History of India in New England; Llewellyn King on what holds back that huge nation

Sri Lakshmi {Hindu} Temple, in Ashland, Mass.

— Photo by Tshiv

From “The Indian Presence in New England: People and Ideas” . Hit this link to read the whole article.

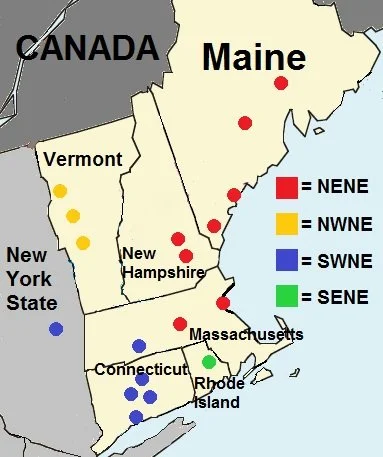

“There were some exceptions to this general atmosphere of non-acceptance {of Indians in America}. In general, the intellectuals of the Northeast were not active participants in such overt racialized discourse. Jane Jensen states that New England intellectuals developed a deep interest in Indian religions in the early 19th century, at about the time the New England-India trade developed. She describes how Boston society became interested in Indian literature and in Indian religions, especially Hinduism, Buddhism and the Brahmo Samaj movement. Intellectuals at universities such as Harvard began to cultivate an active scholarship and also initiated a nascent Indian art collection at the Boston Museum of Fine Arts. The theosophical writing of Ralph Waldo Emerson and Henry David Thoreau, as well as Walt Whitman’s poems (such as “Passage to India” and “Leaves of Grass”), are reflective of this trend. These earlier writings of the Transcendentalists, on the “life of the spirit” (developed on the basis of an earlier encounters with Hinduism), prepared the ground for Vivekananda and his message.’’

Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi

By Llewellyn King

WEST WARWICK, R.I.

By the diplomatic hoopla in Washington that greeted Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi last week, it would seem that intrepid U.S. explorers had just discovered India and were celebrating him in the way Britain treated tribal leaders in the 19th Century: Show them the big time. Then co-opt them to vow allegiance.

In this century, the U.S. equivalent of the big time is a state visit and endless professions of friendship. Experience says Modi won’t bite.

Historically, India has been reluctant to accept the embrace of the West. Although it is democratic, capitalist and has the largest diaspora, India’s affections have been hard to capture.

Since independence from Britain in 1947, India has sought global status by standing aloof and leaning toward countries and regimes that are anathema to the West. Its first prime minister, Jawaharlal Nehru, fostered the concept of a third force in the world: a constellation of unaligned nations with India at the center.

It showed a perverse affection for the Soviet Union — which was hardly nonaligned — and didn’t reflect the values of India: free movement of people, free press, capitalism and democracy.

Years ago, a retired executive editor of the Times of India, whom I knew socially, told me, “There are maybe a million Indians living in the United States and only a handful who live in the Soviet Union, but our leaders have always leaned toward them. It is a puzzle.”

There are now 4.2 million Indians living in the United States.

At the same time, Indians migrated across the world and made inroads into professions from Canada to New Zealand. In Britain, they are prominent in politics and the prime minister, Rishi Sunak, is of Indian descent.

In the United States, executives of Indian descent run some of the largest tech companies, including IBM, Google and Microsoft.

Indians are a huge force in English literature. Every year Indian writers feature on the prize lists for best new English novels. Whereas the computers most of us use may have been made in China, much of the software was written in India.

Indian words abound in English: Pajamas, ketchup, bungalow, jungle, avatar, verandah, juggernaut and cot are just a few.

The effect of Indian culture on the world is evident from curry and rice to polo to yoga.

Yet, India remains a distant shore, elusive and obvious at the same time. A country of enormous talent that lags economically. It now has the fifth-largest economy in the world. With 1.4 billion people, many of whom of obvious ability, the question must be, why does it still have crushing poverty?

Andres Carvallo, professor of innovation at Texas State University, told the “Digital 360” webinar, for which I am a regular panelist, he thought it was partly because India lagged in essential electricity production, pointing out that China has four times the electricity output of India.

But is this symptom or cause? I have been puzzling over why India doesn’t do better for decades. It seems to me that the causes are multiple, but some can be laid at Britain’s feet — not because the British were occupiers in India but because of some of the good things they left there that have perversely remained time-warped.

One of India’s ambassadors to Washington told me with pride that every occupier had enriched India and left something of value behind, from Alexander the Great to the Moguls and, of course, Britain and the Raj.

But the Brits also left behind a sluggish bureaucracy to the point of sclerosis and a legal system that is independent but takes an eternity to reach a decision. Additionally, some of the ideas prevalent in British Labor Party thinking — and long since abandoned — took hold in India and have been extremely detrimental. These included protectionism, a state’s role in the economy, and a fear of competition from abroad.

I believe that protectionism is the greatest evil. It discouraged competition, innovation and creativity. It inadvertently allowed a few families to concentrate too much wealth and economic power and to work to protect that.

India is more open now, but it needs to be vigilant against the evils that go with protectionism, which is still part of its DNA.

At one time, you could buy a brand-new Indian made-car — Fiat or Morris design — which was 30 years out of date. No need to innovate; just make the same car year after year.

If it liberalizes its economy, India may one day outpace China. Meantime, do luxuriate in those Indian words that have so spiced up English.

Llewellyn King is executive producer and host of White House Chronicle, on PBS. He’s based in Rhode Island and Washington, D.C.

On Twitter: @llewellynking2

Watch or Listen to White House Chronicle

Streaming: All episodes are free to watch on Vimeo [link]

On television: Visit our website [link] to find your location carrying station.

SiriusXM radio: Listen to White House Chronicle on P.O.T.U.S., Channel 124: Saturday at 8 a.m. and 6 p.m. ET; and Sunday at 4 p.m. and 11 p.m. ET.

#India

#White House Chronicle

Being adaptable

“If you've worn shorts and a parka at the same time, you live in New England.’’

“If you have switched from 'heat' to 'A/C' in the same day and back again, you live in New England .”

—Jeff Foxworthy (born 1958), American actor, author, comedian, producer and writer. He grew up in Georgia.

Heat pumps are particularly effective in places with wildly variable temperatures such as New England.

Beech tree disease imperils forest ecosystem

American beech tree

— Photo by Jean-Pol GRANDMONT

From ecoRI News (ecori.org) article by Mike Freeman

Beech leaf disease, which has devastated northern hardwood forests since its discovery in Ohio in 2012, has spread throughout Rhode Island’s beech trees.

“It would change the whole forest ecosystem if they go,” said Heather Faubert, director of the University of Rhode Island’s Plant Protection Clinic. “We know what’s infected them but don’t know yet how it spreads, only that it spreads very quickly. It was first identified in Ashaway in 2020 and is now statewide.”

The disease is infecting beech trees in all New England states except Vermont, and was first detected in Connecticut in 2019.

Faubert’s general description tracks the terrible template that has wiped out or is en route to wiping out several native North American tree species. Details differ, but the plot never changes: People notice dying trees, a cause is identified, swaths of forest succumb as more becomes known, then to various effects preventative, palliative, or restorative measures are taken, often in combination. American chestnut exists on life support, American elm is greatly diminished, and currently eastern hemlock, the entire ash genus, and now American beech are all in dire peril.

As Faubert noted, what exactly causes beech leaf disease (BLD) and how it spreads are currently unknown, though the critical vector is Litylenchus crenatae mccannii, a nearly microscopic nematode, or worm, that feeds on beech leaves.

To read the whole article, please hit this link.

Your N.E. house-tour assistant

William (“Willit’’ ) Mason, M.D., has written has a delightful – and very handy -- book rich with photos and colorful anecdotes, called Guidebook to Historic Houses and Gardens in New England: 71 Sites from the Hudson Valley East (iUniverse, 240 pages. Paperback. $22.95). Oddly, given the cultural and historical richness of New England and the Hudson Valley, no one else has done a book quite like this before.

The blurb on the back of the book neatly summarizes his story.

“When Willit Mason retired in the summer of 2015, he and his wife decided to celebrate with a grand tour of the Berkshires and the Hudson Valley of New York.

While they intended to enjoy the area’s natural beauty, they also wanted to visit the numerous historic estates and gardens that lie along the Hudson River and the hills of the Berkshires.

But Mason could not find a guidebook highlighting the region’s houses and gardens, including their geographic context, strengths, and weaknesses. He had no way of knowing if one location offered a terrific horticultural experience with less historical value or vice versa.

Mason wrote this comprehensive guide of 71 historic New England houses and gardens to provide an overview of each site. Organized by region, it makes it easy to see as many historic houses and gardens in a limited time.

Filled with family histories, information on the architectural development of properties and overviews of gardens and their surroundings, this is a must-have guide for any New England traveler.’’

Dr. Mason noted of his tours: “Each visit has captured me in different ways, whether it be the scenic views, architecture of the houses, gardens and landscape architecture or collections of art. As we have learned from Downton Abbey, every house has its own personal story. And most of the original owners of the houses I visited in preparing the book have made significant contributions to American history.’’

To order a book, please go to www.willitmason.com

#Great New England houses

James T. Brett: Fixing federal tax code for technology is crucial for protecting New England’s prosperity

The Media Lab at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, in Cambridge, houses researchers developing novel uses of computer technology. Greater Boston has long been one of the world’s greatest technology centers, primarily because spinoffs from its universities.

— Photo by Madcoverboy

BOSTON

Here in New England, we are proud of our region’s reputation as a global innovation hub. Our region hosts some of the world’s most innovative companies, in industries ranging from defense to life sciences to clean energy to technology. Each day, these businesses are making investments in ground-breaking research and development aimed at saving lives, combating climate change, safeguarding our national security and more.

For many years, the U.S. tax code has encouraged such investments by allowing businesses to fully deduct qualified research and development (R&D) expenses each year. However, under a provision of the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act of 2017, which was signed into law by then-President Trump, businesses must amortize or deduct these expenses over a period of five years. This provision went into effect for the 2022 tax year.

This will ultimately make R&D more costly to conduct in New England and across the U.S. The New England Council believes firmly that the new R&D amortization requirement will halt and harm our region’s continued growth and leadership on the global stage.

As a result of this change, the U.S. is now only one of two developed countries requiring the amortization of R&D expenses. Comparatively, our nation’s competitors, such as China, currently provide a “super deduction” for R&D expenses that drastically increases the allowed amount deducted for companies that previously did not qualify.

This change could result in companies relocating R&D facilities and funding out of the country, because it will be more costly to do research in the U.S. This will not only damage our competitiveness, but it could also have significant national security ramifications, as well as job losses.

In fact, a recent study conducted by EY for the R&D Coalition found: “Failing to reverse this change will cost well-paying jobs and reduce future innovation-directed R&D. Requiring the amortization of research expenses will reduce R&D spending and lead to a loss of more than 20,000 R&D jobs in the first five years with the number of lost jobs rising to nearly 60,000 over the following five years. Moreover, when accounting for the spillover effect from R&D spending, nearly three times as many jobs will be affected. This same study also found that for every $1 billion in R&D spending, 17,000 jobs are supported in the U.S.”

Fortunately, two members of Congress from New England are among those leading the bipartisan charge to reverse this harmful change in the tax code.

In the U.S. Senate, Sen. Maggie Hassan ( D.-N.H.) has partnered with Sen. Todd Young (R.-Ind.) to introduce the American Innovation and Jobs Act. In addition to allowing companies to fully deduct R&D expenses each year, Senator Hassan’s bill would also raise the cap over time for the refundable R&D tax credit for small businesses and startups, and expand eligibility for the refundable R&D tax credit so that more startups and new businesses can use it.

In the U.S. House, Congressman John Larson (D.-Conn.) has teamed up with Rep. Ron Estes (R.-Kan.) to introduce similar legislation, known as the American Innovation and R&D Competitiveness Act. Similar to the Senate bill, Representative Larson’s proposal would allow companies to continue to fully deduct R&D expenses each year.

The New England Council is proud to support both of these bills, and we urge others in the business community to also encourage Congress to pass this legislation. We have written to members of the New England congressional delegation, calling on them to support these bills, and are hopeful that Congress will take action to pass them in the near future.

Doing so will help ensure that the U.S. remains globally competitive, and it will drive continued innovation and job creation right here in New England, ensuring that the region remains a global innovation hub.

James T. Brett is president and CEO of The New England Council (newenglandcouncil.com)

Colleges’ huge economic impact on New England

Flag of The New England Conference

Hit this link for a look at the economic impact of higher education in New England.

Ellen Reed House, home of the English Department faculty at Plymouth (N.H.) State University, in the foothills of the White Mountains

— Photo by Tysei91

The Puritans didn’t like it but we moved on

On the Easter Bunny Express of the Railroad Museum of New England, in Thomaston, Conn.

From the New England Historical Society:

“Easter Sunday traditions in New England have long included dying eggs, wearing new clothes, baking hot cross buns and attending sunrise services. They are based on pagan superstitions, which of course is why the Puritans didn’t celebrate the holiday. (The Puritans didn’t like Christmas, either.) For the early Puritans, celebrating the Lord’s Day 52 times a year was quite enough.

“Others brought traditions from Europe. Germans believed, for example, that rabbits laid beautifully colored eggs on Easter.

“Franco-Americans rose before the sun came up to fetch water, which they called Peau de Paques (Easter skin) from a stream. They believed it had miraculous qualities, staying pure indefinitely. They washed with it, drank it and saved it.’’

‘Four seasons at once’

“The best way to describe Spring in New England is an awakening. It feels like everyone is coming out of hibernation after a quiet and cold winter. First the daffodils bloom then we have the cherry trees and tulips. Sometimes we experience all four seasons at once with a rainy morning, warm afternoon, and an overnight frost but that’s what makes it so special. You never know what to expect, only that summer is waiting for you on the other side.’’

Rhode Island photographer Caitlin James in Shorelines Illustrated

Who makes this stuff?

The June 1, 2011 tornado that killed three people in and around Springfield, Mass.

— Photo by Runningonbrains

“I reverently believe that the Maker who made us all makes everything in New England but the weather. I don’t know who makes that, but I think it must be raw apprentices in the weather clerk’s factory who experiment and learn how, in New England, for board and clothes, and then are promoted to make weather for countries that require a good article, and will take their custom elsewhere if they don’t get it….’’

–Mark Twain (1835-1910)

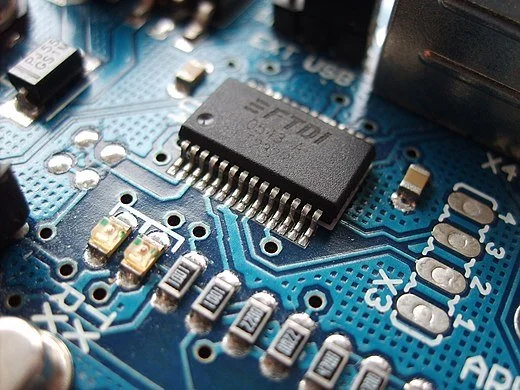

A pitch to create a microelectronics hub in New England

Edited from a New England Council (newenglandcouncil.com) report

“A coalition of New England businesses and institutions have applied to the U.S. Department of Defense (DOD) for funding under the recently passed CHIPS and Science Act to establish as Microelectronics Commons hub in the Northeast. The coalition is led by the Massachusetts Technology Collaborative and includes a number of other NEC member businesses and educational institutions.

“In November 2022, the Department of Defense launched its Microelectronics Commons program following the passage of the CHIPS and Science Act in August with the goal of linking U.S. R&D with manufacturing capacity. DOD plans to establish nine regional microelectronics-technology hubs across the nation and has $1.63 billion to invest.

“A main goal of this plan is to ‘bring ideas from the lab to the bench.’ If the coalition’s application for funding is accepted, the new hub in New England would link dozens of research, manufacturing and academic partners to grow a regional defense technology ecosystem, opening doors to major federal grants.

“Our region has an incredible depth of research, talent, and facilities across industry and academia needed to help the DoD deliver on the Microelectronics Commons vision,” said Doug Robbins, vice president, Engineering and Prototyping, at MITRE.

'Lights a window in Amherst'

“It’s New England time,

the sun

comes like an old puritan

and it rises over the ocean

and gives leave to the flight of the birds,

it lights a window in Amherst

where the eyes of a woman contemplate the world….’’

— From “The Balada of New England,’’ by Fernando Valverde (born 1980), translated from the Spanish by Carolyn Forche. The “woman’’ referred to is Emily Dickinson (1830-1886), the famed poet.

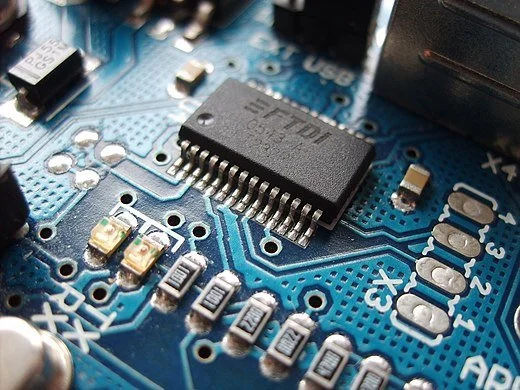

'Ignorant hayseed" and 'pompous ignoramus'

Northeastern (NENE), Northwestern (NWNE), Southwestern (SWNE), and Southeastern (SENE) New England English represented here, as mapped by the Atlas of North American English.

"Basically, there are two New Englands, northern and southern, with plenty of shared schizophrenia between them....The Connecticut Yankee and the Maine Yankee may both trade on rurality for their wit, but one is garrulous and the other taciturn. When the Bostonian tells a story the Vermonter becomes an ignorant hayseed; when the Vermonter tells a story the Bostonian is a pompous ignoramus. Usually in such a match there's no contest; the Vermonter will inevitably prevail.''

-- From Jim Brunelle, in The Best of New England Humor

George McCully: We need to battle AI robotization

From The New England Journal of Higher Education, a service of The New England Board of Higher Education (nebhe.org)

Every reader of this journal is being affected by the highly exceptional historical phenomenon we are all experiencing: an age of total transformation, of paradigm-shifts in virtually every field of human endeavor. Our own field—postsecondary education and training—is just one among all the others. Younger colleagues, though they may not like it, are experiencing this as a given and generally constructive condition, building their future theaters of operations. Senior colleagues raised and entering the profession in the 20th Century paradigm of “higher education,” experience current transformations as disruptive—disintegrative and destructive of their originally sought-for and later accustomed professional world. Students seeking credentials for future jobs are confused and problematically challenged.

It helps to understand all this turmoil as an inexorable historical process. This article will describe that process, and then address how we individually, and organizations like NEBHE, might best deal with it.

We happen to be living in a very rare kind of period in Western history, in which everything is being radically transformed at once. Paradigm-shifts in particular fields happen frequently, but when all fields are in paradigm-shifts simultaneously, it is an Age of Paradigm Shifts. This has happened only three times in Western history, about a thousand years apart—first with the rise of Classical Civilization in ancient Greece; second with the fall of Rome and the rise of medieval Christianity; and third in the “early modern” period—when the Renaissance of Classicism, the Reformation of Christianity, the Scientific Revolution, the Age of Discovery, the rise of nation states, secularization and the Enlightenment, cumulatively replaced medieval civilization and gave birth to “modern” history in the 19th and 20th centuries.

Modernity, however, is now unraveling, in a transformation with significant unique features.

First and most noticeable is its speed, occurring in a matter of decades (since circa 1990) rather than centuries. The acceleration of change in history, driven by technology’s increasing pace and power, has been going on for centuries—perhaps first noticed by Machiavelli in the Renaissance. Today, the driving transformational force is the rapidly accelerating innovations in digital and internet technology, in particular, increasingly autonomous Artificial Intelligence (AI).

Second, for the first time our technology is increasingly acknowledged to be running ahead of human control; it is becoming autonomous and self-propelled, and we are already struggling to catch up with it.

Third, whereas the first three transformations were intended by human agents, for the first time now, driven by technological advances, we have no clue as to where the technology is headed—what will be the dénouement or if that is even possible.

And fourth, under these conditions of constant change both internally and all around us, strategic planning in any traditional sense is impossible because there are no solid handles we can grasp and hold onto as collaborators or guides into the future. We are adrift in an unprecedently tumultuous sea of change.

For people in post-secondary education and training, this critical situation is especially agonizing because we are in society at various thresholds of adulthood, where personal and professional futures are crucially chosen and determined. We have extraordinarily heavy responsibility for the futures of individuals, of society, of humanity and of our planet—precisely when we have inadequate competence, coordination and self-confidence. We are where humans will address the innovations and disruptions critical to the future, where strategic knowledge and intelligence will be most needed, and where historical understanding will therefore be crucial.

Let us first acknowledge that each, and all, of our jobs sooner or later, can and probably will be robotized by AI. Its technical capacity already exists, noted by many journalists and scholars, for thinking and writing (publicly available GPT-3, and next year GPT-4), visual and musical arts, interactive conversations, cerebral games (chess, Go, et al.) and other problem-solving activities, at quality levels equal to and frequently excelling human-generated work. Significant technological advances are happening almost weekly, and AI nowadays develops these autonomously, written in code it developed for its own machine-learning use. Its aims are not excellence, truth or other value-intensive products, but common-denominator performances adequate to compete commercially with works created by humans and indistinguishable (by humans—though software is being developed intended do this) from them, produced at blinding speed. Suddenly there could appear countless new “Bach” fugues, novels in Hemingway’s style, etchings by Rembrandt, news articles and editorials or academic work—all mass-produced by machines.

Administrative functions—numerary, literary, interactive, decision-making, etc.—will be widely available to ordinary individuals and institutions. What will remain for which humans are needed to do, at prices that yield living wages, is a real question already being considered hypothetically.

Speed bumps helping to shield us from faster robotization are (temporarily at least) the availability of sufficient capitalization, and the time required for dissemination. Here, the fact that we work much more slowly than AI is a temporary but ultimately self-defeating blessing. The driving incentive for takeover is the robots’ greater cost-effectiveness. In the long run, robots work more cheaply and much faster than humans, outweighing losses of quality in performance.

For individuals, our best defense against robotic takeover is for each of us to identify and enhance whatever aspects of our jobs that humans can still do best, which means that we should all start redefining our work in humanistic and value-intensive directions, so that when robotization comes knocking, decision-makers will go for the low-hanging fruit, allowing the easiest transitions first, leaving some margins of continued freedom for humans to continue doing their jobs.

A clear possibility, and I believe necessity, for postsecondary education and training lies in that distinction, extending from individuals’ lives and work to institutions and organizations like NEBHE and their instruments such as this journal. The rise of machine learning (AI) is a wedge, compelling us to cease referring to all post-secondary teaching and learning as “higher education.” There is nothing “higher” about robotic training and commercial credentialing for short-term “gig economy” job markets. Let us therefore first define our terms more carefully and precisely.

“Education,” as in “liberal education,” traditionally means “self-development”; “training” customarily means “knowledge and skills development.” The two are clearly distinct, but not separate except in extreme cases; when mixed, the covering designation depends on which is primary and intentional in each particular case.

In other words, our education helps define who we are; our training helps define what we are—doctor, lawyer, software engineer, farmer, truckdriver, manufacturer, etc. Who we are is an essential and inescapable part of all of our lives that’s always with us; what we are is optional—what we chose to do and be at given times of our lives.

Education is intrinsically humanistic and value-intensive, therefore most appropriately (but not necessarily) taught and learned between humans; training can be well-taught by AI, imparting knowledge and skills from robots to humans. Ideally, to repeat for emphasis, both education and training usually involve each other in varying proportions—when education includes knowledge and skills development, and training is accompanied by values. But these days especially, we should be careful not to confuse them.

For individuals, certainly education and possibly training are continuing lifelong pursuits. AI will take over training most easily and first, especially as rapid changes and transformations overtake every field, already producing a so-called “gig” economy in which work in any given capacity increasingly becomes temporary, more specialized and variegated, affecting the lives and plans of young employees today. Rapid turnover requires rapid increases in training, certifying, credentialing programs and institutions. Increasing demand for it has evoked many new forms of institutionalization—e.g., online and for-profit in addition to traditional postsecondary colleges and universities—as well as an online smorgasbord of credentials for personal subscriptions. For all of these, AI offers optimal procedures and curricula, increasingly the only way to keep up with exploding demand; thus, the proliferation of kinds of institutions, programs, curricula, courses and credentials is sure to continue.

The need for education will also increase, so the means of delivery and content in such a disturbed environment will require extraordinarily innovative creativity, resilience and agile adaptability among educators. The highest priority will have to be keeping up with the transformations—figuring out how best to insert the cultivation of humane values, best accomplished between human teachers (scholars, professors, practitioners) and learners, and provided by educational institutions and individuals, into the many new forms of training. Ensuring that this happens will be a major responsibility of today’s educational infrastructure and personnel, because AI does not, and does not have to, care about values. Will individual learners care? Not necessarily—for consumers of credentials, personal and even professional values apart from their commercial value are not a top priority. Whether employers will care about them is a major issue for concern by educators.

Here, the paradigm-shift in post-secondary education and training arises for attention by umbrella organizations like, for example, NEBHE and this journal. When NEBHE was founded, in 1955, the dominant paradigm in post-secondary education was referred to simply as “higher” education” (the “HE” in those acronyms)—residing in liberal arts colleges (including community colleges) and universities. The New England governors, realizing that the future prosperity of our region would be heavily dependent on “higher” education, committed their states to the shared pursuit of academic excellence in which New England was arguably the national leader.

That simple paradigm, however, has been superseded in practice. Today, the much greater variety of institutional forms and procedures, much more heavily reliant on rapidly developing technology, and the recognized need for broader inclusion of previously neglected and disadvantaged populations, calls for reconceptualization and rewording, reflecting the broader new reality of post-secondary, lifelong, continuing education and training.

New England is no longer the generally acknowledged national leader in this proliferation; the paradigm-shifting is a nationwide phenomenon. Nonetheless, though the rationale for a New England regional umbrella organization for both educational and training infrastructure has been transformed, it persists. Now it is needed to help the two branches of post-secondary human and skills development work in mutually reinforcing ways, despite the challenges—which are accelerating and growing—for both branches. Lifelong continuing education and training will be enriched, strengthened and refined by their complementary collaboration for all demographic constituencies.

How this might happen among an increasing variety of institutions still needs to be worked out in this highly fluid and dynamic environment. That is the urgent challenging mission and responsibility of the umbrella organizations. At the ground-level, individual professionals need to be reassessing their jobs defensively in humanistic directions, for which they will be fortified with a strategic sense of mission as a crucial element in the comprehensive infrastructure. Beyond that, coordinated organization will help form multiple alliances among institutions in a united front against encroaching AI robotization. This may be the only pathway for retaining roles and responsibilities by humans into the future.

George McCully is a historian, former professor and faculty dean at higher education institutions in the Northeast, professional philanthropist and founder and CEO of the Catalogue for Philanthropy.

Even before germ theory

“Believing it to be the root of all human ills, our {New England} forefathers avoided drinking water whenever possible…. {In} the early days, family brewing was as important as family baking… and every housewife had her favorite recipes.’’

— Ella Shannon Bowles and Dorothy S. Towle, in Secrets of New England Cooking (1947)

‘Light and metaphor’ in New England

“Forest Sunset" (pastel on paper), by Anne Emerson, in her show “Sinking Into Nature,’’ at Creative Connections Gallery, Ashburnham, Mass., starting Nov. 5.

Ms. Emerson says in her Web site:

“I am a New England painter and a writer. The two actions seem to me to feed each other, opening me to see the world simultaneously in light and metaphor. I paint what pleases me and what moves me. My paintings are of people, things and places I love, and most of my paintings have personal historical references. The act of painting is a meditation for me, awakening me to ‘all this joy and beauty,’ in the words of my grandmother's favorite prayer. In a way my painting is also an act of longing. It is an effort to capture the extraordinary feeling of being held in a natural place or emotion, suspended in beauty, power, solitude and light.’’

Ashburnham Town Hall

— Photo by John Phelan

Mike Freeman: The mysterious and alarming decline of muskrats - much needed waterway engineers

Muskrat feeding.

— Photo by mikroskops

No one would call muskrats “charismatic megafauna.” They’re pudgy, small and just rat-like enough. Semiaquatic, they inhabit sloughs, creeks, and swamps people rarely visit. Muskrats have been considered so prevalent and unremarkable that even people in tune with environmental goings-on have been unaware of the species’ 50-year decline. Biologists noted the nationwide trend early through trappers’ harvest data, but earnest study is a recent phenomenon.

“It would be like robins suddenly declining,” said John Crockett, a University of Rhode Island graduate student studying the state’s muskrat distribution. “No one ever thought muskrats would be in trouble.”

Muskrat lodge built from vegetation

In trouble they are, though, with unsettling implications. The first of these are the animals themselves and their ecological role. Muskrats feed on wetland vegetation and build covered winter “lodges” from it. This opens wetlands up, thinning plants such as cattails and bulrushes to create what Crockett called “patchy ecosystems” that sustain greater biodiversity, the way big wind events, pest outbreaks, and managed timber cuts open forests to new growth, attracting different suites of birds and plant communities than uniform woodlands.

With dwindling muskrat populations, dense vegetation blunts water flow, changes oxygen levels, and can pare back fish and invertebrate life.

“Muskrats are crucial wetland engineers,” said Laken Ganoe, another URI Ph.D. candidate, who published a 2020 paper on muskrat decline while at Penn State. “Similar to beavers, their activity can change hydrology, stream bank structure, and help maintain functioning wetlands. They’re also a key prey source for species such as mink, birds of prey, and raccoon. The wetlands they help maintain provide ecosystem services such as water filtration and air purification, and declining muskrat populations can throw these out of balance.”

In southern New England, muskrats inhabit fresh and brackish water, from nameless rills to big rivers to salt marshes. Their increasingly diminished presence is bad enough, but equally worrisome is why it is happening, in large part because that isn’t known.

Laurence C. Smith of the Institute at Brown (University) for Environment and Society has started a DNA study to determine muskrat presence in Rhode Island waterways. He described the current science, which isn’t far beyond the spit-balling phase.

“Researchers are just beginning to study this problem and there are numerous hypotheses being tested, including disease, habitat loss, and climate change,” he said.

Crockett added nuance, saying that habitat fragmentation and isolation are plagues for all species including muskrats, and that ecosystem degradation, including water quality, is another potential culprit. Ganoe’s Pennsylvania study looked at traditional muskrat diseases such as tularemia, along with ailments that might relate to cyanobacteria and legacy industrial chemicals. While she found various levels of concern, nothing resembling a widespread killer turned up. Across the United States and Canada, she said, there seems to be consensus that “there’s not one overarching cause of the decline, but rather a dozen puzzle pieces working in conjunction.”

That muskrats’ woes result from a grim grab bag of sprawl, industry, pollution and climate change is likely, which only compounds the worry, as muskrats have already proven that they are built for the Anthropocene. Highly prolific and mobile, the animals thrived in the notoriously unregulated mid-20th Century, but are listing now. Why is unknown, but muskrats once rated with pigeons and cockroaches as the creatures most likely to survive us, so finding that answer is imperative.

Trapper harvest data isn’t infallible, but biologists gain much from it. Charlie Brown, the Rhode Island Department of Environmental Management’s recently retired furbearer biologist, studied harvest data throughout his 31-year professional tenure.

“It’s difficult to rely on harvest data exclusively,” he said. “But it’s valuable. Rhode Island requires exact harvest data in order to renew your license … whereas that information is voluntary in other states, so we have very specific numbers going back to 1949.”

In the 1950s, Brown said, Rhode Island trappers took 10,000 muskrats a year. During the 2019-2020 season, just 47 were killed. Declining trapper numbers affect that, but not enough for a drop that steep.

There’s some counter-intuition to wrestle here. On paper, conditions favor muskrats more now than in the 1950s to ’70s, when wetlands were blithely drained and factories dumped effluent everywhere. In Barrington, R.I., where Brown grew up, a lace dye company made Bullocks Point Cove turn whatever color stain it used that day.

“But muskrats were still there,” Brown said. “And in big numbers.”

Crockett said even today one of the highest muskrat concentrations he has found is on the Pawtuxet River right under Interstate 95.

Wetland acreage, too, has remained stable during the muskrats’ decline period. That marshes are no longer drained and rivers no longer run purple is great news. Yet, muskrats boomed during these conditions and badly falter now.

With research just ramping up, speculation remains the only map. Waters are still loaded with farm and lawn runoff, along with plastic pollution, though no direct evidence currently links these with muskrat decline. Invasive aquatic flora jumps out, too. Smith is testing the replacement of native plants like cattails (Typha) by phragmites, the invasive reeds that now dominate fresh and brackish waters.

“Phragmites creates more sterile wetlands and chokes out open-water patches favored by muskrats,” he said.

Laura Meyerson, a URI professor whose research focuses on invasive species, with a particular emphasis on plants, points to phragmites and other invasive flora as potential reason for muskrat decline.

“Water chestnut is particularly nasty,” she said. “It grows floating mats that have little nutritional value. In fresh and salt water, phragmites has outcompeted Typha. Muskrats rely on Typha for their carbohydrate-rich rhizomes [roots] and the leaves and stems to build their lodges.”

Mike Freeman is an ecoRI News contributing reporter.

‘The Yankee-est gal’

Better Davis (at age 79) in The Whales of August (1987), which brought her acclaim during a period in which she was beset with failing health and other personal crises. The movie is set in Maine.

“To fulfill a dream, to be allowed to sweat over lonely labor, to be given the chance to create, is the meat and potatoes of life. The money is the gravy. As everyone else, I love to dunk my crust in it. But alone, it is not a diet designed to keep body and soul together.’’

— Bette Davis (1908-1989), movie star and writer, in her 1962 memoir The Lonely Life

She called herself the “Yankee-est gal who ever came down the pike.”

She was born and educated in Massachusetts, married three New Englanders and had homes in Massachusetts, New Hampshire and Maine.

‘Partners in this land’

An Eastern Garter Snake, New England’s most common snake.

“I put out my hand and stroke

the fine, dry grit of their skins.

After all,

we are partners in this land,

co-signers of a covenant.

At my touch the wild

braid of creation

trembles.’’

— From “The Snakes of September,’’ by Stanley Kunitz (1905-2006). A U.S. poet laureate, Mr Kunitz, who grew up in Worcester, divided much of his time between New York City and Provincetown, where he had a famous garden.

Tips for New England gardeners in drought

From ecoRI News (ecori.org)

For backyard gardeners, mild droughts and water-ban restrictions common during the summer can be a cause for concern. Kate Venturini Hardesty, a program administrator and educator with the University of Rhode Island’s Cooperative Extension, offers some tips for gardeners who are feeling the heat.

Let your lawn rest.

“Your lawn is on summer vacation,” she said. “Lawns are meant to go dormant in July and August. Many turf types are perennial species, so they rely on a break, much like the herbaceous perennials in our gardens. When we don’t allow them to rest, they’re weaker, just like you and I without a good night’s sleep. Refraining from watering the lawn saves a tremendous amount of water.”

While this may mean that your lawn is brown instead of a vibrant green, it will be beneficial for its overall health.

Don’t mow your lawn too low.

Mowing your lawn too far down will also have a negative impact on it. You don’t want to be the golf course of your neighborhood — the taller your grass is, the healthier it will be.

“The higher your mower is set, the deeper the roots are able to go underground to access soil moisture,” she said.

Water your crops and gardens as early in the day as possible.

“Don’t water any time but the morning,” she said. “It gives the plants some time to actually absorb the water before it evaporates.”

If you water at noon, you’ll lose a bunch of water to evaporation. If you water in the evening after the sun has set, you run the risk of causing fungal issues for your plants.

Know what plants are best for your garden.

When it comes to designing and planning your gardens and landscaping, it’s critical that you know which plants are the best suited for your space. Plants that are native to your area will generally do best because they evolved and are able to adapt to the way your local climate is changing on both the micro and macro levels.

The types of plants that are best to plant vary from garden to garden based on a variety of factors, including sun exposure, solid health, and drainage. Before you plant, do your research.

“A simple site assessment exercise can help you gather information about available sunlight and water, wind exposure, drainage and soil health,” she said. “The more information you have, the easier it is to choose plants that can tolerate the climate on your site.”

Venturini Hardesty said that, on average, New England tends to get about 45 inches of rain annually. If the average rain per week is about an inch, that leaves about seven weeks without rain, which happens to be almost the full length of the months of July and August.

The shifts that climate change will bring to backyard gardeners – and crop growing and planting as a whole – will need to be dealt with on a regional level, not in individual backyards, she said.

"CHIPS Act'' seen as boon for New England

Virtual detail of an integrated circuit through four layers of planarized copper interconnect, down to the polysilicon (pink), wells (grayish), and substrate (green).

The Semiconductor Industry Association says that Massachusetts annually exports $2.7 billion worth of semiconductors and machinery used to make semiconductors — making it the third most valuable export from the commonwealth.

James T. Brett, CEO and president of the New England Council, (newenglandcouncil.com) recently wrote in a Providence Business News op-ed:

“The New England Council was proud to support the ‘CHIPS and Science Act’ {recently passed by Congress) and we believe that its passage is a huge win for the New England innovation economy….

“Semiconductors enable the key technologies driving the future economy and our national security, including artificial intelligence, 5G/6G, quantum computing, cloud services, and more. The New England region is home to a number of semiconductor manufacturers – including industry leaders like Analog Devices and Texas Instruments – as well as wide array of technology businesses who rely on semiconductors to support their businesses….

“Beyond this vital support for the semiconductor industry, this legislation also makes several other important investments in that will support continued growth in the New England innovation economy. The bill authorizes $81 billion in funding over five years for the National Science Foundation (NSF) to support STEM education, establish regional technology hubs, and support a new technology directorate that aims to turn basic research breakthroughs into real-world applications. New England is of course home to some to some of the world’s leading research institutions, and received nearly $800 million in NSF funds in 2021…. Our region will undoubtedly benefit from this additional infusion of NSF funding….’’