‘Behind material culture’

Objects from the installation “The Thief, the Spinner and the Fabulis,” opening April 10 at Mad River Arts, Waitsfield, Vt.

An edited version of the gallery’s statement:

“This exhibition embraces the stories behind material culture and examines the physical object whether as art, gift, ‘symbolic other’ or that which is used by us. The exhibition is a means to understand who we are through what we collect and how ‘physical things’ interact in our lives.

“We’ll curate inanimate objects that our community has loaned to us and will use the composition and symbolism that the still life genre conveys. This installation will be the tool for storytelling about the ‘physical world’ in our community.’’

Chris Powell: Sanctimony city and state milk grim history for patronage

A 1743 copy of the Treaty of Hartford of 1638, which sought to eradicate the Pequot cultural identity by prohibiting the Pequots from returning to their lands, speaking their tribal language, or referring to themselves as Pequots.

The nave of Trinity Church, on the New Haven Green. The Gothic Revival building was constructed in 1814-1816.

MANCHESTER, Conn.

Two more tedious but true tales from the Sanctimony City and the Sanctimony State have unfolded.

In New Haven dozens of people gathered at Trinity Church on the city's green on March 8 to mark the 200th anniversary of the last recorded sale of slaves in the city and Connecticut -- two women who were paraded to the green and purchased by an abolitionist who eventually set them free. Last week's gathering called itself a “service of lamentation and healing."

Meanwhile, at the state Capitol, a legislative committee considered a resolution to condemn the Treaty of Hartford of 1638, which marked the end of the war between the Pequot Indian tribe and its adversaries -- the English, Mohegan and Narragansett tribes. The war killed most of the Pequots and the treaty sought to nullify the few who were left, bestowing them on their adversaries as slaves and prohibiting the tribe's reconstitution.

The events implied that modern society bears some enduring guilt for the abominations of centuries past. Indeed, establishing this guilt seems to have been the political objective. This was mistaken and ironic.

Americans like to believe in their country's exceptionalism, but slavery was and remains a worldwide phenomenon going back millennia and transcending nations and races. The slaves brought to the United States and delivered to white masters had been sold first in west Africa by other Black people. To some extent slavery continues today in Africa, the Middle East, and Asia.

So in the larger context Connecticut's connection to slavery may be more remarkable for the efforts to overthrow it than to sustain it. In any case in no country was there a more devastating war to destroy slavery than what happened in the United States.

But even as New Haveners gathered to “lament" and “heal" from the wrongs of two centuries ago, the city remained the scene of a devastating wrong for which no sanctimonious services of lamentation and healing are ever held. That is, most of the city's children -- members of racial and ethnic minorities, far more numerous than there were ever slaves in the state -- lack parents, live in poverty, and fail in school.

New Haven's schools have the worst chronic absenteeism in the state and many of those schools are in terrible repair. Many of their students, undereducated and demoralized, graduate to a more subtle but far more prevalent form of slavery.

As for the Indian wars of almost four centuries ago, they were full of atrocities, though today it is politically correct to remember only those of the winning side.

The massacre of the Pequots in May 1637 in what is now Groton was the most horrible thing ever to happen in Connecticut. But the Pequots started the war. The tribe's very name meant “destroyers" and they already had made deadly enemies of the Mohegans and Narragansetts long before attacking the English settlement in Wethersfield in April 1637, killing nine unarmed people, including three women, kidnapping two women, and killing the settlement's cattle.

So a month later the English, Mohegans and Narragansetts united in a conclusive slaughter.

While the Treaty of Hartford fairly can be called genocidal, it was itself a response to genocide in an era when genocide was common.

No morality is taught by the sanctimony that evoked these horrors last week. Slavery has had no constituency in Connecticut since those last slaves were sold in 1825. Nor is there any constituency here for genocide, though in modern war civilians are often killed.

But there is a selfish political constituency for mobilizing the horrors of the past.

Sanctimoniously reminding people of slavery can intimidate them out of opposing the claims of racial minorities for more government patronage, though that patronage isn't righting any wrongs.

And sanctimoniously reminding people of the Treaty of Hartford may insulate the absurd patronage enshrined in state law whereby the ultra-distant descendants of the ancient Pequots, the victims of genocide, share a casino duopoly with the ultra-distant descendants of the ancient Mohegans, that genocide's co-perpetrators.

Chris Powell has written about Connecticut government and politics for many years (CPowell@cox.net).

Trump’s assaults make Quebecers feel more Canadian

The Quebec Parliament Building in Quebec City

Tony Webster photo

From The Conversation, except for images above and at bottom.

Yulia Bosworth is a professor of French and Linguistics, at Binghamton University, State University of New York

Yulia Bosworth does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organization that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

As Canadians rally around national unity in response to American tariffs and threats of annexation, kindling a renewed sense of Canadian nationalism, Québec stands in solidarity with the rest of Canada.

A February Angus Reid survey suggests a notable increase in Québecers’ emotional attachment to Canada and in their pride in being a Canadian. Those numbers increased by 15 and 13 percentage points to 45 and 58 per cent, respectively, compared to the findings in a similar poll conducted in December 2024.

A more recent Angus Reid poll has found Québec is the most anti-Donald Trump province in Canada.

Québec has joined the rest of Canada in mounting a strong economic response in the trade war. Premier François Legault has supported boycotting American products and buying local, diversifying exports and reducing barriers to inter-provincial trade.

With 41 percent of Québecers responding that they are less likely to travel to the U.S., the province trails just slightly behind the 48 per cent share of Canadians with the same intentions, according to a Leger poll.

Québec’s distinct identity

In light of these expressions of unity, outgoing Prime Minister Justin Trudeau’s contention that Canadians “are more united than ever” resonates with many in Canada and beyond. His replacement as leader, Mark Carney, told Canadians in his victory speech that Trump is “attacking Canadian workers, families and businesses and we cannot let him succeed …. When we are united, we are Canada strong.”

Québec, however, with its distinct identity within Canada anchored in the French language and a unique culture, faces particular challenges and priorities amid the current crisis.

As a sociolinguist and a discourse analyst with broad expertise in Québec studies, I focus on Québec identity and its distinctiveness within Canada. I am particularly interested in how it is constructed and expressed in public discourse, especially in the media and the political sphere.

Canadian identity had not been a prominent topic of national conversation for some time. In contrast, Québec identity has long been a key topic of public discourse, maintained and fuelled by the province’s media.

As Canadian society re-engages in defining its collective identity, it is especially timely to clarify what defines Québec identity and how the province is grappling with the current crisis.

My work analyzing identity-related public discourse has consistently shown that Québec remains committed to its own vision of identity and belonging. This vision is distinct from the Canadian approach, which is based on multiculturalism and bilingualism.

Interculturalism

In contrast to Canadian multiculturalism, which does not recognize a national or a majority culture, Québec adheres to a model for managing cultural diversity known as interculturalism. Its overarching objective is to reconcile diversity with a national culture rooted in the French language.

Crucially, under interculturalism, the culture of the French-Canadian majority is no longer considered the defining element of Québec identity. Instead, Québecers of all backgrounds are called on to participate in a common civic culture. In this model, the French language serves as the common public language of civic engagement.

When national identity is anchored in a common culture, the link between them becomes vital. When one is threatened, so is the other. Conversely, reinforcing one is likely to strengthen the other.

The Québec state supports and promotes the French language and Québec culture as pillars of Québec identity.

But both English-speaking Canada and French-speaking Canada share the long-standing challenge of resisting Anglo-American cultural domination in order to maintain a distinct cultural identity.

In Québec, where language and culture are central to identity, the risk of annexation into the Anglo-American cultural sphere, or of more tariff-driven cuts to the already underfunded cultural sector, puts Québec identity in serious jeopardy.

Ties between culture and economics

This can help explain why, in addressing the looming economic crisis, Legault has vowed to protect Québec’s language, values and identity.

Economy and culture are deeply interconnected in the province — a coalition of regional arts festivals, for example, has called for an end to directing funds toward U.S.-based companies involved in organizing cultural events in the province.

The Canadian hockey team’s recent win in the 4 Nations Face-off inspired an enthusiastic display of national pride by fans across the country, including in Québec.

The Québec government is in fact working on legislation that would recognize ice hockey as the province’s official sport, another display of the shared passions between Québec and the rest of the country.

The rallying around Canadian identity, sparked by the threat of Trump’s tariffs and annexation, appears to be bringing Québec and the rest of Canada closer together. If so, is this rapprochement stemming from a heightened awareness of shared priorities, or from a growing mutual respect for the distinct ones? The coming weeks and months should provide the answers.

The humble U.S.-Quebec border crossing at Canaan, Vt., before entering Hereford, Quebec. The once-relaxed border has become more tense since Trump regained power.

Performance anxiety

“Backstage” (oil on panel), by Jessica Gandolf, in her show “No Assembly Required,’’ at Moss Galleries, Falmouth, Maine, through April 5.

She says:

“Painting helps organize my thinking, my energy and my perceptions in a way that nothing else does. Seeing art has always made me want to make it. Creating art is a way of making sense of things, of saying something meaningful without words. Sometimes I seem to be calling attention to something at the edge of consciousness or dredging up something long buried. This can happen by making pictures or without using recognizable imagery. Sometimes it feels like magic is involved when uniting the physical presence of paint with the realm of the spirit -- magic born of some combination of anxiety and doggedness, open heartedness and luck.’’

Casco Bay from Falmouth in 191o.

A literary Hill

Window boxes on cobblestoned Acorn Street on Beacon Hill.

— Photo by Ian Howard

(Robert Whitcomb, New England Diary’s editor, is chairman of The Guardian. He edited but did not write this article.)

The imagery of Boston’s charming gas-lit streets and brownstone and brick Federal-style buildings have provided inspiration and residence to some of the most celebrated writers in American literature.

Beacon Hill, in particular, has been an historic home for greats, such as Louisa May Alcott, author of Little Women, and Nathaniel Hawthorne, author of The Scarlet Letter.

The neighborhood has been a source of vivid ink to others, such as Henry David Thoreau, who lived there in his childhood, and Robert Frost, who taught at Harvard University and other schools.

The loosely autobiographical Little Women, by Alcott, is a coming-of-age story about the overlap of childhood and young adulthood, a too swift liminal space where children want to be grown but are hesitant to grow up.

Alcott spent a considerable part of her early life in Boston from 1834 to 1840 before her family settled in Concord. However, she later returned to the city and lived on Beacon Hill in the early 1850s while working as a writer and a social reformer.

Her first published works, The Rival Painters: a Tale of Rome and Flower Fables were both published while she was living at 20 Pinckney Street. Her work as a women’s suffrage activist on Beacon Hill empowered her female characters with agency and self-determination.

Hawthorne, author of The Scarlet Letter, wrote love letters to his future wife from his home at 54 Pinckney Street while working at the Boston Custom House in the 1840s. Before that, he paid for room and board to the poet Thomas Green Fessenden on Hancock Street. He would later say of this period of his life, “I have not lived, but only dreamed about living.”

The heroine of his well-known novel grows beyond her longheld ideals after her Puritan community shuns her into isolation. Through protagonists that develop strong, individualistic approaches to the world,

Hawthorne and Alcott reflected the development of thoughts and views throughout a young adulthood which was spent in large part on Beacon Hill.

Many other authors and poets would have their brushes with Beacon Hill and Boston’s literary influence as well.

Henry James, renowned for the psychological depth of his approach to social complexities, lived at 102 Mount Vernon Street in the 1860s before moving to Europe. His time in Boston exposed him to the evolving nature of American society, a theme that permeates many of his works.

In the 20th Century, Beacon Hill continued to attract literary minds, including Sylvia Plath.

The renowned poet and novelist lived at 9 Willow Street while attending classes at Boston University and working at Massachusetts General Hospital. During her time on Beacon Hill, Plath was mentored by poet Robert Lowell and befriended fellow poet Anne Sexton. The city’s atmosphere and her personal experiences deeply influenced her work, particularly her novel The Bell Jar, which captures the struggles of a young woman navigating mental illness and societal expectations. The history of Beacon Hill is a testament to Boston’s enduring influence as a center of American literature.

These writers, among others, found inspiration in the city’s history, its people and its intellectual climate. Walking through the streets of Beacon Hill today, one can still feel the echoes of these literary greats, their presence lingering in the historic architecture and timeless charm.

Closing in on it

From the Norman B. Leventhal Map & Education Center, at the Boston Public Library:

“This {1785} map was the first American wall map, and among the most important early maps published in the United States. Due to a chronic lack of trained surveyors, engravers and printers in post-Revolutionary War America, very few maps of any kind were published before 1790.

“Using information from several earlier maps and coastal charts published in England, this map of the four New England states -- Massachusetts (including Maine counties), New Hampshire (including Vermont counties), Rhode Island, and Connecticut -- added substantial new information in the northern portions of the map, particularly for the New Hampshire townships and Maine's coastal area.

Creator:

Contributor:

Editor’s note: The big border vagueness at the top of Maine and New Hampshire was cleared up with Secretary of State Daniel Webster’s 1842 negotiations with the United Kingdom.

Childhood’s light and Dark

“Shadows” (archival inkjet print), by Anastasia Sierra, at the Cambridge Art Association.

Martin Abel/Reed Johnson: Is this a Bad sign for Human creativity?

From The Conversation, except for images at the top and bottom

Martin Abel is an assistant professor of economics at Bowdoin College. Reed Johnson is a senior lecturer in Russian, East European and Eurasian Studies at Bowdoin.

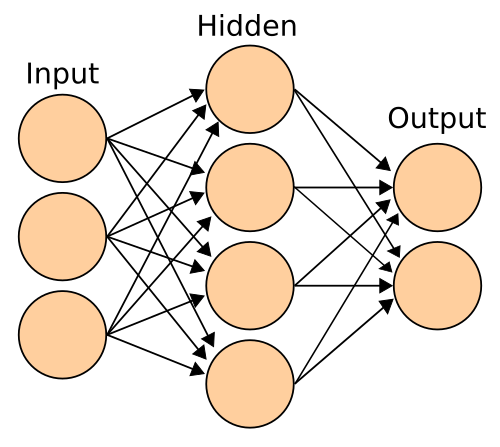

An artificial neural network is an interconnected group of nodes, akin to the vast network of neurons in the human brain.

The authors do not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organization that would benefit from this article, and have disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

People say that they prefer a short story written by a human over one composed by artificial intelligence, yet most still invest the same amount of time and money reading both stories regardless of whether it is labeled as AI-generated.

That was the main finding of a study we conducted recently to test whether this preference of humans over AI in creative works actually translates into consumer behavior. Amid the coming avalanche of AI-generated work, it is a question of real livelihoods for the millions of people worldwide employed in creative industries.

To investigate, we asked OpenAI’s ChatGPT 4 to generate a short story in the style of the critically acclaimed fiction author Jason Brown. We then recruited a nationally representative sample of over 650 people and offered participants $3.50 each to read and assess the AI-generated story. Crucially, only half the participants were told that the story was written by AI, while the other half was misled into believing it was the work of Jason Brown.

After reading the first half of the AI-generated story, participants were asked to rate the quality of the work along various dimensions, such as whether they found it predictable, emotionally engaging, evocative and so on.

We also measured participants’ willingness to pay in order to read to the end of the story in two ways: how much of their study compensation they’d be willing to give up, and how much time they’d agree to spend transcribing some text we gave them.

So, were there differences between the two groups? The short answer: yes. But a closer analysis reveals some startling results.

To begin with, the group that knew the story was AI-generated had a much more negative assessment of the work, rating it more harshly on dimensions like predictability, authenticity and how evocative it is. These results are largely in keeping with a nascent but growing body of research that shows bias against AI in such areas as visual art, music and poetry.

Nonetheless, participants were ready to spend the same amount of money and time to finish reading the story whether or not it was labeled as AI. Participants also did not spend less time on average actually reading the AI-labeled story.

When asked afterward, almost 40 percent of participants said they would have paid less if the same story was written by AI versus a human, highlighting that many are not aware of the discrepancies between their subjective assessments and actual choices.

Why it matters

Our findings challenge past studies showing people favor human-produced works over AI-generated ones. At the very least, this research doesn’t appear to be a reliable indicator of people’s willingness to pay for human-created art.

The potential implications for the future of human-created work are profound, especially in market conditions in which AI-generated work can be orders of magnitude cheaper to produce.

Even though artificial intelligence is still in its infancy, AI-made books are already flooding the market, recently prompting the authors guild to instate its own labeling guidelines.

Our research raises questions whether these labels are effective in stemming the tide.

What’s next

Attitudes toward AI are still forming. Future research could investigate whether there will be a backlash against AI-generated creative works, especially if people witness mass layoffs. After all, similar shifts occurred in the wake of mass industrialization, such as the arts and crafts movement in the late 19th Century, which emerged as a response to the growing automation of labor.

A related question is whether the market will segment, where some consumers will be willing to pay more based on the process of creation, while others may be interested only in the product.

Regardless of how these scenarios play out, our findings indicate that the road ahead for human creative labor might be more uphill than previous research suggested. At the very least, while consumers may hold beliefs about the intrinsic value of human labor, many seem unwilling to put their money where their beliefs are.

View of the Bowdoin campus from Coles Tower.

Photo by Polarbear 11

To get me Out

“Chasing The Horizon” (acrylic, ink, fake fur, cotton on wood panel), by Yeon Ji Yoo, in the show “Wish You Were Here,’’ opening March 22 at the Brattleboro (Vt.) Museum & Art Center.T

Brutal!

Part of the University of Massachusetts at Dartmouth campus, which was designed by Paul Rudolph.

Boston City Hall, designed by Michael McKinnell and Gerhard Kallmann

Photo by andrewjsan - https://www.flickr.com/photos/andrewsan/6776358460/

Adapted from an item in Robert Whitcomb’s “Digital Diary,’’ in GoLocal24.com

The Brutalist, the epic movie about an immigrant architect and Holocaust survivor, has aroused a lot of interest in “Brutalist” architecture, whose heyday was from the 1950’s to the early ‘70s. It’s characterized by minimalist and bulky constructions displaying bare materials, most notably exposed and unpainted concrete or brick, angular shapes and little if any decoration. Brutalism, with its cheap materials and speed of building, was particularly attractive to those rebuilding Europe’s bombed-out cities after World War II.

When I think back to what I walked by in various cities back then, those then-new gray and hulking creations, some with pipes and other utilities exposed, often come to mind.

Some of these buildings are, or were when they went up, quite exciting, even Boston’s famous or infamous city hall, which went up in 1968, or the campus of the University of Massachusetts at Dartmouth, built in the mid and late ’60s. But more people consider them dystopian than beautiful. They also tend to leak! And a big problem is that concrete walls don’t age well, especially in damp climates such as New England’s. The concrete tends to collect dirt and stain, and its heaviness weighs on our spirits. Of course, granite, marble and other rock walls look heavy, too, but they can be very beautiful, if expensive.

Most people want some texture, charm and warmth in their built environments – say with weathered brick and wood, seasoned with sometimes quirky decoration, some of it criminally cute. They want to be comforted by the built environments they live amongst. That isn’t to say that they can’t see the beauty in such gorgeous glassy, glittery Modernist (but not Brutalist) creations as the John Hancock Tower in Boston or New York’s Seagram Building and Lever House. (I loved to look at them by day or night when I worked in New York in the ‘70’s.)

In any event, Brutalism has had its run, which all in all is a good thing, though some of the “Post-Modernist’’ architecture that has succeeded it since the 80’s is hackneyed, with pastiches of various styles, newish and ancient, looking glued together.

A stripped-down Post-Modernist building at Dartmouth College, in Hanover, N.H. Completed in 2002, it was designed by Venturi, Scott Brown and Associates, Inc. in association with Shepley Bulfinch Richardson and Abbott. Its style references Georgian architecture, the dominant look of buildings on the campus.

AKA St. Patrick’s Day

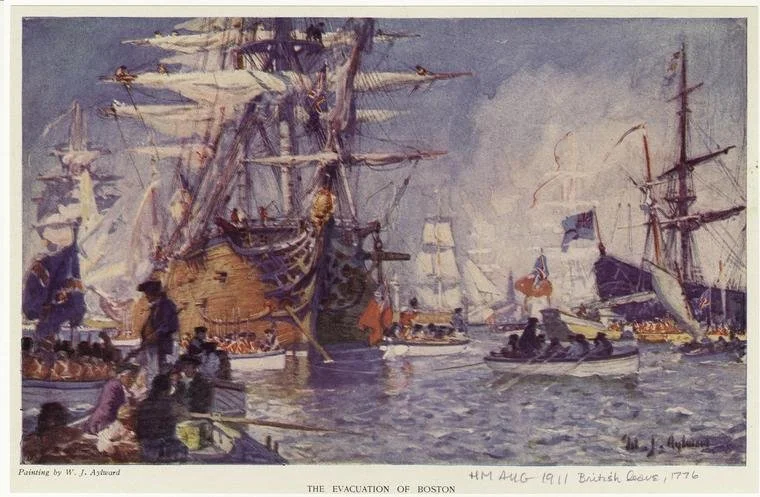

The evacuation of Boston by the British, on March 17, 1776. That, and not St. Patrick, is why it’s an official holiday in Suffolk County, Mass.

— Painting by William James Aylward

Is it your Servant or Master?

P.T. Barnum

“Money is in some respects like fire; it is a very excellent servant but a terrible master. When you have it mastering you; when interest is constantly piling up against you, it will keep you down in the worst kind of slavery. But let money work for you, and you have the most devoted servant in the world.’’

— P.T. Barnum, (1810-1891), of Bridgeport, Conn. (where he served as mayor), American showman and politician famous for promoting celebrated hoaxes and founding with James Anthony Bailey what became known as the Ringling Bros. and Barnum & Bailey Circus. He was also an author, publisher and philanthropist, but said of himself: “I am a showman by profession ... and all the gilding shall make nothing else of me."

‘between hand-made and mass-Produced’

“Snulpture #4” (welded steel, fabric, audio and kinetic electronics), by Andrew Zimmerman, in his show “Snulpture,’’ at Boston Sculptors Gallery, opening April 3.

He says:

“In my work I am interested exploring the intersection between painting and sculpture, art and design, the hand-made and the mass-produced. I am excited by the tension that arises from situating my work in between these categories. I would like my paintings to create moments of unexpected discovery within a language of reconstructable forms.

“I fondly remember working with my dad in his wood shop as a young child. Cutting the parts and assembling the pieces into a bench or a table revealed to me a magical journey from a slab of wood to a finished product. More importantly, I experienced the joy and endless possibilities of making things by hand.’’

Colors Begin Spring Offensive

“Pastel Shades of Pale” (oil & cold wax), by Angel Dean, at the Providence Art Club’s “Winter 2025 Members’ Exhibition,’’ through March 27.

“l’ll see you again whenever spring breaks through again.’’

Old-fashioned, sugary romance

No hourly rates though

‘‘The Siesta,’’ by Janet Montecalvo, in the Duxbury Art Association’s “Winter Juried Show,’’ at the Art Complex Museum, Duxbury, Mass., through April 19.

Llewellyn King: A ‘lawless Plutocrat’/autocrat is destroying America’s sense of Mission

World War I poster

“The Fire of Rome’’ (1785), by Hubert Robert. Many have long believed that the great fire, which destroyed much of the empire’s capital, in July 64 A.D., was started by the psychotic Emperor Nero, some of whose traits may remind you of the wanna-be emperor in Washington, D.C.

WEST WARWICK, R.I.

The United States isn’t just a piece of remarkably fertile real estate between two great oceans. It is also a state of mind.

Even when America has done wrong things (think racism) or stupid things (think Prohibition), it has still shone brightly to the world as the citadel of free expression, abundant opportunity, and a place where laws are obeyed.

When I was a teen in a British colony in Africa (now Zimbabwe) long before I imagined I would spend most of my life in America, I met a man who had seen the promised land. He wasn’t a native-born American or even a citizen, but he had lived in “The States.”

I badgered this man with questions about everything, but mostly things derived from books and movies: Could ordinary people really drive Cadillacs? As a British writer later said, were taxis in New York “great yellow projectiles”? Did they really have universities where you could study anything, such as ice-cream manufacturing? Did American policemen actually carry guns?

Our adulation of America was fed by its products. They were everywhere the best. American pickup trucks were the gold standard of light trucks, and American cars — so big — fascinated, although they weren’t ubiquitous like the trucks. Brands such as Frigidaire and General Electric meant reliability, quality and evidence that Americans did things better.

No one thought that the streets in the United States were paved with gold, but they did believe that they were paved with possibility.

There was criticism, like that of the alleged American hold on the price of gold or the fear of nuclear war. The “shining city upon a hill” idea was paramount long before President Ronald Reagan said it.

And it has been so for the world since the end of World War II. For 80 years, the United States has led the world; even when it spread its mistakes, like the Vietnam War, it led.

America was the bulwark of the liberal democracies — a grouping of European nations, Canada, Australia and some of Asia — that shared many values and outlooks. Call it what it is, or was, Western Civilization, based on decency, informed by Christianity, and shaped by tradition and common expectation.

Central to this was America; central with ideas, with wealth, with technological leadership and, above all, with decency. Now, all of this may be in the past.

This structure has been shaken in less than three months of President Trump’s second administration. It is near the breaking point.

This may be the end of days for the Western Alliance, led by America in the ways of democracy and free trade.

Writing in the British monthly magazine Prospect, Andrew Adonis, a peer who sits in the House of Lords as Baron Adonis, states: “Trump doesn’t believe in democracy, just in winning at all costs. He doesn’t believe in an international order based on respect for human rights. He is an authoritarian, lawless plutocrat who admires similar characters at home and abroad.”

Additionally, Adonis says in his article that, unlike the first Trump term, the checks and balances have weakened: “The Republican Party has become a cipher.

The Democrats are shell-shocked and demoralized. The courts, the military and Congress are browbeaten, packed with Trump supporters or otherwise compliant.”

I find it hard to argue with this assessment. Why would Trump persist with a tariff regime that was proven not to work with the Smoot-Hawley Tariff Act of 1930, which helped cause the Great Depression? Why would he rile up Canada by threatening its independence? Why would he reopen, without a good reason, the issue of the control of the Panama Canal?

Why is he destroying the civil service in thought-free ways? Why is he going after the constitutional freedom of the press and the rights enshrined over millennia for lawyers to represent those who need them regardless of politics? Why is he leading us into a recession: the Trump Slump?

Either the president has no coherent plans, or those plans are devious and not to be shared with the people.

I believe that he enjoys power and testing its limits, that he has no knowledge base and so relies on hearsay to formulate policy. In the end, he may be listed along with Roman emperors who ran amok like Nero and Caligula.

The Western Alliance is at stake, and America is giving away its global leadership. When trust is lost, it is gone forever.

On Twitter: @llewellynking2

Llewellyn King is executive producer and host of White House Chronicle, on PBS, and an international energy-sector consultant. He is hased in Rhode Island.

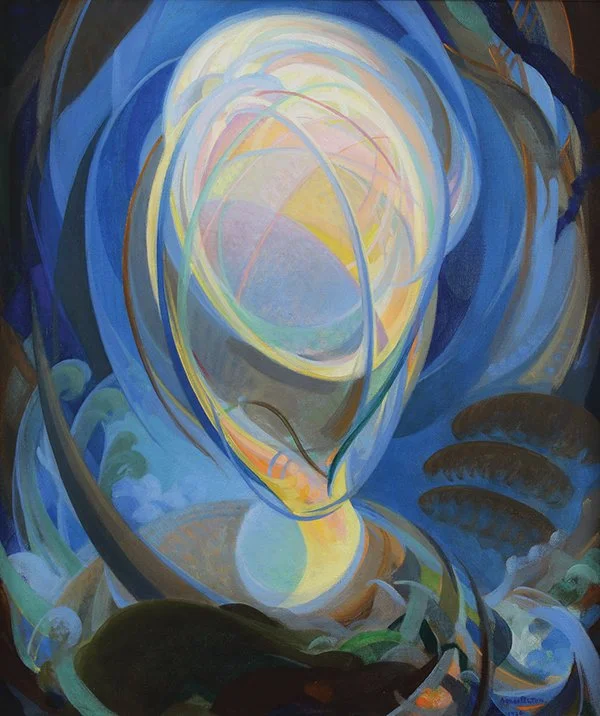

Beats the alternative, for now?

“Being,” c. 1923–26, (oil on canvas), by Agnes Pelton, in the show “Some American Stories,’’ at the Colby College Museum of Art, Waterville, Maine.

The museum says:

“‘Some American Stories’ is a thematic presentation of works from Colby’s collection in the museum’s Lunder Wing that leads visitors on a journey from before the founding of the United States to the present day. Galleries represent a different topic within the broader narrative of American art and history, reflecting a great diversity of experiences’’

Chris Powell: Rent control won’t Build housing; Alleging ‘Meanness’ is not an argument in School-Trans-athletes issue

MANCHESTER, Conn.

Connecticut's cost of living is high, in large part because of housing prices, and nearly everyone says the state needs much more housing, especially ‘‘affordable" housing -- most of which is rental housing. But whether everyone who says that the state needs more housing really believes it is a fair question.

That's because most of the housing legislation proposed in the General Assembly wouldn't increase the supply of housing at all. Most proposals would just scapegoat landlords, though more rental housing requires more landlords. Other proposals would just increase the dependence of renters on government.

State government action that might actually get any “affordable" housing built remains too controversial, even for many Democratic legislators who ordinarily prattle about helping the poor even as many of us argue that Democratic administrations have lately been grinding the poor down with inflation, including high electricity prices, and ineffectual schools.

For example, Democratic legislators want a big increase in state government rent subsidies to tenants, which turn housing into political patronage and take tenants hostage.

Democrats want to forbid landlords from evicting tenants at the end of their leases without ‘‘just cause." End-of-lease evictions undertaken so that landlords can raise rents would be prohibited. This would be rent control, which never got any housing built but only destroyed the private sector's incentive to build rental housing.

Democrats want to forbid landlords from charging more than a month's rent for a security deposit, as if landlords shouldn't have the right to judge how much of a deposit is necessary to protect their property against damage by tenants.

Democrats want to restrict the rent increases that can be charged upon sale of a property -- more rent control.

Democrats want to require even smaller towns to establish “fair rent commissions" -- still more rent control.

Legislation called “Towns Take the Lead" would require towns to set housing construction goals, but there would be no firm enforcement mechanism for achieving them.

Democrats want state government to increase its obstruction of federal immigration-law enforcement and provide more medical-insurance coverage to illegal immigrants, thus incentivizing more illegal immigration, even as state government has never made any provision for housing Connecticut's estimated more than 100,000 immigration-law violators.

The most helpful of the Democratic housing proposals may be the one that would formally authorize homeless people to live, eat and sleep on public land.

Connecticut has many destitute, addicted and mentally ill people, and some of them panhandle and live largely out of sight in the woods or underbrush, but so far the state lacks anything like the sidewalk tenting camps of Los Angeles and Portland, Ore. Maybe that kind of visibility for the destitute and disturbed is necessary to get Connecticut thinking seriously about its housing policy, social disintegration and declining living standards.

The only sure way to get a substantial amount of new housing in Connecticut is for state government to commission it directly and let landlords charge market-rate rents.

Connecticut's cities, with their populations impoverished by state welfare and education policies and their governments surviving mainly on state financial aid, are already wards of the state. They also have large tracts of decrepit industrial and residential property already served by water, sewer, gas and power lines and public transportation -- property that practically begs for redevelopment, especially mixed-use redevelopment, with commerce at street level and residences upstairs, redevelopment that doesn't worsen suburban sprawl.

A state redevelopment authority could be authorized to purchase or condemn such properties and provide them to developers, specifying their development format and completion schedules, while leaving rents to the market so the new properties won't become more government-engineered slums. Cities might resent their loss of control to the state redevelopment authority but then few cities are operated well enough to deserve control of state housing policy any more than suburbs deserve to control it with their exclusive zoning.

Any new middle-class housing will help bring down the cost of all housing nearby, and the cost of living generally. If Connecticut's decentralized political system can't get housing built, state government will have to do it.

‘Mean’ Is No Argument

According to the leader of the Democratic majority in the Connecticut Senate, Norwalk’s Bob Duff, Republican legislators are “mean" for proposing legislation to prevent boys from participating in girls' sports when the boys think of themselves as girls.

“Mean" is pretty tame as Democratic criticism of Republicans goes these days. At least Duff didn’t call the Republicans racist, misogynist or right-wing extremists, as is commonly done by many Democrats without prompting other Democrats to call them “mean."

These days anyone who suggests, for example, that state government shouldn’t be controlled by the government employee unions anymore is bound to be called one of those things, maybe all three. For as Lenin or some other totalitarian is supposed to have observed: If you label something well enough, no argument is needed.

Calling Republicans “mean" for wanting to keep males out of female sports is not an argument. It is a distraction, because there is no argument against keeping males out of female sports, except that doing so may hurt the feelings of the males who think of themselves as female.

But keeping those males out of female sports doesn't deny them the ability to participate in sports, as is sometimes alleged, since they remain free to participate in male sports.

If anyone really needs reminding, the premise of segregating the genders in sports is that on average males are larger, stronger and faster than females, and that only such segregation can assure equal opportunity for females, which the 1972 amendments to Title IX of the Civil Rights Act of 1964 were meant to achieve.

But now that the transgenderism cult has taken over some of the Democratic Party, the party implies that physical differences between the sexes have disappeared and there is no unfairness in requiring females to compete against males, even as males competing as females have famously robbed the latter of deserved victories in Connecticut and throughout the world, sometimes inflicting physical injuries on the females.

That unfairness is what is “mean," though Duff affects not to see it.

If a male can deny biology and merely think himself female and induce government to compel everyone to pretend along with him, what becomes of reality? After all, if the adage is true -- that you’re only as old as you feel -- how can adults be prevented from playing in Little League and lording it over the kids there?

Most people know that the transgenderism cult in sports is nonsense but many are reluctant to say so lest they risk having the cult’s many demagogues call them “mean" or something worse. After all, they may figure that there is only a little injustice here -- to the few females who lose to the males who purport to have transcended their gender and its physical advantages.

Even so, it’s injustice all the same, and resolving the issue in favor of justice might be easy in Connecticut if a team competing against the University of Connecticut’s beloved women’s basketball team recruited a transgender player or two who proceeded to knock the UConn women around in a blowout on television.

The resulting popular indignation might give Connecticut Democrats some political courage.

The Biden administration turned Title IX on its head, the Trump administration is striving to put it back upright, and a few Democratic leaders may be realizing that the country is not inclined to keep pretending along with them that males belong in female sports, bathrooms and prisons, nor to pretend that immigration law enforcement should stop. Indeed, only such Democratic nuttiness could have helped to bring Donald Trump back to the presidency.

California’s Democratic governor, Gavin Newsom, who aspires to his party’s next presidential nomination, appeared to have deduced this the other day when he told an interviewer that male participation in female sports is unfair. This was amazing, since California is where much nuttiness originates.

If Newsom can repudiate the nuttiness, could Senator Duff and other Democrats in Connecticut repudiate it someday as well? Or would that be too “mean"?

Chris Powell has written about Connecticut government and politics for many years (CPowell@cox.net).

‘Individual liberty, individual power’

John Quincy Adams in the 1840’s

“My fellow citizens, your individual liberty is your individual power, and as the power of a community is a mass compounded of powerful individuals, the nation whose people enjoys the most freedom will be, in proportion to its numbers, the most powerful nation on earth.’’

-- John Quincy Adams (1767-1848), of Massachusetts. He served as sixth U.S. president (1825-1829), secretary of state (1817-1825) and congressman (1831-1848).