Brutal!

Part of the University of Massachusetts at Dartmouth campus, which was designed by Paul Rudolph.

Boston City Hall, designed by Michael McKinnell and Gerhard Kallmann

Photo by andrewjsan - https://www.flickr.com/photos/andrewsan/6776358460/

Adapted from an item in Robert Whitcomb’s “Digital Diary,’’ in GoLocal24.com

The Brutalist, the epic movie about an immigrant architect and Holocaust survivor, has aroused a lot of interest in “Brutalist” architecture, whose heyday was from the 1950’s to the early ‘70s. It’s characterized by minimalist and bulky constructions displaying bare materials, most notably exposed and unpainted concrete or brick, angular shapes and little if any decoration. Brutalism, with its cheap materials and speed of building, was particularly attractive to those rebuilding Europe’s bombed-out cities after World War II.

When I think back to what I walked by in various cities back then, those then-new gray and hulking creations, some with pipes and other utilities exposed, often come to mind.

Some of these buildings are, or were when they went up, quite exciting, even Boston’s famous or infamous city hall, which went up in 1968, or the campus of the University of Massachusetts at Dartmouth, built in the mid and late ’60s. But more people consider them dystopian than beautiful. They also tend to leak! And a big problem is that concrete walls don’t age well, especially in damp climates such as New England’s. The concrete tends to collect dirt and stain, and its heaviness weighs on our spirits. Of course, granite, marble and other rock walls look heavy, too, but they can be very beautiful, if expensive.

Most people want some texture, charm and warmth in their built environments – say with weathered brick and wood, seasoned with sometimes quirky decoration, some of it criminally cute. They want to be comforted by the built environments they live amongst. That isn’t to say that they can’t see the beauty in such gorgeous glassy, glittery Modernist (but not Brutalist) creations as the John Hancock Tower in Boston or New York’s Seagram Building and Lever House. (I loved to look at them by day or night when I worked in New York in the ‘70’s.)

In any event, Brutalism has had its run, which all in all is a good thing, though some of the “Post-Modernist’’ architecture that has succeeded it since the 80’s is hackneyed, with pastiches of various styles, newish and ancient, looking glued together.

A stripped-down Post-Modernist building at Dartmouth College, in Hanover, N.H. Completed in 2002, it was designed by Venturi, Scott Brown and Associates, Inc. in association with Shepley Bulfinch Richardson and Abbott. Its style references Georgian architecture, the dominant look of buildings on the campus.

William Morgan: Faux Gothic at Providence College

Commentary and photos by WILLIAM MORGAN "I feel to the depths of my being that this emblematic new building is not only a step for Providence College, but for our country," David McCullough declared last October at the dedication of the Ruane Center for the Humanities at the 90-year-old Dominican school in the Rhode Island capital. Despite such noble sentiments from everyone's favorite historian and commencement speaker, the new home of P.C.'s Western Civilization program actually portends a journey into a Disney-fied architectural wilderness.

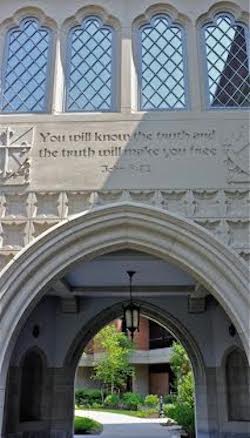

The buttresses and arches of the Ruane Center entrance tower are not structural.

As a style, Collegiate Gothic created some memorable American campus architecture. Ruane Hall, however, falls leagues short of a credible re-creation of either the look or the spirit of Oxford and Cambridge that infused the Princetons, Yales, and Michigans at the turn of 20th Century. That Gilded Age offered architects thoroughly conversant with the past, backed up by skilled craftsmen. What we have today at Providence College is an uninspired piece of real estate wrapped with a thin veneer of brick and a few pointy details. This is the same sort of Potemkin village found in upscale shopping malls and themed suburban restaurants.

Biblical "truth" perhaps, but the Ruane Center's stage-set Gothic is something of a lie. There is no carving whatsoever, just stamped details.

The pasticheurs of this paper-thin storybook castle are the S/L/A/M Collaborative and the Boston firm of Sullivan Buckingham Architects. S/L/A/M is a large, multi-city firm that cranks out instant history for both private colleges and state universities ("Not what kind of building do you need, it's what kind of institution do you want to be"). Sullivan Buckingham, designers of the chapel and an art center at P.C., was founded to provide "traditional" institutional buildings. "Our buildings in various styles," the firm claims, "Classical, Romanesque, and Gothic, are not lifeless copies; they are historically correct." Yet, beyond the battlemented square tower, the classrooms and offices are depressingly yesteryear's high school. The aggressively bland interior is a far cry from the Rugby of Tom Brown's School Days.

The classrooms in the Ruane Humanities Center are more bond-starved public high school than Gothic-inspired halls of learning.

In noting that the Ruane Center stands next to a "Brutalist" library, Sullivan Buckingham naively state that by employing brick and by matching the height of the library they were able to "achieve détente between the warring styles." The very term Brutalism is a bugbear to putative traditionalists, deployed as a weapon with which to excoriate a significant modern movement that they misunderstand. The neighboring Phillips Library–a superb example of Brutalism–is a 1969 work by Sasaki, Dawson and Demay. Long known simply as Sasaki Associates, the Watertown, Massachusetts firm was founded by Hideo Sasaki, one of the great modern landscape architects.

Phillips Library by Sasaki, Dawson and Demay is similar to other bold buildings the firm did at the Universities of Rochester, Louisville and Virginia.

Brutalism is not to everyone's taste, but it deserves more respect than simply being dismissed because of an unfortunate label. This antidote to the slick glass and steel corporate style of the 1950s created some notable rugged concrete architecture, such as the Boston City Hall and the architecture school at Yale.

In seeking historical legitimacy by grasping at a very thin thread back to the Gothic cathedrals, the Dominican college ignores an exceptionally tectonic work. Sasaki's library is a not a decorated box, but a vigorous composition with the constructional logic of true Gothic. One can "read" the elements with which it was constructed, while the brick is honestly expressed here as a curtain wall supported by the reinforced concrete skeleton.

Instead of conjuring up a cheaply constructed faux medievalism, Providence College might recognize that it is the steward of an unsung masterpiece, worthy of contemporaries such Louis Kahn and Paul Rudolph. Thus the irony of the quote by the greatest American Gothicist, Ralph Adams Cram, with which Sullivan Buckingham open their website:

A building must look like what it is, express visibly the energy that informs it, and declare its spiritual and intellectual lineage through its architectural vesture.

This is not a description of the flaccid Ruane Center, but it does fit the library.

Although the interior of the Phillips Library has undergone a questionable decorative overlay of American craftsman detail, one can still experience the evocative raw concrete structural elements, such as these waffle coffers.