD in international relations, the question is: How mad – as in insane -- is Putin, and how ready is Biden?

The pieces on the world chess board have moved and they won’t be moved back. The intelligentsia has yet to grasp the extent to which Ukraine has changed the world – and made it a more dangerous place. They need to catch up fast.

Llewellyn King is executive producer and host of White House Chronicle, on PBS. His email is llewellynking1@gmail.com and he’s based in Rhode Island and Washington, D.C

Llewellyn King: The new normal will take time, not politics

WEST WARWICK, R.I.

Loud detonations are going off in the economy. When the debris settles, new realities will emerge. We won’t return to the status quo ante, although that is what politicians like to promise.

After great cataclysmic events — wars, natural disasters or the impact of new technologies — we need to acknowledge the realities and find the opportunities.

The inflation that is shaking the world is the inflammation that arises as markets seek equilibrium — as markets always do.

The greatest disrupter has been the COVID-19 pandemic, and the ramifications of how it has reshaped economies and societies are still evolving. For example, will we need as much office space as we did pre-pandemic? Is the delivery revolution the new normal?

Russia’s war in Ukraine has added to the pandemic-caused changes before they have fully played out. They, in turn, were playing out against the larger imperatives of climate change, and the sweeping adjustments that are underway to head off climate disaster.

Some political actions have exacerbated the turbulence of the economic situation, but they aren’t the root causes, just additional economic inflammation. These include former president Donald Trump’s tariffs and President Biden’s mindless moves against pipelines, followed by attempts to lower gasoline prices, or wean us from natural gas while supplying more natural gas to Europe.

In the energy crisis (read shortage) of the 1970s, I invited Norman Macrae, the late, great deputy editor of The Economist, to give a speech at the annual meeting of The Energy Daily, which I had created in 1973 — and which was then a kind of bible to those interested in energy and the crisis. Macrae, who had a profound influence in making The Economist a power in world thinking, shared a simple economic verity with the audience: “Llewellyn has invited me here to discuss the energy crisis. That is simple: the consumption will fall, and the supply will increase. Poof! End of crisis. Now, can we talk about something interesting?”

Of the many, many experts I have brought to podiums around the world, never has one been as warmly received as Macrae. Not only did the audience stand and applaud, but many also climbed on their chairs and applauded. I’m not sure Washington’s venerable Shoreham Hotel had ever seen anything like that, at least not at a business conference.

In today’s chaotic situation with political accusations clashing with supply realities, the temptation is to find a political fix while the markets seek out the new balance. Politicians want to be seen to do something, no matter what, and before it has been established what needs to be done.

An example of this was Biden increasing the allowed amount of ethanol derived from corn and added to gasoline. It is so small an addition that it won’t affect the price at the pump, but it might affect the price of meat at the supermarket. Corn is important in raising cattle and feeding large parts of the world.

There is a global grain crisis as a result of Russia’s war in Ukraine, which is a huge grain producer. Parts of the world, especially Africa, face starvation. The last thing that is needed is to sop up American grain production by burning it as gasoline.

We are, in the United States, gradually moving from fossil fuels to renewables, but this is going to move our dependence offshore, and has the chance of creating new cartels in precious metals and minerals.

Essential to this move is the lithium-ion battery, the heart of electric vehicles and battery storage for renewables, and its tenuous supply chain. Lithium has increased in price nearly 500 percent in one year. It is so in demand that Elon Musk has suggested he might get into the lithium mining business.

But lithium isn’t the only key material coming from often unstable countries: There is cobalt, mostly supplied from the Democratic Republic of the Congo; nickel, mostly sourced in Indonesia; and copper, where supply comes primarily from Chile.

Across the board, supplies will increase, and demand will decline. Equilibrium will arrive, but vulnerability won’t be eliminated. That is an emerging supply chain constant as the economy shifts to the new normal.

The aftershocks of the pandemic and Russia’s war in Ukraine will be felt for a long time — and endured as inflation.

On Twitter: @llewellynking2

Llewellyn King is executive producer and host of White House Chronicle, on PBS. He’s based in Rhode Island and Washington, D.C.

‘There be dragons’

The Babcock House in Charlestown, built in the late 17th or early 18th Century.

—- Photo by JERRYE & ROY KLOTZ, M.D.

The town’s Quonochontaug section had an iron-mining operation financed by Thomas A. Edison in the 1880s. There were iron particles in the form of black sand on the beach there that could be separated out with magnets and melted to produce iron. But the venture collapsed after cheaper iron was later discovered.

Adapted from Robert Whitcomb’s “Digital Diary,’’ in GoLocal24.com

For such an amusingly tiny place, Rhode Island has intense localisms. Consider Kevin Gallup’s remarks. He’s a former police officer and now director of the Emergency Management Agency in Charlestown, in the exurban south of the state.

Mr. Gallup ominously warned, in comments about PVD Food Truck Events coming to Charlestown, that “things morph’’ and town residents “might not appreciate” having people from Providence come to town for events.

“If we’re going to have people showing up from Providence and hanging out that we don’t know…along with our children…some people aren’t going to appreciate that and I can tell you that for a fact. So you’re going to need that police detail. Sorry the world needs to be this way, but these things need to be thought out.”

There’s a long tradition of seeing cities as a source of menace, including in a “city state’’ such as Rhode Island. Do Charlestown people feel safer with visitors from smaller city New London, Conn., 34 miles from Charlestown, than with people from Providence, 48 miles away?

Remember those old maps that had the Latin phrase “hic sunt dracones” (“there be dragons”) for dangerous and/or unexplored regions? One wonders how familiar Charlestown people are with the capital of their state, and how many would say they’re all too familiar with it. People can be very provincial around here, and I’ll bet plenty of people from South County have never been to Providence.

Quonochontaug Pond.

Frank Carini: Working to reduce environmental impact of ocean racing sailboats

From ecoRI News (ecori.org)

While the United States flails about trying to reduce its enormous share of world-altering climate pollution, one part of the transportation/recreational sector is routinely ignored: boating.

Yachting and sailing are steadily gaining in popularity, so an urgency to act is essential if greenhouse-gas emissions are to be significantly reduced.

Yes, sailing burns little fossil fuel, but the resources consumed to build some of these vessels is swelling.

For instance, over the past decade, the carbon footprint of 60-foot International Monohull Open Class Association (IMOCA) racing boats has grown by nearly two-thirds, from 340 to 550 tons — the equivalent of driving an average car 1.4 million miles, according to the 11th Hour Racing Team.

“This is an overall trend we see in pretty much any industry, driven by performance we have accelerated too fast in the wrong direction, and are only just waking up to reality,” according to Damian Foxall, sustainability program manager for the 11th Hour Racing Team. “The need to reduce our emissions in the marine industry is urgent — 50% by 2030, and that’s just eight years away. We are far away from that right now.”

The 11th Hour Racing Team is sponsored by 11th Hour Racing, a Newport, R.I.-based nonprofit that works with the sailing community and maritime industries to “advance solutions and practices that protect and restore the health of our ocean.”

Late last year the team published a report about the importance of building a more sustainable ocean racing boat and better understanding the industry’s environmental impact. It showed performance doesn’t need to be sacrificed to build a more environmentally friendly boat.

“Business as usual is no longer an option. While the performance sailing sector and much of the leisure marine industry is geographically centered in the global North and a few other well-off regions, we live in a fragile bubble of prosperity,” according to the report. “This alternative reality does not reflect either the reality for most of the world’s citizens, or the availability of the earth’s resources.

“Inherently tied to the ongoing growth of global economies, we would need 1.7 Earths each year just to maintain the situation for the average global citizen. Scaled to the typical lifestyles associated with the marine industry this is more like 5+ Earths each year: a growing annual debt,” the report says.

The 128-page report includes a detailed study of material life cycles and alternative composites, such as flax to replace ubiquitous virgin carbon fiber. About 80 percent of greenhouse gas emissions in a boat build are associated with the use of composite materials, most notably carbon fiber, which is perfect for racing because it is light and stiff. Reducing the use of this material and others would significantly lessen climate emissions tied to the building of a new racing boat, according to the 11th Hour Racing Team.

In fact, the 11th Hour Racing Team and its partners are advocating for radical change across the marine industry to transform the way boats are built. They believe that only by “prioritizing sustainability along with performance, can the marine industry take urgent action to fight climate change.”

Foxall recently told ecoRI News that sustainable sourcing and using as much renewable energy as possible are the two biggest things racing teams can do right now to lower their carbon footprints.

The 11th Hour Racing Team, for instance, now leases an electric support vessel during races, which has lowered climate emissions from both a transportation and manufacturing perspective.

Foxall said rule changes would require sailing teams to incorporate more sustainable materials into their design and build. He noted, for example, reused carbon fiber is mostly avoided because the virgin material makes for better performance. But if rules required every team to use recycled fiber, no team would have an advantage.

“In our sport, rules define what the boats are … as much as one team or a couple of teams or even an event might want to improve the footprints, that cannot happen until the rules incentivize it,” Foxall said. “And the rules for the longest time have incentivized performance, whether it is carrying more sacks of coal or corn from Australia to Europe or transporting more people from Europe to North America or now racing faster and going faster through the water. It’s all about performance.”

He added the sport can no longer “just make decisions based purely on performance. We need to be taking into account the direct and indirect impacts” on the environment.

The December report recommends establishing minimum standards on sourcing, energy, waste, and resource circularity; defining a threshold for carbon emissions based on life cycle assessment (LCA) data; incentivizing the marine industry to use its inherent capacity for innovation to focus on sustainability; and setting an internal price for carbon emissions.

Amy Munro, sustainability officer for the 11th Hour Racing Team, noted the building of a racing boat is a complex process involving a number of stakeholders, materials, and components.

“You need to break it down in detail to fully understand what are the major impacts,” according to Munro. “This is why we have meticulously measured the impact of every step in the design and build process of our new boat and conducted a life cycle analysis that helps to uncover underlying issues.”

Last month, Charlie Enright, 11th Hour Racing Team skipper, spoke at the U.N.-supported One Ocean Summit in Brest, France, to highlight key findings of the organization’s “Sustainable Design and Build Report,” notably the importance of industry-wide collaboration to push sustainable innovation to align with the Paris Agreement.

“Within our sport, for too long we have chased performance over a responsibility for the environment and people,” the Bristol, R.I., native told an audience of experts, politicians, activists, and decision-makers. “We must work together to reduce the impact of boat builds, adopt the use of alternative materials like bio-resins and recycled carbon, lobby for a change to class and event rules to reward sustainable innovations, and support races and events that are managed with a positive impact on our planet and people.”

Foxall noted about 50 percent of sailors are onboard when it comes to making their sport more sustainable. He said it is their responsibility to bring the others up to speed about the impacts of the climate crisis.

In an email to ecoRI News, Enright noted the sport’s awareness of climate and environmental issues is “definitely increasing.” He said big events such as The Ocean Race and the Transat Jacques Vabre have “strong sustainability policies” in place, including plastic-free race villages, onboard waste calculation initiatives, and efforts to educate teams and fans about these matters. “This is relatively new in our sport.”

The Ocean Race also runs an ocean science program in partnership with 11th Hour Racing, collecting data on water temperature, salinity, and other potential climate change impacts. The Transat Jacques Vabre uses the 11th Hour Racing Team’s Sustainability Toolbox, which, among other things, commits to efforts to limit waste, use renewable energy and reduce emissions wherever possible, as a framework for its own sustainability program.

“Of course there are those who need a bit more convincing on the importance of it,” Foxall said. “But, quite frankly … kids coming home from school today know what the issue is.”

In 2019, greenhouse-gas emissions from ships and boats in the United States alone totaled 40.4 million metric tons of carbon dioxide equivalent. Globally, bulk carriers are the main source of shipping/boating climate emissions. Some 90 percent of world trade is carried across the world’s oceans by some 90,000 marine vessels. Carbon dioxide emissions from these vessels are largely unregulated.

Last year, the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) did adopt exhaust emission standards for marine diesel engines installed in a variety of marine vessels, ranging in size and application from small recreational boats to large ocean-going ships.

While the shipping industry is responsible for a significant proportion of global climate emissions — if global shipping were a country, it would be the sixth-largest producer of greenhouse gases behind China, the U.S., Russia, India and Japan — the climate impacts of the recreational powerboat industry, most notably yachts, are considerable.

The propulsion systems on many yachts are arguably the least-efficient modes of transportation ever devised. The typical 40- to 50-foot yacht guzzles fuel.

U.S. recreational boaters spend about 500 million hours annually cruising fresh and salt waters. In 2010, more stringent EPA emissions standards for marine engines, both in-board and outboard, went into effect. But, unlike cars, private boats are not inspected. They can be checked by the Coast Guard or law enforcement, but there is no annual emissions check.

Many recreational boats and some jet-propelled watercraft have two-stroke engines. Conventional two-stroke engines produce about 14 times as much climate pollution as four-stroke engines.

Last year new U.S. powerboat sales surpassed 300,000 units for the second consecutive year, closing 2021 about 6 percent below record highs in 2020 and some 7 percent above the five-year sales average, according to the National Marine Manufacturers Association. In 2020, annual U.S. sales of boats, marine products and services totaled $49.3 billion, up 14 percent from 2019.

The oceans play an essential role in keeping atmospheric carbon dioxide in balance by absorbing about 30 percent of the CO2 that is released, from all sources. This blue carbon sink, however, has been working overtime since the Industrial Revolution began belching fossil fuels into the atmosphere.

The ocean, though, can only swallow so much of this colorless gas. When carbon dioxide is absorbed by seawater, chemical reactions occur that increase the acidity of the water through a process known as ocean acidification.

Acidifying marine waters are bad news for marine life with calcium carbonate in their shells or skeletons, such as oysters, corals, crabs, scallops, and mussels. Studies have found that more acidic salt waters make it more difficult for them to develop their hardened protection.

As of early last month, the recorded amount of carbon dioxide in the atmosphere was a tick away from 418 parts per million (ppm) — well beyond the 350 ppm that climate scientists have deemed safe for humans, never mind most of the planet’s other living inhabitants.

“While the situation is extremely urgent and ‘business-as-usual’ is clearly no longer an option, it is still technically possible to close your eyes and look away,” Enright wrote. “This is why we have to act now and we have to create our own pressure. What we need is a radical change and one of the most important parts here is that the marine industry works together to achieve it.”

Frank Carini is co-founder and senior reporter of ecoRI News.

Azzam, at 592.5 feet, was the longest superyacht, as of 2020.

— Photo by ChrisKarsten

Plastic Providence

This work by Rhode Island artist Jim Bush can be seen at the Providence Art Club March 6-25.

Here’s his description of his background:

“Jim Bush grew up in Cambridge, Mass., and graduated from Kenyon College with a double major in Studio Art and Political Science. He is an award-winning artist, member of the Providence Art Club and a former member of the Sakonnet Artists Cooperative, in Tiverton, R.I. His editorial cartoons appeared in The Providence Journal from 1994-2012. Nationally his cartoons have appeared in the Washington Post National Weekly Edition, The Dallas Morning News and he has drawn for the Tribune Media Services College Press Syndicate.

“In 2007, Jim purchased a building in the historic district of downtown Warren, R.I. and spent a year converting it into an art studio and gallery. Jim focuses now on his fine art painting, primarily acrylic and watercolor. He enjoys painting animals, seascapes, landscapes, farm scenes, architecture -- life around him. His style continues to reflect his cartooning foundation, often displaying his subjects in a light-hearted and off-beat way.’’

Llewellyn King: Trying to spread the innovation culture to old businesses

100, 300, and 500 Technology Square, in Cambridge, Mass., as seen from Main Street. The neighborhood has been the site of many technological breakthroughs for decades.

WEST WARWICK, R.I.

Microsoft is buying, subject to regulatory approval, Activision Blizzard for $69 billion. The Internet of Things is white-hot and likely to remain so.

If you want to whistle at that humongous sum for a company that makes games, you may have to add many octaves to the known musical scale.

Yes, high-tech is chasing trivia. The imperative at work here is if you don’t get your latest game into the market, someone else will. The threshold of entry is low and the rewards are astronomical.

If you are talking innovation and creativity, you are talking the Internet. That means that whole areas of society aren’t progressing as fast as they might and should. There is asymmetry.

The Internet firmament is driven not by market demand, but by a business dynamic that exists in the world of internet entrepreneurism: Innovate and create because the internet can create great wealth — and take it away, too.

Most non-Internet companies — and I talk to a fair number of CEOs — say that they are innovative and that they are innovation-driven but, in fact, they aren’t. Most companies don’t need to innovate the way the internet giants do. The metaverse is demonstrably an unstable place.

Most companies are looking for stability, for a plateau where they can manage what has been created while adding to it cautiously, often by acquisition. They confuse innovation with evolutionary improvement. The last thing they want is the kind of destructive innovation that characterizes Silicon Valley.

The febrile need to innovate in the Internet world is unique to that world. This because internet companies are all on a treacherous slope; failure can come as fast as success. Remember MySpace, Nokia, Palm, and Wang?

The Internet is global, and it is intrinsically favorable to monopoly. In the internet world, first past the post takes the prize money — all of it.

When you have market caps that value a company at $1 trillion, and all of that is dependent on the next innovation not overtaking you, you are going to throw money and talent at innovation because the alternative is known. Whenever possible, you are going to buy up your competition, hence the Microsoft purchase.

With all of the money, all of the glamor, all of the talent, there also is fear that some kid in a garage somewhere will invent the next big thing.

I submit that for the non-Internet world the business dynamic is very different. Most CEOs of public companies, snug in their C-suites and buttressed by huge salaries, are seeking a quiet place; a plateau where profits grow but there is some business serenity. For example, Boeing doesn’t want new airframes, it wants upgraded models.

They won’t admit to it, but many businesses long to be rent takers (known collectively as rentiers). They want a steady income with small risk.

Unfortunately, the business culture, including that spawned in business schools, aims to channel ambition into the rent-taking model. We have a business culture where ambition is channeled toward climbing to the top of the established order, not creating a new order.

There are many excellent minds managing established companies, often established many decades earlier, but there are few who yearn to create something wholly new.

The great names of management are many, but the great names of true innovation are few. Almost always, they have to break away from the established to create the new, to alter the world.

My friend Morgan O’Brien, the co-creator of Nextel, and now the executive chairman of the pioneering wireless company Anterix, is that kind of innovator who saw new horizons and went for them.

Today’s standout inventor is Elon Musk. He began as an Internet whiz with PayPal and has blazed the innovation trail like no other since Thomas Edison, more than a century earlier. He has changed the world underground with new concepts of subways, changed surface transportation by going electric, and changed space with his rockets.

Thirty years ago, I wrote that the weakness of U.S. companies is that they are happy to make silent movies when the talkies have been invented. Today, the established auto manufacturers are hell-bent to make electric pickup trucks now that new entrepreneurs are in the truck market with electric trucks. They never wanted to abandon the internal-combustion engine, just improve it a little at a time.

If the dynamic of the Internet and its constant innovation is missing in most American businesses, it needs to be grafted onto the business body politic. Must the Internet be behind every innovation of consequence? Ride-sharing and additive manufacturing (3D printing) are all computer-driven — software at work.

The challenge for the business culture is to harness ambition – it is never in short supply — and point it not toward the greasy pole of promotion, but toward the firmament of innovation.

On Twitter: @llewellynking2

Llewellyn King is executive producer and host of White House Chronicle, on PBS. He’s based in Rhode Island and Washington, D.C.

White House Chronicle

Llewellyn King: Utilities urgently need to add transmission

In Seekonk, Mass., during the height of the Jan. 29 blizzard. Many people in southeastern Massachusetts lost power in the storm, in which winds gusted to hurricane force.

Logo of Independent System Operator, which oversees the region’s electric grid.

WEST WARWICK, R.I.

It has become second nature. You hear that bad weather is coming and rush to the store to stock up on bottled water and canned and other non-perishable foods. You check your flashlight batteries.

For a few days, we are all survivalists. Why? Because we are resigned to the idea that bad weather equates with a loss of electrical power.

What happens is the fortunate have emergency generators hooked up to their freestanding houses. The rest of us just hope for the best, but with real fear of days without heat.

It happened most severely in Texas in February 2021; during Winter Storm Uri, which lasted five days, 250 people died. Recently, during the Blizzard of 2022, on Jan. 28-29, 100,000 people in Massachusetts endured bitter cold nights when the electricity failed. There were more power failures in the most recent ice storm.

There are 3,000 electric utilities in the United States. Sixty large ones, like Consolidated Edison, NextEra Energy, Pacific Gas and Electric, and the Tennessee Valley Authority, supply 70 percent of the nation’s electricity. Nonetheless, the rest are critical in their communities.

All utilities, large and small, have much in common: They are all under pressure to replace coal and natural gas generation with renewables, which means solar and wind. No new, big hydro is planned, and nuclear is losing market share as plants go out of service because they are too expensive to operate.

The word the utilities like to use is resilience. It means that they will do their best to keep the lights on and to restore power as fast as possible if they fail due to bad weather. When those events threaten, the utilities spring into action, dispatching crews to each other’s trouble spots as though they were ordering up the cavalry. The utilities have become very proactive, but if storms are severe, it often isn’t enough.

Now, besides more frequent severe weather events, utilities face the possibility of destabilization on another front, due to switching to renewables before new storage and battery technology is available or deployed.

The first step to avoid new instability -- and it is a critical one -- is to add transmission. This would move electricity from where it is generated in wind corridors and sun-drenched states to where the demand is, often in a different time zone.

Duane Highley, president and CEO of Tri-State Generation and Transmission Association, which serves four states in the West from its base in Westminster, Colo., says new west-east and east-west transmission is critical to take the power from the resource-rich Intermountain states to the population centers in the East and to California.

“Most existing transmission lines run north to south. They aren’t getting the renewables to the load centers,” Highley says.

Echoing this theme, Alice Moy-Gonzalez, senior vice president of strategic development at Anterix, a communications company providing broadband private networks that make the grid more secure and efficient, sees pressure on the grid from renewables and from new customer demands (such as electrical vehicles) as electrification spreads throughout society.

“The use of advanced secure communications to monitor all of these resources and coordinate their operation will be key to maintaining reliability and optimization as we modernize the grid,” Moy-Gonzalez says.

Better communications are one step in the way forward, but new lines are at the heart of the solution.

The Biden administration, as part of its infrastructure plan, has singled out the grid for special attention under the rubric “Build a Better Grid.” It has also earmarked $20 billion of already appropriated funds to get the ball rolling.

Industry lobbyists in Washington say they have the outlines of the Department of Energy plan, but details are slow to emerge. Considered particularly critical is the administration’s commitment to ease and coordinate siting obstacles with the states and affected communities.

Utilities are challenged to increase the resilience of the grid they have and to expand it before it becomes more unstable.

Clint Vince, who heads the U.S. energy practice at Dentons, the world’s largest law firm, says, “We aren’t going to reach the growth in renewables needed to address climate without exponential growth in major interstate transmission. And sadly, we won’t succeed with that goal on our current trajectory. We will need significant federal intervention because collaboration among the states simply hasn’t been working within the timeframe needed.”

Better keep the flashlights handy.

Llewellyn King is executive producer and host of White House Chronicle, on PBS. His email is llewellynking1@gmail.com, and he’s based in Rhode Island and Washington., D.C.

Linda Gasparello

Co-host and Producer

"White House Chronicle" on PBS

Mobile: (202) 441-2703

Website: whchronicle.com

Warren Getler: This most uncertain winter

Luce Hall (1884) at the U.S. Naval War College, in Newport, R.I. The institution is a center of the U.S. military’s war-gaming work.

—U.S. Navy photo by Jaima Fogg

Ukrainian troops in the threatened country’s Donbas region. Russia has been massively increasing its troop strength nearby in what some observers fear is a precursor to an all-out invasion.

America faces its most challenging year-end since its formal entry into the Second World War, in December 1941.

While we have been internally grappling with COVID for nearly two years, dark clouds have gathered on the geopolitical map.

Russia is mobilizing some 175,000 troops on its border with Ukraine; China is flying repeated bomber test-runs near Taiwan; Iran is using its proxies to hit its Arab neighbors as well as Israel and U.S. bases in Iraq and Syria with drones and missiles. Russia and China are exhibiting their closest military collaboration – in joint-training exercises and bilateral arms sales – in decades. And both have signed military and economic pacts with Iran in recent years.

Will there be war, indeed, continental war, on several fronts?

The risk may be greater than at any time since World War II.

Authoritarian rulers-for-life in Moscow and in Beijing are testing the waters. Specifically, they are testing the mettle of U.S. President Joe Biden and his first-year administration. They’re gauging a Biden preoccupied with internal debates around vaccination policies, inflation, crime, supply-chain bottlenecks and other largely domestic, massively time-consuming matters.

And they perceive vulnerability in the Oval Office – with Biden, who just turned 79, coming off a grueling multi-year presidential campaign against incumbent Donald Trump and then seeing his approval ratings drop for months. What’s more, they sense a country deeply divided -- an American superpower at growing risk of civil unrest.

Are these Russian and Chinese military maneuvers mere provocations, mere signals of what could happen if the West challenges their geopolitical ambitions?

Or are these up-tempo deployments by Russia’s Putin and China’s Xi meant merely for domestic Russian and Chinese consumption? Possibly not.

This time, the activity around such large-scale mobilizations appears alarmingly furtive, and therefore open to wide interpretation, particularly regarding Moscow’s intentions toward Ukraine. These maneuvers (including rumors of a planned assault on eastern Ukraine in late January or early February) may invite retaliation and potential “miscalculations” by both sides. Putin and Xi may not appreciate the seriousness of possible "kinetic" responses by NATO allies and our friends in Asia. Israel, meanwhile, uncertain of backing from Washington, is leaning toward taking things into its own hands to stop -- with direct military action from the air -- a nuclear-armed Iran from emerging.

America, as the world’s leading democracy, is slow to anger, which is a good thing. Yet we are also at times too slow in confronting harsh realities beyond our borders. As a nation, we must focus on the large-scale threat scenarios developing in Europe, East Asia and the Middle East…with level-headed coolness and a serious, sustained focus.