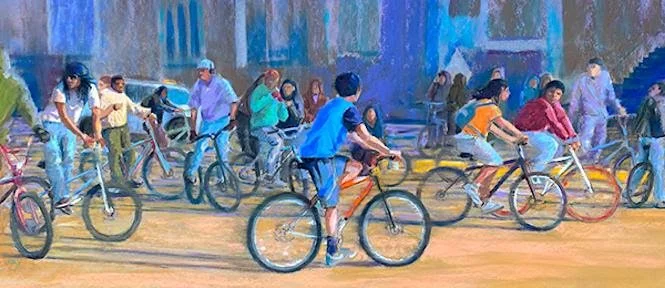

Bumping bikes

“Propelled” (pastel), by Plymouth, Mass.-based Jory Mason, in the group show “Signature Strokes,’’ at the South Shore Art Center, Cohasset, Mass., through Oct. 28., in collaboration with the Pastel Painters Society of Cape Cod and juror Lisa Flynn.

The arts center says the show features pastel artwork of “everything from natural scenes of plants, water and delicate flowers to subjects including men at work repairing a city street and the rough moorings of a ship.’’

Recreation of Plimoth Plantation, at Plymouth

— Photo by Marco Almbauer

Small-town presidential politics

Cohasset Town Common, with Congregational church in the center background and the Unitarian church partly obscured by trees at left.

—Photo by Wwoods

Adapted from Robert Whitcomb’s “Digital Diary,’’ in GoLocal24.com

I rather fuzzily remember a flag-filled, informal motorcade in Cohasset, Mass., in 1956 for “Eisenhower for President’’. It was a fresh late-October day, with a northwest wind pulling the remaining red and orange leaves off the maples and the muted yellow ones off the hour-glass-shaped elms, of which we still had many, although Dutch elm disease was rapidly killing them off. Kids and their young parents applauded alongside the road.

We proceeded in our station wagon over a little bridge near the harbor and headed toward the classic town common (you can see it in The Witches of Eastwick), with the little pond with a fountain on a rock island in the middle of it. At the common, I recall, a generally genteel GOP campaign rally took place.

On two sides of the common were the two very white (in two senses of the word) Unitarian and Congregational churches. Nearby, on top of a granite outcropping, presided the neo-Gothic St. Stephen’s Church, a monument of the WASP upper-middle and upper class in the rather WASPY town. The local clan who owned much of Dow Jones & Co. had financed much of its building. See picture below of St. Stephen’s aristocratically looming over Cohasset’s downtown, next to the common.

The old line about the Episcopalians was “the Republican Party at prayer.’’ No more.

The town’s Catholic church, St. Anthony, was a few blocks away, in that still majority Protestant town. Its parishioners were generally of Irish, Italian and Portuguese background. We Protestants felt sorry for the Catholic kids because they had to go to catechism and confession (gulp!) and couldn’t eat meat on Fridays. The last rule, however, provided very good business for the local fishing fleet.

The more liberal and, for that time, “Bohemian,’’ folks attended the Unitarian Church – for which the joke motto was “the fatherhood of God, the brotherhood of man and the neighborhood of Boston.’’ The Unitarians removed as much as they could assertions about the divinity of Jesus from their hymns and liturgies. As the years passed, even references to God diminished. General, diffuse celebrations of the glories of nature and plugs for the Civil Rights Movement replaced them. The minister had the lovely name of the Rev. Roscoe Trueblood.

The Congregational (aka “Congo”) church in Cohasset was only vaguely Trinitarian. The Congos were more or less the direct descendants of the Puritans, the Unitarians less directly so.

There also was, and still is, a Hindu temple in town!

Back to the campaign motorcade. Some kids sang “Whistle while you work, Stevenson is a jerk,’’ of course a play on the song “Whistle While You Work,’’ from the Disney movie Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs, which all the children had seen.

It already seemed to me that politics was harsh.

Is it politically incorrect now to refer to “dwarfs’’?

The town and most of the rest of America went heavily for Dwight D. Eisenhower (1890-1969) over a former Democratic governor of Illinois, Adlai E. Stevenson (1900-1965). But the Republican Party was a very different creature from its current version, and Ike was a good, middle-of-the road president, supporting incremental improvements in federal domestic programs and warding off war. Both Eisenhower and Stevenson were notably dignified.

You can understand why a few years later, soon before his death, a very tired Stevenson, then U.S. ambassador to the U.N., would say that “All I really wanted was to sit in the shade with a glass of wine and watch the dancers.” I’m pretty sure that many of us, tired of the increasing toxicity and tumult of public life, would sometimes want to declare a separate peace and maybe flee, with no forwarding address, and certainly no social media, to some remote, Arcadian place. One thinks of the phrase “a separate peace’’ in Hemingway’s World War I novel A Farewell to Arms and John Knowles’s boarding-school novel, set in World War II, A Separate Peace.

In the Cohasset air was the aroma from piles of raked up (not blown!) leaves being burned – an activity now banned, mostly for public health reasons. Many of us of a certain age still miss that sweet smell, now replaced in too many neighborhoods by the aroma of gasoline from shrieking leaf blowers. Before their parents burned the leaves, small children loved to burrow into big piles of them.

Ah, youth! I remember with a pang the town’s scenic shores and the material comfort available to so many of its residents, along with dark scenes out of a Eugene O’Neill play.

Thoughts on summer as it ebbs (?)

“Summer Dreaming” (encaustic painting), by Nancy Whitcomb

(The trick is to get across the Cape Cod Canal bridges.)

Adapted from Robert Whitcomb’s “Digital Diary,’’ in GoLocal24.com

Like many GoLocal readers, I’ve spent much of my life near beaches. To me, they’ve mostly become places to simply walk on, especially in the off-season, to clear one’s head and maybe spot some interesting wildlife, dead or alive.

Where I lived during much of my youth, in Cohasset, on Massachusetts Bay, there’s a mix of sandy gray beaches and very uncomfortable stony strands (recalling Maine) and summertime water that, at least back then, was sometimes much too cold to comfortably swim in, especially on the hottest days, when the southwest wind blew the warm surface water seaward. I came to think that these beaches were mostly good for clambakes, fireworks and letting our dogs run on them. (No enforced leash laws in our town then.) All too often, bunker oil dumped from ships going into Boston Harbor (see below) would coat the beaches, which were also popular teen drinking places at night.

In West Falmouth, on Buzzards Bay, where our paternal grandparents lived, it was quite different, with the usual sou’wester pushing the 77-degree surface water (already fairly warm because of eddies from the Gulf Stream and the shallowness of the bay) toward the soft beach, which included a private club with a simple gray-shingled building that had to be rebuilt after major hurricanes and a tennis court that had to be frequently swept of the sand that blew in from the sand dunes that bordered it.

It had/has a swimming dock that was a centerpiece of kids’ activities there. (There were also some board games in the clubhouse for rainy days and some mildewed books, heavy on potboilers.) Do they worry about sharks swimming near the beach now? We never did.

I never much enjoyed sitting or lying on beaches, with the sand getting into your hair, eyes, swimming suit, sandwiches and potato salad. And no matter how much you rinsed your feet, the grains would stick in your sneakers and end up on the floor in the car and back home. And then there were the flying rats known as seagulls, which would swoop down and steal your lunch and maybe leave a deposit on your head. And sometimes, layers of biting-insect-luring seaweed would cover the lower beach.

Still, the sound of the waves was soporific and being able to look at a far horizon, with its many sailboats, helped put troubles into perspective. And there’s no doubt that being in the sun felt good (for a while), though at the risk of burns and skin cancer (which I’ve had plenty of). Few people thought about that more than 50 years ago. I remember my parents saying “You sure look healthy!’’ when looking at my red face.

The best part of that beach to me became the porch, where I’d read for hours sitting in a rocking chair and taking swigs of the Orange Crush I bought at the club’s little snack bar. There in the shade and a cooling breeze I’d enjoy the views and sounds of the beach without much of the mess, though on a gusty day sometimes sands would blow in there, too.

Does going to beaches tend to make people more environmentalist? We now occasionally use, for a modest annual fee, a beautiful beach, along a cattle farm and tidal river, in South Dartmouth, Mass. It has no facilities except a couple of Port-a-Johns, which, helpfully, tends to discourage day-long visits.

Most importantly, it’s set up in part as a nature preserve – the threatened Piping Plovers, etc. This role tends to make members talk about conservation a lot as they gaze at the low hills of the Elizabeth Islands across usually hazy Buzzards Bay.

Then there were the French beaches where, when we lived and worked in that nation, we were surprised/titillated by how much Western traditions governing public nudity have changed in some places and how waiters would bring food and drinks to you right onto the beach.

We found the most ominous beaches in Florida, with the poisonous Portuguese Man O’War with their lovely blue balloon sails that you wanted to pop, the certainty that there were indeed sharks off the beach commuting up the Gulf Stream, and the brown, wrinkled and irascible retirees. Worse, though mostly on the Gulf of Mexico side, were the toxic red tides, which polluted the air several blocks inland.

We always had small boats – rowboats, small sailboats, up to 17 feet long, even a canoe. We had an outboard motor or two to stick on sterns when needed, but these could be pesky to get going. The boats were practical possessions since we lived up a hill from a harbor. (The canoe was used on a nearby mill pond.)

Before fiberglass, the boats meant a lot of springtime work sanding and caulking the wooden bottoms before applying anti-fouling copper paint. Then we had to carefully maneuver a trailer to launch the sailboats in June and then reverse the process in late September. As the years rolled by, this got tedious.

The channel from the harbor out to the bay, which at Cohasset was really more the open ocean, was narrow, with ever shifting sandy shoals on one side and mussel beds (where we got our bait) on the other and sometimes was quite laborious to get through by sail.

In mid-summer heat waves you had to voyage out at least a mile, to the vicinity of the famous Minot’s Light, to get the real air-cooling effect. You’d hope that ships hadn’t recently dumped a lot of bunker oil, which could cover miles of water and give off a very noxious smell. Thank God for the EPA!

Then back to the small harbor, which became increasingly crowded with large and small pleasure boats over the years, I suppose because of growing local affluence as this small town became an all-out suburb. No longer were lobster and other commercial fishing boats numerous.

It was soothing to go sailing alone, which, if the breeze were a steady 10 to 20 knots, would put you in a ruminative mood. Sometimes you’d throw out an anchor and fish for mackerel, hoping that you wouldn’t get a dogfish instead.

It was also often fun to have small parties on the boats, except when the wind and social energy flagged and there you were – sometimes trapped for hours – in a small cockpit. Eventually, the claustrophobia might force you to use the outboard to motor in.

I still like to go out on boats once or twice a summer if I have a pretty good idea of when I’ll get back to shore. But with the expense and time involved in owning a boat, I’d just as soon have it someone else’s.

xxx

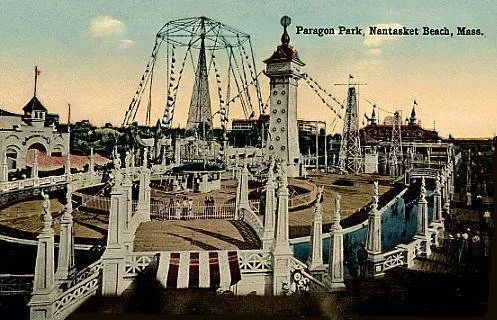

Paragon Park, in Hull, in 1914

There was a now long-gone amusement park, called Paragon Park, along a rather polluted strand called Nantasket Beach, in Hull, Mass., that we’d be taken to about once a year, often around my birthday. There was a lethal roller-coaster, a fun house with sloppily made monsters and, my favorite, something called “The Rotor.” This giant infernal cylindrical device, into which you’d walk, would spin you around at such velocity that you’d be stuck to the walls. (Sounds like astronaut training.)

Inevitably, a kid would get sick and upchuck the junk food (cotton candy, popcorn and hot dogs, etc., of indeterminate origin). Perhaps for the same reason that I very rarely get seasick, I didn’t suffer this misfortune.

Then there were the games (with prizes “Made in Japan,’’ back when that phrase meant cheap instead of high quality), which usually involved throwing a ball at something as a bored attendant (usually an older teen doing this as a summer job) looked on with a frown or a rictus smile.

Paragon Park was notably garish but, especially when you’re young, “kitsch is everything you really like,’’ in the immortal words of our late musician friend with the wonderful name of Page Farnsworth Grubb, who ended his years in Iowa. Despite what you might think from his name, he was about the least pretentious person you could meet. By the way, if you want pretentious, look at the marketing for “The Preserve,” in Richmond, R.I.

Flood voyeurism

Glades Road in a frequently flooded section of Minot, a neighborhood of Scituate, Mass. “The Glades” is a summer compound of Massachusetts’s historically famous Adams family. Hit the links below to see the area in a more exciting situation.

Adapted from Robert Whitcomb’s “Digital Diary,’’ in GoLocal24.com

When I was kid, we much enjoyed the coastal flooding that accompanied Nor’easters in Cohasset, my hometown on Massachusetts Bay. Sometimes the water would cover some stretches of streets from which you couldn’t see the ocean because of the woods in the way. Sometimes we’d get to row on these roads. Cheap thrills indeed.

But a better show was in nearby Scituate, where a densely packed community on a point, with both summer and year-round houses, is massively flooded every few years. The houses shouldn’t be there, but federal flood insurance, which started in 1968, sustains this seeming idiocy even as rising sea level makes places such as Scituate more vulnerable.

After I got my driver’s license, I’d go to Scituate alone or with friends to watch the show and take some pictures.

Hit these links to get a sense of what we’d see:

Those old small-town reports

The Cohasset Common still looks much as it did in the ‘50s except the elms are gone because of Dutch Elm Disease.

Still the venue of generally polite town meetings

— Photo by ToddC4176

From Robert Whitcomb’s “Digital Diary,’’ in GoLocal24.com

The other day I looked at municipal reports of my hometown, Cohasset, Mass., in the late ‘50s, when I lived there. There have been big changes since then, among them that Republicans outnumbered Democrats by more than 5 to 1, reflecting the old allegiances of small-town New England Yankees back then: The town’s Democratic now. And they called the town dump the “town dump’’ instead of the euphemism of Cohasset’s current “Recycling Transfer Station’’.

The old reports’ language was a bit more formal than now, indeed sort of Victorian, to wit, in the late ‘50s: “That the Selectmen are instructed to advise His Excellency the Governor and our Senators and Representatives….” And nicknames are frequently used now in the reports, a practice unheard of back then.

There were also such reminders of the passage of time as Memorial Day being called Decoration Day (in my house we still called Veterans Day Armistice Day back then) and a plan to spray a wetland with DDT, the environmental menace that wouldn’t be banned until 1972. But perhaps the most noticeable change was that most of the names of town officers in the reports in the late ‘50s were WASP, and now there are lots of Irish and Italian names, and some names whose ethnicity is hard to figure. Those once-city dwellers left the city to move to the suburbs, including now-rich ones such as Cohasset.

But I was charmed to read that the town still has that old colonial occupation of “fence viewers,’’ charged with dealing with property disputes.

You can learn a bit of local culture and sociology by reading old small-town reports.

Alone together

As upgrades made party-lines more popular in the 1940s, local telephone companies ran frequent ads to instill community spirit and personal courtesy in party-line subscribers.

From Robert Whitcomb’s “Digital Diary,’’ in GoLocal24.com

“Think how we spend our leisure time now compared to 10 years ago: alone with our Netflix, Instagram, Spotify. No wonder our mental health is eroding and we seem to hate everyone else.’’

-- Gerard Baker in his Dec. 20-21 essay in The Wall Street Journal, “Farewell to the 2010s, the Uneasy Decade of Populism’’

A few years ago, we had a nice family to lunch. They’re a very internationalized crew. Anyway, what struck me in almost comic form was that they were spending much of the meal on their new smart phones, making global travel plans and otherwise communicating with the wide world. (The very ugly table around which we sat, by the way, has quite a history: It was made in a French military prison in Lebanon in the 1920s. My wife bought it off the daughter of the French army officer in charge of the prison.)

I thought of that meal the other day when I came upon a story in The Atlantic magazine about land line phones. Before smart phones, most households had one or at the most two phones. Families had to share them, and the phones were generally in such public places as the living room, the kitchen or the front hall. So there was much less privacy than with cell phones and so more communal family knowledge. Now, phones tend to keep us separated. But then, this is part of a broader tendency to eschew physical person-to person communication in favor of communication via screens. By making it easier to avoid having to become habituated to real, face-to-face contact, these digital devices seem to lead to more and more people being anxious when, for instance, being interviewed in person (not on Skype!) for jobs. HR people tell me that some young job applicants avoid looking at their interviewers in the eyes.

I’m old enough to remember when small towns (including the one I lived in, Cohasset, Mass.) had “party lines’’ that enabled operators of what was called “The Phone Company” (a tightly regulated monopoly) to monitor phone calls and do such things as telling pranksters (usually kids) to hang up, or to call an ambulance. It was truly a community service. It wasn’t always a very efficient system but it could be pretty entertaining, and some family disasters were averted through the heroic efforts of operators at their switchboards.=

A cousin of this phenomenon is the dearth of working people taking the time (or being allowed to take the time) to go to lunch with workmates and others; rather, they eat their lunches at their desk. Thus another opportunity for maintaining social skills falls by the wayside.

Maybe a nice New Year’s Day resolution would have been to spend a bit more time with people in the flesh. But cellphones and computers are engineered to be addictive….

To read the article in The Atlantic, please hit this link.

Molecules in the sun

The cement pond on the Cohasset, Mass., common.

“I lay on the lush green of the Commons watching you traipse through

the knee-deep

water of a cement pond, splashing and kicking

each molecule of water momentarily suspended….’’

— From “Many Little Suns,’’ by Renuka Raghavan

The weight of history in 'Manchester-by-the-Sea'

The Old Burial Ground in Manchester-by-the-Sea, Mass. (Photo by John Phelan)

Adapted from Robert Whitcomb’s “Digital Diary’’ in GoLocal24.com

Some readers may have seen the recently released movie Manchester-by-the-Sea, a devastating family tragedy, but with comic moments, too, and all suffused with a haunting New England atmosphere. I have seen few movies that present a sharper view of the often bleak beauty of New England’s coast and towns or of the anxieties and occasional joys of America’s lower-middle class, New England sub-species.

The film is mostly set in the eponymous Massachusetts town on Greater Boston’s North Shore.

While the official name is the same as in the movie, when I was growing up in Cohasset, across Massachusetts Bay from the town, we only called it “Manchester.’’ I mostly remember the capacious gray-shingled summer places along the town’s rocky headlands and the big Federal Style and Greek Revival houses inland a bit. \

Many of the grandest places in Greater Boston are on the North Shore. That’s where a lot of Boston Brahmins repaired to in the summer; some moved there year-round after they winterized their summer places (when they weren’t in Aiken, S.C., Palm Beach, etc., in the winter). Perhaps because the North Shore ports of Salem and Newburyport had many of the China Trade types who became Boston’s aristocracy, it denizens tended to look down on the South Shore, although Cohasset and Duxbury had/have certain old-money pretensions. So there were social links between the two shores, such as annual sailsbetween the Cohasset and Manchester Yacht Clubs. But someone from Cohasset approaching the shore of Manchester quickly knows he/she is entering more-monied waters than those back home .

The South Shore’s mostly sandy and shallow harbors, as opposed to the deeper rock-rimmed ones north of Boston, made them unattractive for ocean-going ships in the China Trade. Instead, the local big money often came from the shoe business and such things as rope-making. Not as romantic as trading with China!

Manchester has economically struggling people too, and the movie is mostly about them. Like many, perhaps most Americans now, they are downwardly mobile. Too many of them medicate their anxieties, which can move into despair, with booze, opiates and cocaine.

Thoreau wrote that “The mass of men lead lives of quiet desperation’’. The characters in Manchester-by-the Sea are not always quiet but they are usually stoical in their suffering from their own mistakes and others’ outrages inflicted on them. But they can still summon up some dark comedy and savor the absurd.

As the movie’s characters walk or drive through Manchester and neighboring towns, you get a sense of the weight of the region’s long history and of the cheeriness of its sunny days alternating with the gloom of its cold, gray and mean winter days darkened by proximity to a hostile ocean. Toward the end of the movie, you even get a sense of the uplift from winter finally succumbing to spring, when the ground has thawed out enough to permit the burial of one of the movie’s characters.

The movie obliquely recalls the regional history that pressed in on Nathaniel Hawthorne (from Salem) in The House of Seven Gables and The Scarlet Letter and William Faulkner’s line “The past is never dead. It’s not even past.” New England and the South have a heavy thing on common: the weight of the most complicated histories of any American region except, perhaps, New York City.

One thinks of Faulkner’s novel Absalom, Absalom! in which the Harvard roommate of the Mississippian Quentin Compson says: : “Tell about the South. What's it like there? What do they do there? Why do they live there? Why do they live at all?" You might ask the same question in mid-winter of New Englanders.

In Manchester-by-the Sea, the pertinent past is mostly in the lifetime of the main characters but you can feel the pressure of earlier time, too. And the film might remind us that most of those we encounter have potent psychic pain we know nothing about. If we did, we might pay attention to the old line: “To understand all is to forgive all,’’ though empathy can sometimes be over-rated.

The tort museum and other N.E. small-town thrills

Inside the American Museum of Tort Law, in an old bank building in Winsted, Conn.

From Robert Whitcomb's Nov. 3 "Digital Diary'' column in GoLocal24.

In Winsted, Conn., there’s a new temple to one of America’s best known characteristics – its litigiousness. In that small city in the Litchfield Hills, famous consumer litigator Ralph Nader has founded the American Museum of Tort Law, which involves cases of wrongful injury. Winsted is Mr. Nader's hometown and he has been very loyal to it.

In the museum are such exhibits as the dangerous Chevrolet Corvair, which Mr. Nader helped drive off the road (see his book Unsafe at Any Speed), unsafe toys and the Dalkon Shield IUD.

The museum shows how tort law evolved within English Common Law and American law up to the present, including (to me) such silly cases as that brought against McDonald’s after someone scalded herself with its hot coffee. And the plan is to build a replica of a courtroom.

As the pyramids were tributes to pharaohs, so the museum, in a beautiful old bank building, will be to the 82-year-old Mr. Nader.

By the way, Winsted, a small former factory city in the Litchfield Hills, is famous for having the buildings on one side of its Main Street swept away in 1955 by the surging Mad River in torrential rains produced by Hurricane Diane, giving the downtown a slightly surreal quality, which the tort museum will intensify.

xxx

In other Nutmeg State news, 1,300 fans of a TV show called Gilmore Girls last month descended on the town of Washington, which is supposed to have inspired the improbably quaint and pretty town called “Stars Hollow’’ in the show. Steven Kurutz, of The New York Times, noted: {T}hey {the fans} wanted to do the impossible: to experience in a waking life a dream town built on a studio backlot.’’

I know Washington, Conn., having gone to school in nearby Watertown, Conn. It’s very pretty, but of course not nearly as Norman Rockwellian as the TV show. Will the new publicity about Washington cause it to be overrun for a long stretch to come? No. There are even prettier towns in Connecticut.

The story reminded me of the invasion of Cohasset, Mass., on the ocean about 45 minutes east southeast of Boston, when some of the movie The Witches of Eastwick, based on the eponymous Updike novel, was shot in the ’80s after the folks in the also lovely town of Little Compton, R.I., decided that they didn’t want a Hollywood invasion. I grew up in Cohasset and can testify that there was a full quota of bad and sad behavior there by the then Greatest Generation’s young to middle aged adults – adultery, alcoholism, suicide. The cuteness of Cohasset wasn’t enough to ward off evil spirits. It’sa good place for witches.

Finally, the Gilmore Girls case reminds me of how nice Providence looked in the NBC show of the same name back in the ‘90s. Indeed, virtually perfect.

My wife and I have a friend, Vicki Mercer, M.D., a pediatrician and former TV scriptwriter who was the adviser on medicine for the show, which revolved around a young and attractive female doctor prospering in the “Providence Renaissance’’. Vicki took us to the studio in Los Angeles where the interior scenes, including of the physician’s house, were shot. Somewhat eerily, I discovered that the outside shot of the doctor’s house was of the house of a late aunt and uncle of mine on the East Side of Providence.

The show would have been more interesting if it had included more scenes of the tougher aspects of Providence but the producers were, after all, pushing escapism, not education.

Village to summer place to rich suburb

"Surf, Cohasset {Mass.}, by MAURICE PRENDERGAST, painted around 1900, by which time the small town -- really a village -- had become a much-loved summer place for the affluent of nearby Boston and the shoe-manufacturing area in and around Brockton to the south. The Old Colony Railroad made it very easy to get to.

"Surf, Cohasset {Mass.}, by MAURICE PRENDERGAST, painted around 1900, by which time the small town -- really a village -- had become a much-loved summer place for the affluent of nearby Boston and the shoe-manufacturing area in and around Brockton to the south. The Old Colony Railroad made it very easy to get to.

It has a rather famous drive on Jerusalem Road along the top of low bluffs overlooking Massachusetts Bay. That road becomes Atlantic Avenue, which ends at the town's beautiful if overcrowded harbor, dominated by a mansion that used to be owned by the family that controlled Dow Jones & Co.

The main drawback of Cohasset as a summer place is that the water is quite cold -- struggling to get to the mid 60s in the middle of summer -- and so is uninviting to swim in. And, of course, real estate is astronomically expensive. It has become one of America's richest suburbs.

The trains disappeared after the late '50's for decades, but now are back. The Fidelity and bio-tech executives can thus pleasantly read their copies of Barron's to and from work in downtown Boston.