Llewellyn King: To revive America, fix the gig economy and bring back the WPA

McCoy Stadium, in Pawtucket, R.I., was a WPA project….

…and so was this field House and pump station in Scituate, Mass.

The assumption is that we’ll return to work when COVID-19 is contained, or we have adequate vaccines to deal with it.

That assumption is wrong. For many millions, maybe tens of millions, there will be no work to return to.

At root is a belief that the United States -- and much of the world -- will spring back as it did after the 2008 recession: battered but intact.

Fact is, we won’t. Many of today’s jobs won’t exist anymore. Many small businesses will simply, as the old phrase says, go to the wall. And large ones will be forced to downsize, abandoning marginal endeavors.

When we think of small businesses, we think of franchised shops or restaurants and manufacturers that sell through giants like Amazon and Walmart. But the shrinkage certainly goes further and deeper.

Retailing across the board is in trouble, from the big-box chains to the mom-and-pop clothing stores. The big retailers were reeling well before the coronavirus crisis. Neiman Marcus, an iconic luxury retailer, has filed for bankruptcy. All are hurt, some so much so – especially malls -- that they may be looking to a bleak future.

The supply chain will drive some companies out of business. Small manufacturers may find that their raw material suppliers are no longer there or that the supply chain has collapsed – for example, the clothing manufacturer who can’t get cloth from Italy, dye from Japan or fastenings from China. Over the years, supply chains have become notoriously tight as efficiency has become a business byword.

Some will adapt, some won’t be able to do so. A record 26.5 million Americans have sought unemployment benefits over the past five weeks. Official unemployment numbers have always been on the low side as there’s no way of counting those who’ve given up, those who work in the gray economy, and those who for other reasons, like fear of officialdom or lack of computer skills, haven’t applied for unemployment benefits.

To deal with this situation the government will have to be nimble and imaginative. The idea that the economy will bounce back in a classic V-shape is likely to prove illusory.

The natural response will be for more government handouts. But that won’t solve the systemic problem and will introduce a problem of its own: The dole will build up dependence.

I see two solutions, both of which will require political imagination and fortitude. First, boost the gig economy (contract and casual work) and provide gig workers with the basic structure that formal workers enjoy: Social Security, collective health insurance, unemployment insurance and workers’ compensation. The gig worker, whether cutting lawns, creating Web sites, or driving for a ride-sharing company, should be brought into the established employment fold; they’re employed but differently.

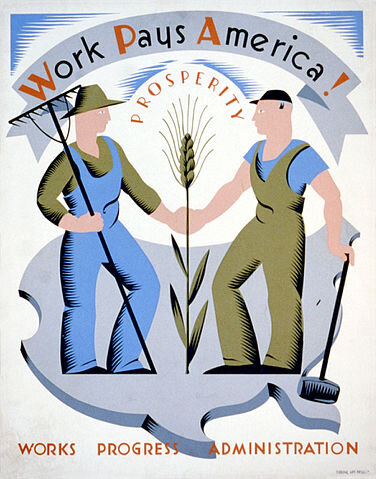

Second, a new Works Progress Administration (WPA) should be created using government and private funding and concentrating on the infrastructure. The WPA, created by President Franklin D. Roosevelt in 1935, ended up employing 8.5 million Americans, out of a total population of 127.3 million, in projects ranging from mural painting to bridge building. Its impact for good was enormous. It fed the hungry with dignity, not the soup kitchen and bread line, and gave America a gift that has kept on giving to this day.

Jarrod Hazelton, a Rhode Island-based economist who’s researched the WPA, says the agency gave us 280,000 miles of repaired roads, almost 30,000 new and repaired bridges, 600 new airports, thousands of new schools, innumerable arts programs, and 24 million planted trees. It also enabled workers to acquire skills and escape the dead-end jobs they’d lost. It was one of the most successful public-private programs in all of history.

As the sea levels rise and the climate deteriorates, we’ll need a WPA, tied in with the Army Corps of Engineers, to help the nation flourish in the decades of challenge ahead. The original was created by FDR with a simple executive order.

Llewellyn King is executive producer and host of White House Chronicle, on PBS. His e-mail address is llewellynking1@gmail.com and he’s based in Rhode Island and Washington, D.C.

Llewellyn King's Notebook: Tale of many weddings; obscene executive pay; Electronicsville

I have been to some amazing weddings. My own (three) have been quite modest, but I have been to some that were extraordinary bashes, with brides in designer gowns and grooms who looked as though they were dressed by Savile Row, and indeed some were.

I have been to Virginia Hunt Country weddings where you would think it was the horses who were getting married, and Irish weddings where you would think the celebrants would all need first responders' help in getting home.

I even can claim, sort of, a royal wedding. In 1960, I helped cover the marriage of Princess Margaret and Anthony Armstrong-Jones in Westminster Abbey. I got a few paragraphs in a major London newspaper and thought I had arrived. In reality, I was on a ferry on the Thames and nowhere near the actual wedding: My job was to report on the crowds waiting for the Royal Yacht to take the newlyweds on honeymoon. All that, it turns out was prelude to the main event.

Last month I went to the wedding of weddings, the nuptials extraordinaire in my book. It topped all the others not in grandeur, but in infectious joy. It was the joining together, as they say, of Hannah Tessitore and Jarrod Hazelton, and I was inside enjoying really good red wine and Beef Wellington, not outside on a boat on a cold London day. These were royals of a kind, more so, methinks.

It all happened in the Rhode Island Yacht Club, an auspicious place, jutting out into upper Narraganset Bay, almost surrounded by water and with resident swans, although I did not notice them being more or less celebratory than usual. Swans are tricky that way.

It was the meeting of a family, hers that's partly Italian and his a mixture of English and German, via South America. Hannah is one of the most gifted people I have worked with. She is a producer on my television show and a quite fabulous Web designer. Jarrod is an economist and polymath; one of those people who seems to know more about everything than you do. This coupled with sardonic wit makes him awesome in a nonthreatening way.

I love their love story. They did not meet on a blind date, nor through a computer site, nor were they neighbors. They met -- Cupid is an imaginative fellow -- in line at an ATM. And I thought that those things just dispensed money.

As Noel Coward said in a song, “I’ve been to a marvelous party.”

Executive Pay: How High the Moon?

When I leaned that an executive at Enron was making $80 million, I told the chairman, a friend, Ken Lay, “Ken, you can get very good help for just $20 million.”

This comes to mind when I read that a near friend (a lot of those in journalism, where you are friendly but in a circumscribed way) has just had his salary raised to $15 million. Nice work if you can get it, but the board should have said no. The unions should have pounced and the customers should turn away.

Excessive executive pay is one of the things that contributes to the sense that most of us are doomed wage-wise, while the precious few are elevated above reason to a place where their compensation distorts the national well-being.

Years ago, before the nation became so inured to the C-suite ripoffs, the conservative columnist George Will said the executive compensation of the heads of public companies had reached a point where these lucky few were “taking,” not earning, their huge wealth. Quite so. It is enough to make a chap sing “La Marseillaise” in the bath.

How We Live Now: Life in Electronicsville

I read a lot of books, though not as many as I would like. I read so damn slowly. My wife, Linda Gasparello, tears up the typographical turnpike at an impressive clip, while I stay close to the curb.

Using a Kindle, I do find I get through more books. It is a clunky devise that needs refinement, but it is so portable. I am reading more books because I always have the gadget with me -- on a bus, plane or train, at the barbershop, while waiting for a friend at a restaurant.

The trouble is you do not have a book afterward, and you have really only rented one. No book to hand on, to grace your shelves. Also, to my shame, I can count the jobs lost when a book comes electronically and not physically: the typesetter, the printer, the binder, the trucker, the warehouse worker and the sales clerk. It is shameful, it is the future and it is me, circa 2017.

Llewellyn King, a frequent contributor to New England Diary, is host and executive producer of White House Chronicle, on PBS.