Libby Handros: My times with Lewis Lapham, great editor and essayist and sparkling colleague

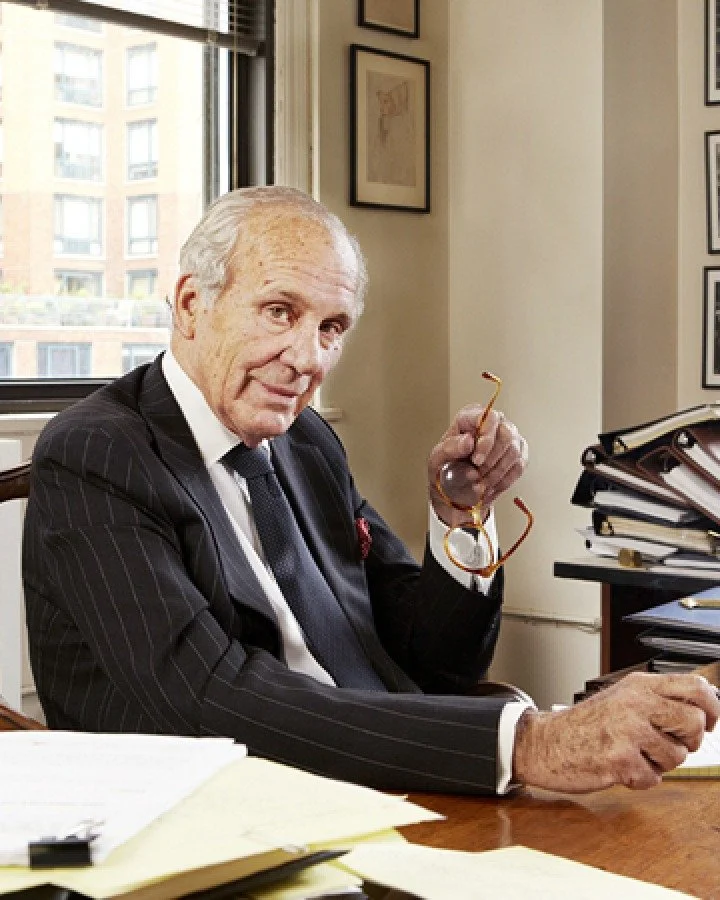

Lewis H. Lapham

— Photo by Joshua Simpson

Lewis H. Lapham wrote and hosted this droll musical film.

I first met Lewis Lapham in the late 80’s at a glittering cocktail party honoring a well-known television critic. It was the type of party that is no longer thrown, and it was also the type of party that Lewis, in his inimitable way, would have had fun critiquing. My boss, Ned Schnurman, introduced us. Ned had great respect for Lewis, who had helped rescue Harper’s Magazine just a few years before. Lewis died on July 23 at 89.

After the cocktail party I ran into Lewis again, having a nightcap at the Hotel Pierre. There, we discussed his idea to do a show that framed the events of the day from the perspective of the past. The two of us collaborated on a proposal for it, but the timing was off, so that particular series was never made.

Sometime later, I was producing a documentary on the “crime of the century” — the Lindbergh-baby kidnapping — and how coverage of the kidnapping and its subsequent trial were the precursors of tabloid television journalism. I needed someone to write the script, and asked Lewis. He had just the right sensibility to connect the contemporary spectacle of the O.J. Simpson trial to the Lindbergh-baby events that had taken place all those years ago in New Jersey. He wrote a beautiful script.

Now we needed an editor. A friend said she knew someone: John Kirby. John had just lost his job, so he was available. The two of us met, little suspecting that a decades-long business partnership would result. I do not recall saying too much. I simply handed John a copy of Lewis’s recently published Lapham’s Rules of Influence. John laughed his way through the book at lunch, and a couple of hours later he was back in my office, full of enthusiasm. “If I had read this book sooner, I might not have just been fired,” he told me.

John’s rough-cut — which made the script into a film — was soon ready for Lewis to review, and the two of them met. They hit it off immediately. Later, after a screening of another cut, Lewis looked at John and said, “Kirby, next time we are going to pick the pictures together.” A year or so after that, the three of us collaborated again, this time on The American Ruling Class, a cutting-edge “dramatic documentary musical” film that follows two newly minted college graduates through the halls of mammon and power.

Lewis found the demands of filmmaking annoyingly time-consuming, but he was always good-natured about it. During the making of ARC, he did take after take outside the Council on Foreign Relations. He sat in the New York Times boardroom talking to Pinch Sulzberger in his own seemingly innocuous way that was anything but. He patiently put up with repeated takes at Elaine’s, the once celebrated Manhattan restaurant and watering hole, sitting with Nickel and Dimed author Barbara Ehrenreich as in a diner. (She was recreating her undercover role as a waitress in the lead-up to a song based on her book.)

There was one shoot that Lewis actually enjoyed: the day we filmed a scene on a golf course. He was happy to keep practicing his swing while we reset the shot or worked with another actor. Eventually I noticed that people were watching him, entranced. One of the onlookers came up to me. “Who is that man practicing his swing?” he asked, pointing. “Lewis Lapham, the editor of Harper’s Magazine,” I responded. The guy’s incredulous reply surprised me: “You mean he isn’t a famous pro?!”

It turned out that, unbeknownst to us, Lewis was a phenomenal golfer. At the Blind Brook Club, the great and near-great of corporate America asked Lewis to join their foursome. After a round of golf, they would settle in for a game of bridge — something else Lewis excelled at.

Years later, Lewis wrote about his personal connection to golf and bridge for Lapham’s Quarterly:

Both my father and my grandfather taught the lesson on the golf course and at the card table. Golf they construed as a trying of the spirit and a searching of the soul. Scornful of what they called “the card-and-pencil point of view,” they looked askance at adding up the mundane trifle of a paltry score.

How one plays the game was more to the point than whether the game is won or lost. Play the shot and accept the consequences, play the shot and know thyself for a bragging scoundrel or a Christian gentleman. So fundamental was my grandfather’s disdain for mere numbers that, at the bridge table, he deemed it ungentlemanly to look at his cards before announcing a bid.

Made for the BBC, The American Ruling Class had a successful festival and theatrical run. It was the most-watched film at the Tribeca Film Festival that year and received special mention in the “New York Loves Documentary” feature category. Lewis, John and I were subsequently invited to attend the prestigious International Documentary Film Festival Amsterdam. Of course we went. Lewis was bemused by his three days there, and John and I were lucky to be with him as he soaked it all in — then wrote about it for Harper’s as only Lewis could, in a piece entitled “Eyes Wide Shut.”

… I was given the chance to look at sequences from a large number of films that one or another of the festival judges thought notable for their cinematography, story lines, and tones of voice — investigative, satirical, didactic, metaphorical, polemical, elegiac. What was striking was the broad range of topic and narrative possibility undreamed of in the philosophy of our own broadcast and cable networks — the civil war in the Sudan (unedited by the missionaries at CNN); cockroach races in Moscow; a pregnant Ukrainian wife sold into the white slave trade and shipped south to Turkey; Honduran peasants hopping Mexican freight trains on their journeys north to the Texas border; street riots in Caracas, happiness in Odessa; Chinese children paid six cents an hour to pick threads from blue jeans on the way to Rodeo Drive; the death in Baghdad of an Iraqi shopkeeper; Brazilian soybeans, genetically modified, being fed to Austrian-engineered chickens. Various in perspective and duration (nine and ninety minutes, with or without voice-over, messages both programmed and spontaneous), the films gave a face, name, age, and address to the grand but often meaningless abstractions that decorate presidential press conferences and drift across the surface of television news — “globalization,” “multinational corporation,” “political unrest,” “environmental degradation,” “widespread poverty,” “incurable disease.”

It is perhaps the best piece ever written about a film festival.

On our last night in Amsterdam, our BBC commissioning editor, Nick Fraser, rounded up a large group of us for dinner. On the way to the restaurant, Lewis announced that he wanted to see “the girls in the window” — aka the city’s infamous red-light district. Then as now, prostitution was legal in Amsterdam, and the girls showed their wares by sitting in picture windows. It was sad. We saw … and left.

After dinner, Lewis wanted to partake in another Dutch tradition: the “coffeeshop,” where pot and hash were also legal. It had been a while since Lewis had smoked pot, he said, but that night he did. What he really enjoyed, however, was his trip to the Rijksmuseum to see the Van Goghs. He loved how the painter captured all walks of society.

In all this time, Lewis had never given up on the original idea that he had pitched to me the first night we’d met: to frame current events from an historical perspective. By now, though, the idea had evolved. He was envisioning a quarterly publication that would focus on a single subject of “current interest and concern — war, poverty, religion, money, medicine, nature, crime — by bringing up to the microphone of the present the advice and counsel of the past.” Thus, Lapham’s Quarterly was born. At an age when others would have been happy to retire and play golf and bridge, Lewis launched a new publication.

The fledgling magazine needed a home, so for several months, Lewis and his small team worked out of our studio in DUMBO, Brooklyn. Lewis sat in our glass box of an editing room with a yellow legal pad, writing and bringing his longtime dream to life. As the circulation for Lapham’s Quarterly grew, Lewis could not have been prouder. He delighted in telling people that, thanks to a grant, his magazine was available in prison libraries.

Much has already been written about how Lewis helped save Harper’s, and the innovations he brought to that magazine. But there was precedent. Some 60 years earlier, another magazine editor had similarly shaken the publishing world: Scofield Thayer, who had taken the reins of The Dial magazine launched by Ralph Waldo Emerson in the 1840s and turned it into the most influential literary publication in 1920s America. Many of the major writers and artists of the day were among the revitalized title’s contributors, such as Sinclair Lewis, Amy Lowell, Archibald MacLeish, Bertrand Russell, Wallace Stevens; Chagall, Matisse, O’Keeffe and Picasso.

Lewis knew his publishing history. The first time he held a copy of The Dial in his hands, he was amazed by its design elements, starting with the table of contents. He realized that he had unconsciously borrowed from Thayer. A mutual friend recognized Thayer’s importance in the world of art and magazine publishing and suggested we make a documentary. We connected everyone, and set out with Lewis as our guide to make a film about Thayer and The Dial; we hope to complete it in the near future, as a memorial to two beloved and innovative editors.

I have not read every single one of Lewis’s Harper’s columns, but I have read many — including his first, which was written in the oil fields of Alaska. Choosing a favorite piece of prose by Lewis Lapham isn’t easy. Everything he wrote offered a new insight, a unique way of viewing the subject du jour. My personal all-time favorite is the prescient, fantastical “A Pig for All Seasons,” which was written during the heyday of the Reagan era and published in the June 1986 Harper’s. As described by Lapham’s Quarterly’s editors, the column “details the rise of the humble pig to the upper echelons of New York society, where it will serve as both companion and bodily insurance policy.”

You can listen to Lewis read the piece on the Quarterly’s site. I must, however, share some of my favorite excerpts here. I think it is Lewis at his inimitable best.

Certainly the manufacture of handmade pigs was consistent with the spirit of an age devoted to the beauty of money. For the kind of people who already own most everything worth owning — for President Reagan’s friends in Beverly Hills and the newly minted plutocracy that glitters in the show windows of the national media — what toy or bauble could match the priceless objet d’art of a surrogate self?

And:

The possession of such a pig obviously would become a status symbol of the first rank, and I expect that the animals sold to the carriage trade would cost at least as much as a Rolls-Royce or beachfront property in Malibu. Anybody wishing to present an affluent countenance to the world would be obliged to buy a pig for every member of the household — for the servants and secretaries as well as for the children. Some people would keep a pig at both their town and country residences, and celebrities as precious as Joan Collins or as nervous as General Alexander Haig might keep herds of twenty to thirty pigs.

Lewis could not stop imagining the pig as a sign of social status and security blanket rolled into one:

As pigs became more familiar as companions to the rich and famous, they might begin to attend charity balls and theater benefits. I can envision collections of well-known people posing with their pigs for photographs in the fashion magazines — Katharine Graham and her pig at Nantucket, William Casey and his pig at Palm Beach, Norman Mailer and his pig pondering a metaphor in the writer’s study.

Celebrities too busy to attend all the occasions to which they’re invited might choose to send their pigs. The substitution could not be construed as an insult, because the pigs — being extraordinarily expensive and well dressed — could be seen as ornamental figures of a stature (and sometimes subtlety of mind) equivalent to that of their patrons. Senators could send their pigs to routine committee meetings, and President Reagan might send one or more of his pigs to state funerals in lieu of Vice President Bush.

People constantly worrying about medical emergencies probably wouldn’t want to leave home without their pigs. Individuals suffering only mild degrees of stress might get in the habit of leading their pigs around on leashes, as if they were poodles or Yorkshire terriers. People displaying advanced symptoms of anxiety might choose to sit for hours on a sofa or a park bench, clutching their pigs as if they were the best of all possible teddy bears, content to look upon the world with the beatific smile of people who know they have been saved.

Lewis was always open to new ideas, which made having drinks with him something to really look forward to. He would frequently arrive pulling a random book or magazine or essay draft out of his Lapham’s Quarterly tote and excitedly talking about it. His personal stories were wonderful, too, whether he was talking about the time he spent as crew on a freighter, or the time he traveled with John D. Rockefeller III to help him promote the idea of birth control, or the time his godfather negotiated with Goering for the return of the Texaco tankers at the start of World War II. A great reporter at heart, Lewis knew a good story when he saw one. Even better, he knew how to tell it.

Lewis was a pleasure to work with. A good friend. An irreplaceable loss.

The tribute to him in Lapham’s Quarterly does him proud. I recommend that you read it.

—Libby Handros, producer, The Press & the Public Project