David Warsh: What an economist and what a family!

Milton Friedman was recognized with a Nobel Memorial Prize in 1976, but something more important to economics happened that year, and I don’t mean the bicentennial of the American Revolution. The Glasgow Edition of the Works of Adam Smith appeared that year as well, timed to commemorate the two hundredth anniversary of the publication of An Inquiry into the Nature and Causes of The Wealth of Nations.

“Modern economics can be said to have begun with the discovery of the market,” began Sir Alexander Cairncross, Chancellor of the University of Glasgow, in his opening address to the convocation that introduced the new edition.

He continued:

“Although the term “market economy” had yet to be invented, its essential features have debated the strength and limitations of market forces [ever since] and have rejoiced in their superior understanding of these forces. The state, by contrast, needed no such discovery.”

Cultural entrepreneurs in economics, even the most effective among them, such as John Maynard Keynes and Milton Friedman, do their work against the background of hard-earned knowledge of others, standing on the shoulders of giants and all that.

Eight beautiful volumes had rolled off the presses: two containing The Wealth of Nations; another with Smith’s first book, The Theory of Moral Sentiments,; three more volumes of essays, on philosophical subjects (which includes the famous essay on the history of astronomy), jurisprudence, and rhetoric and belles letters; a collection of correspondence and some odds and ends; and, in the eighth, an index to them all.

Each contains introductions by top Smith scholars, with edifying asides tucked in among the footnotes. Two companion volumes accompanied the release, published by Oxford University Press: Essays on Adam Smith, and The Market and the State: Essays in Honor of Adam Smith, by way of penance. Smith had been educated at the University of Glasgow but scorned Oxford, where he spent six post-graduate years, mostly reading. Inexpensive volumes of any or all of the Glasgow edition can be had from the Liberty Fund.

A feast, in other words, for those interested in thinking about such things.

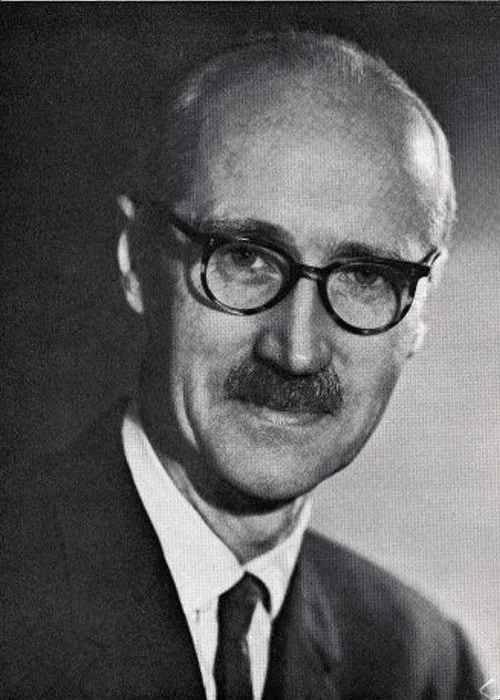

One such was Cairncross, whose Wikipedia entry begins this way:

“Sir Alexander Kirkland Cairncross KCMG FRSE FBA (11 February 1911 – 21 October 1998), known as Sir Alec Cairncross, was a British economist. He was the brother of the spy John Cairncross [worth reading!] and father of journalist Frances Cairncross and public health engineer and epidemiologist Sandy Cairncross.”

More to our point, for twenty-five years Cairncross was chancellor of Glasgow University (1971-1996). It was he who commissioned the Glasgow edition of Smith. He delivered the inaugural address I quoted above.

Before that, however, Cairncross became an economist, as an under graduate at Glasgow (where his namesake had been Chancellor three centuries before, then, beginning in 1932, at Trinity College, Cambridge, under John Maynard Keynes and his increasingly incensed rival, Dennis Robertson. Keynes published his General Theory of Employment, Interest, and Money to great excitement in 1936; Roberson steered Cairncross away from theory and into applied economics. After graduating with honors, he returned to Glasgow as a lecturer and wrote a textbook.

His service in government during World War Two and after was extensive and exemplary: the Ministry of Aircraft Production; Treasury representative at the Potsdam Conference; a stint at The Economist; advisor first to the Board of Trade, then to the Organization for European Economic Cooperation; ten years as Professor of Applied Economics at Glasgow; then, for another decade, various high-ranking positions in the Treasury. The appointment as Glasgow’s Chancellor came in 1971.

If you are interested in post-war Britain, particularly the Sixties, the Royal Academy’s biographical minute on Cairncross makes interesting reading. Quietly told in 1964 about his brother’s treachery as a paid agent of the KGB, he called it “perhaps the greatest shock I ever experienced.”

Cairncross was a Keynesian economist, his biographers say. He was critical of monetarism and dismissed the idea of a “natural” rate of unemployment as absurd. He considered that industrial planning, while necessary in wartime, was no model for peacetime governments. Cairncross “shows that you don’t have to be flamboyant to achieve great influence,” wrote a former boss, “and that you do not have to be malicious to be interesting.”

“By some odd quirk of memory,” his biographers write, in his autobiography, A Life in the Century, Cairncross neglected to mention the Glasgow edition of the works of his fellow Scot that he commissioned, “although he himself had given the opening paper.” Yet that comprehensive record of the circumstances, and, at their center, the founding work – An Inquiry into the Nature and Causes of the Wealth of Nations – from which modern economics emerged may have been his single most durable accomplishment. Cairncross concluded his introductory address to the convocation this way:

“We are more conscious perhaps than Adam Smith of the need to see the market within a social framework and of the ways in which the state can usefully rig the market without destroying its thrust. We are certainly far more willing to concede a larger role for state activities of all kinds, But it is a nice question whether this is because we can lay claim, after two centuries, to a deeper insight in determining the forces determining the wealth of nations or whether more obvious forces have played the largest part: the spread of democratic ideals, increasing affluence, the growth of knowledge, and a centralizing technology that delivers us over to the bureaucrats.”

For an accounting of the lives among the bureaucrats of some distinguished present-day economists, see EP next week.