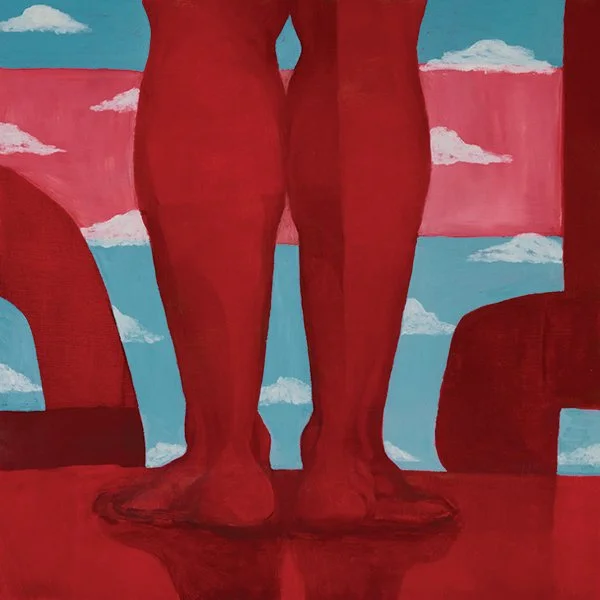

Performance anxiety

“Backstage” (oil on panel), by Jessica Gandolf, in her show “No Assembly Required,’’ at Moss Galleries, Falmouth, Maine, through April 5.

She says:

“Painting helps organize my thinking, my energy and my perceptions in a way that nothing else does. Seeing art has always made me want to make it. Creating art is a way of making sense of things, of saying something meaningful without words. Sometimes I seem to be calling attention to something at the edge of consciousness or dredging up something long buried. This can happen by making pictures or without using recognizable imagery. Sometimes it feels like magic is involved when uniting the physical presence of paint with the realm of the spirit -- magic born of some combination of anxiety and doggedness, open heartedness and luck.’’

Casco Bay from Falmouth in 191o.

‘Connected life’

From Falmouth, Maine-based artist Allison Hildreth’s show “Darkness Visible,’’ at the Center for Maine Contemporary Art, Rockland, through Jan. 7.

She has said:

“Our earth is a connected fabric of life, interdependent, a product of a long evolutionary process. Bats, the animals that weave the night sky in a chaotic flight, are, for me, the epitome of the wildness of nature.’’

Casco Bay from Falmouth, Maine in 1905.

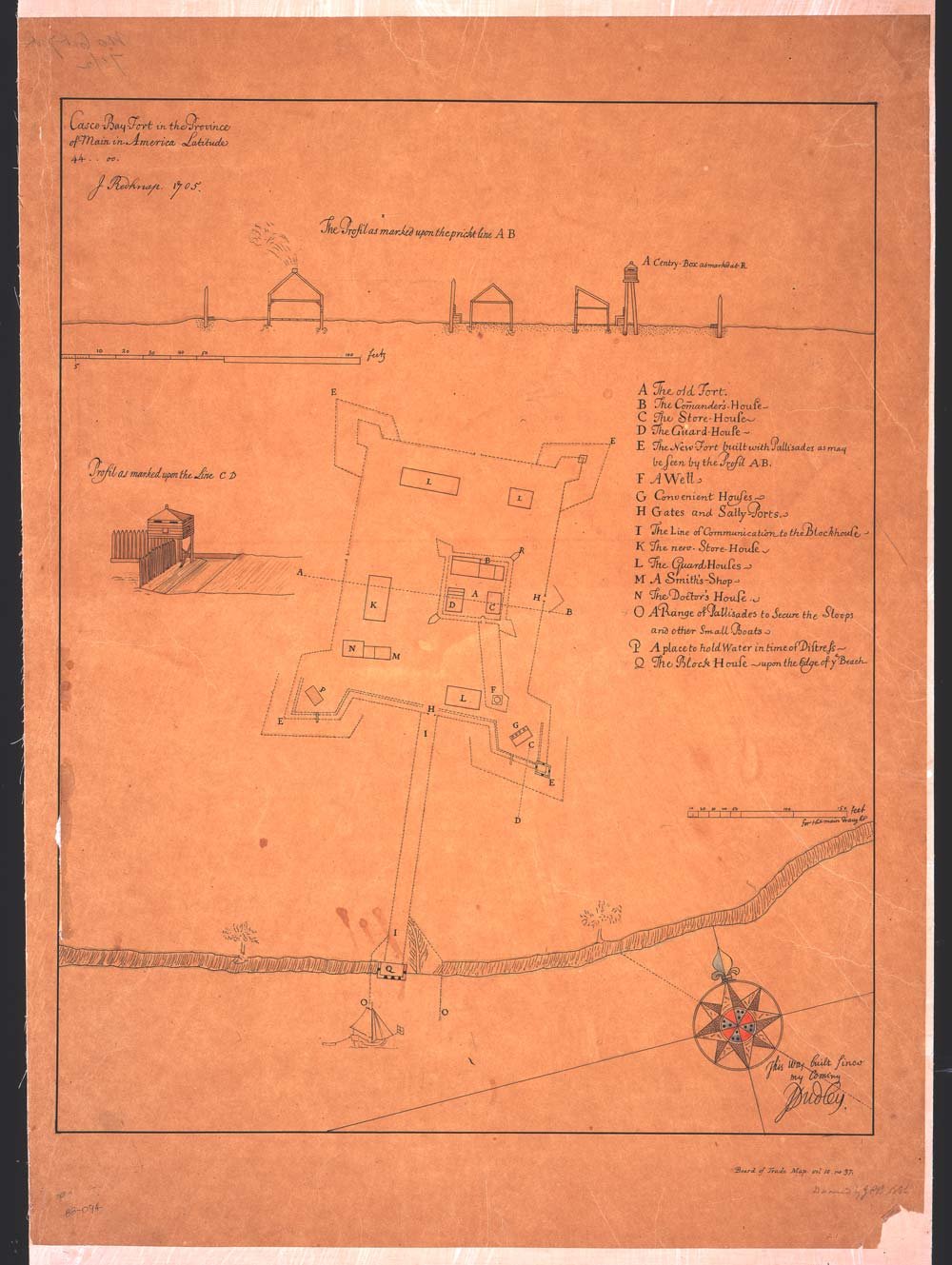

Rendering of Fort Casco, in Falmouth, in 1705.

Higher and higher

Adapted from Robert Whitcomb’s “Digital Diary,’’ in GoLocal24.com

Shoreline access continues to be a stormy issue in Rhode Island and some other coastal states. There’s constant conflict that pits beach walkers, swimmers and sitters from the general public against generally affluent shoreline house owners, who have taken over more and more of the New England coast, with many striving mightily to keep the public as far away from their houses as they can. Understandable!

There’s a measure in the Rhode Island House that attempts to end the old confusions about how high on a beach the public can go without being legally kicked off by irritated owners. (“We paid a lot of money for this place!”) It states that folks can go 10 feet landward beyond a “recognizable high tide line.’’ That’s defined as the mark left “upon tide flats, beaches, or along shore objects that indicates the intersection of the land with the water’s surface level at the maximum height reached by a rising tide.’’ (Lawyerly poetry!) That would often, but presumably not always, mean a line of seaweed, oil, shells or other debris.

None of this means that you could legally climb up the wall in front of someone’s house, whatever passes for the high-water mark.

A not very helpful 1982 state Supreme Court ruling said that the mean high-water mark is the appropriate boundary between the shoreline to which the public has access and private property, but the court said that determining the line requires “special surveying equipment and expertise.’’ What with the changes wrought by waves and storms, it can be mighty hard to find the high-tide mark in any case. Confused and/or nervous beach visitors would thus tend to move down to the low-tide mark (also not always easy to define). The new legislation doesn’t seem on the face of it to make things much easier for beach walkers to follow. And where can beach strollers sit down without being yelled at?

Inevitably, a shadowy group, with the windy title of “Shoreline Taxpayers for Respectful Traverse, Environmental Responsibility and Safety,’’ representing affluent owners, plans to fight the measure with lawsuits. Since the rich generally run America, I’d bet they’ll win; and I suspect that most of the group’s clients are from out of state.

(Some members of this same crowd also try to stop the sand from washing away in front of their houses by putting up hard barriers to catch and hold it. But that just ends up depriving the shores further down the shore of sand. Indeed, it worsens erosion.)

But wait! Rising seas caused by manmade global warming may make this issue more wrought. Estimates are that sea level will rise by almost a foot between now and 2050, and there will be more and worse hurricanes and other storms. That would push the high-tide mark (or marks), and the strolling public, further landward, toward those beach houses.

For that matter, it will also force some landowners to eventually abandon their houses, many of which shouldn’t have been put there in the first place, let alone subsidized by taxpayers through federal flood insurance and frequent repairs to beach roads by states and municipalities. Indeed, permanently removing structures from stretches of the immediate shore will be a rapidly increasing phenomenon in the next few decades. Sad. Most people love being close to the water, as real-estate prices suggest.

Will the Feds be buying out a lot of these properties through the Federal Emergency Management Agency?

Before the rise of the shoreline summer house, spawned by the money from the Industrial Revolution, few people in New England coastal communities built houses right along the shore. It was considered too insecure in the face of storms and flooding. Houses were built much higher up. So you can see that the oldest buildings in New England coastal towns are in village centers or associated with now mostly gone farms.

Part of my family has long lived in Falmouth, on Cape Cod. Some of their 18th and 19th Century houses are still standing near the town green. These people were in farming, boat building, fishing and assorted other trades. On the other hand, most of the houses around the harbors and along the beaches of the town date from the 1870’s and later, when they were built as summer places after the extension of the railroad brought affluent people, including some of my other ancestors, from the Boston area to summer on the Cape. This sort of movement was replicated on coasts, including the Great Lakes, around America.

Occasionally hurricanes or other big storms would damage or destroy the houses, but the owners would usually have enough money and/or insurance (including in the past few decades federal flood insurance) to rebuild in exactly the same insecure places.

In any event, with rapidly rising seas, that can’t go on. Let the great trek inland begin (if only a few dozen yards).

Heaven on earth?

Village Green Inn, on the town green in Falmouth Mass. It’s on the National Register of Historic Places.

— Photo by John Phelan

Statue of Katherine Lee Bates outside the Falmouth Public Library.

Never was there lovelier town

Than our Falmouth by the sea.

Tender curves of sky look down

On her grace of knoll and lea.

Sweet her nestled Mayflower blows

Ere from prouder haunts the spring

Yet has brushed the lingering snows

With a violet-colored wing.

Bright the autumn gleams pervade

Cranberry marsh and bushy wold,

Till the children's mirth has made

Millionaires in leaves of gold;

And upon her pleasant ways,

Set with many a gardened home,

Flash through fret of drooping sprar

Visions far of ocean foam.

Happy bell of Paul Revere,

Sounding o'er such blest demesne

While a hundred times a year

Weaves the round from green to green.

Never were there friendlier folk

Than in Falmouth by the sea,

Neighbor-households that invoke

Pride of sailor-pedigree.

Here is princely interchange

Of the gifts of shore and field,

Starred with treasures rare and strange

That the liberal sea-chests yield.

Culture here burns breezy torch

Where gray captains, bronzed of neck

Tread their little length of porch

With a memory of the deck.

Ah, and here the tenderest hearts,

Here where sorrows sorest wring

And the widows shift their parts

Comforted and comforting.

Holy bell of Paul Revere

Calling such to prayer and praise.

While a hundred times the year

Herds her flock of faithful days!

Greetings to thee, ancient bell

Of our Falmouth by the sea!

Answered by the ocean swell,

Ring thy centuried Jubilee!

Like the white sails of the Sound,

Hast thou seen the years drift by,

From the dreamful, dim profound

To a goal beyond the eye.

Long thy maker lieth mute,

Hero of a faded strife;

Thou hast tolled from seed to fruit

Generations three of life.

Still thy mellow voice and clear

Floats o'er land and listening deep,

And we deem our fathers hear

From their shadowy hill of sleep.

Ring thy peals for centuries yet,

Living voice of Paul Revere!

Let the future not forget

That the past accounted dear!

”The Falmouth Bell,’’ by Falmouth, Mass., native Katherine Lee Bates (1859-1929), poet, professor and social reformer best known as the author of the lyrics of “America the Beautiful’’. She’s buried in Falmouth’s Oak Hill Cemetery (close to the graves of many relatives of New England Diary editor Robert Whitcomb).

The reference to Paul Revere is that the bell in Falmouth’s First Congregational Church (built 1796), where Ms. Bates’s father was briefly the minister, was cast by Revere’s shop.

Along Vineyard Sound in the Falmouth Village of Woods Hole

— Photo by ToddC4176

'Protect the Oceans'

"Cod Larvae'' (encaustic on panel), by Pamela Dorris DeJong, in the group "Protect the Oceans: An exhibit of artists interested in protecting our oceans and shoreline habitats,'' at Highfield Hall, Falmouth, Mass., through June 18.

Monopolistically making the money -- literally

This article is about the very monied Crane Family. They (Crane & Co.) actually make the cotton-and-linen paper for America's folding money, and have for a long, long time, in western Massachusetts. And now this domestic currency-making monopoly is pushing to go much more global.

Some of the paper company Cranes have long summered in the Falmouth area of Cape Cod; so has another Crane Family, who owned the plumbing-fixtures company, Crane Co. So the locals referred to the "Bathtub Cranes'' and the "Money Cranes'' when asked who owned which big summer house.