Hilary Cosell: My father's friendship with Muhammad Ali and their fight for justice

“I’m gonna kill you, nigger-loving Jew bastard.”

The so-called Jew bastard was my late father, the broadcast sports journalist Howard Cosell, and the quote typical of the hate mail that poured into his office from the moment in 1964 that he said, “If your name is Muhammad Ali, I will call you Muhammad Ali.”

Muhammad’s death on June 3 was a bit like my father dying a second time, because as long as Ali was alive, a piece of my father still lived. Together they represented the very best that this country has to offer, and exposed the worst, too.

As the Ali accolades poured in, and his status as a national treasure remained firmly in place, as I watched and listened to the round-the-clock tributes, I thought back to those years between 1964 and 1971, during which Ali was stripped of his title, the years he lost in boxing, and the hatred that engulfed him. I wondered how many people lauding him now even remember those days, or the true reasons why he deserved such praise.

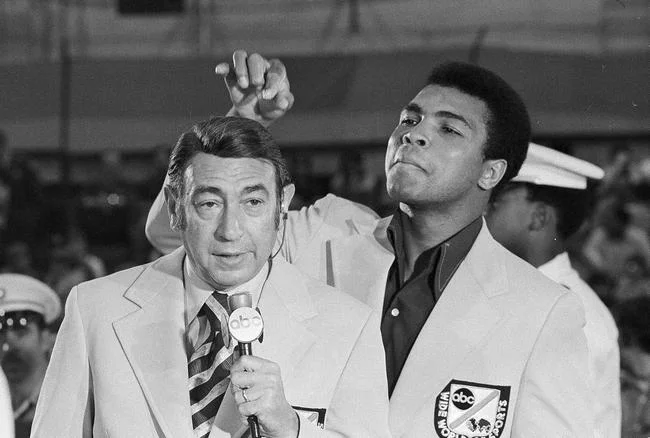

My dad covered boxing for ABC, and so he began to cover Ali. Right from the start they had the kind of rapport that often develops between two smart, fast-talking people. On camera together their relationship was entertaining, and they became synonymous in people’s minds: Ali-Cosell, Cosell-Ali.

But there was a bond between them that had nothing to do with repartee. It was forged during those years of the Freedom Summer, of riots and cities burning in the summer of 1965, the Gulf of Tonkin resolution, the draft, and the Vietnam War, and the Black Power Movement.

My father stood alone and stood his ground when he used Muhammad’s name. Sportswriters and broadcasters refused to speak it, and The New York Times wouldn’t print it. Other boxers continued to use it, and paid for it in the ring.

In 1966 Ali was reclassified as 1A by his draft board, and in 1967 he refused to step forward, and applied for conscientious objector status on religious grounds.

He was stripped of his title, stripped of the right to box professionally, his passport was lifted, and many Americans despised him.

He was called an ingrate, a coward, uppity, someone who didn’t know his place, a traitor, and accused of treason. What made his decision even worse, if possible, was the that he had joined a separatist black Muslim “nation” founded by Malcolm X. (He later left it and practiced a different form of Islam.) It’s no exaggeration to say that he was white America’s nightmare: a young, strong, articulate, separatist black man who said, “No Vietcong ever called me nigger.”

Alone again, my father rose to Ali’s defense. Howard Cosell was a lawyer and knew what was at stake immediately. This had nothing to do with boxing. At issue were freedom of speech, freedom of religion, equal protection and due process.

Amidst the hysteria and hate, my father explained the law, and Ali’s rights, over and over again. Few listened.

When Ali couldn’t box, my dad periodically interviewed him on ABC’s Wide World of Sports, and used him as a commentator on fights. He kept his name, face and case before the public.

One of my favorite stories about them took place at a classic, elegant New York restaurant, called Café des Artistes. It was a hangout for ABC, because the network’s headquarters was directly across the street.

It was a Saturday, lunchtime, and my mother and I got a table and ordered lunch, while my father did an interview with Ali. Suddenly there was a commotion at the entrance and my father strolled in with Ali and his entourage.

“Look who I brought to see you, Em,” he said to my mother, Emmy.

The maître d’ was used to my dad showing up with unexpected people. Tables were quickly pushed together, and Muhammad and friends sat down to eat. I looked around the restaurant, which was fairly crowded with a lily-white clientele who fell silent when Ali arrived, and simply stared. We ignored them.

After they had eaten and left, an older white gentleman cautiously approached our table and asked if he could speak with my father. He nodded.

“Why did you bring him here, Mr. Cosell? He doesn’t belong here. We’re afraid of him. Aren’t you?”

My father looked at the man and quietly replied, “With all due respect, sir, the only thing I’m afraid of are the sentiments you just expressed.” My father then said, “If you’ll excuse me, I’m lunching with my family.” The man scurried away.

Some revisionist historians write that Muhammad and my father were never friends, and that my father hooked on to Ali to further his career, not out of any sense of justice. It’s true that they helped each other’s careers along the way. But Howard Cosell’s defense of Ali defined my father’s career, as well as his character, conscience and courage -- and defined a bond of trust between two unlikely men that would never be broken.

Hilary Cosell is a Connecticut-based writer anda former NBC sports journalist and an occasional contributor to New England Diary.