Term limits look better and better in Connecticut

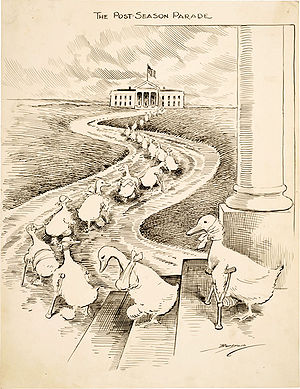

The lame ducks depicted in this Clifford K. Berryman cartoon are defeated Democrats heading to the White House hoping to secure political appointments from President Woodrow Wilson.

Columnist Jim Cameron in the Stamford Advocate has curtly written off Connecticut Gov. Dannel Malloy: “Our governor is a lame duck. Because he’s announced he’s not running for re-election, he has the political clout of a used teabag. And even though he’s our state’s leader for another 11 months, nobody cares about him or his ideas any longer.”

Malloy’s lieutenant governor, Nancy Wyman, has decided she would rather be spending time with her family than running for governor, which would necessarily entail a hearty defense of Malloy’s ruinous policies.

After two terms making Connecticut great again, Malloy himself has decided to take a hike.

Atty. Gen. George Jepsen, whose time in office was spent avoiding media notoriety -- unlike his predecessor, Dick Blumenthal, for whom fawning media attention was the River Styx in which he bathed frequently – has called it a day after two terms as Connecticut’s AG. And no, the former chairman of the State Democratic Party has no plans to run for governor. Both Blumenthal and former Atty. Gen. Joe Lieberman used the AG’s office as springboard to a U.S. Senate sinecure.

Mayor of Hartford Luke Bronin, once Malloy’s chief counsel, having said he would need a couple of terms in office to turn the U.S.S. Hartford around, has rushed into the vacuum created by Malloy’s departure. Connecticut’s capital is taking on water. Only a few weeks ago, Bronin was palavering with lawyers about a bankruptcy declaration, and if he now feels the governor’s office is a politically safe haven compared to the mayoralty of Hartford, he’s one bright cookie. Most lawyers are not dummies. despite the usual bad rap on the comic circuit. Question: What do you call a lawyer with an I. Q. of 50? Answer: Your honor.

An open Democrat gubernatorial field has yanked Ned Lamont from the shadows. Lamont, a cable millionaire and great-grandson of a late chairman of J.P. Morgan & Co. Thomas Lamont, successfully challenged then U.S. Sen. Joe Lieberman in a Democrat primary; he then lost to Lieberman, who successfully defended his seat as an independent in a general election. “Lamont spent $26 million of his cable television fortune on his run for the Senate and for governor,” Neil Vigdor of CTPostreminds us, and Lamont was, of course, supported by former U.S. Sen. Lowell Weicker, who is still recovering from his 1988 loss to Lieberman.

“I just care about whether I think I can make a difference and get this state back on track,” Lamont said. “We’ve got so many amazing assets. We’re just not making the best out of our potential.” Lamont indicated that he would decide by January whether he would throw his hat into the gubernatorial ring. By that time, the floor on both sides of the political barracks will be littered with hats.

These bow-outs of Malloy, Wyman and Jepsen have kicked the doors open on an election that promises to be alarmingly interesting. If anyone wants to know how term limits might introduce into Connecticut’s sclerotic political system the verve and energy of a new day, they have only to look about them. Had term limits been in force midway between Dick Blumenthal’s agonizingly long 20-year term as the state’s attorney general he might have been a U.S. senator or possibly governor more than 10 years earlier; for it is not true that term limits would end political careers. They would simply move the pieces on the political chessboard toward different political functions. PAC committees, easily captured by incumbents, would have to decide, upon a governor or a senator leaving his post, who they might want to corrupt in the future; in the absence of a healthy turn-over in various offices, corruption has become routine, predictable and automatic. Term limits would invigorate political parties, and awaken all the nerve tingling juices of reporters during election cycles.

This is precisely what is happening right now that three prominent officeholders have decided in effect to term limit themselves.

Jepsen’s political career has been well rounded: In 2018, he will have put in eight years as attorney general. But Jepsen also served in the State House for four years and the State Senate for 12 years. He served as chairman of the state Democratic Party for two years. These terms in different political offices approximate term limit spans. Jepsen circulated himself through a now sclerotic political system, and no one is complaining that the state Senate, for example, has been irreparably damaged because Jepsen did not spend as much time there as Blumenthal had in the attorney general’s office.

Had term limits been in operation for the last few election cycles, no one in the Democratic Party would be wincing at the prospect that a Bridgeport mayor who spent years in prison for corruption might become the next governor of Connecticut. The gubernatorial field on the Democratic side would now be crowded with recirculated Democrats, some of whom just might be able to pull Connecticut out of its progressive mire by its former moderate and pragmatic bootstraps.

Don Pesci is a Vernon, Conn.-based columnisf.