Robert Whitcomb: Reporting in pre-glitz Boston

Soon after I had graduated from college, in June 1970, a friend suggested that I try to get a job at the Boston Herald Traveler (RIP), an old Yankee establishment newspaper that also had a lucrative TV and radio station. I applied, but first, the city editor, the always unflappable and wry Bob Kierstead, said that I should report and write a research project -- a little book -- for the paper to prove I could report. The book, on Boston politics, history and demographics, was meant to help the paper’s reporters cover the next mayoral and other local elections.

Mr. Kierstead found the little book useful enough to hire me a reporter. I wish that I could find what I wrote and compare the reporting in it with the very different (much glitzier and more Manhattanish) Boston of today. Back then, Boston had a down-at-the-heels quality that evoked the Thirties, or even Dickens’s London.

Then began a crazy year of covering all kinds of stuff – from train derailments, murders, industrial-strength arson, potheads lost in the White Mountains, race and student riots, the start of Boston’s busing/desegregation crisis and the opening of Walt Disney World. It was one of my most vivid periods and showed me what I could do on deadline and often in considerable chaos on the road.

I thought that it would be just an occupational side trip, whence I would return to school to perhaps get a doctorate in history or start a small business. But I found I had a talent for quickly if roughly understanding people, places and situations and concisely writing down fast what I had so quickly learned. What’s more, back then, I liked to travel (much more than now). Journalism spoke to these things. A college history major, I looked on my work as writing current history. Or, as the late editor of The Washington Post, Ben Bradlee, put it, “history on the run.’’

But I knew I couldn’t stay at the Herald Traveler because it was likely soon to lose its FCC license for its very profitable TV station, which, with its sister radio station, had been subsidizing the newspaper. The case went up to the U.S. Supreme Court, where the owners lost for good; the paper's assets were sold shortly thereafter to Hearst, for whose sensationalist Boston tabloid, the Record American, I had worked in a summer job as an editorial assistant/gofer.

So I applied to the Columbia University Graduate School of Journalism, was admitted, got an economics fellowship and off I went, at the end of the summer of 1971, to New York. This was just after the Pentagon Papers were printed and Nixon took America off the gold standard. The latter led me to interview for the Herald Traveler a covey of famous economists, most notably Milton Friedman and John Kenneth Galbraith, shortly before I left for Manhattan.

It was fun to have such access to celebrities.

And it was a relief to leave the stuffy walkup apartment I was renting on the Cambridge-Somerville line from the brother of a former girlfriend.

Robert Whitcomb is editor of New England Diary.

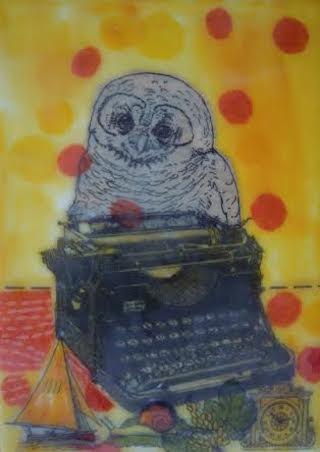

Returns of the day with coffee and doughnuts

"The Pundit'' (mixed-media encaustic), by NANCY WHITCOMB

I have many vivid memories of Election Days. First, there were those jolly little Eisenhower-for-President parades in '52 and '56 in the overwhelming Republican town I lived in. Then there was anxiously watching very late into the night the dubious election of 1960 as returns were dragged from (and invented in) Illinois and Texas to hand the victory to Kennedy. My mother, who was, well, crazy, was so angry about the outcome that she tried to throw the heavy new "portable'' TV on which she had watched the returns out the window but was restrained.

After Kennedy took office, my mother developed a weird romantic (erotic?) attachment to the Kennedys and was devastated about the murders of John and Robert -- events that my calm father responded to with remarkable, even eerie equanimity, even for him.

I remember Nixon's graciousness on TV about his defeat, though of course his resentments continued to simmer.

Then there was the dubious presidential election of 2000, with the Republicans taking that brass ring via Florida machinations and the U.S. Supremes, though it took weeks to be sure who officially "won''. To this day, who knows who really got more votes in Florida -- Gore or G.W. Bush? By that time I was too tired of politics to stay up most of the night watching the show, which I had done for decades, mostly because it was (sort of) part of my job.

But one election I remember with great pleasure. In November 1970 the old Boston Herald Traveler sent me to Pittsfield , Mass., to get the election returns from Berkshire County. It wasn't a presidential-election year but there was plenty of excitement about close New England races.

I had no idea how to go about getting the tallies in t. No one on in Boston gave me any guidance. "Bobby, just get them to us as soon as you can,'' was the directive from the city editor. In other words, be inventive. It was a test of my skills in the face of inexperience.

And not only did the paper urgently need the returns as soon as they were official but, even more urgently, the TV and radio stations they owned did. They were updating about every 15 minutes!

But I didn't have a clue. I first thought that maybe I should go to Pittsfield City Hall and some old Board of Canvassers guy could help me out. Or maybe the headquarters of Silvio Conte, the GOP congressman from western Massachusetts. As I wandered, increasingly anxious, down the streets of this mill town/county seat, (General Electric virtually owned it) on that wan November afternoon, I came across a radio station.

Maybe someone there could help me. This was before the huge radio-station chains took away most of the local sounds (including accents) you used to get on your local radio station, replacing them with national call-in blowhards, infomercials and other canned stuff. In the old days, most of the dominant small-city radio stations had at least one or two local news people and a news announcer with a nice baritone. (He might moonlight as the "Music in the Night'' announcer. Percy Faith and his Orchestra.)

I went into the station and sat down in the waiting room. Some middle-aged guy wearing a tattered tweed jacket came out and asked me what I wanted. "I have no idea what I'm doing. How do I collect all these votes?'' I said apologetically.

He asked me if I knew anyone around there. Well, yes, -- Frank Strom, an uncle of mine by marriage who had run the big local bank. (He later moved to Providence and did a fine job running the Old Stone Bank (RIP, both of them).

"A great man!,'' he said, noting that my uncle had provided ''half this town with mortgages.''

"We'll take care of you,'' he promised. Then a secretary brought me a doughnut and a cup of coffee and directed me to a phone in the corner. There I camped out for most of night as they brought me sheets of paper with returns scrawled in them (collected by one of the station's newsmen) to call in to the grumpy rewritemen in Boston. The station had "runners'' from all over that hilly county calling in votes.)

From time to time the station manager would relate some tales of local politicians, informed by cynicism and idealism, dislike and affection. I never quite figured out his political affiliation, if he had any.

The tough customers at the Herald Traveler were impressed with my speed and efficiency. I had a very pleasant drive back to the office the next day; the Massachusetts Turnpike had never looked lovelier. Of course I never told them how I got those golden returns.

Their 2 major food groups: Nicotine and alcohol

''Beer and Cigarette'' (oil on plexy), by MICHAEL DOYLE, at Patricia Ladd Carega Gallery, in Center Sandwich, N.H.

It wasn't that long ago that millions of workers daily repaired after their shifts to smoky joints like the one that this picture recalls. These places were very close to offices or factories. Indeed, the bars were often scientifically located specifically to serve this or that local big company.

Employees could chain-smoke simply by breathing in the air of the bar. For hours, they'd drink and do supplemental smoking. Then, especially if it were late in the week, repeat the process all over again the next day. Now folks can't smoke in bars, which reduces the desire for drink, which reduces the desire to smoke. (The big exception: The giant bars known as casinos, where state taxing authorities, and income-and-sales-tax-hating citizens, want the cross-promotional addictions of booze, cigarettes and gambling to keep pumping up state budgets from states' draw on casino revenues.)

For that matter, plenty of people went to bars on their "lunch break,'' and unless they were falling down drunk when they returned to the offices or factory, it was tolerated -- indeed, expected. Executives did it, too, albeit more likely ordering cocktails and bottles of wine than what their lackeys bought, which was mostly (bad) beer.

About half the news desk staff at the old Boston Herald Traveler, where I worked, would go next door to a joint called Foley's and toss back a few at their "lunch,'' which came at mid-evening. (It was a morning paper so the paper was mostly produced between about 6 p.m. and 2 a.m.).

The daily heavy-drinking habit, along with relentless deadlines, rapidly aged the editors. Many of those who I thought were around 60 were in fact about 40. But many were addicted to the daily adrenaline of deadines and breaking news (much of which was suffused with false urgency).

All in all, a lousy way to live, but we all got stories about at least mild depravity out of it. Some of us even still remember them.

--- Robert Whitcomb