To honor our trees

In Alan Sonfist’s exhibit “Leaves: The Endangered Species of New England,’’ on the Bellarmine Lawn of the Fairfield (Conn.) Art Museum through June 1, 2027.

The museum explains:

“The leaves installed on the Bellarmine lawn are on loan to the Fairfield University Art Museum for the next year from the American artist Alan Sonfist (b. 1946), best known as a pioneer of the Land or Earth Art movement. These four larger-than-life aluminum sculptures of leaves (only three visible in picture above) were created in 2011 and represent several of New England’s most beloved native trees: the American Beech, the American Chestnut, the Burr Oak, and the Sugar Maple. The sculpted leaves act as reminders to honor and protect the trees, and as a warning that failure to do so could result in their extinction.’’

Making and breaking monuments in American

“Pulling Down the Statue of King George III’’ (oil on canvas), by Johannes Adam Simon Oertel, in the show “Monuments: Commemorations and Controversy,’’ Sept. 19-Dec. 20, at the Fairfield (Conn.) University Art Museum.

The museum says the show “explores monuments and their representations in public spaces as flashpoints of fierce debate over national identity, politics and race that have raged for centuries. Offering a historical foundation for understanding today’s controversies, the exhibition includes, besides the image above, such things as “a souvenir replica of a bulldozed monument by Harlem Renaissance sculptor Augusta Savage, and a maquette of New York City’s first public monument to a Black woman, Harriet Tubman, among other objects from The New York Historical's collection. The exhibition reveals how monument-making and monument-breaking have long shaped American life as public statues have been celebrated, attacked, protested, altered and removed.

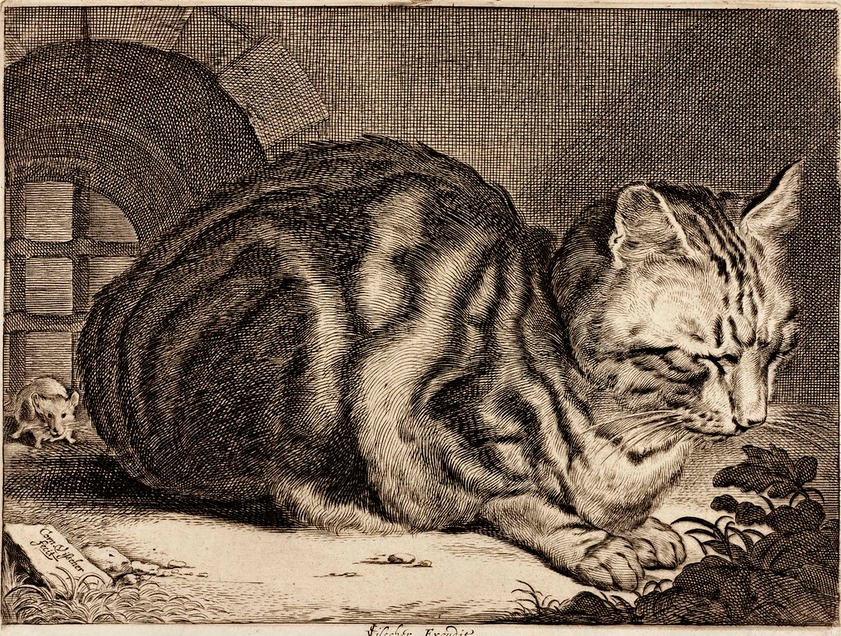

Not very edible

“Sleeping Cat'' (1657), (engraving), by Cornelis de Visscher, in the show “Ink and Time: European Prints from the Wetmore Collection,’’ at the Fairfield (Conn.) Art Museum through Dec. 21.

Image courtesy: Fairfield University Art Museum.

The museum explains that the show is “a group of woodcuts, engravings and etchings from the 15th through 18th centuries. Through three centuries of work, viewers can see the evolution of styles, tastes and depictions of life over time. This show also offers a window into the evolution of art collection, as the rise of printmaking represented a time of prosperity for artists, who could now sell their work en masse, and represented a time when the general public could access and afford fine art. ‘‘

Get out the insulin

“Ice Cream Sandwich”, by Connecicut artist Peter Anton, at the Fairfield (Conn.) University Art Museum, May 10-July 27.

The gallery says:

“Anton's work, made of wood, metal, plastic resin, oil and acrylic paints, encourages "people to think about their own relationship to food, and the memories and nostalgia that these childhood favorites conjure."

‘The ongoing tension’

“Pangolin” (steel, paper, and credit cards), by Christy Rupp, in her show “Streaming: Sculpture by Christy Rupp,’’ at the Fairfield (Conn.) University Art Museum, through April 27.

— Courtesy of the artist

The museum says:

“Understood as one of the early pioneers in the field of ecological art activism, the artist, activist and thought-leader Christy Rupp has an international reputation. Streaming {features} a survey of Rupp’s intricate collages, wall installations and free-standing sculpture, which chronicle the ongoing tension between natural systems and the environment in transition, and call our attention to our interconnectedness with non-humans and habitat – transmuting detritus gathered from the waste stream through collage and sculpture to reveal what is hidden away from common view and understanding. Informed by science and the historical representation of natural history, the artwork in this exhibition examines the way we frame our opinions of nature, using irony and wit to represent the human impact on our natural habitat.’’

Don’t let them know if you’re smiling

“She Who Wants the Rose Must Respect the Thorn’’ (fiber and mixed media), by Connecticut artist Norma Minkowitz, at the Fairfield (Conn.) University Art Museum’s show “Norma Minkowitz: Body to Soul,’’ through April 6.

— Photo courtesy of Fairfield University Art Museum

Symbolic thread

“Baggage” (fiber, resin, modeling paste and paint), by Westport, Conn.-based artist Norma Minkowitz, at the Fairfield (Conn.) University Art Museum.

—Courtesy of the artist and browngrotta arts. ©Norma Minkowitz.

“This solo exhibition surveys the artist’s four-decade engagement with the physical and symbolic properties of thread. Minkowitz reinvents traditional needlework by crocheting fantastical forms, coating them in resin and shellac to create rigid sculptures and hangings. The delicate, mesh-like surfaces of her artworks break down oppositions between soft and hard, inside and outside, body and soul.’’

Minuteman Statue at Compo Beach, Westport

‘Repeated denials’

“All the Boys (Profile 2)” (archival pigment print on gesso board), in the show “Carrie Mae Weems: The Usual Suspects,’’ at the Fairfield University Art Museum, Fairfield, Conn., through Dec. 18

The show is a photography and video exhibition focusing on “the humanity denied in recent killings of Black men, women, and children by police.” Through the work, the museum says, Weems invites viewers to reflect on what has happened time and time again in the United States of America: “Weems directs our attention toward the repeated pattern of judicial inaction—the repeated denials and the repeated lack of acknowledgement.”

1932 colorized posrtcard

An accounting of tribal art

From the show "Picturing History: Ledger Drawings of the Plains Indians, '' through Dec. 20, at the Fairfield {Conn.} University Art Museum, featuring the artwork of Plains Indians from the late 19th Century.

The museum explains that the works are called ''ledger drawings" because they were drawn on accounting ledgers; no two are the same, with some drawn with graphite, others painted with watercolors.

The museum says that the drawings are practically unknown to most scholars. When they have been studied, it's usually as historical documents, not as art.