Bridge bathos and beauty

Cape Cod Canal Railroad Bridge, in foreground, and Bourne Bridge in December 1935 after soon after they were completed. The Sagamore Bridge is out of sight here.

Adapted from Robert Whitcomb’s “Digital Diary,’’ in GoLocal24.com

Most readers have driven on the two vehicle bridges – the Sagamore and Bourne -- over the spectacular Cape Cod Canal and noticed that the Feds built them both in only two years – 1933-1935 – with equipment and building materials inferior to what we have now. The current bridges have been impressively sturdy, though driving on the two-way spans, with their too-narrow lanes, can be unnerving. Clench your teeth and look straight ahead!

There’s also the Cape Cod Canal Railroad Bridge, also built in 1933-1935, allowing a bit of freight and seasonal passenger service on the Cape.

So the decision has been made to replace the bridges, via a combination of federal and state money. Officials say that construction of the new Sagamore Bridge won’t start until 2027 and building of a new Bourne Bridge until 2029. The hope is to complete the Sagamore Bridge by 2034 and the Bourne Bridge maybe by 2036. The total cost is projected to be $4.5 billion.

(Who of us old folks will be around to see the new bridges, and would we be too decrepit to drive on them? Would the new bridges make things, worse, not better, traffic-wise, by drawing even more people to the Cape?)

It’s very difficult to do big projects in America because of too many sometimes conflicting jurisdictions, too many permitting layers and the sometimes paralyzing fear of litigation. It would be nice if officials used the new bridges as a nation-leading example of how to speed up big projects.

I also thought of how more railroad service to the Cape would help cut down on what is often from May to October’s horrific car traffic going to and from what is a man-made island.

Likewise, Aquidneck Island would be more habitable if a railroad(s) – MBTA and/or Amtrak -- connected it with the outside world and took a lot of vehicles off the road. New bridges would, of course, be needed. The terminus would be at Thames Street in Newport, whence tourists could easily walk to many of the City by the Sea’s famous sights and sites. Alas, that’s more billions of bucks!

‘It would be energizing and uplifting if the new bridges we do put up in such watery places as Rhode Island and Massachusetts were more than just for vehicles. They could be lively attractions, providing dramatic views for pedestrians and bicyclists. There could be plantings on them and maybe even snack bars. They could become like public squares, albeit with anti-suicide fences….

A CapeFLYER train, providing seasonal service, crosses the Cape Cod Canal Railroad Bridge on the Cape Main Line in 2013.

— Photo by Pi.1415926535

Natives, residents and ticks

There are, generally speaking, five sorts of people found on Cape Cod at one time or another: native residents, natives who are not residents, residents who are not natives, summer residents who are natives, and summer residents who are not natives. A sixth classification…is the group known as ‘guests.’ Native residents have had company all their lives, as have summer residents who are natives. These hosts are fairly casual about guests, seeing them as a natural and inevitable part of any year – like ticks.’’

-- Marcia J. Monbleau, in her 2000 book The Inevitable Guest: A Survival Guide to Being Company and Having Company on Cape Cod

The genius of Robert Cray

Robert Cray in concert in 2007

PROVINCETOWN, Mass.

"To say that Robert Cray is a transformational figure for my generation, Gen-X, would not be hyperbole.’’

— "Braintree Jim," the DJ who spins for WOMR , on Cape Cod.

Cray is a singer, songwriter guitarist, known for his unique hybrid of blues and soul. He is a five-time Grammy award winner who has released 19 studio albums, along with an assortment of live recordings and compilations. The Robert Cray Band may not be a household name today, but it has achieved international recognition in the nearly 50 years it, and various iterations, have performed during that time. Cray, who turned 70 earlier this month, regularly visits New England on a relentless, annual touring schedule. He will be spending time here on the Outer Cape during August and into September.

The DJ, who hosts the radio show called Target Ship Radio, further explains his rationale. "I was attending Providence College during the mid-’80’s when Cray's breakthrough album 'Strong Persuader' was released, in late 1986. When I first heard the single 'Smoking Gun' on the radio I simply had to get the album. I was totally taken by it and played it repeatedly. I still have the cassette today."

He recalls that pivotal time for young music fans. "Back then, the ascendant genre was hip hop. Many of my friends were attracted to that whole scene. And by the late 80s, even MTV was showcasing that music. But when I heard Robert Cray, principally a blues guy back then, I went back, not forward. Not only did I buy his back catalog work, which was fantastic, he really helped me discover the blues as a whole other art form.

"Cray, along with Stevie Ray Vaughan, Eric Clapton -- and even Albert Collins and Billy Gibbons -- were part of this exciting blues revival in the 80s and into the early 90s. For me, Cray played an instrumental part in this movement. Cray was affable, the music was accessible. In fact, his whole persona was quite approachable. He was making MTV-style videos that both young men and women found entertaining. And remember, his first national TV debut was on Late Night With David Letterman. By the ‘90s, he was morphing into a soul and R&B performer. He could deliver searing blues numbers for sure, but his music was adapting. That's why I think he's retained this rather remarkable staying power."

Braintree Jim is planning a Robert Cray retrospective on his next show on the Provincetown radio station. "I really think," he reasons, "that Robert Cray should be a bigger name. He's got an unbelievable canon of work that I wish more people heard. So, I want to dedicate three hours of my next show and pay tribute to his music. And he has collaborated with so many people, like Tina Turner, BB King, and Chuck Berry, just to name a few. And he still rips it up on tour. His voice is still the same after all these years and his guitar chops are also still intact."

The radio host further adds that, "I may have eventually discovered the blues without Robert Cray. But It's safe to say that his music really inspired me to appreciate the art form and dig into its rich history. Many of my generation discovered the blues because of Robert Cray. That alone makes him worthy of a three-hour radio show. But the music is so good that it will be tough to boil it down into that time frame. But I'll have fun doing it! That's the great thing about WOMR. I have this incredible level of autonomy in what I can play. That's virtually unheard of in radio today. I will be representing the station at the upcoming concert, too. It doesn't get much better than this."

The Robert Cray Band will be performing at the Payomet Performing Arts Center, in North Truro, Mass., on Tuesday, Aug. 29, beginning at 7 p.m. Tickets are still available.

Payomet is celebrating its 25th year in 2023 as one of the Cape's leading producers of live music, circus, theatre, and humanities.

The next Target Ship Radio show will be on Sunday, Aug. 20 at 1-4 p.m. The live broadcast can be heard on 92.1 FM Provincetown, and 91.3 FM Orleans, streaming on womr.org and beaming on the free WOMR app.

Is it worth it?

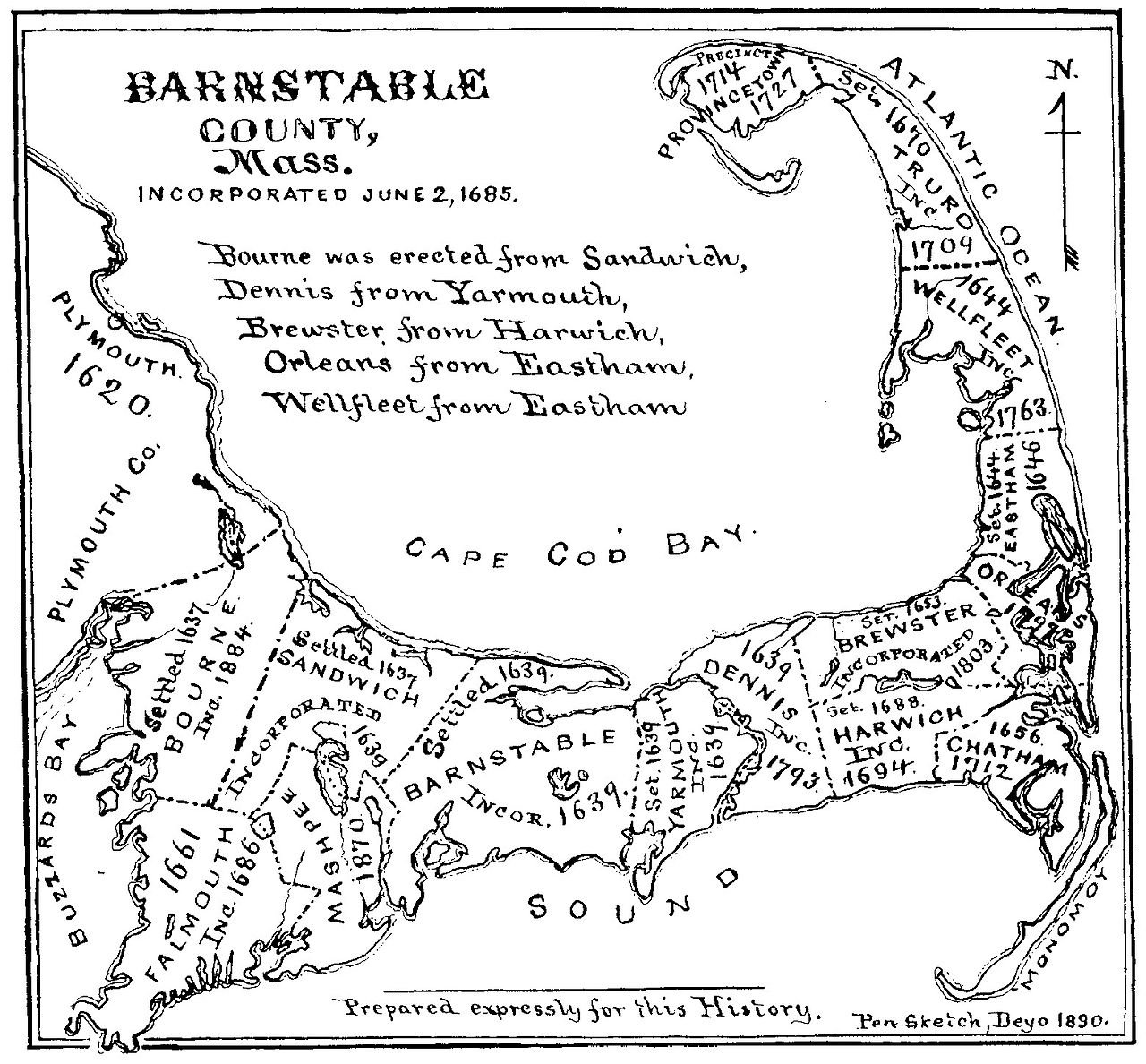

—Map by Kelisi

Adapted from Robert Whitcomb’s “Digital Diary,’’ in GoLocal24.com

“Yet each man kills the thing he loves….”

-- Oscar Wilde (1854-1900), Anglo-Irish playwright and poet

Poor old Cape Cod, once rural and now exurban and suburban.

There’s not enough money at the moment to replace the old (from the 1930s) and too narrow Sagamore and Bourne bridges. And pollution from septic systems, fertilizers and pesticides (lawns and golf courses are major sources) kills life in many freshwater ponds. There are 42 golf courses on the skinny glorified sand bar we call Cape Cod!

What to do? Year-round passenger-train service to reduce car traffic to and fro and on the peninsula? (This would be via the charming railroad bridge over the Cape Cod Canal.) A Barnstable County-wide bond issue to pay to extend sewerage? Close some golf courses

Expand and contract

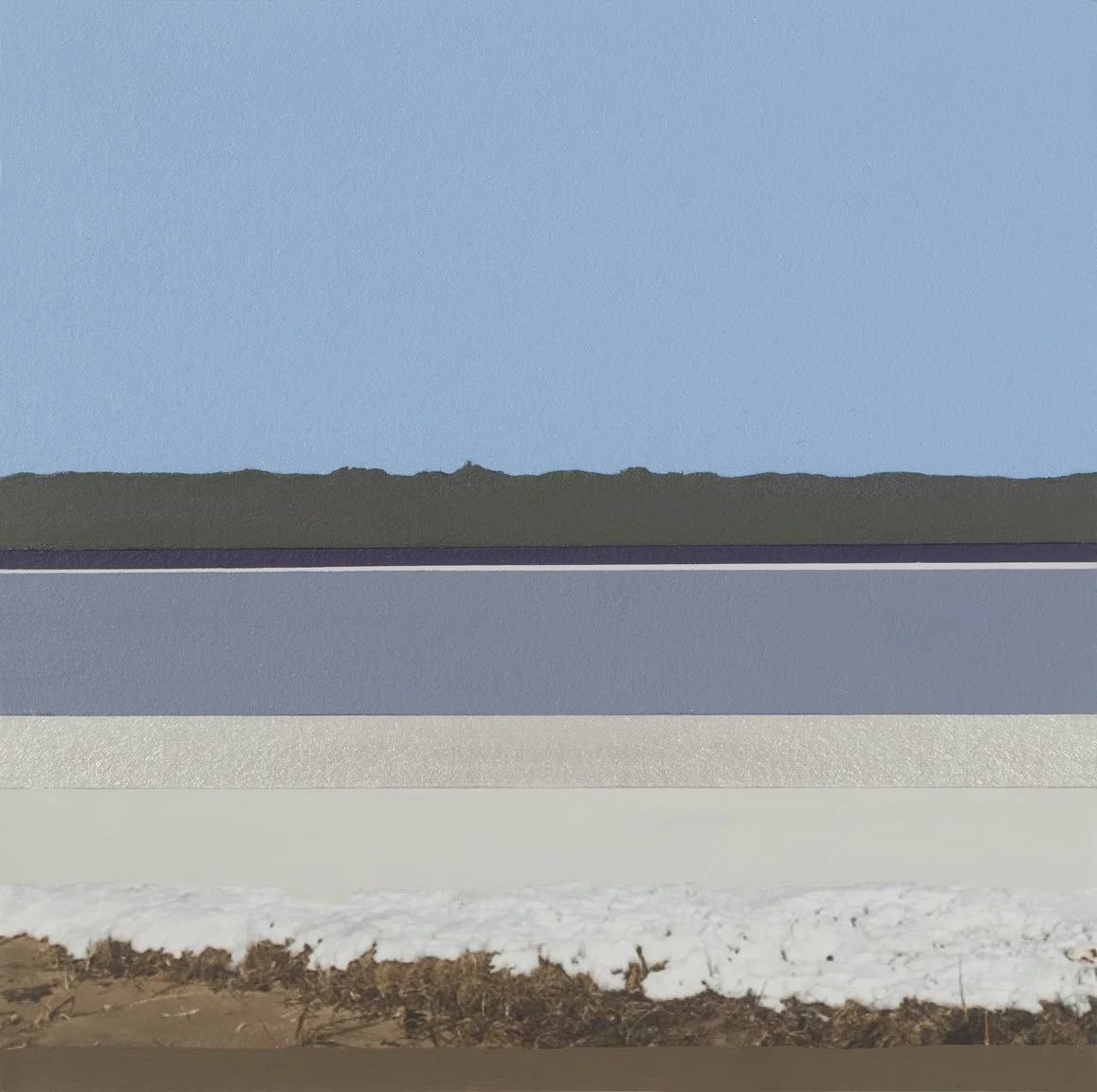

“Edge of Snow” (acrylic and photo on paper), by Cape Cod-based Jane Lincoln, at Kingston Gallery, Boston.

Visit in a storm

At the Cape Cod National Seashore.

“What are springs and waterfalls? Here is the spring of springs, the waterfall of waterfalls. A storm in the fall or winter is the time to visit it; a light-house or a fisherman's hut the true hotel. A man may stand there and put all America behind him.’’

— Henry David Thoreau (1817-1862), in Cape Cod

Provincetown in Thoreau’s lifetime.

In trouble

“I'll tell you the story. I was walking

the outer edge of the outer lands

where sporadic signs staked in dunes

warned to keep distant from the mammals;

in fact, there were critical acts in place

to enforce non-molestation,

but between me and the sea

a seal appeared to be having a time of it….’’

— From ‘“Outer Lands” {on Outer Cape Cod}, by Bill Carty

Why we need schedules

Annie Dillard.

— Photo by Phyllis Rose

At Wesleyan University, in Middletown, Conn. The view from Foss Hill: From left to right: Judd Hall, Harriman Hall (which houses the Public Affairs Center), and Olin Memorial Library

“How we spend our days is, of course, how we spend our lives. What we do with this hour, and that one, is what we are doing. A schedule defends from chaos and whim. It is a net for catching days. It is a scaffolding on which a worker can stand and labor with both hands at sections of time. A schedule is a mock-up of reason and order—willed, faked, and so brought into being; it is a peace and a haven set into the wreck of time; it is a lifeboat on which you find yourself, decades later, still living.”

―Annie Dillard (born 1945), in The Writing Life. The American author of fiction and nonfiction books taught for 21 years at Wesleyan and has long had a summer house on Outer Cape Cod, a place that she has frequently written about.

Summertime, and the living is easy?

— Photo by Robert Jack

Adapted from Robert Whitcomb’s “Digital Diary,’’ in GoLocal24.com

I suspect that many year-round residents of, say, Newport and Cape Cod are already impatiently counting the days until the summer residents and vacationers leave, despite all the money they bring in (along with resort area gridlock).

Despite some brief thunderstorm-spawned downpours, much of New England is in a moderate drought. But there can be a good side to this: Fruits such as apples, grapes (ask wine makers) and peaches are a little smaller than usual but tastier in dry (but not too dry) summers.

Meanwhile, New Englanders should be thankful that its big sources of publicly owned fresh water, such as the Quabbin and Scituate reservoirs, are in no danger of drying up, unlike the water disaster Out West, which may well eventually lead to massive migration to wetter and cooler places.

And now the lilies are wilting along the roads. While global warming is extending our summers, if you’re over a certain age they still seem to go by a bit faster every year.

With New England’s hurricane season coming (mostly August and September), people in such low-lying places as Barrington and Warren, R.I. and the head of Buzzards Bay might want to consult a book I’ve mentioned here before that tells of how some of us will have to learn how to live not only along the water but over the water as seas continue to rise with global warming. The book, again, is More Water Less Land New Architecture: Sea Level Rise and the Future of Coastal Urbanism, by architect Weston Wright.

The beautiful Quabbin Reservoir, in central Massachusetts. Copious fresh water is more valuable than copious petroleum.

— Photo by Solarapex

Before the deluge

“The time must come when this coast (Cape Cod) will be a place of resort for those New-Englanders who really wish to visit the sea-side. At present it is wholly unknown to the fashionable world, and probably it will never be agreeable to them. If it is merely a ten-pin alley, or a circular railway, or an ocean of mint-julep, that the visitor is in search of, — if he thinks more of the wine than the brine, as I suspect some do at Newport — I trust that for a long time he will be disappointed here. But this shore will never be more attractive than it is now.”

— Henry David Thoreau (1817-1862), in Cape Cod (published in 1865)

The dunes on Sandy Neck, in the town of Barnstable.

— Photo by Mr Senseless

Irritating and beautiful

New growth and pollen cones of a pitch pine, a common tree on Cape Cod. It’s very flammable.

— Photo by Famartin

“Now I know summer is here, no matter how cold it is at night, for when I went out to the car this morning, the windshield was dusted with orange and the whole shiny dark blue of the body was powdered. The pine pollen has come! This is a thick, almost oily deposit that penetrates everything. If you close a room and lock the windows, the sills will be drifted with the pollen the next morning. The floors turn orange.’’

— Gladys Taber, in My Own Cape Cod (1971)

Todd McLeish: Seeking strategies for sustaining bay scallops

Bay scallop staring at you with its blue eyes

From ecoRI News (ecori.org)

In the Great Salt Pond on Block Island, native bay scallops are thriving like nowhere else in Rhode Island. Scientists from The Nature Conservancy survey the 673-acre tidal harbor every autumn and have recorded hundreds of scallops each year, despite as many as 50 recreational shellfishermen harvesting scallops from the pond each November and December.

The same cannot be said of the rest of the Ocean State’s waters, however, where bay scallops are few and far between.

On Block Island, Diandra Verbeyst leads a three-person team of Nature Conservancy scuba divers and snorkelers who monitor 12 sites around the Great Salt Pond. They have counted an average of 225 scallops annually since 2016, up from just 44 observed by previous observers in 2007, the first year of monitoring.

“There are slight rises and falls from year to year, but the population is pretty stable,” Verbeyst said. “Based on the 12 sites we monitor, the population is indicating that there is spawning happening each year, and there is recruitment to the population.”

In addition to scallop data, Verbeyst and her team also collect information on water quality and other environmental conditions during their surveys.

“The scallops are an indication that the ecosystem is healthy and doing well, and for me, that’s fascinating in itself,” she said. “No matter where you are in the pond, there’s a good chance you’ll see a scallop.”

Bay scallops are bivalve mollusks with 30-40 bright blue eyes that live in shallow bays and estuaries up and down the East Coast, preferring habitats where eelgrass is abundant. They are short-lived animals — most don’t live more than two years — and are significantly smaller than sea scallops, which are found farther offshore and are harvested by the millions by New Bedford-based fishermen.

Chris Littlefield, a Nature Conservancy coastal projects director and former part-time shellfisherman on Block Island, recalled collecting scallops as a child in the Great Salt Pond 50 years ago, and he has been gathering them in small numbers for his family’s consumption ever since. He said the scallop population received a boost in 2010, when immature scallops grown at the Milford {Conn.} Laboratory of the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration were dispersed into the pond in a project funded by the Natural Resources Conservation Service.

“That project broke through some kind of threshold,” Littlefield said. “Scallops weren’t as abundant before that, and they used to be confined to certain key locations and that was it. But now they’re more abundant and more people are finding them and harvesting them.”

Unlike Nantucket, Martha’s Vineyard and a few locations on Cape Cod and Long Island, where regular seeding of immature bay scallops has resulted in thriving commercial fisheries, Rhode Island has a tiny commercial fishery for bay scallops — fewer than three fishermen participate — and the fishery is not sustainable.

Anna Gerber-Williams, principal marine biologist for the Rhode Island Department of Environmental Management’s Division of Marine Fisheries, just completed the first year of a three-year effort to assess the state’s bay scallop population. She is focused primarily on the salt ponds in South County, especially Point Judith Pond and Ninigret Pond, which historically had healthy bay scallop populations.

“We manage and regulate the bay scallop harvest, but besides Block Island, we haven’t had an actual assessment of what the population looks like in Rhode Island,” Gerber-Williams said. “We know it’s pretty low, and we know the actual commercial harvest numbers are very low. But we don’t have anything to base our management on. The hope is that this project can turn into more long-term monitoring, similar to what’s done on Block Island, and maybe lead to restoration efforts.”

Based on her first year of surveys, Gerber-Williams said there are self-sustaining populations of bay scallops in Point Judith Pond, and their abundance can fluctuate significantly from year to year.

“Scallops are very habitat-dependent,” she said. “The habitat in the salt ponds is very patchy, and those patches are very small.”

Unlike clams, which bury themselves in the sand, bay scallops sit on the seafloor and can swim around by rapidly opening and closing their shell, making them difficult to track and count. Gerber-Williams said they are threatened by several varieties of crabs, which can easily crush the scallops’ shells with their claws.

“Part of the scallop’s strategy is to hide from the crabs in the eelgrass,” she said. “When they’re younger, they attach themselves to eelgrass blades to keep themselves above the bottom and out of reach of predators.”

Dan Torre at Aquidneck Island Oyster Co. experimented this year with growing bay scallops in cages in the Sakonnet River off Portsmouth. He bought scallop seed from area hatcheries last July, and they are approaching marketable size now. He has contracted with one local restaurant to buy his experimental crop, with hopes of scaling up the operation next year.

“I believe there’s a market, but it’s a niche market,” he said. “Normally with sea scallops, you sell just the shelled adductor muscle, but with bay scallops you sell the whole animal. The shelf life isn’t the longest, but it seems like there are a bunch of restaurants that are eager to try them.”

In an effort to figure out how best to restore wild bay scallop populations in the region, the Rhode Island Commercial Fisheries Research Foundation is collaborating with The Nature Conservancy to synthesize what is known about the history of the bay scallop population and fishery in Point Judith Pond.

According to Dave Bethoney, the foundation’s executive director, it will be combined with information about scallop fisheries in Massachusetts and Long Island, N.Y., as a first step to developing a restoration plan.

“How to make them sustainable is the real puzzle,” Bethoney said. “Even successful efforts on Long Island are based on a seeding plan — getting scallops every year from aquaculture facilities to replenish them. They have successful populations, but they’re not self-sustaining. I don’t know how we change that.”

Gerber-Williams agreed.

“In my opinion, the way to boost populations here and keep them at a level that’s sustainable for a good fishery in Rhode Island, we would have to have a seeding program similar to what they have in Long Island and Martha’s Vineyard,” she said. “Every year they put out thousands of baby bay scallops. They seed their salt ponds every single year to keep a decent fishery going.

“So the next step for us would be to do that kind of seeding program in Rhode Island. We’re in the process of creating a restoration plan for various species of shellfish in Rhode Island, and my hope is that bay scallops are a part of that.”

Hopefully the current researchers go back to the North Cape shellfish injury restoration project, which included release of bay scallop seed into the South County salt ponds, to learn about what worked or did not work for the multi-year that wrapped up by 2010. The reports are available and some of us who worked on the project are available to discuss challenges and successes.

Todd McLeish is an ecoRI News contributor.

Eelgrass is prime habitat for bay scallops.

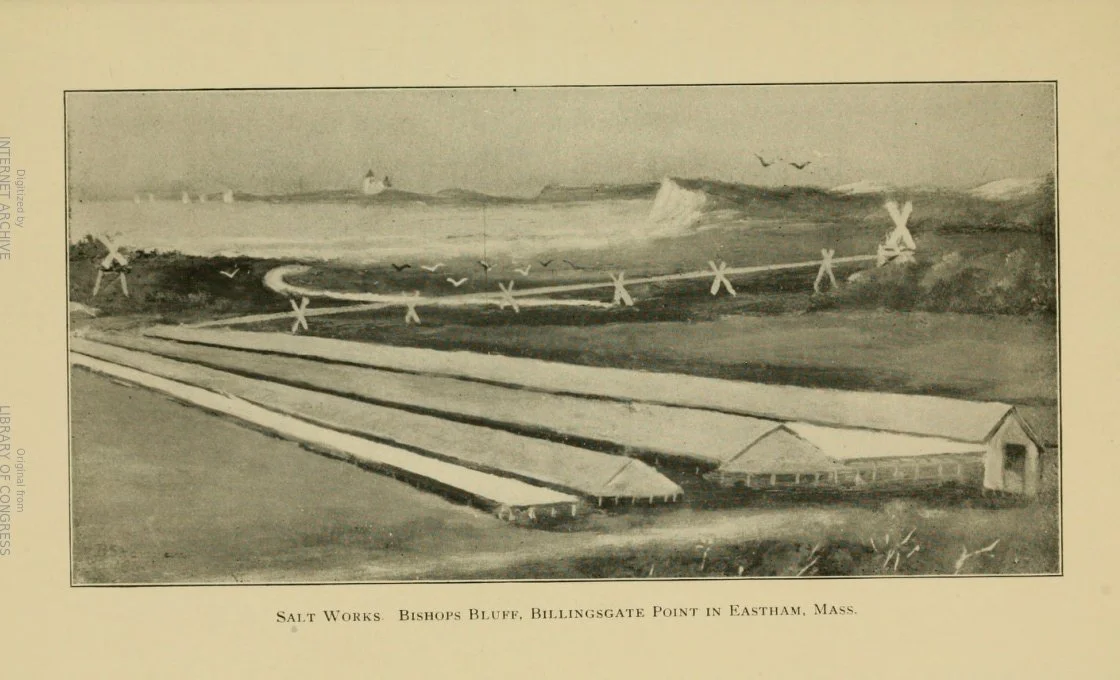

Old salts

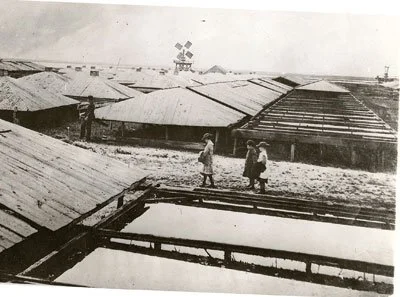

West Yarmouth salt works in the 19th Century.

Adapted from Robert Whitcomb’s “Digital Diary,’’ in GoLocal24.com

Some of my ancestors were in the salt business on Cape Cod in the 19th Century; they made it from evaporating ocean water. It seems so long ago that large amounts of such a basic commodity, like ice cut from ponds in Maine, would be produced in low-tech ways in New England, for the local and faraway markets. (Blocks of ice from New England would be packed in sawdust and shipped by boat to the Southeast.)

The smarter relatives moved money that they made from this commerce into more lucrative manufacturing of shoes, tools and so on. A few even straggled into mid-20th Century high tech. Of course, all sectors fade in the end.

Raking up the sun

“Dune Shadows: Hyannis, Cape Cod’ (archival pigment print), by Bobby Baker

© Bobby Baker Fine Art

Before the summer folks

Provincetown, at the tip of Cape Cod, in the years when Thoreau walked the peninsula— 1849, 1850 and 1855.

“The time must come when this coast (Cape Cod) will be a place of resort for those New-Englanders who really wish to visit the sea-side. At present it is wholly unknown to the fashionable world, and probably it will never be agreeable to them. If it is merely a ten-pin alley, or a circular railway, or an ocean of mint-julep, that the visitor is in search of, — if he thinks more of the wine than the brine, as I suspect some do at Newport, — I trust that for a long time he will be disappointed here. But this shore will never be more attractive than it is now.”

Henry David Thoreau (1817-1862) in Cape Cod, first published in 1865, soon before railroads started to make The Cape a major summer-resort area.

At New Silver Beach, in Falmouth, on the western side of The Cape — probably not quite what Thoreau could have foreseen.

‘She gives of her strength’

“Hold your hands out over the earth as over a flame. To all who love her, who open to her the doors of their veins, she gives of her strength, sustaining them with her own measureless tremor of dark life.’’

— Henry Beston (1888-1968), American writer and naturalist, in The Outermost House, the classic story of the time he spent living alone in a shack on Cape Cod’s Nauset Beach.

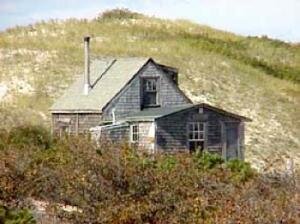

When summer was long

One of the “Dune Shacks’’ of Peaked Hill Bars Historic District in Provincetown and Truro, on outer Cape Cod. The shacks include those that have been home to American painters and writers from the 1920s to the present day.

“Bring back the long summer after fourth grade

with stinging-cold waves the crashed on the Cape,

the tall, white dunes we scrambled across….’’

— From “Album,’’ by Gardner McFall (born 1952), an American poet

Smith’s 'meditations on land, water and air'

“Stream No. 31” (chromogenic print), by British-born (but now of Brooklyn) photographer Jonathan Smith, in his show at Lanoue Gallery, Boston, through May 23.

The gallery says:

Jonathan Smith spent the early years of his career assisting and printing for the renowned photographer Joel Meyerowitz {famous for his photos of Cape Cod}, and has had solo exhibitions in both nationally and internationally. His work consists of large-scale, highly nuanced color photographs of the stark natural beauty and inherent impermanence of landscapes.

“Smith has been photographing natural landscapes for more than 15 years. Shooting precisely and selectively with incredible detail, often revisiting the same site on several occasions until he feels the essential character of the landscape has been revealed to him. This conscious and gradual process of documentation results in meditations on land, water and air.’’

His investigations of landscape have led him to the remote locations of northern Iceland and southern Patagonia, where he photographed streams, glaciers, glacial rivers and waterfalls. These landscapes, devoid of human presence, display a world lost in time. Often abstracted, these photographs of mountain streams and glacial shifts are a reminder of the forces of nature at play; a sublime beauty far removed from the everyday. Drifting into frame, the dreamlike palette of these landscapes offers a window into an ephemeral world where scale and perspective become impalpable. These landscapes inspired the creation of large-scale prints that echo the vastness of the spaces they depict, inviting the viewer in to contemplate their own relationship to the natural world.

Above: Stream No. 31, chromogenic print, available sizes: 30x37.5" ed. of 8, 40x50" ed. of 5, 56x70" ed. of 3

The Cape: Still beauty amongst the McMansions

Sesuit Creek, in East Dennis

From Robert Whitcomb’s “Digital Diary,’’ in GoLocal24.com

David Gessner’s 1997 book, A Wild, Rank Place, is a series of essays about, among other things, how Cape Cod has become exurbanized, such as with grotesque show-off McMansions replacing the low-to-ground, modest gray-shingled houses so identified with the Cape. And yet he can still savor its remaining windy and haunting beauty. It’s a subject that particularly appealed to me because part of my family were/are old Cape Codders; I’ve seen even more change than he has.

Mr. Gessner (born in 1961) lived off and on for years in a family summer house in East Dennis (sold a few years ago). It was the heart of his family.

The title is a phrase by Henry David Thoreau based on several trips he took to the Cape in the early 1850s that resulted in the book of essays called Cape Cod. But as Mr. Gessner’s book notes, Thoreau’s deforested Cape looked a lot different than it did in the 1600s, when the English arrived, and of course much different than the current version, where woods have grown back even as the number of houses and convenience stores explodes and car traffic worsens virtually every year.=

There is vivid and idiosyncratic nature and environmental writing here, mixed with an intense family memoir whose heart is Mr. Gessner’s effort to come to terms with the transitory nature of life, and especially mortality, and entropy, with his father’s fatal illness at the center of all that. There are also some charming pen-and-ink drawings by Mr. Gessner, who is a cancer survivor.

Lonely in the universe

Tideline in North Truro

Photo by Hqfrancis

….this is just one sea

on one beach on one

planet in one

solar system in one

galaxy. After that

the scale increases, so

this not the last word,

and nothing else is talking back.

It’s a lonely situation.’’

— From The Sea Grinds Things Up,’’ by Alan Dugan (1923-2003), a Pulitzer Prize-winning poet. He lived in Truro, on Outer Cape Cod. The town, as with Provincetown, just to the north, has long drawn artists of various kinds, along with other exotic tribes, such as New York City psychoanalysts.