Don't worry yet about 'murder hornets' in N.E., at least not yet

Asian giant hornet

— Photo from Washington State Department of Agriculture

From ecoRi News (ecori.org)

News of the arrival in North America of a non-native insect with the terrifying colloquial name of “murder hornet” has alarmed residents nationwide. But a University of Rhode Island entomologist said there is little reason for Rhode Islanders {and thus by implication New Englanders in general} to worry about them.

Two murder hornets, which are more appropriately called Asian giant hornets, were discovered in Washington State in December shortly after a nest was discovered in nearby British Columbia. Native to Japan, where they are responsible for about 50 human deaths annually, the 2-inch-long insects with orange heads and black eyes are best known for their foraging behavior of ripping the heads off honeybees and feeding the rest of the bees’ bodies to their young.

“Their reputation as murder hornets comes from the fact that they can kill a lot of honeybees in a very short period of time,” URI entomologist Lisa Tewksbury said. “The major concern about their arrival in North America is for the damage they could cause to commercial honeybees used for pollinating agricultural fields. They are capable of quickly destroying beehives.”

Tewksbury said the hornet’s sting isn’t any more toxic than that of the bees and hornets commonly found in New England, but because of their large size, Asian giant hornets can deliver a larger dose of toxin with each sting. They are a danger to humans only when stung multiple times, according to Tewksbury.

“But they’re not known to aggressively attack humans,” she said. “It only happens occasionally and randomly.”

Rhode Island is home to two hornets similar in size to the Asian giant hornet: the cicada killer wasps, which dig their nests in sandy or light soil in areas such as athletic fields and playgrounds, and the European hornet, a non-native species that has become naturalized in New England after its arrival here in the 1800s. Like the Asian giant hornet, they are among the largest wasp-like insects in the world.

Tewksbury said that it’s extremely unlikely that the Asian giant hornets in the Pacific Northwest are in Rhode Island or likely will be soon. The concern is that no one knows how the hornets made it to Washington.

“We don’t know the pathway it took to get to Washington, and since we don’t know, it’s difficult to know how to prevent further introductions into North America,” she said.

Although she noted that Rhode Islanders need not be concerned about murder hornets, she advises residents to keep their eyes out for any unusual insect they’ve never seen before, since non-native insects do occasionally arrive in the region.

If you spot an unusual insect, Tewksbury said, take a picture of it and report it to the Rhode Island Department of Environmental Management’s invasive species sighting form.

Anders Corr/Kyoko Sato: Dreamy scapes of oil paint

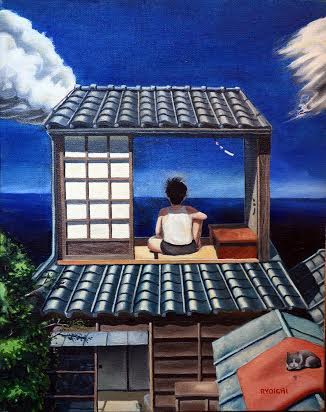

“Summer Winds” (oil on canvas, 1984), by RYOICHI MIURA. Courtesy of Kamakura Shirts Collection, Kanagawa, Japan.

“Summer Winds” (oil on canvas, 1984), by RYOICHI MIURA. Courtesy of Kamakura Shirts Collection, Kanagawa, Japan.

A boy sits on a miniscule tatami (a mat) on the second floor of a miniature house, gazing at the Pacific Ocean. A kitten sleeps on a pillow. Sounds of waves and wind chimes wash over a bicycle and tobacco box obscured by shadow on the ground floor. It’s a summer day in Japan.

The self-taught painter Ryoichi Miura (b. Japan 1956-) dreamed, in black and white, the scene painted in “Summer Winds”. He met us last week at the Harvard Club of New York City and over a summertime special of chilled avocado soup recounted his inspiration for the painting. “I wanted to color the scene. It was so unique to me because I had never seen a monochrome dream”. He just closed the show “Summer: Gallery and Invited Artists” (July 28-Aug. 15) at the Prince Street Gallery in New York.

A dreamy, deformé style epitomizes Ryoichi’s paintings. His signature and contemporary aesthetic is rooted in Garo, a monthly manga (comics) magazine (Seirindo, Japan, 1964-2002). “A big brother of my friend showed me the issue of July 1968 when I visited their home. I saw Ernest Hemingway’s The Killers, a comic {book} by Maki Sasaki. I was totally shocked and I could not move at all!”

Miura immediately asked his mother to subscribe to the magazine. When the bookstore hand-delivered his first issue, as was the norm in the 1960s, Miura jumped from the bathtub and ran dripping, merely covered by a towel, to receive it from the delivery man.

Ryoichi became an artist from that point. He drew his first manga, and brought it to school. His teacher read it aloud in the classroom. He still feels pride that everyone in the classroom, including his teacher, admired the art. Miura painted his first oil painting when he was 13, and has painted ever since. One of his earliest paintings still hangs in the principal’s room of his junior high school, Miura proudly recounts, 46 years later. Miura is now 59.

The earliest influence from manga is delightfully visible in his current art. Illustrations in his children’s book, Kids in N.Y. (Kaiseisha, Japan, 2003), are eerily angled, imbalanced, falling. “New York City is always moving. I wanted to express its movement and speed of the city.”

Miura is the Edward Hopper (American, 1882-1967) of his moment in New York City. Like Hopper, Miura’s paintings are lonely, urban, stark, transitory, estranged, anxious and tightly cropped. Yet Miura is hotter, faster, and more emotional.

Miura, above all, wants to communicate emotion. “I see a scene that gives me an emotional response,” he said. “I want the viewers of my paintings to feel this moment of emotion, the color, the movement.” His medium is important to his message. “I can express it [emotion, color, and movement] only because I am using oil, not camera.” Only with oil and the texture of paint, for example, does he believe that he could paint the smile of a woman, what became his favorite painting, in vermillion red. He says he will never be able to paint such a piece again, and has refused to sell it to buyers.

Ms. Tamiko Sadasue purchased “Summer Winds” in 2013 at the Prince Street Gallery because it symbolizes old Japan – a simpler time after World War II when she was a young girl and Japan had a dream. The painting hangs in Kanagawa Japan at the head office of her company, Kamakura Shirts, as a symbol of Japan’s dream of a prosperous future linked to a simpler, Hopperesque past.

While other artists chase new media, Miura sees value in the classical medium of oil. “I need to wait for 2 weeks for drying, always takes long, need to make tremendous efforts to finish a work. That is valuable for me, especially because we are living in such a convenient world,” says Miura. “I have many more objects and themes I want to paint. Through my paintings, I would like to show my own worlds with my own colors and textures to the people.“

Miura’s dream of painting color into the black and white, proceeds apace with the speed of New York City.

Anders Corr, Ph.D., founded Corr Analytics in 2013. Ms. Kyoko Sato is a curator in New York City.

Gregory N. Hicks: U.S. must stay at the trade table

The Boston Tea Party remains one of the seminal events in American history, and it continues to resonate among political elites, because most Americans believe that the “Tea Party” was a protest about taxation without representation.

It really wasn’t. It was actually about the setting of rules for international commerce without representation. John Hancock, a signer of the Declaration of Independence, merchant, ship owner and one of wealthiest men in the colonies, along with the Sons of Liberty, instigated the Boston Tea Party because the British government had given the British East India Company a monopoly to transport tea to the colonies and sell it there, effectively excluding American merchants from competing in a trade in which they had been profitably engaged. From the very beginnings of our republic, Americans have demanded the opportunity to compete internationally on a level playing field.

Two thousand years ago, Roman Senator Marcus Tullius Cicero said “the sinews of power are money, money, and more money.” This observation is as true for the 21st Century as it was in the First Century BCE. National power comes from national prosperity.

Fifteen years into the 21st Century, it is clear that the international economy has entered a transition period similar to the change that occurred a century ago, when the United States emerged as the world’s leading economic power. When that occurred, the United States did not use its economic power to influence global events, instead adopting a foreign policy of isolationism and international disarmament.

“The business of America is business,” said President Coolidge, and America’s insistence on repayment of World War I debts contributed to economic instability in Europe. Isolationism led to the Smoot-Hawley Tariff, the Great Depression and World War II.

Fully cognizant of this history as well as the necessity of rebuilding the world’s economy after World War II, the U.S. government leveraged America’s overwhelming post-war economic superiority to establish the dollar as the dominant currency of international finance and trade and to found the multilateral institutions that are the girders of today’s rules-based international economic system. The relatively level playing field for international commerce that was created has led to 70 years of economic growth and prosperity that has lifted millions from poverty.

Economies rose from the ashes of World War II by adopting key aspects of the American economic model, but in 1990, the United States was still the world’s largest economy. Our nearest competitor, Japan, had a GDP only 40 percent the size of America’s; China’s GDP was less than one-sixth the size of ours.

Today, the United States is no longer the world’s largest economy; that status belongs to the European Union. Most economists project that China will soon overtake the United States as the world’s largest national economy, although some argue that milestone has already been passed. Meanwhile, India’s economy is not too far behind.

Despite the emergence of multiple global economic competitors, the United States remains the acknowledged leader and fulcrum of the international economy. Five major trends in the global economy – the internet impact on international commerce, the emergence of global value chains, the oil exploration technology revolution, the rebound in U.S. manufacturing, and the resilience of the dollar after the 2008 financial crisis – illustrate the centrality of the United States to both the international economy and international relations.

We’re all familiar with the Internet’s impact on our daily lives, and at work, we experience the internet’s effects on productivity, but on a larger scale, it is also transforming international trade opportunities. For instance, E-bay and Amazon are fostering an Internet-based international retail revolution. The first company makes it possible for any individual to engage in an international commercial transaction. Any American who offers a good on E-bay could find that it has been purchased by someone from Ghana or Fiji; and the reverse transaction is equally possible. For its part, Amazon, based on its global warehouse network and relationships with modern logistical companies, has built a virtual mall in which customers can buy almost anything and have it delivered to their doorstep within a few days.

Internet communication has also made cross-border vertical integration of production, or global value chains, possible. Pioneered by Nike and improved by Apple, the process is perhaps epitomized today by Gilead, a San Francisco-based pharmaceutical company that is saving thousands of lives by developing and lowering consumer drug prices through innovative production arrangements with pharmaceutical producers in a number of developing countries.

Global value chains are inducing a reconsideration of the statistical analysis of international trade, which is changing perspectives on international economic policy. Analysts are grasping the importance of trade in intermediate goods, i.e., components or partially finished goods that are moving across borders through vertically integrated production processes. For the United States, one-third of exports and three-fifths of imports are intra-firm trade in intermediate goods.

A recent International Monetary Fund study looked at the major economic powers from the standpoint of domestic value-added (DVA) and foreign value-added (FVA) in their national output. The study found that China’s economy is the most dependent on foreign value-added content of any of the major economies, while the United States is the least dependent. The study also suggested that if China let its currency, the Yuan, appreciate, it would both move up the value chain and reduce the dependence of its economy on foreign inputs. Perhaps tellingly, China’s leaders have been allowing the Yuan to appreciate steadily over the past decade.

“Fracking,” that uniquely American technological innovation, is also changing the international policy landscape, and if the U.S. resumes exporting oil and natural gas, could have an even greater impact. The current policies of Arab oil-producing states clearly reflect their unease with growing American energy independence, while Europe, through employing fracking to develop its own energy resources or importing American oil and gas, has the potential to reduce its energy dependence on Russia by substantial amounts.

The manufacturing sector provides the tools of national power, and a newly released Congressional Research Service study suggests that all the talk of the demise of U.S. manufacturing is premature. While China became the world’s top manufacturing country in 2010, the United States remains second by a wide margin. In addition, U.S. manufacturing output grew between 2005 and 2013 by 5 percent, despite the Great Recession. Much of this growth was powered by inward foreign direct investment, 39 percent of which has been landing in the manufacturing sector.

Despite setbacks to the dollar’s reputation arising from the international financial crisis, the dollar continues to symbolize American economic strength and prowess. The dollar’s central role in international finance and trade provides unique avenues for the United States to use economic power in lieu of military intervention or other forms of pressure to resolve international problems. Yet that unique role is under competitive pressure as China, the European Union, Japan, Russia, India and Brazil all seek to put their currencies on an equal footing with the dollar.

International economic policy offers the U.S. government a range of tools to advance U.S. foreign policy and commercial interests in an increasingly competitive, multipolar environment. Among those tools, preferential trade and investment agreements positively affect more aspects of economies than any other. Not only do trade agreements lock-in existing trading and investment patterns, they create new links by eliminating trade barriers through reducing taxes and writing new trade and investment rules that go beyond those found in the 1994 World Trade Organization agreement.

In national power, trade agreements not only generate economic growth, jobs, and tax revenue, but they also create economic interdependence among agreement parties. The voluntary acceptance of that interdependence is an unambiguous symbolic foreign-policy statement. In a multipolar world, such agreements are essential to economic competitiveness and peaceful coexistence.

Our competitors understand these characteristics very well, including the axiom, illustrated by the 1773 Tea Act that sparked the Boston Tea Party: “He who writes the rules, wins.” They are aggressively negotiating trade pacts around the world, changing the terms and rules of trade in their favor. Currently, the European Union, formed itself by a trade agreement, has 32 preferential trade agreements in place with 88 countries, and it is currently negotiating 12 agreements covering an additional 36 countries. India’s existing preferential trade network includes 26 countries via 14 agreements, and it is negotiating four new agreements covering 37 additional nations. Japan has implemented 14 agreements with 16 countries, and is negotiating three trade agreements covering 35 nations. China has 12 preferential trade pacts in force with 21 countries, and is negotiating three more agreements that would cover 14 additional states.

Completing both the Trans-Pacific Partnership (TPP) and the Transatlantic Trade and Investment Partnership (TTIP) negotiations would expand the U.S. preferential trade network consisting of 14 agreements covering 20 countries to an additional 33 nations. TPP and TTIP involve three of the world’s top four economies and cover a majority of the world’s existing trade.

Moreover, they seek to write new trade rules that facilitate the growth of 21st Century international trading patterns such as e-commerce, global value chains, and foreign investment, among others. As importantly, they revitalize longstanding strategic relationships with our Asian and European allies, an important signal to both China and Russia that the United States intends to remain a competitive actor in Asia and Europe. Conversely, failure to complete these agreements would be an act of unilateral economic-policy disarmament with long term consequences for U.S. economic growth and national power.

In a 21st Century world that is more multipolar, more complex, more integrated and more competitive than the United States has ever experienced in its history, U.S. competitors and strategic allies alike – Brazil, China, the European Union, Japan, India, and Russia – are seeking to amass economic power and to deploy it as a leading element of their foreign policies. In many cases, they seek strategic advantages through these efforts, often at the expense of U.S. interests.

International economic-policy tools such as trade negotiations provide an effective, peaceful means to compete with these challenges. If we do not participate in making the rules for international trade, others will write our companies out of the competition, many jobs will be lost and many more never created, and our national prosperity and national power will decline. If they were alive today, John Hancock and the Sons of Liberty would support the negotiation of TPP and TTIP. We should too.

Gregory N. Hicks is State Department Visiting Fellow at the Center for Strategic and International Studies, in Washington; an economist and a veteran U.S. diplomat. The views expressed in this article are those of the author and do not necessarily represent the views of the U.S. Department of State or the U.S. government. This piece stems from Mr. Hicks's remarks at the June 9 meeting of the Providence Committee on Foreign Relations (thepcfr.org)

Robert Whitcomb: Another trap in the energy cycles

A few years ago I co-wrote a book, with Wendy Williams, about a controversy centered on Nantucket Sound. The quasi-social comedy, called Cape Wind: Money, Celebrity, Energy, Class, Politics and the Battle for Our Energy Future, told of how, since 2001, a company led by entrepreneur James Gordon has struggled to put up a wind farm in the sound in the face of opposition from the Alliance to Protect Nantucket Sound — a long name for fossil-fuel billionaire Bill Koch, a member of the famous right-wing Republican family. An amusing movie, Cape Spin, directed by John Kirby and produced by Libby Handros, came out of this saga, too. Mr. Koch's houses include a summer mansion in Osterville, Mass., from which he doesn’t want to see wind turbines on his southern horizon on clear days.

Mr. Koch may now have won the battle, as very rich people usually do. Two big utilities, National Grid and Northeast Utilities, are trying to bail out of a politicized plan, which they never liked, forcing them to buy Cape Wind electricity. They cite the fact that the company missed the Dec. 31, 2014, deadline in contracts signed in 2012 to obtain financing and start construction. Cape Wind said it doesn’t “regard these terminations as valid” since, it asserts, the contracts let the utilities’ contracts be extended because of the alliance’s “unprecedented and relentless litigation.” Bill Koch has virtually unlimited funds to pay lawyers to litigate unto the Second Coming, aided by imaginative rhetoric supplied by his very smart and well paid pit-bull anti-Cape Wind spokeswoman, Audra Parker, even though the project has won all regulatory approvals.

It's no secret that it has gotten harder and harder to do big projects in the United States because of endless litigation and ever more layers of regulation. Thus our physical infrastructure --- electrical grid, transportation and so on -- continues to fall behind our friendly competitors, say in the European Union and Japan, and our not-so-friendly competitors, especially in China. Read my friend Philip K. Howard's latest book, The Rule of Nobody, on this.

With the death of Cape Wind, New Englanders would lose what could have helped diversify the region’s energy mix — and smooth out price and supply swings — with home-grown, renewable electricity. Cape Wind is far from a panacea for the region’s dependence on natural gas, oil and nuclear, but it would add a tad more security.

Some of Cape Wind’s foes will say that the natural gas from fracking will take care of everything. But New England lacks adequate natural-gas pipeline capacity, to no small extent because affluent people along the routes hold up their construction. And NIMBYs (not in my backyard) have also blocked efforts to bring in more Canadian hydro-electric power. So our electricity rates are soaring, even as many of those who complain about the rates also fight any attempt to put new energy infrastructure near them. As for nuclear, it seems too politically incorrect for it to be expanded again in New England.

Meanwhile, the drawbacks to fracking, including water pollution and earthquakes in fracked countryside, are becoming more obvious. And the gas reserves may well be exaggerated. I support fracking anyway, since it means less use of oil and coal and because much of the gas is nearby, in Pennsylvania. (New York, however, recently banned fracking.)

Get ready for brownouts and higher electricity bills. As for oil prices, they are low now, but I have seen many, many energy price cycles over the last 45 years of watching the sector. And they often come with little warning. But meanwhile, many Americans, with ever-worsening amnesia, flock to buy SUV's again.

Robert Whitcomb oversees New England Diary.

Blame Russia for Russian aggression

By ROBERT WHITCOMB (rwhitcomb51@gmail.com)

Some denounce the United States for Russia’s reversion to brutal expansionism into its “Near Abroad” because we encouraged certain Central and Eastern European countries to join the North Atlantic Treaty Organization. The argument is that NATO’s expansion led “Holy Russia” to fear that it was being “encircled.” (A brief look at a map of Eurasia would suggest the imprecision of that word.)

In other words, it’s all our fault. If we had just kept the aforementioned victims of past Russian and Soviet expansionism out of the Western Alliance, Russia wouldn’t have, for example, attacked Georgia and Ukraine. If only everyone had looked into Vladimir Putin’s eyes and decided to trust him.

Really? Russia has had authoritarian or totalitarian expansionist regimes for hundreds of years, with only a few years’ break. How could we have necessarily done anything to end this tradition for all time after the collapse of the Soviet iteration of Russian imperialism? And should we blame Russia’s closest European neighbors for trying to protect themselves from being menaced again by their gigantic and traditionally aggressive neighbor to the east? Russia, an oriental despotism, is the author of current Russian imperialism.

Some of the Blame America rhetoric in the U.S. in the Ukraine crisis can be attributed to U.S. narcissism: the idea that everything that happens in the world is because of us. But Earth is a big, messy place with nations and cultures whose actions stem from deep history and habits that have little or nothing to do with big, self-absorbed, inward-looking America and its 5 percent of the world population. Americans' ignorance about the rest of the planet -- even about Canada! -- is staggering, especially for a "developed nation''.

And we tend to think that “personal diplomacy” and American enthusiasm and friendliness can persuade foreign leaders to be nice. Thus Franklin Roosevelt thought that he could handle “Joe Stalin” and George W. Bush could be pals with another dictator (albeit much milder) Vladimir Putin. They would, our leaders thought, be brought around by our goodwill (real or feigned).

But as a friend used to say when friends told him to “have a nice day”: “I have other plans.”

With the fall of the Soviet Empire, there was wishful thinking that the Russian Empire (of which the Soviet Empire was a version with more globalist aims) would not reappear. But Russian xenophobia, autocracy, anger and aggressiveness never went away.

Other than occupying Russia, as we did Japan and Western Germany after World War II, there wasn’t much we could do to make Russia overcome its worst impulses. (And Germany, and even Japan, had far more experience with parliamentary democracy than Russia had.) The empire ruled from the Kremlin is too big, too old, too culturally reactionary and too insular to be changed quickly into a peaceable and permanent democracy. (Yes, America is insular, too, but in different ways.)

There’s also that old American “can-do” impatience — the idea that every problem is amenable to a quick solution. For some reason, I well remember that two days after Hurricane Andrew blew through Dade County, Fla., in 1992, complaints rose to a chorus that President George H.W. Bush had not yet cleaned up most of the mess. How American!

And of course, we’re all in the centers of our own universes. Consider public speaking, which terrifies many people. We can bring to it extreme self-consciousness. But as a TV colleague once reminded me, most of the people in the audience are not fixated on you the speaker but on their own thoughts, such as on what to have for dinner that night. “And the only thing they might remember about you is the color of the tie you’re wearing.”

We Americans could use a little more fatalism about other countries.

***

James V. Wyman, a retired executive editor of The Providence Journal, was, except for his relentless devotion to getting good stories into the newspaper, the opposite of the hard-bitten newspaper editor portrayed in movies, usually barking out orders to terrified young reporters. Rather he was a kindly, thoughtful and soft-spoken (except for a booming laugh) gentleman with a capacious work ethic and powerful memory.

He died Friday at 90, another loss for the "legacy news media.''

***

My friend and former colleague George Borts died last weekend. He was a model professor — intellectually rigorous, kindly and accessible. As an economist at Brown University for 63 years (!) and as managing editor of the American Economic Review, he brought memorable scholarship and an often entertaining skepticism to his work. And he was a droll expert on the law of unintended consequences.

George wasn’t a cosseted citizen of an ivory tower. He did a lot of consulting for businesses, especially using his huge knowledge of, among other things, transportation and regulatory economics, and wrote widely for a general audience through frequent op-ed pieces. He was the sort of (unpretentious) “public intellectual” that we could use a lot more of.

***

I just read Philip K. Howard’s “The Rule of Nobody: Saving America From Dead Laws and Broken Government.” I urge all citizens to read this mortifying, entertaining and prescriptive book about how our extreme legalism and bureaucracy imperil our future. I’ll write more about the book in this space.

Robert Whitcomb (rwhitcomb51@gmail.com), a former editor of The Providence Journal's editorial pages, is a Providence-based writer and editor, former finance editor of the International Herald Tribune and a partner and senior adviser at Cambridge Management Group (cmg625.com), a consultancy for health systems, and a fellow of the Pell Center for International Relations and Public Policy.

member of.