In a beautiful but sometimes grim region

“Pears,’’ by Audrey Shachnow, in the show’”, through Oct. 20, “Sculpture at The Mount’,’ the former (mostly) summer estate, in Lenox, Mass., in the Berkshires, of Pulitzer Prize-winning novelist Edith Wharton (1862-1937). Ms. Wharton wrote a grim classic novel titled Ethan Frome about characters in the Berkshires.

The Mount staff says:

“‘Sculpture at The Mount’ showcases a diverse range of sculptures of varying scale and media produced by emerging and internationally established artists. This immersion of art in the natural world is free and open for the public to explore.’’

Don Pesci: An apolitical and literary jaunt in The Berkshires

A view of the Mt. Greylock Range from South Williamstown (from the west). The Hopper, a cirque, is centered below the summit.

—Photo by Ericshawwhite

Arrowhead, where Herman Melville wrote Moby Dick.

Lee, Mass., in The Berkshires, is everyone’s vision of a typical New England town. The Main Street is short and to the point. Buildings, unmolested by town planners, have maintained their character throughout the years. The house where we bunked for several days dates from the 19th Century and has been well kept by its owner, an engineer who had, like Odysseus, moved about in the world. He was born, very likely in or near the house we occupied, moved with his family to Washington, D.C., where his father had found a job that he could not refuse as an electrical engineer, and later back to Lee.

The firehouse across the street from Garfield House, where we stayed, is a solid stone structure that boasts a square steeple that one easily might mistake for a bell tower or a medieval watch tower.

Traveling around New England, one must – delicately, delicately – approach the topic of politics. Open wounds are everywhere. Much of New England is solid ultramarine blue (there are dramatic exceptions, such as Aroostook County, Maine). That is to say that many people in New England wish to see former Donald Trump in leg irons waltzing through a prison yard. My wife, Andrée, believes that such emotions are far too enthusiastic. She taught American Studies for many years and is intimately familiar with the religious enthusiasms of the 17th Century that saw a witch behind every bush.

Trump, she likes to say when not in the presence of people still suffering political whiplash from the 2016 Hillary Clinton/Donald Trump campaign, is, in some respects, a man more sinned against than sinning, though, of course, she would never say such things in the presence of those who wish to burn Trump at the stake – which is to say, in a good deal of New England. Consider that Democrats in Connecticut, a part of New England and our home state, outnumber Republicans by a two-to-one margin, with unaffiliateds topping Democrats by a small number.

Andrée laid down the law long ago: There will be no politics spoiling our vacations. This law of the household precedes Trump’s ascendency to the presidency by, say, a half century or more. No politics means no computers, no cell phones, no newspapers, no furtive notes written in the shadows, and only mercifully brief encounters with witch-burners.

“Just change the subject, will you?”

In very few places throughout the world -- Washington, D.C., of course, other uncivilized places that used to be part of the British Empire, including most of New England, and Italy— everywhere and always – political talk with strangers destroys the moment, and living in the moment is essential to travel. In Florence, Italy, we almost missed, through dreamy inattention, the spot where Savonarola had been burned at the stake. It is a grave sin to have eyes and not see, ears and not hear, when traveling about the world.

Just ask Odysseus, a victim of enchantment and forgetfulness during the year he spent, not unpleasantly, with Circe. First, the traveler forgets where he is, then who he is, and then the once-solid world dissolves like a dream.

“Pay attention!”

It was no chore for us to pay attention to Herman Melville, most famous, of course, as the author of Moby Dick. In college, he was our literary touchstone. One day, early in our marriage, I brought home a little-read book by Melville, Pierre or the Ambiguities. It’s a romance novel, and Andrée, an incurable romantic, fell for it head over heels. A little later, though we already had been married a couple of years, she fell for me, not quite head over heels.

We had visited Arrowhead, Melville’s home in Pittsfield, years earlier when the house was in transition. No one was home, the house, garnet-red at the time, was dark and forbidding and vacant. Even the spirit of the place had taken flight. We peeked in the windows. Off in the background, Mt. Greylock, the highest elevation in Massachusetts, showed his hump.

Melville wrote Moby Dick in this house. He dedicated the book to his good friend Nathaniel Hawthorne, then living part time in nearby Lenox. The book following Moby Dick, Pierre or the Ambiguities, was dedicated as follows: “'To Greylock's Most Excellent Majesty ... the majestic mountain, Greylock — my own more immediate sovereign lord and king — hath now, for innumerable ages, been the one grand dedicatee of the earliest rays of all the Berkshire mornings, I know not how his Imperial Purple Majesty ... will receive the dedication of my own poor solitary ray ...''

Greylock, we found, was full of winding ways, but so was Melville’s route through a tortuous world. Moby Dick, now considered a classic American novel, was a conspicuous failure in its day. And it was only after Melville had died that the book rose from its deadening reviews.

Today, as always, the book must be read aloud, not so much with the eye as with the ear of the heart. It is music to the ear and, like all music, it winds its way over long Shakespearian passages, moving gracefully at its own pace. It was this music that had enchanted Andrée so many years ago.

The trip to Arrowhead reminded me that traveling is an inward experience, not merely a collection of interesting photos taken of interesting places along the way.

Mark Twain, a Connecticut resident for many years, traveled widely in Europe. And partly on the basis of that, he wrote a little-read book he considered his best: “I like Joan of Arc best of all my books… It furnished me seven times the pleasure afforded me by any of the others; twelve years of preparation, and two years of writing. The others needed no preparation and got none.” (The full name of the novel is Personal Recollections of Joan of Arc.)

Twain was anti-clerical, not necessarily anti-religious. But the character of Joan, buried for many years under heaps of anti-Catholic perfidy, was paramount for Twain: “Taking into account…all the circumstances—her origin, youth, sex, illiteracy, early environment, and the obstructing conditions under which she exploited her high gifts and made her conquests in the field and before the courts that tried her for her life—she is easily and by far the most extraordinary person the human race has ever produced.”

The Mount, novelist Edith Wharton’s plush estate in Lenox, is only a 10-minute ride from Garfield House.

There’s a picture on one wall in the estate’s mansion of a salon gathering in which Henry James makes an appearance. Anything Jamesian is redemptive for Andrée. As an American Studies and American Literature teacher for many years, both in Catholic and public schools, she taught James and other famed authors to students who eventually came to appreciate James’s long winding prose paths – very Shakespearian and even Melvillean.

Twain was not a James fancier: “Once you put him down, you can’t pick him up again.”

But Andrée likes the winding ways of a strong – dare I say it? -- Faulknerian sentence, very much like the path the imagination takes when it is called into service in our travels.

Our next-door neighbor at Garfield House, a permanent resident and an expat from New York, told us that she had lived for a time in Wharton’s reading room while she was an administrator of the Shakespearian Company that put on plays at The Mount.

“You were an actress?”

“Oh, God no, please no – not an actress. I worked behind the scenes as an administrator to put on the plays.”

“In New York?”

“Yes. New York had become too cloying, so I came here, fell in love with the place and stayed. By the way, you told me that you like golf, but you do not like golfers. Just a word to the wise: You had better not say that to the proprietor of Garfield House, who is an avid golfer.”

I agreed, as Andrée said, to “change to subject” if it came round to golf.

Golf, like politics in New England, has become in recent days a secular religion full of saints and heretics – none of them, unfortunately, quite like St. Joan of Arc.

Twain on politics: “In religion and politics people’s beliefs and convictions are in almost every case gotten at second-hand, and without examination, from authorities who have not themselves examined the questions at issue but have taken them at second-hand from other non-examiners, whose opinions about them were not worth a brass farthing.”

Now there, Andrée might say, is a near perfect Jamseian sentence, very much like the hiker’s paths that cross and re-cross Mount Greylock. Our very last adventure before leaving Lee for home was to ride – not walk – to the top of Melville’s “sovereign lord and king.”

Don Pesci is a Vernon, Conn., based columnist.

Front Entrance of The Mount.

— Photo by Margaret Helminska

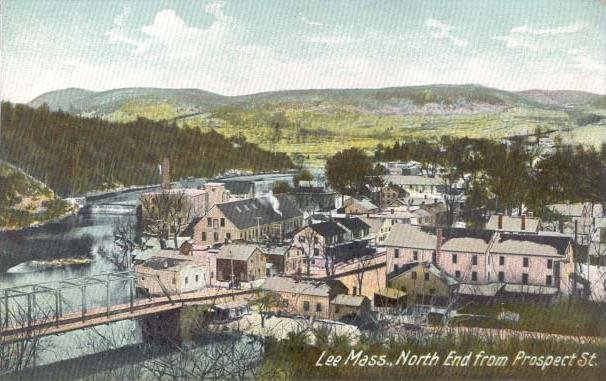

1907 postcard.

Berkshires bathos

Sweet-fern

“Even the abundant enumeration of sweet-fern, asters and mountain-laurel, and the conscientious reproduction of the vernacular, left me with the feeling that the outcropping granite had in both cases been overlooked. I give the impression merely as a personal one; it accounts for Ethan Frome, and may, to some readers, in a measure justify it.’’

Novelist Edith Wharton (1862-1937), who had a summer estate in The Berkshires, in her introduction to her tragic novel Ethan Frome (1911), which is set in that region.

Vista overlooking The Berkshires from the New York State border at sunset

— Photo by BenFrantzDale~commonswiki

Have to settle for where we are

The Mount, Edith Wharton’s country place, in Lenox, Mass., in The Berkshires. from when its construction was completed, in 1902, to when she left to live in France in 1911. It’s now a museum. Ms. Wharton knew the sad and impoverished aspects of The Berkshires, too, as you see her novella Ethan Frome.

“It was easy enough to despise the world, but decidedly difficult to find any other habitable region.

— Edith Wharton (1862-1937), American novelist.

A town in The Berkshires in 1884

Mining the real rural New England

The Mount, the (mostly)summer mansion built for Edith Wharton in 2002 in Lenox, Mass., in the Berkshires.

"I had known something of New England village life long before I made my home in the same county {Berkshire County, Mass.} as my imaginary Starkfield; though, during the years spent there, certain of its aspects became much more familiar to me. Even before that final initiation, however, I had had an uneasy sense that the New England of fiction bore little -- except a vague botanical and dialectical -- resemblance to the harsh and beautiful land as I had seen it. Even the abundant enumeration of sweet-fern, asters and mountain-laurel, and the conscientious reproduction of the vernacular, left me with the feeling that the outcropping granite had in both cases been overlooked. I give the impression merely as a personal one; it accounts for Ethan Frome, and may, to some readers, in a measure justify it.''

-- Introduction to the novel Ethan Frome, by Edith Wharton