David Warsh: Aaron Burr, the Gunpowder Plot and our current scoundrel-in-chief

Vice President Aaron Burr in 1802

SOMERVILLE, Mass.

Donald Trump has begun appearing in the rear-view mirror. I have compared Trump to Aaron Burr, the scoundrel who sought to overturn the 1800 presidential election in the early days of the Republic. Hit this link for an explanation of what he did.

Later, starting in 1804, Burr sought to invent around U.S. elections altogether, hoping to foment a breakaway-nation that he could govern in the Spanish Southwest.

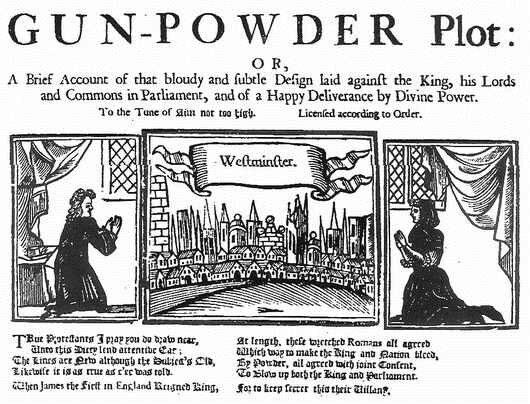

No other episode in American history comes close. But after following news about the Jan. 6 assault on the Capitol, I’m inclined to believe that the history of England offers a more illuminating comparison. I’ve been thinking about Guy Fawkes and the 17th Century Gunpowder Plot.

The background was the Protestant Reformation, which had begun in Germany, in 1517, with Martin Luther. Starting in 1533, King Henry VIII withdrew Britain its allegiance to the Roman Catholic Church. Catholics, especially Jesuit priests, had a hard time of it under Henry’s daughter Queen Elizabeth I. Elizabeth’s Catholic cousin, Mary, Queen of Scots, was executed for treason in 1587.

Elizabeth died childless, in 1603, without having named an heir. Queen Mary’s son, Elizabeth’s nephew, peacefully acceded to the throne as James I of England and James VI of Scotland. But repression of Catholics continued, and in 1605 a group of English Catholics plotted to blow up the House of Lords during the opening of Parliament, on Nov. 5. Betrayed by a letter of seemingly mysterious provenance, one of the plotters, Guy Fawkes, was discovered guarding 36 barrels of gunpowder in the basement the night before, quite enough to demolish the building. The plotters were captured and, one way or another, put to death, including some Catholic clergy linked to the plot.

The world was smaller then. Passions ran deeper. Globalization had only just begun. But it is hard to think of any other episode in Anglo-American history whose rhetorical aim resembled more closely that of the mob that descended on the U.S. Capitol on Jan. 6, having been dispatched on their mission by President Trump.

One group of skirmishers came within seconds of sighting Vice President Pence as he, along with his wife and daughter, was spirited out of the Senate chamber and into a hideaway, according to a Jan. 16 story in The Washington Post. The gunpowder plotters intended to kill King James and install his nine-year-old daughter on the throne as Catholic monarch. The Capitol Hill mob vigorously denounced Pence as a traitor for his failure to overturn the presidential-election results. A mock gallows was installed on the western approach to the Capitol.

Persecution of Catholics continued but was mild relative to the century before for the remainder of the reign of James I – he died in 1625 – but anti-Catholic sentiment persisted in England for two centuries, through a not-unrelated civil war and a very-related “Glorious Revolution.”

No one knows what might be the long-term effects of the assault on the Capitol. My hunch is that it will be remembered as thoroughly repugnant and rejected and condemned until it is forgotten. For a higher-resolution characterological account of the Trump story, see “What TV Can Tell Us about How the Trump Show Ends,” by Joanna Weiss. The Trump presidency resembled an antihero drama, Weiss says, more closely than reality TV, the saga of Tony Soprano her chief case in point.

With this emergency behind, I am returning this weekly to my main concern, economics, meanwhile finishing a book on the last hundred years of its textbook versions. As for my plans to shift to the Substack publishing platform, they are postponed; Economic Principals will move at the end of the year, by which time the book will have begun wending its way its way to the press. Luck be a lady this year!

David Warsh, a veteran columnist and an economic historian, is proprietor of Somerville, Mass.-based economicprincipals.com, where this column originated.