Rachana Pradhan: And now private equity is getting into the clinical-trial business

Gaston Melingue’s painting shows physician and scientist Edward Jenner vaccinating James Phipps, a boy of eight, against smallpox on May 14 1796. Jenner failed to use a control group in this early clinical trial. The vaccination apparently prevented the boy from getting the dread disease.

“We need to make sure that patients” know enough to provide “adequate, informed consent and ensure “protections about the privacy of the data.”

“We don’t want those kinds of things to be lost in the shuffle in the goals of making money.

— Dr. Aaron Kesselheim, a professor of medicine at Harvard Medical School

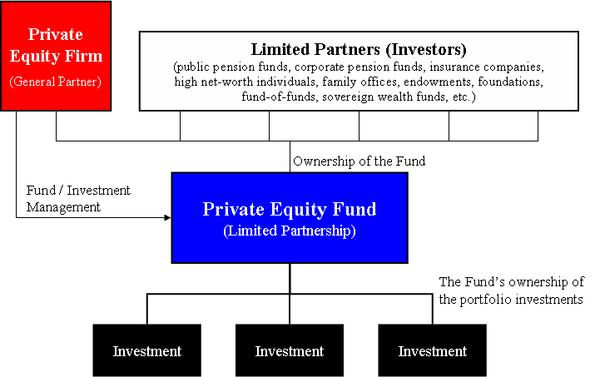

After finding success investing in the more obviously lucrative corners of American medicine — like surgery centers and dermatology practices — private-equity firms have moved aggressively into the industry’s more hidden niches: They are pouring billions into the business of clinical drug trials.

To bring a new drug to market, the FDA requires pharmaceutical firms to perform extensive studies to demonstrate safety and efficacy, which are often expensive and time-consuming to conduct to the agency’s specifications. Getting a drug to market a few months sooner and for less expense than usual can translate into millions in profit for the manufacturer.

That is why a private-equity-backed startup like Headlands Research saw an opportunity in creating a network of clinical sites and wringing greater efficiency out of businesses, to perform this critical scientific work faster. And why Moderna, Pfizer, Biogen and other drug industry bigwigs have been willing to hire it — even though it’s a relatively new player in the field, formed in 2018 by investment giant KKR.

In July 2020, Headlands announced it won coveted contracts to run clinical trials of COVID-19 vaccines, which would include shots for AstraZeneca, Johnson & Johnson, Moderna, and Pfizer.

In marketing its services, Headlands described its mission to “profoundly impact” clinical trials — including boosting participation among racial and ethnic minorities who have long been underrepresented in such research.

“We are excited,” CEO Mark Blumling to bring “COVID-19 studies to the ethnically diverse populations represented at our sites.” Blumling, a drug- industry veteran with venture capital and private equity experience, told KHN that KKR backed him to start the company, which has grown by buying established trial sites and opening new ones.

Finding and enrolling patients is often the limiting and most costly part of trials, said Dr. Marcella Alsan, a public-policy professor at Harvard Kennedy School and an expert on diverse representation in clinical trials, which have a median cost of $19 million for new drugs, according to Johns Hopkins University researchers.

Before COVID hit, Headlands acquired research centers in McAllen, Texas; Houston; metro Atlanta; and Lake Charles, La., saying those locations would help it boost recruitment of diverse patients — an urgent priority during the pandemic in studying vaccines to ward off a disease disproportionately killing Black, Hispanic and Native Americans.

Headlands’s sites also ran, among other things, clinical studies on treatments to combat Type 2 diabetes, postpartum depression, asthma, liver disease, migraines, and endometriosis, according to a review of website archives and the federal Web site ClinicalTrials.gov. But within two years, some of Headlands’ alluring promises would fall flat.

In September, Headlands shuttered locations in Houston — one of the nation’s largest metro areas and home to major medical centers and research universities — and Lake Charles, a move Blumling attributed to problems finding “experienced, highly qualified staff” to carry out the complex and highly specialized work of clinical research. The McAllen site is not taking on new research as Headlands shifts operations to another South Texas location it launched with Pfizer.

What impact did those sites have? Blumling declined to provide specifics on whether enrollment targets for covid vaccine trials, including by race and ethnicity, were met for those locations, citing confidentiality. He noted that for any given trial, data is aggregated across all sites and the drug company sponsoring it is the only entity that has seen the data for each site once the trial is completed.

A fragmented clinical-trials industry has made it a prime target for private equity, which often consolidates markets by merging companies. But Headlands’ trajectory shows the potential risks of trying to combine independent sites and squeeze efficiency out of studies that will affect the health of millions.

Yashaswini Singh, a health economist at Johns Hopkins who has studied private equity acquisitions of physician practices, said consolidation has potential downsides. Singh and her colleagues published research in September analyzing acquisitions in dermatology, gastroenterology, and ophthalmology that found physician practices — a business with parallels to clinical trial companies — charged higher prices after acquisition.

“We’ve seen reduced market competition in a variety of settings to be associated with increases in prices, reduction in access and choice for patients, and so on,” Singh said. “So it’s a delicate balance.”

Dr. Aaron Kesselheim, a professor of medicine at Harvard Medical School, called private equity involvement in trials “concerning.”

“We need to make sure that patients” know enough to provide “adequate, informed consent,” he said, and ensure “protections about the privacy of the data.”

“We don’t want those kinds of things to be lost in the shuffle in the goals of making money,” he said.

Blumling said trial sites Headlands acquired are not charging higher prices than before. He said privacy “is one of our highest concerns. Headlands holds itself to the highest standard.”

Good or bad, clinical trials have become a big, profitable business in the private equity sphere, data shows.

Sohier said “there are few” companies in its long COVID program. That hasn’t stopped Parexel from pitching itself as the ideal partner to shepherd new products, including by doing regulatory work and using remote technology to retain patients in trials. Parexel has worked on nearly 300 covid-related studies in more than 50 countries, spokesperson Danaka Williams said.

Michael Fenne, research and campaign coordinator with the Private Equity Stakeholder Project, which studies private equity investments, said Parexel and other contract research organizations are beefing up their data capacity. The aim? To have better information on patients.

“It kind of ties into access and control of patients,” Fenne said. “Technology makes accessing patients, and then also having more reliable information on them, easier.”

Rachana Pradhan is a Kaiser Health News reporter.

KHN senior correspondent Fred Schulte and Megan Kalata contributed to this report.