James Dempsey: In the heyday of Modernism, a memorably snippy writer-editor back-and-forth; photo correction

Alyse Gregory

Maxwell Budenheim (1891-1954)

CORRECTION: Due to an editor’s error, we misidentified a photo that had previously run with this piece as being that of Alyse Gregory. It was of Gamel Woolsey. We regret the error.

James Dempsey is the Worcester area-based author of The Court Poetry of Chaucer, Zakary’s Zombies, Murphy’s American Dream and The Tortured Life of Scofield Thayer. Research for the last is the basis of this essay. Mr. Dempsey has also served as a newspaper columnist, editor and teacher.

Maxwell Bodenheim and Alyse Gregory are two of the lesser-known names from the Modernist period. Bodenheim is undoubtedly the more notorious, thanks to a career that in the 1920s soared with exceptional promise but which, after Bodenheim’s life descended into addiction and crashing poverty, came to an end in the horrific 1954 double murder of himself and his wife, then homeless, at the hands of an unstable dishwasher they had befriended. Bodenheim was a writer of great facility who could turn his pen to poetry, fiction, and criticism, producing some two dozen books, as well as the mountain of bread-and-butter literary journalism required of the freelance writer.

Gregory was a singer, a suffragist, and a writer. The owners of the magazine The Dial, Scofield Thayer and J. Sibley Watson, urged on her the post of Managing Editor of the journal after Gilbert Seldes left the position to write what would be his most famous book, The Seven Lively Arts. She politely rebuffed them several times, not comfortable with being entrusted with so much power in the literary world of 1920’s New York City and less than confident that she could meet the magazine’s high standards.

Thayer and Watson had bought The Dial in 1919 and made of it an arts and literary magazine that attracted both avant-garde and established writers and artists. It was successful by every measure except profitability--one year it lost today’s equivalent of $1.5 million—but this was just a minor irritant to the owners, who owners, who were heirs to great wealth, Thayer to a New England textile fortune and Watson to the Western Union empire. Pay rates were generous and assured, the magazine was beautifully designed and brilliantly curated, and consequently writers and artists were eager for their work to appear in its pages. Thayer and Watson both greatly admired Gregory, and when they made made an unannounced joint appearance in her Greenwich Village apartment to importune her to edit the magazine, she finally succumbed to the pressure. She was named Managing Editor in Februry 1924 would remain at The Dial until moving with her husband, novelist Llewellyn Powys, to England the following year. During her tenure the magazine accepted work from E.E. Cummings, T.S. Eliot, D.H Lawrence, Thomas Mann, Marianne Moore, Llewelyn and T.S. Powys, Siegfried Sassoon, Bertrand Russell, Wallace Stevens, Edmund Wilson, Virginia Woolf, a nd W. B. Yeats. Artists whose work appeared included Mac Chagall, Georgia O’Keeffe, Henri Matisse, Edvard Munch, Pablo Picasso, Auguste Rodin, and John Singer Sargent

Bodenheim was well-represented in The Dial. Seven of his poems appeared in the February 1920 issue, the second under its new owners. The magazine went on to publish Bodenheim’s verse in the August 1921, March 1922, and April 1923 issues. He also published a short story in December 1921 and wrote a review of Ezra Pound’s Poems int the January 1922 issue.

Bodenheim’s own work was given two full-length reviews in the journal. In October 1922 Malcom Cowley reviewed his book of verse, Introducing Irony. Cowley sounded a touch baffled: “He writes English as if remembering some learned book of Confucian precepts.” At one point he said that Bodenheim’s “accumulation of images resembles Shakespeare,” although the reader is not sure from the context if this is intended wholly as a compliment (Bodenheim certainly took it as such). Bodenheim, Cowley wrote, is the “American prophet of the new preciosity (and with many disciples).” The critic sums up Bodenheim’s verse as “stilted, conventional to its own conventions, and formally bandaged in red tape.” He accused its author as having “all the insufferability of genius, and a very little of the genius which alone can justify it.”

In September 1924 Marianne Moore produced a long and nuanced survey of Bodenheim’s work to date with a focus on his poetry collection Against This Age and his novel Crazy Man. Moore grants Bodenheim a wide popularity but notes that “one is forced in certain instances to conclude that he is self-deceived or willingly a charlatan.” She distrusts his “concept of woman” and Bodenheim’s pronouncement “that there is zest in bagging a woman who is one’s equal in wits” is punctured by her remarking that “the possibility of bagging a superior in wits not being allowed to confuse the issue.”

Moore goes on, however, to find more than occasional felicities in Bodenheim, such as the line, “simplicity demands one gesture and men give it endless thousands.” In his stories she finds a “genuine narrator” and “an acid penetration which recalls James Joyce’s Dubliners.”

Bodenheim’s books also showed up in the magazine’s “Briefer Mention” thumbnail reviews in June and August 1923, January 1926, and August 1927.

All in all, this is a better-than-average showing in a magazine whose Contents page was populated by writers who would go on to comprise much of the 20th Century’s Western literary and artistic canon, the high priests and priestesses of Modernism.

One notes from the publication dates of Bodenheim’s work in The Dial that his writing is absent in 1924 and 1925, a period that happens to correlate with Gregory’s tenure at the magazine. This was not a coincidence. Try as he might, Bodenheim was unable to get Gregory to accept even one of his pieces. There appears to be nothing sinister about her rejection of his work; she simply did not care for it and wondered what others saw in it. She did realize, however, that Bodenheim had his admirers, and it was she who persuaded Scofield Thayer to run the review by Marianne Moore mentioned above. “I always knew you disapproved of my asking Marianne Moore to do a review of Maxwell Bodenheim’s books,” she wrote Thayer apologetically. “He is so very much a figure among certain people … that I thought he should be exposed if nothing else.”

If Bodenheim couldn’t win Gregory over, it wasn’t for want of trying. Their correspondence shows Bodenheim continually advancing on her like a big-hearted prize fighter being peppered by punches from a more technically gifted pugilist, and continuing to limply jab until he finally realizes the match is unwinnable, slumps into his corner stool, and mumbles, “No mas.”

He made his first submission, a single poem, soon after Gregory had taken up the post. She returned it, with the note below, and so set in motion an epistolary exchange that even though a century old will be familiar to both writers and editors of all ages, the one side so desperate to get the work out before the public, the other side overworked and inundated and trying not to be hardened by a job that mostly consists of rejecting.

And of course, the reality is that, unless the writer has reached a certain level in the pyramid of success, all the power is on the side of the editor. Even the word “submission’’ betrays the essential asymmetry of the relationship.

---

January 15, 1924

My dear Mr. Bodenheim,

It is very painful indeed to return a poem of yours, especially if one has been and is so very definite an admirer of your work. This one we do not wholly like, however, and so we endure the pain.

Very sincerely yours,

Alyse Gregory,

Managing Editor

January 15

My dear Miss Gregory,

“It is very painful indeed to return a poem of yours, especially if one has been and is so very definite an admirer of your work. This one we do not wholly like, however, and so we endure the pain.”

Your note to me, quoted above, rouses me to a new and sad unfolding of thought. During the last two years The Dial has accepted only one poem out of sixty submitted for approval. In fact, every poem in my last two books of verse have experienced the honor or misfortune of being refused by The Dial .... If it was so very painful for the editors to return these poems, I must for the first time sympathize with their predicament, although it would seem their capacity for enduring pain has been unlimited in my case. Still, I do not like to know people have suffered with my unconscious assistance, and I am tempted to send letters of condolence to Mr. Thayer, Mr. Watson, and Mr. Burke [Kenneth Burke, an assistant editor]. However, since The Dial has published during the past two years numerous poems by E.E. Cummings. William Carlos Williams, Marianne Moore, and Alfred Kreymborg, the editors of The Dial must have relieved their pain with contrasting moments of happiness. The Dial has also printed derogatory reviews of my last three books, in one of which I was accused of imitating William Shakespeare (!), and they have not seemed to indicate a very definite admiration on the part of the editors who allowed them to appear.

You must understand that this hopeless and justified sarcasm is not in any way directed at yourself. I do not know you and have no reason to doubt the sincerity of your statements. It may be indeed that you are actually a very definite admirer of my work, and I shall be happy to add you to my small band of critical friends. It is obvious, of course, that I am not a member of the clique of poets whose work The Dial has been interested in advancing, nor am I one of the smaller echoes of those poets which The Dial has published now and then. I should like to believe, however, that you are not in sympathy with this situation. I should like also to have a chat with you if your own desire is responsive.

I am enclosing two sonnets.

Quite sincerely yours,

Maxwell Bodenhiem

January 21, 1924

Dear Mr Bodenhiem:

When I said that it was painful to return a poem of yours I was speaking for myself and not for the other editors. I must confess, however, that I was not wholly aware of just how very painful such a refusal really was. Since receiving your last letter I have spent a most interesting hour going through your correspondence with The Dial for the past year or so. I am sorry indeed to appear to continue this tradition of what seems to you injustice, but nevertheless at the risk of incurring your displeasure for a second time, I am returning your two sonnets.

I should be most happy to meet you at any time.

Very sincerely yours,

Alyse Gregory

Managing Editor

January 24th

Dear Alyse Gregory:

Since you recently spent an interesting hour going through my correspondence with The Dial for the past two years, you may have noticed the droll ingenuity with which the editors of The Dial offered every known variety of excuse, sidestepping, polished retreat, unmeant praise, and slightly haughty restraint, to avoid any utterance of their actual preference and motives. I do not know whether their letters to me are included in your files, but my own carefully cherished collection of them will make an interesting addition to my memoirs, if I live long enough to write them. Yet, I have never charged the editors with injustice, but rather with a combination of comparative blindness, obeisance to one squad of poets only, and an invincible hypocrisy. If I am wrong, time will arrange my burial.

The poem in blank verse that I am enclosing is, to my hopelessly mesmerized eyes, beautiful and adroitly original, but, naturally, I do not expect The Dial to accept it. A second novel of mine, Crazy Man, will be issued by Harcourt Brace and Company during the coming week, and I hope that you will care to read it.

With great sincerity,

Maxwell Bodenhiem

January 25th 1924

Dear Alyse Gregory:

My publishers, Harcourt Brace and company, are mailing you a review copy of my latest novel, Crazy Man. I am hoping that you will care to review the novel yourself, simply because I have a presentiment that you would review it more fairly and seriously than the other people to whom The Dial has assigned my previous books. I need not say that I am not stooping to clumsy flattery in telling you this. I hope also, that The Dial will depart from its traditional policy toward my volumes and give the present one an early notice. Novels, alas, are materially made or discountenanced on the basis of the exact degree of immediate attention which they receive.

With great sincerity,

Maxwell Bodenheim

February 4 1924

My dear Mr Bodenheim:

Since you seem so certain that this poem will be returned, then here it is. You allude to the “polished retreats” of The Dial. One is apt to retreat when a howling dervish with glittering eye and bared teeth advances hostilely toward one. That one can remain polished under such circumstances is proof enough of one's “sangfroid.” One only advances for combat when one really enjoys the game and one does not enjoy a game when it is one's bones which are in danger rather than one's logic.

I have considered reviewing your book myself, but I am too busy to do any writing at the present time, so I have sent it to someone who is sure to give it sensitive and sympathetic consideration.

Very sincerely yours,

Alyse Gregory

February 5th

My dear miss Gregory:

Alas, our correspondence seems to be proceeding along the same roads taken by that between myself and other editors of The Dial. First the expression of an admiration, disputed by the endless return of my work; then a gradual yielding to the irritation at my insistent requests or delicate, explicit, considerate frankness; then a reaction of general dismay at my “disagreeable hostility”; and finally an indifference, or an angry retirement (we have not reached this last stage yet and I hope that we never will).

You say: “one is apt to retreat when a howling dervish with glittering eye and bird teeth advances hostility toward one”. Am I really as loud and whirling as all that? Or do I merely ask (with little confidence) for a direct confession of reasons and opinions, and for the removal of those nice garments which humans hug so desperately? For instance, let us take your sentence: “since you seem so certain that this poem will be returned, then here it is”. In the case of a magazine that rejects everything that I send in might I not be excused for being almost certain of the return of any particular poem?

And should this unfortunate certainty on my part be the only reason mentioned by the editor in explanation of the failure to accept the poem? Yes, these questions are futile, but they have not been caused by a mere pugnacious attitude. I came into this somewhat over polished and secretive world of yours with hopeless desire for open and detailed expressions, and when they are freely and accurately given to me I am content, regardless of whether the person appreciates my heart and mind. I am enclosing a poem which I am almost certain that The Dial will not take. If it should be returned, I hope that you will care to [tell] me this time exactly why it was dismissed... Some day I shall drop in as your office, when I can summon enough courage to do this.

With all sincerity,

Maxwell Bodenheim

February 20 1924

My dear Mr Bodenheim:

One must either send you a long analytical article as to one's reasons for returning your poems, or be termed evasive and hypocritical. It is hardly necessary for me to say that unique among poets and authors you ask such a thing of an editor.

Of course one returns your poems without explanation because no explanation could satisfy you.

It may interest you to know that we are expecting to have an article about your work published sometime in the near future.

Very sincerely yours,

Alyse Gregory

February 25th 1924

My dear Mr Bodenheim:

It is different in the case of a poet who has his own audience and his own particular niche in modern literature, for any editor to assign specific reasons for a particular rejection. Such reasons must of necessity be negative rather than positive. One of these might be, for instance, the absence from this poem of that direct emotional or magical thrill which Milton alluded to when he said that poetry should be simple, sensuous, and passionate. This poem has intellectual weight and moral indignation. My quarrel is that it becomes written rather from the rational surface of a vigorous mind than from those deeper levels of the imagination which evoke an immediate and unequivocal response. The energetic march of your reserved and calculated metre carries the mind along with it as far as it goes, but the final impression made by the poem seems to evaporate without creating any new or original vistas of human feeling. I hope this is a definite enough explanation to make you feel that my attitude is neither evasive nor hypocritical.

You may be interested to know that we are expecting to publish before very long an article about your work. But I believe I have mentioned this in a former letter.

Very sincerely yours,

Alyse Gregory

March 8th

My dear miss Gregory:

Thank you. In your last letter, for the first time in three and a half years, an editor of The Dial deserted the routine of courteous, factory-made fibs and high-perched irritation, and gave me a detailed direct and human statement of motives and opinions. I had prayed with a childlike and grotesque insistence for such a miracle, and the fact that it has come almost restores my faith in God and the benevolence of statesman.

The absence of “that direct emotional or magical thrill” and that “simple, sensuous, and passionate” quality, which you mention, does not always in my opinion, mutilate the animated body of a poem. Intellect is, after all just an earthly as emotional spontaneity, and a mound of frozen earth may be just as impressive as a warmer, plant-covered hill, and you will prefer either one according to the intensity with which you value your defeated second of life. To me, life is a foul, muddled, self-lacerating, squirming, mawkishly masked, coarse, vapidly tinkling saturnalia of illusions. There is a cold fire as well as a sensuous blaze, and I am wedded to the former... I am enclosing such a fire, and will you please let me hear from you very soon?

With much sincerity,

Maxwell Bodenheim

March 18 1924

My dear Mr Bodenheim:

This one we nearly did accept. Thank you for your most appreciative letter and I hope you will pardon me if I do not analyze our exact reasons for not publishing this present poem.

Very sincerely yours,

Alyse Gregory

April 3rd

My dear miss Gregory:

In your last letter of March the 18th you wrote, in regard to the rejection of a poem: “this one we nearly did accept”. I am filled with innocent wonder as to the exact boundary line between “accepting” and “nearly accepting”. Is the poem weighed upon hairs-breadth scales and found to lack an atom of weight, or is the process a broader one. In my own case, the phrase “nearly accepted”, from a magazine that practically never takes my verse, was mournfully intriguing and not quite expected. How on earth did my poetry manage to get as near as nearly in the active liking of The Dial? The poem in question, “Lynched Negro”, is better than half of the verse in all the issues of The Dial, and, in fact, its merits will probably cause other magazines to return it. I am enclosing another poem, and please let me hear from you soon. Quite sincerely yours,

Maxwell Bodenheim

April 15 1924

My dear Mr Bodenheim:

We are sorry to return this last poem of yours.

Very sincerely yours,

Alyse Gregory

July 14th

Dear miss Gregory:

Every now and then I am possessed by an impulse to send something to The Dial. I suppose it is like dispatching an emissary to the enemy, with a platter that bears fresh fruits and shows that you are still vigorously alive. Of course, there will be no need for your answering this letter unless The Dial accepts the enclosed poem, or unless you are seized by a whim to tell me the definite actual reason for the poem’s rejection. Our correspondence at the beginning of the year petered out so gradually and naturally, down to your final, twoiline note of conventional regret, that you may be reluctant to resume it.... You told me, months ago, that The Dial has received reviews of my last two books, Crazy Man and Against This Age, and intended to print them, but I have waited in vain for their appearance. When The Dial has finished dealing with its favorites, and with easier targets, it may then decide to publish the aforeentioned reviews.

Most sincerely

Maxwell Bodenheim

July 17 1924

My dear Mr Bodenheim:

Your urbane letter might almost tempt me to suppress entirely our review of your work. Unfortunately it is by one of our “favorites” therefore we hesitate and only slip it back in its envelope for a few more months. The real reason for not having published it sooner is that it is so much longer than our usual review that we have not been able to fit it in.

Very sincerely yours,

Alex Gregory

July 20th

My dear miss Gregory:

In your last communication you refer to the “urbane letter” which I wrote to you. If my letter was half as urbane as some of those in my prized collection of messages from The Dial editors, it must have been very smooth indeed. You tell me that the real problem for your not having published a review of my work is that the review was so much longer than your customary ones that you were unable to fit it in. In this connection, I remember a review of Ezra Pound's last book of verse which I wrote for The Dial some two or three years ago. My review is very long - 5 or 6 magazine pages in fact - but somehow The Dial managed to fit it into the very next issue, so that it would coincide with the publication of the book and be of maximum assistance to Mr Pound. Of course, there can be no valid objection to a magazine playing favorites, if it wants to, but it would be refreshing if the magazine openly admitted it and told each unlucky author: “you are not among those whose work is valued most highly, therefore you need not expect us to give you a work the same attentive and considerate if treatment which we accord to other writers”. Honestly, wouldn't that be a much better attitude to take?.

I am enclosing another excellent poem, just out of habit.

Most sincerely yours,

Maxwell Bodenheim

Writer, Novelist, and Critic

July 23rd 1924

My dear Mr Bodenheim:

You shouldn't make rejections so agreeable for one to write if you don't want to receive your things back again.

Too long a reiteration of grievances becomes at last a familiar drone that one finally disregards.

Very sincerely yours

Alyse Gregory

Managing editor

July 28th

My dear miss Gregory:

In regard to my last letter to you, you write: “too long a reiteration of grievances becomes at last a familiar drone that one finally disregards”.

The long reiteration of hedgings, apologies, sorrows, sidesteppings, and at times downright falsehoods, which I have received from The Dial editors during the past three and a half years, has been an equally familiar drone to my own sense of hearing. You also write: “you shouldn't make rejections so agreeable for me to write if you don't want to receive your things back again”. In your very first letter to me you expressed the deepest of sorrows at being forced to return my work, and if I have at least turned that sorrow into pleasure, you should be grateful to me. In persistently rejecting the best of my work for the past three years, The Dial has deprived itself of some excellent verse and prose and has played its part in depriving me of the material comfort and peace so invaluable to a creator. Perhaps The Dial’s loss has been greater than mine, and, at any rate, The Dial’s motives and tactics will be alertly judged by future eyes and ears.

In conclusion I must compliment you on being the first Dial editor who has ever given me a direct, ill-tempered affront. Since you were determined not to be quietly, good naturedly, and specifically frank -- which was all that I asked for — your sarcasm was at least more invigorating than your previous masks. Possibly, if The Dial changes managing editors at some future date, I may have an impulse to try the old experiment on your successor, but you need not fear that you will ever hear from me again.

Very truly yours

Maxwell Bodenheim

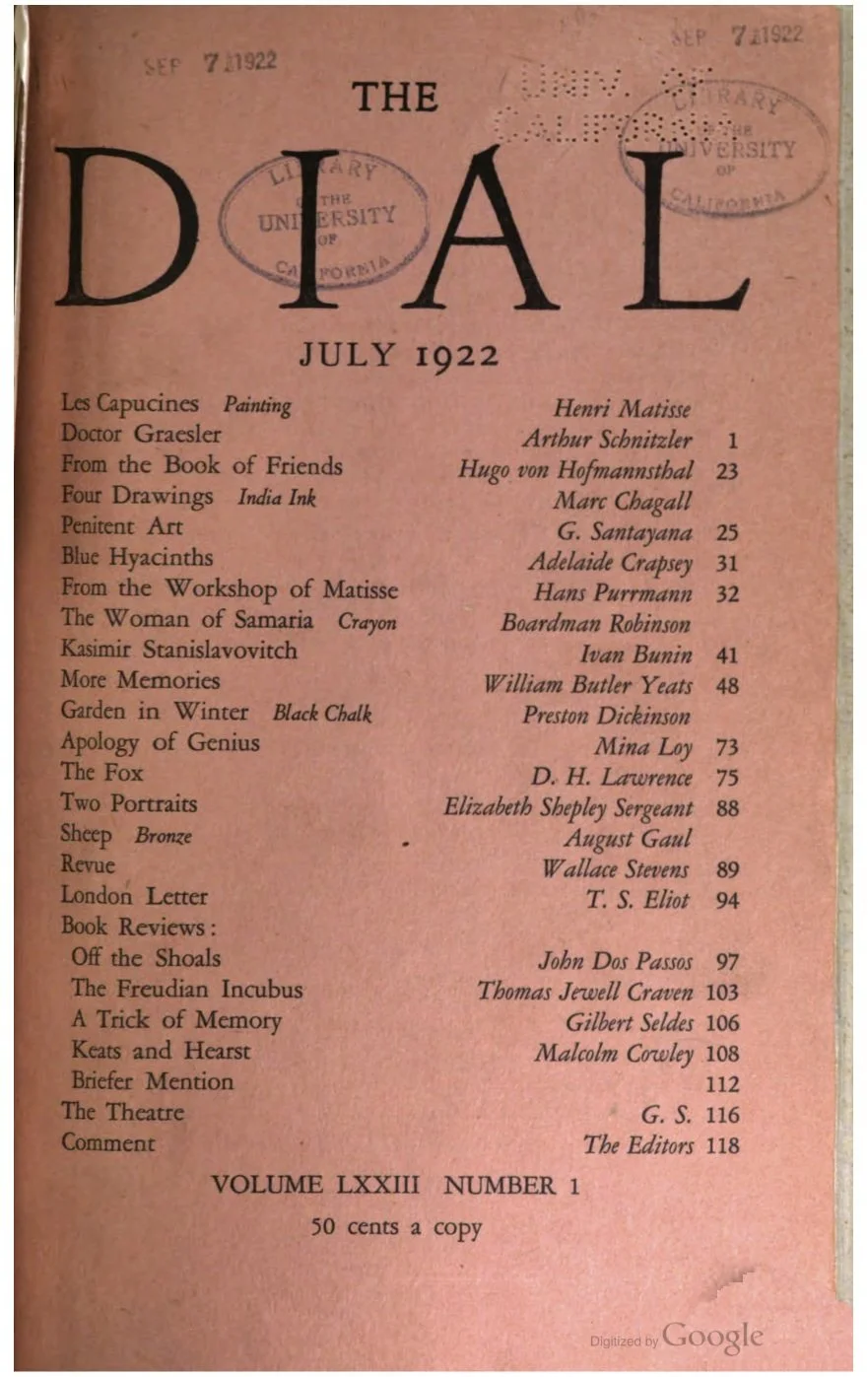

James Dempsey: With N.E. roots, The Dial became a Modernist monument

The first edition of the Modernist version of The Dial

SEE VIDEO AT BOTTOM

WORCESTER

When Scofield Thayer (picture at bottom) and James Sibley Watson put out their first issue of a radically restructured Dial magazine, at the beginning of 1920, the literati were unimpressed and indeed acidly disdainful. Ezra Pound called it “one of those mortuaries for the entombment of dead fecal mentality.” “It is very dull,” said T.S. Eliot, “just an imitation of The Atlantic Monthly with a few atrocious drawings reproduced.”

Those drawings were by poet and painter E.E. Cummings, who came in for more than his fair share of bashing. Robert Hillyer mocked his sketches of “trollops with their limbs spread wide apart” as well as the seven “awful” Cummings poems in the same issue, which included the now much-anthologized “Buffalo Bill’’.

“A pink thread of juvenility runs through it,” sniffed poet Conrad Aiken.

Be that as it may, writers were soon falling over each other in an undignified rush to get their work into the pages of this little magazine. All the above-mentioned critics appeared in The Dial in its first year and frequently thereafter, and the magazine went on to become arguably the most important of the magazines to promote and discuss those creative works that would come to be referred to, for better or worse, as “Modernist.”

The Dial published the works of writers and visual artists from 33 countries, many for the first time. Its scoops included T.S. Eliot's “The Waste Land’’ and "The Hollow Men"; E.E. Cummings's "in Just-"; W.B. Yeats's "The Second Coming"; Marianne Moore's "An Octopus"; Ezra Pound's “Hugh Selwyn Mauberley”; William Carlos Williams's "Paterson"; the first English translation of Thomas Mann’s Death in Venice; Virginia Woolf’s “Mrs. Dalloway in Bond Street,” and many others. The magazine also showcased such visual artists as Pablo Picasso, Marc Chagall, Gustav Klimt, Georgia O'Keeffe, Gaston Lachaise and Egon Schiele, often bringing their work before a wide public for the first time. Its regular correspondents included such luminaries of the period as Eliot, Pound, Thomas Mann and Maxim Gorki. Criticism was provided by Edmund Wilson, Van Wyck Brooks and Gilbert Seldes. Philosophers Bertrand Russell and George Santayana were frequent contributors.

Scofield Thayer

Those who appeared on the contents page — always listed on the cover -- included 11 Nobel and 24 Pulitzer prize-winners, as well as five U.S. Poet Laureates. And the journal’s particular emphasis on modern visual art was important in creating New York’s Museum of Modern Art. Thayer, Watson and their editors, including Gilbert Seldes, Alyse Gregory and Marianne Moore, were undoubtedly judicious and far-sighted in their tastes. From this age of great magazines, Malcolm Cowley singled out The Dial under Thayer as “the best magazine of the arts that we have had in this country.”

Thayer and Watson knew exactly what kind of magazine they wanted. They kept the book-review section from the old Dial, but they dumped the politics and added art, fiction, essays and much more poetry. The goals were lofty: Thayer wanted to print what he felt was ahead of, and even outside of, its time, material that “would otherwise have to wait years for publication,” as well as work struggling to find an audience and that “would not be acceptable elsewhere.” But he was also astute enough to realize that the audience for such, though enthusiastic, was small. Further, he saw no reason to exclude from the magazine established authors who were still producing important work. W.B. Yeats and Joseph Conrad were not yet “wholly dead,” he drolly pointed out.

Throughout its almost 10 years of existence, the avant-garde persistently criticized the magazine for being too staid, and old-school aesthetes denounced it for being too modern. This careful balancing of material, though, was in fact one of the aims of The Dial -- to promote and validate the work of younger writers and artists by their proximity to those who had more secure reputations. This leveling carried over into the fees paid by the magazine: Rates for all contributors, famous or not, were the same.

By its editors cannily blending the avant-garde with excellent but more established forms of visual art and literature, The Dial was transformed from a ploddingly progressive publication into a must-read for writers and artists of all stripes.

Thayer and Watson’s Dial was based in New York, but its New England pedigree was thorough. Ralph Waldo Emerson, the Concord essayist, philosopher and poet, launched the journal in 1840 as an outlet for Transcendentalist writing. Emerson, of Concord, Mass., hired the brilliant Margaret Fuller of Cambridge to help edit the magazine at $200 a year, a salary she never received. Amos Bronson Alcott called it “a free journal for the soul.’’

By the time that Emerson ended the magazine, in 1844, it had published Emerson, Fuller, John Sullivan Dwight, George Ripley, Samuel Gray Ward, William Ellery Channing, Frederic Henry Hedge, James Russell Lowell and Henry David Thoreau. In 1860, minister, abolitionist and Harvard graduate Moncure Daniel Conway launched a new version in Cincinnati. Conway managed to win Emerson’s blessing for the enterprise but was never able to persuade him to write for the magazine. It ceased publication after a year. Francis Fisher Browne, who was born in South Halifax, Vt., had more success with his Chicago Dial, which he started in 1880. It was slowly transformed from a somewhat conservative and apolitical journal into a Midwestern redoubt of culture and progressive politics. Browne had no college education. After high school, in 1862 he enlisted in the Forty-sixth Massachusetts Volunteers, which fought at the battles of Kinston, Whitehall and Goldsboro.

Apart from Watson, who was from Rochester, N.Y., all the above-named principals of the magazine, from Emerson on, were born in New England. (Thayer was a native of Worcester.) Most, including Watson, attended Harvard. Fuller, who in her time was considered the best-read person in New England, was the first woman allowed to use the library at Harvard College.

Little magazines have usually faced many threats to their existence, one of the main ones being lack of capital. For The Dial, this was never a problem. Thayer and Watson didn’t expect to make a profit or even to break even, and they constantly raided their personal fortunes to shovel money into the enterprise. Some years it cost them as much as $100,000, a not-so-small sum at the time. (By contrast, the first issue of William Carlos Williams’s Contact was run off on a donated mimeograph machine.) The principals of The Dial were by no means profligate with money—Thayer was notorious for quibbling about bills with tradesmen and others—but they both saw the journal as essentially coming under an umbrella of patronage. He bought the works of young artists, sent money to penurious writers -- James Joyce received $700 -- and established the annual Dial Award, a $2,000 gift for “service to letters”. And on some matters, expenses were never spared. When W.B. Yeats asked if he might change a line in “Leda and the Swan” after the issue had been sent to the printer’s, Thayer ordered the magazine containing the poem to be pulped and reprinted.

Nor did Thayer’s largesse stop there. E. E. Cummings was an ongoing charitable project, receiving $1,000 from Thayer to write a single poem, in addition to being paid for frequent contributions to the magazine, and even being given money to squire Thayer’s wife, Elaine, around New York City. (Soon after his marriage, Thayer became an acolyte of the Free Love movement and happily shared his wife, who had a child by Cummings, but that’s story for another time.)

Censorship was another threat. During the politically fraught times during and after The Great War and the Russian Revolution, the owners, editors, staff writers and contributors at little magazines, which tended to be politically and artistically radical, constantly ran the risk of being charged with everything from sedition to obscenity. In 1917, for example, staff members of The Masses were charged with violating the Espionage Act. They were eventually acquitted after two trials, but the magazine ceased publication. The editors of The Little Review famously were taken to court in 1922 and found guilty for publishing the allegedly obscene “Nausicaa” chapter of James Joyce’s Ulysses, a decision that essentially banned the book in the United States.

The Dial navigated these tricky shoals of censorship by knowing just how far the envelope could be pushed without putting the magazine’s future at risk. The nervous business manager, Lincoln MacVeagh, constantly begged Thayer not to publish risqué art, which weakened sales on newsstands. When book publisher Henry Holt saw in The Dial a photograph of Gleb Derujinsky’s sculpture of Leda being ravished by a cygnified Zeus, he gasped “Why, it’s coitus” and promptly canceled his advertising in The Dial. And when John R. Sumner, head of The New York Society for the Suppression of Vice, took umbrage at an article in the magazine attacking censorship, he was invited to submit a rebuttal. This he did in July 1921, and his piece made a very poor case, attacking “people in this country who like to bring forward something ‘foreign’ and hold it forth as an example of the way things should be done over here.’” The editors of that issue also made their own arch point by bookending Sumner’s piece with a George Moore sonnet in French and a Gaston Lachaise drawing of a naked and very buxom woman. At times, though, Thayer chose discretion over bravery; he vetoed reproduction of a painting by Georgia O’Keeffe as “commercially suicidal.” In some editorial decisions there was a cocking of the snoot at the authorities and in others the desire to ensure the future of the magazine. Thayer walked the line perfectly.

Thayer and Watson, both “Harvard men” from wealthy families, often clashed in their tastes. Thayer grew to abhor the productions of Ezra Pound and William Carlos Williams, while Watson was a great champion of both. Thayer was strongly inclined toward the visual art and literature of Germany and Austria, while Watson was a thoroughgoing Francophile. Thayer’s dislike of his former friend T.S. Eliot’s “The Waste Land” almost cost The Dial the first American publication of what would become the poem of the century, and it took all the diplomacy of Watson and the promise of the $2,000 Dial Award and other considerations to entice Eliot back on board. Other disagreements were often settled by veto, each man being allowed a single unchallenged rejection per issue. On a couple of occasions, Thayer threatened to step down from the magazine, but the two hung in together for six years before the 1926 mental breakdown that caused Thayer to leave the magazine and withdraw from public life. The Dial continued to publish until 1929, thus roughly bookending that miraculous decade of Modernism.

Thayer retired from the magazine and largely from public life in 1926. He had always been eccentric and suspicious of the people around him, but his mental condition deteriorated sharply in the mid-1920s, filling him with paranoia and a dread of being alone. He was eventually institutionalized and declared “an insane person”. For the rest of his long life (he died in 1982 at 92) he traveled among his homes with a nurse and servants.

Thayer had aspirations to be a poet, and constantly grumbled that his work on The Dial was preventing him from writing. But a century after he and Watson entered publishing, it is the magazine for which he is, and will always be, remembered.

James Dempsey, the author of The Tortured Life of Scofield Thayer, is an essayist, novelist and a writing teacher at Worcester Polytechnic Institute.