Frank Carini:Trying to save Timber Rattlesnakes, which play useful ecological roles in New England

Timber Rattlesnake

— Photo by Glenn Bartolotti

Text edited and excerpted from an ecoRI News article by Frank Carini

“Providence’s Roger Williams Park Zoo, partnered with New England biologists and conservationists 14 years ago to try to save the region’s remaining Timber Rattlesnake populations.

“The project aligned perfectly with Lou Perrotti’s passion and experience. The zoo’s director of conservation programs believes that it is the responsibility of state wildlife agencies and other stakeholders, such as zoos and aquariums, to protect every species considered to be threatened or endangered, no matter how big or small. They all, even venomous snakes, play a role in ecosystem health.

“For example, research has shown that Timber Rattlesnakes help keep the occurrence of Lyme disease down by preying on deer mice, a popular host of the Lyme-carrying deer tick.

“The Northeast’s population of Timber Rattlesnakes, however, remains in serious decline, because of habitat loss, road mortality, and indiscriminate killing. Perrotti has noted this species historically has had a bounty on its head, which was a significant cause of its extirpation from Rhode Island in the late 1960s.’’

Frank Carini: The brazen and well-financed disinformation campaign of the anti-wind-farm crowd

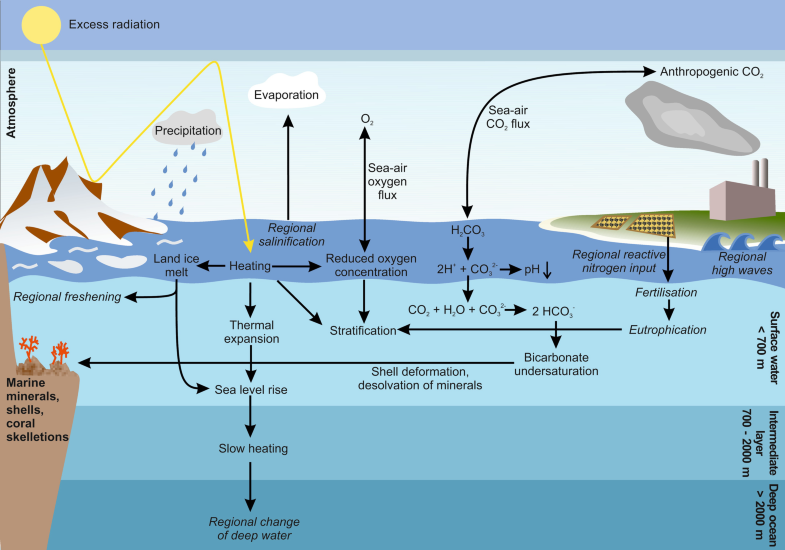

Overview of climatic changes caused by burning fossil fuel and their effects on the ocean. Regional effects are displayed in italics.

Oil spill covering kelp.

The anti-wind mob chums the waters with red herring. The conspiracy theorists continue to hide behind critically endangered North Atlantic right whales to spin tales about offshore wind. Their faux concern is nauseating.

When it comes to the real threats to the 350 or so North Atlantic right whales left on the planet — entanglements with fishing gear and strikes with ships — the mob’s ranting and raving goes largely silent, and my stomach turns.

These self-proclaimed pro-whale warriors only care about the lives of these majestic marine mammals when they fit into their manufactured hysteria about offshore wind.

Among those spreading the mob’s propaganda are southern New England firebrand Lisa Quattrocki Knight, president of Green Oceans, and Constance Gee, a Westport, Mass., resident and Green Oceans member; Lisa Linowes, executive director of the Industrial Wind Action Group Corp, also known as The WindAction Group; Protect Our Coast New Jersey; and blogger Frank Haggerty, a blowhole of offshore wind misinformation.

Their bluster is either funded by the fossil-fuel industry and/or they are wealthy coastal property owners more concerned that their ocean views will be ruined by a different type of energy infrastructure. Either way, the lives of whales, dolphins, birds, and humans living near polluting fossil-fuel operations don’t matter.

To read the whole article, please hit this link.

Drinking water under threat

EPA drinking water security poster from 2003.

From article by Frank Carini in ecoRI News

The oceans aren’t the only waters taking a beating at the hands of the most common and widespread species of primate on the planet. The elixir that sustains life is constantly abused and foolishly taken for granted by Homo sapiens.

When it comes to drinking water, climate pressures (most of which are caused by humans) and human idiocy apply an immense amount of pressure. The faucet is leaking. The dam is close to bursting.

More frequent and heavy rains are threatening drinking-water sources. Stormwater runoff and floodwaters are washing polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons, sewer overflows, and nutrients, mainly nitrogen and phosphorous from overfertilized lands, into reservoirs. The taxpayer/ratepayer cost to treat these perverted sources continues to rise.

The creep of seawater — thanks to sea-level rise and storm surge that is reaching further inland — into private wells and freshwater aquifers is a growing problem for coastal states, including the Ocean State. Prolonged drought and relentless development are forcing the pumping of more groundwater, which further impacts already stressed aquifers and private wells. It’s a vicious cycle that begins and ends with the burning of fossil fuels.

To read the whole article, please hit this link.

The great invasion

Text from article by Frank Carini in ecoRI news

A worldwide scientific intergovernmental group on biodiversity, which included a professor from the University of Rhode Island, provides evidence of the global spread and destruction caused by invasive alien species and recommends policy options to deal with the challenges of biological invasions.

The comprehensive report, released Sept. 4 by the Intergovernmental Science-Policy Platform on Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services for the United Nations, found the threat posed by invasive species introduced into new ecosystems is “enormous.”

In 2019, invasive species caused an estimated $423 billion in damages to nature, food sources, and human health. These alien invaders have also contributed to 60% of recorded animal and plant extinctions, and were the sole factor in 16% of extinctions, according to the report.

“This is the first global report on invasive alien species anywhere,” said Laura Meyerson, a URI professor in natural resources science and a contributing lead author on the report. “It’s truly an effort of scientists from around the world. The data touch on every world region, every biome and all major taxa — plants, vertebrates, invertebrates, micro-organisms, fungi.”

Invasive species pose to a threat biodiversity, ecosystem services, and human well-being. The report is designed to raise public awareness to “underpin action to mitigate the impacts of invasive alien species.”

To read the whole article, please hit this link.

Frank Carini: The staggering hypocrisy of the anti-offshore wind farm crowd

From Frank Carini’s column “Whale of a Tale: Local Anti-Wind Crowd Spins Yarns,’’ in ecoRI News (ecori.org)

”No energy source is benign. From installation to operation, they all come with consequences — environmental, societal, and cultural. Some more than others. Legitimate concerns (e.g., not infringing upon whale migration corridors) must be studied, discussed, mitigated, and/or avoided. Renewable energy shouldn’t be called clean, but it is a whole lot cleaner than fossil fuels….

“The concerns of southern New England’s anti-offshore wind crowd, however, never spill over to the polluting gas and oil platforms that mar many of the waters off the U.S. coast, especially in the Gulf of Mexico. Probably because there are no such rigs in Rhode Island Sound.

“They don’t mention sonar {which can disturb marine mammals} is used to detect leaks from offshore fossil fuel infrastructure. They fail to note ocean military training drills use sonar, and live munitions. They disregard the fact the primary causes of mortality and serious injury for many whales, most notably the North Atlantic right whale, are from entanglements with fishing gear and vessel strikes.

“Even though data show that North Atlantic right whale mortalities from fishing entanglements continue to occur at levels five times higher than the species can withstand, the anti-wind crowd isn’t calling for fishing gear to be pulled from local waters or the use of ropeless fishing technology made mandatory. They aren’t demanding vessels be equipped with technology that monitors the presence of whales in shipping lanes.

“They ignore the fact the development of offshore wind is the most scrutinized form of renewable energy. After reading this column, they will allege I and/or ecoRI News are in the pocket of Big Wind. We’re not. (A few wind energy companies have advertised with us, but they didn’t spend nearly enough to bankroll a golden parachute, or even a reporter’s salary for a month.)

“The anti-wind crowd doesn’t offer any real solutions to drastically reduce the amount of heat-trapping, polluting, and health-harming greenhouse gases that humans are relentlessly spewing into the atmosphere.’’

To read the full column, please hit this link.

Frank Carini: Turtles threatened by local poachers with global ties

A Spotted Turtle.

An Eastern Box Turtle.

From ecoRI News (ecori.org)

Rhode Island’s reptiles and amphibians face pressure from numerous threats, and for many species, removal of even a single adult from the wild can lead to local extinction, according to the state’s herpetologist.

Since the local and/or regional future for many of these species — eastern spadefoot toad, northern leopard frog, northern diamondback terrapin, to name just a few — is in doubt, removing them from nature to keep as a pet or to sell is against the law. It’s illegal to sell, purchase, or own/possess native species in any context, even if acquired through a pet store or online, according to Rhode Island law.

Turtles are especially vulnerable, according to Scott Buchanan, who became the state’s first full-time herpetologist in 2018, because some species must reproduce for their entire lives to ensure just one hatchling survives to adulthood. The Rhode Island Department of Environmental Management (DEM) staffer said it takes years, sometimes a decade or more, for turtles to reach reproductive age, if they make it at all.

Buchanan recently told ecoRI News that “broadly, across taxa” the illegal taking, or poaching, of wildlife is a “huge issue.”

“Globally, it’s considered one of the driving forces of population declines and even extinctions,” he said.

Wildlife trade experts and conservation biologists such as Buchanan point to poaching — driven by demand in Asia, Europe, and the Unified States — as a contributing factor in the global decline of some freshwater turtles and tortoises.

Tortoises and turtles grow slowly, mature late, and can, if given the chance, live for decades. This slow and steady lifestyle served them well for millions of years, but now, in the face of growing human pressures, it has become a liability.

Of the 360 known turtle and tortoise species, 52 percent are threatened, according to the International Union for Conservation of Nature Red List of Threatened Species.

A group of global turtle and tortoise experts published a 2020 paper that noted “more than half of the 360 living species [187] and 482 total taxa (species and subspecies combined) are threatened with extinction. This places chelonians [turtles, terrapins, and tortoises] among the groups with the highest extinction risk of any sizaeble vertebrate group.”

Turtle populations are “declining rapidly” because of habitat loss, consumption by humans for food and traditional medicines, and collection for the international pet trade, according to the paper’s authors. Many could go extinct this century.

Buchanan’s involvement in dealing with the impact of poachers is primarily around North American turtles. He noted turtle diversity is high globally and in the eastern United States — in the Southeast more than the Northeast, however.

But state and federal law enforcement officials and wildlife biologists consider the illegal collection of turtles to be a conservation crisis occurring at an international scale, according to Buchanan, who is the co-chair of the Collaborative to Combat the Illegal Trade in Turtles (CCITT), formed in 2018 within Partners in Amphibian and Reptile Conservation.

In the past four years, CCITT, an organization of mostly state, federal and tribal biologists, has documented some 30 major smuggling cases in 15 states. Some involved a few dozen turtles, and others several thousand.

In Rhode Island, Buchanan said there are four turtle species of concern: the eastern box turtle; the spotted turtle; the wood turtle; and the northern diamondback terrapin.

Eastern Box (species of greatest conservation need): This turtle spends most of its time on land rather than in the water. They favor open woodlands, but can be found in floodplains, near vernal pools, ponds, streams, marshy meadows, and pastures. They reach sexual maturity by about 10 years of age. Females nest in June and lay an average of five eggs in open areas with sandy or loamy soil. Eggs hatch in late summer.

Spotted (species of greatest conservation need): These turtles are sensitive to disturbance. They are usually found in shallow, well-vegetated wetland habitats, such as vernal pools, marshes, swamps, bogs, and fens. They reach sexual maturity at 7-10 years of age. Females lay an average of four eggs in moist Sphagnum moss, grass tussocks, hummocks, or loamy soil. Females probably do not lay eggs more than once a season, and females do not lay eggs every year.

Wood (species of greatest conservation need): For part of the year they live in streams, slow rivers, shoreline habitats, and vernal pools, but in the summer they roam widely across terrestrial landscapes. They reach sexual maturity around 10. During late spring, one clutch of 4-12 eggs is typically laid in nesting sites consisting of sandy soil or gravel. Eggs hatch in late summer and the young move to water.

Northern Diamondback (state endangered): Their population has suffered greatly due to poaching and habitat loss. They are found in estuaries, coves, barrier beaches, tidal flats, and coastal marshes. They spend the day feeding and basking in the sun and bury themselves in the mud at night. They reach sexual maturity at about six years old. Females lay a clutch consisting of 4-18 eggs. Some females will lay more than one clutch in a season and hatching usually occurs in late August. The young spend the earlier years of life under tidal wrack (seaweed) and are rarely observed.

All four are high-demand species in the pet trade, according to Buchanan.

“There’s a lot of illegal collection that takes place all throughout the eastern United States, including in New England and Rhode Island,” he said. “There’s a lot of recent cases that involve hundreds and thousands of turtles from those species illegally collected from individual populations, which is just totally unsustainable and has an immediate and lasting impact on those populations.”

Other turtle species that can be found in Rhode Island include eastern painted, common snapping turtle, and eastern musk.

“We have a lot of turtles for a small state,” Buchanan said. “They’re a conservation priority because of their life history. They’re just inherently vulnerable to population declines.”

Most turtles fall victim to predators before they mature. Rhode Island’s turtles are also threatened by habitat loss and fragmentation and by car strikes when crossing roads to breeding grounds.

Poaching is just another human-caused threat to their existence.

The 16 eastern musk turtle hatchlings confiscated by Rhode Island environmental police from a West Warwick resident in September. (DEM)

In late September environmental police officers from DEM’s Division of Law Enforcement found 16 Eastern Musk Turtle hatchlings, a species native to Rhode Island and the eastern United States, in the home of a West Warwick man suspected of illegally advertising them for sale on Craigslist and Facebook.

The case resulted from a week-long investigation, during which the suspect offered two hatchlings to undercover environmental police officers for purchase, according to DEM.

The suspect was charged with 16 counts of possession of a protected reptile or amphibian without a permit. The turtles were taken to the Roger Williams Park Zoo, which has a room and equipment dedicated to the care of turtles seized from the illegal turtle trade. The turtles will be released back into the wild after clearing health screenings and disease testing, according to DEM.

The 16 turtles are still at the zoo and “doing well,” according to Buchanan. He said only a minority of turtles rescued from poachers are returned to the wild, because of concerns about disease and, more importantly, not being able to determine the area from which they were taken.

The man has claimed the hatchlings were raised in captivity, but state officials believe the parents were likely taken from the wild and that the case also involves actions taken in another state. The case remains under investigation.

Last November, at New York City’s John F. Kennedy International Airport, about 100 eastern box turtles were found confined in socks inside an illegal shipment to Asia. A deadly ranavirus outbreak among the turtles confiscated by the U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service highlighted the risks and cruelty of the illegal wildlife trade, according to the New England Aquarium.

Smuggled turtles are often wrapped tightly in socks to keep them from moving. (USFWS)

Federal wildlife officials discovered the wildlife smugglers put multiple turtles, taken illegally from the wild, together into one box without food or water. Found hidden inside falsely labeled boxes, each turtle had been stuffed inside a tight sock to prevent it from moving.

The New England Aquarium took in many of the turtles and enlisted Zoo New England and Roger Williams Park Zoo to assist with treating the animals that were in poor health, suffering from dehydration and eye infections.

Buchanan said the global demand for box turtles has surged during the past few years.

A Chinese national was sentenced last year to 38 months in prison and fined $10,000 for money laundering after previously pleading guilty to financing a nationwide smuggling ring that sent 1,500 turtles worth nearly $2.3 million from the United States to China. The man used PayPal, credit cards, and bank transfers to buy the turtles from U.S. buyers advertising them on social media and reptile websites and sold them to Hong Kong reptile markets.

He trafficked in five turtle species, including the Eastern Box Turtle, protected by the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora treaty.

Turtles, especially freshwater species, are among the world’s most trafficked animals, because, as Buchanan noted, reptiles can be kept in “explicitly inhumane conditions” — say, a sock inside a cardboard box — for a significant period of time.

“Enough of them survive to make it economical [for the criminal enterprise],” said Buchanan, noting most amphibians are too fragile to keep alive for that long.

Criminal networks connect with buyers who then sell the turtles as pets, to collectors, and to commercial breeders. Some species are coveted for their colorful shells or unusual appearance. In many countries, this illegal trade is either poorly regulated or unregulated.

To help protect Rhode Island’s native species, you can submit observations of amphibians and reptiles to DEM scientists online.

“Remember never to share turtle locations online,” according to DEM. “It can be exciting to see turtles in the wild, and to share your discovery. But before you take a photo of a turtle in the wild, turn off the geolocation on your phone. If you post a turtle photo on social media, don’t include information about where you found it. Poachers use location information to target sites.”

There are a few reptiles and amphibians that can hunted legally in Rhode Island: snapping turtles, bullfrogs, and green frogs. A current fishing, hunting, or trapping license is required and hunting/trapping must be conducted in compliance with season and size regulations. All animals harvested must be killed immediately following capture, as possession of live turtles or frogs is illegal.

Turtle traps must be marked with the trapper’s name and address, checked every 24 hours, and set in a manner that will allow turtles access to air, according to DEM. All bycatch must be released immediately at the location where the trap was set.

“This illegal collection of turtles … I think most people have a perception that it’s disparate or kind of small-time … it’s just some yahoos out there collecting a few turtles, when in fact it’s perfectly accurate to say the norm is international criminal syndicates that are driving the trade in turtles that leads to the illegal collection here in the U.S.,” Buchanan said. “There’s often times a local collector who’s in contact with a middleman who’s in contact with a criminal network that’s also involved in things like drug trafficking and human trafficking.”

Note: The sexual maturity and nesting habits of the four turtle species of concern in Rhode Island are based on their life and conditions here. For more information about the turtles of Rhode Island, click here. To watch a short U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service video about the importance of turtles and the threat from poaching, click here.

Frank Carini is co-founder and senior reporter for ecoRI News.

Frank Carini: In search of old-growth forests

An old beech tree in the Rhode Island woods.

— Photo by Frank Carini

From ecoRI News (ecori.org)

WARWICK, R.I. — Last winter Nathan Cornell accidentally found himself “walking into a different world,” one that isn’t protected from human intervention. For the past two years, the University of Rhode Island graduate has been searching for old-growth forests in Rhode Island.

He found one not far from his Warwick home.

His hunt for old-growth forests led him and Rachel Briggs to found the Rhode Island Old Growth Tree Society, a nonprofit determined to locate, document, map and advocate for the preservation of all remaining old-growth and emerging old-growth trees and forests in the state. This means trees and groups of trees that are 100 years old and older.

Cornell, with the help of licensed arborist Matthew Largess, owner of Largess Forestry, in North Kingstown, R.I. has so far identified more than a dozen potential old-growth pockets, including on the University of Rhode Island campus in South Kingstown and in Cranston, North Kingstown, Portsmouth, Warwick and West Greenwich.

In mid-July, the 24-year-old took this ecoRI News reporter on a walking tour of the hidden-in-plain-sight “5- to 10-acre” Warwick property owned by the Community College of Rhode Island and Kent Hospital. To listen to the audio story, click the bar at the top.

Anyone interested in joining the Rhode Island Old Growth Tree Society, can contact Cornell at ncornell@my.uri.edu. To read an opinion piece written by Cornell and recently published on ecoRI News, click here.

Frank Carini is co-founder and a journalist at ecoRI News.

Frank Carini: Will federal reprieve be enough to save these very fast sharks?

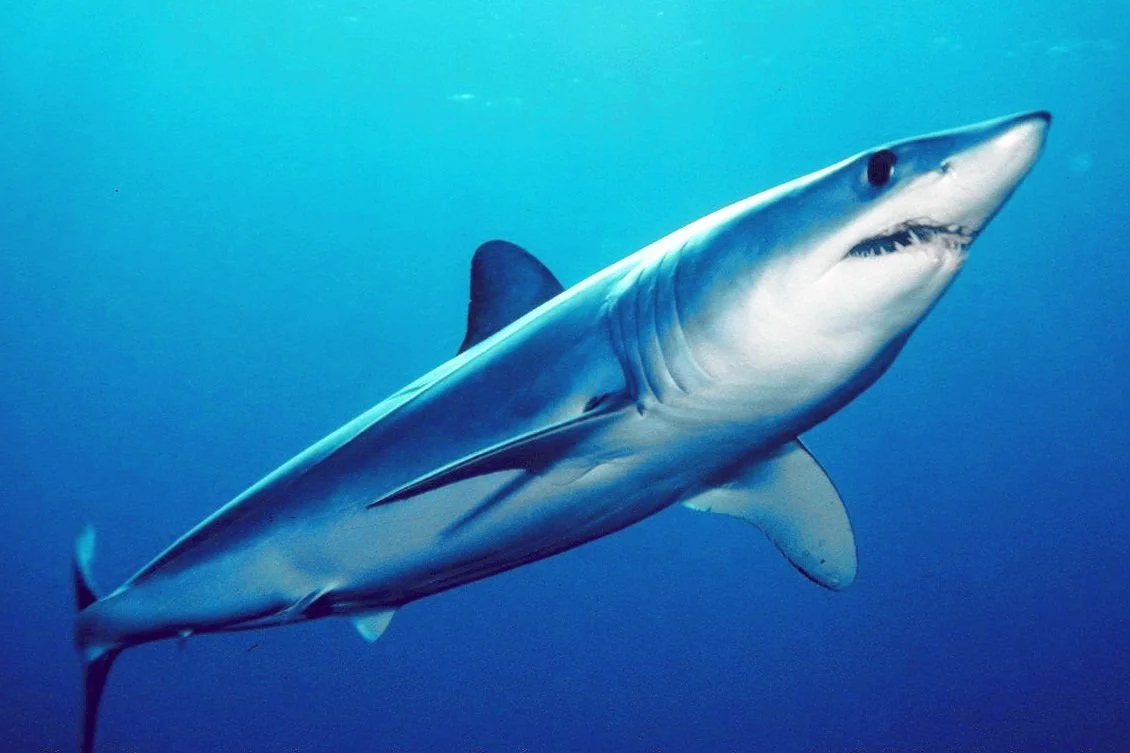

An Atlantic shortfin mako shark

From ecoRI News (ecori.org)

The world’s fastest-swimming shark is about to get a reprieve from overfishing.

Beginning July 5, the landing or possession of Atlantic shortfin mako sharks in the United States has been prohibited. This rule applies to commercial fishermen, recreational anglers and any dealers who buy or sell shark products. These sharks frequent southern New England waters.

The ban includes sharks that are dead or alive when captured, according to the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration’s National Marine Fisheries Service (NOAA Fisheries).

The recent decision has long been supported by shark-research organizations concerned about the significant issues that this species faces. Defenders of Wildlife and the Center for Biological Diversity sent a notice June 28 to Gina Raimondo, U.S. secretary of commerce, and Janet Coit, assistant administrator for NOAA Fisheries, of their intent to sue for failing to protect the shortfin mako shark under the Endangered Species Act.

“The shortfin mako shark is the world’s fastest-swimming shark, but it can’t outrace the threat of extinction,” Jane Davenport, a senior attorney at Defenders of Wildlife, is quoted in a press release about the organizations’ intent. “The government must follow the science and provide much-needed federal protections as quickly as possible. This will demonstrate America’s leadership in fisheries and ocean wildlife conservation both at home and on the world stage.”

The shortfin mako is a highly migratory species whose geographic range extends throughout the world’s tropical and temperate oceans. They can reach a top speed of 45 mph, and, like tunas and the white shark, shortfin mako sharks have a specialized blood vessel structure — called a countercurrent exchanger — that allows them to maintain a body temperature that is higher than the surrounding water. This adaptation provides them with a major advantage when hunting in cold water. As an apex predator, the species is an integral part of the marine food web.

The species, however, faces a barrage of threats, especially overfishing from targeted catch and bycatch. The species’ highly valued fins and meat incentivize this overexploitation.

“The shortfin mako shark has long been a target of commercial fisheries and consumers due to its excellent taste, and to sport fishermen for its spectacular strength and leaping ability,” said Jon Dodd, executive director of the Wakefield, R.I.-based Atlantic Shark Institute. “Unfortunately, those are the same issues that have resulted in the significant population decline of this iconic shark that required this complete and unprecedented closure.”

Dodd noted female mako sharks don’t reproduce until they are about 20 years old and weigh some 600 pounds.

“I’ve seen hundreds of mako sharks and exactly one that size in all my years researching this spectacular shark,” he said. “It’s amazing that they can even reach that age and size with all the fishing pressure and risks they face.”

Since mako sharks have few young, and they take time off between giving birth, Dodd said the numbers don’t favor their long-term survival without significant management changes.

Three years ago the International Union for Conservation of Nature classified the shortfin mako as “endangered” on its Red List of Threatened Species.

“The Fisheries Service failed to protect the shortfin mako despite an international scientific consensus that conservation action is urgently needed,” Alex Olivera, a senior scientist at the Center for Biological Diversity, said in the June 28 press release that quoted Davenport. “Even as the rest of the world scrambles to save these sharks from extinction, they have no protections under the U.S. Endangered Species Act. That needs to change.”

On NOAA Fisheries’ species directory Web page for the shortfin mako shark, it reads: “U.S. wild-caught Atlantic shortfin mako shark is a smart seafood choice because it is sustainably managed and responsibly harvested under U.S. regulations.”

On the same page the federal agency notes that, according to the 2017 stock assessment, shortfin mako sharks are “overfished and subject to overfishing.”

In a 2019 assessment, the International Commission for the Conservation of Atlantic Tunas (ICCAT) estimated that as much as 4,750 metric tons of mako shark were being taken on an annual basis.

“It was time to give the mako shark a break, but even so, we are still looking at a recovery that will take until 2070,” Dodd said. “This is not a quick fix by any means, and the mako still faces significant challenges.”

If ICCAT provides for U.S. harvest in the future, NOAA Fisheries could increase the shortfin mako shark retention limit, based on regulatory criteria and the amount of retention allowed by ICCAT. Until that happens, the retention limit will remain at zero, according to the agency.

Frank Carini is senior reporter and co-founder of ecoRI News.

Frank Carini: Warming waters are changing fish mix

From ecoRI.org

For generations, winter flounder was one of the most important fish in Rhode Island waters. Longtime recreational fisherman Rich Hittinger recalled taking his kids fishing in the 1980s, dropping anchor, letting their lines sink to the bottom, waiting about half an hour and then filling their fishing cooler with the oval-shaped, right-eyed flatfish.

Now, four decades later, once-abundant winter flounder is difficult to find. The harvesting or possession of the fish is prohibited in much of Narragansett Bay and in Point Judith and Potter ponds. Anglers must return the ones they accidentally catch to the sea.

Overfishing is easily blamed, and the industry certainly bears responsibility, as does consumer demand. But winter flounder’s local extinction isn’t simply the result of overfishing. Sure, it played a factor, but the reasons are complicated, from habitat loss, pollution and energy production — i.e., the former Brayton Point Power Station, in Somerset, Mass., pre-cooling towers, when the since-shuttered facility took in about a billion gallons of water daily from Mount Hope Bay and discharged it at more than 90 degrees Fahrenheit.

The climate crisis, however, is likely playing the biggest role, at least at the moment, by shifting currents, creating less oxygenated waters and warming southern New England’s coastal waters. These impacts, which started decades ago, have and are transforming life in the Ocean State’s marine waters. The changes also impact ecosystem functioning and services. There’s no end in sight, as the type of fish and their abundance will continue to turn over as waters warm.

Rhode Island’s warming water temperatures are causing a biomass metamorphosis that is transforming the state’s commercial and recreational fishing industries, for both better and worse. The average water temperature in Narragansett Bay has increased by about 4 degrees Fahrenheit since the 1960s, according to data kept by the University of Rhode Island’s Graduate School of Oceanography.

Locally, iconic species are disappearing (winter flounder, cod and lobsters), southerly species are appearing more frequently (spot and ocean sunfish) and more unwanted guests are arriving (jellyfish that have an appetite for fish larvae and, in the summer, lionfish, a venomous and fast-reproducing fish with a voracious appetite).

Dave Monti, a charter boat captain for the past two decades, has been fishing in Rhode Island and Massachusetts waters for 45 years. He’s seen a lot of change in a fairly limited amount of time.

He said the type of fish in Rhode Island’s marine waters today is much different than a decade ago. He pointed to the impact of a changing climate. Warm-water fish such as black sea bass, summer flounder and scup are here in abundance, according to Monti. These species are now an integral part of his charter business.

“It would have been unheard of 10 years ago to say black sea bass would be so abundant in our waters, and that it would be a big part of my charter business,” Monti said.

This transfer of fish along the Atlantic Coast is having an impact on commercial fisheries, most notably regarding the issue of assigning stock allocations.

For example, Monti noted that summer flounder moving north has created havoc with catch limits. He said Mid-Atlantic vessels, which possess the summer flounder quotas but now have fewer of the fish in their waters, have moved up the East Coast to fish. New England boats now have the fish in their waters but little allocation.

He said that the laws that govern commercial fishing need to keep up with the impacts of the climate crisis. He also noted that as warming waters change the type and abundance of fish in different regions, commercial fishermen have to retool their boats and gear and learn how to catch the species new to their waters.

Hittinger, first vice president of the Rhode Island Saltwater Anglers Association, attributes the species changes he has witnessed in local waters, at least in part, to rising water temperatures.

When the Warwick resident started fishing regularly more than four decades ago, Hittinger said he caught cod and pollack off Block Island and winter flounder in all of the state’s bays. He noted that most of these fish are largely gone, replaced by warm-water species.

Speaking as a recreational angler, Hittinger said the changing of the species found in Rhode Island’s salt waters isn’t necessarily his concern. His concern lies with regulation that is slow to change with the times. He used black sea bass as an example, noting that Rhode Island’s recreational fishing restrictions on the species, implemented by the Mid-Atlantic Fishery Management Council, were set 20 years ago. Now, he said, there are a lot more of them.

Black sea bass caught in Rhode Island waters must be at least 15 inches in length and the limit is three or seven per angler per day depending on the season. Hittinger noted that in New Jersey, where the fish is becoming slightly less plentiful, keepers must be at least 12.5-13 inches and the daily allowance is higher.

As the waters off the East Coast continue to warm, the Mid-Atlantic Fishery Management Council and the New England Fishery Management Council will likely be hearing similar concerns.

Stephen Hale, a long-time marine ecologist at the Environmental Protection Agency’s Atlantic Coastal Environmental Sciences Division Laboratory in Narragansett, said marine animals are shifting northward along the Atlantic Coast in response to the changing climate. He said the movement of a new species into an area can cause ecosystem disruption and that the depletion of key species from an area can lead to economic and social changes.

Hale noted that if your preferred habitat was warming to a level you found intolerable, you would basically have three choices: adapt (install an air conditioner, for example); move to a cooler locale (say Maine); or stay where you are and suffer the consequences (heat exhaustion, heat stroke, death).

He said many of the planet’s other species can only exercise the second option, while others are stuck with the third.

Along the East Coast numerous marine species, including bottom-dwelling invertebrates such as clams, snails, crustaceans and polychaete worms, have shifted their ranges poleward in response to rising water temperatures caused by the global climate crisis. Cold-water species such as cod, winter flounder and American lobster are moving to cooler locales.

Hale said species are trying to maintain their preferred thermal niche by moving poleward or into deeper water.

The Saunderstown resident, who retired from the EPA in 2018 after 23 years at the Narragansett lab, co-authored a 2017 study that covered two biogeographic provinces along the Atlantic Coast: Virginian, Cape Hatteras, N.C., to Cape Cod; and Carolinian, mid-Florida to Cape Hatteras.

The authors found that bottom water temperature increased 2.9 degrees Fahrenheit from 1990 to 2010. They also noted that the center of distribution of 22 out of 30 species studied shifted north in response to increasing water temperatures. Seven species shifted south, but moved just one-third the distance of the northward-movers.

“Fishermen are adaptive,” said Monti, a strong supporter of renewable energy development to address the climate crisis. “Every day is different with tides, currents, wind and bait. Warming waters and climate change are just additional factors. Regions are losing and gaining fish. It’s not going to end.

Frank Carini is editor of ecoRI.org.

Frank Carini: Plastic pollution is burying a coastline

Rhode Island beach scene

—Photo by Frank Carini

From ecoRI News (ecori.org)

Dave McLaughlin has been organizing, leading and documenting Rhode Island shoreline cleanups for the past 15 years, and he’s noticed one item, which comes in all shapes, sizes and colors, becoming increasingly prevalent: plastic.

When the Middletown-based nonprofit he leads, Clean Ocean Access, began cleaning up Aquidneck Island’s coastline in 2006, staff and volunteers found bed frames, tires, refrigerators, glass bottles, aluminum cans and lots of fishing gear.

Today, a deluge of plastic now swamps the shoreline. McLaughlin said the petroleum-based tidal wave began about a decade ago. Besides the typical debris of plastic bags, straws, Capri Sun pouches, Styrofoam cups, candy wrappers and omnipresent cigarette butts — most filters are made of cellulose acetate, a plastic — this evolving pollution now features Jewel pods and the explosion of single-use plastics and multilayered packaging.

Multilayered packaging has several thin sheets of different materials, such as aluminum, paper and plastic, that are laminated together. It’s not made for recycling.

This growing amount of plastic packaging is washing up on shorelines worldwide, including along the Ocean State’s 420 miles of coast — arguably the state’s most important economic engine. In 2015, about 45 percent of plastic waste generated globally was from packaging materials, according to a 2018 white paper. A 2017 report found up to 56 percent of plastic packing manufactured in developing countries consists of multilayered materials.

It’s been estimated that every U.S. household uses nearly 60 pounds of multilayered packaging annually. Most isn’t or can’t be recycled, and much, like other plastic-related trash, ends up in the sea or washed up along the coast.

As of 2019, Clean Ocean Access had held 1,171 cleanups and removed nearly 69 tons of marine debris — about 118 pounds per cleanup — from Aquidneck Island’s shoreline and out of its coastal waters. Of the 14 most common items collected on land, half have been predominantly plastic: straws and stirrers; 6-pack holders; food wrappers; caps and lids; bottles; bags; and toys, according to the organization’s 2006-2019 Clean Report.

Of the 13 most common items pulled from the marine waters of Portsmouth, Middletown and Newport, five are plastic heavy: bleach and cleaning bottles; fishing line; sheets and tarps; strap bands; and buoys and floats.

All of these plastic items, on land and in the water, continue to break down into smaller and smaller toxic pieces that work their way up the food chain.

July Lewis, volunteer manager for Save The Bay, has been involved with shoreline cleanups since 2007. She said the one trend that is inescapable is the growing amount of microplastics and “tiny trash” — what she called pulverized pieces of bottle caps, cups and other plastics — that litter Rhode Island’s coastline.

“We are seeing more and more of it every year,” Lewis said. “It’s become part of the ecosystem.”

Peter Panagiotis, the well-known professional surfer better known as Peter Pan, has been surfing in Rhode Island waters, mostly along the coast of Narragansett, since 1963. He told ecoRI News that plastic now litters the coastline.

“There’s more plastic pollution, especially in the winter there is garbage everywhere,” the Pawtucket resident said. “Plastic pollution is the problem. There’s a lot more plastic garbage.”

Plastic debris makes up a growing amount of the material that is picked up annually during Save The Bay coastal cleanups. In 2019, 2,807 volunteers collected 7.8 tons of trash along 94 miles of shoreline — or about 5.5 pounds per person and 166 pounds per mile.

Of the material collected that year, plastic and foam pieces less than 2.5 centimeters long accounted for 27 percent of all the rubbish collected — 42,841 pieces of tiny trash. Microplastics, pieces less than 5 millimeters long (0.5 centimeters), are harder to see and pick up, but they are a growing presence.

The repulsive 2019 haul included plenty of other plastic: candy and chip wrappers (11,136); bags (6,213); straws and stirrers (4,629); lids (1,942); and utensils (1,050).

For nearly a decade, Geoff Dennis has been a one-man cleanup crew for the Little Compton shoreline. Dennis “got a taste for trash” while walking along Goosewing Beach in 2012.

“It really bothers me. The first time I walked with the dog, I came back with over 100 Mylar balloons,” he told ecoRI News in 2017. “If I can start a conversation with people about it, that’s great. But most people just don’t care.”

Between 2012 and 2020, the longtime quahogger picked up 35,607 pieces of trash along the banks of the Sakonnet River and at Goosewing Beach Preserve and a few other places. The vast majority of it was some form of plastic, from bottles to wads for shotgun shells.

In fact, the amount of plastic he has collected just along Little Compton waters is shocking:

Balloons made from the resin polyethylene terephthalate, a clear, strong and lightweight plastic belonging to the polyester family and commonly referred to as Mylar, a registered trademark owned by Dupont Tejjin Films (2012-20): 8,510. That total doesn’t include the 1,194 latex balloons he collected in 2019 and ’20.

Plastic bottle caps (2017 and 2020): 4,107.

Plastic shotgun shells (2017 and 2020): 1,552.

Plastic wads for shotgun shells (2017 and 2020): 527.

Plastic straws (2016-19): 1,526.

Plastic snack bags (2015-2020): 867.

Plastic bags (2018-2020): 440.

Plastic and foam cups (2018-2020): 386.

Plastic coffee cup lids (2020): 94

K-Cup pods (2019 and 2020): 210.

Plastic nips (2020): 207.

Plastic lighters (2017 and 2020): 188.

Plastic bottles and aluminum cans (2012-2020): 15,324.

In some places along Rhode Island’s marine waters, such as Fields Point in Providence, plastic pollution is now part of the shoreline environment. (Save The Bay)

Lewis noted that in some places, such as Fields Point, at the head of Narragansett Bay in Providence, plastic litter is indistinguishable from the natural world. She said most of this shoreline litter is generated from eating, drinking and smoking.

Save The Bay, too, is finding plenty of plastic flotsam and jetsam bobbing in Rhode Island’s coastal waters. The Providence-based organization is playing a leading role in establishing baseline data on the amount of microplastics within the Narragansett Bay watershed. The goal is to highlight this growing problem and draw attention to regional efforts to eliminate single-use plastics, such as cups, straws and bags.

The three staffers — Michael Jarbeau, Kate McPherson and David Prescott — largely responsible for conducting Save The Bay’s trawls for plastic have been surprised by how much they have found in local waters. When they started, they expected some microplastic trawls would come up empty. They’re still waiting for that to happen.

The crew has done more than 24 surface trawls, and every one has produced plastic bits, from nurdles, the raw building blocks for plastic bottles, bags and straws, to microfibers from polyester fleeces and other synthetic clothing to microbeads, which are used in exfoliating scrubs and in some toothpastes.

All of this overused plastic is changing the composition of Rhode Island’s marine waters. These petroleum byproducts don’t biodegrade. They remain in the environment for centuries. Their long-term impacts on environmental and public health aren’t close to being fully understood. Their impact on the natural world, however, has already been well documented.

Plastic bags float in Narragansett Bay, Block Island Sound and the Ocean State’s other marine waters like jellyfish. Turtles, whales and other sea animals often mistake them for food, causing many to starve or choke to death.

Adult seabirds inadvertently feed tiny trash to their chicks, often causing them to die when their stomachs become filled with fake food. As plastic breaks down into smaller fragments — microplastics may contain toxic chemicals as part of their original plastic material or adsorbed environmental contaminants such as PCBs — fish and shellfish become increasingly vulnerable to the toxins these polluted particles collect.

At least two-thirds of the world’s fish stocks are suffering from plastic ingestion, including local seafood favorites striped bass and quahogs.

On the positive side of the Ocean State’s shoreline trash problem, both McLaughlin and Lewis said they are seeing less dumping of big items, such as tires and appliances.

clean-ups by volunteers seem futile, a new batch will soon appear. Why aren't officers of the companies that make these plastics required to clean it up or pay someone to do so?

Frank Carini is editor of ecoRI News.

Frank Carini: When you let the sands shift naturally

Dunes on Napatree Point

WESTERLY, R.I.

In late October 2012, about a day after Superstorm Sandy’s initial surge battered much of southern New England’s coast, especially its open-ocean shoreline, Janice Sassi navigated her way through a parking lot here filled with “mountains of mud” to find a “moonscape.”

“The dunes were completely flat,” recalled Sassi, manager of the 86-acre Napatree Point Conservation Area. “I thought it was done. It looked like one big beach.”

Sandy had ripped chunks of beachgrass from sections, and one area was forced back some 30 feet. At that moment and for days after, Sassi was concerned about Napatree Point’s future.

Her friend Peter August, a now-retired University of Rhode Island professor and a Napatree Point science adviser, put her racing mind at ease. The former director of URI’s Coastal Institute told her the resilient peninsula that offers sweeping views of Little Narragansett Bay, Block Island Sound, and New York’s Fishers Island would be fine. He reminded her that Napatree Point had previously survived one of the most destructive and powerful hurricanes in recorded history.

The hurricane of 1938, also known as the “Great New England Hurricane,” smashed the peninsula’s 39 2- and 3-story houses that stood just a few feet from the churned-up fury of the Atlantic Ocean. The 3- to 4-foot-high wall in front of those summer homes did nothing to prevent their destruction.

Storm waves broke over roofs and plowed “through the cement seawall as if it were transparent,” R.A. Scotti wrote in her 2003 book, Sudden Sea: The Great Hurricane of 1938.

“If you build on a barrier beach, you are toying with nature,” she wrote.

On the other side of the Napatree Point peninsula, most if not all of the private docks that extended into Little Narragansett Bay were reduced to kindling. Some residents waited out the 100-year storm in the remains of decommissioned Fort Mansfield. Fifteen people died.

The historic ’38 storm, much more so than Superstorm Sandy nine years ago, pummeled the 1.5-mile-long, sand-swept peninsula that curves away from the affluent village of Watch Hill. It severed the connection to Sandy Point, now a mile-long island shared by Rhode Island and Connecticut. In the eight decades since Sandy Point was left afloat, the island has drifted one and a half miles to the north.

More than a century earlier, Napatree Point, which was then densely forested — its name reportedly derives from nap or nape (neck) of trees — was significantly altered by another hurricane. The Great September Gale of 1815 “wiped it clean” and no tree has grown there since, according to Scotti’s book.

Following the hurricane of 1815, Napatree Point was significantly developed, and saw the construction of a boarding house and a hotel. By the end of the century, construction of Fort Mansfield had begun.

Though Sassi, then less than three years into her job after a career in law enforcement, was initially skeptical of August’s reassurances that her beloved Napatree Point would rebound, she’s thankful it did. She said it took about five years for the conservation area to completely repair itself. The beachgrass regrew, and the dunes regained their elevation.

Napatree Point was able to heal itself because humans have given it room to breathe. After the ’38 hurricane, one of the most financially destructive storms on record, developers looking to rebuild the summer cottages and construct other structures were rebuffed.

With no roads, homes, and hardened structures obstructing Mother Nature, Napatree Point has been allowed to change with the times. August noted that the barrier beach has the space to continually wash back over itself.

“It doesn’t erode away. It just moves,” said August, who founded URI’s Environmental Data Center three decades ago. “Napatree Point was 80 acres when the hurricane of ’38 struck; it’s 80 acres now, just in a different place. Napatree Point will always be here. It rolls with the punches. It gets changed but still exists.”

The Hope Valley resident said the geology of Napatree Point is a perfect example of how a barrier dune ecosystem works naturally. He explained that when Napatree Point is hit by big storms, such as the Great New England Hurricane or Superstorm Sandy, and wave action and tidal surge punch through the dunes, it creates wash-over fans on the backside, meaning the position of the peninsula’s dunes change; they aren’t lost.

“They’re rolling over themselves and they can do that because we’re letting the sand go where the sand wants to go,” August said.

Napatree Point is owned, managed and protected by a partnership of different interests: the Watch Hill Fire District, the Watch Hill Conservancy, which employs Sassi, the Town of Westerly, the state, and a few private landowners. Conservation easements protect it from future development.

In the summer, this slender strip of land — the average width is 517 feet — at the mouth of Little Narragansett Bay, where the Pawcatuck River empties into Block Island Sound, is overrun with tourists, boaters, beachgoers, hikers, anglers and nature observers. Finding a scrap of beach can be difficult, and some areas are roped off for important visitors, most notably piping plovers and American oystercatchers, both of which nest in the sand.

Sassi is thrilled that Napatree Point is so popular, but all the human visitors have an accumulating impact on the peninsula’s delicate dune system. The West Warwick, R.I., resident noted that the fact there is no development makes it easier for the small peninsula to defend itself from a changing climate and human intrusion.

The conservation area, however, isn’t immune to sea-level rise and other stressors associated with the climate crisis. About three years ago, Sassi and August began noticing that the entrance to Napatree Point, through a large parking lot off Bay Street that is lined with boutique shops and a mix of culinary options, began to flood during extremely high tides.

It’s now beginning to flood even during normal high tides. As sea levels rise and more frequent flooding occurs, access to the peninsula, at least via land, will become more and more restricted unless something is done. August said plans are underway to elevate the entrance, which laps up against Watch Hill Harbor.

Napatree Point is a barrier beach that has been shaped and reshaped by storms, sometimes profoundly, as was the case 206 years ago, 83 years ago, and nine years ago. The peninsula is composed of more sand than soil and its shoreline is worked upon daily by ocean waves and the tide. Like most barrier beaches, especially those with no human-made structures, Napatree Point is constantly in a state of flux. Since 1939, it has shifted north, toward Little Narragansett Bay, some 200 feet, according to mapping by the Coastal Resources Management Council.

The peninsula, however, is much more than a summer destination and a birdwatcher’s paradise. It’s also a habitat provider and a storm protector.

This fragile yet pliable barrier beach helps protect Westerly’s mainland. And to help protect Napatree Point’s dynamic ecosystem — and, thus, tourist-friendly Watch Hill — from storm surge, coastal erosion, and human visitors, a number of restoration projects have been undertaken.

During the past dozen years, some 4,000 native plants, such as seaside goldenrod, beach plum, swamp milkweed and groundseltree, have been added to help anchor Napatree Point’s shifting sands — their dense root mats keep erosion in check — and to attract pollinators.

Split-rail fences have been erected and signs posted to keep visitors and their wheeled coolers from making their own paths from the peninsula’s protected side to its open-ocean side. At one point several years ago, 50 crossover paths had been plodded through Napatree Point’s dunes and vegetation. Dinghies and Zodiacs land on the Little Narragansett Bay/Watch Hill Harbor side, before their occupants traverse the peninsula to the Atlantic Ocean side, where they lie in the sun, swim, and bodysurf.\

This tireless restoration work piloted by Sassi, August, Hope Leeson, Bryan Oakley and others has made Napatree Point a national model for stewardship, an important distinction since the area caters to an abundance of life, including mussel beds, bats, minks, foxes, deer, monarch butterflies, and a plethora of birds.

Off its coast are some of the biggest and healthiest eelgrass beds in Rhode Island waters. These vital marine ecosystems provide foraging areas and shelter to young fish and invertebrates, spawning surfaces for sea life, and food for migratory waterfowl. Gray and harbor seals hang out on the open-ocean side of the peninsula. In the winter, rafts of sea ducks are a common sight in the waters off the peninsula.

The Audubon Society has recognized Napatree Point as a globally important bird area. Veteran Rhode Island birder Rey Larsen has identified more than 300 different species of birds on the sandy, wind-swept peninsula.

The Napatree Point lagoon, about 3.5 feet deep in the middle, is home to a half-dozen different kinds of fish, including the American eel. It’s also an important horseshoe-crab nursery. The entrance to the 10-acre lagoon, from Little Narragansett Bay, is the peninsula’s most rapidly changing part, according to August. He said the entrance to the lagoon has moved a few times during the past decade alone.

Napatree Point, unlike much of Rhode Island’s built-up coastline, is better positioned to handle the climate crisis because humans are allowing its sands to shift naturally.

“The most important thing we can do is get people excited about Napatree Point so they want to protect it,” Sassi said.

For a wealth of science, stewardship, and monitoring information about the Napatree Point Conservation Area, click here.

Frank Carini is editor of ecoRI News.

Watch Hill and Watch Hill Cove from the eastern end of Napatree Point

Frank Carini: The vast poisoning that goes with maintaining lawns

From ecoRI News (ecori.org)

The amount of pollution, from noise to air to water, created to maintain green carpets and immaculate yards is jarring. Lawn mowers, weed whackers, leaf blowers, pesticides, herbicides, fungicides and fertilizers. Much of this effort is powered by or made from fossil fuels.

Lawn-care equipment is typically powered by two-stroke engines. They are cheap, compact, lightweight, and simple. They are also highly polluting, generating up to 5 percent of the country’s air pollution, according to the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA).

Each weekend for much of the year, according to estimates, some 54 million Americans mow their lawns. All this weekend grass cutting uses some 800 million gallons of gasoline annually. That doesn’t include the gas used to trim around trees and fences and to blow grass clippings around.

Those 800 million gallons also don’t include the gas used for lawns mowed during the week or by landscaping companies. It doesn’t include the oil that is also burned by these cheap engines. It doesn’t include grass cut on golf courses and along median strips and other public spaces covered by green carpets devoid of diversity.

A 2011 study showed that a leaf blower emits nearly 300 times the amount of air pollutants as a pickup. The EPA has estimated that lawn care produces 13 billion pounds of toxic pollutants annually.

This equipment is also noisy. Leaf blowers emit between 80 and 85 decibels, but cheap or mid-range ones can emit up to 112 decibels. Lawn mowers range from 82 to 90 decibels. Weed whackers can emit up 96 decibels of noise.

Electric lawn equipment is gaining in popularity and will slowly lessen the amount of fossil fuels burned to cut millions of acres of grass — a 2005 study found that about 40 million acres in the continental United States has some form of lawn on it. Electric equipment is also quieter than its gas-powered counterparts.

Much of the 90 million pounds or so of fertilizer dumped on lawns annually are fossil-fuel products. Nitrogen fertilizer, for instance, is made primarily from methane.

As stormwater carrying nitrogen and phosphorus from fertilizer runs off into streams and rivers and eventually into larger waterbodies such as Narragansett Bay, it impacts ecosystems and fuels algal blooms, some toxic, that suck oxygen from water.

On Rhode Island’s Aquidneck Island, for example, stormwater runoff carrying these nutrients is stressing coastal waters and contaminating the reservoirs that feed the Newport Water System.

The amount of toxic chemicals applied to lawns and public grounds annually to jolt grass to life and kill pests is staggering. This copious amount of poison, about 80 million pounds annually, is marked by white and yellow flags warning us not to let children or pets onto these monolithic spaces whose appearance trumps their health and that of the surrounding environment.

These warning flags are planted because of the 30 commonly used lawn pesticides 17 are probable or possible carcinogens; 11 are linked to birth defects; 19 to reproductive impacts; 24 to liver or kidney damage; 14 possess neurotoxicity; and 18 cause disruption of the endocrine (hormonal) system. Another 16 are toxic to birds; 24 are toxic to aquatic life; and 11 are deadly to bees.

Of course, these poisons don’t just kill or harm their intended targets.

While these chemicals hang around “feeding your lawn” or killing life, they are breaking down and working their way into the environment — until another application is applied, sometimes just a few weeks later, and the cycle repeats.

Poisons from these artificial fertilizers and the various -cides applied to lawns can seep into groundwater — contaminating drinking-water supplies — or turn to dust and ride the wind. They cling to people and pets who walk, run, and lie on treated grass. They get kicked up during youth sporting events.

These chemicals can be inhaled like pollen or fine particulates, causing nausea, coughing, headaches, and shortness of breath. For asthmatic kids, they can trigger coughing fits and asthma attacks.

Two of the most common pesticides, glyphosate used in Roundup and 2,4-dichlorophenoxyacetic acid (2,4-D) in Weed B Gon Max, have been linked to a number of health issues, including developmental disorders and cancer. The latter is a neurotoxicant that contains half the ingredients in Agent Orange, according to Beyond Pesticides, a Washington, D.C.-based nonprofit.

The Natural Resources Defense Council (NRDC) has called 2,4-D “the most dangerous pesticide you've never heard of.”

Developed by Dow Chemical in the 1940s, the NRDC says this herbicide helped usher in the green, pristine lawns of postwar America, ridding backyards of vilified dandelion and white clover.

Researchers have observed apparent links between exposure to 2,4-D and non-Hodgkin's lymphoma and sarcoma, a soft-tissue cancer, according to the NRDC. It notes, however, that both of these cancers can be caused by a number of chemicals, including dioxin, which was frequently mixed into formulations of 2,4-D until the mid-1990s.

In 2015, the International Agency for Research on Cancer declared 2,4-D a possible human carcinogen.

Last year Bayer paid nearly $11 billion to settle a lawsuit over subsidiary Monsanto’s weedkiller Roundup, which has faced numerous lawsuits over claims it causes cancer.

Lawns are one of the most grown crops in the United States, but unless you are a goat or a dog with an upset stomach their nutritional value is zero. Yet the collective we continues to spend about $36 billion a year on lawn care.

Instead of putting public health at risk and degrading the environment with a chemically treated lawn, create a yard with a diverse mix of native trees, shrubs, and plants; it is cheaper to maintain, easier to take care of, environmentally beneficial, and more interesting.

Native plants support native wildlife and insects, are accustomed to the weather and soil, and are pest resistant. They support the pollinators of our food crops, clean the air and water, and help regulate the climate. They also make good natural buffers, which capture rainfall and filter stormwater runoff.

Frank Carini is editor of ecoRI News.

The first gasoline-powered lawn mower, 1902

Trying to save Aquidneck Island's open space

Windmill (built around 1810) at Prescott Farm, in Middletown, R.I.., on Aquidneck Island, which still has some countryside, or at least rural-looking exurbia.

From Robert Whitcomb’s “Digital Diary,’’ in GoLocal24.com

‘EcoRI News’s Frank Carini had a good story on Aug. 18 about how Aquidneck Island could run out of its currently unprotected open space by 2050, and not because of a big increase in population but because of sprawl development, whose ugliness is all too apparent on the roads leading to Newport. This still unbuilt-on space includes farmland (vineyards, sweet corn, etc.), woods and other open space. There’s still considerable inland natural beauty left on the island that many tourists who head for, say, Newport’s spectacular Ocean Drive don’t notice.

How to protect the island’s remaining natural beauty? Encourage zoning changes that favor housing density and compact commercial development instead of housing subdivisions and malls, strip or otherwise. (Presumably the continuing rise of Internet shopping will continue to undermine the business model of malls, with their asphalt parking lot acreage mostly empty and wasted when the stores are closed and whose hard surfaces add to local flooding and water pollution.)

Also needed is a much, much denser public transportation network that would reduce car dependence and the sprawl it fosters.

Remembering that Aquideck is an island, albeit a big one by Northeast standards, should remind people of its fragility. To read Mr. Carini’s piece, which includes graphics, please hit this link.

Frank Carini: Restoration plan for species hurt by 2003 Buzzards Bay oil spill

Common Loon

From ecoRI News (ecori.org)

State and federal environmental agencies have released a draft plan to help common loons and other birds in the wake of the 2003 Bouchard Barge No. 120 oil spill in Buzzards Bay, in both Rhode Island and Massachusetts waters.

The draft plan is available for public comment through Oct. 31. Written comments can be sent via email to molly_sperduto@fws.gov. The agencies are scheduled to hold an information meeting and webinar Sept. 12 at 1 p.m. at the Massachusetts Division of Fisheries and Wildlife office at 1 Rabbit Hill Rd, Westboro.

The plan is the first of two documents to address birds injured by the spill, both of which will be funded by a 2017 $13.3 million natural resource damages settlement from Bouchard Transportation Co. Inc. Of this total, $7.3 million is designated to plan, implement, oversee and monitor common loon restoration, while another $1 million will go toward other birds impacted by the spill. Another $5 million from the settlement will address injuries to common and roseate terns through a separate future plan

This plan describes the injuries resulting from the 98,000-gallon spill that oiled 100 miles of shoreline, including coastal habitats where birds feed, nest, and in some cases overwinter. An estimated 531 common loons and more than 500 other birds, including common eiders, black scoters, red-throated loons, grebes, cormorants, and gulls, were killed either through direct or indirect effects of the spill.

Common loons winter in large numbers in Buzzards Bay. Common eiders experienced the highest mortality of all other bird species, with 83 birds killed by the oiling. The ultimate goal of the damage assessment and restoration process is to replace, rehabilitate, or acquire the equivalent of injured natural resources and resource services lost because of the release of hazardous substances, at no cost to taxpayers.

“The trustees have carefully considered a number of options to restore birds killed by the 2003 oil spill, especially the common loons that are icons of our northern lakes,” said Tom Chapman, supervisor of the U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service’s New England office. “We invite people to learn about and provide feedback on these ideas, in hopes of soon starting restoration efforts benefiting birds throughout New England.”

The draft plan evaluates multiple restoration alternatives that were developed in coordination with loon and other bird experts. Based on factors to ensure successful restoration, as well as criteria established by federal regulations, the trustees recommend the following projects:

Release 63-84 common loon chicks from Maine and New York in historic Massachusetts breeding sites in Assawompset Pond Complex and the October Mountain Reservoir, in hopes of returning this species to more areas in the state ($3,185,000). In Massachusetts, common loons disappeared for decades until 1975, and have since primarily returned to breed in Quabbin and Wachusetts reservoirs, migrating offshore to winter.

Increase survival of nesting loons at breeding sites across New England ($3,185,000) through: creating artificial nesting sites on rafts that withstand fluctuating water levels and reduce disturbance from predators and people; adding signs and wardens to watch over nests to reduce disturbance; preserving land to protect breeding habitat; and reducing exposure to lead tackle through outreach and tackle exchange programs

The trustees’ preferred alternatives to restore other bird species are:

Permanently protect more than 300 acres of high-quality coastal habitats on Cuttyhunk Island off the coast of Massachusetts ($500,000).

Identify a similar habitat protection project in Rhode Island through a competitive grant process ($1,274,000)

Use signage, nest monitoring, and wardens to protect common eider nests in the Boston Harbor Islands and Cuttyhunk Island ($100,000).

Frank Carini is editor of ecoRI News.

Frank Carini: Time for municipal renewable-energy-based utilities?

Via ecoRI News (ecori.org)

More than a decade ago, Rock Port, a small farming community in northwest Missouri, reportedly became the first U.S. municipality to be powered almost exclusively by renewable energy. Four large wind turbines are connected to the power grid and provide the town’s nearly 1,400 residents with most of the power they need. The turbines produce about 16 million kilowatt-hours of electricity annually.

When the wind isn’t blowing, residents buy power from the grid. But on most days, the turbines generate enough wind power for the town to get paid to export energy.

Members of the Rhode Island Progressive Democrats of America are hoping to create a similar energy situation in Cranston. The group is raising money to have a study done to determine if a municipal renewable-energy utility would work in Rhode Island’s second-largest city.

The group’s broader idea is to create an energy plan that would transform the Ocean State into a sizable producer of solar, tidal, and onshore wind power. The group’s aim is to generate 200 percent of the power that the state needs and to return energy profits to Rhode Island as citizen dividends and municipal funding.

ecoRI News recently spoke with Nate Carpenter, the group’s state coordinator, and Wil Gregersen, its environmental co-coordinator, about Rhode Island’s renewable-energy potential and its ability to address climate change. While they admitted that the project, which is in its infancy stage, is ambitious, they also noted that it’s an excellent way to fight climate change.

Gregersen said the idea is to “build a pressure from underneath” to move legislators to address the issue.

“We really want to sell this to every person who lives here,” he said. “We know that all the pieces for doing this kind of thing exist … renewable-energy technology, models for setting up a municipal utility, all these pieces are out there they just need to be assembled.”

“We want to make switching to renewable energy an attractive offer,” Carpenter added. “We want to incentivize people to make this change.”

Rhode Island currently spends about $3 billion annually on energy, most of it from outside sources and most of it from fossil fuels. As an energy producer, Gregersen said, Rhode Island could keep that money in the local economy.

The Rhode Island chapter of the Progressive Democrats of America are partnering with Ocean State Community Energy, a collaborative of Massachusetts-based ReVenture Investments and 4E Energy, to develop a plan to build municipal utilities across Rhode Island, starting with a scalable design for a utility in Cranston. The design will use existing city infrastructure, will avoid green space, and will employ the latest innovations in renewable technology, they said.

With a well-researched plan that shows what such a utility would look like and how it would work, Gregersen and Carpenter say they will be able to start large-scale fundraising for a statewide plan and to advocate for similar projects across Rhode Island. The idea is strong, but they noted proof of concept is needed before any additional steps can be taken. The study will cost $26,000.

Gregersen said the study will determine how much renewable energy Cranston could produce and the amount of profit that could be generated. He said Cranston is a good model, because it has both urban and suburban areas.

“Rhode Island, the Blackstone valley, was the site of the Industrial Revolution and this was an incredibly powerful and wealthy place,” Gregersen said. “We’d like to do that again for our state by creating an energy revolution.”

Both Gregersen and Carpenter noted that they are disheartened by the time and effort that has been wasted dealing ineffectively with climate change. They said the issue needs to be addressed immediately. To address the ongoing lack of urgency, Carpenter said the Rhode Island Progressive Democrats of America has elevated addressing climate change/reducing fossil-fuel emissions as its core issue. He noted that worsening climate events will overstretch vulnerable communities and tear societies apart.

“We see with absolute clarity that if we don’t solve climate change we won’t solve anything we care about,” he said. “Everything that progressives are fighting for will come to nothing if climate change is allowed to continue. We’re not here to scare people. These things are real but we do have the ability to fix this, or at least mitigate the effects of climate change.”

Frank Carini is editor of ecoRI News.

Frank Carini: Microplastic pollution imperils corals

A recent study found that northern star coral polyps routinely consumed microplastics, shown above in blue, over brine shrimp eggs, shown in yellow.

— Photo by Rotjan Marine Ecology Lab at Boston University

From ecoRI News

Coral reefs form the most biodiverse habitats in the ocean, and their health is essential to the survival of thousands of other marine species. Unfortunately, these vital underwater ecosystems are beginning to get a taste for plastic.

A Roger Williams University professor, working with a team of researchers, recently published a study that found corals will choose to eat plastic over natural food sources. Unsurprisingly, it’s not good for their health, as it can lead to illness and death from pathogenic microbes attached to microscopic plastics. It also adds to the stress already being applied to coral reefs worldwide, by acidifying and warming oceans, other pollution sources, development, and harmful fishing practices, such as dynamiting and bleaching to capture fish for aquariums.

The project grew from concern about the 6,350 million to 245,000 million metric tons of plastic in the world’s oceans, and the 4.8 million to 12.7 million metric tons of new plastic that enter annually.

Photographs and news reports have documented dead whales and seabirds found with stomachs full of plastic and of sea turtles suffocating from plastic straws clogging their nostrils. At least two-thirds of the world’s fish stocks are suffering from plastic ingestion, according to estimates, as much of the planet’s plastic pollution eventually makes its way into the ocean.

Roger Williams University associate professor of marine biology Koty Sharp recently told ecoRI News that plastic pollution presents a growing problem for both water- and land-based ecosystems.

“It’s a huge problem,” she said. “There’s really nowhere left on the planet that hasn’t been touched by plastics. We’re finding plastics in every organism we study.”

As much as plastic proliferation is a problem, Sharp is even more concerned about the impacts of a changing climate and how humans are using natural resources. She pointed to the manmade damage being done to Australia’s Great Barrier Reef as an example.

“We need to quickly and dramatically decrease our dependency on plastics and fossil fuels,” the microbiologist said. “This isn’t a problem a few people can fix.”

The study that Sharp helped author was published recently in London’s science journal, Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences. It is the first of its kind to identify that corals inhabiting the East Coast of the United States are “consuming a staggering amount of microplastics,” which alters their feeding behavior and has the potential to deliver fatal pathogenic bacteria.

In their samples of northern star coral, collected off the coast of Jamestown, R.I., each coral polyp — about the size of a pin head — contained more than 100 particles of microplastics, according to the collaborative research team that included Sharp, Randi Rotjan, a research assistant professor of biology at Boston University, and colleagues from UMass Boston, Boston Children’s Hospital Division of Gastroenterology, Harvard Medical School, and the New England Aquarium.

Northern star coral can be found from Buzzards Bay to the Gulf of Mexico. Since it can be found along the coast of most East Coast urban areas, Sharp said it is a “powerful tool” in helping to understand microplastic pollution.

Although this study is the first to document microplastics in wild corals, previous research had found that this same coral species consumed plastic in a laboratory setting. A 2018 study found plastic pollution can promote microbial colonization by pathogens implicated in outbreaks of disease in the ocean.

The study co-authored by Rotjan and Sharp produced similar lab results. When the researchers conducted experiments of feeding microbeads to the corals in their labs, Sharp said they found that the coral would more often choose the fossil-fuel derivative when given the choice between plastic and food of similar sizes and shapes, such as brine shrimp eggs.

In fact, every single polyp, or mouth, that was given the choice ate almost twice as many microbeads as brine shrimp eggs. After the polyps had filled their stomachs with plastic junk food with no nutritional value, they stopped eating the shrimp eggs altogether.

The study showed that bacteria can “ride in” on the microbeads. In the case of the bacteria they used in the lab — the intestinal bacterium E. coli — the microplastic-delivered bacteria killed the polyps that ingested them and their neighboring polyps within weeks, even though the polyps spit the microbeads out after about 48 hours. The E. coli bacterium persisted inside their digestive cavity.

“Research has shown that there are virtually no marine habitats that are untouched by plastics,” said Sharp, noting that research abounds demonstrating that nearly all ocean water contains plastic pollution. “Because of that, it’s critical that we understand the impact of plastics pollution. Microplastics pollution is a matter of global health — ecosystem health and human health.”

She noted that the problem of plastic pollution extends far beyond what can be seen. Plastics never fully degrade in seawater, breaking down into smaller and smaller pieces. Invisible to the naked eye, microplastics remain suspended in the water column, and this is what corals and other filter-feeding animals take in to get their food, she said.

The researchers had anticipated they would find microplastics in wild corals, but they were shocked by the volume present in their samples, according to Sharp.

Another invisible factor is the presence of microbes that hitch rides with plastics floating in the ocean, winding up in the stomachs of many creatures. These plastic-riding microbes are growing in number and upending the delicate balance of ecosystems.

Sharp said the problem is being made worse by human-induced climate change, which is helping bacteria to proliferate. She noted that microplastics in the ocean are coated with microbes.

“We know that plastic particles provide an enriching habitat for bacteria that are not usually in very high numbers in seawater,” Sharp said. “The microbial aspect of microplastics pollution is largely underexplored — it’s critical that we learn more about how plastics can affect the dynamics, abundance, and transport of microbes through our ecosystems and food webs. Alteration of microbiomes in our marine ecosystems by human-induced threats like plastics pollution and climate change holds great potential to impact marine environments on a global scale.”

To help mitigate the problem of plastic pollution, Sharp offered some tips:

Minimize single-use plastics. Use reusable bags and mugs. Buy groceries in bulk. Decline a straw if you don’t need one.

Take a day to count. How many times in one day do you use single-use plastics. What is unnecessary and what can be eliminated or replaced with more sustainable products?

Demand lower-impact packaging and support products with sustainable packaging.

Support and advocate for legislation and lawmakers that promote innovative solutions and alternatives for sustainable packaging.

“Given that plastics pollution is an ongoing threat co-occurring with climate change, it’s critical that we do more research to understand how they impact marine ecosystems together,” Sharp said, “and take immediate actions to minimize human impacts on the world’s oceans.”

Frank Carini is editor of ecoRI News.