Llewellyn King: Fusion power is looking more than dreamlike

Commonwealth Fusion Systems (CFS) facility in Devens, Mass.

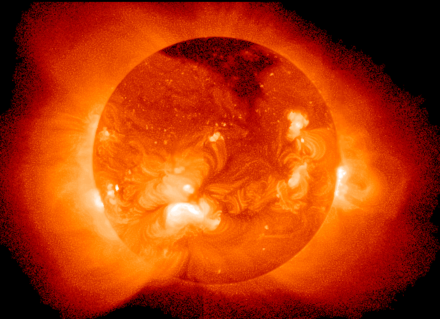

The Sun (here in X-ray) like other stars, is a natural fusion reactor, where stellar nucleosynthesis transforms lighter elements into heavier elements with the release of energy.

WEST WARWICK, R.I.

Fusion power, the Holy Grail of nuclear power for decades, may finally be within our grasp.

If the scientists and engineers at Commonwealth Fusion Systems (CFS), a company with close ties to the Massachusetts Institute of Technology Plasma Science and Fusion Center, are right, fusion is nearly ready for power market entry.

CFS, based in Devens, Mass., says it will be ready to ship its first devices in the early 2030s.

That is astounding news, which has been so long in the making that much of the nuclear industry has failed to grasp it.

I first started writing about fusion power in the 1970s. Having been on hand for many of its false starts, I was one of the doubters.

But after I visited the CFS factory in Devens and saw the precision production of the giant magnets, which are the key to the company’s system, I am on my way to being a believer.

I think that it’s likely that CFS can manufacture a device they can ship to users — utilities or big data centers — in the early 2030s. If so, the news is huge; it is a moment in science history like the first telephone call or the first incandescent light bulb.

Governments, grasping the potential for clean and essentially limitless power without weapons proliferation or radioactive waste, have lavished billions of dollars on fusion energy research worldwide. Intergovernmental effort in recent years has concentrated on the Joint European Torus (JET), which has wrapped up in Britain, and the International Thermonuclear Experimental Reactor (ITER), a mega-project, involving 35 nations, is ongoing in France. Both are firmly in the category of scientific research.

But in the commercial world, there is a sense that fusion power is at hand, and many companies have raised money and are pressing forward. In the front of that pack is CFS.

There are two different technologies chasing the fusion dream: magnetic fusion energy (MFE) and inertial fusion energy (IFE). The former is where plasma at millions of degrees is contained in a magnetic bottle. The trick here isn’t in the plasma, but in the bottle.

A version of MFE, called the tokamak, is the technology expected to produce the first power plant. Worldwide dozens of startups are looking at fusion and in the United States, eight are considered frontline.

The other method, IFE, consists of hitting a small target pellet with an intense beam of energy, which can come from a laser or other device. It is still in the realm of research.

CFS has raised over $2 billion and is seen by many as the frontrunner in the fusion power stakes. It has been supported from its inception in 2018 by the Italian energy giant ENI. Bill Gates’s ubiquitous Breakthrough Energy is an investor. Altogether there are about 60 investors, mostly looking for a huge return as CFS begins to sell its devices.

According to Brandon Sorbom, co-founder and chief scientist at CFS, the big advance has been in the superconducting magnets that create containment bottles for plasma. He told me this had enabled them to design a device many times smaller than had previously been possible.

What makes CFS magnets different and revolutionary is the superconducting wire that is wound to make the magnets.

Think of the tape in a tape recorder, and you have an idea of the flat wire, called HTS, that is wound into each magnet. The HTS tape is first wound into VIPER cable, or NINT pancakes — acronyms for two types of magnet technology, developed by MIT in conjunction with CFS. Then the VIPER cable, or NINT pancakes, are assembled into magnets which make up the tokamak.

This superconducting wire enables a large amount of current to course through the magnet at many times the levels which have been unavailable previously. This means that the device can be smaller — about the size of a large truck.

The next stage is to complete the first full demonstration device at CFS, known as SPARC. Already, it is half-built and should become operational next year.

After that will come the first commercial fusion device, called ARC, which may be deployed in a decade. It will contain, as Sorbom said, “a star in a bottle using magnetic fields in a tokamak design,” and perchance bring abundant zero-carbon energy to users near you.

Llewellyn King is executive producer and host of White House Chronicle, on PBS. His email is llewellynking1@gmail.com and he’s based in Rhode Island.

whchronicle.com