David Warsh: Eating Instagram; McKinsey and OxyContin scandal

SOMERVILLE, Mass.

I was as surprised as anyone when a panel of prominent judges earlier this month chose No Filter: The Inside Story of Instagram, by Sara Frier, of Bloomberg News, as the Financial Times and McKinsey Business Book of the Year, so I ordered it. The publisher, Simon & Shuster, was surprised, too: the book has not yet arrived. So I re-read FT staffer Hannah Murphy’s review from last April.

The book sounds absorbing enough: how Instagram co-founder Kevin Systrom agreed to sell his start-up for $1 billion over a backyard barbecue at Mark Zuckerberg’s house and then watched in distress as Facebook bent the inventive photography app to purposes of its own. He finally walked away from the company he started, an enterprise that Frier called “a modern cultural phenomenon in an age of perpetual self-broadcasting” brought low by Facebook’s quest for global domination.

FT editor Roula Khalaf praised the book for tackling “two vital issues of our age: how Big Tech treats smaller rivals and how social-media companies are shaping the lives of a new generation.” In a beguiling online profile last summer, Frier explained how “everything changed” for technology reporters covering social media after the 2016 presidential election. Remembering the embrace-extend-extinguish tactics pioneered by Microsoft, antitrust authorities will also want to take a look.

There is, however, a larger issue about the contest itself. Given the temper of the times, I had thought either Deaths of Despair and the Future of Capitalism, by Anne Case and Angus Deaton, both of Princeton University, or Reimagining Capitalism in a World on Fire, by Rebecca Henderson, of the Harvard Business School, powerful books of unusual gravity, might capture the blue ribbon. Both specifically criticize a major McKinsey client, Purdue Pharma, and both vigorously reject the market fundamentalism that often has been imputed to the values of the secretive firm in recent decades – “shareholder value” as the only legitimate compass of corporate conduct and all that.

Granted, the prize is said by its sponsors to reward “the most compelling and enjoyable insight into modern business issues” of a given year. Previous panels have interpreted their instructions in a wide variety of ways. A McKinsey executive last year joined the judging panel. I wondered if the other members, none of them strangers to McKinsey’s lofty circles, had successfully argued to include the two critical books on the short list, before selecting a title more narrowly about “modern business issues” to avoid embarrassment to the sponsor. The awarding of literary prizes as it actually works on the inside is sometimes said to be very different from how it may look from the outside.

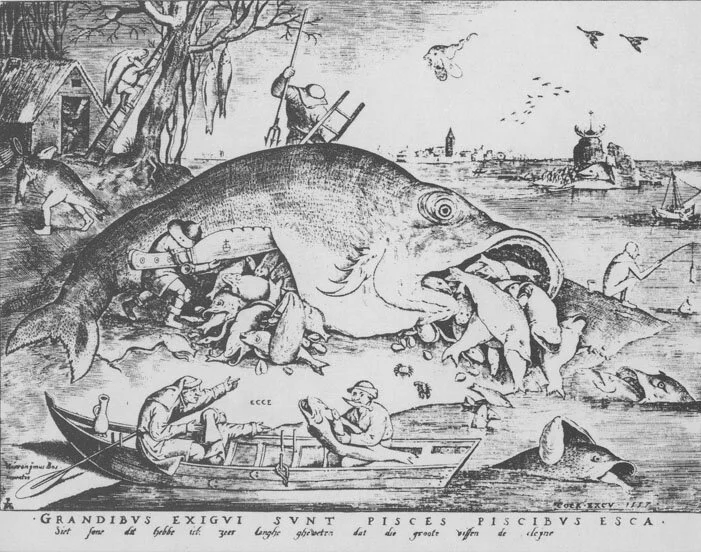

An OxyContin pill

Whatever the case, the judges could not have known about the news that broke the day before their decision was announced. The New York Times reported that documents released in a federal bankruptcy court had revealed that McKinsey & Co. was the previously unidentified-management consulting firm that has played a key role in driving sales of Purdue’s OxyContin “even as public outrage grew over widespread overdoses” that had already killed hundreds of thousands of Americans.

In 2017, McKinsey partners proposed several options to “turbocharge” sales of Purdue’s addictive painkiller. One was to give distributors rebates of $14,810 for every OxyContin overdose attributed to pills they had sold. Purdue executives embraced the plan, though some expresses reservations. (Read The New York Times story: the McKinsey team’s conduct was abhorrent.) Spokesmen for CVS and Anthem, themselves two of McKinsey’s biggest clients, have denied receiving overdose rebates from Purdue, according to reporters Walt Bogdanich and Michael Forsythe.

Moreover, after Massachusetts’s attorney general sued Purdue, Martin Elling, a senior partner in McKinsey’s North American pharmaceutical practice, wrote to another senior partner, “It probably makes sense to have a quick conversation with the risk committee to see if we should be doing anything” other than “eliminating all our documents and emails. Suspect not but as things get tougher there someone might turn to us.” Came the reply: “Thanks for the heads-up. Will do.” Elling has apparently relocated his practice from New Jersey to McKinsey’s Bangkok office, The Times’s reporters write.

Last week The Times reported that McKinsey & Co. issued an unusual apology for its role in OxyContin sales and vowed a full internal review. Sen. Josh Hawley (R.- Mo.) wrote the firm asking if documents had been destroyed. “You should not expect this to be the last time McKinsey’s work is referenced,” the firm wrote in an internal memo to employees. “While we can’t change the past we can learn from it.”

Another rethink is for the FT. The newspaper started its award in 2005, with Goldman Sachs as its co-sponsor. Tarnished by the 2008 financial crisis and the aftermath, the financial-services giant bowed out after 2013 and McKinsey took over. The enormous consulting firm is famous mainly for the anonymity on which it insists, but the Purdue Pharma scandal isn’t the first time that McKinsey has been in the news recently, especially for its engagements abroad, in Puerto Rico and Saudi Arabia. A thorough audit of its practices, reinforced by outside institutions, is overdue. In an age of mixed economies and transparency, McKinsey’s business model of mutually-contracted secrecy between the firm and the client seems outdated

Why the need for sponsorship? It would seem to be mainly a form of cooperative advertising. The cash awards to authors are lavish: £30,000 to the winner, £10,000 to each of five finalists, undisclosed sums to the judges, publicists and for advertising. That makes McKinsey’s investment a spectacular bargain, but it is something of a poisoned chalice for the FT.

The prize’s reputation as recognizing entertaining writing about important business topics is well established. Why not dispense with the money and influence? Who knows what McKinsey does and for whom? Isn’t trustworthy filtering of information the very essence of the newspaper’s business?

David Warsh, an economic historian and a veteran columnist, is proprietor of Somerville-based economicprincipals.com, where this piece first ran.

David Warsh: A great victory in vaccine making and marketing

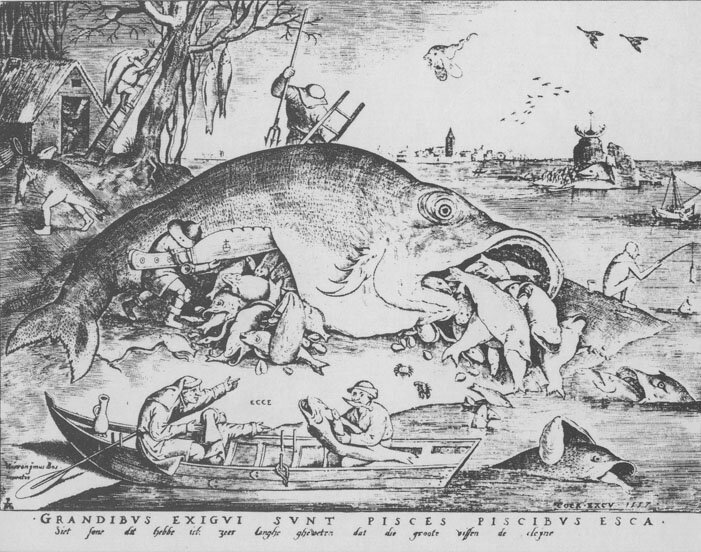

U.S. Government Accountability Office diagram comparing a traditional vaccine-development timeline to an expedited one

SOMERVILLE, Mass.

I often struggle to explain why I consider the Financial Times the best newspaper that I read. But my conviction begins with the consideration that the FT shows for my time and attention, as if it expects I have other things to do (in my case also reading The New York Times, The Washington Post and The Wall Street Journal). There are no “jumps,” all stories in the daily report end on the page where they begin. The front page displays just two stories (along with many teases of stories elsewhere in the paper); then come three pages of general news from around the world, followed by several pages of company and markets news; two pages of market data set in small type; a page of arts criticism, a full-page story (“The Big Read”); an editorial and letters page with four columns opposite, and, of course, the second most widely read page of the section, the “Lex” column of edgy newsy tidbits on the back. It is a thrifty package.

My deeper admiration, however, has to do to with the news values that the paper displays throughout. Last week presented a prime example. It takes a good deal of self-confidence to run out a story under the headline, “Trump vaccine chief proves critics wrong on Warp Speed: Industry veteran navigated political hurdles to boost drug companies’ fight against virus.”

But reporters Hannah Kuchler and Kiran Stacey had delivered a persuasive story. Since the article itself remains behind the FT paywall, I quote more extensively than I might otherwise to convey the gist. They began:

Sitting in the shadow of the brutalist health department building in Washington, with only a leather jacket for protection against an autumnal breeze, Moncef Slaoui cuts a defiant figure. Six months after the former GlaxoSmithKline executive left the private sector to become President Donald Trump’s coronavirus vaccine tsar, Mr Slaoui feels his decision has been vindicated, and critics of the ability of Operation Warp Speed to develop a vaccine in record time have been proved wrong.

“The easy answer for experts was to say it was impossible and find reasons why the operation would never work,” he told the Financial Times. But the vaccine push is now hailed as the bright spot in the Trump administration’s Covid-19 response, as products from Pfizer and BioNTech, Moderna, and AstraZeneca and Oxford university move closer to approval.

The next day, Karen Weintraub, of USA Today, produced an in-depth profile of Slaoui, a Moroccan-born Belgian-American vaccine developer and retired drug company executive. It is fascinating reading. But the authority of the FT account derived from the three experts the reporters quoted zeroing in on the management tool that Slaoui used to achieve his results, known as advance market commitments. or AMCs (and from a little Reuters sidebar that listed some of the spending on pre-approved doses by the U.S. government’s Biomedical Advanced Research and Development Authority (BARDA):

The central achievement of Operation Warp Speed had been accelerating investment in manufacturing, said Angela Rasmussen, a virologist at the Columbia University School of Public Health. “Normally, that would be a huge investment for a vaccine manufacturer to make, and potentially be a huge loss for them if they developed a vaccine that never went on to the market,” she said.

Even Pfizer, which did not take direct investment from Operation Warp Speed, benefited from having a $2bn pre-order for when its vaccine gets approved, said Peter Bach, director of the Center for Health Policy and Outcomes at Memorial Sloan Kettering. “Even if J&J or someone else beat them to the punch, they were going to get paid,” he said.

Stéphane Bancel, chief executive of Moderna, the lossmaking biotech which took about $2.5bn in government funding from different bodies, said the money was “very helpful”, covering the costs of trials and helping it to buy raw materials. “The entire planet is going to benefit from it,” he told the FT. “We are going to file [for approval] in the UK based on the US data paid for by the US government. We’re going to file in Europe and hopefully have a vaccine available in France and Spain and Italy, all paid for by the US government.”

Part of the charm of the story turns on its rarity; it hadn’t been easy for mainstream media to find nice things to say about the Trump administration. The road to Slaoui’s hiring probably leads back to Vice President Mike’s Pence’s appointment in February as head of the White House Coronavirus Task Force. As former governor of Indiana, Pence’s connections with the pharmaceutical industry are tight; Indianapolis is home to major firms, including Eli Lilly and Purdue Pharma. Much remains to be learned.

But the mechanism known as advanced market commitment is of comparatively recent origin. It is the discovery, if that is the word, of University of Chicago economist Michael Kremer, in a series of papers he wrote while teaching at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology and Harvard University some 20 years ago, culminating in the publication, in 2004, of Strong Medicine: Creating Incentives for Pharmaceutical Research on Neglected Diseases, with his wife, Rachel Glennerster, in 2004.

The new mechanisms they advocated were similar to those that in the 18th Century gave rise to the development of the naval chronometer, necessary to determining longitude at sea. Governmental “pull” methods could complement the inherently risky “push” of private research and development. AMCs – legally binding commitments to buy specified quantities of as yet unavailable vaccines at specified prices – were the most promising of the lot for bringing into existence medicines that otherwise might not pay. I wrote in 2004 that the general line of argument of the book was “one more example of why, more than ever, governments today need talented and sophisticated regulators. Technology policy has become as important as monetary policy – in some respects, maybe more so.” (I am told that governmentally guaranteed long-term purchase contracts were the backbone of creating the Indonesia-Japan LNG trade, and developing so-called private power generation in the U.S.)

I asked Kremer last week if he had been involved in the Warp Speed journey, The answer was no. He and co-authors had spoken to staff at the Council of Economic Advisers in the run-up to the creation of Operation Warp Speed. They had co-authored an op-ed article in The New York Times last May. But they had not met with Slaoui. He seems to have imbibed the basic idea as long ago as 2013, when he organized a session on the industry’s stock of common knowledge for the Aspen Ideas festival

Kremer was recognized with a Nobel Prize in economics, with two others, in 2018, for work on policy evaluation, including the work on vaccines. But I was struck when Wall Street Journal editorial-page columnist Daniel Henninger suggested last week that the scientists at the pharmaceutical companies who developed vaccines against COVID-19 were “the obvious recipient for 2021’s Nobel Peace Prize.”

There’s no doubt that we owe a considerable debt of gratitude to the scientists. But it was the administration’s Operation Warp Speed that organized their successful quests. A Peace Prize for the swift development of vaccines is a very good idea, not for President Trump or for Vice President Pence, nor even, to make a needed point, for Moncef Slaoui. It is a pretty thought, but remember that Russian and Chinese scientists also produced vaccines. Let the Norwegian parliament figure it out!

David Warsh, an economic historian and a veteran columnist, is proprietor of Somerville-based economicprincipals.com, where this column first appeared.