Performance anxiety

“Backstage” (oil on panel), by Jessica Gandolf, in her show “No Assembly Required,’’ at Moss Galleries, Falmouth, Maine, through April 5.

She says:

“Painting helps organize my thinking, my energy and my perceptions in a way that nothing else does. Seeing art has always made me want to make it. Creating art is a way of making sense of things, of saying something meaningful without words. Sometimes I seem to be calling attention to something at the edge of consciousness or dredging up something long buried. This can happen by making pictures or without using recognizable imagery. Sometimes it feels like magic is involved when uniting the physical presence of paint with the realm of the spirit -- magic born of some combination of anxiety and doggedness, open heartedness and luck.’’

Casco Bay from Falmouth in 191o.

A literary Hill

Window boxes on cobblestoned Acorn Street on Beacon Hill.

— Photo by Ian Howard

(Robert Whitcomb, New England Diary’s editor, is chairman of The Guardian. He edited but did not write this article.)

The imagery of Boston’s charming gas-lit streets and brownstone and brick Federal-style buildings have provided inspiration and residence to some of the most celebrated writers in American literature.

Beacon Hill, in particular, has been an historic home for greats, such as Louisa May Alcott, author of Little Women, and Nathaniel Hawthorne, author of The Scarlet Letter.

The neighborhood has been a source of vivid ink to others, such as Henry David Thoreau, who lived there in his childhood, and Robert Frost, who taught at Harvard University and other schools.

The loosely autobiographical Little Women, by Alcott, is a coming-of-age story about the overlap of childhood and young adulthood, a too swift liminal space where children want to be grown but are hesitant to grow up.

Alcott spent a considerable part of her early life in Boston from 1834 to 1840 before her family settled in Concord. However, she later returned to the city and lived on Beacon Hill in the early 1850s while working as a writer and a social reformer.

Her first published works, The Rival Painters: a Tale of Rome and Flower Fables were both published while she was living at 20 Pinckney Street. Her work as a women’s suffrage activist on Beacon Hill empowered her female characters with agency and self-determination.

Hawthorne, author of The Scarlet Letter, wrote love letters to his future wife from his home at 54 Pinckney Street while working at the Boston Custom House in the 1840s. Before that, he paid for room and board to the poet Thomas Green Fessenden on Hancock Street. He would later say of this period of his life, “I have not lived, but only dreamed about living.”

The heroine of his well-known novel grows beyond her longheld ideals after her Puritan community shuns her into isolation. Through protagonists that develop strong, individualistic approaches to the world,

Hawthorne and Alcott reflected the development of thoughts and views throughout a young adulthood which was spent in large part on Beacon Hill.

Many other authors and poets would have their brushes with Beacon Hill and Boston’s literary influence as well.

Henry James, renowned for the psychological depth of his approach to social complexities, lived at 102 Mount Vernon Street in the 1860s before moving to Europe. His time in Boston exposed him to the evolving nature of American society, a theme that permeates many of his works.

In the 20th Century, Beacon Hill continued to attract literary minds, including Sylvia Plath.

The renowned poet and novelist lived at 9 Willow Street while attending classes at Boston University and working at Massachusetts General Hospital. During her time on Beacon Hill, Plath was mentored by poet Robert Lowell and befriended fellow poet Anne Sexton. The city’s atmosphere and her personal experiences deeply influenced her work, particularly her novel The Bell Jar, which captures the struggles of a young woman navigating mental illness and societal expectations. The history of Beacon Hill is a testament to Boston’s enduring influence as a center of American literature.

These writers, among others, found inspiration in the city’s history, its people and its intellectual climate. Walking through the streets of Beacon Hill today, one can still feel the echoes of these literary greats, their presence lingering in the historic architecture and timeless charm.

Closing in on it

From the Norman B. Leventhal Map & Education Center, at the Boston Public Library:

“This {1785} map was the first American wall map, and among the most important early maps published in the United States. Due to a chronic lack of trained surveyors, engravers and printers in post-Revolutionary War America, very few maps of any kind were published before 1790.

“Using information from several earlier maps and coastal charts published in England, this map of the four New England states -- Massachusetts (including Maine counties), New Hampshire (including Vermont counties), Rhode Island, and Connecticut -- added substantial new information in the northern portions of the map, particularly for the New Hampshire townships and Maine's coastal area.

Creator:

Contributor:

Editor’s note: The big border vagueness at the top of Maine and New Hampshire was cleared up with Secretary of State Daniel Webster’s 1842 negotiations with the United Kingdom.

Childhood’s light and Dark

“Shadows” (archival inkjet print), by Anastasia Sierra, at the Cambridge Art Association.

Martin Abel/Reed Johnson: Is this a Bad sign for Human creativity?

From The Conversation, except for images at the top and bottom

Martin Abel is an assistant professor of economics at Bowdoin College. Reed Johnson is a senior lecturer in Russian, East European and Eurasian Studies at Bowdoin.

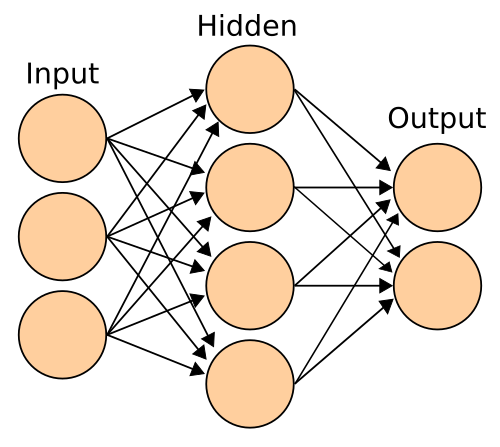

An artificial neural network is an interconnected group of nodes, akin to the vast network of neurons in the human brain.

The authors do not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organization that would benefit from this article, and have disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

People say that they prefer a short story written by a human over one composed by artificial intelligence, yet most still invest the same amount of time and money reading both stories regardless of whether it is labeled as AI-generated.

That was the main finding of a study we conducted recently to test whether this preference of humans over AI in creative works actually translates into consumer behavior. Amid the coming avalanche of AI-generated work, it is a question of real livelihoods for the millions of people worldwide employed in creative industries.

To investigate, we asked OpenAI’s ChatGPT 4 to generate a short story in the style of the critically acclaimed fiction author Jason Brown. We then recruited a nationally representative sample of over 650 people and offered participants $3.50 each to read and assess the AI-generated story. Crucially, only half the participants were told that the story was written by AI, while the other half was misled into believing it was the work of Jason Brown.

After reading the first half of the AI-generated story, participants were asked to rate the quality of the work along various dimensions, such as whether they found it predictable, emotionally engaging, evocative and so on.

We also measured participants’ willingness to pay in order to read to the end of the story in two ways: how much of their study compensation they’d be willing to give up, and how much time they’d agree to spend transcribing some text we gave them.

So, were there differences between the two groups? The short answer: yes. But a closer analysis reveals some startling results.

To begin with, the group that knew the story was AI-generated had a much more negative assessment of the work, rating it more harshly on dimensions like predictability, authenticity and how evocative it is. These results are largely in keeping with a nascent but growing body of research that shows bias against AI in such areas as visual art, music and poetry.

Nonetheless, participants were ready to spend the same amount of money and time to finish reading the story whether or not it was labeled as AI. Participants also did not spend less time on average actually reading the AI-labeled story.

When asked afterward, almost 40 percent of participants said they would have paid less if the same story was written by AI versus a human, highlighting that many are not aware of the discrepancies between their subjective assessments and actual choices.

Why it matters

Our findings challenge past studies showing people favor human-produced works over AI-generated ones. At the very least, this research doesn’t appear to be a reliable indicator of people’s willingness to pay for human-created art.

The potential implications for the future of human-created work are profound, especially in market conditions in which AI-generated work can be orders of magnitude cheaper to produce.

Even though artificial intelligence is still in its infancy, AI-made books are already flooding the market, recently prompting the authors guild to instate its own labeling guidelines.

Our research raises questions whether these labels are effective in stemming the tide.

What’s next

Attitudes toward AI are still forming. Future research could investigate whether there will be a backlash against AI-generated creative works, especially if people witness mass layoffs. After all, similar shifts occurred in the wake of mass industrialization, such as the arts and crafts movement in the late 19th Century, which emerged as a response to the growing automation of labor.

A related question is whether the market will segment, where some consumers will be willing to pay more based on the process of creation, while others may be interested only in the product.

Regardless of how these scenarios play out, our findings indicate that the road ahead for human creative labor might be more uphill than previous research suggested. At the very least, while consumers may hold beliefs about the intrinsic value of human labor, many seem unwilling to put their money where their beliefs are.

View of the Bowdoin campus from Coles Tower.

Photo by Polarbear 11

To get me Out

“Chasing The Horizon” (acrylic, ink, fake fur, cotton on wood panel), by Yeon Ji Yoo, in the show “Wish You Were Here,’’ opening March 22 at the Brattleboro (Vt.) Museum & Art Center.T

Brutal!

Part of the University of Massachusetts at Dartmouth campus, which was designed by Paul Rudolph.

Boston City Hall, designed by Michael McKinnell and Gerhard Kallmann

Photo by andrewjsan - https://www.flickr.com/photos/andrewsan/6776358460/

Adapted from an item in Robert Whitcomb’s “Digital Diary,’’ in GoLocal24.com

The Brutalist, the epic movie about an immigrant architect and Holocaust survivor, has aroused a lot of interest in “Brutalist” architecture, whose heyday was from the 1950’s to the early ‘70s. It’s characterized by minimalist and bulky constructions displaying bare materials, most notably exposed and unpainted concrete or brick, angular shapes and little if any decoration. Brutalism, with its cheap materials and speed of building, was particularly attractive to those rebuilding Europe’s bombed-out cities after World War II.

When I think back to what I walked by in various cities back then, those then-new gray and hulking creations, some with pipes and other utilities exposed, often come to mind.

Some of these buildings are, or were when they went up, quite exciting, even Boston’s famous or infamous city hall, which went up in 1968, or the campus of the University of Massachusetts at Dartmouth, built in the mid and late ’60s. But more people consider them dystopian than beautiful. They also tend to leak! And a big problem is that concrete walls don’t age well, especially in damp climates such as New England’s. The concrete tends to collect dirt and stain, and its heaviness weighs on our spirits. Of course, granite, marble and other rock walls look heavy, too, but they can be very beautiful, if expensive.

Most people want some texture, charm and warmth in their built environments – say with weathered brick and wood, seasoned with sometimes quirky decoration, some of it criminally cute. They want to be comforted by the built environments they live amongst. That isn’t to say that they can’t see the beauty in such gorgeous glassy, glittery Modernist (but not Brutalist) creations as the John Hancock Tower in Boston or New York’s Seagram Building and Lever House. (I loved to look at them by day or night when I worked in New York in the ‘70’s.)

In any event, Brutalism has had its run, which all in all is a good thing, though some of the “Post-Modernist’’ architecture that has succeeded it since the 80’s is hackneyed, with pastiches of various styles, newish and ancient, looking glued together.

A stripped-down Post-Modernist building at Dartmouth College, in Hanover, N.H. Completed in 2002, it was designed by Venturi, Scott Brown and Associates, Inc. in association with Shepley Bulfinch Richardson and Abbott. Its style references Georgian architecture, the dominant look of buildings on the campus.

AKA St. Patrick’s Day

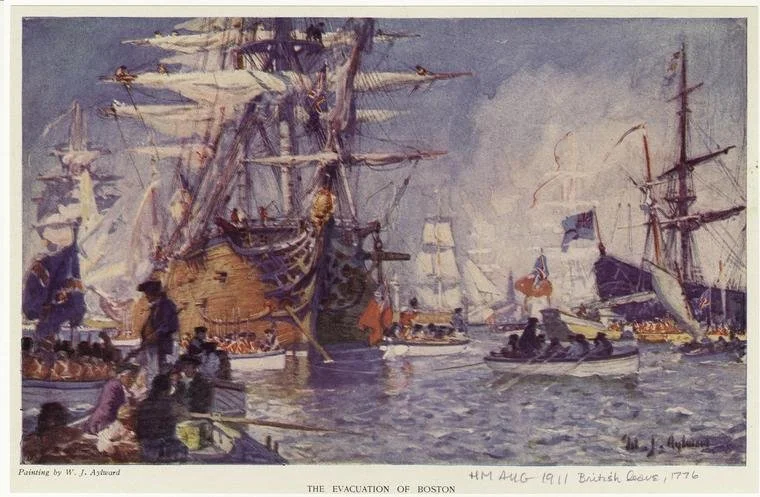

The evacuation of Boston by the British, on March 17, 1776. That, and not St. Patrick, is why it’s an official holiday in Suffolk County, Mass.

— Painting by William James Aylward

Is it your Servant or Master?

P.T. Barnum

“Money is in some respects like fire; it is a very excellent servant but a terrible master. When you have it mastering you; when interest is constantly piling up against you, it will keep you down in the worst kind of slavery. But let money work for you, and you have the most devoted servant in the world.’’

— P.T. Barnum, (1810-1891), of Bridgeport, Conn. (where he served as mayor), American showman and politician famous for promoting celebrated hoaxes and founding with James Anthony Bailey what became known as the Ringling Bros. and Barnum & Bailey Circus. He was also an author, publisher and philanthropist, but said of himself: “I am a showman by profession ... and all the gilding shall make nothing else of me."

‘between hand-made and mass-Produced’

“Snulpture #4” (welded steel, fabric, audio and kinetic electronics), by Andrew Zimmerman, in his show “Snulpture,’’ at Boston Sculptors Gallery, opening April 3.

He says:

“In my work I am interested exploring the intersection between painting and sculpture, art and design, the hand-made and the mass-produced. I am excited by the tension that arises from situating my work in between these categories. I would like my paintings to create moments of unexpected discovery within a language of reconstructable forms.

“I fondly remember working with my dad in his wood shop as a young child. Cutting the parts and assembling the pieces into a bench or a table revealed to me a magical journey from a slab of wood to a finished product. More importantly, I experienced the joy and endless possibilities of making things by hand.’’

Colors Begin Spring Offensive

“Pastel Shades of Pale” (oil & cold wax), by Angel Dean, at the Providence Art Club’s “Winter 2025 Members’ Exhibition,’’ through March 27.

“l’ll see you again whenever spring breaks through again.’’

Old-fashioned, sugary romance

No hourly rates though

‘‘The Siesta,’’ by Janet Montecalvo, in the Duxbury Art Association’s “Winter Juried Show,’’ at the Art Complex Museum, Duxbury, Mass., through April 19.

Llewellyn King: A ‘lawless Plutocrat’/autocrat is destroying America’s sense of Mission

World War I poster

“The Fire of Rome’’ (1785), by Hubert Robert. Many have long believed that the great fire, which destroyed much of the empire’s capital, in July 64 A.D., was started by the psychotic Emperor Nero, some of whose traits may remind you of the wanna-be emperor in Washington, D.C.

WEST WARWICK, R.I.

The United States isn’t just a piece of remarkably fertile real estate between two great oceans. It is also a state of mind.

Even when America has done wrong things (think racism) or stupid things (think Prohibition), it has still shone brightly to the world as the citadel of free expression, abundant opportunity, and a place where laws are obeyed.

When I was a teen in a British colony in Africa (now Zimbabwe) long before I imagined I would spend most of my life in America, I met a man who had seen the promised land. He wasn’t a native-born American or even a citizen, but he had lived in “The States.”

I badgered this man with questions about everything, but mostly things derived from books and movies: Could ordinary people really drive Cadillacs? As a British writer later said, were taxis in New York “great yellow projectiles”? Did they really have universities where you could study anything, such as ice-cream manufacturing? Did American policemen actually carry guns?

Our adulation of America was fed by its products. They were everywhere the best. American pickup trucks were the gold standard of light trucks, and American cars — so big — fascinated, although they weren’t ubiquitous like the trucks. Brands such as Frigidaire and General Electric meant reliability, quality and evidence that Americans did things better.

No one thought that the streets in the United States were paved with gold, but they did believe that they were paved with possibility.

There was criticism, like that of the alleged American hold on the price of gold or the fear of nuclear war. The “shining city upon a hill” idea was paramount long before President Ronald Reagan said it.

And it has been so for the world since the end of World War II. For 80 years, the United States has led the world; even when it spread its mistakes, like the Vietnam War, it led.

America was the bulwark of the liberal democracies — a grouping of European nations, Canada, Australia and some of Asia — that shared many values and outlooks. Call it what it is, or was, Western Civilization, based on decency, informed by Christianity, and shaped by tradition and common expectation.

Central to this was America; central with ideas, with wealth, with technological leadership and, above all, with decency. Now, all of this may be in the past.

This structure has been shaken in less than three months of President Trump’s second administration. It is near the breaking point.

This may be the end of days for the Western Alliance, led by America in the ways of democracy and free trade.

Writing in the British monthly magazine Prospect, Andrew Adonis, a peer who sits in the House of Lords as Baron Adonis, states: “Trump doesn’t believe in democracy, just in winning at all costs. He doesn’t believe in an international order based on respect for human rights. He is an authoritarian, lawless plutocrat who admires similar characters at home and abroad.”

Additionally, Adonis says in his article that, unlike the first Trump term, the checks and balances have weakened: “The Republican Party has become a cipher.

The Democrats are shell-shocked and demoralized. The courts, the military and Congress are browbeaten, packed with Trump supporters or otherwise compliant.”

I find it hard to argue with this assessment. Why would Trump persist with a tariff regime that was proven not to work with the Smoot-Hawley Tariff Act of 1930, which helped cause the Great Depression? Why would he rile up Canada by threatening its independence? Why would he reopen, without a good reason, the issue of the control of the Panama Canal?

Why is he destroying the civil service in thought-free ways? Why is he going after the constitutional freedom of the press and the rights enshrined over millennia for lawyers to represent those who need them regardless of politics? Why is he leading us into a recession: the Trump Slump?

Either the president has no coherent plans, or those plans are devious and not to be shared with the people.

I believe that he enjoys power and testing its limits, that he has no knowledge base and so relies on hearsay to formulate policy. In the end, he may be listed along with Roman emperors who ran amok like Nero and Caligula.

The Western Alliance is at stake, and America is giving away its global leadership. When trust is lost, it is gone forever.

On Twitter: @llewellynking2

Llewellyn King is executive producer and host of White House Chronicle, on PBS, and an international energy-sector consultant. He is hased in Rhode Island.

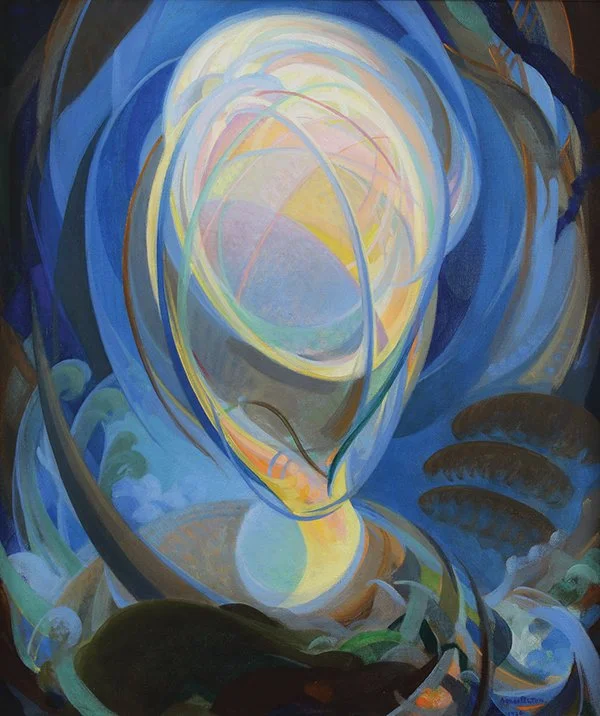

Beats the alternative, for now?

“Being,” c. 1923–26, (oil on canvas), by Agnes Pelton, in the show “Some American Stories,’’ at the Colby College Museum of Art, Waterville, Maine.

The museum says:

“‘Some American Stories’ is a thematic presentation of works from Colby’s collection in the museum’s Lunder Wing that leads visitors on a journey from before the founding of the United States to the present day. Galleries represent a different topic within the broader narrative of American art and history, reflecting a great diversity of experiences’’

Chris Powell: Rent control won’t Build housing; Alleging ‘Meanness’ is not an argument in School-Trans-athletes issue

MANCHESTER, Conn.

Connecticut's cost of living is high, in large part because of housing prices, and nearly everyone says the state needs much more housing, especially ‘‘affordable" housing -- most of which is rental housing. But whether everyone who says that the state needs more housing really believes it is a fair question.

That's because most of the housing legislation proposed in the General Assembly wouldn't increase the supply of housing at all. Most proposals would just scapegoat landlords, though more rental housing requires more landlords. Other proposals would just increase the dependence of renters on government.

State government action that might actually get any “affordable" housing built remains too controversial, even for many Democratic legislators who ordinarily prattle about helping the poor even as many of us argue that Democratic administrations have lately been grinding the poor down with inflation, including high electricity prices, and ineffectual schools.

For example, Democratic legislators want a big increase in state government rent subsidies to tenants, which turn housing into political patronage and take tenants hostage.

Democrats want to forbid landlords from evicting tenants at the end of their leases without ‘‘just cause." End-of-lease evictions undertaken so that landlords can raise rents would be prohibited. This would be rent control, which never got any housing built but only destroyed the private sector's incentive to build rental housing.

Democrats want to forbid landlords from charging more than a month's rent for a security deposit, as if landlords shouldn't have the right to judge how much of a deposit is necessary to protect their property against damage by tenants.

Democrats want to restrict the rent increases that can be charged upon sale of a property -- more rent control.

Democrats want to require even smaller towns to establish “fair rent commissions" -- still more rent control.

Legislation called “Towns Take the Lead" would require towns to set housing construction goals, but there would be no firm enforcement mechanism for achieving them.

Democrats want state government to increase its obstruction of federal immigration-law enforcement and provide more medical-insurance coverage to illegal immigrants, thus incentivizing more illegal immigration, even as state government has never made any provision for housing Connecticut's estimated more than 100,000 immigration-law violators.

The most helpful of the Democratic housing proposals may be the one that would formally authorize homeless people to live, eat and sleep on public land.

Connecticut has many destitute, addicted and mentally ill people, and some of them panhandle and live largely out of sight in the woods or underbrush, but so far the state lacks anything like the sidewalk tenting camps of Los Angeles and Portland, Ore. Maybe that kind of visibility for the destitute and disturbed is necessary to get Connecticut thinking seriously about its housing policy, social disintegration and declining living standards.

The only sure way to get a substantial amount of new housing in Connecticut is for state government to commission it directly and let landlords charge market-rate rents.

Connecticut's cities, with their populations impoverished by state welfare and education policies and their governments surviving mainly on state financial aid, are already wards of the state. They also have large tracts of decrepit industrial and residential property already served by water, sewer, gas and power lines and public transportation -- property that practically begs for redevelopment, especially mixed-use redevelopment, with commerce at street level and residences upstairs, redevelopment that doesn't worsen suburban sprawl.

A state redevelopment authority could be authorized to purchase or condemn such properties and provide them to developers, specifying their development format and completion schedules, while leaving rents to the market so the new properties won't become more government-engineered slums. Cities might resent their loss of control to the state redevelopment authority but then few cities are operated well enough to deserve control of state housing policy any more than suburbs deserve to control it with their exclusive zoning.

Any new middle-class housing will help bring down the cost of all housing nearby, and the cost of living generally. If Connecticut's decentralized political system can't get housing built, state government will have to do it.

‘Mean’ Is No Argument

According to the leader of the Democratic majority in the Connecticut Senate, Norwalk’s Bob Duff, Republican legislators are “mean" for proposing legislation to prevent boys from participating in girls' sports when the boys think of themselves as girls.

“Mean" is pretty tame as Democratic criticism of Republicans goes these days. At least Duff didn’t call the Republicans racist, misogynist or right-wing extremists, as is commonly done by many Democrats without prompting other Democrats to call them “mean."

These days anyone who suggests, for example, that state government shouldn’t be controlled by the government employee unions anymore is bound to be called one of those things, maybe all three. For as Lenin or some other totalitarian is supposed to have observed: If you label something well enough, no argument is needed.

Calling Republicans “mean" for wanting to keep males out of female sports is not an argument. It is a distraction, because there is no argument against keeping males out of female sports, except that doing so may hurt the feelings of the males who think of themselves as female.

But keeping those males out of female sports doesn't deny them the ability to participate in sports, as is sometimes alleged, since they remain free to participate in male sports.

If anyone really needs reminding, the premise of segregating the genders in sports is that on average males are larger, stronger and faster than females, and that only such segregation can assure equal opportunity for females, which the 1972 amendments to Title IX of the Civil Rights Act of 1964 were meant to achieve.

But now that the transgenderism cult has taken over some of the Democratic Party, the party implies that physical differences between the sexes have disappeared and there is no unfairness in requiring females to compete against males, even as males competing as females have famously robbed the latter of deserved victories in Connecticut and throughout the world, sometimes inflicting physical injuries on the females.

That unfairness is what is “mean," though Duff affects not to see it.

If a male can deny biology and merely think himself female and induce government to compel everyone to pretend along with him, what becomes of reality? After all, if the adage is true -- that you’re only as old as you feel -- how can adults be prevented from playing in Little League and lording it over the kids there?

Most people know that the transgenderism cult in sports is nonsense but many are reluctant to say so lest they risk having the cult’s many demagogues call them “mean" or something worse. After all, they may figure that there is only a little injustice here -- to the few females who lose to the males who purport to have transcended their gender and its physical advantages.

Even so, it’s injustice all the same, and resolving the issue in favor of justice might be easy in Connecticut if a team competing against the University of Connecticut’s beloved women’s basketball team recruited a transgender player or two who proceeded to knock the UConn women around in a blowout on television.

The resulting popular indignation might give Connecticut Democrats some political courage.

The Biden administration turned Title IX on its head, the Trump administration is striving to put it back upright, and a few Democratic leaders may be realizing that the country is not inclined to keep pretending along with them that males belong in female sports, bathrooms and prisons, nor to pretend that immigration law enforcement should stop. Indeed, only such Democratic nuttiness could have helped to bring Donald Trump back to the presidency.

California’s Democratic governor, Gavin Newsom, who aspires to his party’s next presidential nomination, appeared to have deduced this the other day when he told an interviewer that male participation in female sports is unfair. This was amazing, since California is where much nuttiness originates.

If Newsom can repudiate the nuttiness, could Senator Duff and other Democrats in Connecticut repudiate it someday as well? Or would that be too “mean"?

Chris Powell has written about Connecticut government and politics for many years (CPowell@cox.net).

‘Individual liberty, individual power’

John Quincy Adams in the 1840’s

“My fellow citizens, your individual liberty is your individual power, and as the power of a community is a mass compounded of powerful individuals, the nation whose people enjoys the most freedom will be, in proportion to its numbers, the most powerful nation on earth.’’

-- John Quincy Adams (1767-1848), of Massachusetts. He served as sixth U.S. president (1825-1829), secretary of state (1817-1825) and congressman (1831-1848).

John Long: Ruminating on deep history amidst current beauty on a late-Winter walk

A Brandt goose

View of Gaspee Point from the north

— Photo by Magicpiano

A couple of weeks ago, in early March, the wind was west at about 10 mph, and it was 28 degrees F. I’d just begun my afternoon walk on Gaspee Point, in Warwick, R.I., and was on the southern bluff facing Greene Island, which is in Occupessatuxet Cove. The sky was a Robin’s egg blue, with not a cloud in sight. Middletown and Bristol’s Colt State Park were well defined in the distance.

Several miles away, as I looked southeast toward the shipping channel near Conimicut Point Lighthouse, I saw the tan, red and white Janice Ann Reinauer making a 90-degree turn in Narragansett Bay, She’s a Pusher-tug, built in Rhode Island, in 2020, powered by two GE (rated at 4720 hp) diesel engines, and with her pilot house rising 53 feet above the bay. She travels from Perth Amboy, N.J., along Long Island Sound to the Mobil oil and gas terminal in East Providence.

Looking east, about 30 yards off the sea wall, I see a small flock of Brandt (Branta bernicla) geese feeding on seaweed at low-low tide. Brandt are about half the size of Canada Geese, and winter on our Narragansett Bay.

However, in the summer they breed on the west coast of Greenland. Mute Swans (Cygnus olor) are swimming further out in the bay, their long, graceful S-shape necks letting them bottom-feed on plants in the shallow water.

I am intrigued by two boulders, called “erratics,’’ deposited by the retreating Laurentide Ice Sheet about 10,000 years ago. Presumably they were once one boulder, which centuries of seasonal ice slowly pried apart, eventually splitting the boulder into two, which are now 50 yards apart on tidal flats.

These erratics’ rounded “heads and shoulders” rise above the bay’s surface at low-low tide. Tidal action over millennia have moved these rocks further and further apart. A half dozen Double-Crested Cormorants (Phalacrocorax auritus) often rest on them while warming themselves by stretching their four-foot black wingspans.

Along a worn footpath above the seawall, a Robin, in a sign of spring, is feeding on berries, maybe Bittersweet, and looking for worms beneath dry leaves and bushes below sandy highlands.

As I saunter along, I occasionally hear a wind chime calling out from a backdrop of nearby houses, but mostly it’s wind whistling through oak and maple branches above me. There’s no aroma of the tidal flats here because of the wind and cold.

Tidal flats stretch out a couple hundred yards into the bay, glistening light-brown in sunlight, and revealing two abandoned 19th Century coal-barge skeletons stranded on what’s left of Greene Island. In the early 1900’s, Greene Island was about five acres, and farmers would bring herds of sheep out to it for grazing on Cord Grass (Sporobolus alterniflorus) during the summer. But on Sept. 21, 1938, a totally unexpected hurricane came with a huge tidal surge and raged across Greene Island, obliterating many summer houses on Gaspee Point. I try to envision the power that it would take to forever obliterate the island’s acres of waist-high Cord Grass. The island is now nearly submerged at high tide.

During the same storm, further south, on the bay’s West Passage, a lighthouse on Whale Rock that had been bolted to its foundation was torn off the rock; the lighthouse keeper’s body was never recovered.

In my sometimes askew imagination, there’s a snapshot of a diorama with a plodding ancient time backdrop, but immediately in front of me, a 270-degree view of the bay’s singular beauty now, with its splendid seasonal cycles. In my mind’s eye, I see reminders of Nature’s power—ice sheets that were nearly a mile thick, big boulders deposited by the sheet, and the hurricanes of 1938 and 1954.

In a month or so, folks like me will look for a pair of ospreys returning from their winter quarters, in Venezuela. We all worry about whether they’ll safely arrive here. They mate for life. The male migrates to Gaspee Point first, to begin rebuilding the couple’s nest on a telephone pole nesting platform. The female will join him a few weeks later.

It won’t be long before we see a dazzling abundance of pink Beach Roses (Rosa rugosa) above Gaspee Point beach’s high-water mark. Hooray for Spring!

John Long is a Warwick-based writer

Taking it in

“Recliner” (bronze), by Joy Brown, in her show “The Art of Joy Brown,’’ at the Hotchkiss School’s Tremaine Gallery, Lakeville, Conn., March 25-April 6.

This retrospective traces Brown’s work, from tiny clay figures to clay-headed puppets, to small statues and wall tiles, to the monumental work found in public spaces.

Richard E. Peltier: Now under threat, Clean-Air rules help health and economy

Smog in Los Angeles

From The Conversation (except for photo above)

Richard E. Peltier is a professor of environmental health sciences at the University of Massachusetts at Amherst.

He receives funding from the U.S. Department of Agriculture and the Rio Grande International Science Center.

The Trump administration announced on March 12 that it is “reconsidering” more than 30 air pollution regulations in a series of moves that could impact air quality across the United States.

“Reconsideration” is a term used to review or modify a government regulation. While Environmental Protection Agency Administrator Lee Zeldin provided few details, the breadth of the regulations being reconsidered affects all Americans. They include rules that set limits for pollutants that can harm human health, such as ozone, particulate matter and volatile organic carbon.

Zeldin wrote that his deregulation moves would “roll back trillions in regulatory costs and hidden ‘taxes’ on U.S. families.” But that’s only part of the story.

What Zeldin didn’t say is that the economic and health benefits from decades of federal clean air regulations have far outweighed their costs. Some estimates suggest every $1 spent meeting clean air rules has returned $10 in health and economic benefits.

In the early 1970s, thick smog blanketed American cities and acid rain stripped forests bare from the Northeast to the Midwest.

Air pollution wasn’t just a nuisance – it was a public health emergency. But in the decades since, the United States has engineered one of the most successful environmental turnarounds in history.

Thanks to stronger air quality regulations, pollution levels have plummeted, preventing hundreds of thousands of deaths annually. And despite early predictions that these regulations would cripple the economy, the opposite has proven true: The U.S. economy more than doubled in size while pollution fell, showing that clean air and economic growth can – and do – go hand in hand.

The numbers are eye-popping.

An Environmental Protection Agency analysis of the first 20 years of the Clean Air Act, from 1970 to 1990, found the economic benefits of the regulations were about 42 times greater than the costs.

The EPA later estimated that the cost of air quality regulations in the U.S. would be about US$65 billion in 2020, and the benefits, primarily in improved health and increased worker productivity, would be around $2 trillion. Other studies have found similar benefits.

That’s a return of more than 30 to 1, making clean air one of the best investments the country has ever made.

Science-based regulations even the playing field

The turning point came with the passage of the Clean Air Act of 1970, which put in place strict rules on pollutants from industry, vehicles and power plants.

These rules targeted key culprits: lead, ozone, sulfur dioxide, nitrogen oxides and particulate matter – substances that contribute to asthma, heart disease and premature deaths. An example was the removal of lead, which can harm the brain and other organs, from gasoline. That single change resulted in far lower levels of lead in people’s blood, including a 70% drop in U.S. children’s blood-lead levels.

Air Quality regulations lowered the amount of lead being used in gasoline, which also resulted in rapidly declining lead concentrations in the average American between 1976-1980. This shows us how effective regulations can be at reducing public health risks to people. USEPA/Environmental Criteria and Assessment Office (1986)

The results have been extraordinary. Since 1980, emissions of six major air pollutants have dropped by 78%, even as the U.S. economy has more than doubled in size. Cities that were once notorious for their thick, choking smog – such as Los Angeles, Houston and Pittsburgh – now see far cleaner air, while lakes and forests devastated by acid rain in the Northeast have rebounded.

Comparison of growth areas and declining emissions, 1970-2023. EPA

And most importantly, lives have been saved. The Clean Air Act requires the EPA to periodically estimate the costs and benefits of air quality regulations. In the most recent estimate, released in 2011, the EPA projected that air quality improvements would prevent over 230,000 premature deaths in 2020. That means fewer heart attacks, fewer emergency room visits for asthma, and more years of healthy life for millions of Americans.

The economic payoff

Critics of air quality regulations have long argued that the regulations are too expensive for businesses and consumers. But the data tell a very different story.

EPA studies have confirmed that clean air regulations improve air quality over time. Other studies have shown that the health benefits greatly outweigh the costs. That pays off for the economy. Fewer illnesses mean lower health care costs, and healthier workers mean higher productivity and fewer missed workdays.

The EPA estimated that for every $1 spent on meeting air quality regulations, the United States received $9 in benefits. A separate study by the non-partisan National Bureau of Economic Research in 2024 estimated that each $1 spent on air pollution regulation brought the U.S. economy at least $10 in benefits. And when considering the long-term impact on human health and climate stability, the return is even greater.

Hollywood and downtown Los Angeles in 1984: Smog was a common problem in the 1970s and 1980s. Ian Dryden/Los Angeles Times/UCLA Archive/Wikimedia Commons, CC BY

The next chapter in clean air

The air Americans breathe today is cleaner, much healthier and safer than it was just a few decades ago.

Yet, despite this remarkable progress, air pollution remains a challenge in some parts of the country. Some urban neighborhoods remain stubbornly polluted because of vehicle emissions and industrial pollution. While urban pollution has declined, wildfire smoke has become a larger influence on poor air quality across the nation.

That means the EPA still has work to do.

If the agency works with environmental scientists, public health experts and industry, and fosters honest scientific consensus, it can continue to protect public health while supporting economic growth. At the same time, it can ensure that future generations enjoy the same clean air and prosperity that regulations have made possible.

By instead considering retracting clean-air rules, the EPA is calling into question the expertise of countless scientists who have provided their objective advice over decades to set standards designed to protect human lives. In many cases, industries won’t want to go back to past polluting ways, but lifting clean air rules means future investment might not be as protective. And it increases future regulatory uncertainty for industries.

The past offers a clear lesson: Investing in clean air is not just good for public health – it’s good for the economy. With a track record of saving lives and delivering trillion-dollar benefits, air quality regulations remain one of the greatest policy success stories in American history.