Study is aimed at protecting right whales in offshore windpower areas

North Atlantic right whale mother with calf

From ecoRI News (ecori.org)

Ørsted is funding a project to study and protect endangered North Atlantic right whale during surveys, construction and operation of its U.S. offshore wind facilities such as Bay State Wind and Revolution Wind.

Using data collected from an aerial, unmanned glider and two sound-detection buoys, researchers from the University of Rhode Island, Rutgers University and the Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution will examine the habitat and behaviors of right whales in the wind-lease areas awarded to Ørsted.

An estimated 400 North Atlantic right whales remain, fewer than 100 are breeding females.

The oceanographic data will help studies of additional fish species and improve forecasting for severe storms and other weather, according to Ørsted. The three-year initiative is called Ecosystem and Passive Acoustic Monitoring (ECO-PAM).

Vineyard Wind watch

A key offshore wind report is expected this week from the Coast Guard. The draft of the Massachusetts and Rhode Island Port Access Route Study (MARIPARS) will recommend wind farm layouts, spacing, and transit lanes for vessel safety, navigation, and search-and-rescue operations.

The draft report will be followed by a 45-day comment period. The Coast Guard is expected to finalize the report in April.

At its nearest point, the Vineyard Wind project is about 14 miles from the southeast corner of Martha’s Vineyard and a similar distance from the southwest side of Nantucket. (BOEM)

At its nearest point, the Vineyard Wind project is about 14 miles from the southeast corner of Martha’s Vineyard and a similar distance from the southwest side of Nantucket. (BOEM)

The recommended wind-facility grid is expected to inform the forthcoming draft environmental impact statement (EIS) from the Bureau of Ocean Energy Management (BOEM) for the Vineyard Wind project. If adopted by BOEM, MARIPARS will accelerate other wind proposals in the federal lease areas off southern New England.

BOEM won’t give any hints about when it will release the expanded EIS for the Vineyard Wind project. BOEM media representatives will only say to look for updates at its Vineyard Wind Web site.

The expanded EIS will focus on fishing and other impacts of offshore wind development in the region. The initial EIS was expected by the end of last year but pushed until early 2020.

The initial EIS was delayed last summer after the National Marine Fisheries Service and the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration declined to endorse the report.

After hearings and a public comment period on the upcoming EIS, a record of decision from BOEM on the Vineyard Wind project isn’t likely until December. If approved, major work on the 800-megawatt wind facility, such as pile driving, can’ commence until May 1, 2021. An agreement to protect North Atlantic right whales with three environmental groups signed last year prohibits such work between January and April.

Foster wind moratorium

The Foster (R.I.) Town Council recently approved a 180-day moratorium on wind-turbine development. There are no proposals before the town, but the council wants to give the Planning Board time to write an ordinance for future wind development.

“There’s speculation whether companies would be interested in coming into our town and we want to make sure we had things in order,” Town Council president Denise DiFranco said at the council’s Jan. 23 meeting.

The council can extend or shorten the moratorium. Residential wind systems less than 100 kilowatts are still permitted.

Virginia wind

Virginia is upping its involvement in offshore wind with a vision to reach World War II levels of maritime industrial activity. Last September, Dominion Energy, the owner of natural-gas pipelines and power plants, including the Manchester Street Power Station, in Providence, announced plans for a 2,600-megawatt wind facility off Virginia Beach. Gov. Ralph Northam has since set a state energy target of 30 percent renewable power by 2030 and 100 percent by 2050.

Dominion is also developing a two-turbine offshore test site called the Coastal Virginia Offshore Wind Project with Ørsted. The project could be operational by late this year.

Like many states in the Mid-Atlantic and Northeast, Virginia wants to expand its ports to build maritime centers for wind turbine construction, maintenance, and shipping. An estimated 14,000 jobs could be created by the new maritime industries in the state.

Tim Faulkner is an ecoRI News journalist.

Tim Faulkner: Future of offshore wind hangs on agency's report

Progression of expected wind turbine evolution to deeper water

From ecoRI News

The forthcoming report from the federal Bureau of Ocean Energy Management (BOEM) on the cumulative environmental impacts of the Vineyard Wind project will determine the future of offshore wind development.

BOEM’s decision isn’t just the remaining hurdle for the 800-megawatt project, but also the gateway for 6 gigawatts of offshore wind facilities planned between the Gulf of Maine and Virginia. Another 19 gigawatts of Rhode Island offshore wind-energy goals are expected to bring about more projects and tens of billions of dollars in local manufacturing and port development.

Some wind-energy advocates have criticized BOEM’s 11th-hour call for the supplemental analysis as politically motivated and excessive.

Safe boat navigation and loss of fishing grounds are the main concerns among commercial fishermen, who have been the most vocal opponents of the 84-turbine Vineyard Wind project and other planned wind facilities off the coast of southern New England.

Last month, Rhode Island state Sen. Susan Sosnowski, D-New Shoreham and South Kingstown, gave assurances that the Coast Guard will not be deterred from conducting search and rescue efforts around offshore wind facilities, as some fishermen have feared.

“The Coast Guard’s response will be a great relief to Rhode Island’s commercial fishermen,” Sosnowski is quoted in a recent story in The Independent. “We have many concerns regarding navigational safety near wind farms, and that was the biggest.”

The anticipated release of the BOEM report coincides with President Trump’s efforts to weaken environmental impact reviews for all energy proposals, including wind, coal, and natural gas. National Environmental Policy Act (NEPA) reviews have slowed pipeline projects such as Keystone XL and, as of last summer, Vineyard Wind. Both industries praised the move to loosen environmental rules. Environmentalists, meanwhile, fear that the removal of terms such as “cumulative,” "direct," and "indirect" from NEPA’s directives will nullify future federal efforts to address the climate crisis.

Once the expanded environmental impact statement is released, BOEM will offer a comment period and hold public hearings

Stephens leaves Vineyard Wind

Barrington native and Providence resident Erich Stephens resigned at the end of 2019 from Vineyard Wind, a company he helped found in 2009 and is now co-owned by Avangrid and Copenhagen Infrastructure Partners. The original wind company was called Offshore MW. Prior to Vineyard Wind, Stephens was head of development for Bluewater Wind, one of the first U.S. offshore wind companies.

Stephens has considerable roots in Rhode Island. He attended Barrington High School and received his undergraduate degree from Brown University. He was founder and executive director of People’s Power & Light, now called the Green Energy Consumers Alliance. He was also a founding partner of Solar Wrights, a residential solar company that was based in Barrington and moved to Bristol. The company was later acquired by Alteris Renewables. Stephens also worked for two of Rhode Island’s first oyster farms.

More megawatts

New York plans to add 1,000 megawatts of offshore wind power to the 1,700 megawatts it awarded last summer to offshore wind projects that will deliver electricity to Long Island and New York City.

The state also announced it’s taking bids for $200 million in port development projects that will support the offshore wind industry.

The recent notifications are part of the state’s Green New Deal, which aims for 9 gigawatts of offshore wind by 2035 and 20 large solar arrays, battery-storage facilities, and onshore wind turbines in upstate New York. The state aims for 100 percent renewable energy by 2040.

The latest offshore wind projects consist of the 880-megawatt Sunrise Wind facility, developed by Ørsted and Eversource Energy, to power Manhattan. Long Island will receive up to 816 megawatts from the Empire Wind facility, developed by Equinor of Norway.

Pricing for the projects hasn’t been made public.

Offshore leader

Based in Denmark, Ørsted is the early leader in the size and number of U.S. offshore wind projects. Ørsted was awarded the 400-megawatt Revolution Wind project for Rhode Island. It’s also developing the 1,100-megawatt Ocean Wind facility in New Jersey, a demonstrations project in Virginia, and projects in Connecticut, Delaware, Massachusetts, and Maryland. The company acquired Providence-based Deepwater Wind in 2018 for $510 million.

Ocean Wind, New Jersey’s first offshore wind project, and the 120-megawatt Skipjack Wind Farm off Maryland will use General Electric’s huge 12-megawatt Haliade-X turbines. The 853-foot-high turbines are the tallest in production and have twice the capacity of the 6-megawatt GE turbines now spinning off Block Island, which are 600 feet tall.

Tim Faulkner is a journalist with ecoRI News.

Frank Carini: Oil dumping continues to mar New Bedford Harbor

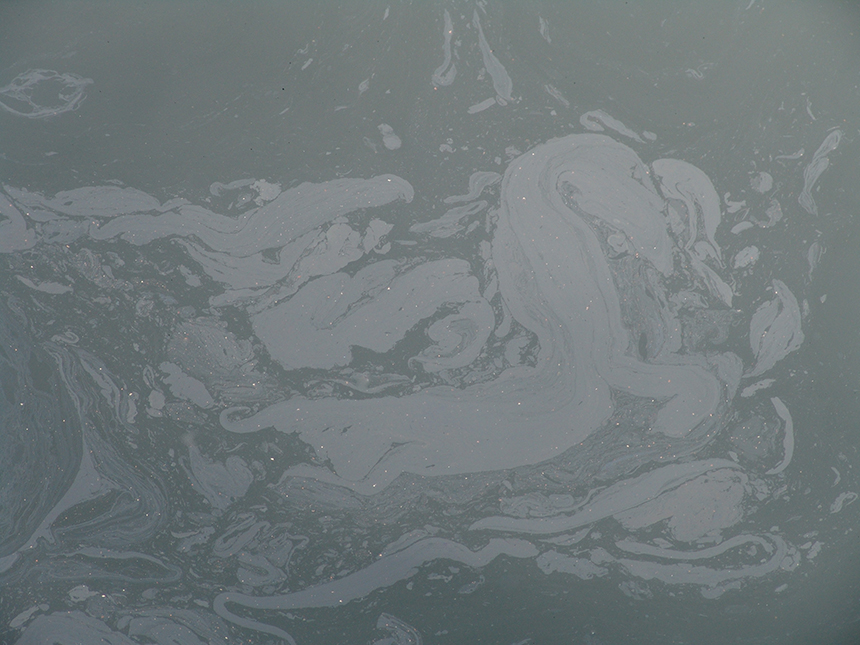

A weirdly beautiful oil sheen on the waters of New Bedford Harbor.

Photo by Frank Carini

From ecoRI News (ecori.org)

NEW BEDFORD, Mass.

Oil sheens have long stained one of the country’s most historic harbors. Visits by tourists to enjoy seaside sights and sample local seafood at harborside restaurants can be marred by these distinct marine markings.

In late February, the Coast Guard and Massachusetts Department of Environmental Protection (DEP) were called to New Bedford Harbor after oil was spotted lapping up against the docks and fishing vessels at Leonard’s Wharf. About two drums worth of oil was recovered. The source was never identified.

Six months later, in mid-August, Coast Guard crews oversaw a fuel-spill cleanup after a tugboat captain called the Coast Guard to report a 62-foot fishing vessel had sunk and was discharging fuel. The vessel carried about 7,000 gallons of fuel. The spill spread some 1.5 miles to Fairhaven.

Since 2010, the marine-industrial harbor has seen at least one recorded oil spill every month, according to the Buzzards Bay Coalition.

“New Bedford Harbor has a chronic oil spill problem,” a Coast Guard press release noted earlier this year.

The harbor’s spill problem doesn’t mix well with a 2009 study titled “Evaluation of Marine Oil Spill Threat to Massachusetts Coastal Communities,” which noted that, “New Bedford Harbor reported the highest number of vessels, with a fleet size of 500, many of which are large offshore scallopers and draggers. The GPE (gallons of petroleum exposure) for the New Bedford Harbor fishing fleet is estimated at 7,500,000 gallons, more than three times the next largest amount.”

Much of the Port of New Bedford’s petroleum problems can be traced back to the accidental and intentional dumping of oil via bilge water from commercial fishing vessels. Fuel and oil can leak into a vessel’s bilge, or the engine block can be deliberately drained into the bilge. This mixture of water, oil and fuel is released into the marine environment when an automatic bilge pump turns on, or when a boat owner deliberately breaks the law and pumps the bilge out in the harbor or out at sea. It's been a problem for decades.

These chronic oil discharges have been a longtime concern for Joe Costa, executive director of the Buzzards Bay National Estuary Program. The 1991 Comprehensive Conservation and Management Plan (CCMP) for Buzzards Bay highlighted the problem. It remained an identified concern in the 2013 Buzzards Bay CCMP.

It remains a concern today. Since 2016, more than 70 oil sheens have been reported in the water between New Bedford and Fairhaven. In most cases, no one steps forward to claim responsibility, according to the Coast Guard’s New Bedford field office.

Port director Edward Anthes-Washburn acknowledged that the problem is exacerbated when ships pump out contaminated bilge water.

“We have a concentration of vessels like nowhere else on the East Coast,” he said, noting that the working harbor is the home port of 300 fishing vessels and services another 200. “There’s no doubt bilge water is an issue. We’re working on education, and reporting spills.”

Anthes-Washburn, who also serves as the executive director of the New Bedford Harbor Development Commission (HDC), noted that fuel barges operated by oil retailers pump out waste oil for free, as long as it’s not contaminated by seawater.

And therein lies the real issue: too many owners fail to properly maintain their vessels, some of which are 20 to 30 years old. Advocates for a cleaner harbor believe the city needs to be more actively engaged in implementing a solution.

For instance, the HDC’s Fishing for Energy program collects derelict fishing nets and burns them for fuel. But the program doesn’t accept hazardous waste such as used oil contaminated by salt water.

“This problem has been worked on for 30 years and the ending is always the same: nothing gets done,” said Dan Crafton, section chief of emergency response for DEP’s Lakeville, Mass.-based unit. “The city doesn’t want to do anything to increase the burden on fishermen. But there are necessary components to running a clean harbor.”

Slow motion

As far back as the early 1990s, the reduction of discharges of oil and other hydrocarbons into New Bedford Harbor was identified as a high priority. The 1991 Buzzards Bay CCMP noted:

“Commercial fishing vessels, which operate mostly out of New Bedford but also Westport, usually have their engine oil changed (10-120 gallons per boat) after practically every trip. It is believed that the inconvenience and the expense (about 30 cents per gallon) of safely disposing of waste oil has resulted in a number of boat operators blatantly dumping oil into the Bay or offshore waters.”

The 270-page report also noted that, “Although this is illegal, it is difficult to document violations and hence take enforcement actions against the appropriate fishing boats.”

A January 1993 report titled “New Bedford Harbor Marine Pump-Out Facilities Study” and prepared for the HDC by HMM Associates Inc. noted that the disposal of vessel-generated waste oil “is unquestionably the single most important water quality protection initiative that must be implemented by municipal authorities if advances in water quality improvements are to be made within the harbor.”

The report also noted that the “unknown fate of over 252,000 gallons of engine waste oil known to be generated by the home fleet and not collected, is just too important to ignore.”

In 2000, Buzzards Bay National Estuary Program's Costa wrote a proposal titled A Boat Waste Oil Recovery Program for New Bedford Harbor to address the problem and received grant money from two sources. However, the initiative, which included building a bilge-water-oil separation facility along New Bedford’s working waterfront, failed to gain traction, due in large part to a lack of support from local officials. Costa ended up returning the grant money.

Crafton said the city isn't interested in a waterfront bilge-water-oil separator, even if the state funded the upfront costs. The city would have had to provide some operational funding. The cost to boaters to properly dispose of waste oil is about 50 cents a gallon, according to Crafton.

“Jiffy Lube charges car owners to dispose of their waste oil,” he said. “It’s harder to dump oil on the ground and get away with it. Most spills in the harbor happen at night, not during the day. People need to be more environmentally aware.”

Crafton also noted that DEP hasn't been able to find a private property owner interested in hosting a separator facility.

ecoRI News contacted the mayor’s office, but comment for this story was left to the HDC, a city agency. Mayor Jonathan Mitchell is the chairman of the HDC Commissioners.

“Our grant request to DEP for an oil recovery facility will address one major remaining source identified in the CCMP, the accidental and sometimes intentional dumping of tens or hundreds of thousands of oil by commercial vessels via bilge water,” according to Costa’s 17-year-old proposal. “The net environmental benefit of funding this initiative will be the prevention of 100,000 of gallons of oil and hydrocarbons from entering the coastal environment.”

The plan was specifically designed to eliminate “imposing oil disposal costs to an economically disadvantaged fishing industry.” Besides building a bilge-water-oil separation facility, the plan also proposed implementing an oil-recovery recycling program to provide easy and safe disposal of boat engine waste oil, a multilingual outreach/education program, and providing training and assistance to oil retailers.

The 1993 HMM Associates study recommended eight specific actions to address the improper disposal of waste oil, from adopting local regulations requiring oil-free bilges in commercial vessels to creating a private commercial service that would pump out waste oil from commercial vessels free of charge.

Costa’s 2000 proposal noted “little was done to implement these recommendations.” Costa estimated that as much as 60,000 to 120,000 gallons of waste oil are dumped, leaked and spilled into local waters annually by New Bedford Harbor’s commercial fishing fleet.

Today, nearly two decades later, New Bedford’s fishing fleet doesn’t have as many vessels and more boat owners are recycling waste oil properly. But a significant amount of used boat oil, which is considered hazardous waste, is still unnecessarily finding its way into New Bedford Harbor and Buzzards Bay.

Anthes-Washburn said the HDC doesn’t focus on the enforcement of state and federal regulations. He noted that the municipal agency is focused foremost on keeping its customers, the port’s commercial fishing fleet, safe.

“We report everything we see,” he said. “The fleet knows law enforcement is looking at it.”

Those concerned about this marine hydrocarbon problem point to several factors: no identified source or responsible party; poor waste oil management practices; underutilized disposal options; reluctance to report spills; lack of awareness.

“We want to work with fishermen, not against them,” Crafton said. “We’re not trying to harm the fishing industry.”

Addressing the problem

It’s been a while since the practice of pumping contaminated water from the bilges of fishing boats into the ocean has been legal. Under the Federal Water Pollution Control Act, no amount of oil is allowed to be pumped into the sea — understandable, since a cup of oil can create a sheen the size of a football field.

Lt. Lynn Schrayshuen, the Coast Guard’s New Bedford unit supervisor, and her Marine Safety Detachment team patrol New Bedford Harbor regularly looking for spilled, leaked or dumped oil. When an oil sheen is discovered, or reported, the team investigates to determine if it is recoverable, and collects a sample.

Collected samples are taken to the Coast Guard Marine Safety Lab in New London, Conn., for testing. The samples are processed and cleaned of organic material until only oil is left. If the oil fingerprint from the sheen matches the fingerprint from another bilge sample, the team may be able to identify a responsible party.

But the illegal practice, including the common practice of pumping water out from the bilge and then stopping when oil enters the stream, remains a considerable problem for New Bedford Harbor, the city’s coastline, and across the way in Fairhaven.

To deal with the problem, DEP and the HDC ran a pilot program called Clean Bilge New Bedford that offered free pump-outs and inspections to commercial fishing vessels to prevent oil spills, and featured outreach and educational efforts. The 1.5-year pilot, which was state funded, ended earlier this year. During the pilot program, 174 vessels had their bilge pumped out once and 39 had their bilge pumped out at least twice. A total of 58,666 gallons of oily bilge water was recovered — 18,387 gallons, or 31 percent, was oil.

“This is a real issue,” Crafton said. “What would people think if they knew the number one fishing port in the United States is the same place where waste oil is being dumped?”

Frank Carini is editor of ecoRI News (ecori.org)

·

Philip K. Howard: Infrastructure repairs drown in regulatory molasses

To our readers: This column also ran in a pre-renovation version of New England Diary a few weeks ago. As we seek to import the pre-renovation archives, we will rerun particularly important files, such as Philip Howard's piece here.

-- Robert Whitcomb

By PHILIP K. HOWARD

NEW YORK

President Obama went on the stump this summer to promote his "Fix It First" initiative, calling for public appropriations to shore up America's fraying infrastructure. But funding is not the challenge. The main reason crumbling roads, decrepit bridges, antiquated power lines, leaky water mains and muddy harbors don't get fixed is interminable regulatory review.

Infrastructure approvals can take upward of a decade or longer, according to the Regional Plan Association. The environmental review statement for dredging the Savannah River took 14 years to complete. Even projects with little or no environmental impact can take years.

Raising the roadway of the Bayonne Bridge at the mouth of the Port of Newark, for example, requires no new foundations or right of way, and would not require approvals at all except that it spans navigable water. Raising the roadway would allow a new generation of efficient large ships into the port. But the project is now approaching its fifth year of legal process, bogged down in environmental litigation.

Mr. Obama also pitched infrastructure improvements in 2009 while he was promoting his $830 billion stimulus. The bill passed but nothing much happened because, as the administration learned, there is almost no such thing as a "shovel-ready project." So the stimulus money was largely diverted to shoring up state budgets.

Building new infrastructure would enhance U.S. global competitiveness, improve our environmental footprint and, according to McKinsey studies, generate almost two million jobs. But it is impossible to modernize America's physical infrastructure until we modernize our legal infrastructure. Regulatory review is supposed to serve a free society, not paralyze it.

Other developed countries have found a way. Canada requires full environmental review, with state and local input, but it has recently put a maximum of two years on major projects. Germany allocates decision-making authority to a particular state or federal agency: Getting approval for a large electrical platform in the North Sea, built this year, took 20 months; approval for the City Tunnel in Leipzig, scheduled to open next year, took 18 months. Neither country waits for years for a final decision to emerge out of endless red tape.

In America, by contrast, official responsibility is a kind of free-for-all among multiple federal, state and local agencies, with courts called upon to sort it out after everyone else has dropped of exhaustion. The effect is not just delay, but decisions skewed toward the squeaky wheels instead of the common good. This is not how democracy is supposed to work.

America is missing the key element of regulatory finality: No one is in charge of deciding when there has been enough review. Avoiding endless process requires changing the regulatory structure in two ways:

Environmental review today is done by a "lead agency"—such as the Coast Guard in the case of the Bayonne Bridge—that is usually a proponent of a project, and therefore not to be trusted to draw the line. Because it is under legal scrutiny and pressure to prove it took a "hard look," the lead agency's approach has mutated into a process of no pebble left unturned, followed by lawsuits that flyspeck documents that are often thousands of pages long.

What's needed is an independent agency to decide how much environmental review is sufficient. An alteration project like the Bayonne Bridge should probably have an environmental review of a few dozen pages and not, as in that case, more than 5,000 pages. If there were an independent agency with the power to say when enough is enough, then there would be a deliberate decision, not a multiyear ooze of irrelevant facts. Its decision on the scope of review can still be legally challenged as not complying with the basic principles of environmental law. But the challenge should come after, say, one year of review, not 10.

It is also important to change the Balkanized approvals process for other regulations and licenses. These approvals are now spread among federal, state and local agencies like a parody of bureaucracy, with little coordination and frequent duplication of environmental and other requirements. The Cape Wind project off the coast of Massachusetts, now in its 12th year of scrutiny, required review by 17 different agencies. The Gateway West power line, to carry electricity from Wyoming wind farms to the Pacific Northwest, requires the approval of each county in Idaho that the line will traverse. The approval process, begun in 2007, is expected to be complete by 2015. This is paralysis by federalism.

The solution is to create what other countries call "one-stop approvals." Giving one agency the authority to cut through the knot of multiple agencies (including those at state and local levels) will dramatically accelerate approvals.

This is how "greener" countries in Europe make decisions. In Germany, local projects are decided by a local agency (even if there's a national element), and national projects by a national agency (even though there are local concerns). One-stop approval is already in place in the U.S. New interstate gas pipelines are under the exclusive jurisdiction of the Federal Energy Regulatory Commission.

Special interests—especially groups that like the power of being able to stop anything—will foster fears of officials abusing the public trust. Giving people responsibility does not require trust, however. I don't trust anyone. But I can live with a system of democratic responsibility and judicial oversight. What our country can't live with is spinning our wheels in perpetual review. America needs to get moving again.

Philip K. Howard, a lawyer, is chairman of the nonpartisan reform group Common Good. His new book, "The Rule of Nobody," will be published in April by W.W. Norton. He is also the author of, among other works, "The Death of Common Sense''.