They want to know why you were out late

Work by New Hampshire-basedfartist Tim Campbell at the Hannah Grimes Art Center, Keene, N.H.

Barbara Gibbs wrote in the Laconia (N.H.) Daily Sun:

“Tim Campbell identifies with the term of outsider art, which was coined by an art critic in 1972 as an English synonym for ‘art brut’– French, meaning raw art or rough art. The critic, Roger Cardinal, used this term to describe art created outside the boundaries of official culture. The term outsider art is often applied more broadly to include self-taught or naïve art makers. Campbell's work reflects his sharp sense of humor, and interest in primitive folk art as well as contemporary political and religious imagery.’’

1907 postcard from when Keene was an important manufacturing town. Now it has mostly a service economy, including Keene State College and Antioch University New England.

Malaise of elderly grows as pandemic grinds on

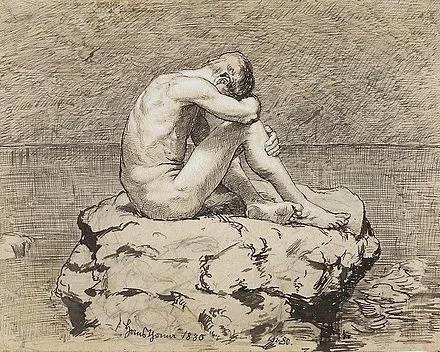

“Loneliness,’’ by Hans Thoma, in the National Museum in Warsaw.

“Folks are becoming more anxious and angry and stressed and agitated because this has gone on for so long.’’

— Katherine Cook, chief operating officer of Monadnock Family Services in Keene, N.H., which operates a community mental-health center that serves older adults.

Late one night in January, Jonathan Coffino, 78, turned to his wife as they sat in bed. “I don’t know how much longer I can do this,” he said, glumly.

Navigating Aging focuses on medical issues and advice associated with aging and end-of-life care, helping America’s 45 million seniors and their families navigate the health care system

Coffino was referring to the caution that’s come to define his life during the COVID-19 pandemic. After two years of mostly staying at home and avoiding people, his patience is frayed and his distress is growing.

“There’s a terrible fear that I’ll never get back my normal life,” Coffino told me, describing feelings he tries to keep at bay. “And there’s an awful sense of purposelessness.”

Despite recent signals that COVID’s grip on the country may be easing, many older adults are struggling with persistent malaise, heightened by the spread of the highly contagious omicron variant. Even those who adapted well initially are saying their fortitude is waning or wearing thin.

Like younger people, they’re beset by uncertainty about what the future may bring. But added to that is an especially painful feeling that opportunities that will never come again are being squandered, time is running out, and death is drawing ever nearer.

“I’ve never seen so many people who say they’re hopeless and have nothing to look forward to,” said Henry Kimmel, a clinical psychologist in Sherman Oaks, California, who focuses on older adults.

To be sure, older adults have cause for concern. Throughout the pandemic, they’ve been at much higher risk of becoming seriously ill and dying than other age groups. Even seniors who are fully vaccinated and boosted remain vulnerable: More than two-thirds of vaccinated people hospitalized from June through September with breakthrough infections were 65 or older.

The constant stress of wondering “Am I going to be OK?” and “What’s the future going to look like?” has been hard for Kathleen Tate, 74, a retired nurse in Mount Vernon, Wash. She has late-onset post-polio syndrome and severe osteoarthritis.

“I guess I had the expectation that once we were vaccinated the world would open up again,” said Tate, who lives alone. Although that happened for a while last summer, she largely stopped going out as first the delta and then the omicron variants swept through her area. Now, she said she feels “a quiet desperation.”

This isn’t something that Tate talks about with friends, though she’s hungry for human connection. “I see everybody dealing with extraordinary stresses in their lives, and I don’t want to add to that by complaining or asking to be comforted,” she said.

Tate described a feeling of “flatness” and “being worn out” that saps her motivation. “It’s almost too much effort to reach out to people and try to pull myself out of that place,” she said, admitting she’s watching too much TV and drinking too much alcohol. “It’s just like I want to mellow out and go numb, instead of bucking up and trying to pull myself together.”

Beth Spencer, 73, a recently retired social worker who lives in Ann Arbor, Mich., with her 90-year-old husband, is grappling with similar feelings during this typically challenging Midwestern winter. “The weather here is gray, the sky is gray, and my psyche is gray,” she told me. “I typically am an upbeat person, but I’m struggling to stay motivated.”

“I can’t sort out whether what I’m going through is due to retirement or caregiver stress or covid,” Spencer said, explaining that her husband was recently diagnosed with congestive heart failure. “I find myself asking ‘What’s the meaning of my life right now?’ and I don’t have an answer.”

Bonnie Olsen, a clinical psychologist at the University of Southern California’s Keck School of Medicine, works extensively with older adults. “At the beginning of the pandemic, many older adults hunkered down and used a lifetime of coping skills to get through this,” she said. “Now, as people face this current surge, it’s as if their well of emotional reserves is being depleted.”

Most at risk are older adults who are isolated and frail, who were vulnerable to depression and anxiety even before the pandemic, or who have suffered serious losses and acute grief. Watch for signs that they are withdrawing from social contact or shutting down emotionally, Olsen said. “When people start to avoid being in touch, then I become more worried,” she said.

Fred Axelrod, 66, of Los Angeles, who’s disabled by ankylosing spondylitis, a serious form of arthritis, lost three close friends during the pandemic: Two died of cancer and one of complications related to diabetes. “You can’t go out and replace friends like that at my age,” he told me.

Now, the only person Axelrod talks to on a regular basis is Kimmel, his therapist. “I don’t do anything. There’s nothing to do, nowhere to go,” he complained. “There’s a lot of times I feel I’m just letting the clock run out. You start thinking, ‘How much more time do I have left?’”

“Older adults are thinking about mortality more than ever and asking, ‘How will we ever get out of this nightmare,’” Kimmel said. “I tell them we all have to stay in the present moment and do our best to keep ourselves occupied and connect with other people.”

Loss has also been a defining feature of the pandemic for Bud Carraway, 79, of Midvale, Utah, whose wife, Virginia, died a year ago. She was a stroke survivor who had chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and atrial fibrillation, an abnormal heartbeat. The couple, who met in the Marines, had been married 55 years.

“I became depressed. Anxiety kept me awake at night. I couldn’t turn my mind off,” Carraway told me. Those feelings and a sense of being trapped throughout the pandemic “brought me pretty far down,” he said.

Help came from an eight-week grief support program offered online through the University of Utah. One of the assignments was to come up with a list of strategies for cultivating well-being, which Carraway keeps on his front door. Among the items listed: “Walk the mall. Eat with friends. Do some volunteer work. Join a bowling league. Go to a movie. Check out senior centers.”

“I’d circle them as I accomplished each one of them. I knew I had to get up and get out and live again,” Carraway said. “This program, it just made a world of difference.”

Kathie Supiano, an associate professor at the University of Utah College of Nursing who oversees the COVID grief groups, said older adults’ ability to bounce back from setbacks shouldn’t be discounted. “This isn’t their first rodeo. Many people remember polio and the AIDS epidemic. They’ve been through a lot and know how to put things in perspective.”

Alissa Ballot, 66, realized recently she can trust herself to find a way forward. After becoming extremely isolated early in the pandemic, Ballot moved last November from Chicago to New York City. There, she found a community of new friends online at Central Synagogue in Manhattan and her loneliness evaporated as she began attending events in person.

With Omicron’s rise in December, Ballot briefly became fearful that she’d end up alone again. But, this time, something clicked as she pondered some of her rabbi’s spiritual teachings.

“I felt paused on a precipice looking into the unknown and suddenly I thought, ‘So, we don’t know what’s going to happen next, stop worrying.’ And I relaxed. Now I’m like, this is a blip, and I’ll get through it.”

Judith Graham is a Kaiser Health News reporter.

'Loved most a blizzard'

“He loved winter more than the other seasons, loved a tender snowfall, loved the savage north wind and the blinding light off a frozen lake, loved most a blizzard, which he faced head-on like a bison. He would not admit these things, however, because in his superstition he believed that by revealing desires among sacred subjects, such as weather and seasons, you would likely receive the opposite of what you wanted.’’

-- Ernest Hebert (born 1941), in The Dogs of March (1979) . He is best known for the Darby Chronicles Series, a series of seven novels written between 1979 and 2014 about modern life in a fictional New Hampshire town as it changed from relative rural poverty to becoming more upscale, almost suburban. He was born in, and spent many years in and around, Keene, N.H. It’s a very pleasant small city in southwest New Hampshire.

Central Square, in Keene