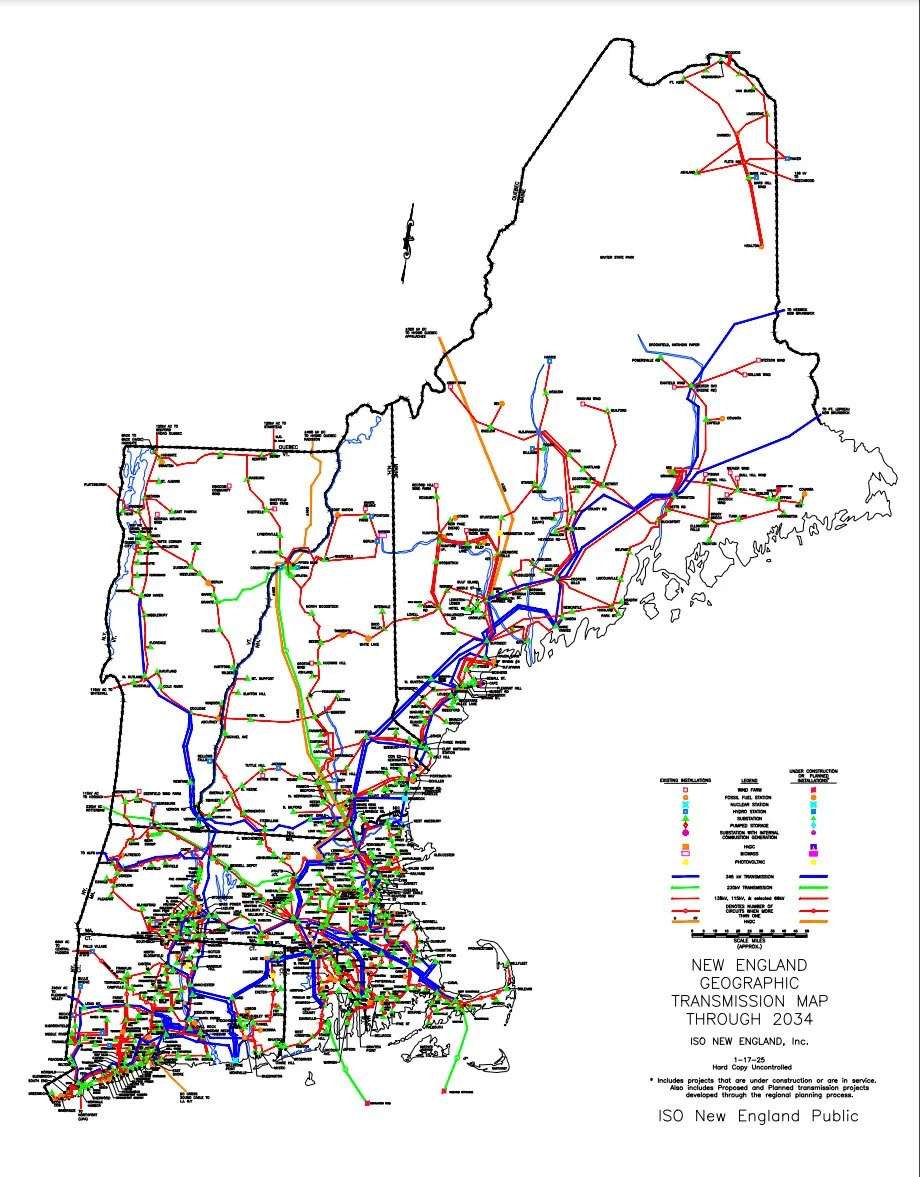

Electric Boat gets over $12.4 billion in contract modifications for Virginia Class submarines

Virginia Class submarine.

Electric Boat facility in Groton, Conn.

BDMillan photo

Edited from a New England Council report

The U.S. Navy has awarded the Electric Boat division of General Dynamics over $12.4 billion in contract modifications to build two new Virginia-class submarines. Authorized first in the fiscal 2024 defense budget, the award will not only help Electric Boat design, build and repair the nuclear submarines, but it will also be invested in improvements to the Groton, Conn., shipyard to help boost workforce-support and productivity programs.

“Over the past two years, we successfully worked with the Navy, Congress and the administration to secure funds that enable us to increase wages for the nuclear-powered vessel workforce and allow for significant additional investments in capacity, shipyard processes and systems,” said Mark Rayha, president of General Dynamics Electric Boat. “This contract modification validates the unique and important role submarines and submarine shipbuilders play in our national defense.”

Congressman Joe Courtney (D.-Conn.), ranking member of the House Seapower and Projection Forces Subcommittee, called the award a “welcomed development for our effort to hire and retain a highly-skilled shipyard workforce in southern New England.”

Natural art

“Morris Island Art, Chatham, Cape Cod,’’ by Bobby Baker

— Copyright Bobby Baker Fine Art

“At the beach, the time you enjoy wasting is not wasted.”

— T. S. Eliot (1888-1965)

Foreign and issue flags shouldn’t be displayed at government buildings

Palestine flag

Adapted from Robert Whitcomb’s “Digital Diary,’’ in GoLocal24.com

Palestinian flags have recently been displayed in the Providence City Council chamber and over City Hall. The display of flags of foreign jurisdictions at such public buildings is utterly inappropriate. The only flags that belong in such a setting are the U.S., state and Providence flags. The councilors have enough important work to do for their constituents without getting into international controversies.

The Palestinian flag was particularly inappropriate given that the U.S. doesn’t recognize the existence of a country called Palestine. Flying the flag was a political statement, apparently led by City Council President Rachel Miller. Domestic-issue flags, such as LGBTQ Pride flags, are also inappropriate at government buildings.

In the next hurricane

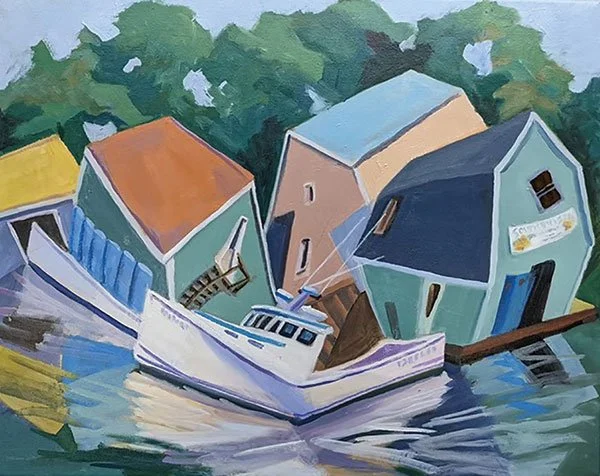

“Rocking the Boat” (oil on canvas), by Sarah L. Fisher, in the show “Flights of Fancy,’’ at Maine Art Gallery, Wiscasset, Maine.

- Courtesy of Maine Farmland Trust

Exploring ‘mythologies, societies, states of being’

“Weightless” (stoneware, encaustic, pigment), by Massachusetts-and-Maine-based artist (including interior design) Sarah Springer.

Her artist’s statement includes this:

“In the metamorphic alchemy of clay, encaustic wax, and found materials, my work explores a diverse array of human mythologies, societies, and states of being.’’

When the Feds built nice housing for working-class people

Plans and elevations of typical U.S. Housing Corporation housing.

From The Conversation, except for image above

Eran Ben-Joseph is a professor of landscape architecture and urban planning at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT), in Cambridge, Mass.

He does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organization that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond his academic appointment.

In 1918, as World War I intensified overseas, the U.S. government embarked on a radical experiment: It quietly became the nation’s largest housing developer, designing and constructing more than 80 new communities across 26 states in just two years.

These weren’t hastily erected barracks or rows of identical homes. They were thoughtfully designed neighborhoods, complete with parks, schools, shops and sewer systems.

In just two years, this federal initiative provided housing for almost 100,000 people.

Few Americans are aware that such an ambitious and comprehensive public housing effort ever took place. Many of the homes are still standing today.

But as an urban planning scholar, I believe that this brief historic moment – spearheaded by a shuttered agency called the United States Housing Corporation – offers a revealing lesson on what government-led planning can achieve during a time of national need.

Government mobilization

When the U.S. declared war against Germany in April 1917, federal authorities immediately realized that ship, vehicle and arms manufacturing would be at the heart of the war effort. To meet demand, there needed to be sufficient worker housing near shipyards, munitions plants and steel factories.

So on May 16, 1918, Congress authorized President Woodrow Wilson to provide housing and infrastructure for industrial workers vital to national defense. By July, it had appropriated $100 million – about $2.3 billion today – for the effort, with Secretary of Labor William B. Wilson tasked with overseeing it via the U.S. Housing Corporation.

Over the course of two years, the agency designed and planned over 80 housing projects. Some developments were small, consisting of a few dozen dwellings. Others approached the size of entire new towns.

For example, Cradock, near Norfolk, Va., was planned on a 310-acre site, with more than 800 detached homes developed on just 100 of those acres. In Dayton, Ohio, the agency created a 107-acre community that included 175 detached homes and a mix of over 600 semidetached homes and row houses, along with schools, shops, a community center and a park.

Designing ideal communities

Notably, the Housing Corporation was not simply committed to offering shelter.

Its architects, planners and engineers aimed to create communities that were not only functional but also livable and beautiful. They drew heavily from Britain’s late-19th century Garden City movement, a planning philosophy that emphasized low-density housing, the integration of open spaces and a balance between built and natural environments.

Importantly, instead of simply creating complexes of apartment units, akin to the public housing projects that most Americans associate with government-funded housing, the agency focused on the construction of single-family and small multifamily residential buildings that workers and their families could eventually own.

This approach reflected a belief by the policymakers that property ownership could strengthen community responsibility and social stability. During the war, the federal government rented these homes to workers at regulated rates designed to be fair, while covering maintenance costs. After the war, the government began selling the homes – often to the tenants living in them – through affordable installment plans that provided a practical path to ownership.

A single-family home in Davenport, Iowa, built by the U.S. Housing Corporation. National Archives

Though the scope of the Housing Corporation’s work was national, each planned community took into account regional growth and local architectural styles. Engineers often built streets that adapted to the natural landscape. They spaced houses apart to maximize light, air and privacy, with landscaped yards. No resident lived far from greenery.

In Quincy, Mass., for example, the agency built a 22-acre neighborhood with 236 homes designed mostly in a Colonial Revival style to serve the nearby Fore River Shipyard. The development was laid out to maximize views, green space and access to the waterfront, while maintaining density through compact street and lot design.

At Mare Island, Calif. developers located the housing site on a steep hillside near a naval base. Rather than flatten the land, designers worked with the slope, creating winding roads and terraced lots that preserved views and minimized erosion. The result was a 52-acre community with over 200 homes, many of which were designed in the Craftsman style. There was also a school, stores, parks and community centers.

Infrastructure and innovation

Alongside housing construction, the Housing Corporation invested in critical infrastructure. Engineers installed over 649,000 feet of modern sewer and water systems, ensuring that these new communities set a high standard for sanitation and public health.

Attention to detail extended inside the homes. Architects experimented with efficient interior layouts and space-saving furnishings, including foldaway beds and built-in kitchenettes. Some of these innovations came from private companies that saw the program as a platform to demonstrate new housing technologies.

One company, for example, designed fully furnished studio apartments with furniture that could be rotated or hidden, transforming a space from living room to bedroom to dining room throughout the day.

To manage the large scale of this effort, the agency developed and published a set of planning and design standards − the first of their kind in the United States. These manuals covered everything from block configurations and road widths to lighting fixtures and tree-planting guidelines.

The standards emphasized functionality, aesthetics and long-term livability.

Architects and planners who worked for the Housing Corporation carried these ideas into private practice, academia and housing initiatives. Many of the planning norms still used today, such as street hierarchies, lot setbacks and mixed-use zoning, were first tested in these wartime communities.

And many of the planners involved in experimental New Deal community projects, such as Greenbelt, Md., had worked for or alongside Housing Corporation designers and planners. Their influence is apparent in the layout and design of these communities.

A brief but lasting legacy

With the end of World War I, the political support for federal housing initiatives quickly waned. The Housing Corporation was dissolved by Congress, and many planned projects were never completed. Others were incorporated into existing towns and cities.

Yet, many of the neighborhoods built during this period still exist today, integrated in the fabric of the country’s cities and suburbs. Residents in places such as Aberdeen, Md.; Bremerton, Wash.; Bethlehem, Penn., Watertown, N.Y., and New Orleans may not even realize that many of the homes in their communities originated from a bold federal housing experiment.

These homes on Lawn Avenue in Quincy, Mass., in 2019 were built by the U.S. Housing Corporation. Google Street View

The Housing Corporation’s efforts, though brief, showed that large-scale public housing could be thoughtfully designed, community oriented and quickly executed. For a short time, in response to extraordinary circumstances, the U.S. government succeeded in building more than just houses. It constructed entire communities, demonstrating that government has a major role and can lead in finding appropriate, innovative solutions to complex challenges.

At a moment when the U.S. once again faces a housing crisis, the legacy of the U.S. Housing Corporation serves as a reminder that bold public action can meet urgent needs.

After black fly season?

“Mount Katahdin from the West Branch of the Penobscot” (1870) (oil on canvas), by Virgil Williams, in the current show “Some American Stories,’’ at the Colby College Museum of Art, Waterville, Maine.

— Photo: Peter Siegel, Pillar Digital Imaging LLC.

The show displays art from before the American Revolution to the present day.

Show-biz celebrities take over commencements

Adapted from Robert Whitcomb’s “Digital Diary,’’ in GoLocal 24.com

Many colleges and universities hire show-business and sports figures (and professional sports are part of show biz) much more than, say, scholars to give commencement addresses. I suppose this is to get more publicity to the schools, but it diverts attention from what you’d think would be the institutions’ main mission – the rigorous creation and teaching of knowledge.

My undergraduate alma mater, Dartmouth College, in Hanover, N.H., is a prime example of this obsession with celebrity culture. It has had the likes of Shonda Rimes, Connie Britton, Conan O’Brien, Jake Tapper and sainted tennis legend Roger Federer as recent commencement speakers. This year it will be Sandra Oh, who is, I am told, a famous Canadian-American actress but a mystery to me. But then, our MAGA Master owes his political success to being a “reality TV” star on the absurd but very popular-in-the-Heartland TV show The Apprentice.

One thinks yet again of Neil Postman’s classic book Amusing Ourselves to Death: Public Discourse in the Age of Show Business

The commencement speakers used to be mostly the likes of foreign or U.S. government leaders, diplomats, academics, including celebrated scholars and college presidents, statesmanlike corporate leaders, and philanthropists. Consider that the speaker in 1970, when I got my degree, was the classicist William Arrowsmith, who very briefly mentioned Vietnam. But higher culture doesn’t pack ‘em in.

Familiar scenes in a new light

“Armistad Pier, New London, Connecticut” (silver gelatin print), by William Earle Williams, in his show “Their Kindred Earth,’’ at the Florence Griswold Museum, Old Lyme, Conn., through June 22.

— Photo courtesy of Mr. Williams

The museum says:

“Williams’s poignant images make visible little-known sites significant to enslavement, emancipation, and African Americans’ contributions to Connecticut history and culture. The photos prompt viewers to consider familiar landscapes in a new light and to imagine, perhaps for the first time, what life was like for enslaved people in Connecticut 200 years ago.’’

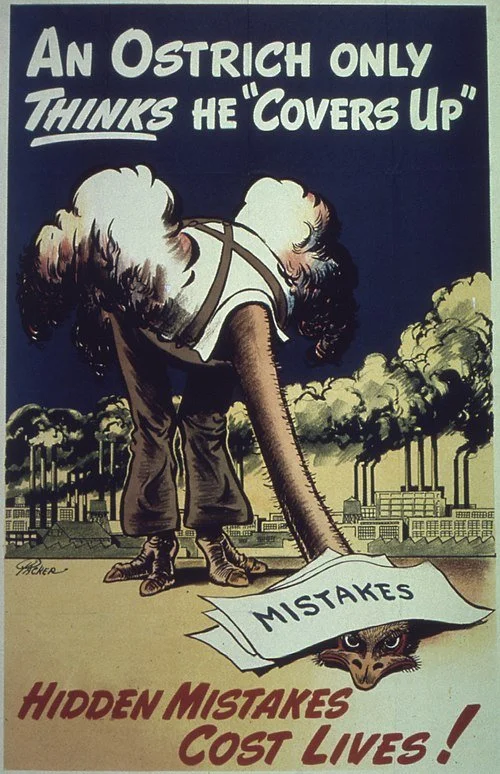

Chris Powell: Hiding police misconduct; inappropriate flags at public buildings

MANCHESTER, Conn.

State government's retreat from accountability for its employees and municipal employees is continuing, as legislation that would conceal accusations of misconduct against police officers is working its way through the General Assembly without any critical reflection by legislators.

The bill, publicized by Connecticut Inside Investigator's Katherine Revello, was approved unanimously by the Senate and would prohibit the release of complaints of misconduct against officers prior to any formal adjudication of the complaints by police management.

Of course that's an invitation to police agencies to conceal all complaints of misconduct and delay formal adjudication of them.

Yes, there can be false or misleading complaints against officers, and maybe disclosure of such complaints will unfairly harm some officer's reputation someday. But the chances of that are small. News organizations aren't likely to publicize such complaints without doing some investigation themselves, and the local news business is withering away.

But police misconduct is always being covered up somewhere, Connecticut has a long record of it, going back to the murder of the Perkins brothers by four state troopers in Norwich in 1969, and chances that government will strive to conceal its mistakes and wrongdoing are always high, just as the chances that the state Board of Mediation and Arbitration will nullify any serious discipline for government employees are always high.

Testifying against the secrecy legislation, former South Windsor Police Chief Matthew Reed, now a lawyer for the state Freedom of Information Commission, noted that the bill would impair the high standards Connecticut purports to want in police work. Reed cited the state law that prohibits municipal police departments from hiring any former officer who resigned or retired while under investigation. If such investigations are kept secret, that law may become useless.

Government employees in Connecticut are always seeking exemption from the scrutiny guaranteed by the state's freedom-of-information law, and imposing secrecy on complaints against police is likely to lead to requests from other groups of government employees for similar exemptions.

Even the state senators from districts with large minority populations who have supported police- accountability legislation in the past seem to have given the complaint-secrecy bill a pass. Maybe they are tired of being criticized as anti-police when they are really pro-accountability. Will there be enough pro-accountability members of the House of Representatives to stop the cover-up enabling act?

“Pride’’ flags like this shouldn’t go up at public buildings.

To help save it from itself, Connecticut could use a few more gadflies like T. Chaz Stevens, a Florida resident who used to live in Shelton, Conn., and who keeps an eye out for government's excessive entanglement with religion.

Stevens is the founder of what he calls the Church of Satanology and Perpetual Soirée, and the other day he scolded the Hartford City Council for having flown a Christian religion flag at City Hall in April. In response Stevens wrote to Mayor Arunan Arulampalam asking that City Hall also fly the flag of his church, thereby complying with the 2022 U.S. Supreme Court decision holding that if government buildings grant requests to fly non-government flags, they have to grant all such requests, lest they violate First Amendment rights.

If Stevens's request is denied, he could sue and well might win.

The Hartford Courant reports that two members of the Hartford City Council, Joshua Michtom and John Gale, both lawyers, saw this problem coming and voted against flying the Christian flag. Other cities in Connecticut recently have made the same mistake by flying a Christian flag on government flagpoles: Bridgeport, New Britain, Torrington and Waterbury.

No matter how the U.S. Constitution is construed, government flagpoles should be restricted to government flags, which represent everyone. Anything else lets the government be propagandized by groups with political influence. That is especially the case with the continuing efforts around the state to fly the “Pride’’ flag on government flagpoles.

The national and state flags already represent freedom of sexual orientation. But the “Pride" flag is construed to represent letting men into women's restrooms, sports, and prisons, politically correct silliness about which there is sharp division of opinion.

Chris Powell has written about Connecticut government and politics for many years (CPowell@cox.net).

17th Century hysteria

From the show “Witch Panic!: Massachusetts Before Salem’’ (witch trials), at the Springfield (Mass.) Museums through Nov. 2

The curator writes:

“Discover a time when people accused of being witches walked among us. Forty years before the infamous trials in Salem, fear gripped the small settlement of Springfield, Massachusetts. Neighbors whispered about Mary and Hugh Parsons as rumors simmered for years, exploding into hysteria that eventually consumed the town. Witch Panic! dives into the daily lives of the Parsons, examining the circumstances that led to their 1651 accusation and arrest for witchcraft.

“Learn about the folklore surrounding witches, like their association with broomsticks, black cats, and cauldrons, or design your own ghoulish familiar, a small creature believed to help witches.’’

A bit of Iowa

Connecticut Valley in Sunderland, Mass., looking south toward Amherst (high buildings at the University of Massachusetts at Amherst.

— Photo by enFrantzDale

“Between Amherst and the Connecticut River lies a little bit of Iowa — some of New England’s more favored farmland. The summer and fall of 1982, Judith bicycled, alone and with Jonathan, down narrow roads between field of asparagus and corn, and she saw the constructed landscape with new eyes, not just looking at houses but searching for ones that might serve as models for her own. She liked the old farmhouses best, their porches and white clapboarded walls.’’

— From House (1982), by Tracy Kidder

Most educated, but might drown

Harvard master's degree gowns

Edited from a Boston Guardian report.

The ZIP code in America with the highest percentage of highly educated people?

If you guessed any of the ZIP codes associated with Harvard or MIT, you guessed wrong.

According to data recently published in The Boston Business Journal, the country’s most educated ZIP code is 02210, which encompasses the Seaport district. 93 percent of its residents have a college degree or higher.

In terms of bright ZIP codes in Massachusetts, the Seaport is followed by:

• Wellesley Hills (02481)

• Waban (02468)

• Newton Highlands (02461)

• Lincoln (01773)

• Dover (02030)

• Brookline (02445)

• Cambridge (02138)

• Lexington (02420)

• Lexington (02421).

Other Boston ZIP codes on the list are 02215 (Fenway/Kenmore Square) at number 11, 02114 (Beacon Hill/West End) at 18 and 02113 (North End) at 24.

If you live anywhere else, study harder.

Speaking to fantasies about under-represented cultures

“CONERICOT” (paper, cardboard and glue, by Justin Favela, in his show “Do You See What I See?’’ at the New Britain (Conn.) Museum of American Art, through June 22.

The curator explains:

“Brilliant colors, tissue paper, cardboard, and untold stories converge in “Do You See What I See?’’ Nestled throughout the galleries, this exhibition is an exploration of the artist's quest to see himself and the vibrant Latinx community represented within the museum's esteemed collection.

“CONERICOT,’’ Favela’s piñata-inspired mural, draws inspiration from depictions of Latin America from the permanent collection. His immersive installation alludes to the beauty of those landscapes, as well as the fantasies that often color Americans' perceptions of these under-represented cultures.’’

‘For one song more’

Wood Thrush

As I came to the edge of the woods,

Thrush music — hark!

Now if it was dusk outside,

Inside it was dark.

Too dark in the woods for a bird

By sleight of wing

To better its perch for the night,

Though it still could sing.

The last of the light of the sun

That had died in the west

Still lived for one song more

In a thrush's breast.

Far in the pillared dark

Thrush music went —

Almost like a call to come in

To the dark and lament.

But no, I was out for stars;

I would not come in.

I meant not even if asked;

And I hadn't been.

“Come In,’’ by Robert Frost (1874-1963)

Sneaking ‘under the heavy door of learning’

Bronze statue of Dr. Seuss and his character “The Cat in the Hat” outside the Geisel Library at the University of California at San Diego.

Ad done by the author and artist who became the famous Dr. Seuss that ran in the July 14, 2028 issue of The New Yorker.

“Dr Seuss, the creation and the creator, was unlike most adults. He remembered. He retained a sense of the absurd, including the absurdity of the idea that growing up means losing your humor. So, while too many adults spend their time teaching children the seriousness of the situation, he managed to sneak under the heavy door of learning, asking, “Do you like green eggs and ham?”

— Columnist Ellen Goodman (born 1941), on Theodor Seuss Geisel (1904-1991), aka Dr. Seuss. He grew up in Springfield, Mass., and graduated from Dartmouth College.

—

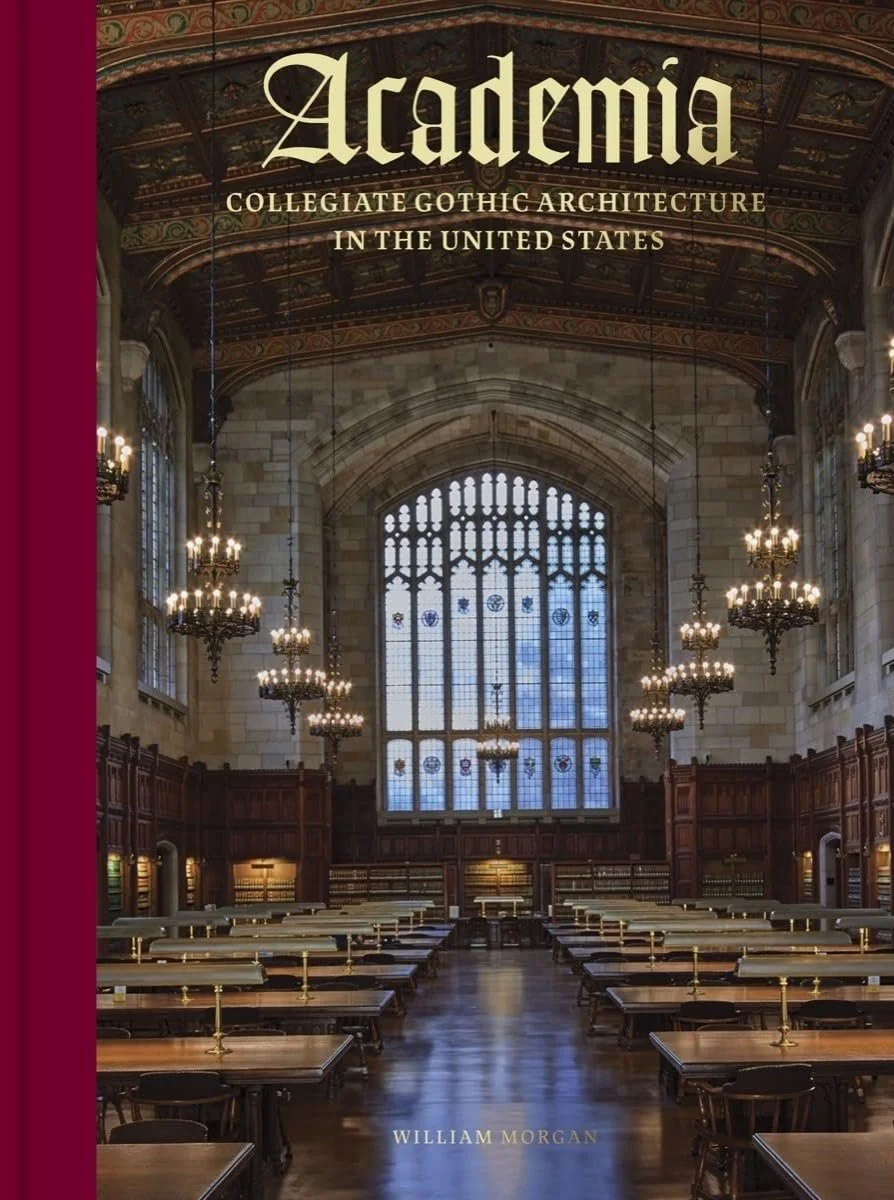

Robert Whitcomb: Morgan’s book says a lot about America

This first appeared in GoLocal24.com

“Americans are the only people in the world known to me whose status anxiety prompts them to advertise their college and university affiliations on the rear window of their automobiles.’’

-- Paul Fussell (1924-2012), American historian

In reading William Morgan’s brilliantly written and gorgeously illustrated new book, Academia – Collegiate Gothic Architecture in the United States, you might recall Winston Churchill’s famous line: “We shape our buildings; thereafter they shape us.’’

I thought of this looking back at an institution I attended, a then-all-boys boarding school in Connecticut called The Taft School, founded by Horace Taft, the brother of President William Howard Taft. Its mostly Collegiate Gothic buildings made some of us students feel we were in a hybrid of a medieval church and a fort. This, I think, encouraged a certain personal rigor and seriousness of purpose, amidst the usual adolescent cynicism and jokiness.

The style originally reflected a certain Anglophilia embraced by some American nouveau riche as they accumulated fortunes in a rapidly expanding economy. Rich donors, and the institutional architects they got hired, wanted to create buildings evoking kind of elite, aristocratic culture at certain old Protestant colleges and universities and private boarding schools. (Many of the latter were modeled on English boarding schools catering to the aristocracy.) There was often a lot of snobbery involved. But the style spread to other institutions, too, including businesses and government offices, around the country.

Some of this included fantastical (to the point of silliness) ornamentation and instant aging of stonework to suggest the wear of centuries on what were brand-new buildings, perhaps most flamboyantly at Yale. Get out those gargoyles!

This book is about much more than architecture. It’s also about personalities, many of them colorful, class, including social climbing, economics, politics and many other things.

One of the book’s joys is Mr. Morgan’s footnotes, which besides adding to the understanding of the main text, are often very entertaining, sometimes even hilarious.

Robert Whitcomb is editor of New England Diary.

Tragic and frequent

“The Tragedy of War,’’ by Craig Masten. The painting won the New England Watercolor Society’s first prize in the organization’s 2023 New England Regional Exhibition.