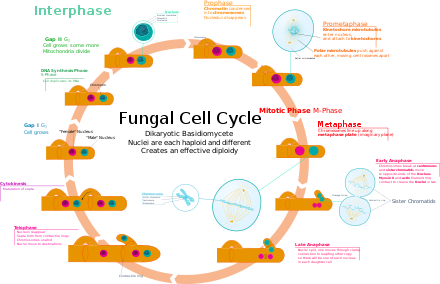

Fungi festival

Fungus vs. tree stump

Text from Colleen Cronin for ecoRI News

AUKE UT NAHIGANSECK/CHARLESTOWN, R.I. — While mycologist Lawrence Millman waited for his ride to the 24th Annual Rhode Island BioBlitz from the Providence Train Station, he did something he rarely does: he used his cellphone to call the reporter who was supposed to pick him up.

Millman only bought a cellphone two years ago, but often refuses to use it and rarely gives out his phone number. He usually arranges things via email, including rides, because he doesn’t own a car and let his driver’s license lapse years ago.

For the Rhode Island Natural History Survey’s annual BioBlitz, which he comes down from his home in Cambridge, Mass., to attend annually, he wore an old T-shirt aptly screen printed with mushrooms, hiking boots, and a bit of gray scruff.

He has been coming to the event — a 24-hour scramble to survey the number of species at a particular Rhode Island site — for a decade, he thinks. It’s one of the only mycological events that he still likes attending.

“Male myco-files of a certain age are very eager to compete with each other,” Millman said.

The fungi enthusiast doesn’t like crowds and doesn’t much care for the norms and rules of life, much like the numerous but elusive organisms he likes to study.

To read the whole article, please hit this link.

Art, not anguish

“Teardrop (After Robert Irwin)” (polished stainless steel with mirror finished, halogen lighting), by Pakistani-American artist Anila Quayyum Agha, in the group show “Tradition Interrupted,” at the Lamont Gallery, at Phillips Exeter Academy, Exeter, N.H., through Dec. 10.

— Courtesy of Talley Dunn Gallery, in Dallas

The gallery says that each artist in this exhibition was tasked to "weave contemporary ideas with traditional art and craft," with the aim of bringing experiences of their cultures and marrying them to different mediums that complement each other.

‘We are still here’

The cairn in question.

Adapted from Robert Whitcomb’s “Digital Diary,’’ in GoLocal24.com

I wrote too whimsically in an Oct. 23 column that I had come across this cairn while walking on the lawn at the Roger Williams National Memorial, in downtown Providence, and asked what it is. Here’s the answer from the National Park Service, via my friend Ken Williamson, who lives in Hawaii.

“This cairn, or stone pile, depicts pieces of Narragansett {Tribal Nation}

history from pre-contact {with Europeans} through today. Built by Narragansett artists associated with the Tomaquag Museum {in Exeter, R.I.} it expresses the fact that WE ARE STILL HERE. The cairn is at the center with 4 raised stones around it representing the Four Directions. It is a meditative circle, representing Narragansett lives, history, and future which brings us full circle. Sit down and reflect on your own past, present and future and its intersection with the Narragansett people.

“The Narragansett Tribal Nation has lived on these lands since time immemorial. Their ancestors respected all living things and gave thanks to the Creator for the gifts bestowed on them, as do Narragansett people of today. Lynsea Montanari & Robin Spears III, both Narragansett, served as summer arts interns at the memorial for this project. They incorporated their own cultural knowledge with teachings by tribal elders regarding first contact with European settlers, genocide, displacement, assimilative practices, enslavement, continuation of language, ceremony, and other cultural practices. The artists chose to create a cairn as it is a part of the history of all indigenous peoples. There are many historic cairns in the Narragansett landscape.’’

xxx

My strongest memory of Native American cairns comes from driving with my wife in the forests along the northern side of gorgeous Georgian Bay in Ontario. You can’t go far there without seeing a cairn or other stone sculpture on a slope above the road.

Tomaquag Museum, in the Arcadia section of Exeter, R.I.

—Photo by John Phelan

Confident and vulnerable in Trumpian orange

“Self” (mixed media), by Laura Harper Lake, in her show “Vivid and Vulnerable Vessels,’’ at Foundation Art Space, , N.H., June 3 through June 25.

She says: “The human form can receive varying reactions when a person views themselves with a self-assessing mind. At times we may be confident, much like the bold, vivid colors on my canvases, which are all wood. In other moments, we may feel like the thin layer of iridescent paint I use; vulnerable, exposing the natural grain beneath, and hesitant. I am a pendulum, swinging between these two radically different states of being.”

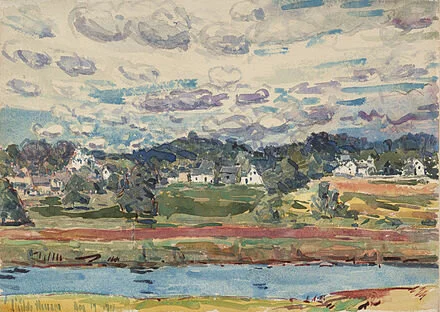

Exeter’s Squamscott Falls in 1907. The town has long hosted manufacturing enterprises, much of them originally powered by water power, but it’s best known as the home of Phillips Exeter Academy, the prep school.

‘It’s not intellectual’

Rock of Ages granite quarry in Graniteville, Vt.

]

“Never confuse faith, or belief — of any kind — with something even remotely intellectual.’’

— From A Prayer for Owen Meany, a novel by John Irving (born 1942)

The plot centers around John Wheelwright and Owen Meany, who live in the fictional town of Gravesend, N.H. (based on Irving’s hometown of Exeter, N.H.). As boys they are close friends, although John comes from an old rich family — as the illegitimate son of Tabitha Wheelwright — and Owen is the only child of a working-class granite quarryman. John's earliest memories of Owen involve lifting him up in the air, easy because of his permanently small stature, to make him speak. And an underdeveloped larynx causes Owen to speak in a high-pitched voice. During his life, Owen comes to believe that he is "God's instrument".

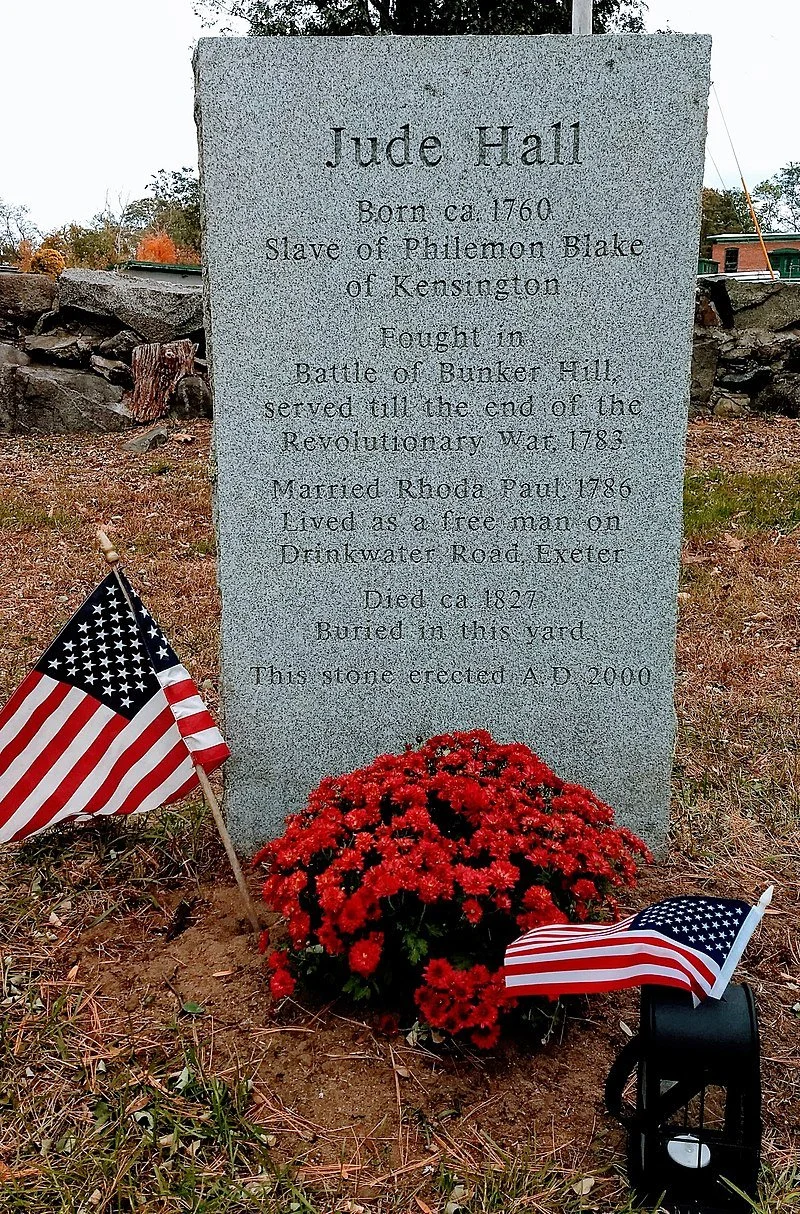

Jude Hall granite memorial stone in Exeter, N.H.

Brian P.D. Hannon: Of solar power and lots of tomatoes

Young tomato plants for transplanting in an industrial-sized greenhouse.

- Photo by Goldlocki

From ecoRI News (ecori.org)

National Grid has offered incentives to a company proposing to build a massive farm facility in rural Exeter, R.I., in exchange for access to the solar power expected to help grow millions of tomatoes in temperature-controlled greenhouses.

A June 24 letter from National Grid senior counsel Andrew Marcaccio to Luly Massaro, a division clerk for the Rhode Island Division of Public Utilities and Carriers, states National Grid will offer “energy efficiency incentives” to Rhode Island Grows LLC “for the utilization of a combined heat and power project with a net output of one megawatt ... or greater.”

A capacity of 1 megawatt or more is a utility-scale installation for solar power.

National Grid asks the public utilities and carriers division to follow an authorized process for combined heat and power (CHP) projects by reviewing materials submitted with the letter, including a purchase-and-sales agreement from Rhode Island Grows related to the project, an estimated budget, benefit cost analysis and a November 2020 analysis providing “well-supported justification explaining why the economic benefits are reasonably likely to be obtained.”

The letter’s attachments also include a report on the natural-gas requirements and local impact of the operation.

“These documents represent a report including a natural gas capacity analysis that addresses the impact of the CHP Project on gas reliability; the potential cost of any necessary incremental gas capacity and distribution system reinforcements; and the possible acceleration of the date by which new pipeline capacity would be needed for the relevant area,” according to the letter.

National Grid’s letter asked the public utilities and carriers division to review the materials and provide an opinion either supporting or opposing the proposal by Aug. 13.

Gail Mastrati, assistant to the director of the Rhode Island Department of Environmental Management (DEM), supplied a link tracking the progress of the wetland permit sought by Richard Schartner, owner of the Schartner Farms property where Rhode Island Grows plans to build a 1-million-square-foot closed facility.

Asked if Rhode Island Grows is required to file separate permit applications for a solar array capable of producing more than 1 megawatts of power, Mastrati said the wetland and stormwater permit “is based on the size of the solar arrays, not the power output. If the number of solar panels were to increase, a new or modified permit would be required.”

“DEM does not permit the power output, just the size of the facility as indicated on the site plans,” Mastrati wrote in an email.

Mastrati declined to reveal the name of the company providing solar array services to Rhode Island Grows.

“DEM does not get involved with the choosing of the company to perform the work,” she said. “It is up to the owner to ensure that the contractor completes the work according to the permit.”

Rhode Island Grows chairman Tim Schartner and chief financial officer Frederick Laist did not respond to a request for comment.

The Rhode Island Grows project has drawn the support of Ken Ayars, chief of the Rhode Island Department of Environmental Management’s Division of Agriculture, as well as criticism from some Exeter residents concerned about the environmental and cultural impact of the massive growing operation that would use high-tech greenhouses to grow millions of tomatoes for distribution in six states throughout the Northeast.

Rhode Island Grows proposes to use a technology called controlled environment agriculture. The automated, hydroponic system can produce food on a large scale and has resulted in extensive agricultural production in the Netherlands, according to a video on the Rhode Island Grows website.

The company projects the operation could yield 650,000 pounds of tomatoes per acre, with an expansion to 350 acres in five years and eventually to 1,000 total acres, with five employees per acre.

The Exeter Town Council voted June 7 to return the Rhode Island Grows proposal for a zoning overlay district to the Planning Board for further consideration. The overlay would allow construction of the industrial-scale operation on the Schartner Farms property off South County Trail, where Rhode Island Grows prematurely broke ground June 1.

The five members of the council did not respond to a request for comment on the National Grid letter.

Brian P.D. Hanlon is an ecoRI News journalist.

Go back where you came from

Junction signage in Newfields, N.H., as seen in 2005 (left) and 2019. It’s a beautiful small town to find yourself in, even if you’re lost. See below.

"We don't enjoy giving directions in New Hampshire. We tend to think if you don't know where you're going, you don't belong where you are."

— John Irving (born 1942), novelist who was born and raised in Exeter, N.H.

Squamscott Street in Newfields

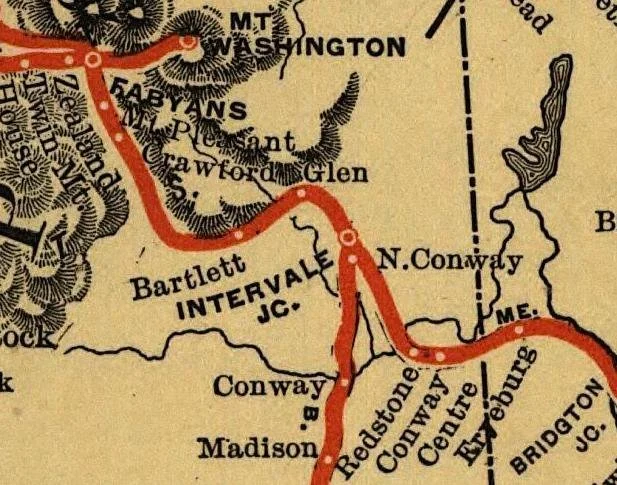

“Newfields, New Hampshire ‘‘(1917), by Childe Hassam, at the Princeton University Art Museum

'Materializing the medium's memory'

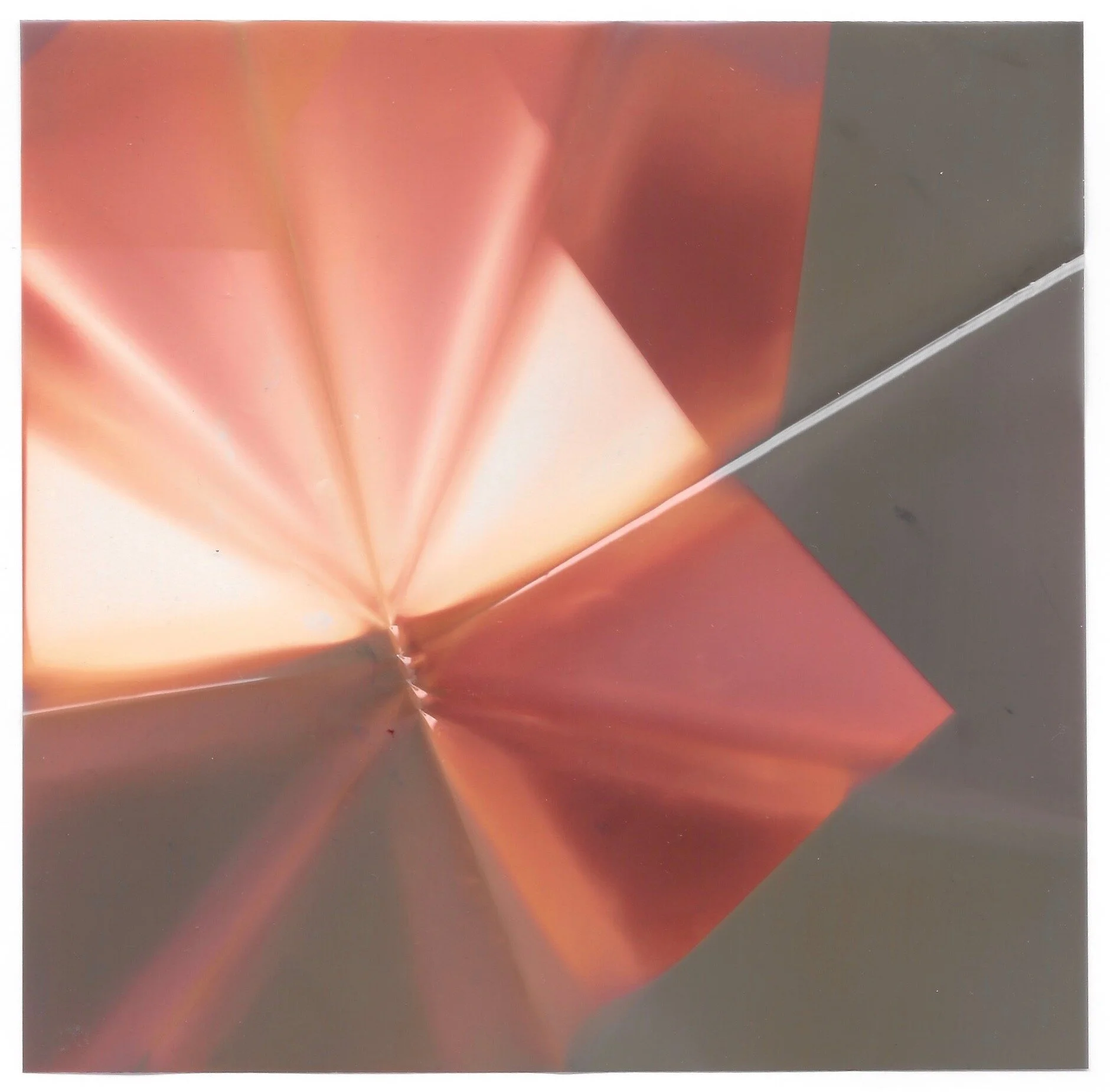

Image from ‘‘LUCID,’’ artist Exeter, N.H.-based Shaina Gates’s show from April 15 to May 15 at Gallery 263, Cambridge

The gallery says:

“This exhibition reflects the artist’s interest in the transfer and translation of images across surfaces, systematized processes, and theories related to dimensionality and the organization of space. In ‘LUCID,’’ a body of lumen prints on both paper and film are on view. The works in ‘LUCID’, which conjure a joy similar to what one may experience when looking through a kaleidoscope, map the physical experience of how the prints were systematically folded by the artist, materializing the medium’s memory as a visible record. In this way, the material becomes lucid.’’

Downtown Exeter, N.H.

Grace Kelly: Getting more Black and Brown kids out into nature

A meeting in the woods of Exeter, R.I., of students in the Movement Education Outdoors program.

— Photo by Grace Kelly for ecoRI News

EXETER, R.I.

A group of five 10th-graders tromp through a wooded path at the Canonicus Camp & Conference Center on Exeter Road. They talk about school, the platform Doc Martens they would love to have, and how New York Congresswoman Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez is great but also, it’s probably better not to idolize politicians. {Canonicus was a 17th Century Narragansett Indian chief.}

Their guide on this excursion is Joann “Jo” Ayuso, founder of Movement Education Outdoors (MEO), an organization with a mission to provide outdoor experiences for community-based organizations serving Black, Indigenous, People of Color (BIPOC) youth. She shows them nature.

“The outdoors is sacred, and yes, this land,” she said, and spreads her arms around her, gesturing at the grass and trees, “has a history of colonization, but I want us to feel welcome here. I want to invite you to make your own memories today, to decolonize this space. I introduce you to these spaces so you can own them and feel connected to the land.”

According to the National Health Foundation, while people of color make up nearly 40 percent of the population, 70 percent of the people who visit national forests, parks, and wildlife refuges are White. A mere 7 percent of national park visitors are Black.

There are many factors at play when it comes to communities of color not having the same opportunities to experience the outdoors. Ayuso said:

“I think it’s very important for people to know, that, for example, when your mom is a single parent, working three jobs, doesn’t have a car, how is she going to have time to take her kids hiking? And, unfortunately, bus lines don’t take you to any of the green space Rhode Island has to offer.”

There’s also the fact that outdoor gear is expensive, with basic equipment such as lightweight coats, hiking boots, and backpacks costing a premium.

“Equipment is always a barrier for young, low-income and urban youth,” Ayuso said. “Even having the proper layering for hiking in the fall or winter, that’s expensive.”

By starting MEO in 2018, Ayuso hopes to change this paradigm.

Ayuso’s journey from being born into poverty to being an outdoor educator for BIPOC youth started in the forests of the southern wild.

“One of my very first experiences with the outdoors was in the military,” she said. Ayuso entered the military after graduating from Joseph P. Keefe Technical High School, in Framingham, Mass., prompted in part by her brother who had also joined, and by the desire to work her way up in the world. While military service didn’t prove to be her dream, it was how she discovered her love of nature.

“One of the things I loved about the military was being outdoors, just hiking, having my rucksack on and just hiking for hours,” said Ayuso, who served in the Army in 1989-1996. “To this day, I can still remember smelling the eucalyptus trees in the South, and also smelling the pine trees when we would do our training early in the morning. It was just something that really helped me pass time, and that was one of the most memorable times of me experiencing the outdoors.”

Ayuso would come back to that moment years later, and it would be part of a series of experiences that would inspire her to create an organization to bring Black and Brown youth into nature.

In the years that filled her life between the military and MEO, Ayuso built a personal-training business in Wellesley, Mass., and left it, started a new life in Providence, learned she loved working with young people, began practicing mindfulness, and discovered her ancestral roots in Puerto Rico and West Africa.

But it was when she was hit by a car two years ago outside her Providence home and spent six months healing that she started to unravel what she wanted to do with her life.

“I had six weeks of recovery, and in those six weeks I was like, ‘I’ve gotta do something different,’” said the 48-year-old. “My partner and I just got to talking about what is it that you want to do for the rest of your life? What is it that you think you will enjoy?”

Her partner asked her to reflect on the past 15 years and think about the things she really loved.

“And I thought, ‘Damn, I really loved that time in the military when I was hiking. That was awesome.’ I felt like that was healing, that kept my mind kind of straight,” Ayuso recalled. “So my hiking experience in the military, the mindfulness training that I’ve had in the last 20 years, the Native and Black history I learned for myself, and seeing the environmental justice and climate change on Black and Brown bodies, that became the four pillars of Movement Education Outdoors.”

MEO partners with local schools such as Nowell Leadership Academy, in Providence, and such nonprofits as Riverzedge Arts, in Woonsocket, to bring underserved youth into the outdoors and to help them reflect on who they are and where they come from.

And on this chilly fall day in Exeter, the students are loving it.

As they walk through the forest of pine, oak and maple, they notice the acorns on the ground, the oak apple wasp galls tucked between fallen leaves, and learn about how beavers change the landscape to suit their needs.

They pause for a guided meditation at a bridge overlooking a pond and breathe in the cold air, watching as their breath billows around them when they exhale. They continue through the woods and stop at a rock wall to discuss the farming history of this land.

“So when the glaciers melted, they left lots of rocks here,” said a MEO intern. “And the colonizers used them to make rocks walls.”

Ayuso noted that these rock walls delineated farming property, and that between 1636 and 1750, South County farmers turned from enslaving Indigenous people to enslaving thousands of Blacks from Africa to make their farms into plantations comparable to those in the South.

The group continues onward and upward, heading to a steep incline and making their way to an overlook known as “The Pinnacle.”

The students pause at a large boulder, resting weary Converse-clad feet and shooting the breeze. Ayuso then asks them what made them want to be outside, how they came to be here. One said:

“I was a city person, but when I went on my first camping experience, it opened my eyes. I was so against it at first, but when I go on these trips, I’m so happy.”

Another student reminisced about her first time camping and how waking up outside was so special.

“The last time we went camping, my friend and I woke up at 5 a.m., and waking up to the morning dew, the smell of morning dew … it was so nice,” she said.

“It’s a break from the city, life with social media, everything feeling so controlled … when you’re outdoors, you’re on your own,” another student added.

Ayuso smiled as the group continued their discussion about life, nature, and what the future holds.

“Ya’ll are gonna make me cry,” Ayuso said, laughing. “You’re making me feel all the feels. I’m blessed to be here, to be able to do this.”

Grace Kelly is a journalist for ecoRI News.

Faith vs. intellect

Exeter’s Squamscott Falls in 1907

“Never confuse faith, or belief — of any kind — with something even remotely intellectual.’’

From A Prayer for Owen Meany, a novel by John Irving about two boys growing up in the fictional small New Hampshire town of Gravesend in the 1950s and ‘60s. The town is based on Exeter, N.H., where Mr. Irving grew up. He now lives mostly in Canada but has a home in Vermont, too.

Boarding school art

Kelly McGahie, “Star Lake’’ (digital photograph), by Kelly McGahie, in the show “Hidden Treasures 5,’’ at Phillips Exeter Academy’s Lamont Gallery through Dec. 14.

This exhibit features the work of Phillips Exeter Academy employees, faculty and students across departments. The pieces span media as well, including stained glass, watercolor, photography, fiber arts and more. The artists use their different media to reflect on exploration, expression and the role of the arts at the famous boarding school in Exeter, N.H.

Water Street in downtown Exeter, an affluent town founded in 1638 and named after a town in Devon, England.

Cute but they eat songbirds

“Challenge 120: People and Their Pets: To Those I’ve Loved Before,’’ by Natasha Stoppel, in her show “Other Worlds of Now and Then,’’ at Art Up Front Street, Exeter, N.H., Sept. 6-28. The gallery explains that she’s a traveling artist who quit her corporate job in 2014 to launch Artist Explores the World, a blog and YouTube channel centered around her art and travels.’’

Water Street in downtown Exeter

— Photo by Rglowacky1

\