Thomas G. Mortenson: How to address America's crisis in higher education

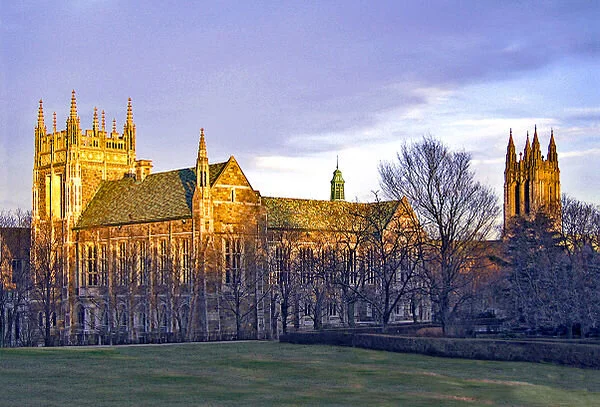

Boston College, which is not in Boston but in Chestnut Hill, Mass., and is, like Dartmouth College, a university

From The New England Journal of Higher Education, a service of The New England Board of Higher Education (nebhe.org)

Something inside me keeps saying: I told you something like this would happen. After 50 years studying opportunity for higher education, I am somewhat comfortable (and very uncomfortable too) saying the issues I have sought to address and warned about underlie the current political chaos. Our failures to address them (and I include higher education centrally in “our”) have boiled over:

1) Income inequality has been surging unchecked for decades. Among the 36 countries that are members of Organization of Economic Cooperation, the U.S. ranks third highest in income inequality. Income is being increasingly concentrated, which means that a growing share of the nation’s prosperity is being concentrated in a shrinking share of the population. With a growing share of the population left out, they have turned to Mr. Trump who had promised to turn the clock back and make America great again. Whatever you and I may think of him, we should remember that 74 million angry people voted for him in the last election.

2) Men’s lives have been falling apart for many decades. We celebrate the success of women and ignore the plight of men. Men have been disengaging from the labor force, from family life, from civic engagement. Our incarceration rates are the highest in the world. And suicide rates among younger males have been exploding. The central problem for men is the shift in employment from goods production to service provision. Men dominated goods production, and women have taken advantage of the growth in service provision employment, particularly through higher education. For every 100 women who earn a bachelor’s degree, 74 men do.

3) Higher education is the engine of division, enriching the rich and leaving everyone else out. From my most recent update, about 13% of children born into the bottom quartile of family income will complete a bachelor’s degree by age 24. About 62% of children born into the top quartile will complete a bachelor’s degree by the same age. This gap has grown substantially since 1970 when I started this data analysis. The bachelor’s degree has become the dividing line between people who are moving forward and people who are moving backward in the economy.

4) As a matter of public policy, I believe that selective college admissions should be replaced with a random draw lottery for admissions. The whole selective college admissions system is outright class warfare. Colleges should remain free to practice selective admissions—but at the price of losing eligibility for Title IV program participation and eligibility for tax-exempt status. These institutions should be treated as the greedy for-profit businesses that they are.

5) Education used to be thought of as an investment in the future. A generation of adults would tax themselves to provide free education for the next generation. The education-loan business reverses this view–let financially needy young people borrow from their own future incomes to be higher educated today. I hate education loans! My proposal to eliminate them would be to increase the Pell Grant maximum award to cost-of-attendance, and then expect states to match the federal effort to fund them. This Pell max should be set to some good quality higher education level, perhaps around $40,000. Colleges that had a higher cost of attendance (COA) would have to fund that from their own resources. My goal is to eliminate the damn loans for higher education, and fully meet demonstrated financial need for students from the bottom half of the family income distribution that are so poorly funded today. Also, I want to force states back into their historic roles funding higher education.

After a half century studying higher-education opportunity, my patience with the current dysfunctional and destructive system was exhausted long ago. Frankly, I am ashamed of the mess my generation has left for the next generation to live with. Again, I say I feel comfortable saying I told you this would happen, but it certainly did not have to happen if we had addressed the issues I tried to raise during my 50 year career.

Thomas G. Mortenson is a higher-education policy analyst, now living in Florida and Minnesota.