Beats thinking

“Muscle Memory” (monoprint drypoint construction with violin and mirror), by Massachusetts artist Debra Olin, at Brickbottom Artists Association’s (Somerville, Mass.) members show, through Nov. 19.

Must be patrolled

“Island of Endangered Species” (oil, mixed media, fabric on panel), by Donald Saaf , his show “Peaceable Kingdom: The Art of Donald Saaf,’' at the Cahoon Museum of American Art, Cotuit, Mass., through Dec. 23. He lives in the Saxtons River section of Rockingham, Vt.

— Photo by Mr. Saaf

The museum says Mr. Saaf:

"{E{}xplores the subtle line between fine art and folk art in paintings that are heartwarming and approachable. His large-scale paintings and collages draw upon his memories of nature, family and community from his life in rural Vermont.’’

‘Transcendent shapes’

“Remains” (1970) ( sand and gel medium), by Merrimac, Mass.-based artist Rhoda Rosenberg, in her show “Shapes of Time: 1968-2022,’’ at Concord Art, Concord, Mass., through Dec. 17.

The gallery says:

“Rosenberg’s work focuses on deeply rooted ties with family members and the power of an object’s shape to convey feeling. Concerned with emotion and meaning behind her subject matter more than representational rendering, she has concentrated on transcendent shapes throughout her career, seeing beyond the form of an object and getting to the feeling it evokes instead.’’

Merrimac Town Hall near Merrimac Square

— Photo by Doug Kerr

David Warsh: Claudia Goldin's Nobel Prize was for many reasons

Claudia Goldin

SOMERVILLE, Mass.

The award of any Nobel Prize is an invitation to go prowling through the past. In the case of Claudia Goldin, of Harvard University, born in 1946, the history on offer is that of an entire generation – not just one crucial generation, in fact, but three. Hers is the first fifty-year career by a woman in major league economic research since that of Joan Robinson (1903-1983). Perhaps not since John Nash shared the prize, in 1994, has a single life in economics been so intricately connected to the context of its times as that of Goldin.

Calling Sylvia Nasar, author of the Nash biography, A Beautiful Mind!

For one thing, Goldin is a third-generation Nobel laureate. She wrote her dissertation under the direction of economic historian Robert Fogel, of the University of Chicago, who wrote his under Simon Kuznets, of Johns Hopkins University (in Goldin’s case, with significant influence by labor theorist Gary Becker as well.)

For another, she lived the full University of Chicago experience, before escaping to a place of her own. Some years ago, she told Douglas Clement, of the Federal Reserve Bank of Minneapolis, that her Cornell undergraduate mentor, Fred Kahn (who later became Jimmy Carter’s economic adviser), discouraged her from going.

“When I went to Cornell, the room that I entered was filled with paintings and good food. But Chicago was a castle, a completely different universe. I walked in and realized, once again, that I knew nothing. Now I knew absolutely nothing.… [She had gone to study industrial organization with George Stigler.] And then Gary [Becker] arrived, and once again I realized that the world of economics was much larger than I had thought. Gary was doing brilliant work on many different issues that I would call the economics of social forces. And then, to make things even better, I met Bob Fogel … [who] mesmerized me with economic history, and that combined my liberal arts junkie taste with my more rigorous math sensibilities.”

There followed twenty years of professional turbulence. After top-tier Chicago, she spent two years at third-tier Wisconsin, followed by six years in a top-ranked Princeton department, before settling down to tenure at the second-tier University of Pennsylvania. These were years when the Committee on the Status of Women in the Economics Profession was organizing, decades in which women began going to law and medical schools in significant numbers, but advances came much more slowly in economics.

Goldin’s major phase began in 1990, when she was appointed Harvard’s first tenured female professor of economics. She published Understanding the Gender Gap: An Economic History of American Women the same year, and was named director of the program on the Development of the American Economy of the National Bureau of Economic Research. Since then, nobody has written more thoughtfully and imaginatively about the myriad economic complexities of female gender in and out of the labor force, culminating in Career & Family: Women’s Century-Long Journey toward Equity (Princeton, 2021).

There is, as well, a love story. Goldin married her fellow Harvard economist Lawrence Katz, a labor economist. Over the course of several years, the pair produced an important and heavily documented study of the rise of the high-school movement in the United States in the late 19th Century, designed to prepare workers for an emerging industrial economy. The Race between Education and Technology Society (Harvard Belknap, 2009) is routinely cited among their most enduring contributions. In most respects, Katz is not a trailing spouse; earlier this month he was elected president of the American Economic Association.

Peter Fredriksson, of the University of Uppsala, a member of the committee that recommended the prize to Goldin, described last week several years of hard work as committee members untangling one contribution from the many others that warranted recognition. In the end, he said, they settled on the combination of economic history and labor economics that produced a U-shaped portrait of the changing trade-off between careers and family. Per Kussell, professor at Stockholm University and secretary to of the committee, emphasized “The prize is not the person, it’s for the work.”

Yet in this case, the person is equally interesting. I don’t know any of the details. But I am fairly certain Goldin’s is an unusually good story. Her prize was overdetermined, in that it was awarded for many overlapping reasons. For more than a decade it was understood that it eventually would be given. Better sooner than later. It makes a fitting climax to the story of one generation and the rising of the of the next.

David Warsh, a veteran columnist and an economic historian, is proprietor of economicprincipals.com, where this essay originated.

Team player

“Portrait of Daniel King: Scouting for Men and Boys” (linocut, wood cut, lithograph), by Mark Sisson, in the group show “50/50: Collecting the Boston Printmakers,’’ at the Art Complex Museum, Duxbury, Mass., through Jan. 14.

Llewellyn King: As the electricity sector is reinvented, there's an urgent need for engineers and technicians to support them

At the new (founded 1997) but already highly prestigious Olin College of Engineering, in Needham, Mass.

WEST WARWICK, R.I.

I have a soft spot for engineers and engineering. It started with my father. He called himself an engineer, even though he left school at 13 in a remote corner of Zimbabwe (then called Southern Rhodesia) and went to work in an auto repair shop.

By the time I remember his work clearly, in the 1950s, he was amazingly competent at everything he did, which was about everything that he could get to do. He could work a lathe, arc weld and acetylene weld, cut, rig, and screw.

My father used his imagination to solve problems, from finding a lost pump down a well to building a stand for a water tank that could supply several homes. He worked in steel: African termites wouldn’t allow wood to be used for external structures.

Electricity was a critical part of his sphere; installing and repairing electrical-power equipment was in his self-written brief.

Maybe that is why, for more than 50 years, I have found myself covering the electric-power industry. I have watched it struggle through the energy crisis and swing away from nuclear to coal, driven by popular feeling. I have watched natural gas, dismissed by the Carter administration as a “depleted resource,’’ roar back in the 1990s with new turbines, diminished regulation, and the vastly improved fracking technology.

Now, electricity is again a place of excitement. I have been to four important electricity conferences lately, and the word I hear everywhere about the challenges of the electricity future is “exciting.”

James Amato, vice president of Burns & McDonnell, a Kansas City, Mo.-based engineering, construction, and architecture firm that is heavily involved in all phases of the electric infrastructure, told me during an interview for the television program White House Chronicle that this is the most exciting time in supplying electricity since Thomas Edison set the whole thing in motion.

The industry, Amato explained, was in a state of complete reinvention. It must move off coal into renewables and prepare for a doubling or more of electricity demand by mid-century.

However, he also told me, “There is a major supply problem with engineers.” The colleges and universities aren’t producing enough of them, and not enough quality engineers — and he emphasized quality — are looking toward the ongoing electric revolution, which, to those involved in it, is so exhilarating and the place to be.

This problem is compounded by a wave of age retirements that is hitting the industry.

I believe that the electricity-supply system became a taken-for-granted undertaking and that talented engineers sought the glamor of the computer and defense industries.

Now, the big engineering companies are out to tell engineering school graduates that the big excitement is working on the world’s biggest machine: the U.S. electric supply system.

My late friend Ben Wattenberg, demographer, essayist, presidential speechwriter, television personality, and strategic thinker, hosted an important PBS documentary film and co-wrote a companion book, The First Measured Century: The Other Way of Looking at American History. He showed how our ability to measure changed public policy as we learned exactly about the distribution of people and who they were. Also, how we could measure things down to parts per billion in, say, water.

In my view, this is set to be the first engineered century, in tandem with being the first fully electric century. We are moving toward a new level of dependence on electricity and the myriad systems that support it. From the moment we wake, we are using electricity, and even as we sleep, electricity controls the temperature and time for us.

The new need to reduce carbon entering the atmosphere is to electrify almost everything else, primary transportation — from cars to commercial vehicles and eventually trains — but also heavy industrial uses, such as making steel and cement.

Amato said there is not only a shortage of college-educated engineers needed on the frontlines of the electric revolution but also a shortage of competent technicians or those trained in the crafts that support engineering. These are people who wield the tools, artisans across the board. In the electric utilities, there is also a need for line workers, a job that offers security, retirement, and esprit.

In the 1960s, the big engineering adventure was the space race. Today, it is the stuff that powers your coffeemaker in the morning, your cup of joe, or, you might say, your jolt of electrons.

On Twitter: @llewellynking2

Llewellyn King is executive producer and host of White House Chronicle, on PBS, and is based in Rhode Island and Washington, D.C.

Editor’s note: Readers should read about this Massachusetts-based company.

Columbus Day in Victorian Salem

Columbus Day in 1892 at the John Tucker Daland House, in Salem, Mass., long before Native Americans and sympathizers were well organized to educate the general public on how Western Hemisphere indigenous people suffered in many ways in centuries of European colonialization started by the Italian explorer Christopher Columbus. 1892 was before the bulk of Italian immigration to America. Italian-Americans were naturally big fans of the holiday, but it didn’t become an official federal holiday until 1971. Southern New England, of course, drew large numbers of Italian immigrants.

The Daland House, an imposing, Italianate structure designed by architect Gridley James Fox Bryant, is at 132 Essex St. in the Essex Institute Historic District and now owned by the fabulous Peabody Essex Museum as home for the Essex Institute.

The three-story brick house was originally built for John Tucker Daland, a prosperous merchant. The Dalands lived in the house until 1885, when the Essex Institute acquired it. It was then remodeled as offices by architect William Devereux Dennis (1847–1913) and in 1907 connected to the adjacent Plummer Hall (former home of the Salem Athenaeum).

‘Beauty of impermanence’

Work by North Adams-based artist Tom Schneider in his show “Ecstatic Gates,’’ at Bromfield Gallery, Boston, through Oct. 29.

The gallery says:

“Tom Schneider’s current series, ‘Ecstatic Gates,’ is a collection of 13 wall sculptures. Each piece is a miniature shrine or chapel and expresses the ethereal duality of the eternal and finite.

“Inspired by the beauty of impermanence, each piece incorporates bones, natural fibers, and decaying wood grains. The shimmer of gold peeking through the doors offers the suggestion of what lies beyond our world.

“Schneider’s sculptures are influenced by the elegant lines of Asian architecture and the Japanese aesthetic of wabi-sabi. They thereby honor imperfection, transience, the rawness of the natural world, and the beauty found in small and humble things.’

The Hoosic River runs through North Adams and was essential to its growth, providing power for the mills that were built along its banks as well as those of its branches. Many artists can be found in surviving mill buildings today.

The Norad Mill, in North Adams. The woolen factory was built in 1863 in an Italianate style and was added to the National Register of Historic Places in 1985.

— Photo by Beyond My Ken

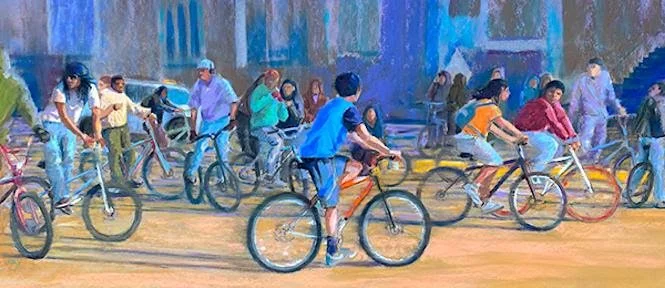

Bumping bikes

“Propelled” (pastel), by Plymouth, Mass.-based Jory Mason, in the group show “Signature Strokes,’’ at the South Shore Art Center, Cohasset, Mass., through Oct. 28., in collaboration with the Pastel Painters Society of Cape Cod and juror Lisa Flynn.

The arts center says the show features pastel artwork of “everything from natural scenes of plants, water and delicate flowers to subjects including men at work repairing a city street and the rough moorings of a ship.’’

Recreation of Plimoth Plantation, at Plymouth

— Photo by Marco Almbauer

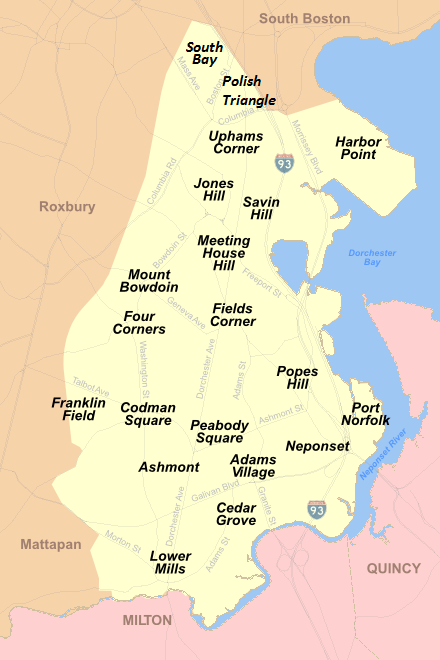

David Warsh: Dorchester's weekly paper plows on through the decades

SOMERVILLE, Mass.

Rupert Murdoch is stepping down as chairman of Fox and News Corp, having built the little Australian newspaper he inherited at the age of 21 (The News of Adelaide, circulation 75,000) into a global multi-media complex of enormous political influence. He is to be succeeded by his elder son.

Myself, I have been preoccupied recently with the saga of The Dorchester Reporter, which celebrated the 40th anniversary of its founding with an ebullient party in Boston on Sept. 14.

That “every banker has one good idea” is an old-time industry joke. Ed Forry’s good idea was to get out of the business. In 1983, at age 39, with banking deregulation accelerating, he quit his $24,000-a-year job as a savings bank executive to found a community newspaper in Boston’s largest neighborhood. Dorchester was then recovering from a decade of white flight to the suburbs,

Forry had some experience to start with: confirmed in St. Gregory’s Parish, he had graduated from Boston College High School and Boston College. As a community activist, he had written a column for the Dorchester Argus-Citizen, with which Forry had created a profitable yearbook business. His wife, Mary Casey Forry, would be an all-in partner. The couple had two young children and $5,000 in the bank.

The Reporter circulated monthly for several years. At first, advertising paid the way. The monthly went weekly, paid subscriptions were introduced, circulation grew. There were hard times. In 1993, as recession lingered, Forry laid off the entire staff of nine. Mary Forry died in 2004. By then, son Bill had joined the business, to become, eventually, executive editor and publisher. He married Linda Dorcena Forry, a Haitian-American who won election to the Massachusetts House of Representatives in 2005, then moved on to the state Senate, where she held a seat until 2018. For an account of those first 25 years, read the story by Boston Globe columnist Jack Thomas.

What is the business worth today? Decent livings for its eight fulltime staffers, paid gigs for its regular lineup of columnists and critics, and opportunities for interns and freelance writers. The paper has disproportionate political influence —-Boston Mayor Michelle Wu and U.S. Sen. Ed Markey spoke at the party — and retained earnings, and has considerably enhanced Dorchester pride.

xxx

In 1963, at the opposite end of the enterprise spectrum, a married couple of lawyers from Brooklyn saw promises in the California building boom and purchased the Golden West Savings and Loan Association in Oakland. In a go-go market of 1968, they made a public offering, Over the next 40 years, Herbert and Marion Sandler ran the most successful residential-mortgage lender in the country, until they sold the firm in 2006 at the top of the market for $24 billion to a North Carolina bank. Widely blamed – in their view unfairly – for the subprime housing-mortage crisis, they commenced a long-planned entry into the philanthropy business.

Among many other overtures, they called Paul Steiger, who for 16 years had been editor of The Wall Street Journal, which was just the being acquired by Rupert Murdoch. The result, in short order, was ProPublica, with an annual budget of $10 million, for the practice of WSJ-style investigative journalism.

Steiger hired as his successor Stephen Engleberg, an 18-year veteran of The New York Times. Effective fund-raising raising increased the annual budget to $40 million. So with a staff of a hundred or so well-seasoned journalists, ProPublica has established itself as the most successful of philanthropically endowed news organizations that have arisen among the ruins of the old advertising-supported metropolitan print press.

What’s the second-best nonprofit news organization? National Public Radio, at least in my view. And though it is reasonably well endowed, it has recently beginning a new fund-raising campaign. Lacking the same marriage of top newspaper cultures, its enterprise ventures in news are somewhat lower-key. And lacking undisputed foundational principles, it is susceptible to the regular political tempests that afflict Washington D.C.

xxx

Now back to Murdoch. How did he do it? Mostly by buying newspapers properties in down markets, then building them up experimentally instead of stripping them down. Fox News, which he founded in 1996, with former Richard Nixon pollster Roger Ailes, was a particular success; MySpace, an early competitor to Facebook, didn’t fair nearly as well.

Murdoch, 92, and in good health, has put his first-born son, Lachlan, in charge of all of the empire. But further struggles maybe in store. The mogul has three other children; they are entitled to equal shares under terms of his will. The conglomerate can be disassembled and shared out. But the conglomerate’s Wall Street Journal will probably power on.

That in turn leads to The Washington Post. When Donald Graham sold his family-controlled newspaper to Amazon founder Jeff Bezos for $250 million, in 2013, it was for far less than might have been offered by other bidders. Why was that? Consider that as one of the world’s richest men, Bezos possessed both the means and the moxie to restore one of America’s three leading newspapers to robust good health. Yet it can’t have escaped Graham’s attention, either, that Bezos has four children. Thus the Post’s independence will be preserved well into the future. That seems to have been a central aim of the public-spirited Graham.

Finally, that leads back to Boston. When the New York Times Co, sold The Boston Globe to Boston Red Sox owner John Henry, in 2012, for $70 million, having mismanaged the property for more than a decade, the direction of the paper itself fell to Henry’s wife, Linda, a native Bostonian. She has managed to keep it not just afloat, but interesting. It is profitable, she says, though print circulation continues to decline.

At a Globe conference on the new business last week, she spoke proudly of new bureaus in Rhode Island and New Hampshire. We’re not interested in becoming a national [paper],” she told listeners, “but as there’s been a decline in smaller regional places, we’re trying to fill that gap.”

In Dorchester, meanwhile, the money comes from putting newsprint on the front porch. The Dorchester Reporter probably out-influences the old Boston Herald, once owned by News Corp and now operated out of suburban Braintree by Media News Group, and, at least in municipal politics, often rivals The Globe itself.

David Warsh, a veteran columnist and an economic historian, is proprietor of Somerville-based economicprincipals.com, where this column originated.

Economicprincipals.com is a reader-supported publication. To receive new posts and support Mr. Warsh’s work, consider becoming a free or paid subscriber.

Mixing it up in Lynn

Delightfully bizarre view of Lynn, Mass., in 1881. It was a major manufacturing center, especially of shoes.

“I grew up about 30 minutes north of Boston in a town {Lynn, Mass.) that was a virtual melting pot - I was exposed to all different backgrounds, cultures, and religions, fueling my personal interests in global issues.’’

—- Alex Newell, (born 1992) , actor and singer

Alex Newell in 2015

Llewellyn King: Memories of people I knew from the Manhattan Project; beautiful "Barbie'

Important sites in the Manhattan Project. Alamogordo is where the first atomic bomb was detonated, on July 16, 1945. The map would have been better if it had included the site of uranium 238 refining for the project by Metal Hydrides Inc., in Beverly, Mass.

Edward Teller’s (1908-2003) badge photo at the Manhattan Project’s Los Alamos, N.H., facility. Called “The Father of the Hydrogen Bomb,’’ he was seen as an inspiration for the eponymous scientist in Stanley Kubrick’s classic 1964 black comedy Dr. Strangelove.

WEST WARWICK, R.I.

I have been to the movies. I haven’t done that since before the COVID shutdown.

I went to see two huge movies that have each grossed $1 billion so far, and I enjoyed them enormously. They are, of course, Barbie and Oppenheimer.

I went to see Barbie because I thought I should know what people were discussing. I went to see Oppenheimer because, in a sense, I have skin in that game. I knew a few people who worked on the Manhattan Project, and two of them were characterized in the movie: Hans Bethe and Edward Teller, known as the father of the hydrogen bomb.

About Barbie: It is a fantasy romp filled with popular, real-life messages. I had to see how director Greta Gerwig would make an adult movie about a doll, albeit a storied one — with brilliant imagination is how.

Oppenheimer, by contrast, is a major cinematic work, a remarkable recapturing of history and character development on the screen. Christopher Nolan is a director at the top of his game. He deserves a comparison with Orson Welles and David Lean.

Across the board, it is a triumph, compelling and true to the facts and the personalities. The evocative recreation of Los Alamos as it must have been, of the tower from which the first nuclear device was detonated, rings true. I have crawled all over the nuclear-test site and spent many hours at Los Alamos, where I used to give an annual lecture on energy or the relationship of humans to science.

In November 1975, Bethe and another veteran of the Manhattan Project, Ralph Lapp, and I put together a panel of 24 Nobel laureates (including Bethe) to defend civilian nuclear power. We got them all together on a stage at the National Press Club, in Washington. I had hoped that it would be a seminal event, ending some of the nonsense being spread about nuclear radiation.

Ralph Nader took up arms against us and assembled 36 Nobel laureates who were cool to nuclear. Ours were physicists, engineers and mathematicians who had a vast understanding of nuclear and endorsed it enthusiastically.

We didn’t win. Bethe, as I recall, was philosophical about being trounced.

I first met Teller in Geneva. I was to introduce him at a conference, and we had breakfast together. He seemed distracted and confused. But he was in top form when he spoke.

Later, I got to know him better. He gave a series of speeches for conferences I had organized on the Strategic Defense Initiative — colloquially known as Star Wars. He often sat slumped in his chair, clutching his enormous walking stick. But he stood erect on the podium, arguing vigorously the case for Ronald Reagan’s program.

The Oppenheimer movie reminded me of two institutions I covered intensely as a reporter: the Atomic Energy Commission (AEC) and its congressional overseer, the Joint Committee on Atomic Energy.

The committee was supposed to check the AEC. The AEC was a tool of the powerful and wildly pro-nuclear committee — the only joint committee empowered to introduce legislation in both houses of Congress. The reality of that partnership was that the committee proposed and the AEC disposed.

The movie is extraordinary in capturing the workings of Congress and how a nod or a smile can put great events in motion.

This understanding of the nuances and mores of Washington, and particularly the arcane theatricality of the congressional hearings, is accurate in ways seldom captured on film. This is more surprising given that the director is an Englishman who lives a very private life in Los Angeles.

I leave it to sociologists to ponder how two movies as different as Barbie and Oppenheimer could open simultaneously, becoming huge hits. If you see these movies, especially Oppenheimer, see them in the theater. They deserve that big-screen and wraparound-sound environment.

On Twitter: @llewellynking2

Llewellyn King is executive producer and host of White House Chronicle, on PBS.

White House Chronicle

17th Century creepiness

The House of Seven Gables, in Salem, Mass. The first part of the house was built in 1668.

“Halfway down a by-street of one of our New England towns stands a rusty wooden house, with seven acutely peaked gables, facing towards various points of the compass, and a huge, clustered chimney in the midst. The street is Pyncheon Street; the house is the old Pyncheon House; and an elm-tree, of wide circumference, rooted before the door, is familiar to every town-born child by the title of the Pyncheon Elm.”

— Nathaniel Hawthorne (1804-1864), in his novel The House of Seven Gables (1851)

Connecting kids with heart disease and horses

At Windrush Farm

Edited from a New England Council report (newenglandcouncil.com)

“Boston Children’s Hospital (BCH), in its treatment of patients with complex congenital heart disease, is connecting young children with horses to bolster their emotional and physical strength. The New England Council member has seen success with the unique program.

“Since 2017, BCH has partnered with Windrush Farm, in North Andover, Mass., to offer equine-assisted therapy to patients. The children have the opportunity to bond with and ride a horse, receiving the fulfillment of accomplishment. Additionally, patients receive many physical benefits, as riding trains their balance, strength, and flexibility. For these children who have battled with this disease since birth, there is great value in experiencing the confidence, assertiveness, and collaboration required in riding horses. Furthermore, the animals offer an emotional outlet, where patients can release the anxiety and stress that develops after a childhood affected by the disease.

“‘For kids who haven’t felt successful in much of their lives, this helps them build independence, confidence, and self-esteem,’ said Kate Ullman-Shade, the director of education for the cardiac neuro-developmental program at BCH. ‘I’ve had kids say to me, ‘I’m so proud of myself.’”’

David Warsh: Of economics ideas and the power of big business to shape policies

Theater lobby card for the American short comedy film Big Business (1924)

SOMERVILLE, Mass.

Merchants of Doubt: How a Handful of Scientists Obscured the Truth on Issues from Tobacco Smoke to Global Warming, by Nami Oreskes and Erik Conway, was a hard-hitting history in 2010 that catapulted its authors to fame – Oreskes all the way to Harvard University; Conway remained at the Jet Propulsion Laboratory at Caltech.

Their new book – The Big Myth: How American Business Taught Us to Loathe Government and Love the Free Market (Bloomsbury, 2023) – the authors describe as a prequel. In identifying the doubters, it exhibits the same strengths as before. It displays greater weaknesses in establishing the various truths of the matter. It is, however, a page-turner, a powerful narrative, especially if you are already feeling a little paranoid and looking for a good long summer read.

It’s all true, at least as far as it goes. Those three powerful intellects – Friedrich Hayek, Milton Friedman and Ludwig von Mises – started with unpopular arguments and won big. From the National Electric Light Association and the Liberty League in the Twenties and Thirties, the National Association of Manufacturers and the US Chamber of Commerce in the Fifties and Sixties, to the Federalist Society and the Club for Growth of today, business interests have been spending money and working behind the scenes to boost enthusiasm for markets and to undermine faith in government initiative.

To tell their gripping story of ideas and money, Oreskes and Conway rely on much work done before. Pioneers in this literature include Johan Van Overveldt (The Chicago School: How the University of Chicago Assembled the Thinkers who Revolutionized Economics and Business, 2007); Steven Teles (The Rise of the Conservative Legal Movement: The Battle for Control of the Law); 2008); Kim Phillips-Fein, (Invisible Hands: Hayek, Friedman, and the Birth of Neoliberal Politics, 2009); Jennifer Burns (Goddess of the Market: Ayn Rand and the American Right, 2009); Phillip Mirowski and Dieter Plehwe (The Road to Mont Pelerin: The Making of the Neoliberal Thought Collective, 2009); Daniel Rodgers (Age of Fracture, 2011); Nicholas Wapshott (Keynes Hayek: The Clash that Defined Modern Economics, 2011); Angus Burgin (The Great Persuasion: Reinventing Free Markets since the Depression, 2012); Daniel Stedman Jones (Masters of the Universe: Hayek, Friedman, and the Birth of Neoliberal Politics, 2012); Robert Van Horn, Phillip Mirowski and Thomas Stapleford, (Building Chicago Economics: New Perspectives on the History of America’s Most Powerful Economics Program, 2011); Avner Offer, and Gabriel Söderberg (The Nobel Factor: The Prize in Economics, Social Democracy, and the Market Turn, 2016); Lawrence Glickman (Free Enterprise: An American History, 2019); Binyamin Appelbaum (The Economists’ Hour: False Prophets, Free Markets, and the Fracture of Society) 2019); Jennifer Delton (The Industrialists: How the National Association of Manufacturers Shaped American Capitalism, 2020); and Kurt Andersen (Evil Geniuses: The Unmaking of America a Recent History, 2020). Biographies of Robert Bartley and Roger Ailes remain to be written.

So about those weaknesses? They boil down to this: In The Big Myth you seldom get the other side of the story. Take a fundamental example. Oreskes and Conway assert that “the claim that America was founded on three basic interdependent principles: representative democracy, political freedom, and free enterprise,” cooked up in the Thirties by the National Association of Manufactures for an advertising campaign. This so-called called “Tripod of Freedom” was “fabricated,” Oreskes and Conway maintain; the words free enterprise appear nowhere in the Declaration of Independence or the Constitution, they declare. That stipulation amounts to a curious “blind spot,” Harvard historian Luke Menand observed in a lengthy review in The New Yorker. There are mentions of property, though, writes Menand, “and almost every challenge to government interference in the economy rests on the concept of property.” See Adam Smith’s America: How a Scottish Philosopher Became an Icon of American Capitalism (Princeton, 2022), by Glory Liu, for elaboration.

Similarly, the previous Big Myth with which the market fundamentalists and the business allies were contending received little attention. As the industrial revolution gathered pace in the late 19th Century, progressives in the United States preached a gospel of government regulation. Germany’s success in nearly winning World War I received widespread attention. Britain emerged from World War II with a much more socialized economy than before. And in the U.S., government planning was espoused by such intellectuals as James Burnham and Karl Mannheim as the wave of the future.

Finally, The Big Myth largely ignores the experiences of ordinary Americans in the years that it covers. For all the fury that Big Coal mounted against the Tennessee Valley Authority, its dams were built, nevertheless. There is only a single fleeting mention of George Orwell, though his novels Animal Farm (1945) and 1984 (1949) probably influenced far more people than Hayek’s The Road to Serfdom. Paul Samuelson’s textbook explanation of the workings of “the modern mixed economy” dominated Milton Friedman’s Capitalism and Freedom tract for forty years and probably still does.

Yet there can be no doubt that there was a disjunction. Oreskes and Conway mention that in the ‘70’s conservative historian George Nash considered that nothing that could be described as a conservative movement in the mid-’40s, that libertarians were a “forlorn minority.” President Harry Truman was reelected in 1948, and Dwight Eisenhower, a moderate Republican, served for eight years after him. Suddenly. in 1964, Republicans nominated libertarian Barry Goldwater. Then came Richard Nixon, Gerald Ford, Jimmy Carter, Ronald Reagan, George H. W. Bush, Bill Clinton, George W. Bush, Barack Obama, Donald Trump and Joe Biden.

What happened? America’s Vietnam War, for one thing. Globalization for another. Massive migrations occurred in the US, Blacks and Hispanics to the North, businesses to the West and the low-cost South. Civil rights of all sorts revolutions unfolded, at all points of the compass. The composition of Congress and the Supreme Court changed all the while.

In Merchants of Doubt, Oreskes and Conway were on sound ground when making claims about tobacco, acid rain, DDT, the hole in the atmosphere’s ozone layer and greenhouse-gas emissions. These were matters of science, an enterprise devoted to the pursuit of questions in which universal agreement among experts can reasonably hope to be obtained. It was sensible to challenge the reasoning of skeptics in these matters, and to probe the outsized backing they received from those with vested interests. The interpretation of a hundred years of American politics is not science; much of it is not even a topic for proper historians yet. Agreement is reached, if at all, through elections, and elections take time.

Again, take a small matter, the interpretation of “the Reagan Revolution.” Jimmy Carter started it, Oreskes and Conway maintain; Bill Clinton finished it via the “marketization” of the Internet, and most persons have suffered as a result. It is equally common to hear it proclaimed that Reagan presided over an agreement to repair the Social Security system for the next fifty years, ended the Cold War on peaceful terms, and, by accelerating industrial deregulation, ensured on American dominance in a new era of globalization.

In arguments of this sort, EP prefers Spencer Weart’s The Discovery of Global Warming to Merchants of Doubt and Jacob Weisberg In Defense of Government: The Fall and Rise of Public Trust to The Big Myth. But I share Oreskes’ s and Conway’s concerns while searching for opportunities to build more consensus. A century after today’s market fundamentalists began their long argument with Progressive Era enthusiasts for government planning, sunlight remains the best disinfectant.

David Warsh, a veteran columnist and an economic historian, is proprietor of Somerville-based economicprincipals.com, where this column originated.

Pinnacle of puppetry

”Turkey Gobbler Balloon, Macy’s Thanksgiving Day Parade, 1929,’’ by German-American artist Tony Sarg (1880-1942), in the show “Tony Sarg: Genius at Play,’’ at the Norman Rockwell Museum, Stockbridge, Mass., through Nov. 5

— Photographer unknown, from the collection of the Nantucket Historical Association

The museum says:

The show “is the first comprehensive exhibition exploring the life, art and adventures of Tony Sarg, the charismatic illustrator, animator, puppeteer, designer, entrepreneur and showman who is celebrated as the father of modern puppetry in North America. His vast knowledge of puppet technology was instrumental in his design of the inaugural Thanksgiving Day parade balloon for Macy’s Department Store, in 1927, as well as subsequent parade balloons and automated displays for the company’s festive holiday windows, which were imitated nationwide. The creator of a host of popular consumer goods, from toys and clothing to home décor, Sarg also envisioned fanciful illustrated maps and created mural designs for the Oasis Cafe in New York’s Waldorf Astoria Hotel.’’

Sarg's “Nantucket Sea Serpent,’’ 1937.

— From the Nantucket Historical Association

The famed Austen Riggs Center, in Stockbridge, a mental hospital known for, among things, very quietly treating celebrities.

— Photo by Joe Mabel

Multi-faceted rapping

Work from the show “Nelson Stevens: Color Rapping,’’ at the D’Amour Museum of Fine Arts, Springfield, Mass., through Sept. 3.

The museum says:

“Nelson Stevens (American, 1938-2022), an artist and educator, is renowned for creating powerful, rhythmic compositions that celebrate Black life and reveal his technical mastery of the figure.’’

“Stevens lived in Springfield. In the early 1970s, {where} he initiated a groundbreaking public art project that resulted in the creation of over 30 murals throughout the city. Like Stevens’s colorful paintings, the murals promoted Black empowerment and brought the pride and activism associated with the Black Arts Movement to western Massachusetts. Fifty years later, his message, artwork, and influence continue to be celebrated locally and nationally.”

“I create from the rhythmic color-rappin-life-style of Black folk. I believe that art can breathe life, and life is what we are about.’’

— Nelson Stevens

Magical materials

“Dreams of Spring,’’ by Pat McSweeney, in the show “Greater Than the Sum of Its Parts,’’ at Galatea Fine Art, Boston, through Aug. 27. The artist is based in the Charlestown section of Boston.

The gallery says the show features the work of fiber artists who "create new visions" by "reinventing old techniques." The artists use "fabric, thread, wool, reeds, paper, wire and even plastic to create magic.’’

Beauty and bathos in The Berkshires

Mt. Greylock State Reservation (Greylock summit on the far right), in The Berkshires. At 3,491 feet, Mt. Greylock is the tallest point in Massachusetts. The shape of the mountain reminded Herman Melville of a whale as he was writing Moby Dick.

— Photo by Protophobic

Adapted from Robert Whitcomb’s “Digital Diary,’’ in GoLocal24.com

I drove out to The Berkshires last week for a couple of meetings. It brought back memories. In the late ‘50s’ I traveled there (by train from Boston!) to see relatives outside of Pittsfield in the little town of Richmond, and in the ‘70s I spent quite a few weekends staying with friends in a couple of towns along the Connecticut-Massachusetts line as an escape from New York City, where I was living and working.

One of my strongest recollections of the region is the election of 1970, when the Boston Herald Traveler (RIP) sent me to cover the vote in Berkshire County. I had little idea of how to go about that. So I first went to Pittsfield, the county seat and biggest town, and started walking around its then-busy downtown – lots of industry still around -- came across a radio station and went in to introduce myself. Unlike now, when most radio stations are owned by chains, many stations were locally owned and provided hefty doses of local news and other stuff from Berkshire communities.

I explained my plight to the station manager – ignorance – and he told me: “Don’t worry about it. We’ll bring you the vote tallies tonight. Would you like a donut and a cup of coffee? Take a look at The Berkshire Eagle’’ (a great local paper that still lives). He then gave me an overview of the county, including its reliance on General Electric and other big manufacturers that employed thousands of people, paid well and offered attractive fringe benefits. They also dumped large quantities of dangerous, cancer-causing chemicals into the region’s many rivers. The cleanups continue to this day.

My bosses in Boston were surprised that I was able to so quickly send them so much information that night….

Anyway, my recent trip reminded me that most of the county’s industrial base is gone.\

And so, increasingly the area has depended on tourism as well as on affluent people (most, apparently, from the New York City area) who have second homes there amidst the lovely hills and the region’s astonishingly large collection of cultural organizations. Here’s a few: Tanglewood (music), Jacob’s Pillow (dance), Shakespeare & Company (theater), the Clark, Berkshire, Williams College, and Norman Rockwell museums and the Massachusetts Museum of Contemporary Art. Route 7, in particular, is Culture Gulch.

Not surprisingly, the region has long drawn famous painters and writers. After all, much of it is beautiful, and it’s close to New York and Boston. (I love that Herman Melville saw the shape of a whale while gazing at Mt. Greylock from his house in Pittsfield, as he worked on Moby Dick.)

People are drawn from far and wide to such lovely towns -- if maybe a tad too precious/quaint to some people -- as Stockbridge, Lenox, Williamstown, and Great Barrington, with their fine 19th Century houses, fancy restaurants, art galleries, bookstores, weavers, health spas and big country estates. Private equity, hedge fund, and tech moguls have taken over some of the last, many built by “Robber Barons’’ from after the Civil War through the Roaring Twenties.

All these attractions, however, have helped raise housing costs by drawing rich people who have bid up property prices and made a living in the region unaffordable for many people who, decades ago, might have had good jobs in a local factory. But God bless a lot of the newcomers. Most aren’t showy -- they don’t want to be in the Hamptons or on Nantucket or Martha’s Vineyard --- and some give big bucks to charities in The Berkshires, a couple of civic leaders explained to me.

In any event, away from the spiffy towns are gritty and depressed ones, with closed stores and ramshackle housing. But Pittsfield, anyway, seems to be coming back from its long economic depression.

How to make the Berkshires prosperous for more people? The tourism/ hospitality businesses don’t pay well and are quite seasonal. The state is pushing for more pharmaceuticals-manufacturing plants, and state officials have said that they want to make Berkshire County a biotech hub. Really? And perhaps the region could ramp up its farming sector to take advantage of the public’s growing desire for more locally-grown food and for less reliance on huge agribusinesses far away. The Berkshires’ proximity to the huge Greater New York market is a plus. But the hilly terrain puts a limit on the size and number of farms, even as human-caused global warming extends the Berkshires’ growing season.

Global warming is also producing more flooding and other extreme weather events, as I was reminded early last week when I came upon some roads washed out by the same system that did such damage in Vermont. Torrential rain in hilly areas can be devastating, and such downpours are becoming more frequent. Local and state officials must push for new rules to discourage building in such potentially dangerous places as right along rivers. Reading about the disastrous flooding in such communities as Montpelier, Vt., last week reminded me of how strange it is that so much building has long taken place on riverbanks. Of course, people love being along water, and some of the original construction there were mills using waterpower, but at what cost now? Presumably, more and more insurers will stop writing property insurance in such vulnerable places, which will block a lot of waterfront buildings. That’s happening in many places along the coast as sea levels rise.

The Berkshires used to be a pretty important ski region, but not so much any more; the weather’s too unreliable and there are more environmental concerns about ski areas’ massive use of energy and water (for snowmaking) and erosion off the hills.

Much of Berkshire County, despite its bucolic reputation, is more exurban than rural. There are ugly malls with windswept parking lots in strips along roads without sidewalks and other depressing scenes of sprawl, some of which threaten water pollution. But local officials and the general population are more aware than they were just a few years ago of the need to control sprawl, by, among other ways, boosting public transportation and encouraging more housing density near the old downtowns, whose businesses would be helped by having more customers within walking distance.

Let’s hope that in the next few years, Berkshire County offers some edifying new examples of how to protect the scenic and cultural attractions of an area that’s so close to big cities, while also creating better jobs for year-round residents so that they aren’t compelled to leave.

Meanwhile, enjoy the glories of the Berkshires, where summer road traffic can be bad, but not nearly as bad as traffic along the coast, as I saw last Wednesday, when it took me almost an hour and a half to drive to Narragansett from Providence in bumper-to-bumper traffic there. Head for the hills, not the coast, in high summer, when millions want to visit New England all at once.

View from Main Street in Great Barrington (obviously) in the spring

—Photo by Anc516

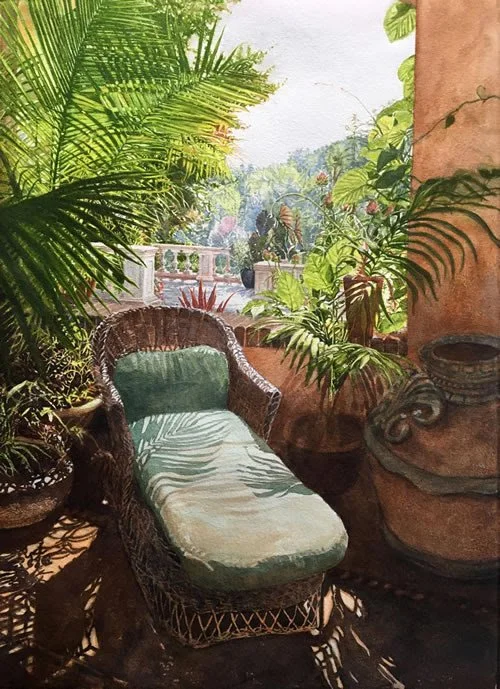

But beware the jungle

”Terrace Oasis” (watercolor), by West Barnstable, Mass.-based Brenda Bechtel, at the New England Watercolor Society Gallery’s 2023 “Celebrating New England’’ show, at the gallery, in Plymouth, Mass., through Sept. 7.

The gallery says:

“{The} exhibition … brings together 49 works from New England Watercolor Society members. The show is juried by Vladislav Yeliseyev, a Signature Member of the National Watercolor Society and the American Impressionist Society.’’

#Brenda Bechtel

#New England Watercolor Society